18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

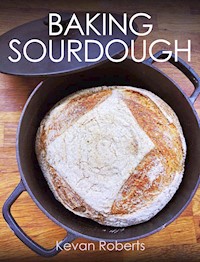

Baking is a truly multi-sensory experience; baking with sourdough takes this experience to the next level. Celebrated for its health benefits, superior texture and unique flavour, sourdough goes back to the roots of traditional bread making and gives you the freedom to craft your own dietary staple to your own specifications.Artisan baker, Kevan Roberts, takes readers on a sensory journey through the formation of sourdough from natural yeast to the craft of producing your own perfect loaf, before extending this knowledge to make croissants, pancakes, pizza and more. Step-by-step photographs, detailed guides and original recipes provide a thorough and inspiring understanding of the sourdough process. It includes the history and development of sourdough; how to build and maintain a healthy sourdough starter; essential equipment, methods, and preferments; techniques in kneading, shaping, scoring and baking; converting commercial yeasted products to sourdough; gluten-free sourdough and finally, a comprehensive troubleshooting guide. Thirty detailed recipes are given from a basic starter to international breads and creative bakes. Baking Sourdough enables all bread-lovers - from professionals looking for a means of bulk producing the same sour hit every time to at-home bakers taking their initial steps into baking with natural yeast - to create their own freshly baked sourdough, again and again.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

BAKINGSOURDOUGH

BAKINGSOURDOUGH

Kevan Roberts

First published in 2020 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© Kevan Roberts 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 684 5

AcknowledgementsI would like to extend special thanks to Crowood, for approaching me with the idea of a book that suits my passions down to the ground, and allowing me to share my knowledge with others.

The people at Wright’s Flour Mill were exceptionally helpful in providing me with insights into their industry, and opening my eyes to the story of the origins of bread. Since the spike in my interest in milling, Komo have provided me with a home grain mill, which has given me the opportunity to explore creating and developing my own flours. My explorations have provided me with vital research to pour into these pages.

I would like to thank Bread Ahead for giving me confidence in the teaching capabilities that have made this book possible. Thank you, also, to Helen Kilner, whose pottery expertise was invaluable in creating the fermentation jars.

Many thanks go to my wife Kathryn, without whose patience I would not have made it past my first draft. I would also like to thank my talented daughter Saffron, who helped me so much to pull this book together and make sense of my ramblings.

The last acknowledgement goes to my darling mum Gladys, who taught me never to give up on my dreams.

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 The History of Sourdough

2 Sourdough Starter

3 Fundamentals and Methods

4 Creative Sourdough

5 Sourdough: A Lifestyle Choice

6 Modifications

7 Worldwide Sourdoughs

8 Troubleshooting Guide and Top Tips

9 Conclusion

References

Conversion Charts

Recipe Index

Index

INTRODUCTION

This book will take you on a journey through the world of sourdough. It will follow the historical timeline of the development of this foodstuff through the ages, from its Neolithic birth to its near demise and consequent revival, as it played an integral part in the Artisan Movement. Despite a resurgence in the popularity of sourdough in recent years, it has not always been appreciated.

Baking Sourdough will show how sourdough is formed from natural yeast, and describe the intriguingly easy, and inexpensive, method that leads to such a highly developed sensory experience. It aims to bring to life the world of sourdough and enable all bread lovers – from professionals looking for ways of bulk-producing the same sour hit every time to amateur at-home bakers seeking bread’s roots – to create their own sourdough, to their own specifications.

Detailed text and photos will help the reader to navigate the whole process of developing a sourdough, explaining various methods and giving a wide range of recipes to follow, in addition to providing a blueprint of how to adapt commercial yeasted recipes into sourdough. An exploration of different techniques will help to build confidence and knowledge, fully equipping the reader with the right tools for their sourdough journey. Also included is a full explanation of what a sourdough starter is and how to build the best one suited to the individual baker’s needs – what to do if it goes wrong, how to look after it, and how best to maintain it.

Sourdough does not have to be a traditional loaf with a hearty crust. Sourdough croissants are a revelation, as is sourdough focaccia, ciabatta, and indeed the sourdough version of anything else that would otherwise be created using dried or baker’s yeast. This book will enable you to be creative and encourage you to be brave. With a bit of experimentation, the results can be hugely rewarding. Step-by-step recipes will show you how to utilize sourdough in all types of baking. There is even a gluten-free section – sourdough is a sensory experience that can be shared by all!

There is a handy trouble-shooting guide at the end of the book. It is based on my years of experience of teaching people, either in groups or in one-to-one situations, and being bombarded with questions that start with ‘What if…’ or ‘But mine…’.

What qualifies me to teach and write about this subject? I have been baking bread for over thirty years, and sourdough for around twenty-five. My journey started with leaving school in the mid-eighties with very little motivation or ambition. Coming from a mining village in the north of England during the miners’ strike of Margaret Thatcher’s tenure as Prime Minister, I had no real career direction other than wanting to be an actor. I was offered a job as a baker’s apprentice in the local village bakery and took to it immediately. It appealed to me so much that, by the time I was in my early twenties, I had travelled around France and worked with vigour and interest in a bakery in the south of the country. It was here that I became completely captivated by the amazing breads created without baker’s yeast! These breads were produced using what I could only describe as a grey sludge that lived in a big cast-iron bath. At certain times of day, it seemed to burst into life and bubble and grow. It was here that I came to learn that this was the ‘real’ yeast – the wild yeast that this bakery had cultivated for over forty years. Amazingly, until that time, although I had worked in bakeries for a number of years, I had not seen or baked with anything like it. It fascinated me beyond belief.

Close-up of a sourdough made with love.

My baking expertise developed over the following decades as I managed a number of bakeries both large and small, both artisan and factory. The baking experiences were varied but the one constant was sourdough – I wanted to incorporate it into all manner of baking and spent a few years in New Product Development for bread, where I studied the process of creating a starter that could be managed en masse. The aim was to keep and maintain over a tonne of it at a time, but this just was not feasible. Despite many trials, sourdough is not yet ready for mass production on quite that scale. Perhaps every sourdough product should really be hand-crafted, with the baker feeling at one with the dough. My belief is that sourdough is not something to be mass-produced and packaged to go on the supermarket shelf alongside a thick square toasting loaf that will last for more than seven days.

My wife and I then took the brave decision to set up a bakery of our own. This is where I first made my own sourdoughs, ranging from Marmite sourdough rolls to sourdough pain au chocolat. I loved it so much that I spent around eighteen hours a day perfecting my craft. We very quickly grew into a wholesale supply bakery that also taught bakers and novices alike how to bake bread. It was during these years that I fell in love with teaching – sharing my knowledge, enthusiasm and passion for all things bread, and in particular sourdough. An increasing desire to share my knowledge brought me to the world-renowned baking school in Borough Market in London, England, where I now teach across five days a week to around 130 people. About half of them are sourdough enthusiasts, while the other half are new to the wonders of the world of sourdough and fermentation. Hopefully, my wide-ranging experience and knowledge will help to guide you on your own sourdough journey, whatever that may turn out to be.

Perfecting my presentation techniques in the early days of my sourdough discoveries.

CHAPTER 1

THE HISTORY OF SOURDOUGH

The history of sourdough is, in fact, the history of bread. Any discussion of the origins of bread itself must involve a consideration of bread’s roots within sourdough.

WHERE DID SOURDOUGH COME FROM?

The first question to be asked is, ‘Where did sourdough come from?’ What is it that makes sourdough the original, and most natural, process of bread-making? It all comes down to wild yeast.

Wild yeasts are organisms that live everywhere. They thrive in the atmosphere, in water, on human skin, and in the air that is inhaled by people every single day. When wild yeast organisms encounter water and flour, a fermentation process begins. The organisms combine with the natural sugars and starches within the flour, in conjunction with lactic acid bacteria. Once the lactic acid and wild yeast come into contact, they both fight to survive and grow into that ecosystem; the by-product of this is carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide produced then generates the prove in the dough, by expanding the space that the dough takes up. This process, on a basic level, also creates the sour ‘bite’ in the taste of the resulting bread. Although the science behind sourdough is essential in the creation of its unique taste, the at-home baker does not need a complete understanding of it, in order to use it to enhance homemade bakes.

Wild yeast in the making, cultivated in a Kilner jar.

With this chemical reaction, the history of sourdough began. However, researchers can only speculate as to the exact time when people began using wild yeast cultures to generate volume in the breads they produced. What is now known, though, is that experiments with grains as a food source have been taking place for longer than people originally thought. As recently as 2009, Julio Mercedear, an archaeologist working for the University of Calgary in Canada, and his team, whilst excavating grinding stones, found the residue of sorghum (a gluten-free flour) still embedded within them. These finds were hidden deep within the caves around Mozambique; on closer examination, it was determined that they pre-dated even the Agricultural Big Bang, being around 100,000 years old. It seems that, technically, gluten-free is not the new phenomenon that people perceive it to be.

The shift from man being a hunter-gatherer to being a farmer happened sporadically around the globe. Each continent naturally selected its own indigenous seeds to harvest. These ancient grains were spelt, mostly farmed around central Europe; khorasan, from Iran, Afghanistan and central Asia; emmer, Europe and Asia; rye, central Europe; millet, Africa and south-east Asia; and sorghum in Africa, India and Nigeria, to name but a few.

Historic kisra flatbread.

The first breads were, undoubtedly, unleavened flatbreads. These were made using only flour and water mixed into a porridge-like paste, then poured on to a heated stone to bake. The Sudanese, to this day, still make a flatbread with sorghum flour and wild yeast, known as kisra. The Ethiopians produce another flatbread, with teff flour, called injera, using a similar process to that of the Sudanese kisra, but with the aid of fermentation (using wild yeast). A similar outcome can be achieved by baking the flatbreads on a large river rock outside on a wood-burning fire, and the results can be remarkable. This process enables the baker to enjoy the unmistakable aroma of the bread baking, and to embark on a multisensory journey involving the palette – something that has to be experienced to be believed. Sadly, the introduction of the enclosed oven has removed this vital piece of the jigsaw from the whole experience of baking fermented breads. This is one of the few developments in the history of sourdough that could be interpreted as a regression. Although the change from open to enclosed ovens has allowed mass production, and the development of timings, structures, and so on, it is a must for the modern baker to try the old, open method. It provides another level of understanding of the impact of different baking processes on flavour – something that is not always considered.

Flatbread in an outdoor tandoor oven.

WILD YEAST

Although there is no definitive answer as to why using a wild yeast culture in breads started, it is possible to make an educated guess. As human beings planned and organized their lives, they inevitably looked at making more food than was necessary simply to give sustenance for a few days. Unwittingly, in doing so, they discovered that leaving bread mixtures aside for several hours, if not days, would allow wild yeast to permeate the dough. The result was an increase in the volume of the breads. With this came much-improved textures and taste and, overall, a more palatable product.

One of the oldest sourdough breads to be excavated, in Switzerland, dated back to 3700BC. The Ancient Egyptians also discovered and recorded the use of leavening by means of a wild yeast culture. Hieroglyphs showing the production of bread, and even a few bread recipes, were often accompanied by images depicting the brewing and consumption of alcohol. Clearly there was a link between the two processes as long ago as 3000BC.

THE HISTORY OF BREAD (AND BEER)

The Earliest Beers

The history of beer is linked to the birth of civilization. It was discovered as soon as our ancestors decided to settle down. The earliest evidence of Man drinking beer is found in a pictogram on a seal dating from the 4th millennium BC. Discovered in Tepe Gawra (in modern Iraq), a settlement in ancient Mesopotamia, it shows two figures drinking from a large jug through straws. Of course, what they are drinking would have been quite unlike the beer of today. It was more like a soup – a blend of water and grains – and it would have been swimming with chaff and other impurities, which is why it was drunk through cane straws. Beer also appears on the oldest written testimony of human civilization – the tablets from Uruk in Mesopotamia (also in modern-day Iraq). The beverage was represented in Sumerian script by a jug crossed by two parallel lines. Archaeologists have also found many tablets containing lists of names, accompanied by the inscription ‘issued his daily ration of beer and bread’. These ‘payrolls’ are the source of a great deal of information about our ancestors’ diets. As writing developed, the symbol representing beer became more abstract. This can be seen in the cuneiform script, which is a precursor of the Roman alphabet.

The beer revolution began, as might be imagined, where the agricultural revolution began, that is to say, in the region known as the Fertile Crescent. This was an ideal location for founding settlements and cultivating wheat. Our ancestors discovered that grains tasted better when pounded and mixed with water, and that they were even more palatable when the water was heated. Shortly afterwards, they discovered another of wheat’s virtues – it could be stored for months or even years without losing its nutritional properties. The ancient civilizations began to construct storage houses for their grain and attached greater importance to the harvest. They also invented tools, including sickles, woven baskets and quern stones for grinding, which made their work easier. With these developments, they bid farewell to the constant fear of starvation that had caused them to lead their migratory lifestyle. From this point onwards, men and women were able to settle down and start keeping watch over those grain storehouses.

The developmental stages of an early starter.

As time passed, it became clear that grain soaked in water would begin to sprout and take on a sweet taste. (Today, it is known that this is caused by amylase enzymes, which convert starch into maltose.) This is how malt came into being. When left to stand in water at room temperature for a few days, it begins to fizz and, when drunk, it can trigger a pleasant state of intoxication. Of course, our beer-supping ancestors did not know the science behind the process – under the influence of yeast that could have existed naturally in the air, sugar ferments and alcohol is created. After beer had been discovered, people learned through trial and error that the more malted barley they added, and the longer it was left to ferment, the stronger the drink became. Ancient brewers also observed that, if the beer was brewed in the same vessel, it was better. This of course happened because there were residual yeast colonies in cracks in the vessel, so fermentation occurred more swiftly.

One theory claims that beer is older than bread, positing that the first cake, the great-grandfather of bread, was created from spilled fermented beer, which was then dried and baked on a hot stone. Beer in those days was a watery mush created from saturated fermented grains, so, although it has never been confirmed, the theory will surely strike a chord with every beer drinker.

Most of the information we have about the history of beer has been left to us by two civilizations who used writing systems – the Sumerians and the Egyptians. Interestingly, beer was drunk by a group of people from a single jug using a long straw, even when individual vessels were available. Clearly, beer drinking already had a social aspect – it was a ritual and a manner of sharing provisions. The state of intoxication following the drinking of beer also had its mystical aspect in many cultures. Beer was believed to be a gift of the gods. The Egyptians claimed that it was Osiris, the protector of crops, who one day created a mush from water and sprouting grain. Being busy with other matters, he forgot about it and left it for a few days in the sun. When he returned, he saw that the drink had fermented, and he decided to drink it. The god felt so fantastic that he decided to share his invention with people. The Egyptians often used beer in religious ceremonies, as well as during funerals and festivals associated with agriculture.

We have the Sumerians to thank for the earliest example of world literature, the Epic of Gilgamesh. It contains the story of the bestial giant Enkidu, who, after drinking beer, ‘washed his body and shed his fur so as to become a man’. In Mesopotamia, knowledge of beer and bread was something that separated civilized people from those who were ‘wild’. The Egyptians left us the inscriptions in the Pyramid Texts of the rulers of the 4th and 5th Dynasties. They not only used writing to describe mighty deeds, but also mundane trade transactions. In fact, beer is the most frequently mentioned foodstuff in these early examples of writing. Beer was basically a currency that was also easily divisible. Records show that, during the construction of the pyramid complex at Giza, the workers got four loaves of bread and around five litres of beer a day. ‘Bread and beer’ naturally became a symbol of wealth. When the Egyptians become reputable brewers, they began to export their beer around the world.

Beer was also recommended in Egypt as a medicine and as a base for other medicaments, and it was regularly prescribed for both women and children. It was indeed healthier than the alternative – it contained fewer micro-organisms than untreated water from the Nile, because it was partially composed of alcohol. In addition, during its production process, the water was heated to a relatively high temperature. This was usually done by heating stones in a fire and throwing them into the mix.

Bread and Beyond

Agriculture, combined with the milling process to make flour, created the building blocks to form a new civilization. The change to agriculture took a huge amount of organization and care; farming was not a one-man operation, but a team effort, with people coming together, each with his or her own individual role to play. However, with progress and efficiency, it became possible to produce more than each settlement of people needed for their own use. As a result, members of civilization began to develop into traders. This required some form of written record for stock levels and growing seasons, as well as maths, for calculating volume and yield. In addition, some form of currency was needed to trade with. As the traders began to achieve success, a divide between the affluent and the poor developed, and there came a need to protect the assets of the wealthy. The natural progression was to form the first armies.

Settlements developed their own different trades – field workers, millers and, essentially, bakers to bring the product of their toil all together in the bread. Those settlements evolved into villages and towns, then cities, with bread production playing a vital part in building the societies in which we live today. A number of archaeological discoveries have proved the historic influence of this valuable food source. Large bakeries excavated alongside the Pyramids of Ancient Egypt would have helped to deliver the large intake of carbohydrates needed to sustain the building workforce, again reflecting the significance of bread. Easily transported and easily stored, with an extraordinarily long shelf life – when kept in the correct conditions – grain has been vital for many centuries to ensure that people have not gone hungry.

‘The Sour Doughs’

In the 19th century, Gold Rush prospectors came to California to make their fortune. These bands of brothers, just like the Egyptian workforce, needed food that provided them with energy-releasing nutrients – a good intake of carbohydrates was important. Fortunately, the Gold Rush migrants were aware of how to create bread from a wild yeast culture. According to anecdotes, the prospectors would even sleep with their cultures, keeping them nice and warm, to encourage fermentation. A sourdough starter has always needed devoted care and attention; in California, it was crucial to the survival of the prospectors. If their starter died, they would lose their main source of carbohydrate – and thereby their main source of nutrition. Caring for the starter could be a matter of life and death.

The prospectors quickly earned the nickname ‘The Sour Doughs’, after their breads. In the second year of the Gold Rush, 1849, the Boudin Bakery was opened in San Francisco by Isidore Boudin, son of a master baker in France. The bakery continues to thrive today, still producing a world-famous (and trademarked) product known as ‘The Original San Francisco Sourdough’. According to local bakers, sourdough bread made outside a 50-mile radius of San Francisco tastes different, less sour. Tests carried out in the 1970s on the lactobacilli bacterium, a major player in the success of a sourdough, concluded that it was indeed special. It had not yet been catalogued, so it gained the name L. sanfraciscensis. However, it later turned out that the bacteria were not quite as unique as first thought and can be found in bakeries across France and Germany.

YEAST

Wild yeast was king for thousands of years, until brewer’s yeast came flying on to the scene. Even before Louis Pasteur’s advanced methods of culturing yeast gave the world a better idea of the fermentation process, a Dutch distiller in 1780 started marketing yeast foam to bakers. It was made by skimming from the top of fermenting alcohol. The process was refined by a Vienna factory in 1867, which removed the yeast foam, filtered it and dried it into compressed cakes. In 1872, the Vienna Process, as it was known, was developed by Charles Fleischmann into an active dry yeast.

The production and development of yeast was moving fast. It was a godsend for bakers and allowed production to move forwards, enabling bakeries to create and produce on a vast scale. Commercial active yeast was fast and reliable, and, with Fleischmann’s development, there seemed to be no need to go back to a wild yeast culture.

MOVING TO MASS PRODUCTION

Human beings are impatient; always striving for a better and easier way of doing things; maybe this is why humanity has been so successful, evolving from hunter-gatherers to farmers, and building a civilization on grain. The milling process went through many advancements. From the prehistoric method of grinding the seeds into flour with a rock, via the rotary quern (dating from around 300bc, the Romans took milling to another level around the 1st century ad, building the Barbegal water mill in France, which could produce 4.5 tonnes of flour a day. Farming methods were also developing rapidly. Originally, agriculture was hugely labour-intensive, requiring time and financial investment, but, with the introduction of steam, machines could replace horses to do the bulk of the work. This, along with the introduction of crop rotation and pesticides, enabled farming to become faster and more cost-effective.

Once the Industrial Revolution came along, the ensuing scientific developments moved the industry closer to the holy grail of bread: a bread that bakers had been striving for since first hitting a rock on seed. The one final component that would make this a reality finally appeared in the 1960s, when the British developed the Chorleywood Process. This allowed the mixing of dough at a high speed, and the inclusion of a combination of extras such as Vitamin C, emulsifiers and enzymes. Bakers could use lower-grade flours and the industry could now make bread from start to finish in just three hours. The same process is still used today in mass production. It was a massive revolution and played a significant part in bringing down the cost of bread for the consumer. The downside is that, in the speeding-up of the process, the fermentation period has been significantly reduced. This is the part of the process that allows the dough to build flavours. It is time-consuming but crucial in the development of the taste of the bread.

The dream of mass production had become a reality, and the world’s industrial bakers could revel in the appearance of such products as ‘Wonder Bread’, as American white sliced loaf. Gone were the sour undertones and the chewy textures – but also gone was the flavour! The masses had spoken and they had chosen convenience and cost over flavour. In the mass-production industry, this type of product was not even given the name of bread; instead, it was known as a ‘sandwich carrier’. The name says it all; this bread was no longer a source of nutrition and taste, but merely a vehicle to transport a filling from plate or packet to mouth! And nobody was mourning the death of sourdough – the death of a depth of flavour to bread. The new generation of breads were hailed as hygienic, pure and healthy. The product was promoted as an energy builder, and even as an aid to weight loss! The original combination of flour, water and yeast had made so much progress, but it had lost so much along the way.

THE ARTISAN MOVEMENT

In the 1970s, questions began to be asked about the health claims made by ‘Wonder Bread’, and rumblings were beginning in other quarters too. World-renowned French baker Raymond Calvel voiced his concern about the dire quality of bread in France, while the American writer Henry Miller famously wrote that ‘you can travel 50,000 miles in America without tasting a piece of good bread’. In 1974, Edward Espe Brown published a revolutionary book entitled The Tassajara Bread Book. Written by a Zen Buddhist teacher at the Tassajara Zen Mountain Center in California, this book offered its readers a more soulful approach to bread-making. It returned to older methods of making and baking and re-introduced the main component: wild yeast! During this period, independent mills also started to pop up, among them Bob’s Red Mill, in California, which was established in 1978 by Bob and Charlee Moore. Bob Moore’s driving force for healthier options started with the death of his father as the result of a heart attack at the young age of 49. The first mill opened in Redding, California, and was at the forefront of a seismic change around California, where people were looking for a healthier way of living. The Artisan Movement was now in full swing, and many great bakers took up the baton: Peter Reinhart, Chad Robertson, Lionel Poilâne, to name just a few.

The Artisan Movement sought to return to the older methods of bread production, using starters, sponges, poolish and pre-ferments, along with old dough. The aim was to get back the flavour that had been missing from mass-produced breads, and the truth was the Movement was able to come up with much better results than had been achieved prior to the Industrial Revolution. By the 1970s, bakers had gathered more information about the power of pre-ferments and such like, and were developing much better-tasting breads; and this time it was out of desire, not necessity. The classic French pain de campagne was one bread that was developed in the booming 1970s, while ciabatta first appeared in 1982, produced by a baker from Verona, who wanted to create an Italian rival to the mighty French baguette. Although it is relatively recent, many believe ciabatta to be an ancient bread, perhaps because, with the intense specificity of its flavour, it clearly has its roots in the old methods.

Example of a historical pre-ferment.

SAFEGUARDING SOURDOUGH FOR THE FUTURE

Man’s history and relationship with bread runs deep. It seems that there is no other food source that stirs up as much emotion. When there is a shortage of bread products, the public are not happy; there have been countless bread riots around the world, and it has even played its part in revolution! Mistakes have been made by the baking industry, but lessons have been learned and the industry is now looking back to the past for inspiration. Society has changed and increasing numbers of consumers now want integrity, traceability, health and taste. It represents a big shift from a culture of convenience and low cost. After all that history and development, bread is now in the best place it has ever been when it comes to sourdough. The flavours are back, and the structures have been perfected. We are now closer than ever to the original method of enhancing the taste of bread, whilst having progressed a long way in terms of our understanding of how to develop it.