Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

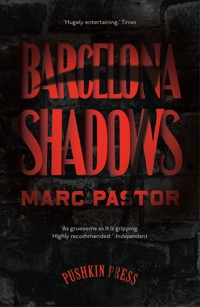

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Children are going missing in Barcelona. A body is found, twisted, drained of blood. The locals say a devil is moving in the shadows, spiriting away the innocent.To the police, it just means more corpses in a city where death is a daily occurrence. Who cares about the children of a few prostitutes and thieves?Inspector Moisès Corvo-jaded, dissolute, yet with an uncanny sixth sense-knows something is different this time. To discover the true identity of the "monster" he must journey through Barcelona's underworld, from high-class brothels to lurid casinos, where there are powerful people who will do anything to stop him. He cannot imagine the horror that awaits him.Visceral and shocking, Barcelona Shadows opens up the heart of evil, in a macabre world where the lines between life and death are blurred.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 358

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MARC PASTOR

BARCELONA SHADOWS

Translated from the Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem

For Eva, Miriam and my parents, who are always there.

Let my death be a greater birth!

JOAN MARAGALL

Cant espiritual

The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague.

EDGAR ALLAN POE

The Premature Burial

Sanguinem universae carnis non comedetis, quia anima omnis carnis sanguis eius est: et, quicumque comederit illum, interibit.

LEVITICUS 17:14

“Didn’t hear what the bet was.”

“Your life.”

CLINT EAST WOOD

For a Few Dollars More

Contents

1

NOW I’M A VOICE INSIDE YOUR SKULL. Or the recitation of someone you love beside the bed, or a classmate who can’t seem to read in his head, or a memory dredged up by a scent. I’m man, I’m woman, I’m wind and paper; I’m a traveller, a hunter and a gentle nursemaid (oh, the irony); who serves you dinner and pleasures you, who beats you up and who listens to you; I’m the drink that burns your throat, the rain that soaks through to your bones, the reflection of the night in a window and the cry of a baby before suckling.

I am everything and I can be everywhere. I behave more like a man (if behave is the appropriate word) than like a woman. And I am referred to across cultures by many different names: The Dark Angel, The Inexorable One (I particularly like that one, it’s from One Thousand and One Nights and I find it quite poetic). But all the Romance languages describe me in the feminine. That has a pretty logical explanation though. Women are the essence of the species, the beginning of it all. Women give life. You are the opposite of everything I represent. We are two ends of the rope. I don’t hate you (I have no feelings, merely curiosity), but I am not like you. I’m more of a man: destructive. Men only know how to annihilate, negate, in all possible senses: to dominate and to kill. But without men, there would be no babies, you could argue. Nonsense. Men don’t give birth. They only possess the female and leave their seed in her, their destructive trace. In a way, he kills her and she sacrifices herself to create a new life. It’s women who give birth and raise the children and make sure everything keeps going. That’s why I wanted to explain Enriqueta Martí’s story to you. Because, despite being a woman, she’s different from the rest.

So, forget about the skulls, the dark robes and the scythes; forget the medieval imagery of gnawed flesh and empty eye sockets, the thick fog and the groans of pain, the chains, the evil laughter and the ghostly apparitions. I’m not the bloke with the cart piled high with corpses, the Supreme Judge or the hooded executioner… even though I can be that. All that is what you are, all of you with your fantasies, fears and nightmares.

I’m not the end of the path: I am the path.

But enough talk about me, which isn’t worth the trouble and doesn’t get us anywhere, and let’s get started, with the story that I’ve come to tell.

And those who know nothing about it say that the first shovelful of dirt is always the worst.

Blackmouth tenses up his body, his ears pricked up like a greyhound’s. He’s surrounded by the scent of damp earth, of One Eye’s sweat, of the salt the breeze pulls off the sea. His hands are frozen on the handle, his eyes bulging, round like the moon whose light splatters the cemetery debris.

The cry of an insomniac seagull frightens them. What was that? Nothin’, nothin’, some bird.

One Eye, tall and lanky, bereft of his right eye from a bullet during the Tragic Week, with a gap-toothed smile and ulcerous skin, digs beside Blackmouth. They hadn’t been to Montjuïc together looking for bodies since the summer. They’d come in One Eye’s carriage, which in the daytime he uses to drive meat from the slaughterhouses to sell in the city, and they’ve tossed the shovels over the fence before jumping over themselves. A single oil-lamp sun is visible from any point on the peak, so they don’t light it until they’re shielded by the forest of funereal sculptures. Don’t want to get caught by the nightwatchman or the coppers, or I’ll end up with the nickname No Eye.

“What does the doctor want with these bodies anyway?”

“What does it matter?”

“He pays us pretty good for something he could just take from the hospital.”

“What do you know about medicine? So let everybody do their own job. The doctor can do his doctoring, and we’ll stick to carting off crates.”

The hole grows deep. The pair of two-bit thieves dig harder and harder; they’ve almost reached the box.

“But he’ll never go to the clink. He’s a doctor and we’re a couple of lousy crooks.”

“Shut up, Blackmouth, and don’t jinx us. You don’t need to worry about him going to prison. You worry about the cops catching you and sending you to the clink. Come on, pull out that grape juice, I’m dripping with sweat.”

Blackmouth pulls the wineskin from the sack and passes it to him. When he gets it back he takes a sip. Experience rules, and his partner had certainly had more whippings over the years. In the end, Blackmouth is just a lad, a chick fresh from its shell, abandoned by his father, mother and God. With no money, eking it out in a pigeon loft on Lluna Street, eating when he can or when he robs, which usually amounts to the same thing. The only company he has is an old blind chap in his building, who gives guitar lessons to children and makes ointments and pomades for adults, which he assures cure all type of ailments, even though he’s been blind and crazy for years. León Domènech is his name, and he never complains when one of the pigeons goes missing. Why do they call you Blackmouth, lad? he’d asked him once, unable to see his teeth stained with dried blood and the dirty feather in his hair.

Hurry up, hurry up, we’re almost done and the sun’s coming up.

Like galley slaves, they focus on their shovels, silent for quite a long while. A thump tells them they’ve hit wood. They wipe the dirt off the surface and search for the nails. Blackmouth pulls two out with his fingernails, bloodying his hands. One Eye works the slit between the lid and the coffin with the shovel blade. Crack, splinters, the door is halfway open. Blackmouth gets excited and lifts it up. He can’t hold back a horrified scream.

“Shit!” mutters One Eye.

“Is this the one we came for?”

“Yeah.” He unfolds a small piece of paper he’d been carrying in his pocket. “Have a look for yourself.”

“I can’t read.”

“It’s a map…”

Standing with the headless corpse between his legs, Blackmouth declares, “Whoever this is, he didn’t die of fevers.”

One Eye comes out of the hole and rests his chin on the shovel handle. He closes his eyes. He’s thinking.

“The doctor’s not going to want that.”

Blackmouth grabs the corpse by the underarms and sits it up.

“Now that’s what I call dead weight.”

One Eye isn’t in the mood for jokes.

“It’s not even fresh. Look at all those worms!” He brings the oil lamp closer to Blackmouth, who discovers that the worms are crawling up his hands and falling onto his trousers. Some of them are making their way into his shoes. He looks inside the corpse’s neck and finds more life there than he was expecting. He searches through the entire coffin for the head.

“Is it a man or a woman?”

“You’re not thinking about keeping it?”

“If I clean her off good…”

“It’s a man.”

“Oh, forget it then, I’m no poof.”

Silence. The seagull approaches them and looks them up and down. It seems to be saying: if you blokes aren’t interested, I won’t turn my nose up at it.

“Maybe the lady will want it.”

Blackmouth turns around, frightened. From inside the tomb, on his knees, the image of One Eye with the shovel and the oil lamp up there, talking about her, makes his blood run cold.

“The lady?”

“Screw up all your courage and let’s get it out of here.”

With the decapitated cadaver inside the sack, they walk to the fence. The hole remains open, with the seagull inside, nibbling on the remains.

“I don’t like the lady,” Blackmouth finally dares to say.

“Don’t start getting daft on me, lad.”

“I don’t like her. You know what they say about her.”

One Eye turns his head to look at him, poor lad. Once they’re in the carriage, he gives him the brass crucifix they took from the corpse’s pocket.

“If you had garlic for supper, then you’ve got nothing to be afraid of.” And he bursts out laughing.

*

“Giselle, you’re the best French whore of all the French whores born in Sant Boi.”

Moisès Corvo sits to one side of the bed, on the wrinkled sheets marked with other clients’ stains dried onto them weeks ago and giving off a stench of sex that floats around the room. Her body lies naked on the bed, curled into an S, with scratches on her back and two bruises on her inner thighs. Her hair is on the pillow and her attentive gaze on Moisès, without any trace of emotion, but also devoid of the fear she usually has after going to bed with whoever can pay for her supper. Moisès Corvo treats her well, as well as that big hunk of man knows how, almost six and a half feet tall and with a thundering voice, strong as an oak tree and arms long like a circus monkey. Giselle caresses his back while he dresses. He’s already put on his trousers, the braces hang on either side, his shirt like a handkerchief in his gnarled hands. He turns his torso, and his mouth smiles in defiance of his deep blue eyes. His face is like an El Greco painting, with messy hair and eyebrows pointy as a notary’s signature, and an aquiline nose as pronounced as his lower lip. You’re like the king, his wife tells him when he’s home. And he’s never sure if she’s referring to his appearance or to his fondness for the ladies, the more naked and dissolute the better.

“Are you coming tomorrow?”

“Who knows. I may be dead tomorrow.”

“Don’t say those things.”

“Then don’t ask silly questions.”

“I’m scared, Moisès. I wish you were here more.”

“Scared of what? Not that scoundrel again, the one who…” Moisès can’t remember his name. Just the sound of ribs cracking beneath the vaulted arch of l’Arc del Teatre.

“No. I’m scared of the monster.”

“The monster?” His hand at his fly, without thinking.

“The streets are full of them. Children disappear. I’m worried about my Tonet.”

“No child has disappeared, Giselle. That’s just gossip from the old crones that hang around in doorways, sick of the gangs of youngsters shouting and jumping around.”

“Dorita’s daughter.”

“Who?” Moisès, standing up, already dressed, cleans his spats with a cigarette between his lips.

“Dorita. She has, she had, a little girl, just four years old. She hasn’t seen or heard from her in two weeks.”

“I’ve never seen that girl.”

“That’s because she doesn’t show her off. You think us whores hang around on the corners looking pitiful with our little ones?”

Giselle, nervous, has also got up and wrapped herself in an old, moth-eaten robe.

“Don’t shout at me.” Moisès heads for the door. He’s got enough headaches from his wife, he doesn’t need more from a hooker.

“Don’t leave!”

“And what am I supposed to do? Stay here all night, waiting for a ghost to show up?”

“I won’t ask you for anything else. Take care of my Tonet.”

“Goodbye.” With a shrug he puts on his jacket and leaves the room.

He’s on the top floor of the La Mina bar, on Caçadors Street. Everyone knows full well what those stairs lead to, but he walks down them with feigned dignity and makes his way to the bar. There’s so much smoke you’d think you were in a railway station. Lolo, short, bald, with the eyes of a sick fish and grease on his shirt, rushes to take his order.

“An anisette.”

“Wasn’t she enough for you?”

“It’s to wash the taste of you out of my mouth, you fuck Giselle too much.”

“It’s a business relationship,” laughs Lolo, and turns tail when another customer calls for him.

Moisès Corvo drinks his glass down in one gulp. Eight o’clock in the evening, too early to start working and too late to head home. Balmes Street is far away. If he waits a while he’ll surely find a friendly face, because everyone there is familiar, but it’s best not to make eye contact, not start any unwelcome conversations. Five minutes later Giselle comes down the stairs, withdrawn, as if she had gulped down all the brazenness she flaunts up there. After an exchange of coins and glances, Lolo blows her kisses and Giselle runs off. She passes Martínez, who looks her over before ordering a nice warm beer and starting to chat with Ortega, who’s so soused that he doesn’t even care that his wife is at home with “Three-Ball” Juli. He’s celebrating having just robbed a couple of British boats stuck in the port, with the help of Miquel, who is now eating a salami sandwich at the corner table (dry bread, incredibly dry meat). Basically just another day at La Mina.

“Lolo!” shouts Moisès over the murmur of voices. The barman comes over to him.

“Another one?” Lolo is about to spit into the glass, to clean it before refilling it.

“No, no. It’s a question.” Lolo leans his head forward attentively. “Have you heard anything about a monster that’s spiriting away children?”

Lolo sucks his teeth.

“Giselle already told you about that… didn’t she?”

“Have you heard anything or not?”

Lolo hesitates, looks from one side to the other, and confirms that everyone can hear them. What can ya do?

“Yes. The girls are pretty nervous. They say that it’s eight little ones now that have vanished. But since they’re… well, you know, since they are what they are, they haven’t reported anything.”

“They’re whores, and the police only want whores for one thing.”

“You said it.”

“Do you know any of the…”

“Yeah, Dorita.”

“Any other one?”

“Àngels.”

“Àngels the Hussy?”

“Do you know any other Àngels? Josefina disappeared two weeks ago. Poor thing, only two years old. Àngels hasn’t left the house since.”

“And how did it happen?”

“Who knows. She must have left her with someone when she was drunk, or she lost her at the market, or God knows where.”

A man with a first-rate moustache leans with both arms on the bar, next to Moisès.

“Lolo, bring me one of whatever this bastard’s drinking.”

“Malsano, I knew it wouldn’t be long before you showed up.” Moisès doesn’t even look at him when he speaks.

“Anise or piss and vinegar?” asks Lolo.

“Isn’t that the same thing in this bar?”

Lolo heads towards the other end of the bar, wondering whether the joke didn’t have some truth to it.

“We’ve got work, Sherlock.”

“Call me Sherlock one more time, Malsano, and I’ll rearrange your face.”

“Hey, hey, hey…” Juan Malsano lifts one hand, peacefully, and with the other he pulls back his jacket to reveal his revolver. “Don’t get all worked up, ’cause we’re six against one here.”

I move closer to One Eye without him realizing, poised to collect his soul. He doesn’t know I’m about to ensnare him. I watch as he hides on Mendizábal Street, waiting for the performance to end. She likes the opera and money. People pretending to be somebody else, the opulent costumes, great passions, tragedies and miseries. A fake world of appearances, convention and protocol, far from reality. A world of masks. At least he isn’t ashamed of who he is, doesn’t need to pretend to be something he’s not. Because he’s no worse than the riff-raff that now paw at their imitation jewels at the end of the show, he says to himself. The pretentious music, which can be heard three blocks away, is over. In a little while, when all the lies have been said, when the mistresses have set dates with the respectable businessmen in some little apartment in the Eixample for a couple of hours from now, the procession will begin. That’s why One Eye hid a few blocks up, because there are too many beggars on the Rambla. The municipal police will be busy beating them back to allow Mr Sostres’s car through, no one will pay any attention to One Eye in this foul-smelling alley behind the Liceu Opera House. Sostres is the city’s next mayor (even though the Lerrouxists and the regionalists tied in the 12th November elections, and he won’t be chosen until 29th December). No one notices One Eye except me, but he can’t see me or hear me now because I’m just a shadow waiting for his soul. One Eye doesn’t get what it is the filthy rich see in that German chap, some guy named Bagner. How many times have the same clowns looked on as some singer bellows out fucking opera, in German, which not even Christ himself understands. Good music is hearing whores scream in a warm bed, he thinks. And he laughs, revealing his missing teeth. Today he won’t rob anyone, even though it’d be like taking sweets from a baby. Today he has come to see her, which is why I’ve come to find him. He has something she might be interested in, because opera and money are not her only passions.

He hears the clip-clop of the horses and knows they are on their way. He can almost see them, dripping with jewels, with their fur coats and their husbands by the arm. How he’d love to have his way with some of them, to show them what a bravura performance is. One Eye shields himself from unwanted glances, in the darkness of the lampless street, until he sees her pass by. She is different from the rest. She walks alone, her head held high, with short, quick steps. Her lips pressed tightly together, her face impassive, like a wax figure. She has her hands crossed over her breasts, which are wrapped in a spectacular deep-red dress, a fancy number that goes all the way down to her ankles. Her hair, pulled back in a bun, reveals a long neck that resembles a column of smoke. One Eye licks his lips in desire. Approaching her is like leaning out of the highest window in a building: the sensation of being about to fall is as powerful as it is irresistible.

One Eye goes out onto Unió Street and follows her for a bit, while there are still people around. It is dark, but not yet dark enough to be the witching hour. The people of ill repute are getting ready to start the night. The worst of them all has just left the Liceu. When she turns onto Oleguer, he quickens his step. He pants, he’s too old for this, goddamnittohell, and shouts, “Ma’am!”

She turns and glances at him, but doesn’t speak. One Eye runs towards her, unaware that it is the last thing he will do before he dies.

When Moisès Corvo and Juan Malsano show up there, two hours later, the narrow street is jammed with people.

“Sherlock Holmes is a pedant. A piece of shit who never leaves his office, thinking he can solve every case like it was some maths problem, just because he’s educated.”

“But he does solve them, right?” Malsano plays along, fanning the flames. He knows how to provoke him.

“He botches it from the very beginning: for him everything is logic, logic and more logic. Even the most irrational.”

“And that’s not how it is…”

“No! You already know that! The world doesn’t work that way: there are errors, misunderstandings, improvisation. Holmes underestimates the surprise factor.”

“But he solves the cases,” declares Malsano.

“Literature. It’s impossible to arrive at the solution to any case by following a chain of deductions, there will always be someone to break it. Criminals play by their own rules.”

“And Holmes doesn’t.” Beneath Malsano’s moustache lies a mocking little smile.

“Not Holmes, and even less Dupin.”

“Who?”

Moisès Corvo pushes aside a man on tiptoe who is trying to catch a glimpse of the dead body. One of the few men, in fact, since most of those present are women. They wear revolted expressions but don’t want to give up their front-row view of One Eye. The outraged man attempts to challenge him, but when he realizes that stocky Moisès would probably just lay him out as company for the deceased, he decides to pipe down and hope that none of the coarse women start laughing at him.

“Dupin, Edgar Allan Poe’s detective, is even worse than Holmes. Holmes, at least, is seen through Watson and Watson’s got a constant crafty streak, even though Holmes is a bully and treats him like shit. Ma’am, out of the way, goddamnit, do you know how late it is?” he scolds. “Dupin is a some sort of crime-solving machine who’s never set foot on the street. I’d like to see him out in the real world, off the page, where all the murderers aren’t stupid monkeys.”

“There must be one that you like…”

“Lestrade. I like Lestrade. A Scotland Yard detective who does his job even though Holmes insists on humiliating him.”

“Moisès, you read too much.”

“And you talk too much, Juan… for God’s sake!”

They reach the cordon made up of two policemen. They can make out the body, or at least its shape, beneath a blood-soaked sheet. The female spectators just cry and grumble disjointed sentences, as if they really cared about the poor wretch laid out there. A cutpurse slips into the unguarded pockets of the few men present who are consoling the women, hugging them close, feeling their breasts heaving against them. Moisès smacks his hand and the pickpocket scurries off like a mouse. One of the municipal policemen, when he sees them arriving, asks the crowd to move aside, but they don’t pay him much mind. He gets tough, furrowing his brow, and finally manages to clear a small path with a couple of threats.

“Asensi, fuck, what happened?” asks Moisès.

“You’re asking me? What do you think? One Eye, who must’ve been waiting for folk to come out of the opera and didn’t know that today he’d be the star of his own show.”

“How’d it happen?” Moisès moves closer, and Juan lifts up the sheet, which sticks to the victim’s body for a few seconds.

“We don’t know. No one saw anything until they found him like this, all sloppy.”

“So no one’s been arrested.”

“You don’t miss a beat.”

Moisès shoots him a look and Officer Asensi understands that he’s used up today’s quota of familiarity. The body is in a puddle of blood, twisted, its hands stiff as claws, with one eye staring at the sky and the other, the empty socket, stuck in hell. He looks like a white cockroach.

Moisès approaches and squats beside Juan, but he’s distracted. All he can hear are the comments of the ring of people, who seem even more excited by his arrival. You fear me, but I’m your favourite spectacle: when I show up, you can’t look away.

They always come when the evil’s been done, he hears a slender woman say.

“Isn’t it too early for this stiffness?” asks Juan.

Moisès touches One Eye’s cold fingers, which now have as much life in them as a banister. His face is out of joint and pale as a candle, his mouth a grotesque grimace. He bled to death, thinks Moisès, but he doesn’t see any wound. His neck is stained with blood, and in the darkness it looks like tar.

“It’s the panic. His death was so sudden that the panic paralysed him.” He rolls up his sleeves, revealing his forearms. “He has no defensive injuries, but from the position of the body it seems the killer was standing right in front of him.”

“He wasn’t expecting it. But how did he bleed to death?”

A monster, hears Moisès. The rumour grows around him.

“Asensi, get all this riff-raff out of here, fuck, they don’t belong at the scene.”

Asensi does as he’s told, but the people basically ignore him. Fascinated, they retreat a few feet and come right back when Asensi’s gaze returns to the dead body. Moisès grabs a handkerchief and cleans the blood off its neck until he finds what he was looking for. A ripped-off piece of flesh, with the skin flapping over it. Moisès sticks his right-hand index finger into the wound, confirming for Malsano, once again, that sometimes Corvo is crazy.

“Right at the jugular. However it was done, this attack was direct and brutal.”

The buzz on the street grows. He’s white! They drained all his blood!

“But this isn’t a knife wound, and it wasn’t made by a firearm either, Moisès,” Juan says, stating his fears out loud. He senses what made that wound, but he doesn’t want to believe it.

“The cut is semicircular, but not precise. As if it had been made with a small saw. But a saw would have been more destructive, and there would be signs of struggle. The body has no other visible blows. In any case, we’ll have to wait for the autopsy…”

“Do you think it’s possible?”

Moisès turns the cadaver upside down, as if he were hauling a sack. And, in fact, that was what it was for him. Just a sack, nothing more than work. He takes off the corpse’s jacket and, with a small knife, strips the shirt off its back. A screech from the crowd gets Asensi worked up again and he is about to pull out his truncheon. But he’s curious too. Moisès carefully looks over the arms. He asks for a lantern, which the other municipal brings him. On his upper right arm there are four small bruises in the shape of a crescent moon. On the left arm, there are three.

“They got him from the front. The aggressor grabbed him from the front… and bit him.”

A woman faints. Moisès turns when he hears the uproar.

“It’s a mouthful,” continues Juan looking at One Eye. “They pulled out that piece of flesh with a bite.”

A reporter arrives, equipped with a notebook and pencil.

“Inspector Corvo!” he shouts.

“Not now, Quim.”

“Come on, man, it’s still warm!”

Juan stands up and addresses the journalist.

“Do you want to feel how warm my fists can get?”

He shakes his head.

“Then shut up.”

From the Ronda de Sant Pau to Ciutadella Park, the rumour spreads that the monster is hungry.

While Judge Fernando de Prat is arriving, a couple of babies cry for their mothers’ attention. As if it were a factory whistle, the spectators begin to file out. Some of them want to make sure their children are at home, sleeping beneath the blankets, even if they’re full of lice. Others would rather not meet up with the magistrate face to face, in case he reminds them that they’re due in court one of these days, that they owe a fine or have a sentence to serve. There are those who suspect that it’s now questioning time, that the police will start interrogating anyone who has a mouth and eyes and, in this neighbourhood, it’s best to be mute and blind. Surely better than being one-eyed like the poor stiff, which is starting to stink, if it didn’t stink to begin with.

When he sees Don Fernando de Prat step out of his Hispano Suiza car into the commotion on Sant Pau Street, with an inhospitable expression, smoking jacket over his pyjamas and a pipe at his lips, Blackmouth turns tail and heads down Om Street towards Drassanes, where One Eye’s carriage sits, still carrying the body they dug up in Montjuïc. He takes it to the port, where the topmasts sway to the slow, deliberate rhythm of the sea breeze and, making sure there are no prying eyes around, gets rid of the body by dumping it into the water, with a crashing noise like a rock falling from a mountain. Blackmouth runs off, leaving One Eye’s carriage. He won’t need it now, he says to himself, and he heads home, to the pigeon loft on Lluna Street, wary of the dark, which is where vampires hide.

Don Fernando de Prat looks obliquely at the body, without much interest, and starts up the usual shop talk with Moisès and Malsano. He acts as if he wants to know what happened, but he’s only thinking about going back to bed once this damn on-call shift is over.

“If we at least had cameras,” laments Corvo when de Prat asks him to prepare a report on what happened for the next day.

“Draw, like you’ve done your whole life.”

“Sometimes life ends, Your Honour, and we move on to a better one. I would recommend you ask our guest for tonight, but I think his reply would be too cold.”

The magistrate ignores Corvo’s sarcasm because the doctor has just arrived.

“Tell me he’s dead, I want to go home and sleep.”

Doctor Ortiz, moustache held high and satchel in his hand, is a man of few words. He crouches over the body and puts a little mirror in front of its mouth.

“Maybe you’ll have more luck with the neck wound, doctor,” says Corvo, who gets no response.

He checks the pulse, looks into the eyes and stands up.

“Take him to the Clínic for me.”

And having said that, he shakes the judge’s hand and heads off from whence he came. He can dispense with formalities. Don Fernando de Prat, Moisès and Malsano know him well enough. Just as they know each other. They’ve all met up many a night around a corpse. And so the judge decides that that’s enough for today and that tomorrow’s another day, God willing. The two detectives wait alone on the street for them to cart off the body, with no more company than a limping dog that groans and stops to lick the puddle of blood off the paving stones.

At number twenty-nine Ponent Street, not far from where One Eye was found, Salvador Vaquer has only been in bed for a short while. He was in the study waiting for Enriqueta to come home. His eyelids were heavy. Then he got up and went to the room of little Angelina, who was sleeping. He locked it with a key and opened the door to a large closet, where Dorita’s daughter sat on a straw mattress. She was crying.

“What’s wrong, pretty girl?” Salvador approached her and caressed her short, clumsily cut hair.

“I’m scared,” she whimpered. “Why? You don’t have to be scared of anything.” Salvador

slid his fingers down the little girl’s neck and then her chest. She’s four years old, at most.

“I want my mummy…”

“I’m here, sweetheart, I’m here.”

Salvador now smells his fingers, which hold the girl’s scent. From the bed he hears keys at the door and the woman entering. A twinge makes him feel guilty, and despite the cold he starts to sweat. He pricks up his ear, like a hunting hound, and he imagines her going first through the dining room, then the kitchen and finally the large closet, where she stops. Silence.

Enriqueta opens the door to the bedroom and Salvador pretends to be sleeping. She undresses in the dark and gets into bed. She embraces him from behind. Salvador bites his lips when she lays her cold fingers on his ribs. She breathes deeply and lets out a whistle from between her teeth that makes him think of a snake. The woman bites his ear and then runs her tongue along the nape of his neck, while her hand slithers down his pubic bone until it catches its prey. He turns and kisses her: her mouth is hot and salty.

Like blood.

2

GREASE SLIDES ALONG THE TILES. The sink is stopped up. The brazier’s embers trace shadows that sway to and fro in a spectral shivering. These are the few signs of life, as misleading as they may be, of the morgue at the Hospital Clínic. On one of the tables lies the sewn-up body of One Eye, white and rigid, with contusions on its back, arms and legs. Less dead than the decapitated body that rests on the table beside it, judging by its smell. They found the corpse very early, floating in the port, beneath a mountain of seagulls. In fact, they wouldn’t have even noticed it if it weren’t for the din of the big birds screeching and fighting for a piece of rotten meat in front of the statue of Columbus with its outstretched finger. Doctor Ortiz believes that the discoverer of the Americas was pointing out the dead chunk, as if asking them to get it out of there. Now the doctor taps the floor with his feet, first the right, then the left, to drive out the cockroaches that smell a banquet.

“Have you started the party without us?” bellows Moisès after coming down the spiral staircase that leads to the autopsy room. “I hope I won’t have to dance with the ugliest girl…”

And he looks at the headless body. Doctor Ortiz furrows his brows and shakes his hand. He does the same with Juan, who comes down behind him.

“Good evening.”

Everyone knows it’s a figure of speech. Doctor Ortiz doesn’t think this is a good evening. He doesn’t even think it’s a good anything. He called them in because he wants to show them something on the corpse with the bite mark.

“Let’s get down to it, doctor,” pressures Juan. “We’ve hardly slept today and I’d like to take a nap before the shift is over.”

“I think there are still some free beds, if you want, and even some company, the kind that doesn’t complain much,” replies Moisès.

“Is the comedy show over, gentlemen, or am I going to have to start charging admission?”

“And what about this one? Do we know what it’s doing here?”

“He just came in a little while ago.” The doctor pats the chest of the body, since it has no head, and a stream of insects splashes onto Juan’s feet.

“Goddamnittohell!”

Moisès leans over the corpse, covering his nostrils and mouth with a handkerchief that has his initials embroidered on it. It is the only thing of his wife’s that he carries with him.

“Here we have the best proof that, indeed, there is life after death. A lot of life.”

The stench is almost unbearable, and with the brazier it is asphyxiating. Doctor Ortiz knows how to make sure visitors don’t overstay their welcome.

“As I said, he had already been a client of mine. A poor wretch who threw himself onto the railway track and ended up like this… well, not quite like this.”

“And what was this Marie Antoinette doing in the port? Now even the deceased are in on this stupid swimming craze?”

“Mr Corvo, I’ll pretend I don’t hear your insightful comments and I’ll refer you to your colleague, Inspector Sánchez, who is handling the case.”

Buenaventura Sánchez. The perfect policeman. If Juli Vallmitjana wrote about the coppers instead of about the plebs, Buenaventura would be the main character. Tall, handsome, with spiky hair and light eyes, a hypocritical smile and pat on the back, a guy who knows everything about crime and how to fight it. A policeman so perfect that he’s the apple of his boss’s eye. The district chief of Barcelona, José Millán Astray, can’t stop listing his virtues while Buenaventura brings him warm milk and tucks him into bed. With everyone else he acts like a know-all, like someone who knows he’ll go far, or at least thinks he will. Juan Malsano can’t stand looking at him, and Moisès Corvo has already broken his face once.

“Has Inspector Sánchez been here? I think I can smell his perfume…”

“He came this afternoon, Inspector, with Doctor Saforcada, who did the autopsy on the subject I called you here about.”

“And what did Doctor Saforcada find?” asks Juan.

“Your monster. It’s human. Or at least, a human with nec-rophagous tendencies.”

“So we can rule out the Wolfman or Count Dracula?”

“Inspector Corvo, come here.” He stands beside the table and grabs One Eye by the arms. “Four ecchymoses on one arm and three on the other. What does that tell you?”

“That they held him down before he died, from in front. Someone with some strength…”

“Don’t tell me something we all know already. Think. Why are there three on one arm and four on the other?”

“Because the killer has missing fingers?”

“Ectrodactylism. That’s a possibility. And it would definitely limit the search field.”

“Our fingerprint archives are still small,” says Juan, running his fingers over his moustache. He has been breathing in that same air for so many years now that he barely smells the odour of putrefaction except when he takes off his clothes in the morning, before getting into bed.

“Yes,” continues Moisès, “Professor Oloriz is just now supervising the archives’ creation. And to top it all, there’s all sorts of people coming back from the war against the Moors missing a hand, with their trousers knotted up at the knee, or in a pine box.”

“I said it’s a possibility. What’s the other?” Silence. “That one of his hands was busy with something else.”

He moves One Eye’s body like a dried-out baguette and pushes it closer to the lamp, revealing a fourth bruise, smaller and longer than the rest.

“He was carrying a knife?”

“A knife would have left a cut. It must have been a pointed tool, like a bodkin.”

“But there’s no bodkin wound either.”

“Not at first glance, but we didn’t bring him here to sing us a zarzuela, did we?”

“If you want your part of the ticket money for the show, doctor, all you have to do is say so,” grumbles Moisès.

The doctor positions himself to touch One Eye’s head, shaved and sewn up clumsily, and opens the neck wound. You spend half your life seeking me out and the other half running from me. You rough up the corpses, jab at the flesh, looking for explanations inside the bodies that bear my mark. Who? How? Why? The answers are within these men’s reach, these men that shuffle around dead bodies like someone looking for the answer to an arithmetic problem.

“This is a human bite. We can tell from the diameter, from the way the skin is broken and the teeth marks, which fit with a human odontogram. But the killer’s first attack wasn’t the bite. He would have to have been a real big brute to just grab somebody, even a very weak victim, and bite off a piece of their neck.”

Moisès looks inside the opening, but doesn’t make out anything.

“Here,” continues the doctor. “This cut on the inner part isn’t consistent with the bite, but with a lacerated-contused wound stemming from a weapon, such as a bodkin.”

“Such as a bodkin.”

“Or a hairpin.”

“What murderer wears a hairpin?”

“What murderer drinks their victim’s blood?”

Moisès Corvo closes his eyes and the memory of Rif comes flooding into his head, as vivid as the warmth of the room he is in. Soldiers who eat human flesh in order to survive. Were they monsters then? He himself had cut off the enemy’s fingers and ears as some kind of stupid souvenir of his tour of Africa; was he a monster?

“Who could do something like this?” asks Juan.

“You two are the policemen, gentlemen. I’m just a doctor. There you have the clothes, which haven’t been inspected.”

Moisès picks them up off the table and separates them. He starts with the wrinkled jacket, then moves on to the shirt. It feels like parchment where the blood has already dried, and slippery where it’s still damp. There doesn’t seem to be anything useful, until Juan pulls a crumpled piece of paper out of the trousers. It’s a map, written in pencil. On the back, they couldn’t have had a better stroke of luck: it’s a doctor’s business card.

“Doctor Isaac von Baumgarten,” reads Juan. “Do you know him?”

“No.”

“But you’re both doctors…” he replies, annoyed.

Doctor Ortiz bites his tongue. They’ll be leaving soon and he’ll be left with the only company he gets along with, the dead, who are considerate enough not to spend the night saying stupid things and expecting a nice response.

Barcelona is an old lady with a battered soul, who has been left by a thousand lovers but refuses to admit it. Every time she grows, she looks in the mirror, sees herself changed and renews all her blood until it’s almost at boiling point. Like a butterfly’s cocoon, she finally bursts. Distrust becomes the first phase of gestation: no one is sure that he whom they’ve lived with for years, whom they’ve considered a neighbour, isn’t now an enemy. All of a sudden they put up walls, making obvious the differences among Barcelonians, and each one takes refuge in his own universe, prepared to defend or attack. And this is how violence, the second phase in the metamorphosis from bug to butterfly, becomes an irreversible phenomenon. Over some petty thing, some groundless motive, some made-up excuse, the old lady is once again covered with scars and burns; she screams madly and pays homage to me. These are days when I stroll openly through the streets of a city devoted to me, and I enter a thousand bodies anxious to please me. I collect souls in abundance, without paying attention to names or faces. Slain Jews and monasteries in flames. Blood and fire create the soot that will be the make-up Barcelona smears on to become old again. Renewal as the final step, the pretence that nothing happened although now everything is different, will make the city both a wiser woman and, at the same time, a more aggrieved one.