4,68 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

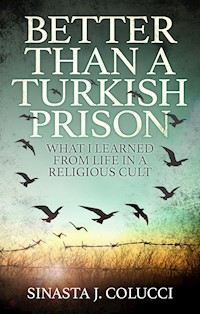

Better Than a Turkish Prison is the true story of a needy young man who encounters a religious cult known as "The Twelve Tribes". With no better options in sight, he decides to join them in their pursuit to build the kingdom of God on Earth. After years of brainwashing and servitude, he must break free from a powerful delusion in his search for freedom and truth. Not merely a deeply personal portrayal of one man's struggles, this book also serves as a critical analysis of religious ideals and their effects on humanity as the author divulges his presently held beliefs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 362

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Better Than a Turkish Prison

What I Learned from Life in a Religious Cult

Sinasta J. Colucci

Copyright © 2019 Sinasta J. Colucci

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission from the publisher.

Published by Hypatia Press in the United States in 2019

ISBN: 978-1-912701-67-4

Cover design by Claire Wood

www.hypatiapress.org

Author’s Note

The Subjective Word of Men

I want to begin by giving credit where credit is due. Much of the knowledge that I currently possess is esoteric in nature. It is the direct result of having been indoctrinated into a religious cult, known as The Twelve Tribes Communities. For nearly eight years, I was entirely immersed in their culture, hearing their teachings and learning their theology, which itself is the result of decades of councils which regularly took place between the community’s most intelligent men and rarely women (sometimes women contributed to these councils, but men were ultimately the leaders). These councils aimed to interpret the Holy Bible, and apply it to the community, using it to dictate the lives of each individual member of the cult. They also studied religious history and used it to strengthen their narrative. Though I am now my own man, free from this cult’s authority, I feel it is only fair to acknowledge that this book would not have been possible without them.

Whether one believes the Bible is the inerrant word of God or not, the fact remains that it is a beautiful work of literature that has a way of leaving its mark on people. It is filled with poetry, wit, humor, sarcasm, and historical significance. I would recommend it to anybody who has even the slightest interest in religion or world history, as there is a great deal that can be learned from what is written in the various books of the Bible.

Having said that, there are a few misconceptions that should be understood before you can fully understand these works:

First off, it is not one book, but a collection of 66 different books, written by about 40 different authors1. Consider this when reading Revelation 22:19.

“…and if anyone takes away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God will take away his part from the tree of life and from the holy city, which are written in this book.”

Was this a warning for anyone who takes away from the words of the Bible? The whole Bible? All 66 books? Remember, it wasn’t one concise book at the time John wrote the book of Revelation, but rather, there were many different books, which were considered holy. So, it is not likely that John knew he was writing the last book of the Bible when he penned these words in Revelation.

People like to quote the Bible in ‘Olde’ English, but the most recent book of the Bible was completed at least about 500 years (and at most, about 1,000 years) before the English language was created.2,3 The original Bible (referring to all 66 books, both old and new testaments) was written in three different languages: Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.4 Having a basic understanding of these languages is part of the key to understanding the Bible. The hard ‘J’ sound did not exist in any of these languages. The first book to make a distinction between the letter ‘J’ and the letter ‘I’ in the English language was Charles Butler’s English Grammar, written in 1633. This was about 22 years after the King James version of the Bible was completed, and over 100 years after William Tyndale translated the New Testament and part of the Old Testament into English.5 So then where does the name ‘Jesus’ come from? Think about this as you read Acts 4:12.

“Salvation is found in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given to mankind by which we must be saved.”

We’ll revisit the subject of language and of the Savior’s name later. I use it as an example here because it is important to note before reading the Bible in the English language, that you are not reading one book in its original form, but one that has been modified throughout history. The Bible is made up of multiple books, written by multiple authors, being displayed in a language other than the language they were originally written in. I would also advise that you do not read it as if it were “the objective word of God”, as many denominations of Christianity would have you do. It would more accurately be described as “the subjective word of men.” While it has great historical significance, I do not view the Bible as a history book, nor a moral guide book, but rather as a collection of stories, concepts, and poems, which can help us gain an understanding of the men who wrote it, and the times they were living in.

By now, you may have guessed that I am an atheist, which was the second most negatively perceived religious group in America following Muslims, according to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey. The difference between the two groups was only two points on a scale of 1-100. Jews took the number one spot for the most positively perceived group with 67 points, followed by Catholics with 66, Mainline Protestants with 65 and Evangelical Christians with 61. Atheists scored 50 points and Muslims with the lowest score of 48. No religious group received a perfect score of 100.6

I currently reside in Central Lake, Michigan. The overwhelming majority of Central Lake’s residents are Christian. To be clear, I do not hate people based on their religious affiliation, so if you ask me if I hate Christians, I’ll tell you, unequivocally, that I do not. In fact, there have been many people who have helped me during difficult times in my life who were likely motivated by their Christian faith. Much of what I have to say about the religion and its bloody history is unrelated to my opinion of Christians in general, and is especially unrelated to modern Christians. Since most of my daily interactions are with Christians, I am often asked, when the subject comes up, why I became an atheist. Some might ask that question hoping to perform their godly duties of converting me, but I think a lot of people have a genuine curiosity, and some are legitimately concerned for my soul. I do not get offended by this, as many atheists do. I see this as a natural human inclination towards compassion. However misplaced that compassion may be, it is still legitimate and we atheists should recognize and appreciate that before we respond to such inquiries. That way we will (hopefully) respond appropriately. Whatever the motive for asking it, the question of how I became an atheist is never easy to answer. This is not only due to the personal nature of such a question, but it would also be impossible for me to give a complete answer. Even so, this book is an attempt to do just that.

Contents

1.Anything but Godly

2. Torn

3.A Blossoming Myrtle Tree

4.Abra-Cham

5.A Farmer’s Destiny

6.A Young Sprout in a Rocky Place

7. Controlling my own Destiny

8. Culture, Racism, and Personal Preference

9. The Size of the Universe

10. Religion Versus Morality

11.I am a Believer!

1

Anything but Godly

To be fair, I didn’t start off as a Christian. I had no religious affiliation growing up, so the question of how I “became” an atheist isn’t about how I fell away from the Christian faith, so much as how I learned about Christianity in the first place, and how my current position as an atheist has become so solidified. I was born in Detroit, MI in 1984. My father is very religious and always has been. He describes himself as a “Rasta man,” rather than a “Rastafarian.” His religion is uniquely his and seems to stem from his upbringing as a Jehovah’s Witness, with a blend of Rastafarianism, an apocalyptic outlook on life, and a deep-seeded narcissism that causes him to imagine himself as the king of the biblical tribe of Benjamin. My father didn’t raise me though. I didn’t learn all this about him until after I met him at the age of 19. I was raised by my mother, who could best be described as a free-spirited hippie.

In 1984, Detroit, MI was a large and rapidly shrinking city and Redding, CA was a small town that was growing fast. My entire family was from Detroit, but two of my uncles, who were carpenters, found work in Redding and my mother decided to follow them out there, along with my five-year-old sister and me. I was only three months old at the time. My mother says that her decision to move us out to California was motivated by a desire for us to grow up in a safe and healthy environment. I’ve asked my father why he decided to stay in Detroit instead of coming with us to Redding, and he told me this story about how my mom threatened to call the Shasta County Sheriff’s Department on him if he tried to follow us out there, and how they were racist and would have shot him if he’d have shown up. Apparently moving to Redding wasn’t only about our health and safety. By the time my mother made this decision, she had already decided she wanted to be far away from my father and to never see him again. To this day, she never has. I wonder: If my mother actually thought the officers in Redding were really so racist that they would have shot a black man on the spot, just for showing up at someone’s door, how safe did she think we’d be there (me being mixed-race)? Sadly, she’s almost entirely senile now. She is also suffering with Huntington’s disease. For these reasons, I cannot understand most of what she says, otherwise I would ask her.

Indeed, racism did play a major role in my upbringing. I couldn’t have been much older than four years old when my mother taught me about Nazis and the KKK, and how they would kill people who have skin like mine. I used to have nightmares about it, and even experienced a few hallucinations. I have sickle cell anemia, and would often experience intense pain. Until I was diagnosed, at the age of eight, nobody knew the reason for this pain, and I did not receive any medication for it, so when it became particularly severe, I would hallucinate. On one such occasion, late at night, I thought I saw a man wearing a white Klan hood, glaring at me through the window from outside. At a very young age, when I was still in preschool, I was consciously aware of my being different from all the other kids. Redding is primarily white, and was probably more so back in the late 1980’s. I don’t remember being made fun of or mistreated at such an early age, but I do remember an incident where I decided to scrape my arms vigorously with some tree bark hoping to make my skin look whiter. My mother, who also happened to be a teacher at the preschool I went to, came up to me and asked me what I was doing. When I told her, she sat down on the ground with me and spoke to me about how I should be proud of my “Native American heritage.”

If you’re a little confused right now as to what my actual heritage is, that’s totally fine. I was a thoroughly confused child. I’m a mix of African, various European nationalities, and Cherokee. My full name is Sinasta Joseph Ukiah Colucci, but my mom just called me “Ki.” From what I’ve heard, both of my parents named me, and they wanted me to be proud of my Native American heritage in particular, so that is where the names ‘Sinasta’ and ‘Ukiah’ came from. Both are Cherokee.

I spent a large portion of my childhood thinking that my dark skin was a result of my Native American heritage, and I wasn’t taught much about my African American heritage. I was enrolled in Indian Education when I was in the fourth grade. I had been held back from kindergarten until I was six years old, so I would have been ten years old when I started fourth grade. Therefore, it would have been the fall of 1994 when I witnessed actual racism from the Shasta County Sheriff’s Department.

As of this writing, it has been 23 years since this incident occurred. It is important to keep that in mind before judging the present-day Shasta County Sheriff’s Department. The history of relations between the local Native American tribes of Shasta County and the white settlers goes back to the 1800s. The Winnemem Wintu Tribe had been recognized by the federal government since 1851, but as of 1985 they were no longer recognized as a tribe. They had to relinquish much of their land with a treaty in 1851 and were confined to a small area along the Sacramento River Valley. They were “relocated” when the Shasta Dam was built in 1985. Everything the Winnemem tribe had was bulldozed, then flooded, with the creation of Lake Shasta. Since they were no longer federally recognized, they could not receive any assistance from the government, and the land that had been allotted to them prior to 1985 was taken from them. This and many other tragedies, such as disease, depletion of resources, and intentional poisonings, caused the natives of Shasta County to develop some resentment towards the European American settlers.

In the fall of 1994, while enrolled in the Indian Education program, I had marched in a parade which ended at the local middle school, where I delivered a speech. Afterwards, I met up with some friends from the program and we went to the park across the street. We were playing at the playground when we saw a fight break out between a white man and a Native. Both were clearly drunk. Soon after the fight started, two squad cars pulled up. A female officer and three male officers jumped out and quickly broke up the fight. They handcuffed the Native man and let the white guy go. We watched as he staggered across the park. Once handcuffed, the Native was thrown face-down on the concrete. A couple of the male officers beat him in the back with their clubs and the female officer pulled his head back by his hair and emptied a can of pepper spray in his face. They threw him in the back of one of their cars and drove off.

I was stunned by this event, and from that time on I had been deathly afraid of being beaten or killed because of how I look. I couldn’t think of any explanation for what happened other than blatant racism. All four officers were white. The white guy, from what my friends and I could see, was just as guilty as the Native. In hindsight, I realize that there could have been other factors. Perhaps the Native had a warrant out for his arrest and the white guy had no priors. But then again, why would they let him just walk off? They had two cars. Could they not have given him a ride home in one of them rather than have him walk through a park full of children in his agitated and intoxicated state? It just doesn’t add up. Regardless of why it went down the way it did, that incident had a significant effect on my outlook on life, and even affected how I perceive religion. Put simply, it just wasn’t fair.

For the most part, I did have a peaceful upbringing. I was called names a few times, from people who couldn’t figure out what race I was. I was called “Sand Nigger,” which I guess is supposed to be a slur against Arabs. Some called me “Wetback” or “Beaner”—slang for Mexican. And a few times I was called “Nigger” or simply “dirty half-breed.” People couldn’t figure it out, but they knew for sure they didn’t like my skin color. I grew paranoid that everybody in Redding hated me and that it was just a matter of time before a mob of angry white people decided to grab me and hang me on a tree. Fortunately, I was never physically attacked.

In high school, I used to get into political arguments with people. I don’t recall ever having a religious debate. It was usually political in nature, because most of the students were conservative-leaning and I was liberal. The only incident I can remember that got out of hand was in a geometry class. I’m pretty sure the teacher was just lazy and really didn’t give a fuck, or maybe he agreed with the students, but either way, it got way out of hand. Some of the students in that class thought I was gay, so they used to mock me quite a bit. I never told them I wasn’t gay, because I didn’t think that should matter. In my mind, they shouldn’t have been treating me badly if I was gay, so why should I have told them I was straight? One time, as we were having one of these arguments, one of the guys came up behind me and pulled my pants down, boxers and all, while I was standing in front of the entire class. I quickly pulled them back up, but one of the girls in the class made a comment about the size of my (flaccid) penis, and they all proceeded to laugh and mock me for it. To this day, I still don’t know how to calculate the area of an isosceles triangle, but I do know that I don’t like gay bashers!

It was also in high school that I picked up my first Bible. Someone was handing these little Bibles out in front of the school. It was this little, orange-covered book. It had the New Testament, Psalms, and Proverbs. I used to read it at night. I wasn’t sure what my mom would think about it, so I didn’t tell her. I remember one time, it was like this miniature religious experience. I was reading my little Bible with a flashlight, and the light suddenly went out. I prayed, and it came back on! Miraculous! Since then I’ve had plenty of experiences with cheap flashlights that have loose batteries inside. The light will go out, but all it takes is to jiggle it a little and it comes back on. But at the time I was pretty impressed by this miracle and I thanked Jesus, even though I had never been to church and didn’t really know who Jesus was or most of what he said, or actually stood for. I knew very little of religion in general at that time.

As a teenager in the late nineties, I was fascinated with end-times prophecy. There was a lot of talk about the end of the world around the turn of the millennium, and I had picked up this book about Nostradamus. There were plenty of these books written in the nineties with all sorts of theories about what exactly would take place based on Nostradamus’ writings. The one I read theorized that a comet would appear in the sky during the solar eclipse of August 1999, and that it would cause a global panic. This comet was supposed to appear as big as the sun in the sky, but it wouldn’t directly hit the earth. Instead, the earth would pass through the comet’s tail, which would result in an onslaught of large meteors. These impacts would bring about a chain of events that would lead to World War III, the battle of Armageddon, and ultimately the return of Jesus. So, naturally there were plenty of biblical references in this book and it put enough fear in me to want to be one of God’s chosen ones so that I wouldn’t have to burn in hell for eternity.

I had become so obsessed with end-times prophecy, and so drawn to Christianity because of it, that at one point I even worked up enough nerve to ask my mother if we could go to church. She obliged and drove me to a Catholic church on the other side of town (we passed plenty of other churches along the way, but for some reason she decided to drive to the Catholic church). As she drove up the long driveway and pulled into the packed parking lot, I noticed the people getting out of their cars and walking towards the church’s large double doors and I saw a lot of kids from school that I didn’t get along with. I’m not sure why I didn’t expect that, as if the church would only have godly parishioners that I somehow had never encountered before—people that were agreeable and wouldn’t fight with you, call you gay, and pull down your pants. But no, it wasn’t saints that I saw going into that church. It was the same people who I’d see the rest of the week, acting anything but godly. My mother asked me if I still wanted to go in and I said, “no” and we drove back home. I’m thinking she might have been relieved. Knowing her, she probably agreed to drive me to a church, because she felt guilty about keeping me from choosing whichever religion I wanted to follow, but I’m sure she had no desire to go into that church.

I left Redding at the age of eighteen. I haven’t been back since. I was invited to move in with an old family friend in Ann Arbor, MI. I had been friends with her son, who was the same age as me. I’d see him whenever we would visit our relatives in Detroit, and they’d come visit us in California sometimes. I accepted the invitation to live with them and completed my final year of high school there. There’s a lot I could say about that year in Ann Arbor. What I took away from my experiences there, more than anything, is that it feels better to work and provide for yourself than it does to mooch off other people. It was also during this time that I got to see the stark contrast between how wealthy and poor people live in America. Growing up, I had very little interaction with wealthy people. When I moved to Ann Arbor, I was still poor, but a lot of the new friends I made were rich. I had been invited to stay at one guy’s house a few times and it was the biggest house I’d ever seen, let alone stayed the night in. It was a bit of a surreal experience for me, because at the time I was living out of a suitcase.

The family friend I stayed with ended up getting evicted a few months after I moved in. She was a high school teacher in her fifties. She had lived in the same apartment for nineteen years, but was considering buying a house. When it came time for her to pay the lease for the next six months in her apartment, she decided not to, because she was expecting to use that money for the down payment on her new house. Unfortunately, she was not able to get the house on time (I think a few deals had fallen through at the last moment) and we ended up having to move in with her friends. Her son had left for Europe to study abroad, so it was just the two of us, moving from one friend’s house to another each week in an attempt to avoid overstaying our welcome. I don’t think it worked though. I got the sense that people just wondered why I was there in the first place and it was just awkward feeling like such a moocher. I spent a lot of time looking for work after school, but I also looked like I was twelve, and no one wanted to hire a twelve-year-old.

As soon as I graduated, I was eager to find work. My sister was living in Northern Michigan at the time. My sister had a different father than me, but we have the same mother and we grew up together. Her father, Dan, owned a farm in Northern Michigan and she’d go stay with him from time to time. At this time, she had a job at a resort there and she mentioned to me that they were hiring. She offered for me to stay with her at her father’s house and said I could work through the summer at the resort. It sounded like a good idea to me, so I went with her (much to the relief of the generous folks in Ann Arbor).

My plan was to work through the summer, save up some money, and then start college in the fall. I wanted to be a history teacher, because I’d always been good at history in school. I figured financial aid would cover tuition and I’d be fine. Well, I did end up getting a job at the resort shortly after moving up north with my sister. It was a night shift job, washing dishes. I’d ride my bike to and from work and during the day I’d take care of the farm animals. Dan also had two younger kids, so I’d take care of them too. I was tired all the time, but it was rewarding to feel like I was contributing to the household after the year I’d just had, feeling like a moocher all the time.

Another thing about Dan (my sister’s dad), was that he was a potter. He was a passionate artist. He’d teach contra dancing and would also exhibit his pottery at local fairs. Dan had a very exuberant personality and was a bit of a local hero. So, it wasn’t surprising when a few artists from Detroit sought him out to get some inspiration. They’d certainly come to the right place, because Dan was an inspiring man! The three artists were Charles, Kwame, and Ras Kente. Charles was a painter, Kwame was a sculptor, and Ras Kente was a musician, who had apparently had a few jam sessions with some very famous people. They all came to see Dan while I was still staying with him. We treated them to all the sights. Dan took them out on his boat, and I cooked a nice butterflied coconut shrimp meal for everybody. I always enjoyed cooking and even considered culinary school. I don’t recall what the side dishes were, but they must have been good, because the meal had apparently made an impression.

The three artists left after one week, but they said they’d be back soon. When they got back down to Detroit, they met up with their friend, who was going by the name of “Joshua” at the time. They started telling him about their time up north, about Dan and his farm, and Joshua told them that Dan sounded familiar, like someone he’d met before. Then they told Joshua about me and my cooking. I was going by the name “Ukiah,” and as soon as they said it, Joshua apparently took on this really intense look and started shaking. He said, “Ukiah? That’s my son!”

Meanwhile, I was pushing myself pretty hard that summer, doing much more physical activity than I had been used to. When we had taken the artists out on Dan’s boat, we all went swimming, but this wasn’t a good idea with my condition. When you jump into cold water on a hot day, your blood vessels constrict. When you have sickle cell anemia, the sickle-shaped cells get trapped in your capillaries when your blood vessels constrict, causing what doctors call a “pain crisis.” I ended up with severe chest pain, but I kept going to work. I continued to haul five-gallon buckets of water to the horses and cows, rode my bike to and from work every night, working eight-hour shifts, until the pain reached an uncontrollable point. Then I had a nightmare of a shift.

I didn’t have any prescription medications at this time, so I took a handful of ibuprofen, which doesn’t do anything for sickle cell pain, so I kept taking more. When I showed up for work, the restaurant, including the banquet hall, was packed. Also, none of the other dishwashers had shown up. There would normally be three of us working. I remember being far behind schedule, just starting on the cooking dishes when I should have normally been clocking out, but I felt like I needed to keep going. I also remember that every time I’d have to lift the baking pans up onto the racks to dry, it felt like my chest was ripping open. I was just finishing up with the pots and pans when the day crew, who I had never met before, showed up and started cooking. They kept bringing more dirty dishes to me and I didn’t know when I could stop. Finally, the day crew manager came to me and told me I should probably just go home. I rode my bike home, laid down for a couple hours, and then Dan’s wife asked me to watch the kids and take care of the animals. Looking back, I don’t know why I kept going and did all my chores that day, but it wasn’t until mid-day that I finally admitted that I needed to go to the hospital. I didn’t show up for my dishwashing job again.

It was only about two weeks before I was to start college in Detroit. I had been bedridden for eight days at the hospital in Traverse City. Shortly after my release from the hospital, those three artists came back up for an art fair and they told us about my father. They also offered me a ride back down to Detroit with them and I accepted. I had stayed the night at Ras Kente’s house, and the next morning he handed me his phone and said I had a call. When I picked up the phone and said, “Hello,” my dad started talking. He didn’t stop for about another hour. It was an odd experience listening to him though, because he was a stranger to me, and yet it was like listening to my own voice. He had attempted to defend himself for not having been a part of my life, telling me his side of the story of what had transpired between him and my mother 20 years prior.

My father came and picked me up from Ras Kente’s house in Highland Park and brought me to his place on the east side of Detroit. He said it had been “really mystical” the way we had been brought together. He said that when he was with my mother, she took him to meet Dan. He remembered riding one of Dan’s horses. Dan later told me the same story, about seeing this “huge, muscular black man with long, flowing dreadlocks, riding an Arabian horse—bareback, and at a full gallop.” Indeed, it was an interesting coincidence that I met my own father through my sister’s father, and that the two had only met once before.

I stayed with my father for a few days. Like me, he too was obsessed with the end of the world. He told me his own apocalyptic visions and predictions for the future. My father was convinced that the world, as we knew it, would come to a violent end in the year 2012. But he also thought that the Messiah would come back at that time and setup a kingdom on Earth and would appoint kings to rule over each of the tribes of Israel (my father was to be the king of the tribe of Benjamin). As improbable as it all sounds (especially looking back, now that 2012 has come and gone), I believed most of what he told me. He also mentioned at one point, that he felt like “a commune where they grow their own food would be a safe place to be.”

After spending a few days with my father, he gave me a little cash (he grew and sold marijuana for a living), and he helped me move into my dorm room at Wayne State University. As it turns out, my plan of having college paid for by financial aid and becoming a history teacher was not as solid as I thought. I was able to get tuition and some of my living expenses paid for by a grant and a loan that I had taken out, but it was the dorm’s mandatory meal program that really did me in (that and my lack of motivation). The meal program was really expensive, and I was automatically enrolled in it. I couldn’t pay for it, and eventually I was kicked off the meal program, which meant that I still had to pay for it, but I could no longer eat in the cafeteria. At that point, rather than ask for help, I just decided not to eat (I was a very proud individual back then).

On occasion, my mother would mail me some money and my father would also help from time to time. I would spend their money on food, but I would go out to eat, since I was not allowed to cook in the dorm room and was apparently not smart enough to shop for inexpensive food that didn’t need to be cooked. I was somehow able to get through the first semester of college. That winter, in February, right before the Super Bowl, I had gone a couple days without eating. Then my aunt invited me to watch the game with my cousins (her sons). That weekend I feasted on all sorts of high-fat, delicious junkiness! The next week I had another sickle cell crisis.

I called my father and he brought me to his house. He fed me meals which consisted primarily of leafy green vegetables and beans, or tofu, which is also beans, but fermented. He gave me a joint to smoke for my pain. He said it was medicinal. Unfortunately, it did not work. After a few days spent in agony on my father’s couch (not because of the food, but because of the pain), I asked to see a doctor. “Doctors are wicked people!”, he proclaimed. “What are they going to do to help you?”

I said, “Well, the first thing they’re going to do is draw my blood.”

“Drawing blood is wicked!” he said. “They’re like vampires!”

Eventually he did drop me off at a clinic near the university campus and drove off. The sign on the door of the clinic read, “By appointment only.” There was a hospital nearby, but I didn’t want to go to the ER, so I ended up walking the 5 blocks in the cold, back to my dorm room. Later that night I called my aunt. She was very concerned and said that I should go to a hospital. I told her I didn’t want to and that the pain was mostly in my legs (I had also been experiencing a lot of pain in my gut). “What am I going to do, tell them my legs are hurting?” I asked. “No, you have sickle cell, and that’s what you need to tell them,” was her response. She drove me to a hospital, and as it turned out, I was not only experiencing a sickle cell crisis, but also a gallbladder infection.

After this incident, my family (on my mother’s side) became very concerned. They provided me with an electric kettle for hot water and a box of ramen and instant oatmeal. My grandmother told me that I needed to get a job, even if it was at a fast food restaurant. I ended up working at the nearby Church’s Chicken. I increasingly picked up more hours at work and started missing classes and generally losing interest in college. Eventually, I reasoned that work is more important, because what’s the point of going to class if I’m not eating? That’s when I dropped out of school and found an apartment a few blocks away.

In hindsight, I feel like I had been ill-prepared for adult life. I remember a meeting I’d had in high school with a guidance counselor and my mother. My grades were really good at that time, and they were trying to convince me to go to college straight out of high school. I didn’t really know what I’d do, but I thought I should just work for a few years. Maybe I’d be a cook or a farmer. They hated that idea, but looking back, it would have been smarter.

I learned a few things working as a cashier at Church’s Chicken in Midtown Detroit. People in that city are generally angry, especially when they are hungry and in a hurry. I also realized that white people aren’t the only people that can be racist. In Redding, people called me “nigger,” but in Detroit, they called me “white boy.” I started noticing trends in the people that treated me badly, as opposed to the people who were friendly. It seemed like when I’d get cussed out, it was usually by black women, and whenever a white man would come in, it seemed like he’d be overly friendly. This ran counter to my previous prejudices, and it served as somewhat of an anti-prejudice, visual association exposure therapy, similar to the Implicit Association Test, where you are shown images of people and your neural responses are tested.

During this time, I made a lot of friends. There were about a dozen or so homeless people between the Church’s Chicken and my apartment. When I’d work the night shift, my manager would have me throw out whatever food was left over from the day. I didn’t like this very much, so instead of throwing it all away, I’d wait till he’d go into his office to count the cash and I’d open the drive-through window. All the homeless people would line up and I’d dish out the left overs for them. This became a nightly ritual and it wasn’t long before they all knew me by name. Every once in a while, my manager would come out of his office and start yelling at me in a thick Bangladeshi accent, that he didn’t want me giving away food, because it would just attract more of “them”. Then he’d go back into his office and I’d go back to handing out the food. I didn’t care much, because I knew he wouldn’t fire me and I didn’t like the job anyway. I hated waste, and I hated the thought of people going to bed hungry while I was throwing food away. I just couldn’t do that. So, it made me feel good to do it, but another benefit was that I always felt safe walking home, late at night, in the middle of Detroit. Most of the people I passed on my walk home were the same people I’d given food to, and they’d often stop and start chatting with me about random things. One older gentleman liked to give me financial advice. One time he even stopped me in front of the college campus and proceeded to advise, in a very loud and booming voice, that I sell women’s panties on eBay. He was certain I’d make a lot of money. I never did take his advice, and not just because he was homeless, more so because I never felt like selling panties on eBay was what I wanted to do with my life.

I quit my job after one year. My health issues played a role, as well as my dislike of having to be friendly to mean people, and the fact that I wasn’t payed enough for it to be worth the hassle (at that time, minimum wage was $5.15 per hour and I was making $5.50 per hour). Unfortunately, things got worse once I quit my job and I increasingly became more desperate. That’s when I remembered what my father had told me and I searched online for “a commune where they grow their own food.” I found out that so-called “intentional communities” are all over the place, especially in America where there is a lot of religious freedom, and most of these communities are religious in nature. There’s also a program called WWOOF, which stands for Willing Workers on Organic Farms. It lists farms that participate in the program and connects people who are willing to work in exchange for experience and room and board with organic farmers who need extra help. It was through this program that I found out about the Stepping Stone Farm, in Weaubleau, Missouri.

2

Torn

As it turned out, the Stepping Stone Farm was one of several communities all over the world that are owned and operated by a cult that is known as “The Twelve Tribes.” They usually just call themselves “the community,” and they call everything outside the community, “the world.” After a couple emails and phone calls to various members of the community, I found myself at the Springfield, MO bus station, getting picked up in an old van by a long-haired, bearded guy by the name of Daveed. He had a big, creepy smile and his greyish-black hair was tied back in a fist-length ponytail. It was later revealed to me that this hair style was not only worn by all the male members of the community, but it also had historical and biblical significance. The following is a direct quote from the Twelve Tribes’ website:

“Our men have beards because men were created with facial hair. It is normal and natural for a man to have a beard. Besides, it is not fitting for a priest to crop his hair or to grow long, effeminate locks. In ancient Israel both unbound hair and a shaved head were public signs of mourning or some uncleanness. It is priestly for a man to bind his hair at the back of the neck and keep it trimmed as indicated in Ezekiel 44:20: ‘They shall not shave their heads nor let their hair hang loose, but they shall keep their hair trimmed.’ Priests are concerned about pleasing their Creator rather than chasing after the latest fashions.”

I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t a little bit nervous, leaving Springfield in this stranger’s van and heading down this rural Missouri road with nothing but cow fields as far as I could see. It didn’t help me feel any more settled when Daveed said, raising his eyebrows and still smiling that creepy smile, “We’ve made a covenant… to die