Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

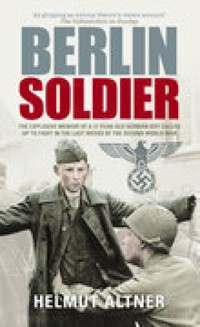

This book is an explosive memoir of a 17 year old German boy called up to fight in the last weeks of the Second World War. This is a teenager's vivid account of his experiences as a conscript during the final desperate weeks of the Third Reich, during which he experienced training immediately behind the front line east of Berlin, was caught up in the massive Soviet assault on Berlin from the Oder, retreated successfully and then took part in the fight for the western suburb of Spandau, where he became one of the only two survivors of his company of seventeen year-olds.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 573

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BERLIN

SOLDIER

About the Author

Helmut Altner, the author, worked for decades as the Paris correspondent of several German newspapers, and has now retired to live just outside the city.

Tony Le Tissier, the translator and editor, is an acknowledged expert on the 1945 battle of Berlin. His other books include, The Battle of Berlin 1945 (also published by Tempus), Slaughter at Halbe: The Destruction of Hitler’s 9th Army - April 1945, With Our Backs to Berlin: The German Army in Retreat 1945, Death Was Our Companion: The Final Days of the Third Reich, Farewell to Spandau, and Berlin Then and Now. He lives in Lymington in Hampshire.

This edition first published in 2007 by Tempus Publishing

Reprinted in 2008 by The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port, Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

This ebook edition first published 2016

All rights reserved © Helmut Altner, 2002, 2007 Translation, Annotations and illustrations copyright © A H Le Tissier 2002, 2007

The right of Helmut Altner and A H Le Tissier to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 7979 5

Typesetting and origination by Tempus Publishing Limited

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Introduction

1 Called Up

2 Off to the Front

3 Recruit at the Front

4 Training in the Trenches

5 The Storm Breaks

6 Retreat

7 Defending Northern Spandau

8 The End in Spandau

9 Stresow & Ruhleben

10 The Tunnels

11 Back in Barracks

12 Breakout

13 Flight

Appendix 1: Execution Place No. 5 – The Murellenschlucht

Appendix 2: The Underground Factory

Appendix 3: The Situation in West Berlin – 27/28 April 1945

Appendix 4: The Hitler Youth in Combat

Notes

List of Maps

Introduction

This is a teenager’s vivid account of his experiences as a conscript during the final desperate weeks of the Third Reich, during which he experienced training immediately behind the front line east of Berlin, was caught up in the massive Soviet assault on Berlin from the Oder, retreated successfully, and then took part in the fight for the western suburb of Spandau, where he became one of the only two survivors of his company of 17-year-olds. He later fought in the U-Bahn tunnels and in the battle for the Reichssportfeld. Then, on the morning the city capitulated, he took part in the breakout to the west that turned into a bloodbath for soldiers and civilians alike. Wounded, he was captured near Brandenburg on 3 May 1945.

The detailed description of his experiences makes it still possible today – over fifty years later – to walk in his footsteps. His book, based on notes made in a diary that survived eighteen months of Soviet captivity, was originally published in Offenbach in the spring of 1948 after clearance with the US Military Government and the necessary allocation of paper to print it on.

Helmut Altner’s account ties in with events outside his knowledge as a simple soldier, so I have supplemented his text in this revised edition with notes, drawings, appendices and photographs. His regimental command post, for example, was located in an underground factory that had last been used for assembling V-Weapons, but had actually been intended for the production of poison gas and eventually was to be used by the Soviet Army as a secret headquarters in case of nuclear warfare.

Two words or expressions used in the translation will perhaps strike today’s reader as rather odd: ‘child’ as applied to a 17-year-old and ‘comrade’. At the, time of the Third Reich there was no word for teenager in the German language, and the use of the word ‘comrade’ has been maintained from the original German text as it had a specific meaning for the German soldier for which I can find no adequate English equivalent.

Tony Le Tissier Frome February 2002

1

Called Up

Thursday 29 March 1945

Berlin seems to be falling apart at the seams. The nightly bombing raids have inflicted far greater damage than the official communiques indicate. According to them only a few buildings in Spandau have been destroyed, but the actual situation looks far worse. The U is running irregularly, and half hour delays are no exception, while the S-Bahn, with most of the tracks damaged beyond recognition, is almost completely at a standstill.1

I am standing hemmed in between thrusting, pushing passengers on an S-Bahn train between Velten and Hennigsdorf. My luggage, which consists of a Persil carton containing something to eat and some underwear, is stuffed somewhere in the carriage’s luggage rack.2 At Hennigsdorf I am forced out onto the platform by the rush and have to use my elbows ruthlessly to get back in to recover my baggage and then jump off the already moving train.

I follow the stream of people down the steps to the station exit, the call-up papers in my pocket already making me feel as if I no longer belong with these people. I make my way to the tram stop from where a tram should take me to where I have to report. The traffic island is already full of people who cram into the tram when it arrives. As everywhere in the Berlin street scene, the field-grey uniform predominates.

After a short while the conductor rings the bell and we move off. I stand on the rear platform and can see the road go by. We leave Hennigsdorf behind us and pass through meadows and woodland to where Route 120 comes to an end and the connecting tram is waiting for us. Soon the first villas in Spandau appear and we can see the consequences of last night’s bombing. Ripped apart sections of woodland and shattered venerable old oak trees bear witness to the destructive effectiveness of modern explosives. Then burning houses whisk by, attended to by troops of soldiers and Hitlerjugend armed with fire-extinguishing equipment, while several boys in uniform collect up torn apart pieces of human bodies and a 12-year-old stands by calmly eating his breakfast roll.

The tram stops and we have to get off. I take my carton and go on past the wagon. Several metres farther on the overhead cables have been destroyed and are strewn across the road. We will have to wait to see how we can go on.

A few others with Persil cartons have got off the tram with me, and after some hesitant glances, contact is established; we all have the same goal.

With a combined effort we manage to stop a truck, which quickly fills with people converging from all directions, men and women who are clearly moving out of certain areas and others wanting to visit their relatives in the bombed parts of the city to find out if they are still alive. Every vehicle we come across is full of exhausted people. Rumours, every one worse than the other, swirl about us, making us even more unsettled than before.

We rapidly approach the centre of Spandau and here, for the first time, we see the powerful extent of the damage. The empty window frames of a burnt-out factory across the way stare accusingly at the world, fallen beams glowing gently and occasionally flaring up with the breeze, while the owners of a still burning house watch from across the street speechlessly as the fruits of years of hard toil go sky high. Dark figures slink through the destroyed quarter, looking about them furtively like hyenas on the prowl. Berlin, the nerve centre of the Reich, has been turned upside down.

The farther we penetrate this destroyed, burning quarter, the more depressed we get by the atmosphere. Women are crying quietly, stopping people to ask anxiously about certain streets and if many have been killed. They are answered in low voices. One no longer recognises in these faces the heroism mentioned so often by Goebbels in the first years of the war.3 On the contrary, one sees only a dull, undisguised despair.

We have to leave the truck just before the town hall, where it turns quickly down a side street. We shoulder our cartons and ask our way to the von Seeckt-Kaserne.4 As we pass Spandau town hall, Civil Defence and Fire Brigade personnel are trying to extinguish the fire in part of the building that is burning like a torch. The streets are strewn with glass splinters and rubble, and people rush by, thoughtlessly trampling the first signs of greenery thrusting through the earth all around them.

The destruction extends as far as the S-Bahn line and then stops abruptly as if drawn with a ruler. On the far side of the line the only reminders of the war are the street barriers and the barracks. At the guardroom of the splendidly built barracks, the conscripts’ call-up papers are taken from them and returned stamped with the date and time of arrival. I am a soldier now and there is no turning back.

I go along the smooth asphalt street. Soldiers’ voices come quietly from the large blocks on the left, and on the right a platoon marches across the square to the cookhouse. At the far end of this gigantic barracks, complex scaffolding surrounds even more buildings under construction. While the homes of the civilian population are being reduced by smoke and fire, new palaces for recruits continue to be built.

In the company office several clerks are lolling about, completely ignoring me until a second lieutenant comes into the room, when they all contrive to look busy. The subaltern examines my call-up papers and then snarlingly asks me why I am two hours late. Then my details are recorded and I am ordered to report to Grenadier Training & Replacement Battalion 3095 in the Alexander-Kaserne6 at Ruhleben. Just as I am leaving, the clerk tells me that my mother is waiting for me in the canteen. I feel as if I have been hit. Overwhelmed with delight, I almost forget to salute as I dash out.

It is all too much at once. For months I have had no news of her and suddenly I am to see her again. I quickly go across to the canteen, where mother is sitting at a table eating her lunch and does not see me come in. I go up to her slowly and she looks up as I stand in front of her. ‘Mother!’ is all that I can say, and we are reunited.

We return to the company building together and sit in the corridor. A whistle blows and recruits dash past us, but we continue talking, the world outside forgotten. There are battle scenes on the walls, of cavalry with colourful, fluttering flags and infantry on the march: how peaceful the war seems in here!

We have lost all sense of time, but a clerk calls us back to reality. We go through the destroyed town quietly, making the most of every moment before the barracks gates close behind me. Barricades are being erected on the bridges across the Havel, and below in the water lies a sunken barge from which bare-legged men and women are busy salvaging preserves and ham to augment their rations. A dead man floats on the slightly raised bow, turning in the waves, his glazed eyes staring into infinity, but no one pays him any attention, for food is far more important.

At the Alexander-Kaserne, which is of older construction than the Spandau barracks, the induction process through various offices begins. Every little clerk thinks himself God Almighty, exercising his authority with a loud voice. The lower the rank, the louder the voice. Two hours later, during which mother has been waiting, standing in the corridor, it is all over. I have lost my civilian identity card in exchange for a paybook and identity discs. Other new arrivals, both young and old, jostle in the corridor. Is this all that Germany has left to offer?

I climb the stairs to the attic with my mother. The higher we go, the more dismal the corridors seem. It is bitterly cold in the attic where I am to spend the night, and every time the door opens, the windows rattle in their frames. Some double bunks are scattered about the sloping-sided room with a couple of doorless lockers, some tables and wobbly stools. A few old sweats are sitting at a table talking about the war. I sit down on a bed with my mother and we look about us silently in the slowly darkening light. Behind us we hear the voices of some soldiers who have lit candles. None of them believe in victory any more, and they say that they will desert as soon as they can.

mother is desolated by the wretched surroundings, the old sweats’ talk, the atmosphere. She turns to me sadly: ‘You won’t experience much happiness, my boy, but my best wishes go with you all the same.’ Then it is time for her to leave, so we go down the stairs slowly and out into the starlit night. The sound of voices comes from the brightly lit barrack-rooms and somewhere a flute is trilling. My worried mother tells me to look after myself. We look each other in the eyes once more, a final handshake and the outline of her beloved figure fades slowly in the darkness.

Friday 30 March 1945

I am woken up at seven o’clock by the shrill whistle of the orderly sergeant. The morning light is showing through the small windows. At last we new conscripts are issued with the eating utensils and the blankets that we needed so badly the night before, but yesterday the high and mighty quartermaster had had no time for us.

We are given some hot coffee and told to fall in. It occurs to me that today is Good Friday, the weather matching the occasion with a dull, overcast sky.

We newcomers in civilian clothes have to parade on the right flank of the company on the square. A fat sergeant major sorts us out as we stand all mixed up together, 16-year-olds next to 60-year-olds: Germany’s last hope!

Our group is assigned to a very young sergeant, who marches us to the medical centre for inoculations. We take off our clothes in the anteroom, which reeks of sweat and leather, and wait freezing for the inoculations to begin. At last we are admitted in threes to the treatment room, where an elderly medical officer with the typical grating tone of a professional soldier looks us over quickly and declares, ‘Fit!’ In the next room we each get three injections against cholera, typhus and malaria, one in each arm and one in the left nipple. The doctor and medical orderlies work like machines. ‘Fit!’ – injections – stamp in the Pay Book – ‘The next – quicker!’ They do not see bodies any more, just numbers, flesh destined for slaughter.

I am not affected by these injections and tackle the tasty pea soup at midday with a healthy appetite, but many of the others are, and cannot eat their lunch: all the more for us. They have pains in their arms and are white-faced, their bodies lacking the reserves to take this kind of treatment.

In the afternoon we get our first items of uniform from the quartermaster’s stores. The individual items are thrown at us after a quick appraisal of the figure. ‘OK? Out!’ It is only when we get back to the barrack-room that we can really see the things properly. My jacket is too big and flaps around my body, the sleeves reaching down to my fingertips. On the other hand, the trousers barely reach my knees and the boots pinch. ‘OK?’ I am not the only one. Most of my comrades look either as if they are scarecrows or wearing their first school uniforms. Only by exchanging items can we gradually achieve some semblance of reasonable dress. Now all but the boots fit me, but two of the boys face the daunting task of returning to the quartermaster’s stores to ask for exchanges.

Late afternoon we get an issue of ten cigarettes and some schnapps to celebrate the holiday, the youngsters also getting extra bread and fat with their cold rations. In the evening I go along to the well decorated canteen for a beer. Furtively, I examine an old serviceman sitting at my table with blond hair and a squarish head, obviously a sailor with the blue of the sea mirrored in his eyes, and I get talking to him. He is 58 and comes from Hamburg. His name, Hermann Windhorst, sounds of storms and the sea.

‘Retreat’ sounds and we have to leave the canteen and go to bed. He is in the same barrack-room as myself, and in the same corner, so it is surprising that I have not seen him before.

I am woken up by noise and swearing during the night. Whistles are shrilling in the building and out on the square as the last notes of the air raid sirens sound. Drunk with sleep I climb into my boots and feel my way through the darkened room down the stairs. One can already hear the sound of engines in the darkness; Mosquitos.7 Several bombs explode in the city centre and searchlights sweep the skies. Two hours later we return to our beds tired and frozen through.

Saturday 31 March 1945

At breakfast there is sweet milk soup for a change which, tired and hungry, we eat gladly. Further items of equipment are to be issued during the morning, and we are expected to appear in uniform for lunch.

Back in the barrack-room I pack my last items of civilian clothing with a last somewhat painful thought as I close the carton. Farewell civilian life! I am now a soldier. The last barrier has fallen.

Shortly before midday we suddenly have to parade again. Our platoon has to go to Spandau for blood tests. While new arrivals are coming in every day, our platoon is naturally not fully in uniform, so we march separated, ourselves in front, the civilians behind, each with a sergeant as the right marker and Staff Sergeant Becker as the Platoon Commander. It is a lovely sunny day, real spring weather, and the people on the street stop and watch our mixed marching column, some eyeing the youngsters in grey uniform with sad expressions.

Spandau is busy. Anti-tank barriers are being constructed on the Havel bridges8 ready for closing, and engineers are setting demolition charges. Preparations for defence in the middle of the city, and yet we are being told daily that we are winning?

Several groups are standing in the von Seeckt-Kaserne, waiting like us to be dealt with, while recruits are being put through their paces on the drill square by sergeant majors and sergeants. I recognise several of them from Labour Service.9

Now it is our turn. We go in single file past a medical orderly, who pricks us in the forefinger and squeezes out a drop of blood, then a bit farther on we stick our fingers in a jar filled with a light liquid. Afterwards the medical orderly tells each one his blood group. I am A.

We march back in formation to the barracks, where our blood groups are stamped on our identity disks in the armoury. Then it is time for lunch. We stand in a long queue in front of the cookhouse with soldiers coming in from all directions. The Hungarians stationed in the barracks form a separate group. A few soldiers at the back of our queue start a quarrel with them, provoking a heated response from these sons of the Balkans. The result is that they now have to wait until all the Germans have been served. They stand aside angrily with hungry eyes, the remains of a once so proud Hungarian Army who now go about in torn brown uniforms and with dark eyes reflecting their longing for the wide expanse of their homeland. They have no rights and are beaten and kept apart from their German superiors, intimidated and anxious.10

In the afternoon the recruits are summoned from their various barrack-rooms. We move together to the medical centre, where we get straw from other barrack-rooms to stuff our palliasses. I have picked out the best sleeping place, protected on three sides with only a small gap giving access to my bed, so that I do not have to be afraid that the orderly sergeant will give me a rough awakening one morning. My upper bunk mate is a Berlin High School boy with whom I share a large locker and the first thing we do is to store our things in it for the present.

After we have been released from duty, I go to the canteen with him, where we meet another of his school friends, and together we raise a few glasses and drink to brotherhood – Heinz Boy my locker mate, Fritz Stroschn, Günther Gremm and myself. With darkness the canteen fills up and the tobacco smoke is thick enough to cut with a knife, so we go outside and arrive just in time for the issue of the evening rations. In our barrack-room ages range from 17 to 35 and the sharing out of rations proceeds with an astonishing lack of friction. Later on we sit and eat our supper by the light of a flickering candle while behind us there is a game of Pontoon being played at the table. A pleasant Organisation Todt11 man, still in his brown uniform and in civilian life a ship’s cook, laughingly loses trick after trick. The banker, a witty railwayman whom we call Alfons, smilingly gathers in the winnings. But fortune is capricious, and when Stroschn has a try, he wins RM30 off him in one go. Then this idyll is shattered when someone bursts into the room with the cry ‘Orderly sergeant!’ and money and cards vanish like lightning.

The candle burns gently. I have lain down on my bed and hear my comrades talking as an indistinct murmuring in my subconscience. No sooner has the barrack-room orderly swept the room and reported to the orderly sergeant than the sirens sound and we have to dive into our things and go down to the shelter together.

There one soldier relates how he was a member of a court martial after 20 July 1944 and sentenced 108 soldiers to death. ‘All asked to be sent to a Punishment Battalion,’ he says, ‘hoping to eventually survive that way, but if things went badly they would be shot anyway.’12

Bomb explosions sound quite near. When the ‘All Clear’ sounds the sky is full of light, for some buildings are burning in the east with red-gold smoke far into the night. One can hear sirens howling in the distance as the metropolis breathes out and climbs out of its cellars once more.

Sunday 1 April 1945

Today is Easter Sunday. The weather is misty and it looks like rain. We get a special celebratory sweet soup for breakfast. There is not much food and we are always hungry. It tastes good enough, but the larder is bare.

We are off duty. Stroschn and I sort out our locker, folding and arranging our things in apple pie order with the smaller items stuffed in behind out of sight.

Then the staff sergeant summons us below to make a tour of the barracks. He shows us the rifle ranges in the exercise area next to the buildings, where a Labour Service flak unit has its guns deployed, and the boys of the Home Defence Flak13 swagger past us in their flashy blue uniforms with white neckerchiefs. Beyond is a tank wreck used as a target for Panzerfausts.14

There is a neat group of houses just below the Reichssportfeld escarpment, whose windows glint in the light of the sunshine as it breaks through. People are standing around in their Sunday clothes, their laughter carrying across to us, but there is an unbridgeable gulf between us.

We stop next to a clump of bushes with a few withered pine trees, where three posts have been rammed into the ground. This is the capital’s Execution Place No. 5, where deserters, traitors and saboteurs are shot. The wood of the posts is splintered by bullets and dark streams of blood stick to them as if burnt on. The soil is dark red. Human blood!15

We march back in somewhat thoughtful mood. Some guns are standing rusting in the woods beside the rifle ranges. Why are they not being used? Nobody seems to know.

For lunch there are boiled potatoes, meat and gravy, with pudding to follow. Later the sergeant gives out the cold rations for supper together with a special issue of twenty cigarettes, a quarter litre of schnapps and half a bottle of wine each. Now we can really celebrate Easter.

In the afternoon I lie on my bed and read. Boy has a visitor and with Stroschn we eat the celebration cake that has been brought for him. When she is leaving, his mother asks us to take care of her son, which we gladly promise, but Boy is embarrassed. In the evening we go to the canteen and discuss our uncertain future with Hermann, who is also there.

Shortly before ‘Retreat’ the sergeants return drunk to the barracks from the city. Only ‘The Scarecrow’, whose overlarge uniform flaps around his body, is still sober. His girlfriend came to visit him at midday and he has been otherwise engaged.

Monday 2 April 1945

Easter Monday, the day of peace and spring, has lost its meaning in this murderous world.

In the morning we take our cartons of civilian clothes to the company office to be sent on by post to our next of kin. I go back to the quartermaster’s stores once more and press some cigarettes into the hands of the relaxed-looking sergeant major. Now I can sort out a new greatcoat and some good trousers for myself. How the holiday – and some cigarettes – can change the demeanour of some people!

As I am about to return to my barrack-room, a grey-brown column of soldiers wheels into the square singing mournfully. These troops go past singing in brand new uniforms with shiny SS collar patches and white fur hats. These are not German voices, nor is the song German. They are Vlassov Troops – Russians.16 In their mournful singing, in which the lead singer starts off and the refrain is taken up powerfully by the rest, breathe the vast distances and plains of the Russian landscape. These Russians are officer cadets in the Vlassov Army, an army that hardly exists any more. They have been trained to use German weapons and are just like the Hungarians – cannon-fodder.

At lunchtime, like yesterday, there is food again. The sergeants go out once more on a city pass and ‘The Scarecrow’ has a visitor again. When we go to collect our cold rations, we catch him in a not quite ready condition for receiving visitors and discreetly withdraw.

Later I lie on my bed and doze. Then Boy, Stroschn and myself go along to the canteen together to write postcards to our mothers before returning to the barrack-room and trying our luck at cards. By bidding carefully I win RM30. Today’s issue of alcohol helps the congenial atmosphere, which is peaceful. We three friends play another game of Skat together, and later Staff Sergeant Becker comes along and joins in. Boy and myself are the barrack-room orderlies, so shortly before ten we chase everyone to bed and sweep out. The staff sergeant inspects the room and we are dismissed, switch off the lights and are soon fast asleep.

Tuesday 3 April 1945

Today our training is to begin. The day hardly starts well, for Sergeant Rytn has a hangover and is in a bad mood. After we have drawn our morning coffee, he marches us ten times round the barrack block with our steaming mess tins singing the same song over and over again.

The other companies are already falling in outside their barrack blocks, and we are cold with anger. Just because this youngster, no older than ourselves, wears a sergeant’s insignia on his collar, we are entirely at his mercy. One could cry with mortification.

We have no time left for breakfast. We swallow down our cold coffee and fall in again. Then we have to collect equipment from the armoury – ammunition pouches with ten rounds, gas masks and gas capes. The sirens go off while these items are being issued and we go to the bunkers. We can see the first Mosquitos flying east like flies in the sky. When the ‘All Clear’ sounds the sun is shining brightly on the earth and a few giant mushrooms of smoke are rising above the city centre.

Staff Sergeant Becker has the youngsters fall in. The others can go back to barracks with the sergeants. It seems that something special has been lined up for us.

As we march off toward the ranges, Staff Sergeant Becker explains to us that an execution is to take place today and we have to watch. He adds with a smile that our company commander, Lieutenant Stichler, has given the order for this in order to strengthen our nerves.

A small grey van with barred windows is standing under the trees next to the ranges. We stand on the edge of the woods and keep quiet. The door of the van opens. Three men in green denims are sitting along one side, a grey-haired civilian, the padre, and an SS staff sergeant on the other. When one of the prisoners gets out, we can see that he is wearing handcuffs. Behind him is the SS staff sergeant with a pistol. The prisoner says something to him with a smile and gets slowly back into the van.

The waiting gradually makes us nervous, and the chatting has stopped. Two SS men, former comrades, appear and shake the prisoners by the hand once more. Then they vanish between the trees. It all seems unreal to me – the woods, the birds singing, the sun in a cobalt blue sky. And we have to wait to see how men are murdered, the spectacle diminished as if it were nothing more than a play at an annual fair.

Our staff sergeant speaks with the SS escort. He tells us that this morning one of the prisoners tried to escape during his medical examination and was knocked down in the doctor’s waiting room. All prisoners have to be declared medically fit before they are shot. What a mockery of humanity! One has to be physically fit in order to be shot!

The hastily assembled firing squad, formed from all the companies, marches up from the barracks. The task is not liked and everyone tries to avoid it. Only one tall, freckled soldier has volunteered.

We wait for the Judge-Advocate officer to appear. An open-sided truck comes round the corner carrying the three coffins, whose black polish gleams in the sun. We watch the prisoners, who are paying no attention to their surroundings but hanging on the lips of the padre as if they were already in another, better world.

At last the vehicle appears with the doctor, the Judge-Advocate officer and a clerk. The officer jumps down lightly, the sun reflected on his gleaming, patent leather jackboots. He casually touches a finger to his cap and looks briefly at the van, then beckons the clerk and walks to the execution place.

The occupants of the van climb out. With the padre praying beside them they slowly go towards the firing squad. They are all wearing handcuffs. Loud commands ring out over the area. The firing squad has taken up position and the three open sides of the square are covered by two men to prevent an escape. Quietly, as if not to disturb anyone, the staff sergeant gives us his orders and we move up to the execution place. We take position to the right of the firing squad with the smaller ones in front so that everyone can see. A few officers’ wives stand around chatting: ‘An exciting show, isn’t it, Mrs Lieutenant?’

The prisoners shake the padre’s hand for the last time. He raises his hands in blessing and draws back. The Judge-Advocate officer stands in front of the posts with his clerk and leafs through his papers with the prisoners standing in front of him. The three men’s fate will be determined in the next few seconds. They can still be reprieved even with the execution posts staring them in the face.

The silence is uncanny. Everyone watches the group of men, hardly daring to breathe. Even the women have gone quiet and hang on the lips of the Judge-Advocate officer. He clears his throat and the words drop one by one into the silence: ‘Sentenced to death by shooting. The appeal for clemency has been rejected.’

The words hang in the air for several seconds. The condemned men have hung their heads. The youngest is 18, the others not much older. The officer withdraws and the clerk vanishes into the crowd. Three soldiers step forward and release the handcuffs. The denim jackets are removed and they place themselves at the posts, two pale-skinned, well-developed youngsters with blue eyes, the third a smaller, frailer lad. They are fastened to the posts with leather straps, their chests trembling under their thin shirts. Once more they look at the bright sunny day. Their children’s eyes take in the beauty of the morning as a memory to take with them to the other world.

The firing squad takes aim. ‘Goodbye, comrades!’ a high-pitched voice calls out and then the officer’s shining dirk drops. ‘Fire!’ Suddenly all the posts are empty and blood runs from the wood as if it itself has been killed. The doctor checks the shot men. The little one raises himself once more and blood flows from his mouth. The doctor puts his pistol to his temple and presses the trigger. The shot sounds muffled.

Sharp orders ring out and the firing squad withdraws. I have a bitter taste in my mouth and, as we march back, we all look unnaturally pale.

A truck overtakes us by the barrack gate with its cargo of three coffins.

Back in our barrack-room we move around in silence. The older men bombard us with questions but get no answers, and at noon we are unable to eat anything. But the Judge-Advocate officer sits in the dining room with his cheeks stuffed full, cracking jokes.

The lieutenant arrives after lunch. Some of the men are to be sworn in and tomorrow they are off to the front, but none are from our barrack-room and they are all older men. The dining room is decorated with the Reichs War Flag on the wall and two machine guns set in front of it. The persons concerned undergo a big kit check prior to being sworn in.

I go to the canteen with Boy and buy two pounds of salted herrings, and then we drink of litre of beer to give the fish something to swim in. We have to get sozzled to forget what has happened. When we get back the swearing-in ceremony is already over and addresses are being exchanged. Friendships had been made, but now everything is being torn apart again. Such is the lot of a soldier!

At night I lie sleepless on my bed. The moon hangs like a yellow disk in the sky. I see the youngsters at the posts in front of me, how their chests rise and fall, how their eyes seek the blue of the skies. And their end. Will it happen to me too? Should I weaken, I would prefer death from an honourable bullet.

Gradually the day dawns and I fall into a light semi-sleep. The duty NCO’s whistle blows and I get up still tired.

Wednesday 4 April 1945

This morning everything has to be at the double. The sergeants go through the barrack-rooms urging haste. We get our breakfast soup and quickly get it down. Then at 0800 hours the older ones fall in in front of the building. We go through their ranks once more and shake the hands of this one and that. Many have their cartons of civilian clothes with them. Are they taking them off to the front? The staff sergeant comes along and we pull back. The sergeants then go through the ranks checking that their equipment is correctly fastened. Then Lieutenant Stichler arrives and Staff Sergeant Becker makes his report. The company commander makes his farewell and announces their destination: Frankfurt on the Oder. These recruits are being sent into the front line to be trained in accordance with a Führer-Order.

Orders are given. We step back and escort them as far as the barrack gate. The sun breaks through as the Russians march in singing for their training. Life goes on.

We return to our barrack-rooms, but on the way a young SS staff sergeant, whose cap is not worn regulation straight, chases us several times round the barracks. We then sit about in our barrack-rooms until about 1000 hours. A group of comrades gather round the table in our room and play cards until Staff Sergeant Becker disturbs our peace. We have to have our hair cut, but Stroschn and Boy decide to try and dodge this. I have the matchstick length of the Labour Service, but who knows when I will get another opportunity?

I put on my cap and go to the battalion headquarters, where the barber has his place in an undamaged part of the burnt-out building. I am already sitting down in front of the mirror with an apron over me when two quartermasters come in and I have to get up again and let their lordships, who receive an immediate greeting, take my place. Recruits fall into the lowest category and have to wait their turn. When I eventually emerge, it is with a real Prussian haircut.

Before lunch we receive orders to clean out a barrack-room in the East Block, whose occupants were sent off to the front several days ago leaving behind torn palliasses, upturned broken lockers and strewn bedding. The room is full of dust and we hurry to get out of the dirt. From time to time a sergeant sticks his head through the door and barks out orders. We pay no attention until he is reinforced by two other sergeants and stands in the room screaming at us. We stand to attention and listen quietly, each one thinking, ‘Go to hell!’, but adopting expressions of eager attention to duty mixed with a modicum of contriteness, until he runs out of steam. Then the three of them vanish together leaving behind in a corner several palliasses that they have ripped apart so that a cloud of dust creeps slowly through the room.

These ‘indispensable’ shirkers are all the same. The louder the mouth, the more essential they become for the barrack square, something of which they are fully aware. In the barracks there are more ‘indispensables’, clerks, orderlies, instructors and storemen rather than simple soldiers, all clinging to their roles like drowning men to the last straw, terrified of being sent to the front. Sometimes I would like to punch them in the face.

After a short lunch of dried vegetables, we have to clean out the filthy dining room, where potato peelings have been lying about for days, while in the kitchen the fat cook munches a meat ball with the fat running down his cheeks, making our mouths water.

By the time we have finished, the guard is being mounted. The Hungarians come in for a meal and shyly make way for us, but their eyes glimmer with anger, their officers only holding them back with difficulty. Poor chaps, but watch out when that volcano erupts!

Then our platoon parades for duty with gas masks and capes. We are down to 100 men now, eighty having left, but new ones are arriving all the time. A 58-year-old arrived today with one leg shorter than the other but still declared ‘fit for duty’.

New filters for our gas masks are issued by the armoury. We have already been given new eye pieces, every item being entered in our paybooks, and now we only lack weapons.

We then go to the gas chamber, which is situated outside the barrack area under some trees, and Staff Sergeant Becker releases some training gas in the chamber for us to test out our new filters. We enter the chamber in groups. Light enters the smoke-filled room through a window. The comrades go around like primeval animals, like circus ponies. We have to bend our knees, hop, turn and jump. The air soon runs out under our masks and the eye pieces mist up. My skull pounds like a drum. Then we slow down and do breathing exercises through the mask. Unscrew the filter, hold it up, screw it on again. Finally we sing, the sound muffled as from the grave.

We stumble out again with our lungs wheezing and rip our masks off. Boy has to hand his in, as it does not fit. Gradually we regain our breath, sitting on tree stumps and enjoying the sounds of nature. A bird is singing somewhere and the hum of the metropolis can be heard in the distance.

Finally the last ones come out. Even ‘The Scarecrow’ and Sergeant Rytn have taken part. When the latter removes his mask, his blond hair flutters in the wind and for a moment he looks the large child he is, but he soon resumes his duty expression. How status and some symbol of rank can change us Germans, then all the rest become puppets and must dance to our tune.

In the evening I break my spoon, and the supply clerk gives me another one in exchange for my cigarette ration. Then Boy, Stroschn, Windhurst and myself play rummy in the canteen before going to bed.

An air raid wakes us up again. A window in the battalion headquarters shines brightly in the night. Searchlight fingers reach up into the sky, Mosquitos hum, and multi-coloured ‘Christmas trees’ swing about as explosions shatter the earth. The flak fires with heavy thuds, sending their shells high into the night. When we return to our beds, red flickering fires are lightening the sky above the city centre.

Thursday 5 April 1945

After reveille the staff sergeant bursts into our room. Ten men are detailed for bomb damage clearance, but I am not one of them. During the morning the rest of us are marched to the officers’ mess for a lecture. A brand new second lieutenant, fresh from officer training school, talks about soldierly duty and obedience. I imagine this boy without his uniform. Snoring comes from a corner where Alfons has fallen asleep. We are visibly bored. Milkface has us stand up and pay attention. He stands right in front of me, the first fluff just showing on his upper lip, and can be no more than 19. After an hour he dismisses us and goes into the officers’ kitchen, from where gentle odours tempt our nostrils. Apparently our superiors get roast meat, while we only have dried vegetables.

Then we loll about our barrack-room. We have to exchange all our unsuitable items and are glad to get rid of them. Boy and myself look through the window and see two lads from the Home Defence Flak going past behind a civilian, an old man with a limp, presumably wounded in the First World War, the oafs imitating him, laughing and joking. We go down to the square and give them a piece of our minds, and when they get cheeky they get a punch on the chin and slink away like whipped puppies.

A group of chattering women with headscarves and shopping bags come from battalion headquarters, several of them with pistol belts fastened over their aprons, some SS officers walking along with them. These are Berlin housewives who are getting five hours’ shooting instruction per week in response to an appeal put out by Goebbels.

Steel helmets are issued after lunch. We are to be sworn in today, so three comrades go off to decorate the dining-room. We clean and polish our equipment, and parade at five o’clock. The staff sergeant goes through the ranks. Everyone looks the same under the steel helmets. It is the universal face of 1945, the face of youth.

We take up position in the dining room. The Reichs War Flag and the Party Flag with the swastika are hung on the panelled walls, symbols of the unity of the armed forces and the Party? Opposite there is a poor oil painting of Hitler and two machine guns on the floor with their barrels pointed towards us. An officer enters and the staff sergeant makes his report. The young second lieutenant speaks about the flag, the Führer and obedience until death. I am not with it; to me it is all like the stage of a theatre, myself a stand-in in a sad scene. He reads out the form of the oath in a dull voice and we repeat it slowly after him ‘With God’s help!’ The hands return to our trouser seams. I see red before my eyes and would like to punch him in the face. We then have to sign our names in a big book to say that we have sworn the oath.

Friday 6 April 1945

This morning the lieutenant informs us that we will be leaving for the front early tomorrow morning. Since the swearing-in ceremony we are called ‘Grenadiers’.

We begin slowly packing our things together in the barrack-room. Our peaceful time in barracks has come to an end. The staff sergeant expresses his regret that we should be leaving so early tomorrow, as another fifteen men are to be shot, ten of them from the 20 July plot.

During the morning we work on our kit until it is spotless, for the battalion commander will be taking the kit inspection. After lunch we hand in our cutlery to the supply clerk, then go back to playing cards in the barrack-room with Alfons, the former railwayman, and Erich, the ship’s cook, now ‘Grenadiers Müller and Schulze’, names symbolising our future.

Then we have to parade outside on the big barrack square in front of the war memorial. We stand well apart with our kit spread out on the ground in front of us. The battalion commander takes over the parade. ‘At ease!’ he croaks, then Staff Sergeant Becker reads out the individual items from a paybook. We have to hold up each item as the major passes through the ranks. If something is not to his satisfaction, we have to go through the whole thing again. Finally he wants to see if we are wearing the first issue set of underwear. Wegner and Ebel have to change clothes on the square after first running ten times round it in their second set. After nearly two hours of this, the major is getting hungry. In a bombastic speech he tells us it is an honour to die for Hitler so young, and about the man-eating Bolsheviks, and then extracts a ‘Sieg Heil’ from us before disappearing in the direction of the officers’ mess.

In the evening a fat paymaster, another ‘indispensable’ whose home comforts clearly show, hands out our pay. Each of us is given three RM10 notes of freshly printed ‘Himmler Money’.17

Then we all get together in the canteen. Windhorst has heard that we are leaving in the morning and has come to join us. We talk about our future prospects. In the Armed Forces Report there is mention of fighting in the west near Nuremberg and Hannover. Peace reigns behind the lines again, but there the war rages with undiminished ferocity, daily crushing new lives between its millstones, while the leadership speaks of miracle weapons in order to whip up the suffering people into the utmost destructive nonsense. After us the deluge! That is the slogan, and the youth believe in Hitler as if he were the Messiah. Me too!

The sirens break us up. In the shelter a mouth-organ plays softly while outside the flak thunders and the earth shudders from its wounds, and the bombers’ engines roar in unison as they bring death and destruction to the stricken city.

Saturday 7 April 1945

Sergeant Rytn goes through the barrack-room waking us up. Once more, and for the last time, we stretch out in our beds and then dash for the washroom. Rations for the journey, consisting of bread, sausage, butter and cigarettes, are available in the duty NCO’s room, but there is hardly any space for them left in our packs, so we decide to eat immediately anything we cannot pack, and we all chew away with our mouths full.

The clock’s minute hand moves remorselessly on, the last minutes stretching like rubber. I quickly repack again, underclothes, writing materials and a small photograph album, all that remains of my civilian existence. It is a wonder that we have been left this much, a hitch in the drive for conformity. What did the major say yesterday? ‘Thoughts of home are sentiments unworthy of a young soldier!’

Staff Sergeant Becker calls from the square. We take our things and go slowly down the stairs. The sergeants go through the ranks again. There a strap is not right, here a belt not straight. In the background are the comrades staying behind. Alfons is cracking jokes: ‘See you in the mass grave!’ ‘We’ll keep a window seat for you!’ comes back. A pity that the older ones are remaining here, for their experience could be useful in holding back the impetuous enthusiasm of us youngsters.

The lieutenant comes on the parade ground. ‘Attention!’ He quietly accepts the staff sergeant’s report, then says goodbye. A sergeant, our escorting NCO, steps forward and we march off.

The platoons are emerging from the East Block, coffee carriers are hurrying across the square, the Hungarians are marching singing to the ranges, and the fat sergeant major is detailing fatigues outside the convalescent company block. Windhorst salutes with a nod. The barrack gates swing open and we leave our comrades behind. The Russians march past singing mournfully. The barracks are behind us as the bright sun breaks out.

A new phase of our lives is about to begin.

2

Off to the Front

We are marching along to Ruhleben U-Bahn station and ever since the barracks gates closed behind us, hopefully for ever, I feel as if I have been set free. The trees along the road are covered in greenery, and the buds seem ready to burst open. We are heading into an unknown future.

Volkssturm1 with reluctant expressions are working on the construction of a barricade near the underpass. They have already ripped up the pavement and driven iron girders into the earth, and Reichsbahn2 goods wagons have been filled with stones ready to be pushed across the road should the need arise.

At the U-Bahn station we go through the barriers up to the sun-drenched platforms,3 the escorting NCO remaining below to get our movement order stamped. The train’s departure time approaches. ‘All aboard!’ We all pile into the carriages the way we did as civilians in the old days when there was no time to spare. As soldiers we should have waited, but the civilian in us is still not dead.

The doors close and we are off. As we start to move, I can see the escorting NCO running up the steps, gaping in astonishment after the departing train. On our way we discuss among ourselves what we should do about him. He has all our papers, including our paybooks, in his possession.

The carriage gradually fills up, mainly with women going shopping in the city. We get out at the Kaiserdamm and make ourselves at home on the platform. The trains roll up, stop and roll on again to vanish as small spots in the distance.

There are some magazines displayed outside a newspaper stand, and the front page of the Illustrierte Beobachter shows a smiling SS officer wearing the Oak Leaves to the Iron Cross.4

At last the escorting NCO turns up on one of the trains. He approaches us angrily but calms down when he sees that we are all here. We take the next train to the Zoo, where we leave the U-Bahn and climb up to the S Bahn station above, the traffic surging round us. The women and girls strolling along the streets have discarded their warm clothes for spring outfits. The ruins of the Memorial Church5 lie in the morning sunshine on the left. The Memorial Church, Kurfürstendamm, all are well-known names, favourite parts of Berlin that only a short time ago we were able to look at as free citizens. What a world divides them from us now when we can only catch a fleeting glimpse of them. A tram stops, cars race by. Bustle, business – the tempo of a big city!

We get up to the S-Bahn platform just as the Erkner train pulls out of the station, and now we will have to wait another twenty minutes for the next one. We put our packs down and wander up and down the platform, where SS officers with immaculate creases, in leather coats with fur collars and wearing light belts with pistol holsters, are casually smoking their cigarettes, their pig leather suitcases at their feet. Political leaders in their yellow uniforms are wearing Volkssturm armbands, and a fat man with a briefcase and wearing a swastika armband on his overcoat is blowing his cigar smoke into the air appreciatively. Girls in transparently light spring dresses, careworn women, bleary-eyed workers, and hungry children are standing around; the many faces of Berlin.

At last the name Erkner comes up on the board and the train rolls in already overfull. We push and shove to get in. The stations go by like a film strip – Friedrichstrasse with the burnt-out dome of the Wintergarten on the right, and across a desert of ruins; the Schiffbauerdamm, the Admiralspalast, and Alexanderplatz with the Berolina statue, and the Hertie and Awag department stores.

The big city’s sea of houses thins out and the countryside begins to fly by – Karlshorst, Rummelsberg, allotments with people working in their gardens, a farmer ploughing. The trees and bushes are freshly decked in greenery and the jubilant birds climb high into the blue sky.

The S-Bahn ends at Erkner and we will have to go on from there by suburban train, the next leaving in three hours’ time.

The platforms are full of activity with officers and soldiers of all arms of the services, even sailors fighting on the Oder6 waiting for their connections. There are posters everywhere warning the troops that desertion means facing court martial. There are also some women on their way to barter in the villages for food for their hungry children, and refugees from Frankfurt on the Oder wanting to go back to rescue more of their things, all sitting on baskets and sacks, while SS7 and military police check passes.

We get our paybooks and are allowed to leave the station. I leave my pack and haversack on the platform.

There are some ruined houses in front of the station and the remains of a bombed-out factory. Erkner, once a blooming suburb with hidden beauties, was transformed overnight by a sea of fire, the Kugel-Fischer ball bearing factory having brought death and destruction to this place.

There are no pubs open in Erkner. They are all filled with refugees and bombed-out residents eking out their sad existence with the remains of their belongings.

I walk slowly through the place past burnt-out weekend allotments and small family houses standing accusingly in the greenery of their gardens. I am frequently accosted about my age, and a young girl even offers me her brother’s civilian clothes and to hide me, but I lack the courage to accept.

In front of the station there is a small grassed-in area, where I spread out my greatcoat and stretch out on it. The now quite warm sunshine is comforting. I lie there dreaming and thinking of the future. A comrade wakes me. It is time to go!

There is no way of getting through on the platform. The trains from Berlin have been discharging more people at the station, most of them civilians. The train comes in and is immediately stormed by the civilians, and now I can get to my pack, which is still lying there undisturbed. Most of the comrades from our group are there. SS clear the front half of the train of civilians so that we can get on. I take a window seat and put my pack in the luggage rack. Once all the soldiers are aboard, the civilians are allowed back on and stand gratefully in the corridors, packed like sardines. Our escorting NCO is nervous as Wegner is missing, but at last he storms aboard just before the train leaves.

We chug along slowly through the countryside with the heath coming right up to the tracks on either side. Trenches and barbed wire fences in this undisturbed landscape serve to remind us of the seriousness of the times. People stand like walls at the little stations, trying to get aboard, and clumps of people are on the roofs of the carriages, on the running boards and buffers, and in the brakemen’s cabins. Some are even clinging to the pipes of the engine’s water tanks.

The train stops from time to time. Air attack alarm! Soldiers of the train guard are watching the skies from the roofs of the engine and the last carriage. Suddenly a bugle blows. Low flying aircraft! People fly out of the carriages in panic, while others jump off the roof on to those below. There is a roaring sound as the first of them reach the shelter of the woods. I lie down between the rails listening to the tacking of the machine guns over and over, and when all is quiet again, I get up. People lying in the woods and ditches timidly raise their heads and slowly begin to breathe freely again, but then comes the sound of aircraft engines and everyone vanishes again like lightning. White steam rises from the engine like candles. But these are German aircraft passing over the train and gradually the people return, fear stamped on the faces of the women and children.

There are bullet holes in the carriage and splintered wood in the compartment. Incredibly the engine is undamaged, nor have any of the people been hit. Only a few women have been hurt in the panic, and a 12-year-old has had her ribs crushed.