23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Foundations of the Philosophy of the Arts

- Sprache: Englisch

Black is Beautiful identifies and explores the most significant philosophical issues that emerge from the aesthetic dimensions of black life, providing a long-overdue synthesis and the first extended philosophical treatment of this crucial subject.

- The first extended philosophical treatment of an important subject that has been almost entirely neglected by philosophical aesthetics and philosophy of art

- Takes an important step in assembling black aesthetics as an object of philosophical study

- Unites two areas of scholarship for the first time – philosophical aesthetics and black cultural theory, dissolving the dilemma of either studying philosophy, or studying black expressive culture

- Brings a wide range of fields into conversation with one another– from visual culture studies and art history to analytic philosophy to musicology – producing mutually illuminating approaches that challenge some of the basic suppositions of each

- Well-balanced, up-to-date, and beautifully written as well as inventive and insightful

- Winner of The American Society of Aesthetics Outstanding Monograph Prize 2017

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 430

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Preface and Acknowledgments

Between Baraka and Brandom

Chapter 1: Assembly, Not Birth

1 Introduction

2 Inquiry and Assembly

3 On Blackness

4 On the Black Aesthetic Tradition

5 Black Aesthetics as/and Philosophy

6 Conclusion

Chapter 2: No Negroes in Connecticut

1 Introduction

2 Setting the Stage: Blacking Up Zoe

3 Theorizing the (In)visible

4 Theorizing Visuality

5 Two Varieties of Black Invisibility: Presence and Personhood

6 From Persons to Characters: A Detour

7 Two More Varieties of Black Invisibility: Perspectives and Plurality

8 Unseeing Nina Simone

9 Conclusion: Phronesis and Power

Chapter 3: Beauty to Set the World Right

1 Introduction

2 Blackness and the Political

3 Politics and Aesthetics

4 The Politics–Aesthetics Nexus in Black; or, “The Black Nation: A Garvey Production”

5 Autonomy and Separatism

6 Propaganda, Truth, and Art

7 What is Life but Life? Reading Du Bois

8 Apostles of Truth and Right

9 On “Propaganda”

10 Conclusion

Chapter 4: Dark Lovely Yet And; Or, How To Love Black Bodies While Hating Black People

1 Introduction

2 Circumscribing the Topic: Definitions and Distinctions

3 Circumscribing the Topic, cont’d: Context and Scope

4 The Cases

5 Reading the Cases

6 Conclusion

Chapter 5: Roots and Routes

1 Introduction

2 An Easy Case: The Germans in Yorubaland

3 A Harder Case: Kente Capers

4 Varieties of Authenticity

5 From Exegesis to Ethics

6 The Kente Case, Revisited

Chapter 6: Make It Funky; Or, Music’s Cognitive Travels and the Despotism of Rhythm

1 Introduction

2 Beyond the How-Possible: Kivy’s Questions

3 Stimulus, Culture, Race

4 Preliminaries: Rhythm, Brains, and Race Music

5 The Flaw in the Funk

6 (Soul) Power to the People

7 Funky White Boys and Honorary Soul Sisters

8 Conclusion

Chapter 7: Conclusion

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 02

Figure 2.1 Composite image comparing Nina Simone and Zoe Saldana.

Figure 2.2 Banania advertisement.

Figure 2.3 Nina Simone,

Broadway Blues Ballads

, album cover.

Figure 2.4 Photo of Nina Simone.

Chapter 04

Figure 4.1 Dark & Lovely Announces Bria Murphy As New Global Brand Ambassador.

Figure 4.2 Cover of

Vogue

(April 2008), by Annie Leibovitz, compared with H. R. Hopps’s World War I US Army recruitment poster by media critic Harry Allen.

Figure 4.3 Glenn Ligon,

Self-Portrait Exaggerating My Black Features and Self-Portrait Exaggerating My White Features

, 1998.

Chapter 06

Figure 6.1 Me’Shell NdegéOcello, “Leviticus: Faggot”

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

ii

iii

iv

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

Foundations of the Philosophy of the Arts

Series Editor: Philip Alperson, Temple University

The Foundations of the Philosophy of the Arts series is designed to provide a comprehensive but flexible series of concise texts addressing fundamental general questions about art as well as questions about the several arts (literature, film, music, painting, etc.) and the various kinds and dimensions of artistic practice.

A consistent approach across the series provides a crisp, contemporary introduction to the main topics in each area of the arts, written in a clear and accessible style that provides a responsible, comprehensive, and informative account of the relevant issues, reflecting classic and recent work in the field. Books in the series are written by a truly distinguished roster of philosophers with international renown.

1. The Philosophy of Art Stephen Davies

2. The Philosophy of Motion Pictures Noël Carroll

3. The Philosophy of Literature Peter Lamarque

4. Philosophy of the Performing Arts David Davies

5. The Philosophy of Art, Second Edition Stephen Davies

6. Black is Beautiful: A Philosophy of Black Aesthetics Paul C. Taylor

Black is Beautiful

A Philosophy of Black Aesthetics

Paul C. Taylor

This edition first published 2016© 2016 Paul C. Taylor

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148–5020, USA9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKThe Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Paul C. Taylor to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Taylor, Paul C. (Paul Christopher), 1967– author.Title: Black is beautiful : a philosophy of black aesthetics / Paul C. Taylor.Description: Hoboken : Wiley, 2016. | Series: Foundations of the philosophy of the arts | Includes index.Identifiers: LCCN 2016002850 (print) | LCCN 2016005797 (ebook) | ISBN 9781405150620 (cloth) | ISBN 9781405150637 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781118328675 (pdf) | ISBN 9781118328699 (epub)Subjects: LCSH: Aesthetics, Black. | African American aesthetics.Classification: LCC BH301.B53 T39 2016 (print) | LCC BH301.B53 (ebook) | DDC 111/.8508996073–dc23LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016002850

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

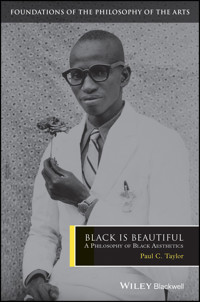

Cover image: Seydou Keita, Untitled, 1952/1955. Gelatin silver print, printed later.Courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, © Keïta/SKPEAC

Preface and Acknowledgments

Between Baraka and Brandom

“I don’t know where to begin (or, it turns out, to end) because nothing has been written here. Once the first book comes, then we’ll know where to begin.”

Barbara Smith, “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism”1

I went into philosophy because I thought it would help me help others think more productively about black expressive culture. This seemed like an important thing to do during the early days of the US post-civil rights era, in those days after world events had undermined the idea that, as Du Bois might say, the walls of race were clear and straight, but before it had seriously occurred to anyone to toy with thoughts of post-racialism. At that moment, black expressive culture – the aesthetic objects, performances, and traditions that defined blackness for many people as surely and as imperfectly as skin color or hair texture do – still seemed important in the ways that the US Black Arts Movement had insisted it was. But the old reasons for assigning it this importance had lost some of their purchase, and the old contexts for creating, experiencing, and understanding black expression were undergoing rapid and radical transformation.

The old reasons for focusing on black literature, film, music, and the rest were artifacts of earlier regimes of racial formation. Prior to the (qualified) successes of the twentieth-century black freedom struggles, black expressive culture mattered to blacks because culture work allowed them to escape, to some degree, more than aspirants to success in business or politics could, the yoke of white supremacist exclusion, and to achieve at a level commensurate with their talents. So blacks could look to entertainers and artists as emblems or defenders of their human possibilities. Black culture workers could show self-doubting blacks as well as negrophobes of other races the true potential of unfettered black strivings, and they could defend the race against the racist images and narratives that dominated western culture. At the same time, black expressive culture also mattered to people of other races, even anti-black racists of other races, and also for a handful of reasons. For some, primitive blacks had their fingers on the pulse of some quintessentially human impulses that over-civilized people of other races had forgotten. For others, blackness could be a symbolic field for working out their own identities and impulses, consciously or unconsciously. For still others, and most simply, blackness was associated with dimensions of human experience that are always of wide interest – it was exotic, titillating, dangerous, and sensual.

This dialectical struggle of colonial and anticolonial approaches to blackness began to lose its relevance after African countries became self-governing, and after black subject populations in settler colonial states began to assert and win something like their full citizenship rights. Put simply: Once Oprah becomes a global media icon, and Toni Morrison wins the Nobel Prize for literature, and Mandela becomes the president of South Africa, and Obama becomes the president of the United States – perhaps better: now that Tim Story can direct summer blockbuster films like The Fantastic Four (for good or ill), and Halle Berry can win an Oscar (more on this later) and headline her own tentpole superhero film (Catwoman), and Okwui Enwezor can curate Documenta and the Venice Biennale, and Michael Jordan and Jay-Z can, like Oprah, become global icons for their skills as performers and as businesspeople – once all of this happens, the old approaches to black expressive culture seem much less pertinent. Why ask culture workers to uplift and defend the race, in the minds of black folks or others, when the work of vindication, in aesthetics and in ethics, has already been done?

Many of the particular developments that I cite above were still some distance in the future when I decided philosophy was relevant to black aesthetics. But the general drift was clearly discernible, as was a widespread incapacity to think intelligently about the cultural dynamics that our new racial orders had unleashed. We were starting to see the import of questions like these: How should African Americans orient themselves to icons of African identity, like kente cloth, especially since those icons had specific meanings to participants in specific African communities, and these meanings were often invisible to people looking through the lenses of US racial politics? Does it make sense to demand that black artists produce “positive” images of black life, now that there is less need to defend ourselves against assaults like Birth of a Nation? Does the widespread adoration of figures like Michael Jordan and Michael Jackson, or, now, of Will Smith and Beyoncé Knowles, mean that racism is over? What does it mean that the most lavishly compensated participants in black practices are often white people? How can we even make sense of the idea of “black practices” after the collapse of classical racialism? Worse, how can we make sense of this idea after explicit racial domination gives way, thereby removing the impetus to close ranks and ignore both the differences between the many distinctive ways of being black and the centrality of interracial exchanges to even the most iconic “black” achievements? And what do we make of the strange ambivalence with which black bodies are still widely regarded, which leaves them both invisible and hyper-visible, desired and despised?

Those questions are only more pressing now, in the world after Quentin Tarantino, Joss Stone, and Justin Beiber, a world populated by symposia on Black Europe and Body Politics2 and by Japanese reggae artists who trek to Brooklyn and Kingston in search of authenticity.3 They are pressing in part because they represent a kind of changing same, though not the one Baraka invites us to contemplate. None of the phenomena I’ve gestured at are new, exactly, which means that we have to account for their persistence. But they are still interestingly distinct from the precedents that we might cite for them, which means that we have to explain the difference between, say, Tarantino and Norman Mailer, Beiber and Elvis Presley, Sidney Poitier and Denzel Washington.

Anyway, as I keep saying, I dimly perceived that these were things worth thinking harder about, in ways that seemed, in my experience, either of little interest to or beyond the capacities of most people. I knew that there was a long tradition of serious reflection on black aesthetics, though that description of the enterprise had become available only recently. And I knew that the tradition had even more recently made its way into the academy, into English departments and programs in cultural studies and other places, carried there by people benefiting from the same political victories that now made it necessary to interrogate the shifts in black culture. My hope was to extend the tradition and join the ongoing conversations, and to do so by bringing the tools of professional academic philosophy to bear on our shared problems.

What I did not adequately understand was the degree to which professional philosophy – the part of the profession into which I had been socialized, anyway – had purposely walled itself off from the places and people with whom I wanted to be in conversation. This turned my desire to join the conversation into an attempt to bridge discursive communities – more precisely, to build a bridge from a particular network of discursive communities, the ones that raised me, to the mainland of inquiry into black aesthetics. And that subtle but profound shift in the project has led to the book that you now hold.

I want to be clear about this background because it bears directly on the structure of the project as it stands. I have recently found myself calling this an exercise in “retroactive self-provisioning,” which means that I have tried to write the book that I’d wanted to read, back when the size of the gap between the work I was prepared to do and the work I wanted to do began to become apparent. So the shape of the project, its proximity to contemporary Anglophone philosophy and its distance from – though not refusal of – the veins traditionally mined by other approaches to black expressive culture, is a function of autobiographical contingencies and vocational choices. I undertook this project in part to fill a void in the expressive and theoretical resources of the intellectual traditions that inform my work, and to dissolve the dilemma that I once thought I faced: study philosophy, or study black expressive culture?

The void that I mention is doubly overdetermined. On the one hand, I was trained by analytic philosophers, and found while in their tutelage that I was interested in classical US thinkers like Emerson, William James, and John Dewey, and in the uses that people like Rorty and Putnam found for their ideas. I found further that following out the latter tradition in the right directions could lead me into productive encounters at the more accessible edges of “foreign” traditions, as represented by the likes of Foucault, Butler, Bordo, and Cavell. This sort of training, which was more ecumenical than it might have been, tends not to inspire curiosity about the likes of Amiri Baraka. On the other hand, I had long nurtured an interest in black critical thought. This began during my time at an HBCU (historically black college and university) in the 1980s, and has deepened in recent years as I’ve worked in greater proximity to scholars in African American Studies. This sort of training, for its part, tends not to inspire curiosity about the likes of Robert Brandom.

There is a small area of overlap between the traditions that claim Brandom and Baraka, an area occupied in increasing numbers by students and scholars of Africana philosophy and newer modes of political theory. But the bit of that work that attempts a rapprochement from the side of the philosopher tends not to fill the void I have in mind, for three broad reasons. First, much of it reproduces mainstream philosophy’s indifference to aesthetics, and focuses, albeit quite reasonably, on questions from other precincts of philosophy. Think here, for example, of the composition of the important companion volumes to African American and African philosophy, as those documents stand as of this writing. They are massive texts, and vanishingly little of their huge page counts are occupied with work in aesthetics.

Second, the work that does take up aesthetic questions tends to set aside the aspiration to explore black aesthetics as a whole – call this the conjunctural aspiration, for reasons I’ll come to in Chapter 1 – and focuses instead on particular idioms, periods, or thinkers. Think here of the fine work that people like Tommy Lott and Nkiru Nzegwu have done on particular expressive idioms and media, or of the brilliant new work in political theory that treats Baldwin and Du Bois as thinkers whose approaches to the aesthetic and the political are inseparable. This is important work, but there is a need for more studies of the sort undertaken by people like Cornel West, Sylvia Wynter, and Fred Moten, work that aspires to think philosophically about the black aesthetic as such.

And third, the work that accepts the conjunctural aspiration tends to remain at a somewhat greater distance than I would like from the philosophical resources that I value. I am thinking here of philosophers who have left the profession to become, as Cornel West puts it, men and women of letters, not beholden to any narrowly specialized and professionalized approach to the life of the mind. These are people like West himself, of course, but also like Angela Davis and Adrian Piper, all of whom are card-carrying philosophers but whose interests – interests in, among other things, the issues that I will soon assign to the study of black aesthetics – have led them away from professional academic philosophy and into spaces that are in some ways (ways I don’t have time to explore) more open.

I am also thinking, though, of figures who have not put aside academic philosophy but who have instead worked in or near it using vocabularies that are to some degree incompatible with my own. I think here of Moten and Wynter, and of others who have drunk deeply from the wells of poststructuralist thought. But I think also of Alain Locke, who did his work before the mid-twentieth-century ferments – in philosophy and in black cultural criticism – that shaped my vision of our shared interests. For this reason, Locke’s arguments are for me nearly as distant and in need of translation as Royce’s, or Hegel’s, or Moten’s. I accept that this need for translation is a shortcoming of my training, or of what I’ve made of myself in the wake of that training. It is surely the case that Locke’s work (like Royce’s, and Hegel’s, and Moten’s) should be less alien to me than it is. Still, one must on occasion cast down the buckets where one stands, which is to say that this project is an experiment in mining the resources that my upbringing, whatever its limitations, has prepared me to use.

All of that to say: My hope in this book is to use resources in and near the dominant traditions in Anglophone philosophy – which is what I will usually mean when I refer to “philosophy” here – to reconcile the black aesthetic with the contemporary race-theoretic consensus. If I do this properly, I will have written the book that I wanted, and could not find in graduate school, when I began to read Du Bois and Morrison through Danto and Dewey. And I will have given people who share my intellectual upbringing an accessible way into the study of black aesthetics.

Thinking, done properly, is about incurring debts. We end up beholden to our interlocutors and teachers, living and dead, to our correspondents and collaborators, and to the people who have sustained us on our journeys through, and to and from, the worlds of our ideas. It is not clear whether I’ve thought properly here, but I have incurred the debts.

First, there are a number of audiences and commentators to thank, many of whom heroically masked their puzzlement as I tried to locate the questions and claims that make up this book. I am particularly indebted to the philosophy faculty and students at Rhodes University in South Africa, who have heard me work through the ideas here over several years of visits to Grahamstown. Ward Jones, Pedro Tabensky, and Samantha Vice have been gracious hosts, good friends, and generous conversation partners, and I am glad to have them as colleagues and comrades. Lectures at the University of Michigan, the University of San Francisco, the University of Cape Town, the University of the Eastern Cape, Middle Tennessee State University, Otterbein University, and Skidmore University have been similarly fruitful, thanks in large part to the comments and thoughtfulness of Robin Zheng, Ron Sundstrom, Elisa Galgut, Antjie Krog, Mary Magada-Ward, Stephanie Patridge, and Catherine McKeen. The philosophers at Bucknell University, led by Sheila Lintott, were especially kind as I worked toward the slowly dawning questions that now inform the chapter on funk. It has been particularly enlightening to share these ideas with faculty and students at historically black colleges and universities, both here and abroad. For these opportunities I have to thank Anika Simpson and Marcos Bisticas-Cocoves at Morgan State, Barry Hallen at Morehouse, and Abraham Olivier at the University of Fort Hare.

Audiences and commentators at various professional gatherings have also been quite helpful, beginning with the International Society for African Philosophy and Studies, where this project got its first public airing. Since then the good people of the Alain Locke Society, under the leadership of Leonard Harris and Jacoby Carter, and of the American Philosophies Forum, led by John Stuhr, invited me to give presentations that proved especially fruitful for this work. Similarly, opportunities to speak at meetings of the American Philosophical Association and the American Society for Aesthetics led to useful comments from Devonya Havis and Luvell Anderson, and from generous and attentive audiences.

I have also benefited from the edifying conversations put on by various college and university institutes and centers. I particularly appreciate the generosity of the University of Connecticut’s Institute for African American Studies, led at the time by Jeff Ogbar and then by Olu Oguibe; of Florida Atlantic University’s Center for Body, Mind, and Culture, under the direction of Richard Shusterman; of the University of Kentucky’s African American & Africana Studies Program, led by Frank X. Walker; and of the Frederick Douglass Institute at East Stroudsburg State University, represented in its dealings with me by Storm Heter.

This work would of course not have been possible without the financial support of various institutions, and without the sustained encouragement and criticism of a number of individuals. I received generous research support from my employers at Temple and Penn State – much more generous support than I could reasonably have expected. And I enjoyed rich and vibrant intellectual communities in both places. At Temple, my colleagues Lewis Gordon, Miriam Solomon, Espen Hammer, and Kristin Gjesdal, along with students Danielle LaSusa, Joan Grassbaugh-Forry, Robert Main, and Avram Gurland-Blaker, helped me frame the project that became this book. Lewis was particularly helpful, not least in providing a model for moving between, and sometimes refusing, disciplinary boundaries. At Penn State, my colleagues Kathryn Gines, Vincent Colapietro, Shannon Sullivan, and Robert Bernasconi have been an invaluable support system, with Vincent in particular helping me to keep alive the hope that philosophy can be made safe for Ralph Ellison and Regina Carter. The Penn State students have been an inspiration, with their determination to avoid the kind of either-or choices that lead me in middle age to write the book that I needed in grad school. I am particularly grateful in this regard for the conversations I’ve had, in seminar rooms, sports bars, and chain breakfast restaurants, with Lindsey Stewart, Alphonso Grant, and Jamelia Shorter.

A number of individuals outside my workplaces have made the deepest impact on this work. Jeff Dean green-lit the project during his time at Wiley and then waited, with patience beyond measure, for it to come to fruition. I am grateful to Jeff and to Nicole Benevenia and Tiffany Mok for their serenity in the face of interminable delays. Cornel West and Susan Bordo, by argument, instruction, and example, helped me think it might be possible to build the intellectual bridges that I wanted to build, to take black expression seriously as an occasion for and record of deep thought and profound achievement, and to put philosophy productively into conversation with cultural criticism. Eddie Glaude was and long has been an invaluable conversation partner, inspiration, brother, and friend, and has shown me, in a number of ways over a number of years, how one might bring the exact intellectual and cultural resources that interest me into a fruitful and fascinating combination. Charles McKinney, Mark Jefferson, and Charles Peterson reminded me that the life of the mind includes – no, requires – laughter, and that the bonds of brotherhood remain intact across borders and in virtual conversation. To Eddie, Chuck, Mark, and Pete, I say: Ankh, Tchau, Seneb.

Anne Eaton gave me hope for philosophical aesthetics, and, sometimes, for philosophy, and pushed me to think harder and more carefully about every aspect of this project, and about much else besides. This book would not exist without her, though it would surely be better if I had listened to her more often. Siobhan Carter-David reminded me, in word and deed, of the exciting work that people in other fields are doing in this area, and helped me keep keeping on when my interest and energies were flagging. Eduardo Mendieta, Anika Simpson, Kelly Ellis, and Nikky Finney offered just the right encouraging words, I suspect more encouraging than any of them knows, at just the right moment. And Philip Alperson endorsed the idea of this project early on, and gave me the opportunity to pursue it with Wiley.

My brother Mark inspired me with his commitment to the working artist’s life, and to cultivating the craft that makes the life possible. If I have become one-tenth the writer that he is a musician, and if I’ve studied expressive culture with one-tenth the care that he devotes to producing it, then I will have achieved something.

My teachers Peter Kivy and Howard McGary have left indelible marks on this project, though in different ways. Peter showed me that one can attend to the quality of one’s writing and of one’s thinking at the same time, and modeled a way of putting both arts in service of productive reflection on the philosophy of music. I found myself rehearsing his arguments much more frequently in these pages than I had anticipated. I hope this pleases him as much as it pleases me. Howard’s mark on the book is less direct, but no less substantial. I hope to have learned from him how to engage carefully and charitably with all comers, how to work patiently through an idea until it yields whatever it has to offer, and how to do all of this in conversation with the best of the black intellectual tradition, taking Audre Lorde as seriously as John Locke.

Finally, my wife, Wilna Julmiste Taylor, showed me every day what it is to walk and live and love in beauty. She has supported me through this project, and through all the detours that the book and our lives have taken, to a degree that I do not deserve. Her reminders about the business of culture work pull me back from the land of austere academic reflection, and enrich my reflections with real-world detail. And her joyfulness, spirituality, and passion remind me that experience both has and should aspire to have, as Dewey rightly but inelegantly put it, aesthetic quality. Like the dewdrops love the morning leaves, honey.

Notes

1

Barbara Smith, “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism,”

The Radical Teacher

7 (March 1978), 20–27; reprinted in Winston Napier, ed.,

African American Literary Theory

(New York: NYU Press, 2000), 132–146, 132.

2

“Black Europe and Body Politics,”

Africa is a Country

(blog), posted July 8, 2014,

http://africasacountry.com/2014/07/projects-black-europe-and-body-politics/

(accessed November 30, 2015). “For those not familiar with this groundbreaking project, BE.BOP is a curatorial project, in co-production with

Ballhaus Naunynstrasse

, that includes exhibitions, presentations, screenings and roundtables by artists (among others) from the Black European Diaspora. This project seeks to fill a gap when it comes to deconstructing the coloniality of western art and aesthetics in Europe” (par. 1).

3

Josh Chamberlain, “How to Be a Japanese Reggaephile,”

villagevoice.com

, posted July 28, 2009,

http://www.villagevoice.com/2009-07-28/music/how-to-be-a-japanese-reggaephile/

(accessed July 3, 2013).

Chapter 1Assembly, Not Birth

It is 1790, and you are at a seaport in South America. The port is part of the Dutch colony that has since become the country of Suriname, and it is a vital part, if the amount of traffic you see is any indication. One of the many ships here has just docked, and the crew is busy hustling its cargo above deck. The cargo is, in point of fact, hustling itself above deck. The ship, it turns out, is a slave vessel, just arrived from the Dutch Gold Coast, in what is now Ghana.

The forty or so people who make their way up from the cargo hold appear much the way you would have expected, had you expected them. They are dark-skinned and slender, and some give the appearance of being quite ill. They are solemn, apparently resigned to their new fates in their new world. Some have difficulty standing, and most are blinking in the sunlight.

These new African Americans surprise you in only one respect. They have stars in their hair.

Not real stars, of course. The new arrivals have had their heads shaved, leaving patches of hair shaped like stars and half-moons. Just as you begin to wonder how the ship’s crew settled on this way of torturing their captives or entertaining themselves, you receive a second surprise. Not far from where you are standing, a man who seems to be the ship’s captain is speaking with a man who seems to have some financial interest in the ship’s cargo. The capitalist asks the captain why he cut the niggers’ hair like that, and the captain disclaims all responsibility. “They did it themselves,” he says, “the one to the other, by the help of a broken bottle and without soap.”

1 Introduction

The story of slaves with stars in their hair comes from a groundbreaking anthropological study called The Birth of African American Culture.1 The authors of the study, Sidney Mintz and Richard Price, report an eyewitness account of something like the events described above, and use it to support one of their key arguments. They mean to reject and correct certain received ideas about the pace at which Africans became Americans. They hold that distinctly African American cultures emerged quite early on, as enslaved Africans built wholly new practices and life-worlds out of the various old worlds – from different parts of Africa, as well as from Europe and the Americas – that collided in modern slave-holding societies. In the case of the new Americans in this story, the process of cultural blending began before they even reached shore, with an act of “irrepressible cultural vitality” that bridged their different ethnic backgrounds, and that transcended their presumably divergent ideas about adorning the body.

Mintz and Price might have made a slightly different and in some ways broader point, a point not about the birth of African American culture but about the birth of black aesthetics. The uprooted Africans in the story were positioned to become African Americans because they had first been seen and treated as blacks. They put stars in their hair in response to this forced insertion into the crucible of racialization. Having been stripped as much as was possible of their preexisting cultural armament, they had to replace it with something, to put some stylized barrier between themselves and the new social forces with which they would be forced to contend. Instead of entering the new world in the manner of the animals they were thought to be, unadorned, unmarked by the self-conscious creation of meaning, they found common cause in the essentially human act of aesthetic self-fashioning.

This sort of activity, I will want to say, is at the heart of the enterprise that has come to be known by the name “black aesthetics.” Insisting on agency, beauty, and meaning in the face of oppression, despair, and death is obviously central to a tradition, if it is that, that counts people like Toni Morrison, Aaron Douglas, and Zora Neale Hurston among its participants. And reflecting on this activity is central, I will also want to say, to the philosophical study of black aesthetics.

We might start toward the philosophy of black aesthetics by rethinking the metaphor that organizes the Mintz–Price study. They speak of birth, a notion that could lead careless readers to overlook the amount of artifice and improvisation that people put into making a shared life. But think of what you saw at that South American port. A group of uprooted Africans engaged in an act of bricolage: they used what was at hand, both culturally and materially, to cobble together the beginnings of an African American culture. It appears that these cultures are not so much born as assembled.

The philosophical study of black aesthetics also involves a kind of assembly, in a sense that I will soon explain. I stress the philosophic nature of this enterprise because black aesthetics has been developed in many different ways, but none, as far as I know, involve a sustained examination from the standpoint of post-analytic philosophy. This book will, I hope, correct for this oversight.

My aim in this introduction is to answer some preliminary questions concerning the project, and to gesture at what the other chapters will bring. The preliminary questions I have in mind emerge rather directly from the basic framing that I’ve given the project so far. First, to paraphrase cultural theorist and sociologist Stuart Hall: what is the “black” in “black aesthetics”? Second, in the same spirit: what is the “aesthetic” in “black aesthetics”? Third: what good is a philosophy of black aesthetics? And fourth: why discuss any of this in terms of assembly?

2 Inquiry and Assembly

In an essay on the Black Arts Movement in 1980s Britain, Stuart Hall introduces the sense of “assembly” that I’ll use here. He writes:

This paper tries to frame a provisional answer to the question, How might we begin to ‘assemble’ [our subject] as an object of critical knowledge? It does not aspire to a definitive interpretation…. What I try to do … is ‘map’ the black arts … as part of a wider cultural/political moment, tracking some of the impulses that went into their making and suggesting some interconnections between them. I ‘assemble’ these elements, not as a unity, but in all their contradictory dispersion. In adopting this genealogical approach, the artwork itself appears, not in its fullness as an aesthetic object, but as a constitutive element in the fabric of the wider world of ideas, movements, and events.2

On this approach, assembly refuses the quest for a “definitive interpretation” – think here of necessary and sufficient conditions, or of static, trans-historical essences. It aspires instead to identify, gather together, and explore the linked contextual factors in virtue of which we might productively and provisionally comprehend various phenomena under a single heading. And it takes seriously the degree to which these contextual factors involve the historical, cultural, political, and, in the eighteenth-century sense of the term, moral dimensions of human social affairs.

The method of assembly makes it easier to credit the complexity of historically emergent social phenomena – what Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci encourages Hall and others to call “conjunctures.” A conjuncture is “a fusion of contradictory forces that nevertheless cohere enough to constitute a definite configuration.”3 Assembly is the mode of inquiry that allows us to see and account for the coherence of the configuration without glossing over the respects in which it remains, in a sense, incoherent.

Complexity and relative incoherence are important aspects of dealing with the historical dimensions of social phenomena. In dealing with movements or cultural epochs it is often tempting to fetishize temporal landmarks or origin points. But, Hall points out, “[t]he forces operative in a conjuncture have no single origin, time scale, or determination…. [They] are defined by their articulation, not their chronology.”4 That is, conjunctural moments come into view when otherwise independent factors converge in ways that it pays us to think of as constituting something new.5 For example, the period that we know as The Sixties doesn’t begin on January 1, 1960; it begins when the forces that make The Sixties matter come together enough to warrant our attention – which is why it begins at different moments for different people, and why historians sometimes talk about the late fifties part of the Sixties. So one consequence of adopting the method of assembly is that it reminds us to avoid “giving [the conjunctural subjects of our inquiries] a sequential form and imaginary unity they never possessed.” Instead, we should define them the way we define generations: “not by simple chronology but by the fact that their members frame the same sorts of questions and try to work through them within the same … horizon or … problem-space.”6

These lessons of the method of assembly are particularly useful for a study of black aesthetics. Like Hall’s study of the Black Arts Movement in the UK, this book will need to assemble its subject as an object of knowledge, not least because variations in idiom and in regional and national practice have created “a series of overlapping, interlocking, but non-corresponding histories” that defeat any appeal to a single origin or time scale.7 (As a pragmatist, I think we always assemble objects of knowledge; but I mean here to invoke the specifically Gramscian resonances of Hall’s use of the idea, and to credit the distinctive challenges of trying to tell a single story about several centuries of transnational black expressive culture.) The only way to think responsibly and all at once about something called “black aesthetics” is, as Hall puts it, to comprehend under one concept, albeit provisionally, the “condensation of dissimilar currents” that just is the history of black expressive practice.8

This Gramscian approach has its limits, in just the places Hall suggests. There are of course the intrinsic dissatisfactions that come with the inability to index a social fact to definite temporal beginnings and endings. And the expressive objects and practices that give this book its subject matter will not appear here, as Hall says, in their fullness as aesthetic objects, due to the relative weight I’ll have to place on considerations apart from the work of criticism. To the first point: the study of complex, unruly phenomena can also be intrinsically satisfying, not to mention that reality just is unruly, no matter what we’d prefer. And to the second point: a different sort of book would spend more time on criticism – on accounting for and evaluating the experiences that expressive objects underwrite in terms of the relevant features of the objects – and less on theory – on elucidating some of the wider contexts that should inform the critic’s work. But this is not a work of criticism, in part because one basic conceit of the book is that the most productive way to think of black aesthetics is not centrally concerned with finding a unitary system of norms for producing or evaluating artworks.

It should be clear, then, that I think of the limits on a conjunctural approach as parameters, not as failings. Instead of, say, providing a definitive catalogue of the aesthetic norms that have governed every black community since the fifteenth century, I aim to assemble the interest in such norms, and much else, into the subject for academic philosophy that similar inquiries have never managed, or cared, to create. I hope to flesh out the familiar thought that there are philosophic continuities linking Edwidge Danticat to W. E. B. Du Bois, The Last Poets to the Suriname barbers. I want to map the philosophic dimensions of black aesthetic practice, by connecting them explicitly to the wider problematic of racial formation under white supremacy.

The vision of a unified black aesthetic – the vision I am refusing – is not unfamiliar. Practically every account of black expressive practice either endorses or contends with some version of it. Until recently, though, most versions of the idea relied on the problematic assumptions of classical racialism, in both white supremacist and black vindicationist forms. And the work that has gotten past these difficulties has often given up the ambition of thinking black aesthetics all at once, and focuses instead on particular disciplines, time periods, locations, or figures. There is considerable value in this narrower, more specialized work. But there is also some value in taking a more expansive view, provided that we can find a theoretically respectable unifying principle.

To my mind, the best short statement of an acceptably expansive approach comes from art historian Richard Powell. In Black Art: A Cultural History, he explains that the concept of the black aesthetic does not pick out the “singular and unrealistically all-inclusive” cultural monolith that Shelby’s cultural nationalists want to find;9 instead it denotes “a collection of philosophical theories about the arts of the African diaspora.”10 Where Powell says “theories,” I would say “arguments” or “registers of inquiry.” Where he invokes “the African diaspora” I would instead invoke the collection of life-worlds created by and primarily identified with people racialized as black. And while he ultimately focuses on the essentially post-liberation and postcolonial standpoint of the Black Power era, I would cast the net somewhat wider and attempt to locate the poets and dramatists of Black Power on a wider field of thought and action, alongside Barbara Smith, the Suriname barbers, and many others.

These differences aside, though, Powell outlines the basic strategy of this book. I aim to save and develop the intuition that there is a single thing worth calling “black aesthetics.” And I mean to do this by appealing not to the fictive unity of monolithic, supernaturally harmonious, racially distinct culture groups, but to the essentially philosophic preoccupations that routinely animate and surround the culture work of black peoples.

As I’ll use the expression, then, based on the foregoing argument for epistemic assembly, to do “black aesthetics” is to use art, criticism, or analysis to explore the role that expressive objects and practices play in creating and maintaining black life-worlds. The appeal to exploration here is more expansive than it may appear. One can explore something by trying to give an account of it, in the manner of a scientist. But one can also explore something by poking around, in the manner of an explorer. In this sense artists explore the roles that expressive objects can play by trying to make them play one role or another, or by participating in and commenting on previous attempts to do this. (I think here of Glenn Ligon’s appropriation of slave narrative frontispieces.)11 The idea to refer to something as a black aesthetic comes down to us only from the 1960s, when some of the people formerly known as Negroes decided that self-identifying as black would help turn the page on the historic failures and ideological limitations of the past.12 But the work itself began long before the name caught on. The work began whenever and wherever the creation, analysis, and criticism of expressive objects first became crucial to the racial formation processes that produce and sustain the social phenomena that we think of as black people.

3 On Blackness

The idea of assembling black aesthetics presupposes that there is a responsible way of appealing to racial blackness. So the next question to take up is perhaps the most obvious one: what is the black in black aesthetics? It is possible, I suppose, to remain unmoved by this question, or to think that the answer is obvious. There is however no shortage of “obvious” conceptions of blackness, and some of these pretty quickly reveal themselves to be problematic. For these reasons, it is important to be clear about how this book will use “blackness” and “race” and all their cognate terms.13 On the way to settling the meanings of these terms, we will also have to clarify some other issues, including the role that the idea of modernity will play here.

The first thing to say is that the “black” in “black aesthetics” is obviously a racial category, and only slightly less obviously a category that picks out, as W. E. B. Du Bois once said, the people who would have had to ride Jim Crow in 1940s Georgia.14 This may seem to put the matter rather too simply, in light of all the ethical and conceptual difficulties that attend the practices of racial ascription and identification. But there are many different ways to commit oneself to understanding and using racial categories – a commitment that I will indicate with the term “racialism.”15 And some of these ways have been crafted precisely to avoid or respond to these difficulties. The classical race theory made famous by white supremacists, anti-Semites, and neo-Nazis is what worries most of the people who fear and avoid race-talk. But anti-racists, social theorists, and social justice advocates have developed forms of critical race theory that use race-talk to understand and grapple with the social, ethical, and psychocultural conditions that classical racialism helped bring into being.16

The distinction between critical and classical race theory is not fine-grained enough to capture all of the varieties of racialism, each with its distinctive ontological and ethical commitments. Deciding which of these commitments is or ought to be in play has historically been one of the tasks that frames the enterprise of black aesthetics. The key for current purposes is just that some version of racialism is in play for students and practitioners of black aesthetics, and that this racialism can be critical rather than a form of racism or invidious essentialism.

This open-ended appeal to critical racialism is consistent with a broad consensus that has recently emerged in philosophical race theory.17 Most race theorists now understand race critically, as a human artifact that is interestingly linked to European modernity, importantly political in its conditions and consequences, unavoidably social in its reach and structure, and essentially synecdotal in its operations. Each element of this consensus requires some elaboration.

To approach race critically is to refuse classical racialism. This means to refuse a picture of hierarchically ranked, naturally distinct human populations, reliably defined by clusters of physical and non-physical traits. For the critical racialist, race, whatever it is, is not what Samuel George Morton and Thomas Jefferson – and, for that matter, Marcus Garvey – thought it was.

To approach race as an artifact is to accept that our race-talk refers to the products of human agency. To say this is not yet to say that there can be no biological or evolutionary component to raciogenesis. It is simply to cast one’s lot with the sort of view one finds in standard formulations of racial formation theory: that racial phenomena are products and records of human activities rather than prefabricated features of the universe.

To insist on the political significance of race is to insist not just on the standard racial controversies. It is also, and more importantly, to highlight the robust relationship between race-thinking and the modern world’s basic political structures, from the growth of capitalism to the development of liberal ideas of freedom and democracy. Race has been central to the conceptions of citizenship, justice, individuality, and more that define the modern project, and it remains central to contemporary elaborations and emanations of this project.