18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

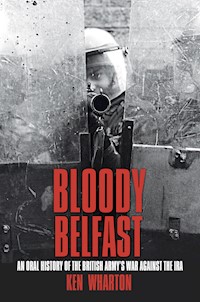

Former soldier Ken Wharton witnessed the troubles in Northern Ireland first hand. Bloody Belfast is a fascinating oral history given a chilling insight into the killing grounds of Belfast's streets. Wharton's work is based on first hand accounts from the soldiers. The reader can walk the darkened, dangerous streets of the Lower Falls, the Divis Flats and New Lodge alongside the soldiers who braved the hate-filled mobs on the newer, but no less violent streets of the 'Murph, Turf Lodge and Andersonstown. The author has interviewed UDR soldier Glen Espie who survived being ambushed and shot by the IRA not once, but twice, and Army Dog Handler Dougie Durrant, who, through the incredible ability of his dog, tracked an IRA gunman fresh from the murder of a soldier to where he was sitting in a hot bath in the Turf Lodge, desperately trying to wash away the forensic evidence. Wharton's reputation for honesty established from previous works has encouraged more former soldiers of Britain's forgotten army to come forward to tell their stories of Bloody Belfast. The book continues the story of his previous work, presenting the truth about a conflict which has sometimes been deliberately underplayed by the Establishment.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Sadly in Northern Ireland, the war we were fighting was not recognised, nor the troops, nor the injuries and seldom the deaths; we received our Christmas gifts and letters by default but nevertheless they were appreciated. There was no welcome home, no celebrations; in fact I recall my service medal was thrown at me across a clerk’s desk and I was told to sign for it, but that was the way it was.

Lee Sansum, Royal Military Police

This book is dedicated to the following people:

To the memory of the 21 soldiers who died before Robert Curtis, to whom history and our Government have denied the honour of public recognition

To all those soldiers and former soldiers who helped me and became my friends

To every ‘Brick’ Commander and to every soldier who walked backwards down the streets and roads and country lanes of Ulster

To every CVO; surely the worst job in the world

To Dave Hallam, Tim Marsh, Kevin Stevens, John Moore, Darren Ware, Ken Ambrose, Alan Holborough, Phil Jones and the rest of the Jackets

George Prosser and the ‘Kingos’

Tommy Clarke and Kev Wright and the RCT

John Swaine and Mick Pickford and the Royal Artillery

David Dews and the Fusiliers

Arfon Williams and the RRW

Geoff Smith and the ‘Arfers’ (Light Infantry)

Eddie Atkinson and the Green Howards

To Dave Langston and the ‘Slop Jocks’

To Robert Nairac; denied the honour of a known and lasting grave

To Jasmine Curtis whom I have never met; she must be so proud of her Dad

To my late uncle, Tommy Wharton (1935-97)

To all those who wore the badge of the UDR; to every member of NIVA

To the good people of Ulster who never wanted terrorism

Above all, this is dedicated to the memory of the 1,301 identified – so far – who never returned home to their families.

To my late parents, Mark Clifford Wharton and Irene Wharton. They brought me into this world and made me what I am today.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In the first two volumes of oral histories of the Northern Ireland troubles, I lavished praise on my many friends in the Royal Green Jackets. I can see no good reason not to do exactly the same again as I acknowledge the many contributors from the finest regiment in the long, glorious history of the British Army.

Ken Ambrose, Dave Hallam, Darren Ware, Tim Marsh, Kevin Stevens, Mickey Lee, ‘Vach’, Mick Copp, David Harding, James Kinchin-White and all the others; thank you from the bottom of my heart for your help, support and encouragement. ‘Always green; forever green.’

To Mick Pickford, John Swaine, Mick Potter and all the other ‘Drop Shorts’ who helped me. Eddie Atkinson, Pete Townend, Ray Gasgoigne, Phil Brooks and all my other ‘Green Custard’ mates; lads you did me proud.

Thanks to George Prosser, Paddy Lenaghan, Peter Oakley, Frenchie and the other Kingos. Richard Nettleton and the other ‘woodentops’. Tommy Clarke, Kev Wright, Lawrence Jagger and the other ‘Rogues, Cutthroats and Thieves’.

Phil Winstanley for all you suffered at MPH; Tiny and June Rose; I can only hope that my eternal gratitude will make up in some small way for the lack of gratitude shown to you by our Government. Thanks to Tim Castle, Geoff Smith and all my new-found ‘Arfers’ friends in the Light Infantry.

Mike Day, who refused to accept the enormous credit which he so richly deserves.

Andy Thomas, Steve Norman and the other ‘angle irons’. You never let me down. Haydn Davies, Arfon Williams and Andrew Bull, Royal Regiment of Wales; you all gave so much and I thank you for your endless support. To Bill ‘You can’t shoot at me; I’m REME’ Jones; a tireless contributor. Dougie Durrant and all the boys at the Army Dog Unit; great canine tails (sic).

To Jimmy Mac, Glen Espie, Jim Henderson and all the others who wore the Harp cap badge of the UDR; you did a magnificent job over there and you continue to do the same for me.

The boys at NIVA have never stopped supporting me and I have to mention Big Stevie, Onion, Andy Bennett, Von Slaps and Dave Langston who keeps threatening to post me a 25-year-old ‘egg banjo’ via Australia Post; thanks to you all.

This list could never be complete and if you are omitted, please be aware that I will be eternally grateful for all that you have done, for the Army, your country, your family and lastly, for me.

Many thanks to Paul Crispin for the use of his photographs. They are some of the best of images of the Troubles I have seen. Good luck as a photojournalist.

To Helen, my partner; thank you for all your love and patience, and for putting your arms around me when I have sat and sobbed at my computer as yet another tragic story from Northern Ireland has meant that I have had to type through a veil of tears. Too much dust in the computer room!

Finally, to all of you who believed in me and trusted me to tell our stories with honesty and with sincerity; your enthusiasm knows no bounds. With the level of support that you have given me, it’s no wonder that we all belonged to the best bloody Army in the world.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

The Voices of the British Army in Northern Ireland

The Twenty-One Soldiers who Lost their Lives Before Robert Curtis

Foreword by Andrew MacDonald, Late Kings Own Border

Preface by Mick O’Day

Author’s Note

Introduction

Part One:‘What About Ye, Soldier Boy?’

Part Two:Bloody Belfast

Part Three:The Other Killing Grounds

Part Four:Going Back, Looking Back

Afterword

Roll of Honour

Select Bibliography

Copyright

No matter how well trained you are, as a professional soldier; no matter how hard you think that you are; no matter how impervious to emotion the civvie thinks you are, you never get over the sight of seeing your mate’s life blood spill onto the street.

Soldier, Light Infantry, Belfast

To have allowed over a thousand British soldiers’ lives to have been lost in our own back yard and to have many, many more injured is criminal.

Pete Whittall, Staffords

So I saw this kid who was about 6 years old, sitting on his doorstep with his little puppy and I thought I would go and sit next to him. I asked him: ‘Is that yours mate?’ ‘Yes,’ he replied, but without ‘Brit bastard’ at the end which was a bonus and a change. ‘It’s a lovely puppy; can I stroke him please?’ I asked. His reply shook me and stays with me to this day and summarises the Troubles for me; ‘No, because me ma will beat me if I let you,’ he said, looking at me with the saddest eyes.

Craig Laidler, Royal Tank Regiment

The only time I ever felt let down was when our Government started to concede ground to the terrorists, and we became an embarrassment to their political aspirations. While they were busy back-slapping each other for a job well done, they were at the same time slapping us in the face and backsliding against us. They had us over there, trying to do our jobs with one hand tied behind our backs. As you know, there were so many rules enforced on us, that it was almost impossible not to break them and do your job effectively.

Tom Neary, Royal Artillery

But, Ken; it wasn’t really a war, was it?

John Humphries, BBC

THE VOICES OF THE BRITISH ARMY IN NORTHERN IRELAND

Mick Pickford; Ken Ambrose; Andrew Bull; Haydn Davies; Paddy Lenaghan; John Swaine; Andy Thomas; Mick Hill; Ernie Taylor; Eddie Atkinson; Alan Borthwick; Brian Roberts; Jim Seymour; Tim Marsh; Colin Berry; ‘Onion’; Craig Laidler; Darren Kynoch; Gordon Vacher; David Harding; Kelvin Brown; James Henderson; David Hardy; Tommy Clarke; Frenchie; Dougie Durrant; ‘S’; James Reeves; John Wood; Josef Jurkiewicz; Kevin Stevens; Lawrence Jagger; Marty RGJ; Mick King; Martin Webb; Ken Wharton; Mick Potter; Neil Chant; Steve Wilson; Bill Jones; Big Stevie; Von Slap; Steve Crump; Nigel Barnes; Nigel Glover; Steve Norman; Paul Crooks; Pete Whittall; Phil Hyslop; Richard Drewett; Richard Nettleton; Rob Hughes; Stuart Mallinson; Simon Bromige; Robert Hutton; Simon Richardson; Stephen Durber; Tom Neary; Glen Espie; David Mitchell; Colin ‘Jim’ Bowie; Roy Davies; Ronnie Gamble; Gavin; Lee Sansum; James Kinchin-White; Jimmy McMaster; Alex, UDR; Micky Lee (71); and the anonymous contributors.

THE TWENTY-ONE SOLDIERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES BEFORE ROBERT CURTIS

TPR Hugh McCabe

14/08/69

Killed by friendly fire, Divis Street, Belfast

L/CPL Michael Spurway

13/09/69

Shot in controversial circumstances

CFN Christopher Edgar

13/09/69

Violent or unnatural causes

L/CPL Michael Pearce

24/09/69

Violent or unnatural causes

RFN Michael Boswell

25/10/69

RTA involving rioters

RFN John Keeney

25/10/69

Killed in same incident

MJR Philip Cowley

13/01/70

Died on duty

GDSM John Edmunds

16/03/70

Drowned

PTE Peter Docherty

21/05/70

Killed accidentally

SGT James Singleton

23/06/70

Died on duty

PTE Victor Chapman

24/06/70

Drowned

PTE David Pitchford

27/06/70

RTA

S/SGT Peter Sinton

28/07/70

Violent or unnatural causes

PTE Thomas Wilton

22/10/70

Died on duty

PTE John Proctor

24/10/70

RTA

MJR Peter Staunton

26/10/70

Violent or unnatural causes

PTE Brian Sheridan

20/11/70

RTA

TPR James Doyle

24/11/70

Cause of death unknown

SGT Thomas McGahon

19/01/71

RTA involving rioters

CPL James Singleton

19/01/71

Killed in same incident

SGT John Platt

3/02/71

Thought to have been shot in an ambush at Crumlin

FOREWORDBY MAJOR ANDREW MACDONALD, LATE KINGS OWN BORDER

I met Ken in 2007 through a mutual friend – the late Lieutenant Colonel Geoff Moss, Kings Own Border– whose tragic death from a sudden illness in early 2009 left us very shocked. Geoff knew that I’d done several Op Banner tours and that I could help Ken with his new book: A Long Long War. Like many, I had countless memories from my seven tours as a Kings Own Border officer but had not taken the trouble to make any sensible records that would exist long after I had forgotten the detail.

I began to understand that Ken’s interest was more than that of an author: it was a passion. He possesses a rare ability to galvanise those of us that have stories locked away from experiences gained long before digital technology made it inexcusable not to record what goes on. He has this ability to seek out the latent storytellers who would normally be too modest to relate their experiences, then to draw out their experiences and record them. As an army we needed this catalytic process to help us write down what went on during the long campaign in Northern Ireland so that as we get more forgetful, those that actually did it – the front line soldiers and officers, rather than the official historians, politicians and generals - can record what actually happened. This book is published at a time when the spotlight is on both the Army and defence in general. Whilst the many conflicts in which the Army has been engaged in the era of ‘modern’ warfare differ greatly, the single common factor has been the soldier. And it is he (or she) that will always bear the greatest burden. Without the courage, doggedness, humour and sheer bloody-minded determination of our fighting men, our Armed Forces would not have the reputation that they so richly deserve. And in this context, we must never forget the other uniformed services in Northern Ireland. Those qualities, so wonderfully revealed in this book, are still displayed today. Indeed, the impediments that our soldiers face in current conflicts – whether for political or economic reasons or through sheer bureaucratic bungling – are, I suggest, very similar to those that we experienced when deployed on Op Banner throughout the campaign.

For me, Ken’s books represent one of the best records of what actually went on at ground level since I read George MacDonald Fraser’s Quartered Safe out Here. Ken’s efforts to pull these stories together rightly deserve to put his books in that category. This book is a tribute to all those who served and his painstaking efforts to record the voice of the soldier should be richly rewarded. So even if you come from a non-military background, please read on. You can dip in and out but on every page there’s something that you may not find in an official history and you certainly won’t be getting military fiction.

I am particularly honoured to have been asked to write the Foreword for Bloody Belfast; thank you.

PREFACE BY MICK O’DAY

I first spoke to Ken Wharton on the telephone in 2007 after a mucker in my regimental association pointed him in my direction, as someone who might be able to help put a book together about the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Ken, then a completely unknown, unpublished author, outlined to me in just a few minutes his idea to amass stories written by former British soldiers; stories told from the viewpoint of the ordinary squaddie on the streets of Northern Ireland; often then very young men, who between them faced 30 years of atrocities head on; stories never told before.

Like me, he knew what great evil had been raging throughout that land but these were events I’d long ago consigned to grey memories of a distant past life. Ken was different. From this very first call, it was clear to me that he wanted to do something about it and I knew I was dealing with a straight-up guy who cared deeply about what had passed during the Troubles. From the outset, he made it plain that this book would include no neutral commentary. His intention was to give the ordinary British soldier a voice and let them tell the story, warts and all.

Many would consider this book an impossible task, bearing in mind that these 300,000 former soldiers are now scattered throughout the world. What followed was a roller coaster of activity as former lowly Rifleman Wharton unleashed his passion, his energy, his talent and his total commitment on the world that links former soldiers, civilians now, as they go about their daily lives. No one told him that this would be difficult, if not impossible – had they tried, he wasn’t listening anyway. Blind enthusiasm, a belief in his purpose, a book, which as yet had no content, no name and not even a glimmer of an interested publisher, propelled this guy straight through or over all hurdles placed before him, in a way I’ve rarely witnessed. I had very little doubt that he’d succeed.

My mate Ken, former ordinary British soldier, was now a published author and he could be seen signing books, delivering presentations all over the UK. Popping up on the telly, the radio and in national newspapers, sounding just like the professional author and truly expert voice of the British squaddie that he deserves to be seen as; not by virtue of military rank or social position but by sheer commitment to the task in hand.

If you ask him, he’ll tell you that it was I who in some way made it possible; but that’s not really what happened. Ken Wharton did it by himself; driven by a deep belief that the telling of these stories, was a necessary footnote to the history of violence in Northern Ireland; a job that just has to be done.

(Mick O’Day is a former IJLB, Scots Guards and 3 Brigade Photographer.)

AUTHOR’S NOTE

When I wrote A Long Long War; Voices from the British Army in Northern Ireland, 1969-98 I was fortunate enough to be invited onto five different BBC Radio stations to discuss my book and the impact upon those of us who served during the troubles. On one occasion, the esteemed John Humphries on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme said to me: ‘But, Ken; it wasn’t really a war was it?’

I invited him to ask any of the 300,000 who served during Op Banner – the longest single British Army operation in its long and glorious history – if it was a war. I repeat that offer to him and I ask you, the reader, to speak to David Hallam (RGJ), Eddie Atkinson (Green Howards), David Dews (Royal Regiment of Fusiliers), Phil Winstanley (Royal Army Medical Corps) or any one of thousands of former soldiers who witnessed the horrors of Northern Ireland; ask them if it was a war or not.

True, it wasn’t the profligate, mass slaughter of the Somme; it wasn’t the orchestrated mass battles of El Alamein, or Arnhem, or the Reichswald; it wasn’t the major firefights of Goose Green or Mount Longdon or Tumbledown; but it was a war. It was a war fought largely in the shadows, against an increasingly professional and well organised terrorist army. It was a war where a soldier would be shot as he ran to close a gate and where soldiers would be cut down in their beds and their places of rest. Make no mistake; Northern Ireland was a war.

In the early hours of Sunday 8 March 2009, I was awakened by a text; it was a message from Tim Marsh, a Green Jacket friend of mine and it alerted me to the fact that something awful had taken place in Northern Ireland. I put on the television and learned of the killing of two soldiers at an Army base in the land where we had all hoped that the peace was a lasting one.

The following morning, the world heard the names of the two dead soldiers; Sapper Mark Quinsey, 23, from Birmingham, and Sapper Patrick Azimkar, 21, from Wood Green, North London. Barely had we begun to mourn, when dissident Republicans murdered PSNI officer Stephen Carroll (37) at Craigavon. He became the first policeman to be killed since Constable Frank O’Reilly, on 6 October 1998, fatally injured in a blast bomb attack by Loyalists in Corcrain Estate, Portadown. My friend and comrade Tommy Clarke, whilst shooting a TV documentary only a week earlier, had warned that it wasn’t all over. Indeed, I had been very cautious in my hopes for peace following my return to the Province in late 2008.

Whether or not this was the work of the so-called Real IRA, responsible for the slaughter of the innocents at Omagh in 1998, or the equally outrageous Continuity IRA or an as yet unnamed Republican group is entirely irrelevant. That some eleven years on, with a hard-won peace still paying dividends, any group, under whatever label, could seek to revive the killings all over again is simply beyond my comprehension. I have never professed to be an intellectual; my writing was described as the ‘simple prose of the soldier-scribe’. I am, however bewildered, bemused – not shocked – and appalled that there still exists, within the Republican community, a group of people determined to revisit the Troubles on a country still in the recovery phase following 30 years of insanity.

INTRODUCTION

On Thursday 14 August 1969, I was a young soldier; only nineteen, with so little experience of this great big world watching a TV in a NAAFI club at a barracks in the deep south of England. When you are a Leeds born and bred Yorkshire boy who, prior to taking a train to Aldershot to join up in early 1967 had only left the confines of God’s own county three times, then Hampshire was the deep south. It showed scenes – in black and white, of course – of a drama being played out in a country so close you could spit across the Irish Sea and hit it, and yet, it was a country of which I had never heard. That was, until it thrust itself into our newspapers, our televisions, our radios and soon enough, into our collective psyches.

That country was Northern Ireland. A country which was to have a personal effect on my life for several years; an effect on all our lives for almost 30. It will, sadly, for many be a place synonymous with violence, tragedy, intolerance, suffering and sudden death. Did I say that it had a personal effect on my life for a few years? I will be haunted forever by the suffering of my comrades and those wonderful, innocent people of Northern Ireland who neither sought nor supported terrorism.

The net result upon the lives of the people living in both England and Ulster was the loss of over 1,300 military lives, over 300 Police lives, and well over 4,000 lives in total. It also cost billions of pounds in destroyed property; and the emotional and psychological cost that can never be measured. A close friend of mine – and, like me, an ex-soldier – said: ‘We were part of the solution, but we were also part of the problem.’ I’m not sure that I can agree entirely with what he said, though I do agree that we were certainly part of the solution and the peace that was so hard won. The change that was won over those years of struggle with the IRA and the other paramilitaries was paid for with the blood of British troops and Ulster policemen. That same blood which stained the streets of the Ballymurphy Estate, the Turf lodge, Twinbrook, the Ardoyne, the Creggan, the Bogside and the fields of Ulster, ultimately paved the way for freedom, the removal of fear and the constant threat of terrorist violence that a new generation of Northern Irish no longer have to face.

Let us not forget that the other 3,000 deaths represented an appalling civilian tragedy, as the great majority of the fatalities were not paramilitaries. The innocent bystanders included those caught in the crossfire of the bullets or the indiscriminate terrorist bombs, or those slaughtered because they gave the wrong answer to that most perverted, most evil of all questions: ‘Are you a Protestant or a Catholic?’

I recently visited that country for the first time in over 30 years as I had many ghosts to lay to rest. I am pleased to report that although the Black Mountain continues to dominate Belfast and will for millions more years, some things have changed. There are more cars and many of the old blackened terraces of the Lower Falls have been replaced by newer housing. Indeed, the dump that was the ’Murph is changed beyond all recognition; the gardens are tidier, there are no old fridges or cookers in the front gardens and no rusting Vauxhall Vivas or Ford Anglias, propped up on bricks. The outsides of the houses are cleaner and the ubiquitous packs of stray dogs that chased our PIGs around the ’Murph, or Turf Lodge, or Andersonstown, now appear to have gone to that great doggie heaven in the sky. However, when I walked around the Creggan heights in Londonderry, or Derry, or ‘stroke’ city, whilst the yellow paint now gleams and covers up the scrawled ‘We stand by the IRA’ slogans, the underlying menace and threat are still there. Moreover, one does feel that one is in a foreign country and the green painted post boxes, sand stores and the plethora of Irish Tricolour flags give the impression that one is actually in the Irish Republic and not on a British street.

The accents are different in Glasgow and Edinburgh but it is still Britain; the accents are different in Cardiff and Harlech but you are still in Britain. The accents vary in Ulster also, but one-third of the population feel that they are Irish first, second and third. Perhaps when the historical borders – some say arbitrary – of Northern Ireland were drawn up, some of the six counties should have stayed within the Irish ‘Free State’, and certainly there is a case for Co Armagh to have done so. Whatever the rights and wrongs of this delineation, by 1969, it clearly wasn’t working and, whether or not the popularly held views about discrimination were fact or naively held belief, the Army had to go in. On that wonderfully hot August day in 1969, British squaddies in their shiny tin helmets, denim uniforms, SLRs with fixed bayonets at the ready, were deployed onto the streets of the Falls, the Divis, the New Lodge, the Ardoyne, the Gobnascale, the Waterside, the Bogside and the Creggan. Their only knowledge of civil unrest was a brief exposure to an Army training film ‘Keeping the Peace, Parts 1 and 2’. Who would have guessed, who could have guessed, that almost 30 years later, those same soldiers or more likely their successors would still be on those same streets, still fighting, by then, a second generation of terrorists?

By the end of that first day’s deployment, five people, including nine-year-old Patrick Rooney – killed by a stray (possibly) RUC round and the following evening the first of nearly 1,300 British troops would be killed as he visited his parents’ home in Whitehall Row in the Divis Flats area. Trooper Hugh McCabe (20) was on home leave from the Queen’s Irish Hussars based in West Germany when he was also killed by a ‘stray’ round. After that, it never really stopped and even after the ‘final’ ceasefire, the self-styled Real IRA saw fit to butcher another 29 innocents in the sleepy market town of Omagh in Co Tyrone.

The IRA and INLA took their terror war farther afield and British blood – military and civilian – was spilled in Belgium, Holland and Germany. It stained the streets of London, Deal, Derby, Litchfield, Yorkshire, Eastbourne, Northumberland, Warrington, Guildford, Birmingham and Tadcaster. There was never a let up as the terror gangs sought to sicken the British public into putting pressure on their Government to withdraw from Ulster. I do not class myself as a particularly intelligent person, but I confess my inability to comprehend how the bombers of the ‘Mulberry Bush’ in Birmingham or the ‘Horse and Groom’ in Guildford could sit and drink amongst the revellers and then walk out, having planted a bomb, fully cognisant of the death and maiming that would follow amongst those happy, smiling faces. As each atrocity outdid the previous one, as outrage after outrage followed, the terrorists felt that they could push the British over the emotional edge and make them demand their Government pull out of the North. What they forgot and what an invaluable historical lesson they overlooked was the willingness of the British to stoically bear anguish. After all, an Austrian house painter had tried much harder than them in 1939 and had, as posterity records, failed spectacularly. Most people would agree, particularly those who survived the Blitz during those dark days of 1940 and 1941, that the Luftwaffe was a much more terrifying enemy.

This book, in the main, covers the IRA’s killing fields of Belfast, where indeed, the bulk of the Army’s casualties took place, but I would be foolish to ignore other parts of the Province. There are too many other places where the IRA/INLA and other terrorist groupings practised their evil art and I will step outside the capital in Part Three.

I was asked, during the course of writing this book, what my opinion was of the IRA. I replied that I condemned them – as indeed I condemn all terrorist organisations – for their cowardly attacks and absolute contempt for life. There is, however, one aspect I have never considered and sometimes reproach myself over. Did they grieve for their dead; did they shed tears for their ‘volunteers’ killed by their own bombs or by our counter-terrorist methods as we did for our fallen comrades? I have often compared the IRA/INLA and the others to psychopathic gangsters who would have been criminals, thugs and murderers even had the Troubles never happened. But did they grieve as we did? Perhaps we will never know.

Over the long and tortuous course of the Troubles which dragged on for almost three decades, the decent people of Ulster – Protestant and Catholic alike – had to contend with almost daily mayhem and death. Those of us fortunate to be on the mainland saw only what the Government of the day allowed us to see. At the announcement of the death of a soldier or a policeman, most of us shrugged and thought ‘that’s a pity’ and then moved on. For the people of the Province and those who had lost a loved one, there was no moving on and Wilson, Callaghan, Heath, Thatcher, Major and Blair continued to send out more soldiers to the ‘twilight zone’ of Northern Ireland to be quickly forgotten. I swear that through my writing, I will never allow that to happen.

PART ONE

‘WHAT ABOUT YE, SOLDIER BOY?’

Northern Ireland was a shit-hole; the IRA and the Prod extremists saw to that, but there were decent people there and we had to go in for their sakes. For every one bastard, there were at least twenty or more decent ones who probably hated the paramilitaries even more than we did, but didn’t dare say so.

Private ‘W’, Royal Regiment of Wales

I do recall on a lighter note one incident that made me smile; a woman came up to me in the street and asked if I’d speak to a very young girl who had never seen a soldier. This young girl was from Canada and just maybe there are not too many soldiers on streets there. I did speak to this very young girl and I think that I made her day but, anyway this made me smile a great deal.

Nigel Glover, Royal Artillery

Too many of this wee Province’s citizenry were/are indifferent to the sacrifice made by HM Forces during Op Banner; but there are those who remember and will always be grateful.

Alex, UDR

On 14/15 August 1969, British troops were deployed onto the streets of a part of the United Kingdom for the first time – other than during the exigencies of wartime – since the General Strike of 1926. In Northern Ireland, law and order had finally broken down. The excellent Lost Lives states that, prior to that fateful day, eight people had been killed, including several some three years before the ‘recorded’ start of the Troubles. It is not the brief of this oral history to cover this period and, for the sake of a beginning, it must start the day before, with the first deaths in what the Ulster folk call the ‘wee hours’ of that August day.

Herbert Roy (26) from the Loyalist Shankill Road area became the first of five people to lose their lives that day. He was involved in rioting in the Divis Street area of Belfast and was shot and died of his wounds around 30 minutes after midnight. Almost simultaneously, little Patrick Rooney (9) was shot and killed in his own bed in the Divis Tower by a stray round. The author, a young and naive soldier, watched with horror and disbelief the TV interviews conducted with his distraught parents; the black and white pictures of a devastated, yet calm looking working man describing how he had to scrape part of his little boy’s head off the bedroom wall with a spoon. That interview, those words and the horrific imagination which accompany it will follow this author to his grave. Little did he or any of the watching world realise that many, many more grieving parents would suffer the same way before the Troubles finally claimed their last victims.

Private Hugh McCabe, a British soldier home on leave and merely observing the rioting was shot and killed in Whitehall Row, also in the Divis area. He was buried with full military honours by his comrades from the Queen’s Irish Hussars and, by the end of that fateful year, 139 days later, a further five British soldiers would also be dead. Almost seventeen months after the troops had gone in, Gunner Robert Curtis was shot and killed in Lepper Street, Belfast on 6 February 1971, along with his comrade, Gunner John Laurie who died six days later from his wounds. Popular convention has identified Curtis, whose pregnant widow gave birth some months later, as the first soldier to be killed in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. I believe that there is evidence to the contrary and that Gunner Curtis was the 22nd soldier to die.

By the end of the following month, three more soldier’s families would have received the dreaded visit by their loved one’s CVO (Casualty Visiting Officer), or equivalent, to inform them of the premature ending of a young life. On 13 September Lance Corporal Michael Spurway of the Royal Corps of Signals was killed in a ‘friendly fire’ incident and the very same day, REME Craftsman Christopher Edgar would also be dead. The circumstances surrounding his death remain highly confused and highly controversial and I am permitted only to say that he died from what the MOD refers to as ‘death by violent or unnatural causes’. Eleven days later – and here the author knows definitively the cause of death – Lance Corporal Michael ‘Mickey’ Pearce of the Royal Green Jackets became the second soldier to die under this ‘definition’.

A month later, two young Jackets Riflemen, Michael Boswell and John Keeney were killed in a riot-related road traffic accident (RTA) in the Belfast area. 1970 would continue in the same vein and eleven more regimental CVOs would make that sad journey to a house in Manchester or Leeds or London or any one of those places we all called ‘home.’ The reality was, of course, that the Army and your new-found comrades were your actual home.

Before that fateful day in the Ardoyne ‘interface’ area where IRA gunman Billy Reid shot and killed Gunner Curtis and fatally wounded Gunner Laurie, a total of 21 British soldiers had lost their lives through a variety of causes. Whatever the MOD statisticians claim, Robert Curtis was the 22nd soldier to die in Northern Ireland, not the first. Some will argue against this contention, but there were 21 families on the UK mainland who received the tragic news of a loved one’s death many months before the Royal Artillery CVO made his fateful visit who would agree with me.

Reid himself would be killed some three months later by a sergeant in a Scottish regiment after an attempted ambush in, ironically enough, Curtis Street, at the junction with Academy Street, north of Belfast’s city centre. His short, violent and murderous career would end around 800 yards from where he had bloodily written his name in IRA ‘folklore’.

The British soldiers were mostly deployed onto the streets of Belfast and Londonderry, but also in Omagh, Portadown, Newry and countless other places. They were sent in to fill the power vacuum created by the partial retreat of the outnumbered, beleaguered RUC. They were greeted, in the main by cheering Catholic families with cups of tea, biscuits and flowers and quickly – innocently and naturally – assumed the role of liberators. The same greetings were also to be found in the Loyalist or Protestant areas as these communities saw the Army as a buffer between themselves and the Fenians. Were the soldiers confused? Of course they were, as they had to appear to be the saviours, simultaneously, of two differing communities with diametrically opposing religious and political views.

It is certainly true that the Catholics eventually saw them as oppressors as their ‘honeymoon’ period with the ‘Tommies’ came to an end, probably about the same time as the other community began calling them ‘Taig lovers.’ Small wonder, that the ordinary squaddie saw himself as ‘piggy in the bloody middle’. These feelings were experienced no less by the young officer classes. For many there, including the author, the streets of Belfast and Londonderry were not a million miles away from their own streets and homes. One Green Jacket remarked, when he first saw the housing of the the Markets area: ‘Jesus Christ; I’m bleedin’ ‘ome!’

As the supply of cups of tea, plates of sandwiches and biscuits began to dry up as the soldiers patrolled the Ballymurphy Estate, the Turf Lodge, the Ardoyne, the New Lodge, Tiger Bay in Belfast, Creggan, Bogside and Gobnascale in Londonderry, so it was soon replaced by other, less savoury and certainly less edible, objects. The soldiers were spat at, had urine and faeces – human and canine varieties – hurled at them; had used sanitary towels thrust into their faces, had women break wind in their faces as they rested on their haunches on street corners. Soldiers had had dead cats and soiled baby’s nappies hurled at them as they patrolled. Through all this incredible provocation, they remained, in the main, professional and composed, which reflected the high quality of training a British soldier must undergo before being allowed outside the barracks gates.

One young soldier from the Royal Green Jackets told the author of a moment when he went into a sandwich shop – or ‘choggie’ as generations of soldiers would know them – and ordered a salad sandwich. The assistant picked one and carefully opened it and asked, ‘Ye want anythin’ on this, soldier boy?’ When the Jacket asked for salad cream, she spat onto the contents and passed it to him with the words, ‘On the house, soldier boy.’ Soldiers by now, were either declining cups of tea from Catholic households, or pretending to drink them, suspecting that they may have been spiked with all manner of toxic or dangerous substances. The breakdown in the relationship between the ‘liberators’ and the ‘liberated’ was starting to gather momentum; it would, inexorably and, perhaps, inevitably, lead to a complete and irrevocable deterioration. Although the following would occur some years afterwards, a Kingsman spoke to me of an incident which involved one of his comrades, Lance Corporal Andy Webster. Both soldiers of the King’s Regiment were based in the Andersonstown/Turf Lodge area. Andy Webster had bought his copy of the Daily Mirror from ‘Andersonstown News’ every day since the tour had started some months earlier. One morning he went in, and the newsagent, albeit politely, informed him that he could no longer sell to him or any other British soldier. It does not take a genius to work out that the local IRA commanders had warned the man off. Sadly, not long afterwards, this popular young NCO would be another casualty statistic. Webster was killed in action in Ardmonagh Gardens in the Turf by an IRA bomb on 19 May 1979. Another name for the British media and public alike to gloss over.

From that early ‘liberation’ period, successive tours of squaddies would be aware that they were persona non grata in parts of the United Kingdom. They would know that, in the Catholic/Republican areas, shopkeepers, innkeepers and the like would refuse to serve them and that, unless they were there in uniform, with brick, platoon or Company comrades, these were locations to avoid.

Up until the death of Gunner Robert Curtis the death of a soldier was still a rare occurrence, but afterwards, the floodgates would open. 32 days later, on the evening of 10 March 1971, three young Scottish soldiers, all related, would be lured to their deaths in a sleepy little village just north-west of Belfast. Despite the dangers, unarmed soldiers in civvies, with no personal protection weapons, would still, irresponsibly, be allowed into the city centre and other adjacent ‘safe’ areas of a night time to indulge in the squaddies’ second favourite pastime. Whilst drinking near the Cornmarket in the Markets area of Belfast, two young brothers and their older cousin were picked up by seemingly Loyalist women with the offer of a party.

The three soldiers – according to eyewitnesses, the worse for drink – got into a car with the women, still clutching their glasses half full of beer and set off for an evening’s continued revelling. Just north-west of the city, at White’s Brae, Squire’s Hill, Ligoniel, on a lonely mountain road, the car stopped. Apparently the three young Scots lads got out of the car for a ‘pee break’ and, whilst they stood, facing away from the road, several members of the IRA who had lain in wait approached them with revolvers. Two of the soldiers were shot in the back of the head and the third was shot in the chest as he turned. The bodies were found the following morning by children; two of them still clutched beer glasses in their lifeless hands. The three were John McCaig (17) his brother Joseph (18) and their cousin Donald McCaughey (23); all were from the Royal Highland Fusiliers and were from Ayr and Glasgow.

The then Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, a senior member of the Heath Government said, in a statement relating to the perpetrators of these first killings of off-duty soldiers: ‘… it is a small minority of armed, ruthless men whose strength lies not so much in their numbers as in their wickedness.’ These would not be the last soldiers to be killed whilst off duty. The City of Belfast Coroner stated that the murders were ‘one of the vilest crimes ever heard of in living memory.’ (Belfast Telegraph). That Coroner could not have possibly imagined at the time that this was but the first of a whole series of ‘vile’ crimes which would be perpetrated by both communities’ paramilitaries over the course of the next near 30 years.

One of the alleged killers, IRA member Patrick McAdorey, was himself later killed. On 9 August he was shot in Brompton Park in north Belfast during anti-Internment protests, apparently in a fire fight with soldiers, although there is some speculation that, in the chaos, he may have been shot by Loyalists. Lost Lives suggests that McAdorey may have also been responsible for the death of another soldier that same day. Private Malcolm Hatton (19) of the Green Howards had been shot and killed earlier during intense gun battles with the IRA in the Ardoyne area. That period of utter insanity, 9-11 August 1971, cost the lives of no less than 23 people; 20 of the deaths were in Belfast. The fatalities included two British soldiers and the first UDR man to be killed by the IRA. Paul Challenor (22) of the Royal Horse Artillery was fatally wounded by an IRA sniper in Londonderry and died shortly afterwards of his wounds. The UDR man was Winston Donnell (22) who was shot and killed by the IRA near Clady, Co Tyrone.

The gloves were off; the IRA had demonstrated, in their own evil fashion, that they were not the IRA of old – amateurs, armed with World War II German Mauser rifles and stolen TA Lee Enfields – but were now practised, professional and cold-blooded killers. They had the deaths of, officially, six soldiers to their ‘credit’ and unofficially were involved in most of the deaths of all 29. They were now starting to make a mark. Professional and cold-blooded as they already were, they would only get better at doing what they did best, killing members of the Security Forces.

Even the mass, continual rioting followed a set pattern; gangs of younger teenagers would set light to hastily built barricades and then pour a hail of rocks and stones on the soldiers and RUC. Behind them, older men would then run up and hurl petrol bombs and empty glass bottles; the soldiers hated the bursting bottles and the razor edged sharp shards of glass which showered over them. Behind this second rank, would be the shadowy IRA gunmen who would then order the front two ranks to part, like Moses parting the Red Sea, and then either open fire on selected soldiers or simply pour indiscriminate automatic fire at the massed troops.

By 1971, senior Army men knew, before the man on the ground, that the concept of protecting the Catholic communities was dying. The writing was on the wall – in more ways than one. The proliferation of signs demanding that the Brits left was evidence of this. ‘Don’t ball-lick the Brits; fight ‘em’ and ‘We stand by the IRA’ could be seen on every street corner in every Republican enclave in Northern Ireland. The long favoured open riot square formation was out; it had worked in Singapore, Hong Kong and Malaya, but the boyos were distinctly unimpressed. Instead, a formation with riot shields which protected front and flanks, and, like the old Roman ‘testudo’ shield formations, overhead as well, was developed. This formation was protected by riflemen in flank positions whose job it was to take out the gunman or the bomber. The addition of the famous snatch squads which employed the fastest runners to suddenly break through their shields and literally snatch ringleaders and drag them back behind the lines proved invaluable time and time again.

Later, in 1972, the controversial plastic bullets made it easier to target and temporarily disable people before the snatch squads were deployed. For those who were not caught at the time, where possible, video footage was taken of all the rioters’ activities so that they could be identified, traced and picked up at a later date. Another useful innovation were the mobile patrols within Belfast City Centre with the introduction of random VCPs (Vehicle Check Points). Buses were great fun for the soldiers, eager for some payback after all they had endured, where you could spend half an hour ‘P’ checking all the people on a crowded bus and then move location to start all over again with a line of cars. It is a fact that by constant 24-hour patrolling the Army limited the opposition’s ability to plan, to move people and equipment and to set up operations against them.

The need to patrol and dominate all areas constantly was always there. The patrols were up to four hours long and in the worst areas it was hard targeting for all of that time, so if the soldier was not in a fire position he was running and weaving to one. Patrol routes and timings were constantly changed to avoid forming any sort of pattern. A lot of talk went on about building a wall around the ‘hard areas’ and containing them and although this would have presented less risk to the soldiers it would also have created further no go areas, with a complete breakdown of law and order as a consequence. Another consideration was that maybe 95 per cent of the people in those areas did not deserve to be abandoned to the rule of the gun and terrorism. This had already happened in some parts of Belfast by 1972 and it was only as a result of mounting Operation Motorman that these areas were reclaimed from the terrorists. The pity of it is that the IRA had learnt from the post-Internment gun battles of 1971 and never again came out on to the streets to take on the Army. ‘Operation Motorman’ was a walkover.

From this point onwards, the pattern throughout the Province would remain largely the same, certainly concerning shootings. Instead of the ‘traditional’ fire fight, a lone IRA or INLA gunman would stalk the soldier using ‘dickers’ (a concept which will be explained through the soldiers’ own words) or take over a house or a shop, knowing that even irregular patrol patterns would soon bring a soldier into their scopes. The deaths of Blues and Royals’ Troopers Thornley and Dykes, shot and killed at the security gates at Andersonstown RUC station in April 1979 typified this approach. IRA gunmen had taken over a barbers’ shop opposite the station and waited until the two men were vulnerable at the open gates. The deaths of Kingsmen Shanley and Rumble, which took place in the Ballymurphy Estate in the same month are another example of these hit and run tactics. On this occasion, IRA members took over a house in Glenalina Gardens and a sniper fired shots from an upstairs window and killed both men; Steven Rumble died of his wounds eight days later. Murals on the ’Murph depicting a group of IRA gunmen – and women - in green Parkas, armed with assault rifles raiding as a group are certainly misleading.

The concept of the ‘lone gunman’ was also a bit of a misnomer, as in addition to the ‘dickers’ who reported on patrol movements, other supporters would be on hand to try and get weapons out of the area into the myriad IRA safe houses. The gunman would lie on a blanket and shoot at the soldiers from the prone position and, if hit, his supporters would drag the wounded – or dead – terrorist away on the blanket, along with the weapon and important forensic evidence. Another tactic was to get to a pre-arranged ‘safe house’ after a shooting, where a bath full of water would be ready for the gunman to jump straight into, in order to attempt to wash off the forensics.

Over three decades, generations of soldiers had to be based, safely quartered, fed and watered right in the very areas where they would be needed to make most impact. On the mainland, particularly across the south-east, literally hundreds of Army camps, some as old as time itself, others remnants of an Allied Army in the mid-40s, proliferated. In garrison towns like Tidworth, across Salisbury Plain, in Army towns like Aldershot, Camberley, Winchester, Colchester and the like, a barracks could be found without much searching. In Yeovil in Somerset, the Army had a ready-prepared former US hospital camp, one that, built in the days of segregation, had been for blacks only. That, however, was not the case in Ulster, and the Army had to find bases for the 30,000 troops at the peak of maximum deployment. The Mission Hall in the Markets, Grand Central Hotel, in Royal Avenue, Fort Monagh on the Turf Lodge, Flax street Mill, Ardoyne, North Howard Street Mill, Fort Jericho (also known as ‘Fort Whiterock’ in West Belfast, Albert Street Mill, Falls area, Henry Taggart Memorial Hall and Vere Foster school on the ’Murph are just a few names that will evoke a host of memories for those who were based there.

The IRA attacked the Security Forces in the Ulster countryside as well as on the streets of the urban areas. However, much of the violence and killings took place in the streets and town centres and suburbs of the two main urban conglomerations of Belfast and Londonderry. The Falls, Divis Street, New Lodge, Ardoyne, Tiger Bay and Short Strand were traditional, terraced workers’ housing. The Ballymurphy Estate, Turf Lodge, Andersonstown and Twinbrook were contrasting modern, postwar Council housing estates. I trust that the following analogies will suffice even for the reader outside of my home town of Leeds. I grew up in the terraced slums of Hunslet, a mirror image of the Falls, Ardoyne and New Lodge etc; I was then nurtured in the late-1950s council housing of the sprawling Swarcliffe and Seacroft Estates, which, in turn, were similar to the Turf Lodge and the ’Murph. Can the non-military reader now imagine that soldiers and policemen were being shot and blown up in their dozens in Sidey Street, Hunslet or Dennil Road, Swarcliffe? Imagine soldiers being machine-gunned to death on the York Road, Leeds as the three Green Jackets were on Crocus Street in 1982. As I look around Leeds or occasionally around Manchester, York, Liverpool or Newcastle, I find it so difficult to imagine a terrorist organization, armed with largely American-financed weapons, being able to kill both police and soldiers with the same apparent impunity.

If the reader will indulge my analogy further; try and imagine how the following Leeds boys might have felt, viewing the same types of streets and estates in Belfast and Londonderry with which they would be so familiar. Robert Pearson (Coldstream Guards, KIA 20/02/72), George Lee (Duke of Wellingtons, KIA 6/06/72), Paul Jackson (Royal Artillery, KIA 28/11/72), Michael Ryan (Duke of Wellingtons, KIA 17/03/74), Kim Macunn (Royal Artillery, KIA 22/06/74), Dennis Leach (Royal Marines, KIA 13/08/74) and David Wray (Prince of Wales Regiment of Yorkshire, KIA 10/10/75). Imagine the thoughts that went through the minds of Bradford boy John Swaine (Royal Artillery) or Morley boy Richard Smith (Duke of Wellingtons) both of whom, thankfully survived, as they also looked upon streets and estates so like their own? The British Army was fighting a war, albeit on someone else’s terms, but in a part of the United Kingdom, on what was, emotionally and physically, familiar yet alien territory. The hard streets and council estates of Belfast and Londonderry represented mirror images of the places most British soldiers had been brought up in.

Large parts of that area of south-west Belfast are very much alike, with the box-style, post-war council housing to be found in Twinbrook and Poleglass and on the Ballymurphy Estate. Regulation gardens, certainly during the Troubles, resembled scrap yards, with old fridges and washing machines or rusting hulks of cars propped up on bricks. Today, they are neater but are still the rabbit warrens of the early seventies where a fleeing gunman could always be sure of a welcome, feigned or otherwise. The Turf Lodge is similar, but with more of the smaller tower block flats or tenements and maisonettes that proliferated at one time in places like Leeds and Manchester. Farther north, above the Springfield Road, is the older, traditional terraced housing of the Ardoyne and New Lodge. Arranged in long, symmetrical rows, with reasonable proximity to Harland and Wolff – once the mainstay of labour provision for the area – they differed only from their Protestant neighbours on the Shankill and Crumlin Roads by virtue of the flags flown.

Make no mistake about it; the war in Northern Ireland was a particularly nasty one; it was, like all wars, a dirty one. It was a war fought largely in the shadows, where undercover soldiers would calmly shoot a known terrorist dead in a darkened Belfast back street. It was a war in which three or four young, heavily armed Catholic men, their heads full of sectarian and political hatred, would burst into the living rooms of off-duty UDR men, or RUC men, or prison warders, and slaughter them in front of their loved ones. It was a war in which men could walk into a crowded bar or restaurant and spray machine-gun fire at the occupants with no more qualm of conscience than if they had just killed a fly. It was a war where men could calmly sit amongst drinkers in a bar, leave a device designed to kill or maim and walk out without a conscience. And it was a war in which men could walk up to an innocent stranger and end his life simply because he was the ‘wrong’ religion.

PART TWO

BLOODY BELFAST

I was standing on a street corner in Belfast sometime in ‘71, when an old dear came up and gave me a bar of chocolate as her way of thanking me for trying to help. I did not want to take it as she was a pensioner, but as she said, she could not afford much but she could afford that. So I took it, and that felt better than any medal or commendation; that is why I was there.

Bill ‘Spanner’ Jones

Belfast was a place that we travelled through infrequently to get to other places; it held a sombre, hulking relevance. Its very reputation put everyone on their guard; clicked things up a notch. You did the job right there, or you died.

Stevie, UDR

FIRST INTO ULSTER

Roy Davies, Royal Regiment of Wales

We were sent from Lydd in Kent to Ballykinler for what we were told was to be a one month’s ‘adventure training’ period; some adventure! After two days at Ballykinler, we were deployed to Palace Barracks just outside Belfast city centre, ‘on standby to assist the civil powers’. On arrival at the barracks we could see that the skyline above the city of Belfast was all smoke and red with flame; flames high into the air just like after a big air raid.

At about 7pm on that hot night, we boarded our open-sided trucks and went in convoy into Belfast. We travelled through streets of burning houses, shops and factories. There was a cinema and no end of cars burning; one could hardly see for the flames and smoke. Our company arrived at the crossroads of Leeson Street and Northumberland Street and I was first out of the leading truck and followed by my mate Adams; I reckon I was the first soldier on the streets of Ulster. We didn’t know what to expect, but the locals were immediately friendly, brilliant in fact; they were Catholics and after some hours we had tea and cakes coming out of our ears.

The press arrived and started taking photographs, but we were told not to speak to them or answer their questions. We were in a position immediately in between the Catholics and the Protestants. The ‘B’ Specials were in the Protestant locations but came out on sorties from time to time. They scoured the area in Land Rovers that had turrets and .30 inch Brownings; they had the muzzles pointing towards us until we told them to ‘bugger off’. We wore fighting order, with scrimmed helmets and bayonets fixed, and had ten rounds of ammunition in our magazines and another ten in our pockets. I saw one platoon lead off into Northumberland Street in riot formation, apparently to ‘hold back the Prods’. I will, however, never forget the sight of some police helmets and shields lying about the ground as if a big riot had taken place. I picked up one helmet that had the side all bashed in, and the inside was awash with blood.

We slept the first few nights on pavements or anywhere that we could be warm and dry; safety wasn’t a problem then; everyone was so friendly and helpful, even to the supply of hot water for washing and shaving.

After a few days, we moved into Springfield Road police station and patrolled from there. We left for home after two or three weeks, but we were quite sorry to leave what was an enjoyable task of being a sort of ‘policeman’. In later tours we were always glad to get the hell out of the place and home.

Thus it had begun and though it didn’t happen for a while and even then almost imperceptibly, a change from cuppas and cakes to bullets and bombs would occur. This is how it began; cups of tea and cakes; read on and share the experiences of the soldiers who suffered the hatred and violence, caught in the middle of sectarian warfare and ending up as ‘piggies in the middle’.

NAVIGATING THE CROSSROADS

Infantry CSM

I hated the crossroads in Belfast. Not the crossroads on the outskirts, but the desolate late night ones in often wet, dark and windy, lethal Belfast city.

They were bloody awful places to have to cross over, because, if you think about it, you stand more than four times the chance of being shot at a crossroads. You were being observed from eight directions when you consider that a Belfast terraced crossroads has eight rows of houses with all their windows and doors. The derelicts, which were perhaps two houses out of every five, had a dark sinister threat of their own; snipers could get into derelicts and lurk and just bide their time.