28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

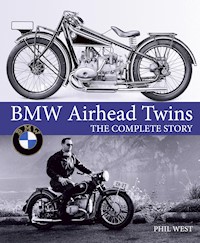

No motorcycle manufacturer is more closely associated with one type of engine than BMW: the air-cooled boxer twin or 'airhead'. It was included in BMW's very first motorcycle in 1923 and virtually every machine the company made, of every type, from radical road bike to TT winner, to land speed record holder, to 1970s style icon and even to the creation of an all-new adventure bike class with the R 80 G/S, right up to the mid-1990s. Phil West celebrates the success of the BMW airhead twin motorcycles. This book, with over 290 photographs, includes a history of the company pre- and post-War; the personalities behind the development of the bikes; profiles of each of the 'R' bikes in turn, including detailed specification guides and production numbers. These wonderful machines are regularly celebrated and now BMW itself is harking back to them with an all-new series of machines.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

BMW Airhead Twins

THE COMPLETE STORY

Other Titles in the Crowood MotoClassics series

AJS and Matchless Post-War Singles and Twins

Matthew Vale

BMW GS

Phil West

Classic TT Racers

Greg Pullen

Douglas

Mick Walker

Ducati Desmodue

Greg Pullen

Francis-Barnett

Arthur Gent

Greeves

Colin Sparrow

Hinckley Triumphs

David Clarke

Honda V4

Greg Pullen

Moto Guzzi

Greg Pullen

Norton Commando

Matthew Vale

Royal Enfield

Mick Walker

Rudge Whitworth

Bryan Reynolds

Triumph 650 and 750 Twins

Matthew Vale

Triumph Pre-Unit Twins

Matthew Vale

Velocette Production Motorcycles

Mick Walker

Velocette – The Racing Story

Mick Walker

Vincent

David Wright

Yamaha Factory and Production Road-Racing Two Strokes

Colin MacKellar

BMW Airhead Twins

THE COMPLETE STORY

PHIL WEST

First published in 2020 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© Phil West 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 696 8

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Say ‘BMW motorcycle’ and most motorcycle fans will automatically think ‘airhead boxer twin’. The distinctive air-cooled, horizontally opposed, twin-cylinder engine layout has been so intrinsically linked with the legendary German marque that, for most of BMW’s history, no other manufacturer has even attempted to use it.

And what a history that is. From powering the very first BMW motorcycle in the 1920s to style icons, racing and record-breakers in the 1930s; from wartime workhorses to a new generation of luxury tourers in the 1950s and 60s; and from the first faired superbike in the 1970s to the creation of the original ‘adventure bike’ in the 1980s, BMW’s versatile airhead boxer was at the heart of them all. Consistently proving itself over the years, the engine became so beloved that, when BMW tried to replace it in the 1980s, a huge backlash ensued. It was quickly reinstated.

The backbone of the Bavarian marque was eventually ‘killed off’ in the 1990s, due mostly to environmental and regulatory demands, but its new oil-cooled replacement was deliberately as close to the original in terms of style and versatility as it could be. Even then it was not quite the end of the airhead. The iconic twin lives on today not just as a revered classic but also as a style icon that often forms the basis of numerous customs and specials. BMW regularly revisits the boxer back catalogue for its fashionable new retros and is currently developing an all-new air-cooled boxer twin, intended to be a big-bore cruiser rival to Harley-Davidson’s equally legendary V-twins.

The BMW airhead story is certainly a biggie, then, spanning nearly a century and touching almost every type of motorcyclist. It has proved to be a demanding one to tell, and the writing of this book would not have been possible without the assistance of BMW itself, particularly BMW UK and BMW Motorrad’s extensive archive in Munich. To them I give my thanks. Thanks are due too to my long-suffering and ever-patient wife, Sarah, who is my rock, and to my boys, Tom and Olly, not forgetting Sarah’s Dylan, who are my inspiration. They all helped make the writing of this a pleasure. I hope I have done it justice and that you enjoy it, too.

Phil West, motorcycle journalist, editor and author

INTRODUCTION

No type of vehicle is more defined and characterized by its engine than a motorcycle. Comprising, according to popular folklore, of ‘two wheels, an engine and not a lot else’, a motorcycle’s powerplant is not just its motive force, it also plays a major role in defining its image and character. It is its beating heart. The motorcycle owner is more than likely to know whether his or her engine is two- or four-stroke, its number of cylinders and their layout, and will probably even be familiar with the valve train, final drive system and state of tune. All those elements together give that ‘beating heart’ its character, create its appeal and encourage its fans and following. In comparison, how many car drivers would know much about the configuration of their four-wheeler’s motor?

Where would Harley-Davidson be without its signature air-cooled, push-rod, ‘potato-potato’ 45-degree V-twins, which have been the American marque’s staple since before the war? How about Ducati, legendary manufacturer of Italian exotica, which has been defined by its devotion to the Desmodromically-driven, 90-degree ‘L-twin’ since the early 1970s?

There are many more examples: historic British marque Triumph, although it has a recent tradition of in-line triples, is identified most with its classic, parallel twin, first created for the 1936 Speed Twin 500 and finding its ultimate expression in the iconic 1959 T120 R Bonneville. One of the Hinckley marque’s latest new bikes is a modern take on that Speed Twin.

Moto Guzzi, the ‘grand dame’ of Italian motorcycling, has been inextricably and uniquely linked with its characteristic engine layout – the transversely mounted 90-degree V-twin complete with shaft drive – ever since the 1967 V7. Today, thoroughly evolved versions of that motor, in both small (750cc) and big block (now 1400cc) forms, continue to characterize the marque.

But the one motorcycle maker that is more closely associated with one particular type of motor than any other is BMW, with its boxer twin. Although periodically using other types of engine, such as singles, straight fours and, today, parallel twins, transverse fours and even straight sixes, the German manufacturer has relied on one type of engine – the flat, opposed-piston twin – for longer and over a wider range of models than any other manufacturer. (The possible exception is Harley-Davidson, with its Vees, although Harley did not adopt its signature V-twin until 1909, six years after the firm’s foundation, whereas BMW motorcycles were boxer twins from the outset.)

The boxer twin layout was not actually a BMW invention. It dates back much further, to 1896, when German engineer Karl Benz pencilled a new four-stroke engine. His flat horizontally opposed twin-cylinder engine involved two pistons that reach top dead centre and bottom dead centre at the same time. The piston action was likened to two prize fighters trading blows, which is where the term ‘boxer’ engine was born. As a power unit it also had the advantages of being tightly packaged, robust and versatile.

It was not until 1920 that the newly reorganized aero engine company, BMW, became associated with the type. One of the company’s leading engineers, Martin Stolle, had a British 500cc flat twin motorcycle, with the cylinders positioned fore and aft. This intrigued BMW designer Max Friz, who then designed his own version of the unit to be used primarily for aviation and as a static generator engine. This engine, designated the M2B15, was also sold to a number of up-and-coming German motorcycle manufacturers. Despite the inherent overheating problem of the fore/aft cylinder arrangement, it was such a success that BMW began to produce its own motorcycle using the engine, marketed under the Helios brand.

It was what happened next that truly set BMW motorcycles, and what became its signature boxer engine, on the road to success.

The original ‘airhead’, an R32 at the BMW Museum in Munich.

Friz was a man of ingenuity. He soon realized that the overheating problem could be solved simply by turning the M2B15 engine through 90 degrees, so that the cylinders ran across the width of the frame. In this layout, both cylinders would be exposed to the passing air. The simple repositioning also allowed the use of a shaft final drive system, as the crankshaft now lined up with the gearbox, friction clutch and driveshaft. This proved to be a superior (direct and clean) method of delivering driving torque to the rear wheel in comparison with the usual chain and sprocket system. The crankshaft and three-speed gearbox of the revised 500cc M2B15 engine benefited further by being contained within their own cast cases, unlike the separate engine and gearbox pre-unit powerplants of many European motorcycle manufacturers.

Designated as the M2B33, the revised engine was the first true BMW boxer powerplant and would power the first Friz-designed BMW motorcycle, the 1923 R32. It was quite simply a revelation, so much so the Bavarian marque stuck with the distinctive engine layout for decades of successors. BMW did build smaller singles from time to time as a cheaper alternative to the larger, more luxurious twins. However, by the outbreak of the Second World War, and particularly as the German firm grew in the 1950s and 60s as a specialist manufacturer of luxury, large-capacity touring motorcycles, the words ‘BMW’ and ‘boxer’ became synonymous.

Of course, it took other great machines after the R32 to cement that identity – and there were plenty. There was the pre-war (1937) Kompressor, which became the first foreign winner of the Senior TT and also set a land speed record. There was the wartime R75, which was arguably the best military motorcycle of all and went on to be blatantly copied both in Russia and the USA. At the beginning of the 1950s came the 500cc R51, while the end of the decade saw the introduction of the sporty 600cc R69. The end of the 1960s was the era of the all-new /5 series, which was followed in the 70s by not just the R90S but also the revolutionary, aerodynamically faired R100RS. Then in the early 1980s came the truly ground-breaking R80G/S, the world’s first adventure bike.

All of these machines – and many more – were air-cooled, opposed-piston flat twins. As such, they were instrumental in creating the BMW boxer legend. The story of those bikes, of the creation of BMW, of its inspired designs, and of all of the different air-cooled boxers, right up to their ultimate replacement in the 1990s, is one that has it all: revolutionary designers, heroic racers, wartime conquests, adversity and triumph, innovation and glory – and, of course, brilliant BMW bikes. Loads of them. No wonder they retain such a strong and devoted following to this day.

The TT-winning supercharged BMW Kompressor.

The 1960 R69S, one of the most revered BMW boxers of all.

The iconic 1973 R90S (and rider in period gear!).

The 1980 R80G/S, the boxer that saved BMW and created the ‘adventure’ class.

FROM BARTER TO BMW – THE ORIGINS OF THE BOXER

The original idea for a horizontally opposed ‘boxer’ engine was first patented by German engineer Karl Benz in 1896 but it was a Briton, Joseph F. Barter, who first fitted it to a motorcycle. After fitting a single-cylinder motor to a bicycle in about 1902–1904 and finding it unsatisfactory, he tried a flat twin boxer instead, mounting a 200cc engine in line with the frame and quite high up. He used chain drive to a counter shaft with a clutch then connected to the rear wheel by a belt.

Barter’s Light Motors Ltd put the ‘Fairy’ into production in 1905 but the company folded in 1907, and the rights to the motorcycle and engine were sold to Douglas Engineering. Douglas modified the Fairy by increasing capacity to 350cc. In 1911, the engine was moved lower in the frame and later gained mechanically operated valves. There were two models: a 350cc producing 2¾hp and a 544cc producing 4hp.

During the First World War, Douglas provided around 70,000 motorcycles to the military and at the end of hostilities many remained in Europe. In Germany, a 500cc Douglas found its way into the hands of Martin Stolle, works foreman at BMW, and this was the model that inspired BMW’s chief engineer Max Friz. According to an alternative history, it was a British ABC design from 1919, which had a 400cc transversely mounted, chain-driven boxer twin, that had been sold to BMW. However, this has been flatly denied by the Bavarians…

CHAPTER ONE

IN THE BEGINNING: THE BIRTH OF BMW

The original BMW roundel logo. Today it is one of the world’s most recognized brands.

To appreciate fully the history and culture of BMW motorcycles and thus the origins and philosophy surrounding the company’s use of the airhead boxer twin, it is useful to have an understanding of the origins of BMW itself. At its inception, the company was about anything but bikes.

The Bayerische Motoren Werke (or, in English, Bavarian Motor Works) is now primarily known for cars such as the X5 or 3 series, with motorcycles a comparatively minor, although still important, sideline. It now includes the historic British Mini brand as well as Rolls-Royce. As recently as 2018, the company built in excess of 2,500,000 vehicles, in plants in countries as diverse as Brazil, Egypt, India, South Africa, the USA and, of course, Germany. BMW motorcycle production for the same period, meanwhile, was around 150,000 globally, with the vast majority of those built in Germany at the Spandau Factory in Berlin. (The exception is BMW’s recent, entry-level G310 single-cylinder family of machines, which are made in association with TVS in Chennai, India.)

BMW’s origins, however, at the beginning of the twentieth century, were very different, with the ‘motoren’ in the name applying more to aircraft engines than to any other type.

Although the company’s official history dates its founding to 7 March 1916, the story of BMW’s origin is less clear-cut. For example, the company did not officially adopt the BMW name until a year after its formation. To add to the confusion, the BMW name was then transferred to a different company in 1922. Essentially, however, the birth of BMW is the story of two fledgling aero companies in the ‘Wild West’ aviation days of the First World War. One specialized in planes while the other focused on engines, and the two were eventually merged to become one.

BMW motorcycles came about as a result of the post-First World War Treaty of Versailles in 1919, which forbade German aircraft production for five years. (Another, later, by-product was the formation of Messerschmitt in the 1930s from the remnants of one of the old aero firms, which later became responsible for the Bf 109 and Me 262 of the Second World War.) Looking to save the company after the ban on aircraft production, BMW began to supply proprietory engines to other motorcycle manufacturers, and made the move into producing its own motorcycles in 1923. Perhaps this history helps to explain why, today, motorcycles remain such an important part of the BMW identity. The subsequent move into car manufacture came only in 1928, after BMW purchased the Automobilwerk Eisenach car company.

BMW’s modern headquarters and museum in Munich.

The early twentieth century was an exciting, dynamic and pioneering time for the development of aviation, with daring, ambitious young men being inspired by the record-breaking feats of the Wright Brothers in 1903 and Louis Blériot in 1909. It was a fascinating period characterized by the rapid emergence (and often just as swift disappearance) of new aircraft companies. In Germany, one of the very first of these was the Aeroplanbau Otto-Alberti workshop near Munich, founded in 1910 by Gustav Otto, the son of Nikolaus Otto, who had defined the principle of the four-stroke internal combustion engine in the 1860s. Renamed Gustav Otto Flugmaschinenfabrik in 1911, this company began aircraft manufacture specializing in the ‘pusher’ propelled aircraft then used by the Royal Bavarian Flying Corps.

Flugwerk Deutschland was another of those early aviation companies, founded in 1912 to manufacture aircraft and aero engines. Although headquartered near Aachen, it also had a branch in Munich at a former bicycle factory, managed by Joseph Wirth and a young aero engine designer by the name of Karl Friedrich Rapp. As was common in those days, Flugwerk ceased operations in 1913. Rapp, along with Viennese investor, Julius Auspitzer, purchased the remnants and founded a new company, Rapp Motorenwerke, to continue engine and aircraft production at the Munich site. It was Rapp Motorenwerke that became the core business from which BMW would later emerge.

Rapp’s proximity to Otto was crucial – indeed, one of the reasons for Rapp launching his business was because he had a contract with Otto to supply four-cylinder Type II aero engines. With the onset of war in 1914 the demands for that engine, and for other types, increased, and Rapp was able to expand his business rapidly. However, this growth would also, ultimately, prove to be the cause of Rapp’s demise, in turn leading to the creation of BMW.

One of the newer engines demanded by the war ministry was the Austrian Austro-Daimler V12. In early 1916, Viennese Franz Josef Popp, who worked for the Austro-Hungarian government, was looking for a sub-contractor to help manufacture the V12. Although he was sceptical about Rapp’s own abilities in terms of design and production, he recognized that his company had good facilities and a talented workforce. Rapp Motorenwerke was awarded the contract, with the proviso that Austro-Daimler would delegate an officer to Munich to oversee quality control. That man was Popp himself.

A disciplinarian with an obsessive eye for detail, Popp quickly became increasingly involved in the running of the entire company at Rapp Motorenwerke. Rapid expansion led to a need for capital investment, which came from central government, along with state control. Karl Rapp, meanwhile, had become distracted in trying to gain recognition for his new six-cylinder engine, basically a Type II four-cylinder unit with two extra cylinders crudely grafted on. The clumsy design was not a success. The unevenly spaced cylinders and asymmetrical crank resulted in an inordinate degree of vibration, so much so that the Prussian ministry, despite its desperate need for a high-performance six-cylinder Type III engine, refused to approve it.

The original Otto-Flugzeugwerke factory.

At this point, Popp took matters into his own hands. First, he hired a young former Daimler engineer named Max Friz, who came armed with his own idea for a powerful, high-altitude aero engine – in other words, just what the Prussian war ministry were after. In the years to come, it was Friz who would become the designer of BMW’s world-beating first motorcycle, the R32 of 1923.

Second, with government officials losing patience with Rapp and his flawed six-cylinder, Popp took his opportunity to make a radical change when a team of inspectors travelled to Bavaria. Their aim was to turn the Rapp works away from producing its own engines and towards manufacturing Daimler or Benz designs under licence, along with being a repair depot. According to BMW legend, Popp used the inspectors’ lunchbreak to present Friz’s plans for a new high-altitude, six-cylinder engine. The inspecting team were so impressed that they went on to place an order for 600 units – before a single prototype had been produced. In short, the Friz engine turned Rapp Motorenwerke into an essential contributor to the war effort virtually overnight and so changed the direction of the whole company.

However, it also signalled the end for Karl Rapp. The price of the lucrative contract was the removal of Rapp from control and a re-formation of the company. In April the following year it was renamed Bayerische Motoren Werke GmbH, and the first incarnation of BMW was born.

BMW’s first product, naturally enough, was the Type III engine, which quickly became renowned for good fuel economy and, in Type IIIa form, for high-altitude performance. The resulting orders for the engine from the German military contributed to further rapid expansion. An increased requirement for capital investment and the financial difficulties that came with it also led to BMW being floated as a public limited company: BMW AG was founded on 13 August 1918, taking over all the assets, workforce and orders from BMW GmbH. The private company was wound up on 12 November 1918. The share capital of the new BMW AG amounted to 12 million reichsmarks and was bought by three groups of investors. One third of the shares was taken up in equal parts by two banks, another third was acquired by Nuremberg industrialist Fritz Neumeyer, and the final third was taken up by Viennese financier Camillo Castiglioni, who would later be instrumental in the re-direction of BMW.

The biggest difficulty for original BMW came with the end of the First World War. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, all German companies were banned from aircraft production. BMW was forced to turn to farm equipment, household items and railway brakes, and, as was the case for much of the post-war German economy, times were hard. Railway brakes were the most lucrative area of manufacture, being sub-contracted from railway company Knorr-Bemse, but BMW was still barely profitable and most of its aircraft skills, patents and facilities, remained unused. By 1920, most of BMW, including Castiglioni’s shares, had been absorbed by Knorr-Bemse.

BMW was not the only former German aero company facing troubled times. Despite initial success, Gustav Otto’s pioneering Flugmaschinenfabrik also quickly ran into difficulties, particularly after the onset of war. In 1916, financial pressures led to the company being taken over by a consortium of banks and reorganized as Bayerische Flugzeugwerke AG, or BFW, on 7 March of that year – incidentally, the same date that is considered to mark the birth of the BMW company, for reasons that will become shortly clear…

Max Friz designed the first Type III engine before moving into motorcycles.

Production of the 500th Type IIIa aero engine in 1918. This was the engine that launched BMW to success.

GUSTAV OTTO – LAYING BMW’S FOUNDATIONS IN FLIGHT

Gustav Otto was key to the creation of what would become BMW.

The son of Nikolaus Otto, the inventor of the four-stroke internal combustion engine, Gustav Otto was a leading pioneer in the German aircraft and aero engine industry in the early 1900s. He was to be integral to the formation of what would become BMW.

After first founding the Aeroplanbau Otto-Alberti workshop, Otto designed, in 1910, a biplane which created a sensation. Several companies later, in 1913, after selling 47 aircraft to the Bavarian Army, Otto opened the Otto-Flugzeugwerke factory. He chose Munich for its location, in order to be close to the German government’s military procurement process.

Despite Otto’s success, however, wartime stresses led to financial problems (and his own medical issues), which ultimately led to his forced resignation. In February 1916, his assets were taken over and reorganized to become Bayerische Flugzeugwerke, which was owned by engineering company MAN and a consortium of banks. The new company, known as BFW for short, and later the site and shell into which BMW was moved, was officially registered on 7 March 1916 – the date is recorded today by BMW’s corporate history as marking its foundation.

Following the First World War, Otto began a new move into automobile manufacture with the Starnberger Automobilwerke, but continued to suffer health and personal issues. He was divorced in 1924 and his ex-wife died in mysterious circumstances in 1925. Tragically, Otto committed suicide in 1926, at the age of just 43.

KARL FRIEDRICH RAPP – BMW’S ‘INDIRECT’ FOUNDER

Karl Rapp. BMW was formed out of Rapp Motorenwerke.

Karl Friedrich Rapp was a German aero engine designer and engineer who went on to found Rapp Motorenwerke in Munich in October 1913. This was the company that went on to be re-formed as BMW. As such, although he was ousted from the company before it was renamed, Rapp is acknowledged today as an ‘indirect’ founder of BMW.

Rapp was born in 1882 in Ehingen, but little is known of his childhood. He trained as an engineer, being employed first by the Züst automotive company from 1908, before joining Daimler in 1911. He left Daimler in 1912, to head a branch of Flugwerke Deutschland near Munich.

After the liquidation of Flugwerke in 1913, Rapp and an Austrian investor named Julius Auspitzer bought the assets and set up Rapp Motorenwerke on the same site, with the intention to build and sell aircraft and automotive engines. With a contract to build the Otto Type II engine, expansion was rapid. By1915, Rapp Motorenwerke employed 370 workers and was one of the key Bavarian companies contributing to the German war effort. However, many of Rapp’s own designs were flawed and unsuccessful.

After the securing of a contract to build the Austro-Daimler V12 for the Austrian government, Rapp was joined by Franz Josef Popp, who was tasked to supervise the order on behalf of the Austrian war ministry. Rapp’s design for a six-cylinder Type III engine had been rejected, so Popp employed designer Max Friz to come up with a new design, which was duly accepted. Rapp resigned shortly after, in spring 1916, leading to the reorganization of the company under Popp. It was renamed Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW) GmbH the following year.

After leaving the eponymously named company, Rapp became chief engineer and head of the aero engine department of the L. A. Riedlinger Machine Factory, where he was employed until October 1923. In the 1930s Rapp moved to Switzerland, where he ran a small observatory. He died in Locarno in 1962.

FRANZ-JOSEF POPP – BMW’S EARLY GUIDING FORCE

Franz Josef Popp was a crucial force behind BMW right through its early years.

Franz-Josef Popp was one of the key men responsible for the founding of BMW, and its first general director, from 1922 to 1942.

Born in Vienna in 1886, he gained a degree in engineering in 1909 and at the beginning of the First World War joined the Austro-Hungarian and Royal Aviation Troops, where he oversaw aircraft engine production, latterly at the Austro-Daimler works. Identifying insufficient production capacity for its own new 12-cylinder aircraft engine, Austro-Daimler tasked Popp with finding a suitable manufacturer. The contract was awarded to Rapp Motorenwerke in Bavaria in 1916, and Popp was despatched to Munich to oversee production. Concerned about poor standards, he began to take on the role of Rapp factory manager and, aware that Rapp required a quality designer, hired Max Friz.

Following the failure of Karl Rapp’s Type III design and the success of Max Friz’s version, it was decided that Rapp should be removed from control of his eponymous company. Popp was installed as managing director and the company was reorganized, to be renamed as Bayerische Motoren Werke GmbH in April 1917. Following BMW’s conversion into the public limited stock company BMW AG, in November 1918, Popp became chairman of the board and general director.

In the aftermath of the First World War, he attempted to diversify BMW’s products and was instrumental in assisting Camillo Castiglioni in the creation of the new BMW AG in 1922. Following this, under Popp’s management, BMW began to expand into motorcycles and motorized transport, including, from 1928, cars.

During the 1930s, BMW became Nazi Germany’s leading aircraft engine manufacturer and, in 1933, Popp himself joined the Nazi Party, although he maintained he did so purely to prevent his removal as general director. Wartime tensions and disputes led to his removal in 1942 and, despite attempting to rejoin BMW after the war, he was unsuccessful. He died in Stuttgart in 1954.

THE ORIGINS OF THE BMW ROUNDEL

Today, BMW’s blue and white roundel logo is one of the world’s most recognized and revered commercial symbols, but its origins are not generally well known.

The name Bayerische Motoren Werke was first registered in July 1917 by Franz Josef Popp, who was keen to distance the new aero engine company from the old Rapp Motorenwerke. The first trademark, however, was not registered until 5 October of that year. It was an evolution of the old Rapp logo, featuring the same circular design, but one key difference was the insertion of the letters ‘BMW’ into the top section of the outer ring. The inner section was divided into quadrants in blue and white, inspired by the colours of the Bavarian Free State, but in reverse order – it was illegal in Germany at that time to use national symbols in commercial trademarks.

Contrary to popular folklore, the logo was not in any way originally intended to represent an aircraft engine or propeller. That association comes from a 1929 advertisement, which featured aircraft with the image of the roundel in the rotating propellers. The advertisement was created following BMW’s successful acquisition of a licence to manufacture the American Pratt & Whitney radial aircraft engine. It was a significant development for BMW, which came at a time when the business world was about to enter the Great Depression.

The concept of the spinning propeller was given further exposure in an article written by Willhelm Farrenkopf, published in 1942 in a BMW journal. This also featured an image of an aircraft with a spinning roundel and the folklore was born.

In the original design of the roundel, the lettering and outline were in gold, but by the time the first BMW motorcycle, the R32, was released, in1923, it had changed slightly. The letters were still in gold but the font was bolder and the letters were closer together. This was the style that was submitted to the German Register of Trade Marks in 1933, although a variety of versions were still used. Proportions changed, the shade of blue varied and the lettering could be in gold, white or silver, with serif or sans serif fonts in different sizes, with little rhyme or reason.

By the 1950s, there was a more concerted effort to standardize the roundel, with white lettering that became silver when used on cars and motorcycles. In the 1960s the serif font was replaced by sans serif, and this was being used on all motorcycles by 1966. A slightly bolder font was adopted subsequently and this has remained as the standard.

The company briefly flirted with an additional variant in the early 1970s and 80s, conceived to identify its high-performance ‘M’ cars. This comprised the standard BMW roundel but with the BMW Motorsport ‘rainbow’ colours surrounding it. In 1997, BMW moved to depicting the roundel in 3D when used in the printed form, giving it a bolder look. Today the BMW roundel is ranked in the top ten of the world’s most recognized commercial logos and is an iconic symbol in its own right.

The new BMW logo was based on that of Rapp Motorenwerke, with the addition of the colours of Bavaria.

Over the years, the BMW roundel has continually evolved.

FIRST SOARING SUCCESS – THE BMW TYPE III, IIIA AND IV AERO ENGINES

The first product of the newly formed Bayerischen Motoren Werke, or BMW, in 1917, was the Type III engine designed by Max Friz, which had also been dubbed ‘BBE’. It was water-cooled, and laid out in an in-line six-cylinder configuration, which guaranteed optimum balance and therefore little vibration. Registered on 20 May 1917, it was quickly a success, but an even bigger breakthrough came later that year when Friz integrated a simple throttle butterfly into the ‘high-altitude carburettor’, which enabled the engine to develop its full power high above the ground. This was the reason why the engine, now known as the Type IIIa, gained unique superiority in air combat.

In 1918, the engine was used to power a BFW biplane to an altitude of 5,000 metres in just 29 minutes. It was an impressive feat that led to strong demand for BMW engines from the German military, in turn leading to the rapid expansion of BMW. Later, a Type IIIa was also used to power a Junkers F.13 passenger aircraft, which, with eight people on board, reached an altitude of 6750 metres, a record for a passenger aircraft. The following year, on 17 June 1919 – just before the terms of the Treaty of Versailles prohibited the German manufacture of aircraft engines – a successor to the Type IIIa, the Type IV, was used to set a new world altitude record. The plane was a DFW-F37/III, piloted by BMW test pilot Franz-Zeno Diemer, and took 89 minutes to reach 9760 metres (32,013ft). It was BMW’s first official world record.

The setting of a world altitude record in 1918 fuelled BMW’s first successes.

Franz-Zeno Diemer before setting his world altitude record in 1919.

CHAPTER TWO

1920–1930: THE MOVE INTO MOTORCYCLES

At the start of the 1920s, BMW was in virtual disarray. Banned from aero engine manufacture, its facilities were under-utilized and it was barely solvent. It was also, technically, not even the same company it would soon become following a takeover, merger and renaming. That came in 1922 and led directly to BMW’s emergence as a motorcycle manufacturer, with the pioneering, radical – and, crucially, boxer-twin-powered – Max Friz-designed R32 in 1923. Before then, however, a number of crucial developments took place.

THE ‘BAYERN ENGINE’

The signing of the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919 was an event that not only fundamentally re-shaped Europe, and particularly Germany, but also indirectly created a new future for BMW. Banned from manufacturing military aircraft and engines, the company whose only First World War product was the Type IIIa aero engine was suddenly forced to find alternative work. At first, BMW tried to sell cut-down aero engines to the marine and industrial sector, but there were not enough orders to keep the company going. In the end, BMW owed its survival to Knorr-Bremse, a railway brake manufacturing firm that was looking for contracts in Bavaria.

Although it was now profitable, BMW’s aero engine patents, aluminium foundry and other aero facilities remained idle – so much so that, in 1920, major shareholder Camillo Castiglioni decided to sell his BMW shares to the chairman of Knorr-Bremse. Still seeking alternative work for its facilities, BMW general director Popp asked works foreman Martin Stolle to come up with a small proprietory engine for use as a generator. Stolle had a British Douglas motorcycle powered by a longitudinal boxer twin engine. Engineer Max Friz suggested ‘reverse-engineering’ the engine and the result was the M2B15, a portable, 494cc air-cooled boxer twin that produced 8.5bhp at 3,400rpm. It quickly came to the attention of some of Germany’s fledgling motorcycle manufacturers and soon became known as the ‘Bayern engine’.

Heller, Biso, Corona and Victoria are some of the earliest recorded motorcycle manufacturers who used the Bayern engine to power their motorcycles. However, while it proved reliable as a generator, installing it in a motorcycle chassis, with the two cylinders running in-line with the length of the frame, tended to restrict the cooling effect of the air passing over the rear cylinder. Despite some overheating problems, the engine was such a success that BMW eventually decided to use it to produce its own motorcycle. The first BMW-powered motorcycle was born under the manufacturing name of Helios, a brand inherited in the company merger. (Around the same time, incidentally, BMW also developed and manufactured a small motorized bicycle powered by a Kurier two-stroke engine and called ‘Flink’. This proved unsuccessful.)

THE BIRTH OF BMW

Towards the end of 1921, financier Camillo Castiglioni, who had earlier sold his shares in BMW AG, became significant in the story again. With engine specialists BMW becoming more and more subsumed into Knorr-Bremse, and Helios owner Bayerische Flugzeugwerke similarly struggling on, Castiglioni made a bid for BFW. By early 1922, with the assistance of BMW’s Franz Popp, he had convinced owners MAN to sell up. Then, with the Munich manufacturing facility of BFW’s former Otto works in his pocket, the Helios motorcycle that came with it and the ban on aero engines about to be lifted, Castiglioni did another audacious deal: on 20 May 1922, he bought the BMW name, logo and enginebuilding business (but not its premises) from Knorr-Bremse for 75 million reichsmarks.

With the deal done, Bayerische Flugzeugwerke was merged with BMW and the factory and headquarters were established at the old BFW premises. The new concern was renamed BMW and retained BFW’s incorporation date of 7 March 1916. In short, the current BMW was born. To this day, the original establishment of BFW is recorded in the company’s official history as the birth date of BMW. BMW’s headquarters have been at the same address ever since.

Financier Camillo Castiglioni played a key part in BMW’s re-organization.

THE FIRST BMW BOXER – THE M2B15

In 1921, Max Friz asked to borrow a British Douglas motorcycle owned by one of his foreman, Martin Stolle. His idea was to ‘reverse-engineer’ a new BMW light industrial engine from the bike. The resultant motor was the M2B15, a side-valve 494cc air-cooled longitudinal boxer twin that produced 8½hp at 3,400rpm. Adopted for a number of German motorcycles, including Victoria and the Helios, it became the inspiration for BMW’s first complete motorcycle, the 1923 R32.

When Camillo Castiglioni bought the premises and manufacturing machinery of BFW, negotiated a separate deal for the engineering know-how and BMW brand and merged them together under the BMW name, one of the by-products was the formerly BFW-owned Helios motorcycle division, which used the BMW-built M2B15 engine. It was almost inevitable that a BMW-built and -branded motorcycle would follow.

BMW’s proprietory M2B15 engine paved the way for the company’s move into motorcycles.

German motorcycle manufacturer Victoria was among the first to use the BMW engine.

Helios also used the BMW engine; it was subsequently absorbed by the Bavarian company as part of its reorganization.