Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

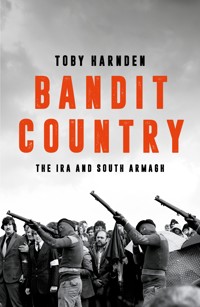

A NEW EDITION OF ONE OF THE MOST CELEBRATED BOOKS ON THE TROUBLES Branded as 'Bandit Country' by the British government, South Armagh was the heartland of the Provisional IRA. It was the rebel Irish stronghold where Thomas 'Slab' Murphy reigned supreme, bomb attacks on England were planned and the SAS tracked the IRA snipers who hunted British soldiers. In this acclaimed and remarkable book – originally published in 1999 – Toby Harnden, winner of the Orwell Prize, brings to bear his skills as a fearless journalist, inspired investigator and gifted historian, threatened with imprisonment for protecting his sources in Northern Ireland but undeterred. He draws on secret documents and unsparing interviews with key protagonists on both sides to produce perhaps the most compelling and essential account of the IRA and the Troubles.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 800

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

ii

iiiFor my parents, Keith and Valerie Harndeniv

Contents

vi

vii

Foreword

SUZANNE BREEN

Among the many hundreds of books written about the war in Ireland, Bandit Country is unquestionably a classic. When many journalists were content to accept the obfuscating pronouncements of Sinn Féin at face value or regurgitate spoon-fed British government press releases, Toby Harnden had the courage, tenacity and resourcefulness to go right to the heart of the IRA’s military struggle. It was remarkable that an Englishman relatively new to journalism was able to do this. But perhaps an outsider with a fresh perspective and tireless mind was exactly the right person to tell the story of the South Armagh Brigade, the Provisional IRA’s premier fighting unit.

In researching Bandit Country, Harnden was willing not just to ask the hard questions but to persist until he got the answers. He showed an uncanny ability to talk not only to RUC officers and British soldiers but to IRA members themselves. His ability to gain access to sensitive documents and records was the envy of the Irish press corps. Bandit Country is a forensic, granular account of what happened, written with a verve and immediacy that transports you there. x

It is clear that Harnden immersed himself in South Armagh, a place that too few journalists dared to explore. When most reporters were fixated on the republican leadership in Belfast and Derry, Harnden decided to speak to the IRA volunteers themselves and the British forces at war with them. There is a sense of history and a depth of analysis that few authors achieve. He was unsparing in his outlining of what that war entailed, leaving us with an indispensable record of how things really were. On many levels, Bandit Country almost performs the function of a truth and reconciliation commission.

Throughout his career, Harnden has been attracted to the dark underbelly of war. He went on to report from Iraq and Afghanistan and win the Orwell Prize for his book Dead Men Risen. He was able to persuade CIA officers to speak to him just as he did British soldiers, RUC officers and IRA members 25 years ago. He is a reporter of integrity who has risked imprisonment by protecting his sources. I have also been pursued through the courts for refusal to disclose my sources and know how difficult and lonely this road can be.

When Bandit Country was published, Harnden was criticised for damaging the ‘peace process’, as if it were essential for politicians to be allowed to airbrush the reality of death and destruction. Sinn Féin figures were alarmed at what he revealed about IRA activities. Unionists complained that he gave the IRA credit for its military effectiveness, rather than portraying volunteers as mindless thugs. British officials were aghast that details of the ‘dirty war’ had been made public. But Harnden was not writing for any political faction or interest group; he was writing for the people of Ireland, in xiwhose name the war was fought. Writing real contemporary history makes a lot of people uncomfortable. Evidence of collusion that Harnden collected was dismissed by the police on both sides of the border and by many journalists, who were perhaps embarrassed that they had not pursued this important story. Yet, the Smithwick Tribunal indicated that Harnden had been right all along.

Bandit Country is as relevant today as it was when first published. A number of the names in this book – and some who remain unnamed – are still operating in the borderlands of South Armagh and North Louth. It is essential reading.

Suzanne Breen

Belfast, 2024xii

Preface to the New Edition

When I completed the manuscript for BanditCountrysome 25 years ago, I told myself I would never return to South Armagh. I had named too many names and disclosed too much about the inner workings of the IRA’s military leadership. I had always intended to immerse myself in this place apart and write its definitive history without having to worry about my future personal security or having to work in Northern Ireland again. I moved to the United States shortly before publication in November 1999.

In some ways, I need not have worried. The reception to the book was extraordinary, and I received generous praise from some Irish republicans – though it was often privately communicated – as well as from former British soldiers, RUC officers, intelligence operatives and ordinary readers. Sales at Newry’s main bookshop, the closest to South Armagh, broke records. I sat in a storeroom signing copies – it was not considered prudent for me to be out there with the customers – as they flew off the shelves. It may be apocryphal, but I was told that some senior IRA figures would not put money in my pocket by buying the book so instead arranged for copies to be stolen.xiv

It was 15 years after publication when I broke my private vow and went back to South Armagh. I drove in a rental car, spoke to no one and did not linger. Some things had changed, but much hadn’t. The notorious Golf and Romeo watchtowers had come down, the army base at Bessbrook Mill – where I had once been locked in a room for a day with access to a dozen filing cabinets full of classified records – had closed, and there were no helicopters in the air. In Crossmaglen, Borucki sangar, named after a soldier killed in the town in 1976 and inside which four Grenadiers had nearly perished when it was set alight in 1992, was no more. The Royal Ulster Constabulary had been disbanded and replaced by the Police Service of Northern Ireland. But there were no police on the streets and scant evidence of the London or Belfast government’s writ extending this far south. Outside Murtagh’s bar, just off Crossmaglen’s main square, the strike mark from the .50 calibre bullet fired by Volunteer Micheál Caraher from a Barrett rifle, killing Guardsman Danny Blinco, was still carefully preserved. It was apparently a local point of pride.

Publication of BanditCountryled to greater scrutiny of the IRA in South Armagh and the unmasking of some of its prominent figures. I noted in 1999 that for legal reasons the pseudonyms ‘the Undertaker’ and ‘the Surgeon’ had been given to two of the most senior figures within the South Armagh Brigade. The Undertaker was Patsy O’Callaghan, who died of natural causes in a Drogheda hospital in 2021 at the age of 67. Although his obituary described him as an IRA volunteer, he had become disillusioned with the Provisional movement’s leadership and aligned with dissident IRA members who wanted to continue the armed struggle. After his xvdeath, former US Marine and one-time senior IRA man John Crawley described O’Callaghan as ‘a dynamic and daring resistance fighter who habitually led from the front’.

Two years after BanditCountrywas published, Seán Gerard Hughes, then aged 40, of Drumintee, South Armagh was accused of three counts of false accounting and eight counts of obtaining by deception. His lawyers stated that he ‘could not get a fair trial anywhere in Northern Ireland’ because my book had identified him as the Surgeon. In 2002, Hughes was named in the House of Commons under parliamentary privilege as an IRA leader. His properties were seized due to suspected fraud seven years later. In 2015, charges of IRA membership against Hughes were dropped. When BanditCountrywas first published, Hughes had been virtually unknown. After BanditCountry, Micheál Caraher’s brother Fergal, shot dead by Royal Marines in 1990 in an incident in which Micheál was wounded, was claimed by the IRA as a member. As my book detailed, for propaganda reasons Fergal had previously been identified only as a Sinn Féin member. When their father Peter John Caraher – whom I had interviewed – died in 2011, he too was identified as an IRA volunteer and described by a Sinn Féin MP as ‘one of the unsung heroes of the republican struggle’.

Like the gangster Al Capone, Thomas ‘Slab’ Murphy, the godfather of the IRA in South Armagh, was eventually convicted for tax evasion. He was sentenced to 18 months in prison in 2016. The IrishTimesnoted: ‘In 2006, long after the peace process was established, it took 400 British and Irish soldiers, PSNI and Garda officers and officials from the Criminal Assets Bureau and the British customs and excise to mount a raid on his farm complex of house, xvisheds, offices and oil tanks.’ On the loyalist side, William Frazer, the son of a UDR man killed by the IRA in 1975, died of cancer in 2019. During the research for BanditCountry, Frazer asked me to provide him with the names, addresses and workplaces of IRA members in South Armagh. I refused. Frazer later leaked historic documents to Ian Paisley, the Democratic Unionist Party leader, that detailed the names of innocent Catholics and connected them to the Kingsmill massacre of 1976, in which 10 Protestant workmen were killed. Paisley used parliamentary privilege to read out the names in the House of Commons. Two senior police officers separately told me that Frazer had supplied weapons to loyalist paramilitary organisations.

The passages in BanditCountryabout Irish police officers Garda X and Garda Y colluding with the IRA in the 1989 killings of Chief Superintendent Harry Breen and Superintendent Bob Buchanan – the most senior RUC officers to die in the Troubles – caused a firestorm. Senior Garda and RUC officers flew out to Washington D.C. to question me about the allegations, which I had laid out in painstaking detail. Ironically, my principal sources had been Garda and RUC officers, but it was clear that these trips were bureaucratic exercises in ticking boxes and finding nothing. Eventually, however, an inquiry was ordered by the Irish government. In 2013, after a £12.5 million investigation lasting eight years and testimony from 198 witnesses, the Smithwick Tribunal confirmed the allegations published in BanditCountrynearly 14 years earlier. Enda Kenny, the Irish Prime Minister, described the collusion as ‘absolutely shocking’, while Martin Callinan, the Garda commissioner, issued an unreserved apology for treachery that was ‘beyond xviicomprehension’. Garda X was retired Detective Sergeant Owen Corrigan, who died in Dundalk in February 2022. The Smithwick Tribunal concluded that Corrigan had passed information to the IRA. Corrigan had been in Dundalk Garda Station on the day Breen and Buchanan were killed.

The March 2024 interim report from Operation Kenova – the investigation into the activities of the IRA man and informer codenamed Stakeknife by his British Army handlers – concluded that on occasion the British authorities allowed murders to take place to protect its informers. Stakeknife was Fred Scappaticci, named in BanditCountryas a member of the IRA’s so-called ‘nutting squad’ – the unit that, ironically, was used to interrogate suspected informers. BanditCountryestablished that the IRA bombmaker Paddy Flood, whose body was dumped on the South Armagh border in July 1990 after being executed by the nutting squad, had not been an informer. In all likelihood, Flood was set up by the British to divert attention from a senior IRA man who was the real informer. Scappaticci died in April 2023. It is only now, a quarter-century after BanditCountrywas first published, that fuller details of the ‘dirty war’, an intrinsic element of the Troubles, are coming to light.

I had long known that BanditCountryhad been recommended by army units in Northern Ireland as required reading for British soldiers. The Smithwick Tribunal received an RUC document in which a detective chief inspector said BanditCountrycontained ‘perhaps hundreds of matters which could be the subject of police investigations and further inquiry’. What gratified me most, however, was a message I received the day after the Smithwick report xviiifrom a Garda officer who had served in Dundalk, telling me that 15 or so of his colleagues had ‘read my much-cherished copy’ of BanditCountry, which was being used as ‘a training tool’ for all new officers in the area.

An author’s duty to protect the identity of a source ends when that source dies. Sadly, that became the case when Lieutenant Colonel Rupert Thorneloe, the commanding officer of the Welsh Guards, was killed in action in Helmand, Afghanistan, in 2009. During my research for BanditCountry, Rupert, then a captain in the Welsh Guards, was an intelligence liaison officer with responsibility for South Armagh. His was essentially the same role as that of Captain Robert Nairac, who was abducted and killed in South Armagh in 1977. Rupert was an important source for BanditCountry, and our long discussions in pubs in Craigavon, during walks in Belfast and at his home in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, were invaluable in helping me develop the big picture. Rupert was humane, unconventional and fiercely intelligent, I lost a true friend when he died, and the British Army was almost certainly deprived of a future general. I wrote extensively about him in what became my second book, DeadMenRisen, about the British Army in Afghanistan, published in 2011. That ultimately led in 2021 to my third book, FirstCasualty, about the CIA response to 9/11. I owe Rupert a lot.

The IRA announced in 2005 that its armed campaign was over, but it did not disband, and disarmament was in secret largely symbolic. We can be sure that the IRA’s second Barret 90 sniper rifle was not among the weapons surrendered. In South Armagh, the IRA still exists and holds much sway. While the Good Friday xixAgreement of 1998 is still in effect, political progress is halting and the devolved Northern Ireland government dysfunctional. Sinn Féin, the IRA’s political wing, is now the largest political party in both Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic. The United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union in 2020 made the border between South Armagh and North Louth an economic reality once more, enhancing opportunities for smuggling and fueling demands for a united Ireland. While the IRA’s South Armagh Brigade is not currently active militarily, its leaders are the same rich and powerful men from 25 years ago you will read about in these pages. Their slogan remains ‘Tiocfaidh ár lá’ – ‘Our day will come’.

The original text of BanditCountryhas, I believe, stood the test of time and is republished here unchanged.

xx

Preface to the Original Edition

For the past three decades, South Armagh has exerted a powerful hold on the British and Irish imagination and my journey from teenage recollections of the death of Robert Nairac and the Narrow Water massacre to the completion of this book has been a long one. Many people have assisted me along the way and to all those who helped lay the foundations for this project and believed in it despite all the obstacles, I wish to express my profound gratitude.

My aim has been to go some way towards providing answers to a series of questions. Why is South Armagh such a place apart? What sort of people have joined the IRA and how do they live their lives? What has driven these men to the point where the end will justify any means? What has it been like for the outsider to be pitted against such men? Why has the South Armagh Brigade been consistently more effective than the IRA in any other area? What has been the human cost of this fight for Irish freedom? I have tried throughout to approach these issues by focusing on the thoughts, actions and experiences of the participants themselves, using their own words in preference to my own as often as possible. xxii

This is a contemporary history with all the freedoms and limitations which that entails. Detachment from a subject such as South Armagh is impossible and any belief that objectivity can be attained is flawed. But this is not intended to be a work for one side or the other. I have attempted to use language free from value judgements and I do not spare the reader the sometimes gruesome details of the events I deal with. If relatives of victims find some passages distressing, I hope they will understand that the goal of presenting as full a truth as possible would not have been served by attempting to airbrush distasteful realities. The main omissions are those necessary for legal reasons; most notably, the pseudonyms ‘the Surgeon’ and ‘the Undertaker’ have had to be given to two of the most senior figures within the South Armagh Brigade.

Belfast and Washington D.C.

April 2000

Prologue:Codeword Kerrygold

‘There’s a massive bomb beside South Quay station, Marsh Wall, Isle of Dogs, London,’ said the caller in a slow South Armagh brogue. His voice was calm and deliberate; it was not the first time he had delivered such a message. ‘Evacuate immediately. Codeword Kerrygold.’ Anne Brown, a switchboard operator at the IrishNewsin Belfast, felt her heartbeat quicken as she wrote down the words on the pad in front of her. Aware that a mistake on her part could lead to the deaths of scores of people, she requested that the caller repeat the details. ‘Was the codeword Kerrygold?’ she asked. ‘Same as the butter,’ he answered and hung up.

In the decade she had worked at the newspaper, Mrs Brown had dealt with dozens of coded warnings but this was one she had never expected to hear. It was 5.54 p.m. on Friday 9 February 1996 and just over 17 months earlier the IRA had declared a ceasefire; like many in Northern Ireland, she had believed that the Troubles were over.

At 5.28 p.m., another man had dictated a statement from the IRA’s Army Council to John Murray, a reporter with RTÉ, the Irish Republic’s state broadcasting corporation. ‘It is with great reluctance that the leadership announces that the complete cessation xxivof military operations will end at six o’clock on February 9th,’ the statement said. ‘The cessation presented a historic challenge for everyone and Óglaigh na hÉireann [the IRA] commends the leadership of nationalist Ireland at home and abroad. They rose to the challenge. The British Prime Minister did not. Instead of embracing the peace process, the British government acted in bad faith, with Mr Major and the Unionist leaders squandering this unprecedented opportunity to resolve the conflict.’ The statement was signed ‘P. O’Neill’, the nomdeguerreunder which the Provisionals had issued warnings and claimed responsibility for attacks over the previous 25 years.

On both sides of the Irish Sea, few could bring themselves to believe that the statement or the warnings were genuine. When RTÉ’s main evening news began at 6.01 p.m., there was no mention of the IRA announcement. Fifteen minutes later, an officer from Scotland Yard telephoned the Irish News to ask Anne Brown to go through once more what the South Armagh caller had told her. John Bruton, the Irish premier, went ahead with a 6.30 p.m. engagement at a Dublin art gallery while his aides made desperate attempts to reach Sinn Féin officials. Commander John Grieve, head of the Metropolitan Police’s anti-terrorist branch, later admitted that when he was paged by detectives with a message to call Sir Paul Condon, the Met’s Commissioner, he thought it must be a practical joke.

Four officers had initially been despatched from Limehouse station shortly after 6 p.m. to close the Docklands Light Railway station at South Quay. But there was confusion about exactly where the IRA had said the bomb was and over the next hour another 16 officers were sent out to set up cordons and clear the xxvstreets. Some buildings were evacuated only for their occupants to be sent back ten minutes later; others very close to South Quay station knew nothing about the bomb warnings. At 6.48 p.m., PC Roger Degraff and another officer spotted a blue car transporter parked outside South Quay Plaza between two office blocks and next to a row of shops.

Inside the transporter was more than 3,000 lbs of explosives made up of ammonium nitrate fertiliser mixed with icing sugar in plastic sacks. The sacks were in two compartments in the back of the transporter and packed around ‘booster tubes’. Designed to increase the power of the blast, the tubes had been made from parts of scaffolding poles drilled with holes and stuffed with 10 lbs of Semtex high explosive. Attached to the booster tubes were lengths of improvised detonating cord made from plastic tubing filled with PETN and RDX, the two constituent elements of Semtex. The bomb was to be set off by a nail attached to a kitchen timer which would complete an electrical circuit, sending power through to two detonators which would activate the detonating cord and, in turn, set off the booster tubes and trigger the main explosive charge. Shortly after the bomb lorry was parked, a ‘memo park’ timer, invented for absent-minded motorists who needed prompting that their meters were about to run out, had been used to ‘arm’ a mercury tilt switch anti-handling device. The kitchen timer had been set for two hours so that it would run out at 7 p.m.

The two policemen walked around the lorry and quickly concluded that if the IRA warnings were genuine, the bomb was probably inside the vehicle. Degraff went to the cab and was about to look inside when he stopped himself. Had he opened the door, xxvihe would have set off the anti-handling device and activated the bomb. Realising he needed to clear the row of shops next to the transporter, Degraff rushed into a newsagent’s store at 6.56 p.m. and told Inan Bashir and his assistant, John Jefferies, to leave immediately. Bashir, who had been at work at the family business since 5 a.m., said he would first shut up the shop while a sceptical Jefferies observed: ‘We are in a ceasefire.’

A minute before 7 p.m., a blue flash could be seen several miles away as the bomb exploded; Bashir and Jefferies were blown through two walls and their bodies buried by tons of rubble. Degraff, 30 yards from the device, felt a deep rumble and a rush of wind as he was blown off his feet. For a fraction of a second, the hundreds of people still working in Canary Wharf, one of Europe’s tallest tower blocks, felt that the building was about to collapse. ‘I was lying curled up in a ball listening to glass and debris falling from all the buildings,’ Degraff said afterwards. ‘I lay there for a while, waiting for something big to fall on me.’ Barbara Osei, 23, who had been cleaning offices with her brother Isaac, was sprayed with hundreds of tiny slivers of glass; she was blinded in one eye and her face, arms and hands were so badly cut she needed 300 stitches. Members of the Berrezag family, Moroccans who worked as cleaners at the Midland Bank branch in South Quay, were even closer to the blast. Their car was virtually destroyed as they sat in it; Zaoui Berrezag, 51, suffered severe head injuries and never fully recovered his memory. Graeme Brown, an advertising designer, was knocked out; he woke a few minutes later surrounded by the water from a burst main. ‘It was bizarre,’ he said the next day. ‘I knew it wasn’t a bomb, because we don’t get them in London any more, do we?’xxvii

Soon, Docklands was echoing to the sound of police and ambulance sirens, wailing alarms and breaking glass as the residents of council flats knocked their shattered windows out into the streets below. Debris had been spread over a radius of 300 yards; where the transporter had been, there was a crater 32 ft wide and 10 ft deep. The blast had caused an estimated £150 million of damage to property. Its impact was felt world-wide, with television bulletins across the globe leading with the news. The IRA had struck another blow at the heart of the British establishment less than three years after devastating the City of London for the second time in 12 months. As the home of merchant banks, television and advertising companies and, in Canary Wharf, the Mirrorand Telegraphnewspaper groups, Docklands was an ideal prestige target.

While political argument raged during the next few days, two funerals went almost unnoticed. The traditional Islamic colours of gold and green were draped over Inan Bashir’s coffin as it was driven from his home in Streatham to Croydon mosque for a private service. His elderly father Shere, who had to be supported by his second son as he went into the mosque, was to die within a year. John Jefferies’ father, a widower, was nearly beside himself with grief at the loss of his only son, who had still lived with him. White chrysanthemums had been arranged into guitar-shaped bouquets as a tribute to the amateur musician who had often busked at Underground stations. As the mourners gathered at Lewisham crematorium in south London, they listened in silence to a tape of Jefferies’ own rendition of a song he had written and recorded for a new girlfriend just a few days before the bomb. He had called it GladtobeAlive. xxviii

Chapter 1

The Boss

‘From Carrickmacross to Crossmaglen, the polisman he did vow There are more rogues than honest men and anyone will allow’

(The Dealin’ Men of Crossmaglen, traditional ballad, C 1900)

‘If there is ever a big meeting and they are all there and a target is given, then the Crossmaglen boys are on their way to do the job as soon as they get out of the door.’

(South Armagh informer, Military Intelligence Report, 1975)

Inside a cattle shed five miles west of the Ring of Gullion and 200 yards beyond the border into the Irish Republic, nine men worked silently and methodically as the light faded into the late afternoon gloom of a cold January day in 1996. Some were farmhands; others made a living doing odd jobs or driving lorries and tractors around the South Armagh borderlands. Most had been involved in smuggling for many years, profiting from the hated line that had divided Ireland for three quarters of a century by moving contraband to and fro across the United Kingdom’s only 2land boundary. Led by ‘the Surgeon’, the notorious commander of the South Armagh Brigade, they were among the most trusted volunteers in the IRA’s heartland; between them, they had been involved in several hundred attacks on the security forces. But this job was different, and each man knew the significance of what he was there to do.

Micheál Caraher, an IRA sniper responsible for the deaths of up to eight soldiers and policemen, was there. So too were Séamus McArdle and Bernard McGinn, key members of the back-up team used to get Caraher in place and protect him as he fired a single .50 (half-inch) calibre bullet from a high-powered American sniper rifle. Frank ‘One Shot’ McCabe, one of the senior figures behind the sniper attacks, was also in the shed; an eight-year sentence for possession of explosives and a firearm had not dulled his desire to see Ireland united. A man who had earned his reputation as an IRA volunteer in a unit which shot soldiers and bombed Army bases on the Continent worked alongside his elder brother. Each man had been told by either the Surgeon, a thick-set man with piercing blue eyes, or Michael ‘Micksey’ Martin to rendezvous that morning at the galvanised iron shed, situated at the end of a long lane near Donagh’s crossroads and close to the Drumlougher border crossing between South Armagh and County Monaghan. Once gathered, they had been given the word from ‘the Boss’ that South Armagh had been entrusted with the task of making, transporting and detonating a huge bomb. A bomb for England.

At one end of the cattle shed was a stack of sacks, each containing a hundredweight of ammonium nitrate agricultural fertiliser. As one man split the sacks, the others shovelled the contents into 3an electric barley crusher plugged into the power shaft of a tractor. The barley crusher, designed to break down animal feed, was used to grind the granules of fertiliser into tiny particles. Once each lot of fertiliser was of the requisite consistency, several bags of icing sugar were added and the two ingredients were stirred together to make a light brown substance. The side panels had been removed from the back of a lorry converted into a car transporter, revealing a hidden compartment. The compartment, lined with plastic sheeting, was then packed with three tons of explosives. After the job had been completed, the barley crusher was washed and then towed away behind the tractor by Caraher. The Surgeon took charge of the car transporter with the explosives inside; a red Peugeot 205 ‘scout car’ drove ahead to check the roads were clear. The next day, the shed would revert to being a cattle byre; all that had been required to transform it into a temporary bomb factory had been a friendly farmer and a watertight roof.

According to Detective Inspector Alan Mains, the RUC officer who led the Docklands inquiry in Northern Ireland, the plan to blow up South Quay had been drawn up at least six weeks before the bomb was mixed. On 30 November 1995, President Clinton had told a cheering crowd gathered outside the City Hall in Belfast: ‘You must say to those who still would use violence for political objectives: you are the past; your day is over.’ It was a neat rejection of the IRA’s slogan ‘Tiocfaidh ár Lá’, Irish for ‘Our Day will Come’, which had often been accompanied by a clenched fist salute as it was shouted from the dock. But even as Clinton was speaking, work was already in progress in South Armagh and across the border in North Louth to construct the car transporter 4that would be loaded with the Docklands bomb. Nowhere else in Ireland was the commitment to the IRA’s armed struggle so strong. From the day the IRA ceasefire had been declared in August 1994, there had been extreme scepticism in South Armagh about the ‘peace strategy’ of Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness, the Sinn Féin leaders; sometimes this bordered on open contempt. South Armagh volunteers had heard the clever words of British prime ministers and American presidents before and set little store by them.

The very mention of South Armagh can send a shiver down the spine of any one of the tens of thousands of soldiers who have served there since the Troubles began. Branded ‘Bandit Country’ in 1975 by Merlyn Rees, then Northern Ireland Secretary, no other part of the world has been as dangerous for someone wearing the uniform of the British Army. Some 123 soldiers have been killed in the South Armagh area since August 1971, around a fifth of all military casualties in Northern Ireland, along with 42 Royal Ulster Constabulary officers and 75 civilians. According to RUC statistics, the area within a 10-mile radius of the heart of South Armagh has seen 1,255 bomb attacks and 1, 158 shooting incidents since the Troubles began.

Situated in one of the six counties of Ulster which make up Northern Ireland, South Armagh is around 192 square miles in area and home to approximately 23,000 people. As defined by both the British Army and the IRA, it is enclosed to the east by the A1, the main Belfast-to-Dublin road, to the south and west by the border with the Irish Republic and to the north by an imaginary east-west line running through Mountnorris and Keady. The population of South Armagh is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, almost 5exclusively so in the land south of the A25 road. It has been in this 120-square-mile southern portion of South Armagh, including the town of Crossmaglen and the villages of Cullyhanna, Forkhill, Drumintee and Jonesborough, that the overwhelming number of Army and RUC casualties has occurred.

History and landscape are rooted deep in the psyche of the people of South Armagh. At the centre of both sits Slieve Gullion, whose bulk looms through the mist high above the watchtowers, fields and blackthorn hedges like a slumbering giant keeping guard over South Armagh and Ulster’s ancient frontier. At the base of the mountain, the granite peaks of the ring dyke stand sentinel as if protecting their master through the ages. On six of the peaks stand the modern watchtowers, the latest in a long line of military fortifications built by the invader in the vain hope of subjugating the natives of a countryside in which the outsider has never been welcomed. When the mist clears, eight counties can be seen from Slieve Gullion’s summit, 1,840 ft above sea level.

For the British soldier, Crossmaglen – known as XMG to the military, and Cross to locals – is a place of hostility, isolation and the constant threat of death. Before going out on patrol, troops are briefed that every gorse bush, stone wall or ditch, every cowshed, milk churn or bale of hay could hide a bomb; if a sniper decided to strike, the victim would probably never even hear the crack of the bullet being fired. In the Square in Crossmaglen, site of a thriving market each month and the place where eight soldiers have met their deaths in the past quarter century, an IRA memorial has been erected. The inscription reads: ‘Glory to you all praised and humble heroes who have willingly suffered for your unselfish 6and passionate love of Irish freedom.’ Just eight miles north of Crossmaglen is Newtownhamilton, where a substantial number of Protestants live; soldiers consider it the ‘softest’ posting in South Armagh and some joke that the acronym NTH stands for ‘No Terrorists Here’.

Captain Nick Lewis said of his time in South Armagh with the Coldstream Guards in 1996:

Conditions at Crossmaglen and Forkhill had to be experienced to be believed. In terms of space and light, the mortar proofing made it a bit like being in a submarine. In Crossmaglen there were more men than beds and no windows. You were banned from being outside or sitting in the sun because of the mortar and sniper threat. Outside in the baronial fiefdom of South Armagh, IRA members operated, intimidated and plotted and went about their daily business of farming, smuggling and drinking. It made us wonder just whose freedom was being constrained.

The sense of helplessness, frustration and incomprehension felt by the ordinary soldier had changed little in the 20 years since Captain Tony Clarke, of the Parachute Regiment, had recalled the experience of serving in Crossmaglen in his memoir Contact. He wrote:

I get the feeling of being one of those shooting-gallery targets that go round on a conveyor-belt, endlessly waiting for someone to knock it down. South Armagh, still light-years away from 7civilisation, still living in the dark ages, where barbarity and cruelty are the prime factors of a successful life. Where stealing and killing are as natural a part of living as breathing is to most of us.

For republicans, Crossmaglen is their stronghold, the capital of the de facto independent republic of South Armagh.

Proximity to the border, the absence of a Protestant community, the undulating terrain and the powerful sense of rebellion throughout history have all combined to make South Armagh the ideal operating ground for the IRA. Hostility towards authority stretches back to the Middle Ages and smuggling became widespread as soon as the border was drawn up. Moving goods across the border under cover of night and concealing illicit merchandise in vehicles while keeping one step ahead of the law became skills as useful to the IRA man as to the smuggler. Modern-day republicanism in South Armagh is simply the latest manifestation of its independence and refusal to submit to the Queen’s Writ or any other rule from beyond its hinterland.

Constables Sam Donaldson and Roy Millar, who were blown up in August 1970 by a car bomb left outside Crossmaglen, were the first RUC men to be killed by the IRA during the modern Troubles. But for centuries enforcers of the law had been meeting their end in South Armagh. The security forces were soon to find that IRA members were often interchangeable with those for whom defiance of authority was already a way of life. Before the Troubles began, a small-time South Armagh smuggler was fined and ordered to pay compensation at Forkhill Petty Sessions Court after admitting stealing farm animals in Northern Ireland and 8selling them at Dundalk market. By the 1990s, the same man was a major criminal with an annual turnover of hundreds of thousands of pounds; he was also an IRA volunteer playing a central role in mounting bomb attacks in the City of London. In the intervening years, Sergeant Albert White, who had investigated the theft of the farm animals, had been shot dead by the Provisionals in Newry and the courthouse in Forkhill had been destroyed by a bomb.

Since the early 1970s, South Armagh has effectively been under the control of the IRA. Road signs warn not of children crossing but of a Sniper at Work, the red triangle framing the silhouette of a masked gunman waving an Armalite. A few miles from the barn where the South Quay bomb was mixed, a mock advertisement declares: ‘Richardson’s Fertiliser. Tried and tested at home and abroad by P.I.R.A.’

The Army presence in South Armagh is centred around its headquarters at Bessbrook Mill, a 19th-century linen factory situated in a Quaker model village whose founder, John Grubb Richardson, laid down that there be no pawnshop or pub within its boundaries. Bessbrook was named by John Pollock, an 18thcentury linen manufacturer, after his wife Elizabeth or ‘Bess’ and Camlough river or ‘brook’. In the grounds of the converted mill is one of the busiest helipads in Europe and a garden of remembrance peppered with Mourne granite memorials to the soldiers who have been killed in South Armagh. The commanding officer there controls the three joint RUC-Army bases at Crossmaglen, Forkhill and Newtownhamilton; village police stations in 1971, they are now mini-fortresses strengthened at a cost of millions of pounds to withstand mortar and bomb attack. 9

Since the mid-1970s virtually all military movement has been by helicopter to avoid casualties from landmines planted under the roads; even the rubbish from the security force bases is taken away by air. As the threat of surface-to-air missiles and heavy machine-guns has increased, helicopters have flown in twos and later threes for mutual protection. Even in the early 1990s, the IRA would set up illegal roadblocks to demonstrate its invulnerability. The border between South Armagh and North Louth has become the traditional dumping ground for the bodies of men executed by the IRA after confessing to the capital offence of being an informer. In August 1998, the Omagh bomb, which killed 29 people, was put together in South Armagh by Provisionals who had defected to the so-called ‘Real IRA’.

South Armagh’s strategic position on the border and the formidable strength of armed republicanism there have meant that it has long been the place where new weapons and prototype bombs have been tested after being produced by the IRA’s Dublin-based engineering department. The South Armagh Brigade has pioneered the use of mortars with eight of the 11 new types manufactured since 1974 being first fired by the Crossmaglen IRA unit. Semtex was first used by the IRA in South Armagh and radio-controlled bombs were developed there. Bicycles, torches, Irish tricolours and the bodies of informers have all been elaborately booby-trapped with bombs. In August 1993, a tractor was loaded with explosives and a dummy placed in the driver’s seat before it was guided by radio control into the village of Belleek. Five years later, a Real IRA member from South Armagh perfected a bomb that could be detonated by calling a mobile phone. 10

Within the IRA, the South Armagh Brigade has always enjoyed a degree of autonomy. During the organisation’s ceasefire of 1975, the South Armagh Brigade carried on killing; after the 1994 ceasefire, Frank Kerr, a Post Office worker, was shot dead by South Armagh volunteers during an IRA robbery in Newry.

IRA leaders in South Armagh have gone to extraordinary lengths to ensure their men would escape capture and imprisonment. On 9 May 1992, Mark Flynn, a young volunteer from Silverbridge, was preparing a 180 lb bomb in a derelict house on the Tullymacrieve Road in Mullaghbawn. The device was to be activated by the light from a flash bulb; designed to be placed in a wheelie bin and to kill soldiers on foot patrol, it represented a significant advance in IRA bomb technology and had therefore been fitted with a self-destruct charge that would destroy forensic evidence. As Flynn moved the bomb, this charge exploded, blowing off his right thumb and two fingers, burning his upper body and face and blinding him. He was rushed across the border to hospital by his companions, Joe McCreesh and Paddy Murphy, both IRA men in their early twenties. The following morning, McCreesh and Murphy were arrested in a hijacked car that contained a balaclava and fragments of bloodstained wood. After the security forces sealed off the area, a forensic scientist was flown in by helicopter to examine the derelict house. She was able to reconstruct a wooden A-frame in the house and take samples that matched exactly the fragments of wood found in the hijacked car, thereby establishing an evidential link between the three young IRA men and the bomb.

On 23 September 1992, four months after Flynn had been blinded, the South Armagh Brigade hijacked a van near Newry, packed 11it with 3,500 lbs of explosives, drove it to Belfast and abandoned it outside the Forensic Science Laboratory in Newtownbreda. At 8.45 p.m., 40 minutes after a coded warning had been issued, the device exploded, almost demolishing the laboratory and damaging 1,002 homes in the area, most of them on the loyalist Belvoir estate. The blast was felt up to 12 miles away and the bomb was later assessed as probably the biggest ever to be detonated in Northern Ireland. In the event, the wood samples which incriminated Flynn, McCreesh and Murphy had been safely locked away in a vault and were not damaged in the blast. Flynn was so badly injured that charges were not proceeded with while McCreesh and Murphy were both convicted of attempting to remove evidence linked to the premature explosion in Mullaghbawn.

The South Armagh Brigade’s efficiency, militancy and independence made it the obvious choice to be entrusted with bringing about the end of the ceasefire in February 1996. Having been given the job, the South Armagh men set about their task with skill and some relish. Starting with a Ford Cargo lorry once owned by British Gas and parts cannibalised from two other lorries, a new vehicle was constructed by a team of IRA associates skilled at cutting and welding. The end result was a blue vehicle that looked like an ordinary car transporter. In fact, it was the outer casing of a mobile bomb, the platform at the back concealing a void into which the explosives would be crammed. At the McKinley farm in Mullaghbawn, ramps were made so that a trailer could be loaded onto the back of the transporter to make it look as if it was carrying an ordinary load. Bits of aluminium used in making one of the ramps were later found on a Mitsubishi flatbed lorry owned by 1232-year-old Patrick McKinley. Commander John Grieve, head of SO13, the Met’s anti-terrorist unit, later speculated that the inspiration for the design of the bomb lorry might have come from a film. ‘It’s always been one of my thoughts,’ he said, ‘after seeing Gene Hackman in The French Connection during my childhood, that that’s where they got the idea of burying the bomb right down deep in the bodywork.’

The IRA was as meticulous about planning the movement of the bomb from South Armagh to South Quay as it had been in constructing the car transporter. Never before had an IRA vehicle bomb been fully assembled in Ireland and driven to its destination in England without using any of the ‘sleeper’ units or the logistical support network in place. Once the vehicle had been built, a ‘dummy run’ to London was carried out to help the IRA volunteer selected to drive the bomb familiarise himself with the motorway system and the routine at the ferry ports. The dummy run was also a way of testing out anti-terrorist procedures; the IRA was well aware that during the ceasefire the authorities had let their guard drop in a number of areas. A reconnaissance of the Docklands area had already been carried out by two South Armagh volunteers who had confirmed that vehicles were not being checked on the way in or out of Docklands.

Even before the ceasefire, South Quay had been identified by the South Armagh Brigade as a suitable target. Since 1991, the IRA leaders in the area had been the driving force behind the ‘England campaign’ and had proved spectacularly successful. In April 1992, a massive bomb at the Baltic Exchange in the City of London had killed three, injured 91 and delivered a devastating blow to the 13financial heart of the United Kingdom. A year later, the City had again been the target when two men drove 2,200 lbs of homemade explosives into Bishopsgate. The blast killed a newspaper photographer and caused damage estimated at more than £500 million.

Séamus McArdle, from Silverbridge, was chosen by the Boss to drive the transporter to South Quay. Aged 27, he had more than 10 years as an IRA volunteer behind him but had never been arrested in Northern Ireland; he was viewed as a ‘clean skin’ whose fingerprints had not been taken by the RUC and whose absence from South Armagh would not attract suspicion.

On Monday 15 January 1996, McArdle picked up final instructions from the Boss and collected the transporter, which had a trailer loaded on the back, from a farm in North Louth. He then drove it 50 miles to Belfast ferry terminal and onto the 7 p.m. Stena Sealink ferry to Stranraer on the west coast of Scotland. As he did so, McArdle noted that there was no weighbridge in use to check for abnormally heavy loads. This time, the secret compartments within the transporter were empty; on his next journey they would be filled with explosives. After arriving at Stranraer at 9.30 p.m., McArdle drove the transporter to the BP truck stop at Carlisle where he met another South Armagh volunteer. They booked into rooms 14 and 16 under the name Murphy and stayed the night there.

The next day, the pair went to Carlisle Car Auctions and bought a Renault 25 and a Peugeot 205. They drew attention to themselves by paying £600 for the Renault, which was well over the odds, and the difficulties they had loading it onto the transporter without using ramps. After the auction, the two parted company. 14McArdle drove the transporter back to South Armagh via Stranraer and Belfast while the other volunteer returned in the Peugeot via Holyhead and Dun Laoghaire. That night, the transporter, with the Renault on the back, was parked outside Caesar’s night-club near Jonesborough, just a few yards south of the border on the A1.

Once the bomb had been mixed and packed into the transporter, everything was in place for the Docklands attack. On Wednesday 7 February, McArdle picked up the transporter and trailer from the border farm and travelled the same route as he had on the dummy run, catching the 7 p.m. ferry from Belfast and staying at the Carlisle truck stop. He also linked up with a scout car which was to accompany him to London. McArdle booked in as ‘Mr Hoey’, the name of a prominent South Armagh volunteer. For both the dummy and the bomb runs, the transporter had been fitted with false numberplates bearing the registration 575 7IB, which had been taken from a car transporter broken up for scrap in Cullaville, two miles from Crossmaglen. As a precaution against the vehicle being traced later, McArdle booked the transporter in at the truck stop using the registration 575 7BI.

On the Thursday morning, McArdle continued his journey south down the M6, stopping at the Hollies service station in Staffordshire and then at a truck stop on the M25 at South Mimms in Hertfordshire. At this stage, McArdle was joined by another South Armagh volunteer and they spent the night nearby. They rose early on Friday 9 February, the day of the blast, and drove through the Dartford Tunnel to a piece of waste ground on an industrial estate at River Road in Barking, arriving in the early afternoon. The pair were then taken in the scout car to eat at a nearby café and prepare 15themselves for the final and most hazardous part of the IRA operation – the 11-mile journey to South Quay.

While at Barking, the 575 7IB numberplates, which identified it as an Irish vehicle, were substituted with English plates bearing the registration C292 GWG; the plates were later found to have been made at a repair garage in Crossmaglen. The transporter was now what was known in the anti-terrorism world as a ‘ringer vehicle’. A similar transporter owned by a man in Tandragee in North Armagh had the genuine registration C292 GWG; an IRA supporter had stolen its licence disc during the first two weeks of January. This meant that if the bomb transporter’s registration was run through a police computer it would appear to be the Tandragee vehicle. McArdle and his colleague then unloaded the trailer from the back of the transporter and primed the device by linking the timing and power unit (TPU) in the cab to the bomb compartment at the back. At about 4.15 p.m., the transporter, driven by McArdle, and scout car left River Road and travelled down the A13. Security camera footage at South Quay showed the lorry arriving at 5.04 p.m. and the two IRA men getting out of the cab. Before they did so, McArdle checked that the TPU, a wooden box containing timers and wires, was set correctly; a red warning light would have come on had there been a problem. He then removed a wooden dowel pin from the side of the TPU and flicked a switch; the bomb was now ‘armed’ and the two-hour kitchen timer ticking away.

Although in most respects the Docklands bomb had been a classically successful South Armagh operation, a few tiny clues were to lead to Séamus McArdle’s eventual conviction. After appeals for information, more than 850 people telephoned the Met’s 16anti-terrorist hotline. The 199th caller to be logged was Arthur Ward, a lorry driver who reported having seen an unfamiliar car transporter and trailer parked at River Road on the day of the explosion. He had stopped, he later told Woolwich Crown Court, because ‘I am nosy’. Officers picked up every scrap of urban detritus they could find on the River Road site. The search provided the key to the inquiry, named Operation Heron by the Met. Inside an old tyre were found a copy of Truck and Driver magazine, receipts for a parking ticket at South Mimms and a packet of Screenies windscreen wipes, and a lorry tachograph sheet. There were broken pieces of a 575 7IB numberplate nearby. The trailer was also there; particles of PETN explosives and paint scrapings eventually led to it being linked to the transporter and traced back to South Armagh. Police believed that the presence of a British Telecom engineer working up a nearby telegraph pole had panicked the IRA men into thinking they could be under surveillance and deciding not to burn the tyre and its contents.

For 14 months, police did not know who had driven the bomb to South Quay, although three thumbprints from the same person had been found on the Truck and Driver magazine, an ashtray at the Carlisle truck stop and a ferry ticket stub handed in at Stranraer on the return leg of the dummy run. In April 1997, the RUC took the fingerprints of Micheál Caraher, McArdle and two other members of an IRA sniper team captured in South Armagh by the SAS. A match was made between McArdle’s thumbprints and those sent over by the Met; ‘triple thumbprint man’ had been identified.

The Renault and Peugeot cars had been located at the McKinley farm, and on 7 June 1996 Patrick McKinley had been arrested 17during a massive security swoop codenamed Operation Fisherton. Both McKinley and McArdle faced trial on charges of conspiring to cause an explosion while McArdle was also charged with murdering Inan Bashir and John Jefferies. At their joint trial, which began at the Old Bailey in January 1998, it was established that the two cars bought in Carlisle had ended up at the McKinley farm within 48 hours. Ramps on the trailer found at River Road were almost identical to those on the Mitsubishi lorry he had rebuilt. McKinley’s defence was that the cars had been sold to him by Patrick Goodfellow, a Bessbrook man with IRA links who had hanged himself from a beam in his roof space two weeks before Operation Fisherton. The judge directed that he be acquitted.

Also arrested during the Docklands investigation was Kevin ‘Fred’ Loye, a barman from Mullaghbawn. Loye was known to be a republican and a friend of Micksey Martin, one of the four most senior IRA men in the South Armagh Brigade. In April 1994, Martin, at that time wanted for gunrunning offences in America, and Loye were arrested after a high-speed car chase that ended in Ballsmill in South Armagh. When the security forces opened fire, Martin crashed his car and was wounded in the right thigh; Loye remained silent during five days of questioning and claimed through his solicitor that he had been thumbing a lift. Loye was arrested again in June 1996 after one of the six coded warnings about the Docklands bomb was traced to a telephone box in Drogheda in County Louth. The box was removed and several of Loye’s fingerprints found on it; he again refused to answer any questions and was released without charge.

McArdle’s defence at the Old Bailey was ingenious. He told the 18jury he spent 10 or 15 days a year working for a powerful South Armagh farmer known as ‘the Boss’. Some of the work would be legal, feeding cattle or transporting hay, but some of it would involve smuggling diesel or kegs of beer across the border. He knew that the Boss was a senior IRA man and admitted running messages for him that probably had something to do with the IRA. Faced with fingerprint evidence that linked him to both the dummy and the bomb runs, McArdle said that he had been asked by the Boss in January to do a job for him that involved bringing back cars from England. This he had done and when he arrived in Carlisle for a second job in February the Boss had told him that the job ‘was going to be different this time’ and asked him to drive the transporter further south. McArdle said he had handed the transporter over to another driver at South Mimms and hitched a lift home. He knew nothing about the bomb and assumed the Boss had used him because ‘he trusted me in the past and his own customers through smuggling and that, so he probably would have knew I’d keep it to myself’.

McArdle told the Old Bailey that he could not identify the Boss because of possible reprisals. ‘I can’t scream because I would be putting myself in danger and my family in danger,’ he said. But questioning by the judge elicited that the Boss owned a farm and dealt in cars, lived six or seven miles from Dundalk, was aged between 45 and 50 and was balding. At least one member of the Old Bailey jury believed McArdle’s story and, with the jury unable to reach a unanimous verdict, a retrial was ordered. Following a second trial at Woolwich Crown Court in May 1998, McArdle was convicted of conspiring to cause an explosion and sentenced to 1925 years’ imprisonment. As he left the dock, his supporters from South Armagh cheered and waved two fingers to signify that he would serve less than two years in jail before being released under the Good Friday Agreement which Sinn Féin had endorsed the previous month.

Although he had lied about the extent of his role in the Docklands bomb, it seems McArdle had largely stuck to the truth about the man who was behind the IRA operation as a guard against being caught out in cross-examination. During the two trials, he gave enough details about the Boss to leave few doubts among the initiated about the man he was referring to.

The Boss had been the central IRA figure in South Armagh for more than 25 years and, by the time of McArdle’s trial, was also the IRA’s Chief of Staff, the leader of the world’s most feared paramilitary organisation. His importance had only begun to be revealed publicly 13 years earlier when an armour-plated Ford Cortina carrying four RUC officers was blown apart at Killeen as it escorted a lorry carrying a Brinks Mat gold bullion consignment across the border in May 1985. All four were killed when a 900 lb radio-controlled bomb packed into an articulated trailer on the hard shoulder was detonated. Afterwards, Sir John Hermon, then RUC Chief Constable, joined a line of his officers who had spread out across a field next to the main Belfast-to-Dublin road for the grim task of gathering the remains of their colleagues. As the line advanced slowly, one officer knelt down and picked up a severed hand. ‘Fingerprint bag, please,’ he called. Another RUC man said: ‘I know that hand, it belongs to Tracy Doak.’ It was a left hand and, although the little and ring fingers were missing, he 20had recognised a gold band on the middle finger. The ring finger, on which a diamond engagement ring had been worn, was never found. Constable Tracy Doak, 21, the driver of the Cortina, had been due to marry a fellow police officer that year.

At her funeral at Ballywatt Presbyterian Church near Coleraine in County Derry, the Reverend Ian Hunter told the congregation that Constable Doak had been murdered, like so many others, ‘by an unseen enemy and faceless men who do their deeds in secret and in hiding’. But Hermon, who was becoming increasingly depressed about the number of RUC losses in South Armagh and Newry, knew exactly who the unseen enemy was. Shaken by what he had seen at Killeen, Hermon decided to let the IRA know that its hierarchy in South Armagh was being watched and revealed during a radio interview that a ‘wealthy pig smuggler’ living in the Irish Republic had been responsible for the Killeen attack.