16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Under the blazing Iraqi sun in the summer of 2007, Shannon Meehan, a lieutenant in the U.S. Army, ordered a strike that would take the lives of innocent Iraqi civilians. He thought he was doing the right thing. He thought he was protecting his men. He thought that he would only kill the enemy, but in the ruins of the strike, he discovers his mistake and uncovers a tragedy.

For most of his deployment in Iraq, Lt. Meehan felt that he had been made for a life in the military. A tank commander, he worked in the violent Diyala Province, successfully fighting the insurgency by various Sunni and Shia factions. He was celebrated by his senior officers and decorated with medals. But when the U.S. surge to retake Iraq in 2006 and 2007 finally pushed into Baqubah, a town virtually entirely controlled by al Qaida, Meehan would make the decision that would change his life.

This is the true story of one soldier's attempt to reconcile what he has done with what he felt he had to do. Stark and devastating, it recounts first-hand the reality of a new type of warfare that remains largely unspoken and forgotten on the frontlines of Iraq.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 439

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

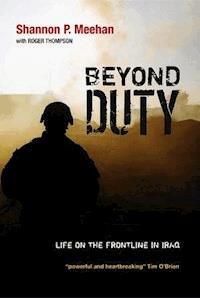

BEYOND DUTY

For AJand those who have fought and those who have fallenin the First Battalion, Twelfth Cavalry Regiment of theFirst Cavalry Division

BEYOND DUTY

LIFE ON THEFRONTLINE IN IRAQ

SHANNON P. MEEHAN

WITH ROGER THOMPSON

polity

Copyright © Shannon P. Meehan and Roger Thompson, 2009

The rights of Shannon P. Meehan and Roger Thompson to be identifiedas Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UKCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2009 by Polity Press

Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for thepurpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may bereproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or byany means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-4672-5

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 10.75 on 14 pt Adobe Jansonby Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, CheshirePrinted and bound in the United States by Maple-Vail

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Author’s Note

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Epilogue

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Polity staff and editors, in particular John B. Thompson, who provided strong guidance and a clear sense of vision for the project, and Sarah Lambert, who worked so hard to make the book possible. We are grateful to Justin Dyer and Marianne Rutter for helping move this book forward, and we thank Jeremy Clement, who made the connection that ultimately led to this project and enthusiastically supported it from the beginning. We also thank the peer reviewers of the book, whose thoughtful commentary helped us shape its final version.

Shannon P. Meehan – Deepest gratitude to Roger Thompson: with me from the start, we saw our vision through. I am blessed to have undergone such a project with you, and I am thankful for your wife Laura Ter Poorten’s considerate manner as well as her insight with the text.

This book would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of Steven Roberts, Charles Armstead (Sgt. 1st Class); Brandon Duvall, Hugo Garnica, Marion Deboe (Sgt.); Robert Smith, James Szabota, Robert Steffen, Serge Kavenaught, Jerry Tkel, Joshua Rudicil (Spc.); Isaac Warner, Chad Vos (Pfc.); and my entire platoon, Wolf Pack, of Delta Company. This includes Cpt. Paul Carlock, whose guidance and mentoring friendship will forever be appreciated. To Lt. Col. Morris T. Goins, leader of The Chargers, whose steadfast courage in the gravest of times enabled us to accomplish the unimaginable. Also, to my great friends and fellow leaders Luke Miller, Josh Southworth (Cpt.); Nicholas Poppen, David Nguyen (1st Lt.); Hollie Clevenger (Sgt.); and all those in 1-12 Cavalry who worked with me in support of the mission. Your tremendous effort and commitment to the mission made such a story possible.

I would like to thank all my former coaches, teachers, and professors at Drexel Hill Raiders, Upper Darby High School, and Virginia Military Institute, for helping to shape the direction of my life, and for all of their insightful stories and advice that I will always remember. Thank you.

I wish to express my tremendous gratitude to AJ, the wife I left behind while serving our nation. I am forever indebted to you for enduring a treacherous fifteen months alone, left to bear the burden of daily life never knowing what my future would be, and for caring for our families with complete understanding and compassion. I love you with all of my heart.

Thank you to all of the doctors and nurses who treated me at Fort Hood. From the neurology department to orthopedics and physical rehabilitation; I will always remember the care and concern with which I was treated.

For all in my family before me who willingly served our country proud, including Ed Williams (Air Force); William Henry, Larry Lynn, my father Louis Meehan (Army); Pete Hock, Ed LeSage, Eddie LeSage, Tommy Lynn, Tom Reynolds (Marines); Buzzy Lynn, Louis Joseph Meehan, Steve Phipps, and Paul Weinberger (Navy). For all their stories untold.

Roger Thompson – I would like to thank the many people who saw versions of the manuscript and provided suggestions and encouragement, among them the HIU Crew, David Rachels, Bonnie Watkins, Brian and Phil Watkins, Mary Russell, Tim Riemann, Thane Keller, Peter Cook, and J.J. Cromer. I would also like to thank both the Virginia Military Institute Ski Team (for their patience and enthusiasm as I worked throughout many of our weekends together) and the staff of the Palms (for providing me with a quiet afternoon space for working through the final revisions of the book). I thank my Department and VMI for their ongoing support of my work, and Rika Welsh for providing such a great space for writing during my time in Cambridge. To my family and the Ter Poortens, I offer my sincere thanks for your interest in and support for the book and for the many suggestions for how to think through some of it. It means a lot to me.

I want to express my deepest thanks to Laura, who sacrificed much. I so deeply appreciate not only your thoughtful readings of the manuscript, but also your understanding and patience during some of the intense periods of writing that took me away from home. I know it was a lot to ask during difficult times. Finally, I want to thank AJ and Shannon for their willingness to talk so openly about their lives and to share their story. I hope we have honored your experience, and I hope we have made a difference.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Beyond Duty is a work of nonfiction. All events included in the text took place and have been retold to the best of my memory and with the help of several others involved in the events. Names of Iraqi citizens and U.S. fallen soldiers, as well as many routes and roads, have been changed within the text. Conversations presented in dialogue form have been re-created from my memory with the intention of appealing to the core of what was said, not to represent a verbatim account.

Diyala Province

Area of Operations

PROLOGUE

The day that I served as Company Commander, I painted my helmet gold. The sun blazed with a temperature of 124 degrees, and my men teased me, laughing at the gleaming helmet. Even so, when I crawled into my tank with my fellow soldiers, my friends, we all took a moment to recognize the fact that today was different. Today, I was commanding them in battle.

I was a platoon leader, but when my Company Commander had returned to base to refuel his vehicle, he appointed me to lead the company while he was gone. Our orders were to shut down Baqubah, a shattered city now more dead than alive, and clear insurgents and Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) from a section west of Route Highlands, a major north–south artery running through the city. We arrived in tanks, Bradleys, and Strykers. The tanks were both heavily armored and heavily armed, and they were able to protect the men in ways that Bradleys and Strykers could not. The last Bradley to see action before our mission was burned to a skeletal frame by a large IED, and al-Qaida had given Strykers a particularly bloody reception to the city. Within hours of their first patrol through Baqubah, two Strykers were catastrophically destroyed. One was cut in half, and the other was flipped in an explosion. Our soldiers died in both. Tanks, then, were the best option for battle, but we needed the Strykers and Bradleys to transport the men.

As our company rumbled into position, I maneuvered my tank southeast to the intersection of Route Highlands and Route LeBarge, an east–west road. The company fanned out northward, each platoon assigned to a different street. I directed the company’s movements from my tank, and my job was to support my men when they faced resistance. Within minutes of our mission beginning, it was clear it was going to be a difficult day.

The men were encountering a new IED every few yards, making their movement painstakingly slow. More distressingly, however, one of the platoons had, shortly after our arrival, been engaged by an al-Qaida Rocket-Propelled Grenade (RPG) team. The enemy had waited on a rooftop, and they fired on my soldiers. All I heard was an explosion echoing through my earpiece and one soldier shouting, “Contact RPG team! Southwest!” I heard Blue Platoon open fire from their Bradley armored vehicle with a 7.62 machine-gun, streaming bullets through the air. Then I heard them unleash their more powerful 25-mm cannon. The force of their response demonstrated to me they were under heavy threat. I could hear the enemy continue to fire RPGs and their AK-47 rifles, and I got the report that two of my men had been slightly wounded in the initial attack, one with a broken nose and one with a separated shoulder. When it was clear that the cannon would not be enough to suppress the RPG team, they called me for support.

I asked them for as much information as they could provide. I needed to know the exact makeup of the enemy, the exact location of the building with clear and accurate coordinates on our grid, and the full nature of the injuries of my soldiers. The radio vibrated with updates, but gunfire drowned out their reports. The platoon leader’s commands mingled with the sound of the cannon, and, in pieces, details filtered back. Finally, above the confusion, I heard the information I most needed. I heard the grid coordinates. I called for our best option, our best weapon. I called in a missile strike.

The insurgents have no defense against our missiles, but ordering them requires certainty. I had to be sure that the enemy was substantive and contained enough to warrant the strike, and I had to be absolutely certain that the coordinates were accurate. I confirmed the location with the platoon, and, with gunfire still sounding in my earpiece, I called the battalion Tactical Operations Center for the strike. Then, I waited.

Two minutes later, the missiles came streaking from the northeast. They arrived with virtually no warning, the sounds of their rockets filling the air only moments before a deafening impact. In the seconds after the strike, the radio was silent, and less than a mile from my location a small cloud of smoke and dust rose from the neighborhood of the engagement. I called to the platoon asking for a report. For a moment, the radio remained quiet, and I worried that the worst had happened. I imagined that the coordinates were wrong, and that my men had taken the hit. I worried that I had failed my men and that I had violated the great trust a commander establishes with his soldiers. I called again for a report, and this time, the platoon called back. The target was destroyed. The building was leveled, and the RPG team was obliterated. My men were safe.

That moment built my confidence. I had been successful as a platoon leader. It was known that I would shortly be awarded the Army Commendation Medal with Valor, and I had developed a reputation as an officer capable of executing demanding missions. My soldiers had begun to call me Capone because of the mafia-like control I had over the area of my command. So, when the Company Commander was called to return to our Forward Operating Base to refuel, re-supply, and debrief battalion, I was put in charge.

For the first time, I now had responsibility over eighty men, four tanks, three Bradleys, and four Strykers. My soldiers were divided into several platoons, and each platoon was supported by different vehicles. Red Platoon had Strykers. Blue Platoon had Bradleys. My platoon, White Platoon, was a tank platoon. One of my tanks led the way for each group, and a single soldier served as point man, moving a few paces in front of and to the left of the tank. His job was to identify potential IEDs. He scanned the ground for copper wires, a sure sign of an explosive device buried in the ground, and when he found them, he would call in to me to request Explosive Ordinance Disposal. After the IED was destroyed, the soldiers behind the tank would enter each building along the street and clear it of any threats. I was directing a large-scale, coordinated mission in a notoriously dangerous area of Iraq, and my command was an integral part of a broader attack involving our entire brigade. I knew it was an opportunity to demonstrate to all the men my ability to lead, and it was my best opportunity to show them that I could be trusted to do what was best for them.

The first moments of my command were overwhelming. My company, Delta Company, dubbed the Death Dealers, was working in conjunction with other companies to clear this section of Baqubah. To my north was Bravo Company, and to the south was Charlie Company. As Delta commander, I choreographed an elaborate dance, ensuring that each of my platoons moved at roughly the same pace in order to prevent one from accidentally moving ahead and coming into the line of fire of another. At first, I had to rein them in. The natural instinct is for each platoon to move at its own pace down the street, but that endangers the mission and other men. From my tank, I directed each group to ensure that they worked together. I had to fashion a team from platoons of men who wanted nothing more than to finish the mission as quickly as possible without regard for the other platoons. Each group moved down a street, calling their coordinates back to me, requesting the destruction of the numerous IEDs and demanding support when the enemy engaged them. My headphones buzzed with their voices, and I tried to negotiate the new terrain as acting Company Commander. I tried to make sense of their voices, and I tried to execute a mission that was already encountering significant resistance.

If all my teams moved together, we could ensure that an area remained clear and that platoons could quickly support each other in the event of a particularly difficult engagement with the enemy. So, I coordinated my platoons and reported the progress of my company as a whole to the companies to the north and south and to my battalion leadership. The plan was for a systematic clearing of Baqubah, and after about an hour of my command, as I began to understand and resign myself to the rhythms of a mission, our company gained confidence in the process. More importantly, my soldiers gained confidence in my ability to lead.

The success of the missile strike on the RPG team offered a clear sign to the men on the ground that I could be trusted to protect them. My men believed that I would provide the support they needed, and they now moved as a disciplined team down the streets. They began to trust my guidance, and they responded by tracking in textbook fashion westward across the city. Our company was working well, and I knew I had a type of control and confidence that comes only from succeeding in a difficult mission. I had a sense that I was living a vocation that was meant for me. I felt like I was embodying the ideal of the American Soldier. I believed that I was doing the right thing.

Three and a half hours into my command, a new IED call came over the radio. My White Platoon sergeant had found another wire. This one, though, was different. I had to ask him several times to describe what he saw. A mound of newly disturbed earth was in the middle of the road. A copper wire, not even vaguely hidden, ran from the mound to a building to the northeast, and then up the side of the building to the second story and into a window. That window had a clear view of the area of disturbed earth.

What my sergeant described was not at all normal, and, given the number of more cleverly disguised IEDs along the route, I was having difficulty making sense of what he was describing to me. The mound and the wire running from it were both in some ways typical. That the wire led up to a window was not entirely typical, but it made some sense given the view it had of the mound. I asked again for him to explain it to me, and I tried to picture what he was describing. It just seemed so obvious. It was as though whoever had devised the IED had made no attempt to hide it. The mound of dirt was obvious, the wire was not hidden from view, and the whole contraption seemed too easy to identify.

I called the situation to the battalion Tactical Operations Center (TOC). The entire mission came to a halt as I discussed the situation with my battalion leadership. It only took a few minutes before another report came back. Locals indicated that the house was an IED factory. The battalion command reported that they believed it to be a terrorist cell. The adjacent companies were pulling ahead. Any more delay and we would corrupt the mission for the entire battalion. The time to decide was running out.

I knew now what I had to do. I had to destroy the house. I could not risk sending men into a house that was an IED factory. I simply had to eliminate the threat altogether. Still, that wire running into the house bothered me. It was all so obvious. Why was it not hidden any better? What was the catch?

I began to sweat. This decision seemed heavier. The earlier missile strike was a no-brainer. My men were under direct fire, and the location of the enemy was clear and the danger was certain. This house, though, was a mystery. I was having a hard time picturing exactly what my sergeant was describing to me, but I knew one thing. I wasn’t going to let fear of making a bad decision control me. I had to protect my men. I couldn’t understand why the IED would be so obvious, but I knew I wouldn’t risk a life trying to find out.

I worked through it all in my head one last time. The house had a wire running from it to a mound in the road. The area was saturated with IEDs, and my men had already been attacked by an RPG team. Locals and my battalion command suspected the house was either an al-Qaida stronghold or an IED factory. My men were concerned about it, and, thus far, they had conducted the mission with a systematic certainty and professionalism. Perhaps most importantly, I felt my men’s lives were at risk. I couldn’t send them into that house. I couldn’t risk that.

I made a final call into the battalion TOC. The response was simple and clear: “We support your decision.” I called for the missiles, and we all waited.

Somewhere to the north, about twenty miles from our location, two GPS-guided rounds turned toward our location and fired from a 155-mm cannon on an artillery vehicle. They lifted from the vehicle and rushed over the city. Behind them, small contrails etched their paths in the sky.

For two minutes, I waited in silence with the men in my tank. The platoon had pulled back and cleared the area around the target. My men had gathered inside their armored vehicles and locked all hatches to protect themselves from the blast. One of my tanks positioned itself on a rise so it could watch the strike. They waited and watched, and my radio was silent as the entire company anticipated the strike. No chatter. No sound. Just the certainty of imminent impact and utter destruction. I looked at my friend Garnica, the gunner in my tank, and I wiped my brow. The heat in the tank was oppressive. I dropped my head, and I wondered if I had made the right decision. I wondered if I had, in fact, done the right thing.

The ferocity of missile impacts turned my attention back to the radio. The explosions rattled our vehicles, and I waited to hear confirmation that the correct target had been hit. Dust and debris rose above the city and mingled with the haze of the afternoon sky, and my radio fell silent.

The silence lingered for a few seconds before my platoon sergeant radioed in. A successful strike. Target destroyed. For a moment, I felt relieved that the missiles flew true. All the doubts I had vanished, and I felt renewed confidence in my decision. Then, within a minute, another voice, broken, sounded over the radio.

“Did – you see – that?”

I leaned in, trying to hear the broadcast more clearly. It wasn’t coming from my company. It was coming from a tank in Bravo Company, just to the north of my men. Even though they had nothing to do with the event, they had a clear view down the street, and they saw the missiles strike.

“Did you see that kid?”

I grabbed my headset, pressing it hard against my ears, trying to hear what they were saying.

I heard them say it again, “Did you see that kid?” and this time, with awful certainty, came a response.

“There were a lot more in there.”

The words hung in the air, and I looked at the men in my tank. A new silence settled in. A deeper, more devastating silence. One that joins men together. One that conspires. One shared by all of us soldiers, from any war, who have witnessed the unspeakable and who, in our attempts to cope, pledge to each other, with simply a glance, not to say a word, not to resurrect what we have destroyed.

This is my voice rising out of that terrible silence.

This is my story trying to order the ruins of that day.

1

They call us “butter bars,” newly minted second lieutenants in the Army. The name refers to the two gold bars on our uniform that indicate our rank, and it reflects a general skepticism about our ability to lead. It suggests that we’re soft. It suggests that we’re inexperienced. It suggests that we’ll make bad decisions.

Even so, we’ve all been through officer training, so, when we are called to leave the States and lead our first missions, we are, if nothing else, eager to put into practice all that we have learned. I know I was anyway. I had been looking forward to my chance to prove myself. I had been wanting to demonstrate my ability to take charge and show the men who were now under my command that I was worthy of following. So, when my company left Ft. Hood, Texas, in October 2006, to begin our deployment to Iraq, I was excited to see action.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!