Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

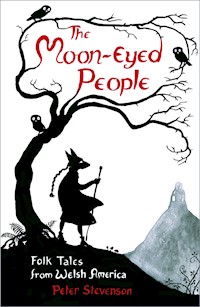

A lone man wanders from swamp to swamp searching for himself, a wolf-girl visits Wales and eats the sheep, a Welsh criminal marries an 'Indian Princess', Lakota men re-enact the Wounded Knee Massacre in Cardiff and, all the while, mountain women practise Appalachian hoodoo, native healing and Welsh witchcraft. These stories are a mixture of true tales, tall tales and folk tales, that tell of the lives of migrants who left Wales and settled in America, of the native and enslaved people who had long been living there, and those curious travellers who returned to find their roots in the old country. They were explorers, miners, dreamers, hobos, tourists, farmers, radicals, showmen, sailors, soldiers, witches, warriors, poets, preachers, prospectors, political dissidents, social reformers, and wayfaring strangers. The Cherokee called them: 'the Moon-Eyed People'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 249

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedicated to the Kemps of West Virginia and the Andersons of North Carolina

First published 2019

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Peter Stevenson, 2019

Illustrations © Peter Stevenson, 2019

The right of Peter Stevenson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9270 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

‘The Cheerake tell us, that when they first arrived in the country which they inhabit, they found it possessed by certain moon-eyed people, who could not see in the day-time. These wretches they expelled.’

Benjamin Smith Barton, New Views of the Origin of the Tribes and Nations of America, 1797.

‘I have heard my grandfather and other old people say, that they were a people called Welsh … a Frenchman, who lived with the Cherokees … informed me, ‘that he had been high up the Missouri, and traded several months with the Welsh tribe; that they spoke much of the Welsh dialect, and although their customs were savage and wild, yet many of them, particularly the females were very fair and white, and frequently told him, they had sprung from a white nation of people; also stated they had yet some small scraps of books remaining among them, but in such tattered and destructive order, that nothing intelligible remained.’

John Sevier, Governor of Tennessee, letter to Amos Stoddard, 9 October 1810.

Contents

Introduction

1 Wolf-Girl Visits Wales

2 The Moon-Eyed People

3 Where the Welsh Came From

4 Lone Man Coyote

5 The Bohemian Consul to Cardiff

6 When Buffalo Bill Came to Aberystwyth

7 The Cherokee Who Married a Welshman

8 John Roberts of the Frolic

9 The Legend of Prickett’s Fort

10 Ghosts of the Osage Mine

11 Brer Bear and the Carmarthenshire Muck Heap

12 In Search of Fanny the Barmaid

13 The Devil and the Mothman

14 Owl-Women and Eagle-Men

15 Hoodoo and Healers

Bibliography

Introduction

Alone man wanders from swamp to swamp searching for himself, an owl remembers she was once human, a woman is in love with two moons, a war over land enclosures leads to mass migration, a skunk chases a greedy bear from his home, a wolf-girl visits Wales and eats the sheep, a Brecon preacher walks on the Trail of Tears, Welsh weavers make cloth for enslaved people, a mining settlement in Appalachia is described as being unfit for pigs, a spear-fingered monster is defeated with menstrual blood, a Welsh criminal marries an ‘Indian Princess’, Lakota men who witnessed Wounded Knee re-enact the massacre in Cardiff, and all the while mountain women practise Appalachian hoodoo, native healing, and Welsh witchcraft.

These stories are a mixture of true tales, tall tales and folk tales that tell of the lives of migrants who left west Wales and settled in and around Appalachia, of the native people who were already living on the land, the enslaved people who had been forcibly brought there, and those curious travellers who returned to their roots in the old country. They were explorers, farmers, hunters, miners, dreamers, hobos, radicals, showmen, singers, sailors, soldiers, storytellers, liars, witches, warriors, poets, preachers, tourists, colonists, political dissidents, social reformers, and wayfaring strangers.

Those who left Wales had little idea of what lay ahead for them. Benjamin Williams of Mynydd Bach in Ceredigion was about 17 when he sailed for America:

Having sold the farm in the summer of 1838, we prepared to come to America … we set out in carts from Lledrod to Aberayron: we were there for many days … 175 Welsh people ready to embark for Liverpool in three sloops … we had to wait a few days before boarding the sailing ship. People over 18 years paid £20; from 10 to 18 half-price, under five came free … the doctor came aboard and examined us to see whether we were fit for the voyage and decided that many of the children weren’t fit to sail … Some ill people were hidden and when they were discovered it was too late to turn back … 17 children, and all those under 10, died, great sadness, Rahel crying for her children. Six weeks of sailing through several storms; we lost the course for Baltimore and sailed towards Cuba before the elements subsided and we got back on to the correct course.

When the migrants landed in Baltimore or Boston, they were sometimes renamed by the immigration authorities, who couldn’t pronounce or spell their real names. Those who spoke only Welsh were confronted with languages and dialects from Scotland, Ireland, England, Italy, Romania, Germany, Sweden, Hungary, Holland, Greece, Poland, Russia, Slovakia, Bohemia, French Canada, Latin America, and all parts of Africa and Asia. They crossed the endless ridges of the Allegheny Mountains with belongings tied to wagons and pack mules, and negotiated the purchase of land from companies who had taken it from people who already lived there.

Many of the Welsh settled in Pennsylvania, where they encountered the Shawnee, indigenous people who spoke an Algonquin language. From Pittsburgh, they moved down the Ohio and Monongahela Rivers through West Virginia into North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee, the area known as Southern Appalachia. Here they met the Aniyunwiya, who the colonists called Cherokee, a corruption of a native word meaning ‘people who speak differently’. They called themselves Tsalagi, and told stories in an Iroquoian language, Tsalagi Gawonihisdi; tales the invaders couldn’t begin to understand.

They encountered enslaved people and their descendants, brought over on boats against their will, packed like sardines in the cruellest conditions, bought and sold like cattle, prevented from speaking their own languages. These people told their stories in a Black English language based on the shared African belief in ‘Nommo’, the idea that a word when spoken was the power of life, and its beauty told an oral history of forced migration.

Folk tales in all cultures carry memories of migration. Peter Henry Emerson, son of an American plantation owner in Cuba, published a little-known story that was told to him near Menai Bridge, Ynys Môn, in 1891. It tells of how the ancestors of the Welsh escaped persecution and taxation in Persia, built a great city called Troy, made their way through feast and famine to Brittany, and over the water to Brython, where they were pushed ever westwards by successive invaders.

There are migration narratives in the fourteenth-century Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch (White Book of Rhydderch), in the tales known as Pedair Cainc y Mabinogi. In the second branch of the manuscript, Branwen, sister of the King of the Brythons, is given by her brother Bendigeidfran to the King of Ireland in an arranged marriage designed to broker peace between the two countries. She is forced to live in a strange land and ordered to work in the kitchens, where she is slapped round the face with a slab of meat each day, her only friend a starling who flies over the sea with messages for her brother. In the third branch, following the wars with the Irish, the King’s brother, Manawydan, emigrates to England to find work as a craftsman, but he is too skilled at his job and is forcibly moved on, time and time again, until he finally returns home. He turns to farming and grows three fields of corn, only to wake up each morning to find the ears of his golden corn have been eaten by a horde of proletarian mice. In the fourth branch, Blodeuwedd, created from flowers by a man to satisfy the needs of his son, undergoes an internal migration, from woman to owl, and is banished to the dark as punishment for having desires and thoughts of her own.

The tale of a woman turned into an owl is not uniquely Welsh. It also occurs in a story from the Turtle Island Liars’ Club, told by Hastings Shade, former deputy chief of the Cherokee Nation. Another member of the Liars’ Club, Sequoyah Guess, tells a migration story of how the ancestors encountered a group of mound builders in North Carolina and Ohio, discovered they were cannibals, defeated them in a war, and began building mounds themselves. There are mound cities all across Southern Appalachia, built over 2,000 years ago, when Wales and America were only dreams.

The Cherokee also have stories about the fairies, ‘yunwi tsunsdi’, ‘the little people’. The author Robert Conley writes about John Little Bear, a renowned healer, who believed that whenever he couldn’t find something he was looking for, it was those ‘danged little people’ who were always hiding things from him. And while the little people were mischievous, they also looked after anyone lost in the woods. Little Bear left them whisky and honeycomb as a thank you, and in return they gave him a song to call them up when he needed help.

In Wales, a farmer in the hills of central Ceredigion told me that the ‘tylwyth teg’ had visited his farm all his life, sometimes helping with the chores, sometimes playing tricks, hiding things, but he couldn’t say too much in case they never came again. These memories of the little people from Ceredigion and Cherokee are not ancient, they are both twenty-first century.

None of this should be a surprise. Folk tales have always followed people around like faithful old dogs. They migrate across geographical, political, and imaginary boundaries with no need for passports, hidden in the minds of explorers and refugees. The West Virginia folklorist Ruth Ann Musick’s extraordinary collection of European folk tales, Green Hills of Magic, contains many stories from southern Appalachia collected from first-, second-, and third-generation settlers who came over to work in the mines in the early 1900s. Some were told by and about Welsh colliers, who were always ready with a joke and a shaggy dog story. These were the folks the Cherokee called ‘the Moon-Eyed People’, for they were small and pale, lived underground, and could see in the dark.

In the storytelling traditions of both Appalachia and Wales are shared folk tales. The Welsh gypsy fiddler Matthew Wood told many fairy tales of the fantastical adventures of an archetypal cheeky boy called Jack, who fights giants, defeats dragons, and marries princesses. Matthew told his stories in the Romany language, often at gatherings on one of his favourite haunts, Craig yr Aderyn (Bird Rock), near Abergynolwyn.

Appalachian cultural icon Ray Hicks of Beech Mountain was renowned for his Jack Tales, told in liars’ competitions on the Blue Ridge in North Carolina. Ray had part-Cherokee ancestry, and both his traditions use the epithet ‘liar’ to describe a storyteller. The Cherokee say ‘Gagoga’, ‘he or she is lying’. This is not lying as we know it, but the tradition of tall-tale telling, the art of keeping an audience believing you are telling a truth for as long as possible. In Wales, ‘Chwedleua’ means gossip as well as storytelling, and this mischievous tradition was embodied in the Welsh language tales of Eirwyn Jones Pontshan, who told of his surreptitious affair with a princess on a train in Pencader Tunnel. And there were the Pembrokeshire English tales of Shemi Wâd Abergwaun, who was carried across the ocean by seagulls to Central Park in New York, only to discover they had deceived him and dropped him in Dublin.

There are animal fables, ‘crittur’ stories, from what the Ohio storyteller Lyn Ford refers to as the Affrilachian tradition. Here are rabbit, bear, fox, possum, skunk, snake and turtle, stories from enslaved people with links to Cherokee and Muscogee that came to me through Uncle Remus. And there are the Welsh animal fables of Cattwg the Wise, about mole, lark, owl, eagle, magpie, cuckoo and a whole host of anthropomorphic animals written by the legendary Iolo Morganwg. Storyteller Phil Okwedy is currently exploring migration narratives from his own Welsh Nigerian traditions, while in New Zealand, Tony Hopkins is telling stories to explore his identity as a Black Cherokee.

My cousin emigrated to Appalachia in the early 1960s. She was studying Homer at University College London when she met an American civil engineer with a penchant for covered bridges, and they moved to work in the old Welsh settlement city of Morgantown, West Virginia, where they put down roots and raised a family. So I fell in love with the folk cultures of both Appalachia and Wales, two sisters who explore the world together, with baking soda in their backpacks just in case.

Baking soda was a cure-all on both sides of the water. My mother made me drink it when I had belly ache, she spooned it into every cake she baked and rubbed it into cut knees, and boy did it hurt. The granny women of Appalachia swore by it, too, as did the herbalist Clarence ‘Catfish’ Gray of Jackson County, West Virginia, who ladled it into his potions and tinctures. The grannies called it ‘Sodey’.

When I was little, I had a die-cast metal Corgi Batmobile from the outrageously camp Batman television series, and it was the coolest car in the world. It was made in the Mettoy factory, which opened in Swansea in 1954, the year that Under Milk Wood was published posthumously after Dylan Thomas’s death in New York. I grew up thinking Batman was Welsh, and Gotham City was Swansea.

You could also buy cap guns, cowboy hats and Indian headdresses from the toy shops, join the I Spy club – which featured a man in an Indian headdress as its symbol – and there were books about conservation of the Canadian beaver, written by ‘Grey Owl’, who wore feathers in his hair, but was really Archibald Stansfield Belaney, from Hastings in Sussex.

Amidst all the phoney appropriation, there was Buffy Sainte-Marie, born Canadian Cree and brought up in Massachusetts. She is a singer and pacifist who pre-dated the hippie movement, was blacklisted by radio stations, became an inspiration to Joni Mitchell, created and financed a literacy scheme for native American children, and wrote the song, ‘Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee’. Buffy told a different story, another history, a bitter truth that was never taught at my schools. This was an awakening from innocence.

The stories here tell of the past and present migrations of people between and within Wales and America. There are no ends or beginnings, no comforting morals, no boundary walls, and certainly no happy ever afters. They are snapshots of easily forgotten lives, a photographic album full of yellow-stained sepia images in a chronological jumble all of their own. These are folk histories, stories of people with confused identities, who developed roots in more than one culture. I am not Aniyunwiya or Appalachian or Affrilachian, but their stories are intertwined with the folk history of Wales, tales of grannies and grandchildren with mixed blood. For each of us has our own individual Mabinogi.

Though perhaps it’s best not to think about it too much, or the little people won’t come again.

And that ain’t no lie.

1

Wolf-Girl Visits Wales

Cherokee elders tell how some of the old ones could change into animals: bears, bison, owls, wolves, coyotes, ravens, jackrabbits, eagles, hawks and frogs. This sounds exciting if you’re into Gothic fiction and graphic novels, and you like the idea of shapeshifting superheroes, or enjoy the darkness of fairy tales. But what if you were told these stories as a child, and all your friends heard them, and they happened in the remote place where you lived, and there were noises at night that terrified you, and the old granny who lived nearby told you they were true?

We lived near one of these elders, and one day while me and my six sisters were playing stickball, a dog came up and joined us. It was just a mutt, with one brown ear and one white, and a patch around its eye. Father found us and asked where we’d gotten that dog from, and we said we didn’t know, but could we keep it. Father said he would see, maybe if it was still around in the morning.

Next morning the dog had gone, but that evening it returned, and every evening, till Father said he would find out if it belonged to anyone. He asked around, but no one had lost a dog, so we kept it. And each evening we played games, we threw rolled up socks for it to fetch, we put our arms round its neck and tried to wrastle it to the ground, and we hunted jackrabbits for it to eat.

Then the dog got a bit frisky. It bit my hand and drew blood, and when I kicked it off, it chased Father’s chickens, and he said if this didn’t stop it would have to go. And we knew what he meant. You know. Bang!

Well, us children didn’t want to lose our dog. We tried to train it, but it still chased the chickens, so we caught it and took it inside and tied it to our old iron bedstead with bailer twine and told it to hush.

In the night there was a howling and a hollering, and Father came in and the dog said, ‘Let me go before the morning.’ But Father knew the stories about the elders changing into animals, and he wanted to see who the dog really was, so he left it tied to the bed. In the morning we found an old woman curled up on the floor at the bottom of the bed, and we recognised her as the old granny woman who lived nearby. He released her and off she scurried. A week later, the old granny was dead as a squashed skunk in the middle of the road.

The elders told Father he had a lucky escape. Old Granny was a cannibal who ate the youngest and weakest in the family, and she turned herself into a dog so she could play with the children and work out who to eat next. And that would have been me. I’m the youngest in the family, so if Father hadn’t spotted her trick, I wouldn’t be here to tell you the story.

Well, after that we upped and left. Father, and all of us seven girls. His grandad was a miner from Romania, and his granny a Welsh seamstress, so that was that, we came to Wales. We settled in a cottage high up in the Black Mountains, and the locals stared at us, ’cos we looked different to them and spoke a language they didn’t understand. They had never heard Tsalagi before, and probably had no idea where Appalachia was, and thought we were the fairies. We weren’t afraid of them. They were likely more frightened of us, especially as we all had pointy hairy ears. We left them alone, and moved around by night, like cats and owls. And howling was heard coming from the woods.

We kept sheep and goats, rabbits and chickens, and Father made sure the farm buildings were in good repair. The farmers left us alone, though they thought it was odd that we never took our animals to market. Truth was we needed all that meat for ourselves. Word went round our more superstitious neighbours that we were descendants of humans who had bred with wolves. Lycanthropes, that’s the word. Soon we were blamed for every sheep that died, every cow that refused to give milk, every crack of a twig in the woods at night, and every nightmare of every child.

After a flock of sheep were found with their throats cut, the air turned black with anger. Father said it was time to move on again.

One night, by the dim light of the crescent moon, my family left, in a single line, carrying all their belongings on their backs, wrapped in shawls and woollen blankets.

The farm became unmanageable and soon fell into disrepair. The corn refused to ripen, the hay crop was poor, and folk believed that the wolfman and his family continued to haunt their old homestead long after it fell into ruins.

The wolf family had fled the country and settled in Cluj in Transylvania, where Father had relatives. They spawned a thousand and one stories and inspired countless writers and artists, not one of whom acknowledged that we had come there from Cherokee via Wales. As they grew, my sisters spread out across Europe, living hidden lives, relying on friends to supply them with haunches of meat, much to the pleasure of the local abattoirs, and the displeasure of parents who feared for their children.

Let me tell you a tale that my Father told me.

A man was waiting at a Welsh railway station when he fell into conversation with a tall man in a trenchcoat and a trilby hat. The man told the stranger that he had come home to help his father manage the farm. One morning, they found all the sheep with their throats cut. There were wolf tracks in the snow, and as they followed, the prints became human. His father’s face turned white as the very snow, and he told his son that this was the work of his own elder brother, the boy’s uncle, who was born with pointy ears, slanting green eyes, and forefingers longer than his middle finger. Years ago his brother had left the farm, angry at receiving no inheritance, and now he had returned for revenge. So the farmer told his son to go before he was killed, and here he was, catching the train to leave Wales for America to start a new life, before his pointy-eared uncle caught up with him. And he stared into the stranger’s shaded eyes beneath the brim of his hat, and asked if he believed the story. The stranger said yes, of course he believed him, and removed his hat to reveal long pointy ears, slanting green eyes and a forefinger longer than his middle finger. Just like U‘tlûñ′ta, Spearfinger, the Cherokee witch who stabbed her sharp forefingers into children and tore out their livers.

And I ain’t gonna tell you what happened next, ’cos it was real messy. You can imagine. But the man never caught the train. And I still have nightmares about meeting Spearfinger.

Back in Breconshire and over the border in Radnorshire, reports of sheep carcasses plagued the local farms. An incomer’s pet wolfhound was suspected, along with a black panther that had escaped from a travelling menagerie, and a coven of local witches who were accused of unspeakable pagan rites under cover of darkness. The truth was more obvious, especially if you were brought up in the company of wolves and vampire slayers.

It was me. Me, the youngest of the wolfman’s daughters. I came to Wales from the Cherokee Nation, but I didn’t flee to Romania with the rest of my family. I stayed on the farm. I knew all about the stories of how the youngest of seven children could be eaten by a witch dog. But I’m a dark girl, and I argued and fought with my father when he told me we were leaving. I spat on the floorboards and said we had already left one homeland, and I was not going to be chased away a second time by no man. I’d been bitten by that old granny witch when I was little, and I knew what I had become.

After my father and six sisters left, I slept alone in the hay bales in the barn, avoiding the farmhouse for fear the neighbours would come for me. I prowled the hedges for beetles to eat, scavenged leftovers from dustbins, took carcasses from gin traps, stole cooling food from windowsills, and hunted for rabbits. But I couldn’t resist the sheep. They were so easy. Trapped by the fences and hedges that were there to protect them, they couldn’t escape my sharp teeth. And I smelled the neighbours approaching long before they suspected I was there. They never saw me clinging to the rafters in the barn.

At night, lying in the hay with warm blood in my belly, I told myself the stories Father had told me. This one he called The White Wolf.

An old man had three sons and a daughter, and he was cruel to them. His wife had died, and he took out his loneliness on his children, screaming at them, beating and abusing them. His daughter knew that something was wrong with her father, and she protected her brothers, wrapping them in warm blankets and covering their ears when the old man came home at night with too much liquor in his blood. And since the death of his wife, people in the town had been found murdered and mutilated, and they feared being out in the dark alone. One night when the old man went out, his daughter took his gun and followed him. Through dark streets she traced his footsteps, until she came to a quiet alleyway full of garbage bins and washing lines. She watched as her father turned into a great white wolf, and the ghost of a young woman appeared and kissed the old man, and his daughter knew this was her dead mother. The white wolf and the ghost lady prowled the streets, and their daughter followed, silently and stealthily. She watched as they approached a small untidy boy, a guttersnipe, a street urchin, and she saw her parents were about to attack, and she knew enough was enough. She took her father’s gun, touched the trigger with her finger, and shot the white wolf through the heart. Her mother vanished, and oh how their daughter cried for her lost parents.

Time passed, more years than could be lived in a single lifetime. I became wrinkled on the inside but still freckled on the outside. A field full of mutilated sheep was discovered near Pontrhydfendigaid, and dog prints were found nearby. There were more sheep attacks, and sightings of wild cats, or hideous half-creatures with slavering tongues that were believed to be breeding in the area, skulking silently along the hedgerows, remaining largely unseen, until they pounced. The newspapers called it ‘The Beast of Bont’. It was time I laid low for a while and found another food supply.

One evening I was prowling along the shelves at the Co-op in Aberystwyth, and was about to slip a leg of frozen lamb inside my parka, when I sensed I was being watched. It wasn’t the CCTV. I was so quick they never captured more than a blur. Only once did a security guard see me, but I disappeared before he blinked, and he concluded I was his imagination. But this was different. I could smell someone. Behind me. I turned and came face to face with one of those young men who have the look of a sensitive poet. Curly hair, hooded blue eyes, you know the sort. He knew I was stealing, and I knew he would say nothing. We met eye to eye. He smiled. This was totally awkward.

I took him by the hand and whisked him out of the shop. All the security man saw on his screen was a young man scurrying away on his own, and he made a mental note of face and clothes for next time. I dragged the young man to an organic vegan cafe where I often passed the days, dreaming of gnawing on the customers’ arms, and enjoying their ignorance of a carnivore in their midst. He threw questions at me: where was I from, was I living on the street, why was I shoplifting? And why didn’t I eat or drink anything when I was clearly hungry? I cocked my head to one side and asked him about his strange accent. He told me he was from the far North. Pen Llŷn. Aberdaron.

I was leaning towards him now, staring into his eyes. I remembered another of my father’s stories, told by his grandfather’s friend, Anthony Booth, a Romanian from Cluj, who had emigrated to work in the mines in West Virginia.

A young affluent couple called Erich and Lorraine Meštrović lived in a fine house on the outskirts of the city. One night, they threw a party and all was well until a blood-curdling scream shook the air and a young man was found outside lying in a pool of blood by the fishpond. The flesh had been flayed from his body and one arm chewed in two. Everyone agreed it was the attack of a wild animal. Next night Lorraine went out into the garden for some air, and Erich heard her shriek. She had found another dead man and had seen a creature running away, dressed as an old woman. Suspicion fell on an old witch who lived nearby, so the villagers marched to her house, burned it to the ground, and chased her out of town. But there were more killings, one on the Meštrovićs’ patio, and now the whole town was consumed with fear. Then one night Erich saw a beast dressed in a young woman’s clothes attacking a man. He took his gun and as his finger closed on the trigger, he realised the woman’s clothes looked familiar. A shot rang out and there was a howl. He ran to see if the man was still alive, and he found, lying on the ground with a bullet hole in her forehead, Lorraine Meštrović.