Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

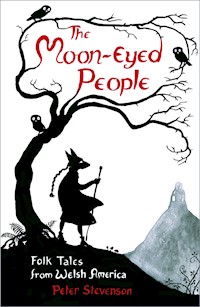

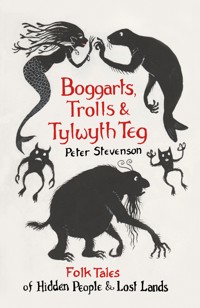

The Grimms called them The Quiet Folk, in Māori they are Patupaiarehe, in Wales Y Tylwyth Teg: hidden people who live unseen, speak their own languages and move around like migrants, shrouded from our eyes – like those who lived in the utopian world of Plant Rhys Ddwfn off the west Welsh coast, where this book begins. In mythology, lost lands are coral castles beneath the sea, ancient forests where spirits live, and mountain swamps where trolls lurk. Strip away the mythology, and they become valleys and villages flooded to provide drinking water to neighbouring kingdoms, campsites where travellers are told they can't travel, and reservations where the rights of first nations people are ignored. The folk tales in this book tell of these lost lands and hidden people, remembered through migrations, dreams and memories.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 303

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedicated to Nika, Cheuk, Toby and Tilly

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place,

Cheltenham GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Peter Stevenson, 2021

Illustrations © Peter Stevenson, 2021

Foreword © Moira Wairama

Quote on p190 © Cailtlin Tan

Quote on p200 © Tony Hopkins

The right of Peter Stevenson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9833 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

‘There’s no identity problem, only a problem of identity.’

Tony Hopkins, black Cherokee storyteller, actor and poet from New Zealand

Contents

Foreword by Moira Wairama

Introduction

1. The Crow and the Canary: Part One

Cymru, Wales

2. The Silkie Painter

Alba, Scotland

3. Boggart Hole Clough

Lancashire

4. The Glashtyn

Ellan Vannin, Isle of Man

5. The Sceach and the Seanchaí

Éireann, Ireland

6. The Stonewaller and the Korrigan

Breizh, Brittany

7. Schneeweißchen und Rosenroot

Deutschland, Germany

8. A Tale of Tales

Italia, Italy

9. Sjökungen and the Troll Artist

Sverige, Sweden

10. Trolls

Norge, Norway

11. Ulda Girl and Sámi Boy

Sápmi

12. Huldufólk and the Icelandic Bank Crash

Ísland, Iceland

13. Otesánek and the Jeziňka Girls Who Steal Eyes

Česká republika, Czech Republic

14. Nita and the Vampir

Řomani ćhib, Roma

15. The Copper Man

Удмуртия, Udmurtia

16. The Girl Who Became a Boy

Shqipëria, Albania

17. The Hidden People of Anatolia

Anatolia, Anadolu

18. The Bewitched Camel

Syria

19. A Tale from the Tamarind Tree: The Djinn Girl

Senegaal, Senegal

20. The Hare and the Tortoise (But Not that Tale)

Moris, Mauritius

21. Weretiger

Khasi

22. Yakshi

Kerala

23. The Fox and the Ghost

Zhōngguó, China

24. Yōkai

Nihon, Japan

25. Patupaiarehe

Aotearoa, Māori, New Zealand

26. River Mumma

Jamrock, Jamaica

27. The People Who Could Fly

Gullah, Geechee

28. The Woman Who Fell in Love With a Pumpkin

Bhutan, New Hampshire

29. Appalachian Mister Fox

Appalachia

30. Cherokee Little People (Yunwi Tsunsdi)

Cherokee

31. We’re Still Here

Duwamish

32. The Crow and the Canary: Part Two

Cymru, Wales

Epilogue: Plant Rhys Ddwfn

Bae Ceredigion, Farraige na hÉireann, Irish Sea

Bibliography

Foreword

What a delight it was to have Welsh storyteller and friend Peter Stevenson visit our local marae to share Welsh stories alongside my partners’ African and Native American tales and myths and legends from my own land Aotearoa/ New Zealand.

Although our stories came from different hemispheres and cultures, we recognised in each other’s tales the familiar characters of the trickster, the fairy folk and those wise, wily or sometimes frightening mythical creatures such as our Aotearoa taniwha. We found that by sharing our different stories we were not only entertained but we also were connected.

For me as a Pākehā New Zealander (a person descended from New Zealand settlers, many of whom were English, Welsh, Irish and Scottish), hearing Peter tell traditional stories using Welsh phrases and words that some of my ancestors would have recognised was both moving and thought provoking.

The fact that the indigenous people of Wales and Aotearoa were persecuted for speaking their own language, practising their cultural traditions and telling their own stories gives both cultures a shared experience. Today, as people of many cultures work to ensure their languages and traditions survive in an ever-changing world, storytellers such as Peter Stevenson ensure the stories will also survive. In this, they do us all a great service and are truly taonga (something precious).

Moira Wairama

Introduction

As a scruffy child, I liked clambering over the remains of the 150 iron-age stone roundhouses in the Giants’ Town on the summit of Tre’r Ceiri on Pen Llŷn in north-west Wales, because from there I could see the whole wide world. Well, maybe not all of it, but the Wicklow Hills 60 kilometres to the west in Poblacht na hÉireann, the mountains of the English Lake District in the faraway north and the island of Ellan Vannin in the Irish Sea. And out there in Cardigan Bay were two mythical lands, the submerged city of Cantre’r Gwaelod that illuminated the sea with the setting sun, and the utopian land of Plant Rhys Ddwfn, the Children of Rhys the Deep, a folk philosopher’s dream of a better world (read the full story in chapter 34).

However, all these mystical lands were usually hidden by what my mam called ‘The Steam’, or more poetically, ‘Y Brenin Llwyd’ (the Grey King), a thick mist that sits on top of Tre’r Ceiri and prevents anyone seeing beyond the ends of their noses. Undaunted, I learned that if I squinted and used my imagination, I could see a town full of hidden giants, several faraway countries, a lost submerged land and a forgotten utopia, and all were equally real in my childhood mythology.

Below Tre’r Ceiri is the mountain village of Llithfaen, where three generations ago the older folk told tales in Welsh as chwedlau, a weaving together of myth, conversation and gossip. They left the village every Wednesday, packed like sardines onto Glyn’s old Leyland Tiger bus that rattled along the single-track road to the Wednesday market in Pwllheli. What it lacked in suspension it made up for in stories and chickens. After the granite quarry closed in 1964, the stoneworkers’ houses in Nant Gwrtheyrn fell derelict and were squatted by hippies who knew little of the stories of the land. The coastal villages were becoming retirement homes and holiday camps, house prices were rising, and young people were leaving for jobs in cities over the border. People were vanishing.

The giants watched from the mountain as Carl Clowes, the local doctor, founded Antur Aelhaearn, the first community co-operative in the UK, and gave me my first job on leaving college, painting designs on the pottery and firing the kiln of an evening. The deserted village of Nant Gwrtheyrn was renovated and transformed into the National Welsh Language Centre. The land was reborn, Rhys Ddwfn’s utopian dreams had come true, and I learned that people could be giants, too. Myths and real life were intricately intertwined.

Back in the late 1800s, Griffith Griffith, a chapel man from Edern, was crossing the heather below Tre-r Ceiri, when he saw a crowd of little men and women walking towards him, speaking a language he didn’t understand. He wasn’t afraid, so he stood by the ditch to let them pass. He didn’t know where they were from, so he called them ‘Tylwyth teg’ – fairies.

Elis Bach, a farmer’s son from Tŷ Canol in Nant Gwrtheyrn, was thought to be a changeling child, because his legs were so short his body almost touched the ground. One day, he and his dog Meg saw some men herding stolen sheep up the corkscrew road. He jumped out on them, did a weird dance, and chased them off. Elis was no supernatural creature; he was born in the village and spoke Welsh. He was Tylwyth teg because he was different, like those visitors who treated Welsh speakers as if they were from another planet.

Time passed, and I became a book illustrator and storyteller, and these skills allowed me to meet people from cultures across the world and hear tales of their lives and lands. One such encounter led to the writing of this book. For thirty years I’ve worked with the New Zealand publisher, Sunshine Books of Auckland, illustrating stories by great children’s writers like Joy Cowley and Margaret Mahy. Although a stranger back then, my visual storytelling has now become a small part of the lives of two or three generations of Pākehā, Māori, Pasifika and Chinese children.

At Christmas 2019, my friend Moira Wairama, Pākehā storyteller and writer, invited me and my son to her local marae in Stokes Valley where I was to tell tales of the Tylwyth teg. Moira introduced me to stories of the Patupaiarehe, the little people of the Aotearoa bush, while her partner, storyteller and actor Tony Hopkins, is rooted in the storytelling tradition of the Yunwi tsunsdi, the Cherokee little people.

While Patupaiarehe, Yunwi tsunsdi and Tylwyth teg may appear to be sisters from three separate continents, they each grew from their own landscapes and cultures, spoke their native tongues, and travelled in the darker margins of our minds to meet in New Zealand as stories.

A tangi, a Māori funeral, was taking place next door, so we paid our respects to the bereaved family who sat on cushions around an open casket surrounded by the painted and carved wooden walls that depicted the myths of the Stokes Valley iwi. We were introduced with spontaneous stories and songs in a moment of shared community and mythology that celebrated death within life. This was the root and branch of visual storytelling; a moment of transition no international zoom event could ever replicate. And I understood what it was like to be Tylwyth teg – from the Otherworld (read more in the chapter Patupaiarehe).

In mythology, lost lands are coral castles beneath the sea where mermaids swim, ancient forests where spirits live among the trees, mountain swamps where trolls lurk, thinly veiled dimensions haunted by ghosts, underground hell worlds full of demons, and darkness where fairies fly on gossamer wings. Strip away the mythology, and lost lands become valleys and villages flooded to provide drinking water to neighbouring kingdoms, inner cities where people exist on fairy money, closed doors that conceal tales of domestic abuse and mental health, campsites where travellers are told they can’t travel, migrants displaced by war and hunger, and reservations where the rights of First Nations people are ignored.

Stories of encounters with those from the otherworld are about Them and Us, and ask simple questions, ‘Are you scary or friendly? Do you speak our language? Should we welcome you or build a wall and keep you away?’ Look into a face, and we make assumptions about gender and race, but only when we hear their stories do the walls between us tumble down. No flimsy border can stop a good story from crossing over, rooting itself and growing leaves in its new home. African mermaids, Chinese fox fairies and Indian weretigers all flourish in Wales.

An international approach to folktales through collaborations, permissions and acknowledgements helps understand the nature of ‘otherness’. Yet there must be sensitivity to appropriation, for folktales are a living reflection of their own cultures, people and landscape, and a story torn from its context is merely a text. Yet it’s important to find ways to surmount what Bong Joon Ho, director of the South Korean film Parasite, called ‘the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles’.

The tales in this book have grown from conversations with storytellers, writers, artists, academics, historians, educationalists, friends and family across the world, encountered on my travels and in my small multicultural Welsh hometown. In the tradition of storytelling, that delicate balance between art and academia, I tell the stories in my own words while keeping close to the emotional and physical landscapes of the tellers who are themselves woven into the chapters. And a very special thanks to my dear friend Veronika Derkova for reading through the manuscript and for the countless inspiring conversations in her bee garden.

In my mythology, all stories begin in West Wales, so this tour of lost lands and hidden people starts with a changeling child who may have been a famous poet, followed by a Scottish selkie who came from the sea to save an old fisherman, the Korrigan who stopped a Breton stonewaller building across their unseen land, the Irishhidden people who prevented the felling of fairy hawthorns, Scandinavian trolls from a misunderstood native culture, a poor bewitched camel infatuated with a wealthy Syrian princess, a Mauritian hare who took whatever he wanted like colonialists before him, the huli jing from the invisible male dreamworld of old China, the Gullah people of North Carolina and West Africa who knew how to fly, the Duwamish of Seattle who officially don’t exist, and back to the utopia of West Wales to meet Morwen, the mermaid who inspired a renowned writer in the western world.

Oh, and not forgetting the nasty Jeziňka girls from the Czech Republic who steal people’s eyes so they can’t see what’s in front of their noses, just like the mist on the Welsh mountains.

1

The Crow and the Canary: Part One

CYMRU, WALES

Three years ago, the Welsh Government’s tourism department designated 2017 as Flwyddyn Chwedlau Cymru, the Year of Legends. Wales was given a makeover as a mythological land where King Arthur strode like a giant, magicians mixed potions in cauldrons on mountaintops, mermaids swam through plastic-free seas, and impoverished storytellers were offered unexpected employment. However, hidden behind the marketing was another storytelling tradition that mixed legends with local gossip, spontaneous wit and contemporary injustices.

In this looking-glass world, mystical ladies who lived beneath lakes were replaced by people displaced from villages flooded to build reservoirs to supply drinking water to cities over the border. And these tales of lost lands and hidden people were told in the native Welsh language, spoken by people and mermaids alike.

This story begins with a translation of a Welsh-language fairy tale from the writer, illustrator, and educator Myra Evans, from Ceinewydd, on the coast of Ceredigion, and is followed by a mostly true tale pieced together from conversations with her daughter, Iola Billings, and many walks in the shared landscape of both tales. Myra’s archive is the richest collection of oral folk tales in Wales, yet she is barely remembered as a footnote in the life of an internationally famous poet who lived his life as the hero of one of her stories.

A woman was wandering, lost and lovelorn, in the Llwynwermwnt woods near Ceinewydd, when she sensed someone behind her. She turned and there was a man, hair in golden ringlets, eyes green as spring pools, and a smile of pearly white milk teeth. He kissed her hand, held her round the waist and laid her down on the mossy ground. When she came to, he had done as all creepy men who lurk in the woods in fairy tales always do. He’d vanished.

All that day she searched for him and all the following day, all that week and the following week, and all that month till nine months passed, when she gave birth to a beautiful baby boy, curling gold hair, spring green eyes, and pearly white milk teeth. Her anger for the man who had abused her melted into love for her fairy child.

The woman lived at the Llwynwermwnt Farmhouse outside Ceinewydd. She sang as sweetly as a canary, but her husband was a simple, stolid man who croaked like a crow. He knew the names of all his sheep, but not the name of the child he assumed was his.

Late one afternoon, the woman was feeding her baby when her pap ran dry, so she took a jug and went outside to milk the cow. It mooed agitatedly and kicked at the pail. As she returned to the farmhouse, she noticed the door was ajar and she thought she’d closed it. The fire blazed in the hearth, and she knew she’d dampened it down. Her baby sat upright in his wooden cradle, gnashing and grinding his teeth, gurning his face into weird contortions and staring with eyes the colour of autumn, his golden locks turned ash brown.

She wrapped him up warm in his cradle and ran down the hill to an old ramshackle cottage overlooking the sea at Banc Penrhiw, encircled by enchanter’s nightshade and wild garlic. She knocked on the oak door and there stood old Beti Grwca, a thousand wrinkles around her eyes, a single grey hair in the middle of her chin, and a solitary yellow tooth that wobbled unnervingly in the breeze from her breath.

‘Dewch i mewn, cariad,’ old Beti ushered her in. ‘Bara brith? Paned?’

The ochre walls were lined with sagging shelves filled with green and brown bottles. Beti laid the table with fruit bread and a pot of thin Tregaron tea.

‘Help yourself, and don’t mind the cat and her little ways. Now what can I do?’

As the woman explained, old Beti wrinkled her eyes and pulled on the one grey hair in the middle of her chin and said, ‘Cariad, this may not be your babi. It may be an anwadalyn, a changeling child, left by the otherworld!’

Beti shuffled over to the dresser, took a large duck egg, pricked both ends, blew out the contents, and stuffed it with bread, cheese and milk.

‘In the morning, break this egg onto seven plates, make sure your babi is watching, say nothing, do nothing, come and tell me what you hear and see.’

The woman took the egg and walked home over the hill with her moonlit shadow following behind. The cow mooed agitatedly in the farmyard, the door was ajar, and she was sure she’d closed it, the fire blazed in the hearth, and she knew she’d dampened it down. Her baby spat into the fire and stared through wide autumn eyes with the knowledge of a thousand and a half years. Dark thoughts danced in her head. If this was an anwadalyn, should she drown it in the deep dank pond at Nantypele farm?

In the morning she laid the table with seven plates, broke open the egg, and a feast of bread, cheese and milk filled the table. Brown eyes followed her round the kitchen as she stoked the fire, stared into the flames, and listened:

Mesen welais cyn gweld derwen

Gwelais wy cyn gweled cyw

Ond ni welais fwyd i fedel

Mewn un plisgyn yn fy myw

[‘I saw an acorn before an oak, I saw an egg before a chick, but I never saw food from one shell.’]

The woman ran to old Beti, who wrinkled her eyes, pulled on the one grey hair in the middle of her chin, and said, ‘Cariad, this is an anwadalyn. Come with me, say nothing, do as I say.’

Beti took the woman’s hand and they followed their shadows over the hill to the Llwynwermwnt farmhouse. The cow was hysterical, the door banged on its hinges, the fire blazed in the hearth, and the baby sat upright in its cradle. It ground and gnashed its teeth and it’s bulging brown eyes stared straight into their souls.

Beti snatched it up, ignored the screams and curses, and scurried over the hill to the Nantypele farm pond as it gnawed her shoulder. She thrust it into the woman’s arms and told her to hurl it into the dank depths. The woman stared into its bloodshot autumn eyes, and in that moment, she knew this was not her baby. She hurled it with all her strength, and as it screamed through the air and hit the surface, the waters boiled and the Tylwyth teg appeared, dressed in red rags and with shaggy red hair, and they dragged their wayward child into the depths, leaving a clinging coldness in the air.

Old Beti led the woman by the hand back to Llwynwermwnt. The cow was contentedly chewing the cud, the door was carefully latched, the fire dampened in the hearth, and there gurgling in his cradle was her golden-haired baby. She held him to her breast and kissed him, and never noticed that while one eye was green as the spring, the other was still brown as autumn.

Myra Evans was born in 1883 in Ceinewydd, not far from the Llwynwermwnt farmhouse, at midnight between All Souls and Calan Gaeaf, the first day of winter in the Welsh calendar, when the veil between this world and the other is at its thinnest and those from the otherworld pass through and make mischief. Myra stared at the world through her brown eyes of autumn and grew into an inquisitive girl who loved to dress up as a mourner and attend funerals, once in a red dress amongst the crow black, always walking a tightrope between her two worlds. She loved to sing, but she squawked like an old crow.

Her father Thomas was a fisherman, captain of the Rosina, who had lost all his five brothers at sea. Myra was his fish-girl. She sat beside him on the pier gutting the herring and mackerel while he told her fairy tales learned from the old sea captains of the town. She wrote down his stories and kept them in a biscuit tin under her bed to read while he was away at sea. Here were stories of red-haired mermaids, vanishing harpers and fleet-footed fairy fiddlers, characters from the West Welsh Otherworld familiar to everyone 100 years ago, a charmed state where time passed in the blink of a crow’s eye or the length of an endless final heartbeat, where you could vanish as easily as a language. There were few kings and princesses in Myra’s world.

Myra married her childhood sweetheart, Evan Jenkin Evans, a nuclear physicist from Llanelli who studied in Manchester with Ernest Rutherford. Their firstborn David died young, while the second, Aneurin, grew into a mischievous child, who climbed out of his bedroom window in Chorlton when he was 3 and was found eating an ice cream in a city-centre cinema by the Manchester Police, who couldn’t understand a word he said as he spoke only Welsh.

In the early 1920s, Evan was offered work in the Physics Department at the fledgling Swansea University, so the family moved to suburban Sketty, with its semi-detached villas and stained-glass windows, where people spoke posh. Sex sounded like the sacks that coal was delivered in.

Myra taught Welsh in the Swansea schools when the language was discouraged by the authorities, she wrote and illustrated the first Welsh language primer and persuaded Foyle’s of London to publish it, she worked for the BBC telling nature stories in Welsh on the radio, and she published a small collection of her father’s fairy tales, Casgliad o Chwedlau Newydd, to raise money for the restoration of the Tabernacl Chapel roof in Ceinewydd. One of those tales was the ‘Anwadalyn Llwynwermwnt’.

Aneurin went to Swansea Grammar School with the mischievous son of Myra’s neighbours in Sketty, David and Florence Thomas. David, an English teacher at the school, loved Welsh mythology yet taught his son in English, while Myra spoke to her boy in his native language.

The young Thomas was molly-coddled by his mam, stole sweets, fell out of trees, broke bones and was as cheeky as any changeling child. He had a head full of golden curls, eyes of autumn brown, and they named him Dylan.

Dylan had all the disadvantages of a happy childhood. He decided to be a poet, a hard-living bohemian looked after by rich crows – soft, silly ravens, he called them. He had all the qualifications. He was an outsider who wrote about himself, rather than the romance of the Welsh landscape.

By 1934, Dylan had lost his jobs at the local newspaper and the Swansea Little Theatre, his first book of poetry had been accepted by a London publisher, and he had a girlfriend in Battersea. He left the comforting arms of the Mumbles Mermaid and crossed the border into the neighbouring kingdom, where he slayed the giants of the London literary world and charmed the dragon, Dame Edith Sitwell, who favourably reviewed his book.

He attended the court of King John, the painter Augustus, where he met the golden-haired Princess Caitlin and wooed her with words, not swords. He was left lying in a car park in Carmarthen after the king found him in a compromising position with the princess on the back seat of his car. He spent the summer of 1935 in a remote cottage in Donegal, writing, walking, fishing, running up debts, insulting the locals and trying to dry out. He was joined for a fortnight by Geoffrey Grigson, then editor of New Verse magazine, who referred to him as ‘The Swansea Changeling’, left by the Otherworld under a foxglove.

In September 1944, the changeling child, his golden-haired princess and their two young children left the land of falling bombs for the wild West Welsh coast, and by one of those curious coincidences you only find in fairy tales, in the same month of the same year, Myra Evans and her mischievous son and youngest daughter moved into a blue bungalow down the lane.

The story continues in ‘The Crow and the Canary, Part Two’ on page 207.

2

The Silkie Painter

ALBA, SCOTLAND

I first heard this story forty-odd years ago as a post-grad at Leeds University’s Institute of Dialect and Folklife Studies, which was hidden away in the basement of a terraced house, at least until its closure in 1984. I had completed my art degree, and had transformed into an academic folklorist, and this new skin was itchy. The head of the institute, Stewart Sanderson, had been the archivist at the School of Scottish Studies in Edinburgh, and he introduced me to the story of the selkie artist, a tale of split identity and misunderstood people, which in that moment spoke volumes to me. The storyteller was the legendary Scottish traveller, Duncan Williamson.

Duncan was born in 1928 in a traveller camp in Argyll, one of sixteen children to parents who couldn’t read and a people who were cruelly persecuted and vilified. He went to school but left aged 13 to work as a stonemason, horse dealer, drystone dyker, farmhand, once as a boxing instructor, and for thirty days as an inmate in Perth Prison for breaking a man’s jaw. He jumped the broomstick with his first wife Jeannie when she was 16, and they had seven children, but these are mere facts.

Duncan famously said, ‘Never let the truth stand in the way of a good story’, and he also told storytellers to look over their shoulders at the person who told them the tale, for behind them would be all the previous tellers. I learned to always acknowledge sources, as academics are trained to do. Though I never got the hang of footnotes.

Duncan disapproved of excess academia, at least until he married the folklorist and musicologist Linda Headlee from the School of Scottish Studies, who arrived one day to interview him. She encouraged him to write down and publish his stories and contact the storytelling festival world. So, his tales of cheeky Jack and the fairies turned him into a man of two worlds.

He published Tales of the Seal People in 1992, a collection of silkie stories pieced together from tales he knew from the traveller community. By then, I’d shed my academic skin and returned to the world of illustration and books. And almost thirty years later, maybe Scotland is preparing to tear off the skin of a disunited kingdom and swim free as a silkie.

In a stone cottage on the west coast of Scotland lived two old fisherfolk, John and Mary, who farmed the sea, salted and dried the herring, and sold them at the Wednesday market. On warm evenings, they sat on the shingle outside their front door and mended the nets after the seals had bitten holes in them to eat the fish inside. John hated the seals.

‘Those seals are taking my living,’ he said, ‘There’ll be no food on the table, and what will we do then? They should all be shot, those seals.’

‘Oh, don’t make a fuss,’ said Mary, ‘the sea provides food enough for us all.’

Well, the old fisherman grumbled as Mary shooed him indoors, sat him down at the kitchen table and placed a bowl of fish soup in front of him. He splashed it down his sweater in between mouthfuls, while he complained it might be his last meal, thanks to those seals.

One day, Mary had filled her leather apron with dulse, red seaweed that she dried and sold at the market, when she spotted a shape on the shoreline. She hurried towards it, thinking it might be a body, only to find a seal pup staring up at her with big saucery eyes. She looked around for its parents, for grown seals can be fearsome creatures when they have a baby, but there were none to be seen. ‘Poor little orphan,’ she thought, as she wrapped it in her apron with the dulse, hurried back to the cottage, and laid it in the old wooden cradle John had carved before her miscarriage. She covered it in the red patchwork quilt from their bed, fed it a small mackerel, and listened as the wind rattled the loose panes.

When the old fisherman came home, he was still grumbling about the holes in his nets, when he saw the seal pup.

‘What’s that doing here? In my cradle! Wrapped in my quilt. Eating my fish. Where’s my gun?’ he blustered.

Mary had hidden the gun in the woodshed.

‘Now calm yourself, John,’ she said. ‘It has no parents, and it would have died on the beach if I hadn’t brought it home.’

‘Well, let it die,’ he grumbled, ‘or it will have babies, and they will eat all my fish, too.’ And he spat into the fire.

‘Calm down,’ she said. ‘They aren’t all your fish, they are to be shared.’

That evening, the old man gnashed his teeth and swore he would kill every seal in the sea. They were preparing for bed when there was a knock on the door.

John said, ‘Don’t answer. It might be the bailiffs come to evict us and ship us to America.’

Mary told him not to be foolish and she opened the door to a tall young man with dark curling hair, thick on top and short at the sides, a long nose and high cheekbones. He wore a navy fisherman’s jumper with a knitting pattern unique to his home port and an initial embroidered into the hem, to identify his body if it washed up on shore. John didn’t recognise the pattern.

The young man apologised for calling so late, but he was looking for lodgings in the town and there were no beds to be had. The landlord suggested asking here. He only needed a small room, as he would be out all day and gone inside a week. He was a painter, intent on capturing the landscape of the seashore on canvas. He would be no trouble at all. His name was Iain.

Mary said they would rent him a room, and John added they were short of money because those pesky seals were eating all his profits. Mary elbowed him under the ribs, and they led Iain upstairs to a bedroom.

‘This is our room,’ whispered John, ‘where will we sleep?’

Mary replied, ‘In the child’s room. Hush now.’

Iain declared the room perfect and assured them he would not make a mess. He only had a portable easel, some canvases, a sketchbook and a water jug for rinsing his brushes, and he mostly worked outdoors as he drew from life. He gave them a week’s rent, and hands were shaken. Mary said Iain must help himself to porridge and herring for breakfast, and he could join them for an evening meal. The old man told him not to help himself to all the fish, though, as those sea …’

Mary elbowed him again and he stifled the pain. And she couldn’t help but repeat Iain’s name to herself.

The following day, Iain was up and out early, and returned in the evening at the same time as John. They had fish and tatties, and lit a fire, and Iain told them tales of the mischievous sidhe and broonies from MacGregor’s The Peat-Fire Flame, and he sang the old ballad of Tam-lin, the story of Janet, a young woman who has a child with an otherworldly man in the forest. Songs, like folk tales are full of strange, enchanted, abusive men who appear from nowhere.

Well, the old couple loved Iain’s stories, and John fetched his bottle of finest malt whisky and offered a very small dram. For three evenings, Iain told tales of his life at sea, of the kelpies and wulvers, and he showed them drawings of the weirdest fish. John asked what they tasted like, and Iain described it as a cross between a crookit mouth and a tammy harper. John wanted to know where to catch them, and Iain said the seals would lead them to the fishing grounds the following day. The old fisherman grumbled it was about time those seals made themselves useful, and he shook his fist at the pup in the cradle by the fire.

The following morning, the sky dawned clear, Mary packed a box with fresh oatcakes, plum jam and dulse, and told them to remember to offer a little to the sea. The two men sailed on the early morning tide, and soon their nets writhed with herring and mackerel and the pots rattled with lobsters and crabs.

Iain said they had caught enough, but John insisted on sailing further, for he wanted to taste these strange new fish. Iain looked up, there was a storm brewing, but the old man couldn’t see the fish for the sea and he set sail. When the storm hit, a wave rocked the boat and Iain was tossed overboard.

John held out his hand, but the sea churned, and Iain had vanished. The old fisherman turned the boat for home, but another wave hit, and he too was drawn under the waves. He came up and gasped for air, once, twice, and he knew when he sank for the third time he would never see the sky again. He had thought of this moment and accepted his fate, but as he sank into the boiling waters, two arms wrapped around his waist.

When he awoke, he was lying on the shingle below his cottage. The storm had blown out, and Mary was pressing water from his lungs. He asked if Iain was safe, but Mary had not seen him. She lifted her man in her arms and carried him home, laid him down on Iain’s bed, wiped the fever from his brow and fetched a doctor from the town.

John told Mary and the doctor what had happened and asked again if there was any sign of Iain. The doctor was curious to know who this mysterious young man was, so they told him how Iain was sent to them.

The doctor picked up a small canvas leaning against the wall behind the door. It was a painting of the seashore with the cottage in the background and an old woman collecting dulse in a leather apron, and in her arms was a seal pup. Mary watched the doctor’s eyes to see if he understood. For she had always known that Iain was one of the unseen, a seal man, a silkie. The silkies always came when lessons were to be learned.

The doctor declared it a fine painting but explained that as far as he knew there had been no strangers in the town. He stared knowingly at Mary. She smiled, thanked him for his kindness and pushed him out the door, for she was sure he had many sick folk in need of his services.