Ballad Tales E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

A ballad is a poem or a song that tells a popular story and many traditional British ballads contain fascinating stories – tales of love and jealousy, murder and mystery, the supernatural and the historical. This anthology brings together nineteen original retellings in short story form, written by some of the country's most accomplished storytellers, singers and wordsmiths. Here you will find tales of cross-dressing heroines, lusty pirates, vengeful fairy queens, mobsters and monsters, mermaids and starmen – stories that dance with the form and flavour of these narrative folk songs in daring and delightful ways. Richly illustrated, these enchanting tales will appeal to lovers of folk music, storytelling and rattling good yarns.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 300

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

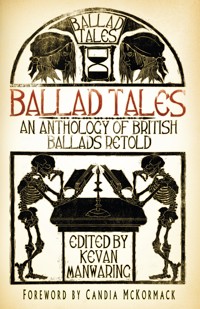

BALLAD TALES

to dance

BALLAD TALES

AN ANTHOLOGY OF BRITISHBALLADS RETOLD

EDITED BY KEVAN MANWARING

FOREWORD BY CANDIA MCKORMACK

First published in 2017

Illustrations by Kevan Manwaring, 2017

Cover illustration by Andy Kinnear, 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

© Kevan Manwaring, 2017

The right of The Author to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8319 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Candia McKormack

Introduction by Kevan Manwaring

1. Janet and the Queen of Elfland

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘Tam Lin’ by Fiona Eadie

2. The Tongue that Cannot Lie

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘Thomas the Rhymer’ by Kevan Manwaring

3. Mary and Billy

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘The Pretty Ploughboy’ by David Phelps

4. The Storm’s Heart

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘The Grey Selkie of Sule Skerry’ by Chantelle Smith

5. The Darkest Hours, The Deepest Seas

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘The Cruel Ship’s Carpenter’ by Richard Selby

6. Nine Witch Locks

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘Willie’s Lady’ by Pete Castle

7. The Dark Queen of Bamburgh

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘The Laidly Worm of Spindlestone Heugh’ by Malcolm Green

8. What Women Most Desire

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘The Marriage of Gawain’ by Simon Heywood

9. The Droll of Ann Tremellan

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘Ann Tremellan’ by Alan M. Kent

10. The Pirate’s Lament, or A Wild and Reckless Life

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘The Flying Cloud’ by Eric Maddern

11. The Shop Girl and the Carpenter

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘The Bristol Bridegroom or, The Ship Carpenter’s Love to a Merchant’s Daughter’ by Laura Kinnear

12. A Testament of Love

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘Sovay’ by Karola Renard

13. ‘There Ain’t No Sweet Man’

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘The Famous Flower of Serving Men’ by Kirsty Hartsiotis

14. Shirt for a Shroud

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘Scarborough Fair’ by Nimue Brown

15. The Grand Gateway

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘Barbara Allen’ by Mark Hassall

16. Mermaid in Aspic

A Retelling of the Ballads ‘The Twa Sisters’, ‘Binnorie’, and ‘The Bonny Swans’ by Chrissy Derbyshire

17. The Wind Shall Blow

A Retelling of the Ballads ‘The Three Ravens’ and ‘The Twa Corbies’ by David Metcalfe

18. The Migrant Maid

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid’ by Anthony Nanson

19. The Two Visitors

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘The Twa Magicians’/‘The Coal Black Smith’ by Kevan Manwaring

The Contributors

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all the singers, collectors and listeners of these ballads.

‘The Laidley Worm of Spindlestone Heugh’ by Malcolm Green was previously published in Northumberland Folk Tales (The History Press, 2014).

All illustrations by Kevan Manwaring.

Foreword

Selkies, storms, sorcery, seduction … this is the language of the ballads that have been passed down to us from generation to generation.

The lilting rhythms of the poetry have woven their way into our psyches, enriching our appreciation of the land and giving a deeper understanding of our ancestors. There is magic all around us, of course, but it is often drowned out by the din of technology, hidden from view as we choose to watch our lives unfurl through the reflection of an ever-darkening black mirror.

There is a certain charm to the telling of tales, to the act of listening – really listening – and of retelling through song and speech, with the nuances that arise with each rendition. As music is recorded, uploaded, downloaded and shared, there is the temptation for others to create a faithful rendition – tutorials provide musical notation, lyric sites make sure you’re word-perfect, there are even computer games that reward you for how closely you adhere to the original! Really, though, the ‘tribute band’ generation is taking its final bow and standing aside for a people who care about the art of storytelling, care about musicianship, and care about the joy of gently unravelling the cloth woven by storytellers before and creating something beautiful, entwining old threads with new. This cloth carries the fading colours of the old, while weaving in the bright-hued yarn of the new; ever changing, with respect for what’s gone before while celebrating the excitement of what’s yet to come.

Introduction

A collection of ballad tales might, on the surface, seem redundant – the very term could be thought of as tautological. Surely a ballad, in essence a narrative-in-song, ‘a folksong that tells a story’, is a tale in itself and requires no further retelling? Well, there are indeed many fine ballads that can be listened to and enjoyed for their own sake – a good cross-section are referenced in this anthology, and either before or after reading the respective prose retelling I recommend that you check out a selection of recordings from the archives and from modern musicians. You will perhaps be surprised by the number and diversity of the versions on offer – with different lyrics, melodies, and arrangements – none of which ‘break’ the original, if indeed such a thing exists. There is rarely an urtext or master tape for a ballad – even if we go by the oldest known recording, others may yet emerge. And you can guarantee that the version recorded at that precise point in time was just that – a snapshot of an ongoing process, one with deep roots and ever-growing branches.

For a ballad to be ‘traditional’ it is usually required to be anonymous and of perceived antiquity, although in actuality all ballads were written by somebody, somewhere, somewhen, and many were penned in the late nineteenth and twentieth century. Indeed, contemporary folk practitioners occasionally find their own song assimilated into the folk tradition and thought of as ‘trad’ – a category error considered an accolade by some. David Buchan, in The Ballad and the Folk (1972), offers one definition of a ballad as ‘a narrative song created and re-created by traditional oral method’, although he recognises the problems inherent in the notion of oral tradition and is careful to nuance his definition later into various subcategories (oral texts; oral-transitional texts; chap-transitional texts; chap texts; modern texts; and modern reproductions of these), even though he acknowledges Francis James Child’s warning: ‘Ballads are not like plants or insects, to be classified to a hair’s breadth’. Perhaps the best approach is a practical one. As Steve Roud, author of several books on folklore and folk music, including The New Penguin Book of English Folk Song (co-edited with Julia Bishop in 2012), quipped in a Folk Tale Symposium held in Stroud in September 2016, ‘a folk song is a song sung by a folksinger’.

I began researching folk songs, their collectors, and the nebulous processes of the oral tradition, as part of a Creative Writing PhD at the University of Leicester. The collection process can never be infallible or completely comprehensive (due to the collector’s expectations, research ethics and social skills, their competency at transcribing lyrics or music accurately, the performer’s memory, and other mitigating factors – the presence or absence of family members; work; illness; class; religion; ethnic and national prejudices). Something is always missed. For example, when Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles (leading figures in the folk-song revival of the early twentieth century) visited the tradition-bearer Jane Hicks Gentry in Hot Springs, North Carolina, in 1916, he and Maud diligently collected her amazing repertoire of ‘love songs’ (as ballads were commonly called in the Appalachians) but completely missed her rattle-bag of Jack-Tales, which were simply not on their radar. It would take future collectors to acquire these.

Such blind spots within any specialist field are common, so it not surprising to see them occur in the folk music and storytelling scenes: folk festivals seldom book storytellers, and never give them prominent billing, however established they might be. Storytelling festivals are rarer and perhaps more keen to have the crowd-pulling power of established folk music acts; but storytelling clubs, although often open to musicians, generally don’t encourage the democratic singarounds or ‘sessions’ that you get in folk circles. And the two audiences, demographically almost indistinguishable, seldom mix. Although both undeniably part of the oral tradition, they seem at times to exist in separate universes, albeit with notable exceptions (e.g. Hugh Lupton and Chris Wood; Daniel Mordern’s troupe, The Devil’s Violin; British-Bulgarian performing arts group, A Spell in Time; or Richard Selby and Beth Porter’s collaborations in the Bath Folk Festival to name a few). This seems to me to be to their mutual impoverishment, because enthralling cross-fertilisation can occur, as I’ve experienced in the group I co-founded, Fire Springs, and more recently with my partner, Chantelle Smith, in our ‘ballads and tales’ duo, Brighid’s Flame.

In truth, folk music and storytelling exist in a fertile continuum, which practitioners on both ‘sides’ revel in, and the forms are far more porous than less open-minded promoters, publishers or producers would have us believe. Those with vision, the artistic innovators and the bold programmers, are always challenging such arbitrary walls.

So, with such a locus of interest (in particular my research into ‘supernatural ballads’ of the Scottish Borders) I became interested in the possibilities of narrative treatments. Having written two collections of folk tales for The History Press’ county-by-county series (Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire), and contributed to The Anthology of English Folk Tales (2016), I had already written a handful of ‘ballad tales’ – that is creating a folk tale out of an existing ballad. I knew I was not alone in this and I felt the form could be pushed further.

While the Folk Tales series emphasises the orality and aurality of the text, pre-empting the tales as potential resources for future performances, here I wanted to explore the literary possibilities alongside the performative. My Ballad Tales would be free to experiment without any expectation or performance of authenticity. So I pitched my idea to the publisher and the rest is history (press), as they say.

I invited writers and musicians whom I thought would fit the anthology well. Although I reached out to practitioners across the country and across disciplines the process was no doubt skewed by my own predilection: those whose oral, literary or musical skills I know and admire; who I have had the pleasure to collaborate with or see in action. That the contributors are largely a result of such elective affinities is perhaps inevitable and I make no apologies for that, but hope that if future anthologies result I will cast a wider net and hope for an even healthier diversity of voices.

I asked for imaginative, lateral retellings in prose of traditional British ballads – now those last three terms can all be deconstructed until the cows come home, but that is not our focus here. Basically, I was looking for pre-twentieth-century anonymous ballads from the British Isles (not ‘ballads’ in their strictly poetical form, or as a pop song, but as robust tale-songs from Judas, the earliest known ballad dating from AD 1300, onwards). This undoubtedly narrowed our scope, but makes an anthology like this possible. Other iterations might focus on different countries or themes.

Yet this seemingly narrow remit almost immediately was subverted by the submissions. Australian-born Eric Maddern’s rollicking telling of the wide-ranging ballad of the Flying Cloud, ‘The Pirate’s Lament, or A Wild and Reckless Life’, is perhaps the greatest exception to this rule as it roams the Seven Seas (being found in versions from the Low Countries to Scotland, Newfoundland to Nova Scotia and across North America), rightly challenging the questionable, Colonialist notion of an exclusively ‘British’ ballad – for a ballad, by its very form, memorable, copyright-free and travel-proof, is a moveable feast.

With each singular submission my notion of a ballad tale was expanded. I deliberately kept the brief open-ended. I did not wish to be prescriptive or to influence the way the writers went with their material. They chose their ballad; they chose how to adapt it. Perhaps it was a controlled experiment on my part – to see what the contributors would come up with independently – but it paid off. There is a splendid array of ballad tales here, ranging from the more ‘traditional’ approach, where the balladeer has worked with the grain of the ballad; to the more ‘experimental’ approach, in which the genre, gender, moral compass or plot of the original is completely subverted. That is not to say that the innovation only happens chronologically (as though to claim: the greater the distance, time-wise, from the original setting, the more innovative it is) as daring and dramatic volte-face can happen in any aspect of a ballad tale – in the nuances of characterisation (‘Tam Lin’; ‘The Storm’s Heart’), dialogue (‘The Darkest Hours, The Darkest Seas’), use of dialect (‘The Droll of Ann Tremellan’), or telling detail (‘Mary and Billy’; ‘Nine Witch Locks’), to list but a few.

A tale told well enough transcends time.

It is perhaps no surprise to note that a few of the ballad tales feature cross-dressing (‘A Testament of Love’; ‘Ain’t No Sweet Man’; ‘The Shop-Girl and the Carpenter’), not due to a wish to jump on any fleeting bandwagon, but due to the simple, regrettable fact it is hard to find traditional ballads in which the female protagonist has agency, can act rather than be acted upon, and enjoys equal status to the male characters. That each respective tale is distinctive in tone and setting shows how even with similar sources good writers can conjure something original. And in terms of gender politics, such concerns are very timely and unfortunately perennial as two of the oldest stories in this collection (‘What Women Most Desire’, from the fifteenth-century poem, ‘The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Lady Ragnelle’; and ‘The Dark Queen of Bamburgh’, based upon ‘Kemp Owyne’) show.

The later tales in the collection (‘A Mermaid in Aspic’; ‘The Grand Gateway’; ‘Shirt for a Shroud’; ‘The Wind Shall Blow’; ‘The Migrant Maid’; ‘The Two Visitors’) illustrate in daring ways how the form can be recast in a contemporary or even future setting while still retaining its core truth. Here be dragons and mermaids (and men) in many shapes and forms.

To say much more than that might undermine the pleasures that await you. Each balladeer has offered accompanying notes, but I suggest deferring that gratification until after reading their tale. The Child and Roud Indexes have been used to reference each ballad (e.g. ‘Child 37/Roud 219’), which you will find in the accompanying notes at the end of each chapter. These indexes are available online.

Now, pour yourself a glass and pull up a chair. You are in the company of bards and the hearth-fire is lit. In the dance of the flames glimpse those who’ve remembered and collected before us; in the hiss and crack of logs, hear the voices of those whose songs we tell.

Kevan Manwaring, Stroud, 2017

1

Janet and the Queen of Elfland

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘Tam Lin’ by Fiona Eadie

O I forbid ye, maidens a’, That wear gold on your hair, To come or gae by Carterhaugh, For young Tam Lin is there.

ANON, Scottish Borders

Long ago, in the borderlands between England and Scotland, there lived the Earl of March. His land covered moor and hillside, glen and trickling burn, but there was one place on his estate where people feared to go – and that was the well and the wood at Carterhaugh. Since ancient times it had been told that Carterhaugh lay within the fairy realm. The older people would say to the young, ‘Do not go to that place, for if you do you will surely be spirited away and we will never see you again!’ If any had to go by Carterhaugh, if there was no option, they would take a token – to placate the others – and leave it at the well.

Now the Earl had one bonny daughter, Janet. Strong, proud and feisty, she had reached an age where she was becoming restless and curious to know more of the world beyond her father’s castle.

One morning in late summer, Janet sat looking out of the castle window, as the sun warmed the old stonewalls, the smell of heather floated on the breeze and the gentle hum of bees drifted in the air. In the distance, the blue haze of Carterhaugh woods beckoned.

‘I will go there, I will,’ Janet thought to herself. ‘I will take a token and no harm will come to me.’

So she braided her hair about her head, she raised her kirtle above her knee and away she went. When she reached the well at Carterhaugh, Janet was enchanted. Soft grass grew all around, roses tumbled over the well and, beyond a small rounded green mound, hawthorn bushes shimmered in the sunlight.

Behind them the dark woods.

Janet took a brooch from her dress and laid it as a token on the rim of the well. Then she reached up and plucked a double rose, twined it into her braid and gazed down into the well to see how she looked.

As Janet straightened up, she felt a shadow fall across the water, blocking out the sun. An involuntary shiver became a shudder of alarm as she saw there on the other side of the well, glaring at her, a young man clothed all in green holding the reins of a white horse. The man’s handsome face was stern, even angry, and when he spoke his voice was harsh: ‘How dare you pluck that rose, lady, without my leave?’

‘This wood is my father’s; it is my very own! I do not need your leave, young man. And who are you, who haunts the well at Caterhaugh?’

‘My name is Tam Lin. I am a knight from the court of the elfin queen. When you picked that rose, you summoned me.’ They stared in fierce disdain at one another for a long time, both of them angry at the trespass and disturbance of the other. Then, unbidden, a force rose beneath that anger and something else was kindled between them.

Something strong and deep and sweet.

And so it was that Janet tarried at the well. And so it was that, as the summer afternoon progressed, they lay together – maid and knight – in the soft grass beside the well. And so it was that presently they slept.

When Janet awoke, Tam Lin had gone, a chill ran in the air and all the woods grew dim.

In the days and weeks that followed, Janet could think of little else except Tam Lin. Who was he? What was he? How could she see him again? She did want to see him again. Unwell and worried, she went to the oldest of her serving maids, who noticed her mistress’s pallor and that her shape was subtly changing.

‘I think my lady’s loved too long and now she goes with child,’ observed the maid.

Janet blushed.

‘I know a herb, lady, grows in the wood at Carterhaugh, that would twine the babe from thee …’

So Janet braided up her hair about her head, she raised her kirtle above her knee and away she went. She passed the well, she reached the wood and, as she bent to pick a small grey herb, Tam Lin appeared.

‘Oh, do not pick that herb, my love. Do not think to kill the babe that we got in our play!’

‘Who are you, Tam Lin? What are you? Are you an elfin knight or are you a mortal man?’

Tam Lin replied, ‘I was born a mortal man, grandson of the Earl of Roxburgh, and christened the same as you. One morning as I rode out by Carterhaugh, my horse stumbled and threw me onto yonder green mound where I lay senseless. The Queen of Elfland found me there and took me down into her realm to dwell, to be her knight.

‘At first I liked it well enough, I was the queen’s favoured knight and I had almost forgotten my life in this world but when you summoned me I returned and I remembered. After we lay together I knew that I want only to live once again in the mortal realm, to be with you ... your husband and a father to our child.’

‘Well then Tam Lin, what must be done to win you back?’

Tam Lin was silent then for a long while and when he spoke again it was in a voice of despair.

‘There is only one way to win me back and that so fearful I do not know if I can ask it of you.’

‘Tell me Tam Lin, what must I do?’

‘Tomorrow night is Halloween, when the veil between this world and the fairy realm is stretched thin. On that night, as every year, the elfin court will ride. Every seven years they pay a tithe to hell and I fear that tomorrow – for all that the queen makes much of me – I will be that tithe. If you would win me back you must wait by the well at Miles Cross at midnight. You will see the elfin host pass by – first will come the queen herself and then two companies of knights. Then will ride by a black horse, then a brown horse and finally a white horse. I will be riding the white horse and you will know me because I will have one hand gloved and one hand bare. You must pull me down from my horse and hold me fast. When the queen sees what has happened her wrath will be terrible and she will change me in your arms into all manner of fearsome beasts. If you can but hold me fast, you will not be harmed. Finally, she will change me in your hands into a red-hot coal. Take this burning coal and throw it into the well and I will be returned, naked, to the mortal world. Cast your cloak over me and keep me safe until the elfin host has gone.’

The following night, an hour before midnight, Janet left the castle. Clouds scudded across the sky and the wind rustled among the trees. Although she had wrapped her thick cloak around her she was shivering, as much with fear as cold. As Janet stumbled towards Miles Cross, it seemed that every root tried to trip her and every branch snatched at her face. Forms and figures flitted by her, shapes and shadows stole around her. Finally, she reached the well and, as she hid in the bushes there, the clouds cleared and the full moon cast a cold light over the woods and the deserted road.

At first she thought they would not come but then, as midnight approached, she heard a sound that made her blood run cold. From far off along the road came the unearthly sound of fairy bells on harnesses and Janet saw a faint and eerie light as the host approached. First, came the Queen of Elfland herself, her long black hair streaming in the wind, her face proud, fierce – and totally other. Then two companies of knights and behind them a rider on a black horse, a rider on a brown and, finally, on a white mount, a rider with one hand gloved and one hand bare. Janet rushed out from her hiding place and pulled the rider down. She covered him with her cloak and, as both stood shaking in the road, the queen suddenly became aware of what had happened. She wheeled her horse around, pointed at the pair and gave a terrifying cry that rang out across the night: ‘Oh, young Tam Lin’s away, away! Oh, young Tam Lin’s away!’

Suddenly, it was no longer a knight that Janet held in her arms. The queen had changed Tam Lin into a lion that roared and ripped and Janet thought her pounding heart would crack with fear. The rank smell of the beast, its strength and sharp claws threatened to overwhelm her but, somehow, she held on ... he was born a mortal man, he was born a mortal man she told herself over and over.

Then the queen changed him into a bear that clawed and crushed and Janet could feel its foul breath on her face. As terror flooded her whole being, she forced her quaking mind to focus on one thought: he was christened the same as me, he was christened the same as me.

The bear vanished and in its place a powerful and venomous snake twisted and twined in her hands. Paralysed with fear, muttering fiercely again and again he is the father of my child, Janet somehow held fast until finally the snake was gone and she was holding, instead, a red-hot coal. Beyond fear, beyond thought, Janet grasped the coal and she was not burned. She threw it into the well, there was a startling hiss and then, as she stared, a young man, naked, emerged from the water. She went to pull him out and once more threw her cloak around him.

At this the queen, in a voice of ice and fury, roared, ‘Had I known you would be taken from me, I should have took out your eyes Tam Lin and put in two eyes of wood! I should have took out your heart Tam Lin and put in a heart of stone!’

Then with an angry, imperious gesture to her followers, the queen wheeled her horse around and led the elfin host away. As the eerie light grew dim and as the sound of fairy bells on harnesses faded into the night air there was left in the road, in the moonlight, only Janet and Tam Lin, their arms about each other, shaking but alive – a mortal woman and her mortal man.

I first came across the ballad of ‘Tam Lin’ (Child 39A) thirty years ago on a vinyl LP by Frankie Armstrong – won in a folk club raffle. I was captivated by it and by Frankie’s voice and played that particular track over and over again until I knew the lyrics by heart. In the intervening years, I have heard many other versions but this is the one that has stayed with me and sits behind the Tam Lin story that I tell every Halloween.

2

The Tongue that Cannot Lie

A Retelling of the Ballad ‘Thomas the Rhymer’ by Kevan Manwaring

Syne they came on to a garden green, And she pu’d an apple frae a tree: ‘Take this for thy wages, True Thomas, It will give the tongue that can never lie.’

ANON, Scottish Borders

May I be so bold as to sit by your fire? It is a dreich nicht and I am weary from the hard road. Thank you kindly, good sirs. I knew you to be gate-gangers like mysel’. Such times drive us onto the road, do they not? Ah, uisge beatha … you are gentlemen! I’ve a lowin-drouth upon me. Slàinte mhath.

What’s that, you dinnae ken Scots?

Then I shall do my best to speak the Sassenach tongue, although I would fain from calling it the King’s English. Pisht. He may claim this whole land as his, but does Ironshanks own your words as well?

My tongue is my own! Some say I would do better at holding it. If I did I might not be in this spot o’ bother. Well, there’s no way around it now. I have the Tongue that Cannot Lie. And we live in an age where speaking the truth can get ye into a lot of bother. The powerful dinnae like their secrets being shared. And I have seen the spectral workings behind the world, the shadow games.

There I go again … anyhow, it was a gift, though I thought little of being given it at the time, from a certain fine lady I know. And therein hangs a tale … To repay your kindness – a fire to dry my feet by and a flask to sloken this thirst of many hard miles – and to pass the dour-watch afore daybreak, let me relate to you my tale.

I was once simply Thomas of Ercildoune. Do ye ken it? Near Melrose Abbey, on the road to Edinburgh town. Easy enough to pass through without even noticing it. Like many a braw lad I spent my day in daydreams and tomfoolery, a-wondering what my destiny would be. How could I escape the mundane lot of my kind – to toil in the fields for some laird, tug on my furlock, cap in hand, whenever he passed on his fine horse, and be grateful for the thin gruel our kind are meted out while some dine in luxury off the back of our sweat? It had broken my father, turned him sour. Ready with his fists, living for his thirst. Made my mother immune to her misery, hidden away inside hersel’.

I would not let it break me.

I took to wandering the hills thereabouts – to the Eildon hills to the south. Three distinct peaks, said to have been split by the wizard Michael Scot. You know he summoned a demon to do his bidding, but then couldnae get shot of it, so he set it impossible tasks: tae split the Eildons thrice, and to weave rope from the sands of the Tweed – and the beastie is still doing it to this day. Like me spinning my yarn, which will ne’er end, I hear ye grumble, if I keep digressing!

So, there I was, mooning about the Eildons. ’Twas a glorious summer’s day. You may not reck it now, on this foul Cailleach of a night, but Alba can be bonnie indeed. A break in the clouds and she’s the most beautiful lassie you’ve ever seen. Which leads me to the start of my tale!

I was idling beneath a May tree, letting the sun and shade dapple my face, imagining the kisses of some lassie appreciative of my neglected achievements, soothing the bruises of my pride, when I heard a horse’s hooves upon the lane, ringing bright and clear across the still hillside. I sat up and beheld a ferlie most comely.

Riding towards me was a queen – for her fine raiment and deportment suggested no less. She wore a dress the colour of rain-washed meadows, and rode a horse of the purest white. Its bridle glittered with silver, and from their jingling sound I fathomed they were bells. Their tinkling sent me into a kind of trance. Her fine, pale features were framed with a glory of coppery curls, which cascaded down her slender frame.

At first I thought she must be riding to meet some lord, but she turned her steed towards me. I quickly brushed myself down and bowed, low to the ground. I greeted her as the Queen of Heaven – flattery comes as easily to a poet as butter to a knife. We are born to praise the fairer sex. All that my father was not in his fist-talk, I was with my silk-words.

My lady declined such a high estimation of her rank. Perhaps she was as wise to smooth-tongue flatterers as I was to the wheedling of a cat looking for a saucer of milk. Instead, she revealed her rank and origin – which was even more astonishing. She was the Queen of Elphame, no less. You may find it hard to credit, but all I have experienced bears testimony to this truth, so I pray you to hear me out before you judge. Mind, I cannae tell a lie.

She told me she had come far from her homeland to visit me – yes even I found that hard to believe, but that was her purpose. For what reason? Well, who knows a woman’s motives? Their actions are as fathomless as Loch Ness. Kittle kattle they surely can be.

She told me to join her, up upon her white steed, and to accompany her back to Elphame. Well, when a beautiful woman asks you to join them for a bit of a gallop, you do not walk away if you have red blood in your veins. At the time all I thought was: any excuse to get closer to that comely frame. And so without a second thought to my safety, my hearth and my kin, I mounted up behind her. Oh, to put my arms around that slender waist was almost more than a man could bear, and to smell the sweet perfume of that coppery mane. If that wasn’t enough to put me into a swoon, then the jingling of her rein did the trick as she shook her bridle and off we set – and the bright Eildon hills became a blur as we passed beyond the Borders.

We wallopit down a green lane, which seemed to open up before us as we entered, the light and shade flickering by. I looked behind and the May tree I had sat by rapidly receded into the distance, a faint speck of light at the end of the telescoping tunnel of green.

What’s that? Oot o thocht, ye ken? All a bit far-fetched? By my guid dirk, I tell you it exactly as it happened. I can do no other. But if you found that hard to stomach, then you will not find palatable what is to follow. If it helps, then see it as a tale, a childish fancy to pass the dark hours. And, if truth be told, I can only understand it in that way – through the language of story. What I experienced … no words can do justice to, but I will do my best to stitch together a patchwork of my impressions, a crude equivalent of the glorious tapestry that unfolded afore me …

We rode on until it seemed the horse galloped across the night sky. A vast blackness engulfed us and an icy wind howled like the Cailleach’s breath itself. And to my horror, my fair queen fith-fathed afore me – her comely frame became a thin sack of bones, her mane greasy straggles, her smooth skin sunk into her cheeks, and her fulsome breast drooped low to her belly. I held a skeletal hag, draped in black rags! She turned around and I was confronted by her hideous visage.

‘Likes what you see, do you deary?’ she cackled, blasting me with her foetid breath and making me gag at the blackened, toothless maw.

I recoiled, but looking down at the chasm around me I realised I had no choice but to cling on. What had I done? I would pay the price for my foolhardiness.

Oh, Thomas, for once, why did you not leave the lassies alone?