33,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

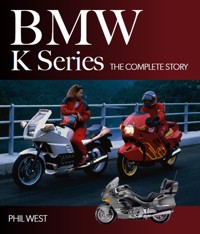

While BMW motorcycles remain mostly associated with its R-series shaft-drive boxer twins, it's the K-series liquid-cooled 'multis' that have been – and remain – the German firm's most advanced, radical and downright wacky bikes of all. Launched in 1983 to propel BMW into a whole new era, the K-series has included some of the world's most innovative and interesting motorcycles. From the original liquid-cooled, fuel-injected K100, to the radically aerodynamic K1 of the 1980s; the ultra-powerful K1200RS and space age K1200LT of the 1990s; and the 'Duolever' K1200S and 6-cylinder K1600 of the 2000s and beyond, BMW's 'Ks' have always been special, but also so advanced and pioneering that they've helped shape the whole of modern motorcycling. BMW expert Phil West, author of BMW Airhead Twins and BMW GS, also published by Crowood, has again painstakingly researched their complete history, found pictures never published before and recounts the whole K-Series story in a comprehensive and engaging tale.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 283

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

OTHER TITLES IN THE CROWOOD MOTOCLASSICS SERIES

AJS and Matchless Post-War Singles and Twins Matthew Vale

BMW Airhead Twins Phil West

BMW GS Phil West

Classic TT Racers Greg Pullen

Ducati Desmodue Greg Pullen

Francis-Barnett Arthur Gent

Greeves Colin Sparrow

Hinckley Triumphs David Clarke

Honda V4 Greg Pullen

Moto Guzzi Greg Pullen

Norton Commando Matthew Vale

Royal Enfield Mick Walker

Royal Enfield Bullet Greg Pullen

Rudge Whitworth Bryan Reynolds

Triumph 650 and 750 Twins Matthew Vale

Triumph Pre-Unit Twins Matthew Vale

Triumph Trident and BSA Rocket 3 Peter Henshaw

Velocette Production Motorcycles Mick Walker

Velocette – The Racing Story Mick Walker

Vincent David Wright

Yamaha Factory and Production Road-Racing Two Strokes Colin MacKeller

First published in 2022 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2022

© Phil West 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4111 8

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank a few individuals for their help and support in producing this book. The late, great Mick Walker, whose original 1989 book BMW K-series Motorcycles so successfully and comprehensively told the early years of BMW’s K – how amazed he would surely be by the six-cylinder wonders the machines have evolved into today. Neil Allen at BMW Motorrad UK for his kind assistance in allowing the use of pictures for this book. My wife, Sarah, yet again for her support, tolerance and occasional lunch while I toil away at the keyboard; my late dad for encouraging and facilitating my first forays into publishing and journalism; my late mum whose grasp of English was always better than mine; my two kids, Cleo and Olly, for being my inspiration and, finally, all at Crowood for having the confidence to help me make this book happen.

CONTENTS

Preface

CHAPTER 1 BMW MOTORCYCLES BEFORE THE K SERIES (1923–1983)

CHAPTER 2 A NEW HOPE (1975–1983)

CHAPTER 3 THE NEW TOURING STANDARD (1984–1991)

CHAPTER 4 AND THEN THERE WERE THREES… (1985–1996)

CHAPTER 5 THE POWER AND THE GLORY (1988–1993)

CHAPTER 6 K TOURERS ENTER THE ‘BIG’ TIME (1992–1999)

CHAPTER 7 K1100 RS – THE EXECUTIVE EXPRESS (1993–1996)

CHAPTER 8 THE NEXT GENERATION (1997–2004)

CHAPTER 9 REINVENTING THE ‘FULL-DRESSER’ (1999–2009)

CHAPTER 10 THE ‘GRAND TOUR’ (2003–2005)

CHAPTER 11 TURNING THE K AROUND (2004–2008)

CHAPTER 12 SPECIAL KS (2005–2008)

CHAPTER 13 BIGGER, BETTER… (2009–2016)

CHAPTER 14 EXPLORING 6 CYLINDERS (2009)

CHAPTER 15 THE JOY OF SIX… (2011–2017)

CHAPTER 16 NEW HORIZONS… (2017–CURRENT)

Index

PREFACE

While BMW motorcycles are rightly synonymous with the ‘R-series’ boxer twins that are at the core of its history and heritage, it is the German firm’s alternative K series – its high-tech, multi-cylinder motorcycles – that are just as significant in its recent history.

First launched in 1983 with the ultra-modern K100, a liquid-cooled and fuel-injected four-cylinder that was radically laid ‘flat’, BMW’s ‘new direction’ quickly spawned a whole family of high-tech K-series machines. These remain, in the form of the current six-cylinder, luxurious K1600GTL, BMW’s flagship machines.

During that time over 30 different models – ranging from the K75 triple through the revolutionary K1, multiple K1100, 1200 and 1300 four-cylinder roadsters, sports tourers and tourers, in two completely different engine layouts, right up to the world-leading K1600 six – have all been technical trend-setters, featuring class-leading performance. They have also been lavished with a standard of overall luxury that few motorcycle manufacturers can match.

With this book I’ve tried to round-up all of those machines, from their radical beginnings and the men behind them in the 1980s to today’s ultra high-tech and luxurious ‘full-dressers’. I explain how they came about, what made them different and how they were received by the press and public, hopefully woven into a comprehensive and engaging tale.

Phil West

CHAPTER ONE

BMW MOTORCYCLES BEFORE THE K SERIES (1923–1983)

Today, BMW is one of the world’s biggest automotive brands. However, it is still not best known for its motorbikes – and certainly not for the relatively modern K series, which debuted in 1983.

Instead, the German firm’s origins were in the aviation industry around the time of World War I, before moving into bikes in the early 1920s and cars towards the end of that decade.

The first BMW bikes were powered by air-cooled, flat, twin-cylinder ‘boxer’ engines with shaft drive. This was an engine layout so successful that it quickly became – and remains to this day – synonymous with the brand. It was the success and dominance – but ultimately, the perceived limitations of that engine layout – which were the catalyst for the later K series.

It is only by revisiting that background – conveying the historical significance of those early bikes to BMW and the evolution and ultimate exhaustion of the air-cooled boxer layout – that the need for the K series, and the direction those bikes took, can be fully understood.

The Bayerische Motoren Werke’s (Bayern Motor Works) origins are complex and there is neither the space nor the need to chronicle them fully here. Nevertheless, a brief overview helps us to understand the origins of the K series.

BMW (Bayerische Motoren Werke) was formally created as a public company in 2018. However, its official founding is generally recognized as that of the preceding company, BFW, in 1916.

The first, privately owned BMW GmbH was founded in Munich on 29 July 1917 at the height of World War I. It was created from the pooling of Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (BFW), an aero engine company headed by Karl Rapp and aero engine designer Dr Ing Max Friz (of whom we will hear more later), with aeroplane constructor Gustav Otto.

This company then went public in August of the following year to become BMW AG, with grand designs for new aircraft and aero engines and a workforce of over three thousand… just as the war came to an end. The Treaty of Versailles that followed forbade German aircraft production, which in turn forced BMW – then under the directorship of Austrian Franz Joseph Popp – to diversify.

BMW products as varied as agricultural machinery and even office furniture followed, with only limited success, until a contract for railway braking systems helped keep the company alive. Then, gradually, BMW began to explore motorcycles.

The first BMW-made bike, which appeared in 1920, was not a success and, conveniently for the sake of history, also not a four-stroke boxer twin or even badged BMW. Instead, it was called the Flink and was powered by a single-cylinder two-stroke motor supplied by a company named Kurier. These were the early days of motorcycles, after all, when a myriad fledgling motorcycle companies across Europe and the USA began experimenting with bikes powered by proprietary engines made by separate suppliers.

A degree of success, however, soon followed. The year 1921 saw Friz himself design a new proprietary engine. This was called the M2B15 and, significantly, was a 493cc flat twin. This was then sold by BMW to German motorcycle manufacturers such as SMW and Victoria. With chain drive, the engine was mounted longitudinally – not transversely as later BMWs would be – and was also used in the Helios, a machine built, but not designed by, BMW.

Despite his historical legacy as the ‘father of BMW motorcycles’, Friz himself was not a fan of bikes – and certainly not the Helios. He viewed it as badly designed, not worthy of his engine and a machine that threatened his good reputation. In short, he knew he could design a better motorcycle himself and, unable to design the aero engines he loved, set about to do just that.

The result, the R32, was BMW’s first complete motorcycle and was unveiled at the Paris Show of 1923, where it caused a sensation.

Beginning with aero engines, then planes, the end of the First World War forced BMW to turn elsewhere – launching its first motorcycle, the R32, in 1923.

What made the R32 stand out were a number of pioneering design features. First, Friz revisited his flat-twin engine design and, with one eye on improved cooling and another on shaft drive, reconfigured it to be mounted transversely, with the cylinders poking out sideways into the airflow and with a novel shaft drive. It also featured a pioneering, four-speed, manual gearbox complete with a car-style clutch, an advanced trailing link front fork with twin leaf springs suspension above the mudguard. Additionally, the R32 was a fully integrated design with stylish, art deco-inspired styling. Though not cheap, nor as powerful as some others, the R32 was an instant hit with over 3,000 sold over the next three years. BMW Motorrad was on its way.

The success of the R32 led, inevitably, to a series of successors. These were not developed by Friz – who by this time had returned to his beloved aero-engine design – but rather by Rudolph Schleicher, with many of his designs proving pioneers in their own right.

Schleicher’s 1924 R37 – again based on a boxer-style twin-cylinder engine – was the first motorcycle to feature light alloy cylinder heads, while the larger 750cc R12 and R17 of 1934 pioneered hydraulically damped telescopic front forks.

These successes, accompanied by a series of publicity-generating motorcycle world speed records achieved by Ernst Henne aboard specially prepared, supercharged machines, helped BMW to weather the depression of the early 1930s. This forced many German motorcycle rivals to the wall and ultimately propelled Adolf Hitler into power, whereas BMW grew strongly and became established as one of Germany’s leading automotive brands.

After first building British Austins under licence, BMW’s own first car came in 1932. Meanwhile, a series of more affordable, single-cylinder bikes cemented its success as a motorcycle manufacturer, even though its bigger, more prestigious boxer twins remained its ‘bread and butter’. As a result, by 1935 the total number of BMW’s employees had risen to 11,113.

Further advances to the boxer design came with the R5 in 1936. Around the same time, BMW’s racing activities, encouraged under the Nazi regime, reached unforeseen heights by dominating the Isle of Man TT in 1939 using a radical, magnesium, supercharged boxer-powered works racer – the famed ‘Kompressor’. Production numbers for BMW motorcycles also reached new heights during this period, easing past the 100,000 mark just before the outbreak of the Second World War.

Success soon followed with a sporting highlight being its domination of the 1939 Senior TT with Georg Meier on the supercharged ‘Kompressor’.

World War II, of course, changed everything, with production turned over to aero engines and the R75 (another boxer) military motorcycle. The end of the war saw BMW’s infrastructure completely devastated and its eastern plant in Eisenach taken over by the Soviets.

However, dogged determination saw BMW rise from the ashes: first by ‘reverse-engineering’ its pre-war R23 single and gaining permission from the Americans to build initially just 100 bikes; then updating it in 1948 with a four-speed gearbox to become the R24, before finally restarting boxer twin production with the R51/2.

Nevertheless, although motorcycle sales in the early 1950s were good, by decade’s end the emergence of cheap cars such as the Austin Mini and Fiat 500 devastated the German motorcycle industry and pushed BMW itself to the brink of bankruptcy. From 1961, following a takeover by the Quandt family and the subsequent launch of an all-new, affordable car – the 1500 – BMW’s car business took priority over bikes.

This move, though necessary for the survival of BMW, also sowed the seed for the ultimate emergence in the early 1980s of the all-new K-series motorcycle. Although BMW’s big touring boxer twins retained a loyal following throughout the 1960s, buoyed by the introduction of the luxurious, sporty R50 S and R69 S, BMW’s bikes were also becoming increasingly overshadowed by both the company’s own cars and by an increasing influx of more affordable Japanese motorcycles. As a result, with the company also no longer producing its cheaper singles, its boxer bikes increasingly appeared to be niche, luxury products for the few.

By the 1950s BMW was Germany’s biggest motorcycle manufacturer, famed for its ‘boxer twins’, which also proved highly successful in sidecar racing.

The luxurious, sophisticated R69 S of 1960 cemented BMW’s reputation in the 1960s as a maker of highend, exclusive, touring machines.

BMW did fight back. An all-new range of boxer twins, the /5 series, as overseen by Hans-Gunther von der Marwitz, was developed in the late 1960s and were produced in a revamped, dedicated motorcycle factory in Spandau, Berlin, with Munich now devoted to cars. These bikes had new forged cranks, plain big-end bushes in place of the old roller bearings with light alloy cylinders featuring cast-iron liners and matching alloy cylinder heads. The /5 series also had new, lighter frames with telescopic forks, new bodywork and came in 500cc, 600cc and 750cc forms to be called the R50/5, R60/5 and R75/5 respectively.

This new /5 series performed and handled better than previous models. In addition, for a while – benefiting from a new era of larger capacity ‘superbikes’, as pioneered by Honda’s 1969 CB750/4 – they sold better, too.

Nor did BMW Motorrad rest on its laurels. A further updated /6 series was unveiled at the Paris Show in October 1973 with a range of even bigger, faster boxer ‘superbikes’, headlined by the new R90/6 and R90S, the latter complete with a pioneering headlamp fairing by stylist Hans Muth. These bikes, also boasting twin front disc brakes, adjustable suspension and five-speed gearboxes, were true early 1970s ‘dream machines’ which, although not quite matching the sheer performance of the latest Japanese superbikes such as Kawasaki’s 1972 Z1 900, certainly had the style and prestige to compete.

1973’s Hans Muth-styled R90 S was a true ‘poster’ bike highlighted by its ‘bikini’ fairing, improved performance and bold two-tone paint schemes.

Although the R90 S was 120mph (193km/h) fast and a fine handler, a new breed of more affordable Japanese four-cylinder superbikes threatened its crown.

However, it was becoming increasingly clear that BMW’s venerable boxer twin was beginning to fall behind the very best multi-cylinder machines from the Far East. Although the R90S was BMW’s most powerful boxer yet – with 67bhp, enough to also make it BMW’s fastest yet, capable of 124mph – those figures were conspicuously short of the 82bhp and 132mph respectively of Kawasaki’s new Z1.

In an attempt to redress that balance BMW Motorrad made one last roll of the dice. At the Cologne Show in the autumn of 1976 the German firm made its last major effort to keep its boxer engine within reach of the new Japanese fours. To create a new flagship of its new /7 Series boxer range, BMW enlarged the bores of the engine once again – this time to 980cc – and at the same time gave it a higher compression ratio and larger exhaust, the result being a best-yet output of 70bhp @ 7,000rpm.

Even more significant was how the new bike looked. Knowing its twin-cylinder boxers could never beat the Japanese fours on horsepower alone, BMW gave its newcomer a boost by way of aerodynamics. After hiring the Italian firm Pininfarina’s wind tunnel at considerable expense, the new bike became the world’s first fully faired production motorcycle. The R100 RS was not only radical-looking, it was 126mph fast, luxurious and one of the most desirable bikes of its day. Even television’s The Saint, played by Roger Moore, had one.

The 1976 R100 RS, with a further enlarged engine and even more radical aerodynamics, was BMW’s fastest boxer yet…

…but it was also expensive and, with just 70bhp, underpowered compared to the latest ‘fours’. It was clear something had to change.

Ably supported by the new R60/7, R75/7 and R100/7, the R100 RS was the ‘ultimate’ BMW boxer and, initially at least, a significant success. But even before sales began to drop off after 1978, it was also clear that BMW’s venerable aircooled boxer had reached the practical limit of its development. At the same time, its appeal – now in a superbike world dominated not just by Kawasaki’s big ‘Zed’ and Honda’s CB four, but also Suzuki’s new GS fours and Yamaha’s XS triple – was no longer what it once was, particularly among younger buyers.

A big change was needed – and as fast as possible. The big question, however, was with what?

CHAPTER TWO

A NEW HOPE (1975–1983)

The story behind the creation of the original K-series machines, the 1983 K100 and K100 RS

The powers at BMW Motorrad in Berlin had known since the mid-1970s that a modern successor to its venerable, air-cooled boxer would soon be necessary. The emergence of ever more powerful Japanese transverse fours on the one hand combined with the global fuel crisis and tightening emissions regulations – particularly in the important American market – on the other, had led company bosses to conclude that the writing was on the wall for the large, air-cooled, boxer twin. It became obvious that a modern, liquid-cooled, ‘clean burning’ and more powerful ‘multi’ with smaller cylinders was inevitable. The unanswered question, though, was exactly what configuration this new engine would have – and when it would be launched.

When the first all-new K-series bikes – the K100 RS and K100 – were unveiled at the end of 1983, the world had never seen anything like it. But it took BMW a long time to get there….

Although BMW Motorrad is a company with a long history of innovation, up to the mid-1970s it was also a very conservative one that stuck rigidly to its distinctive, ‘signature’ boxer twins. Whatever replaced them would also have to be distinctive and adhere to a BMW ethos that emphasized touring ability and included shaft drive. By the mid-1970s, with transversely mounted, four-cylinder machines already commonplace – to the extent that they had become referred to as the ‘Universal Japanese Motorcycle’ – triples already covered by Laverda and Triumph, V-twins, whether longitudinal or transverse, the hallmark of Ducati, Harley-Davidson and Moto Guzzi respectively, few ‘distinctive’ engine layouts remained available.

On top of that, BMW Motorrad’s management at the time remained rigidly loyal to the boxer and predicted, mistakenly, that the fuel crisis would see off the escalating horse-power race so enabling its out-dated boxers to soldier on. Design projects were commissioned, but only somewhat half-heartedly. BMW motorcycle sales, meanwhile, continued to plummet.

Against this background, BMW design engineer Josef Fritzenwenger, who was working out of Motorrad’s development department in Spandau, Berlin, was quietly trying to find a viable alternative to the boxer twins.

The key ‘architect’ behind the new machines was BMW design engineer Josef Fritzenwenger.

One logical layout was simply to ‘grow’ and evolve BMW’s traditional air-cooled flat twin into a liquid-cooled flat four; this was a format that would have maintained BMW’s flat, shaft-drive, boxer tradition but developed it for the modern age. Unfortunately, Honda’s identically configured GL1000 Gold Wing of 1975 got there first and BMW had no intentions of ‘following’ the Japanese.

Then, Fritzenwenger began carrying out experiments using a water-cooled, four-cylinder, in-line engine from a Peugeot 104 car and the catalyst for a new direction was found.

Exploring potential new engine layouts, Fritzenwenger had begun experiments using a four-cylinder, liquid-cooled Peugeot car engine.

Chosen for its 1000cc capacity and light weight, the all-aluminium Peugeot motor was actually designed to be mounted transversely (across) the front of the car and inclined at an angle to minimize its height for automotive packaging reasons. Fritzenwenger, however, discovered that if he inclined the cylinder block further still, so that it was effectively ‘flat’, then rotated the whole unit 90 degrees so that the crankshaft was in line with the frame, it resulted in an engine layout that was both unique in motorcycling yet suited BMW’s requirements perfectly. In being liquid-cooled and aluminium, it was both compact and light. By being ‘flat’ it honoured BMW’s flat-twin heritage. By being a 1000cc ‘four’ it had the potential for the ‘clean’, 100bhp performance required and, by having its crankshaft longitudinally arranged, it had the potential to maintain BMW’s traditional shaft drive, something that came to fruition when Fritzenwenger later perfected ‘CDS’, or ‘Compact Drive System’.

BMW management was reportedly thrilled by Fritzenwenger’s concept, particularly as it was even more unusual and distinctive than its traditional boxer twin (which historically did actually have some similar rivals). In early 1977, they duly gave him the go-ahead to start developing it. Even so, there was a long, long way to go.

From the outset, the plan had been to produce this new engine in a variety of capacities. Initially displacements of 1300cc and 1000cc were considered, but engineers quickly found this would have resulted in engines that were both too heavy and too long. Worse, the smaller 1000cc four-cylinder engine would have been just as expensive to produce as the larger 1300cc version.

The solution was to reduce the four-cylinder engine by one cylinder to create both a smaller-capacity triple and a larger-capacity four. In the initial stages, exact displacements were not settled upon. Instead, Fritzenwenger’s team worked towards an 800–1000cc three, code-named ‘K3’, and a 1000–1300cc four, designated ‘K4’. Both were also closely based upon BMW’s existing four-cylinder car division engines, as then used, for example, in the new 1600cc, four-cylinder 316, introduced in 1975.

Even then, however, progress by Fritzenwenger’s small team was proving troublesome: positioning the exhaust and drive shaft satisfactorily proved difficult, there were valve problems at high rpm, and after 18 months development had been painfully slow.

That all changed in early 1979. Frustrated by the lack of progress and fuelled by the plummeting sales of its existing boxer models, BMW group boss Eberhard von Kuenheim installed all-new management at the top of BMW Motorrad. This would now be headed by Dr Eberhard C Sarfert and Karl-Heinz Gerlinger. It was to prove a pivotal moment.

The new programme did not start in earnest until it was given the green light by new BMW Motorrad boss Karl-Heinz Gerlinger, here pictured aboard the final production version, in early 1979.

‘When he asked us to take over this business he said: “Decide whether you make it or you close it”,’ recalled Gerlinger more than three decades later, adding: ‘But when you’re young how can you think of closing BMW Motorrad? I couldn’t do it.’

Instead, determined to give BMW’s historic two-wheeled arm its best chance of survival, Gerlinger decided to back the K-series project to the hilt. In so doing, he would ‘buy’ a little time by also giving the green light to a new R80G/S model conceived as a quickly developed bike that might appeal to the vast US market and so provide much-needed sales. (The G/S had been suggested by a group of enduromad BMW engineers and was effectively a ‘parts-bin special’ largely made out of existing components. This meant it could go into production far more quickly and would also likely appeal to the burgeoning US fashion for off-roaders and touring. Little did they then know how big it would ultimately become.)

With the K series ‘green-lighted’ and the company desperate to bring it to market as fast as practicable, BMW management then shook up the new bike’s development. Fritzenwenger’s small research and development team was suddenly expanded to 240 personnel, with Stefan Pachernegg put in overall control to allow Fritzenwenger to focus on his role as design engineer. Gunther Schier became head of running gear development; Martin Probst was head of engine development; Richard Heydenreich was head of vehicle development and Klaus-Volker Gevert became head of the design department.

However, although the team was expanded with an impressive youthful zeal (Pachernegg was just 35, Fritzenwenger 36 and, of the rest, only Heydenreich was over 50), a tough task lay ahead. Management prescribed that the new K-series bikes would not only have an individual life expectancy exceeding that of the previous boxer twins (no small ask when many of BMW’s twins lived well into their 30s and 40s), but would also be so well designed that they would still be technically acceptable in 20 years time.

On top of that they had to be fast – but also flexible and handle well – have a comfortable plush ride, be ultra-modern yet also versatile, sophisticated yet simple; in short, to be virtually all things to all people while at the same time adhering to the traditional BMW ethos.

Even so, the new team had been well chosen and attacked their task intensively. Engine chief Probst, for example, had previously been responsible for making BMW’s four-cylinder car engine the most successful Formula 2 racing engine of all time. He quickly reconfigured the layout of the prototype K-series motor so that its cylinder head was on the left instead of on the right, as was the case with initial prototypes and which had caused problems for exhaust routing.

By laying the in-line four-cylinder block ‘flat’ and positioning it longitudinally, a unique engine layout was created that had both a low centre of gravity and was suitable for shaft drive – both key BMW characteristics.

The new concept could then also deploy a fairly light, tubular steel frame, using the new engine as a stressed member.

It was also quickly decided that the larger four-cylinder version would have a capacity of 987cc with a peak power figure of 90bhp targeted. The triple, meanwhile, would have a capacity of 740cc and produce 75bhp. With the two basic formats agreed, work on the new bikes began in earnest at Spandau in May 1979.

The four-cylinder project – code-named K589 – took priority, as it had already been decided that it would be launched first, in four years time towards the end of 1983. Even so, this still enabled some basic information to be gathered for the three-cylinder version, code-named K569, as there would be plenty of shared parts and ideas.

One of the primary goals of the development team was to keep weight as low as possible. They were fully aware that, otherwise, this liquid-cooled, four-cylinder, shaft-drive machine might be prohibitively heavy. For this reason its aluminium cylinders did not employ heavy cast-iron liners, as was then common practice with alloy engine blocks, but instead had its cylinders coated with a nickel-silicon carbide abrasion-proof coating called Scanimet. This reduced friction, improved heat dissipation and allowed tighter tolerances for quieter running and better lubrication.

Weight saving was also one of the reasons that a four-valve-per-cylinder design, although initially considered, was rejected (the others being cost and ease of maintenance), in favour of a more basic two-valve layout.

Finally, with the target of a fairly modest 90bhp at 8,000rpm considered easily attainable by the K’s 987cc four (Kawasaki’s smaller 908cc four-cylinder GPz900R of 1984, by comparison, already produced 115bhp, a full 25bhp more), a fairly long-stroke 70 × 67mm bore and stroke was chosen. This was not only to keep the engine block short, as some had speculated, but also to maximize flexible, easy-riding, mid-range torque of the type suitable for touring-orientated machines. The first prototype engine was then constructed in a fairly rudimentary way with a temporary exhaust, manually adjustable timing and a crude fuel-injection system derived from that of BMW’s cars. On 18 August 1980 the new engine started for the first time.

This cross-section shows the oil filter and sump at the bottom and air intakes at the top of the layout.

With comparatively small bores and two valves per cylinder, the resulting engine was acceptably compact and light…

…yet with its ‘flat’ arrangement and distinctive, exposed looks, it also continued at least some of the traditions of the old BMW boxer.

The characteristic BMW shaft-drive system, meanwhile, was a development of the single-sided ‘Monolever’ introduced on the 1980 R80 G/S.

Early testing proved the engine a success – although there was still much work to do on the exhaust and elsewhere!

This early test mule’s 4:2 system not only looked crude but limited ground clearance significantly.

With the basics settled, the development team could then turn to honing the engine and fine-tuning its cooling and lubrication systems.

The former was taken care of by a fairly conventional aluminium cross-flow radiator, which was then made more elaborate by the decision to mimic the shape of a BMW car grille and was assisted by an electric fan behind when temperatures reached 103 degrees.

Various cam profiles were tested and the exhaust was further developed, while the pièce de résistance was the K’s fuel injection system, which was entrusted to partner Bosch and was the LE-Jetronic system. This was one of the first ever fitted to a production motorcycle, which was actually a development of similar systems already used in BMW cars.

Located underneath the bike’s seat, the ‘LE 2’ computer controlled the quality and duration of the injection, a fuel pump in the base of the bike’s 22ltr fuel tank fed the injectors and four butterfly valves fed each cylinder. First tests were encouraging and the target power of 90bhp was achieved.

With the basic configuration settled, endurance testing and fine-tuning then began. A severe, 10,000-hour bench test proved the engine’s basic construction was strong. However, the rubber ‘bumpers’ on the output shaft proved a problem at first, as the material deteriorated from the heat of the engine oil, which forced a prolonged investigation before eventual improvement. Once this problem was solved, the K589 prototype was ready for road testing.

In the autumn of 1981 the first two complete prototype machines, still using modified exhausts from BMW’s boxer twins and wearing heavy camouflage and a temporary injection system, covered 60,000km (27,282 miles) each. The following spring, adjusted according to the outcome of those first tests, a further three new prototypes were taken to the motor industry test track at Nardo in southern Italy. There the bikes were run virtually round the clock around its 12-km (7.5-mile) circular track, each covering another 30,000km (18,641 miles). Still suffering minor oil-seal and fuel-injection problems, the development team returned to Nardo in the autumn of 1982 with further updated prototypes.

At the same time, the rest of the new K-series bike was being developed and fine-tuned. The car ‘theme’ was continued with the alternator, which was again adapted from one used on BMW cars. A five-speed gearbox was chosen as being all that was necessary given the torque and flexibility of the engine. Meanwhile, the shaft drive was a development of the single-sided ‘Monolever’ already developed by BMW Motorrad for its boxer-powered 1980 R80G/S. A drive shaft ran from the gearbox on the bike’s right-hand side to the crown wheel and pinion housing through a chunky, L-shaped, one-sided alloy arm – the single-sided aspect being chosen to save weight and, as particularly useful on the G/S, aid wheel removal.

The nature of this ‘self-contained’ powertrain, which also supported the rear wheel, helped make the K’s frame simple and lightweight, as well. With little more to do than to connect the top of the rear suspension with the steering head and be a locating point for the bodywork and radiator, the K’s frame could be a simple, tubular steel trellis that weighed only 11.3kg (25lb).

The telescopic front forks were fairly simple and conventional, too. By the late 1970s BMW had discarded the ‘Earles type’ forks it had used extensively in the 1950s and ’60s when BMWs were often the bikes of choice for sidecar use (indeed BMW’s greatest racing successes of that era were in Grand Prix sidecar racing). The firm’s bikes were now, almost exclusively, used as ‘solos’, for which telescopics were superior. Those used in the new K series were very similar to those in its 1970s boxers and again, with one eye on keeping weight to a minimum and another seeing no advantage in home suspension adjustment, they had no provision for adjusting either spring or damping rates.

At the rear, again like the R80G/S, a single, side-mounted monoshock was used, although this time with a three-way preload adjuster to compensate for carrying luggage and/or pillion.

The K’s brakes, too, were conventional for BMWs of the era. Although celebrated today for their premium, sporting excellence, back in the 1970s and ’80s, Italian company Brembo were established as BMW’s brakes supplier. The K’s twin 285mm stainless-steel discs at the front (with an identical item at the rear), all grasped by Brembo’s then standard single-piston caliper, were normal BMW fare.

The K’s wheels were fairly standard items as well. 18-inch designs were at the time the norm (17-inchers only became motorcycling’s benchmark in the late 1980s) and BMW had been among the first of the major motorcycle manufacturers to standardize the use of cast-aluminium designs with its R100RS in 1976. However, a 17-inch rear wheel was settled on for the K to give a slightly more accessible seat height.

The angular styling was influenced by BMW cars of the era, such as the M1, and conceived to provide protection but also reveal the new engine, as per the old R100 RS.

As the K was conceived as a new beginning for BMW Motorrad, a great deal of time and effort was also expended on the new bike’s styling and equipment. Following the success of the boxer RS, the new K100 RS would be similarly half-faired to maximize aerodynamic efficiency, yet also leave the engine on show and to aid its cooling.

Design chief Klaus-Volker Gevert and his team, while taking influences from historic racing BMW bikes, also adopted the more angular style of BMW cars of the era, particularly the M1 sports coupé launched in 1978. Through almost endless drawings and design studies, they created a truly modern but practical and comfortable silhouette that was also transferable through roadster, sports tourer and fully faired touring variants.