83,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

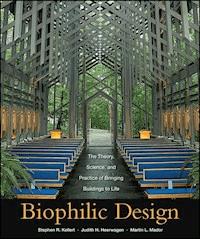

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

"When nature inspires our architecture-not just how it looks but how buildings and communities actually function-we will have made great strides as a society. Biophilic Design provides us with tremendous insight into the 'why,' then builds us a road map for what is sure to be the next great design journey of our times."

-Rick Fedrizzi, President, CEO and Founding Chairman, U.S. Green Building Council

"Having seen firsthand in my company the power of biomimicry to stimulate a wellspring of profitable innovation, I can say unequivocably that biophilic design is the real deal. Kellert, Heerwagen, and Mador have compiled the wisdom of world-renowned experts to produce this exquisite book; it is must reading for scientists, philosophers, engineers, architects and designers, and-most especially-businesspeople. Anyone looking for the key to a new type of prosperity that respects the earth should start here."

-Ray C. Anderson, founder and Chair, Interface, Inc.

The groundbreaking guide to the emerging practice of biophilic design

This book offers a paradigm shift in how we design and build our buildings and our communities, one that recognizes that the positive experience of natural systems and processes in our buildings and constructed landscapes is critical to human health, performance, and well-being. Biophilic design is about humanity's place in nature and the natural world's place in human society, where mutuality, respect, and enriching relationships can and should exist at all levels and should emerge as the norm rather than the exception.

Written for architects, landscape architects, planners,developers, environmental designers, as well as building owners, Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life is a guide to the theory, science, and practice of biophilic design. Twenty-three original and timely essays by world-renowned scientists, designers, and practitioners, including Edward O. Wilson, Howard Frumkin, David Orr, Grant Hildebrand, Stephen Kieran, Tim Beatley, Jonathan Rose, Janine Benyus, Roger Ulrich, Bert Gregory, Robert Berkebile, William Browning, and Vivian Loftness, among others, address:

*

The basic concepts of biophilia, its expression in the built environment, and how biophilic design connects to human biology, evolution, and development.

*

The science and benefits of biophilic design on human health, childhood development, healthcare, and more.

*

The practice of biophilic design-how to implement biophilic design strategies to create buildings that connect people with nature and provide comfortable and productive places for people, in which they can live, work, and study.

Biophilic design at any scale-from buildings to cities-begins with a few simple questions: How does the built environment affect the natural environment? How will nature affect human experience and aspiration? Most of all, how can we achieve sustained and reciprocal benefits between the two?

This prescient, groundbreaking book provides the answers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 958

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Copyright © 2008 by Stephen R. Kellert, Judith H. Heerwagen, and Martin L. Mador. All rights reserved

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 6468600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Biophilic design : the theory, science, and practice of bringing buildings to life / edited by Stephen R. Kellert, Judith H. Heerwagen, Martin L. Mador.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-470-16334-4 (cloth)

I. Architecture—Environmental aspects 2. Architecture—Human factors. I. Kellert, Stephen R.

II. Heerwagen, Judith H., 1944— III. Mador, Martin L., 1949—

NA2542.35.E44 2008

720’.47—dc22

2007023228

Contents

TitlePage

Copyright

Preface

Acknowledgments

Prologue: In Retrospect

Part I: The Theory of Biophilic Design

Chapter 1: Dimensions, Elements, and Attributes of Biophilic Design

Biophilia and Human Well-Being

Restorative Environmental and Biophilic Design

Conclusion

Chapter 2: The Nature of Human Nature

Chapter 3: A Good Place to Settle: Biomimicry, Biophilia, and the Return of Nature's Inspiration to Architecture

A Focus on Function

The Biomimetic Building is a Chimera

Biophilic Design Elements Inspired by Nature

Bringing Nature's Wisdom Back into the Building Process

Can Biomimicry Bring us Back Home?

Chapter 4: Water, Biophilic Design, and the Built Environment

First Questions

Water 101

Biophilia Gets Wet

Chapter 5: Neuroscience, the Natural Environment, and Building Design

Introduction

Biologically Based Design

Biophilic Architecture and Neurological Nourishment

An Architecture that Arises from Human Nature

Three Different Conceptions of Being Human

Level One: The Abstract Human Being

Level Two: The Biological Human Being

Extending Level Two: Expert Knowledge and Patterns

Further Extending Level Two: Human-Machine and Human-Animal Interactions

Level Three: The Transcendent Human Being

Architecture that Transcends Materiality

Conclusion

Fourteen Steps Toward a More Responsive Design

Some Patterns from a Pattern Language

Part II: The Science and Benefits of Biophilic Design

Chapter 6: Biophilic Theory and Research for Healthcare Design

What are Health Outcomes?

Stress: A Major Problem in Healthcare

Biophilia Theory: Why Nature should Foster Restoration from Stress

Research: Nature Views and Restoration

Biophilia Theory: Why Nature Exposure should Reduce Pain

Nature Art in Healthcare Settings

Gardens in Healthcare Facilities

Effects of Daylight Exposure in Healthcare Facilities

Summary and Design Implications

Chapter 7: Nature Contact and Human Health: Building the Evidence Base

The Practice of Clinical Epidemiology

Health Benefits of Nature Contact: The Evidence

Nature and Human Health: Building the Evidence Base

Limits to These Claims

Conclusion

Chapter 8: Where Windows Become Doors

Views

Daylight/Sunlight/Circadian Rhythms/Seasons/Climate

Fresh Air and Natural Ventilation

Natural Conditioning and Passive Survivability

Access to the Outdoors: Extended Space, Nature's Seasons / Textures / Sounds / Smells / Flora / Fauna, and Celebration of Place

Transparency: Access to Life's Activities

Windows Reveal the Spirit of Place

Chapter 9: Restorative Environmental Design: What, When, Where, and for Whom?

The Restoration Perspective

Theory and Empirical Research on Restorative Environments

Restorative Environmental Design: What

Restorative Environmental Design: When and Where

Concluding Comments: Some Prospects and Challenges for Restorative Environmental Design

Chapter 10: Healthy Planet, Healthy Children: Designing Nature into the Daily Spaces of Childhood

Supporting a New Biophilic Culture by Design

Childhood Lifestyle Health Threats

Progressing an Interdisciplinary, Action-Research Strategy

Linking Sustainable Design and Healthy Child Development

Institutionalized Childhood: The Potential of a New Cultural Reality

Early Childhood: Welcome to Planet Earth

Design for Physical Health

Rethinking School Sites

Schoolgrounds as Neighborhood Parks

Neighborhood Parks

Community Nature Destinations

Providing for Children's Needs in Residential Environments: Beyond Playgrounds

Preferred Play Activities: Children's Views

Preferred Play Activities: Adult Recollections

New Biophilic Forms of Residential Neighborhood

1. Clustered Housing and Shared Outdoor Space

2. CUL-DE-SACS and Greenways

3. Alleys

4. Woonerven and Home Zones

Leed Neighborhood Development and Access to Nature

Conclusions

Summary

Chapter 11: Children and the Success of Biophilic Design

Chapter 12: The Extinction of Natural Experience in the Built Environment

PART III: The Practice of Biophilic Design

Chapter 13: Biophilia and Sensory Aesthetics

Let There be Light … and Sound, Odors, Colors, Movement, and Patterns

Resilience

Sense of Freeness

Prospect and Refuge

The Building

The Space

The City

A Walk Through a Biophilic Building

Chapter 14: Evolving an Environmental Aesthetic

Chapter 15: The Picture Window: The Problem of Viewing Nature Through Glass

The Ornamented Picture Window

Conclusion

Addendum: The Problem of Viewing Nature Through “Stone”

Chapter 16: Biophilic Architectural Space

Complex Order

Prospect and Refuge

Enticement

Peril

A Case Study: A Retirement Home

Chapter 17: Toward Biophilic Cities: Strategies for Integrating Nature into Urban Design

Cities of Nature

Green Neighborhoods

Rethinking Urban Infrastructure: Green Streets and Beyond

Thinking Beyond Urban Parks

Organizing Urban Life Around Nature

Reforming Urban Planning Systems

The Vision of Biophilic Cities

Concluding Thoughts

Chapter 18: Green Urbanism: Developing Restorative Urban Biophilia

Chapter 19: The Greening of the Brain

Introduction: Biophilia and an Ecology of the Mind

A Neurological Basis for Design

Designing for the Neocortex

Chapter 20: Bringing Buildings to Life

Chapter 21: Biophilia in Practice: Buildings That Connect People with Nature

A Review of Biophilia

Why Biophilia Matters

Biophilia and Building Design

Balancing Biophilia with Other Green Design Priorities

Justifying Costs

Next Steps for Integrating Biophilic Designs into Buildings

Chapter 22: Transforming Building Practices Through Biophilic Design

Productive Environments

Places that Enhance the Human and Natural Environment

Modern Examples of Biophilia in Design

Roadmap to Transformation

Chapter 23: Reflections on Implementing Biophilic Design

We can Aim Higher

Second Nature: A Return to Buildings that Support Life

Rebalancing the Modern Environment

A New Ethic for Excellence in Design

Conclusion

Contributors

Image Credits

Color Insert

Index

A WILEY BOOK ON Sustainable Design

Preface

Stephen R. Kellert and Judith H. Heerwagen

This book immodestly aspires to help mend the prevailing breach existing in our society between the modern built environment and the human need for contact with the natural world. In this regard, the chapters in this volume focus on the theory, science, and practice of what we call biophilic design, an innovative approach that emphasizes the necessity of maintaining, enhancing, and restoring the beneficial experience of nature in the built environment. Although we present bio-philic design as an innovation today, ironically, it was the way buildings were designed for much of human history. Integration with the natural environment; use of local materials, themes and patterns of nature in building artifacts; connection to culture and heritage; and more were all tools and methods used by builders, artisans, and designers to create structures still among the most functional, beautiful, and enduring in the world.

The authors in this book represent widely diverse disciplines, including architects, natural scientists, social scientists, health professionals, developers, practitioners, and others who offer an original and timely vision of how we can achieve not just a sustainable but also a more satisfying and fulfilling modern society in harmony with nature. Collectively, they articulate a paradigm shift in how we design and build with nature in mind. Still, bio-philic design is not about greening our buildings or simply increasing their aesthetic appeal through inserting trees and shrubs. Much more, it is about humanity’s place in nature, and the natural world’s place in human society, a space where mutuality, respect, and enriching relation can and should exist at all levels and emerge as the norm rather than the exception.

Biophilic design at any scale from buildings to cities begins with a simple question: How does the built environment affect the natural environment, and how will nature affect human experience and aspiration? Most of all, how can we achieve sustained and reciprocal benefits between the two?

The idea of biophilic design arises from the increasing recognition that the human mind and body evolved in a sensorially rich world, one that continues to be critical to people’s health, productivity, emotional, intellectual, and even spiritual well-being. The emergence during the modern age of large-scale agriculture, industry, artificial fabrication, engineering, electronics, and the city represents but a tiny fraction of our species’ evolutionary history. Humanity evolved in adaptive response to natural conditions and stimuli, such as sunlight, weather, water, plants, animals, landscapes, and habitats, which continue to be essential contexts for human maturation, functional development, and ultimately survival.

Unfortunately, modern technical and engineering accomplishments have fostered the belief that humans can transcend their natural and genetic heritage. This presumption has encouraged a view of humanity as having escaped the dictates of natural systems, with human progress and civilization measured by its capacity for fundamentally altering and transforming the natural world. This dangerous illusion has given rise to an architectural practice that encourages overexploitation, environmental degradation, and separation of people from natural systems and processes. The dominant paradigm of design and development of the modern built environment has become one of unsustainable energy and resource consumption, extensive air and water pollution, widespread atmospheric and climate alteration, excessive waste generation, unhealthy indoor environmental conditions, increasing alienation from nature, and growing "placelessness." One of the volume’s authors, David Orr (1999:212-213), described this lamentable condition in this way:

Most [modern] buildings reflect no understanding of ecology or ecological processes. Most tell its users that knowing where they are is unimportant. Most tell its users that energy is cheap and abundant and can be squandered. Most are provisioned with materials and water and dispose of their wastes in ways that tell its occupants that we are not part of the larger web of life. Most resonate with no part of our biology, evolutionary experience, or aesthetic sensibilities.

Recognition of the necessity to change this self-defeating paradigm has led to significant efforts at minimizing and mitigating the adverse environmental and human health impacts of modern development. These efforts have resulted in the growth of the sustainable or green design movement, dramatically illustrated by the extraordinary rise of the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED certification and rating system. While commendable and necessary, these efforts will ultimately be insufficient to achieving the long-term goal of a sustainable, healthy, and well-functioning society.

The basic deficiency of current sustainable design is a narrow focus on avoiding harmful environmental impacts, or what we call low environmental impact design. Low environmental impact design, while fundamental and essential, fails to address the equally critical needs of diminishing human separation from nature, enhancing positive contact with environmental processes, and building within a culturally and ecologically relevant context, all basic to human health, productivity, and well-being. These latter objectives are the essence of biophilic design. True and lasting sustainability must combine both low environmental impact and biophilic design, the result being what is called restorative environmental design (Kellert 2005). This book, in effect, contends that biophilic design has been until now the largely missing link in current sustainable design. The various chapters attempt to redress this imbalance.

The notion of biophilic design derives from the concept of biophilia, the idea that humans possess a biological inclination to affiliate with natural systems and processes instrumental in their health and productivity. Originally proposed by the eminent biologist and one of the volume’s authors, Edward O. Wilson, biophilia has been eloquently described by Wilson in this way (1984:35): "To explore and affiliate with life is a deep and complicated process in mental development. To an

extent still undervalued …, our existence depends on this propensity, our spirit is woven from it, hope rises on its currents." The idea of biophilia is elucidated elsewhere (Wilson 1984, Kellert and Wilson 1993, Kellert 1997), and described in chapters in this volume by Kellert and E. O. Wilson.

Biophilic design is the expression of the inherent human need to affiliate with nature in the design of the built environment. The basic premise of biophilic design is that the positive experience of natural systems and processes in our buildings and constructed landscapes remains critical to human performance and well-being. Various chapters in the volume cite growing scientific evidence to corroborate this assumption in studies of health care, the workplace, childhood development, community functioning, and more. More generally, the authors offer insight and understanding regarding the theory, science, and practice of biophilic design.

Part I of the book focuses on a conceptual understanding of biophilia and biophilic design. Chapters by Kellert, E. O. Wilson, Benyus, Mador, and Salingaros and Masden offer various biological and cultural understandings of the human need to affiliate with natural systems, and how this inclination can be achieved through design of the built environment. The authors address the neglect of the human-nature connection in modern architecture and construction, a condition the eminent architectural historian Vincent Scully described in this way (1991:11): "The relationship of man-made structures to the natural world … has been neglected by architecture… . There are many reasons for this. Foremost among them … is the blindness of the contemporary urban world to everything that is not itself, to nature most of all."

A major cause for this blindness has been the lack of empirical evidence revealing the illogical and self-defeating consequences of designing in adversarial relation to the natural environment. Part II of the book provides much of this needed evidentiary material, particularly the many health and productivity benefits of biophilic design, as well as the harmful consequences of impeding and degrading human contact with natural systems and processes. Chapters by Ulrich, Frumkin, Loftness, and Hartig and colleagues delineate a range of health, physical, emotional, and intellectual advantages of building and landscape designs that facilitate the positive experience of nature. Additional chapters by Moore and Marcus, Louv, and Pyle and Orr describe the importance of nature in childhood maturation, how to foster this connection through the design of residential and educational settings, and the deleterious and potentially disastrous consequences of doing otherwise.

Part III focuses on the practical challenge of implementing biophilic design, most particularly how to transform conventional and prevailing sustainable design practice. Chapters by Heerwagen and Gregory, Kieran, Bloomer, Hildebrand, Fisk, and Bender provide insight and guidance regarding the architectural expression of biophilic design, focusing largely on the building and site scale. Additional chapters by Beatley and Rose emphasize how to foster the human-nature connection at the neighborhood, community, and urban scales, even what Beatley ambitiously calls the creation of "biophilic cities." The challenge of transforming the process of design and development essential to implementing biophilic design is addressed in chapters by Alex Wilson, Cramer and Browning, and Fox and Berkebile.

We believe this volume will greatly advance our notions of sustainable, biophilic, and restorative environmental design. Still, our efforts remain a work in progress, with much more to learn about the elusive expression of the inherent human need to affiliate with nature in the design and construction of our buildings, landscapes, communities, neighborhoods, and cities.

References

Kellert, S. 1997. Kinship to Mastery: Biophilia in Human Evolution and Development. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Kellert, S. 2005. Building for Life: Understanding and Designing the Human-Nature Connection. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Kellert, S., and E.O. Wilson, eds. 1993. The Biophilia Hypothesis. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Orr, D. 1999. "Architecture as Pedagogy." In Reshaping the Built Environment, edited by C. Kibert. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Scully, V. 1991. Architecture: The Natural and the Manmade. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Wilson, E. O. 1984. Biophilia: The Human Bond with Other Species. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Acknowledgments

This timely and, we hope, highly relevant book emerged from a three-day meeting in a beautiful retreat setting known as "Whispering Pines" in rural Rhode Island in May 2006. This extraordinary setting and gathering of leading scientists, designers, practitioners, and others was made possible by the support of many generous benefactors. We particularly appreciate the major assistance of the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation and its visionary president, David Grant. Additional critical support was provided by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Edward and Dorothy Kempf Fund at Yale University, the Vervane Foundation and especially Josephine Merck, the Hixon Center for Urban Ecology at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, and Rev. Albert P. Neilson. Further support for the project was provided by the Henry Luce Foundation.

A number of Yale University students were especially helpful in hosting the symposium and in other vital ways. Particular thanks are due Ben Shepherd. Others who provided critical assistance included Roderick Bates, Christopher Clement, Gwen Emery, Maren Haus, Sasha Novograd, Judy Preston, Chris Rubino, Jill Savery, Ali Senauer, Adrienne Swiatocha, Terry Terhaar, and Christopher Thompson.

Finally, we very much thank our editor at John Wiley, Margaret Cummins, for her considerable confidence and support.

Prologue: In Retrospect

Hillary Brown

During a visit to Turkey more than two decades ago, my companions and I shared pilgrimages to that country’s Arcadian ruins, the rock-cut underworld of Cappadocia, and other rewarding sights. At one stop along the Aegean coast, we spent the night seaside at a resort community. With construction detritus everywhere, it was in a graceless stage of formation, its platted but unbuilt streets undoing the modesty of the village. A dozen hotels along the beach elbowed for sea frontage, gleaming glass and concrete towers, each straining to trump the other as more formally prominent, more luxuriously endowed.

In contrast, the entry to our hotel was undistinguished, even obscure, a suggestive breach in a white wall, solid for its several-storied height. Over the threshold, we found ourselves within a long narrow courtyard open to the elements. The sky overhead (experienced as one would an artwork by James Turrell— not as passive observer, but as participant) was an azure slash. At the far end, the sky ballooned above what appeared to be a plaza.

We were seduced down this street that was mostly self-shaded and cooled by a gentle updraft. Trees and plantings dotted the surfaces, muting the noise of our progress. Underfoot, the upended and sea worn cobble paving was punctuated with sandstone slabs at the entries to adjacent spaces, texturing our sound as alternatively smooth or gritty down the length of the corridor.

Overhead, the walls were faced with windows and doors that opened onto balconies hanging out over this narrow street, beaming like so many smiles. Most casements were flung open, others still shuttered against the morning. Quite a few were peopled, elbows on sills, whispering shared delight at awakening in this communal scene.

The building was vocalizing, its diverse din a contemporary rendering of an ancient Mediterranean village. From the far end came soft social sounds—footfalls, a child’s exclamation, the soft rise and fall of treble and bass voices. Fountains and laughter stippled the air, while clattering silverware broadcast the locale of a cafe. From here, just as our ears took in the softness of breaking waves, our nostrils detected and eyes at once confirmed the full expanse of the Aegean. Magnifying our senses while buffering us from everything else, the hotel was channeling the sea.

I remember my sense of gratification as well as curious agitation in taking in this unexpected place, an experience of architectural pleasure that resonated as both new and unfathomably familiar. For the first (and since then, only) time I knew, as I turned to my companions and announced with conviction, that a woman had designed this building. To my friends’ astonishment, the hotel manager readily confirmed that yes, in fact, a woman-led practice in Istanbul had won the commission.

For years since, I’ve given thought to that sharp, almost physiological insight, that instant knowing-in-my-bones that arose from a shared design sensibility. Was it how she closed our eyes and ears to the chaos of this beach community, or how she choreographed our movements to dilate the experience in time, intensifying this sensual introduction to the sea? Perhaps it was her preference for socialized space, invoking a primordial practice of sharing exquisite places rather than reserving them for private consumption. In setting itself apart, her retreat, after all, recalled the archetypal Islamic car-avansary—that protective, walled compound found at intervals along desert trading routes where travelers together sought refreshment and protection. How compelling was this concept, in contrast to the extravagant resorts next door that claimed visual primacy and exclusivity, ignoring the cultural landscape.

Given an emergent environmental consciousness at the time, I now more fully appreciate this architect’s accomplishment. My ecstatic moment responded to an artistry that was inventive yet contextual—and deeply ecological. Her rendering of bioregion and climate expressed the essence of genius loci—the spirit of the place. Rather than facing the private rooms seaward, she spurned convention by turning them inward, unfolding the sea to us as singular, shared experience.

Just as she intensified the revelation of place, this architect refurbished our faculties by exploiting the intelligence and detailed richness of the natural world, using local resources metamorphosed by time and human agency. She distilled natural materials to their elegant simplicity and rightness of fit. As with ecological designers today, nature was employed here as intrinsic to our biological being, a voice converging through several senses. Our wayfinding to the sparkling sea was intensified with textural, acoustic, and olfactory clues.

Today, many of us realize that successfully communicating the ethical imperative of the green design movement will depend on innovative and compelling expression. In this building, long ago, I glimpsed just such an aesthetic of persuasion—one fundamentally place-based and participatory, experienced through all the senses. While then, this distinguishing green voice struck me as gender-specific, I recognize it today as a responsiveness by no means exclusive to women.

Unnamed at the time, such design sensibilities have recently coalesced for me around the word biophilic and now raise central questions framed by a book on bio-philic design. First and not least is the curious significance of its only recent arrival as a legitimate topic for investigation. Why isn’t biophilic design—perhaps succinctly defined as a creative process driven by, or predisposed toward, bio-logic, which seeks to protect and enhance our link with the forces and faces of nature—an obvious and inherent organizing principle of all works of architecture?

In exploring the dimensions, theories, benefits and practicalities of biophilic design, these essays undertake a range of inquiries. In each new building endeavor, as we renegotiate the boundary between man and the elements, what kind of transactions should take place at the interface? How does the wall become a filter that admits beneficial, yet excludes stressful, sensations? How should we frame a window to function as lens, to better focus on nature while providing a controlled aperture for light, air exchange, and thermal conditioning? If human well-being, productivity and health at home, work, or school may be conferred by an occupant’s access to daylight, views of vegetation and fauna, wind currents, and diurnal and seasonal information, why aren’t these outcomes already a paramount consideration in all building endeavors? Why shouldn’t these natural rights (entitlements, really) feature prominently in our building codes and permitting processes?

An investigation of this intentional, affirmative connection between man and nature makes a provocative contribution to the case for sustainable design. Biophilic design is an emerging voice in building green—a chorus increasingly voluble. It is one that attends to the vital shades and nuances of how we experience environments built for life. For today, in a world of impending climate change and species loss, this design sensibility, one more intuitively biologic in nature, is taking on ever greater social and political urgency.

Part I

The Theory of Biophilic Design

Chapter 1

Dimensions, Elements, and Attributes of Biophilic Design

Stephen R. Kellert

Biophilic design is the deliberate attempt to translate an understanding of the inherent human affinity to affiliate with natural systems and processes—known as biophilia (Wilson 1984, Kellert and Wilson 1993)—into the design of the built environment. This relatively straightforward objective is, however, extraordinarily difficult to achieve, given both the limitations of our understanding of the biology of the human inclination to attach value to nature, and the limitations of our ability to transfer this understanding into specific approaches for designing the built environment. This chapter provides some perspective on the notion of biophilia and its importance to human well-being, as well as some specific guidance regarding dimensions, elements, and attributes of biophilic design that planners and developers can employ to achieve this objective in the modern, especially urban, built environment.

Biophilia and Human Well-Being

As noted, biophilia is the inherent human inclination to affiliate with natural systems and processes, especially life and life-like features of the nonhuman environment. This tendency became biologically encoded because it proved instrumental in enhancing human physical, emotional, and intellectual fitness during the long course of human evolution. People's dependence on contact with nature reflects the reality of having evolved in a largely natural, not artificial or constructed, world. In other words, the evolutionary context for the development of the human mind and body was a mainly sensory world dominated by critical environmental features such as light, sound, odor, wind, weather, water, vegetation, animals, and landscapes.

The emergence during the past roughly 5,000 years of large-scale agriculture, fabrication, technology, industrial production, engineering, and the modern city constitutes a small fraction of human history, a period that has not substituted for the benefits of adaptively responding to a largely natural environment. Most of our emotional, problem-solving, critical-thinking, and constructive abilities continue to reflect skills and aptitudes learned in close association with natural systems and processes that remain critical in human health, maturation, and productivity. The assumption that human progress and civilization is measured by our separation from if not transcendence of nature is an erroneous and dangerous illusion. People's physical and mental well-being remains highly contingent on contact with the natural environment, which is a necessity rather than a luxury for achieving lives of fitness and satisfaction even in our modern urban society.

Biophilia is nonetheless a “weak” biological tendency that is reliant on adequate learning, experience, and sociocultural support for it to become functionally robust. As a weak biological tendency, biophilic values can be highly variable and subject to human choice and free will, but the adaptive value of these choices is ultimately bound by biology. Thus, if our biophilic tendencies are insufficiently stimulated and nurtured, they will remain latent, atrophied, and dysfunctional. Humans possess extraordinary capacities for creativity and construction in responding to weak biological tendencies, and this ability constitutes in a sense the “genius” of humanity. Yet, this innovative capacity is a two-edged sword, carrying with it the potential for distinctive individual and cultural expression, as well as the potential for self-defeating expression through either insufficient or exaggerated expression of inherent tendencies. Thus, our creative constructions of the human built environment can be either a positive facilitator or a harmful impediment to the biophilic need for ongoing contact with natural systems and processes.

Looking at biophilic needs as an adaptive product of human biology relevant today rather than as a vestige of a now-irrelevant past, we can argue that the satisfaction of our biophilic urges is related to human health, productivity, and well-being. What is the evidence to support this contention? The data is sparse and diverse, but a growing body of knowledge supports the role of contact with nature in human health and productivity This topic is extensively discussed elsewhere, such as in chapters in this book by Ulrich, Hartig, Frumkin, and others. Still, the following findings are worth noting (summarized in Kellert 2005):

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!