Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

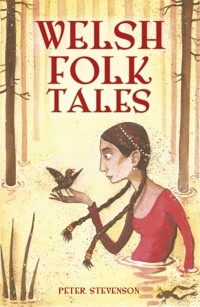

This book, a selection of folk tales, true tales, tall tales, myths, gossip, legends and memories, celebrates and honours unique Welsh stories. Some are well known, others from forgotten manuscripts or out-of-print volumes, and some are contemporary oral tales. They reflect the diverse tradition of storytelling, and the many meanings of 'chwedlau'. If someone says, 'Chwedl Cymraeg?' they are asking, 'Do you speak Welsh?' and 'Do you tell a tale in Welsh?' Here is the root of storytelling, or 'chwedleua', in Wales. It is part of conversation. This book, one to linger over and to treasure, keeps these ancient tales alive by retelling them for a new audience.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 356

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Mae hi’n bwrw hen wragedd a ffyn.

(It’s raining old ladies with sticks)

Diolch o galon

Three songbirds who trod these paths before:

Maria Jane Williams, Glynneath;

Marie Trevelyan, Llantwit Major;

Myra Evans, Ceinewydd.

For my son, Tom, and my mam and dad, Edna and Steve

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

© Peter Stevenson, 2017

The right of Peter Stevenson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8190 3

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction; Chwedlau

1. BRANWEN, RED AND WHITE BOOKS

Charlotte and The Mabinogion

Branwen Ferch Llŷr

2. LADIES, LAKES AND LOOKING GLASSES

The Lady of Llyn y Fan Fach

The Lady of Llyn y Forwyn

The Fairy Cattle of Llyn Barfog

The Red-Haired Lady of Llyn Eiddwen

Dreams and Memories

3. SUBMERGED CITIES, LOST WORLDS AND UTOPIAS

Plant Rhys Ddwfn

The Ghost Island

The Curse of the Verry Volk

The Reservoir Builders

The Lost Land below Wylfa Nuclear Power Station

4. MERMAIDS, FISHERMEN AND SELKIES

Mermaids

The Llanina Mermaid

Another Llanina Mermaid

More Llanina Mermaids

The Fisherman and the Seal

5. CONJURERS, CHARMERS AND CURSERS

The Dyn Hysbys

The Conjurer of Cwrt-y-Cadno

Silver John the Bonesetter

The Cancer Curers of Cardigan

Old Gruff

6. HAGS, HARES AND DOLLS

Witchery

The Llanddona Witches

Dark Anna’s Doll

Hunting the Hare

The Witch of Death

7. DREAMS, MEMORIES AND THE OTHERWORLD

The Story of Guto Bach

The Fairies of Pen Llŷn

Gower Power

The Curse of Pantanas

Crossing the Boundary

8. GOBLINS, BOGEYS AND PWCAS

The Ellyll

The Pwca of the Trwyn

Red Cap Otter

Sigl-di-gwt

9. BIRTHS, CHANGELINGS AND EGGSHELLS

Taliesin

The Llanfabon Changeling

The Eggshell Dinner

The Hiring Fair

The Baby Farmer

10. DEATH, SIN-EATERS AND VAMPIRES

Poor Polly

Welsh Wake Amusements

The Fasting Girls

Evan Bach Meets Death

Modryb Nan

Sin-Eaters

Vampires

The Zombie Welshman

11. CHAPEL, CHURCH AND DEVIL

The Devil’s Bridge

Huw Llwyd’s Pulpit

The Church that was a Mosque

The Chapel

12. SHEEPDOGS, GREYHOUNDS AND A GIANT CAT

As Sorry as the Man Who Killed his Greyhound

A Fairy Dog

A Gruesome Tail

Cath Palug

The Sheepdog

13. HORSES, FAIRY CATTLE AND AN ENCHANTED PIG

The Ychen Bannog

The Ox of Eynonsford Farm

Ceffyl Dŵr

The Horse that Dropped Gold

The King’s Secret

The Undertaker’s Horse

The Boar Hunt

14. EAGLES, OWLS AND SEAGULLS

The King of the Birds

The Ancient Animals

Shemi Wâd and the Seagulls

Iolo’s Fables

15. DRAGONS, HAIRY THINGS AND AN ELEPHANT

The Red and White Dragons

Serpents, Carrogs, Vipers and Gwibers

The Welsh Yeti

The Wiston Basilisk

Shaggy Elephant Tales

16. SAINTS, WISHES AND CURSING WELLS

The Shee Well that Ran Away

St Dwynwen

Dwynwen’s Well

St Melangell

St Eilian’s Cursing Well

17. GIANTS, BEARDS AND CANNIBALS

Cynog and the Cewri

The Man with Green Weeds in His Hair

The King of the Beards

The One-Eyed Giant of Rhymney

18. MINERS, COAL AND A RAT

The Coal Giant

Dic Penderyn

The Treorchy Leadbelly

The Rat with False Teeth

Siôn y Gof

The Hole

The Penrhyn Strike

The Wolf

19. HOMES, FARMS AND MICE

The Lady of Ogmore

The House with the Front Door at the Back

The Cow on the Roof

Manawydan Hangs a Mouse

The Muck Heap

20. COURTSHIP, LOVE AND MARRIAGE

The Maid of Cefn Ydfa

Rhys and Meinir

The Odd Couple

The Wish

21. FIDDLERS, HARPERS AND PIPERS

The Gypsy Fiddler

Ffarwel Ned Puw

Dic the Fiddler

Morgan the Harper

The Harpers of Bala

22. ROMANI, DANCERS AND CINDER-GIRL

Black Ellen

Cinder-Girl

The Dancing Girl from Prestatyn

Fallen Snow

23. SETTLERS, TRAVELLERS AND TOURISTS

Madoc and the Moon-Eyed People

Wil Cefn Goch

Malacara

The Texan Cattle Farmer

24. TRAINS, TRAMPS AND ROADS

The Old Man of Pencader

The Tales of Thomas Phillips, Stationmaster

The Wily Old Welshman

Dic Aberdaron

Sarn Elen

25. STONES, CAVES AND FERNS

The Giantess’s Apron-Full

The Stonewaller

The Scarecrow

Owain Lawgoch

Aladdin’s Cave, Aberystwyth

The Ferny Man

26. DENTISTS, COCKLE WOMEN AND ONION MEN

Don’t Buy a Woodcock by its Beak

Wil the Mill

The Penclawdd Cockle Women

Sioni Onions

The Hangman who Hanged Himself

27. SEA, SMUGGLERS AND SEVENTH WAVES

The Ring in the Fish

Jemima Fawr and the Black Legion

Walter and the Wreckers

Potato Jones

The Kings of Bardsey

28. ROGUES, TRICKSTERS AND FOLK HEROES

Myra, Rebecca and the Mari Lwyd

Twm Siôn Cati

The Red Bandits of Dinas Mawddwy

Murray the Hump

The Man who Never Was

29. SWANS, WOLVES AND TRANSFORMATIONS

Cadwaladr and the Goat

Swan Ladies

Snake-Women

Frog Woman and Toad Man

Werewolves and Wolf-Girl

30. BLODEUWEDD, FLOWER AND OWL

References

Diolch o Galon

INTRODUCTION; CHWEDLAU

There is a Welsh word, ‘Chwedlau’, which means myths, legends, folk tales and fables, and also sayings, speech, chat and gossip. If someone says, ‘chwedl Cymraeg?’, they are asking, ‘Do you speak Welsh?’ and ‘Do you tell a tale in Welsh?’ Here is the root of storytelling, or ‘chwedleua’, in Wales. It is part of conversation.

The writer Alwyn D. Rees explains that when you meet someone in the street, you don’t ask how they are, you tell them a story, and they will tell you one in return. Only after three days do you earn the right to ask, ‘How are you?’

One afternoon, I was talking to a friend in a shop when a ‘storiwr’ spotted us through the window, did a double take, came in, and without pausing for breath, began. ‘You know my next door neighbour? Miserable old boy, never had a good word for anyone, how his wife put up with him. Well …’ Twenty minutes passed. He finished his tall tale, said, ‘There we are’, and left the shop. He had spotted a performance space and an audience, and he had a story stirring in his mind. There was no way of telling whether it was true or invented, and its likely he didn’t know either. This happens all the time in the west. Takes forever to do your shopping.

The Welsh story writer, quarryman and curate, Owen Wynne-Jones, known as Glasynys, told of a tradition of storytelling when he was a child in Rhostryfan in Snowdonia in the 1830s, and of his mother telling fairy tales in front of the fire. Sixty years later, the writer Kate Roberts, from nearby Rhosgadfan, thought Glasynys’s recollection might well have been true of the people in the big houses, but there was no tradition of telling fairy tales amongst the cottagers. She added:

But there was a tradition of story-telling in spite of that, quarrymen going to each other’s houses in the winter evenings, popping in uninvited, and without exception there was story-telling. But these were just amusing stories, a kind of anecdote, and fellow quarrymen describing their escapades … the skill was to make these amusing stories seem significant. I remember literary judgements being passed by the hearth in my old home: if anyone laughed at the end of his own story, or if he told the story portentously and nothing happened in it. Indeed, the way we listened to story-tellers like that was enough to make them stop half way, if they had enough sense to notice. But anyway, the tradition … could have come indirectly to the quarrymen of my district, because many of them originated from Llŷn, where I believe traditional story-telling took place.

Pen Llŷn was renowned for its storytellers. They were farmers, poets, sea captains, garage mechanics, artists, mothers, quarry workers, crafts folk, preachers and teachers, and they moved effortlessly between gossip, fairy tale, politics, songs and criticism. Their fuel was humour.

They would tell you, ‘When the gorse is in bloom, it is kissing time’. There are three species of gorse, their flowering times overlap, so it’s always kissing time in Wales. When the pair of ceramic dogs in the window faced away from each other, it was a message from the lady of the house to the gentlemen of the village that her husband was away. And the tylwyth teg, the ‘fair folk’, were everywhere, small and otherworldly, tall and human, inhabiting the margins of our dreamworld, that space between awake and asleep, where time passes in the blink of a crow’s eye or freezes in an endless fatal heartbeat. Elis Bach lived at Nant Gwrtheyrn in the mid-1800s, and frightened anyone who met him. He was a farmer, a dwarf, a mother’s son, and everyone agreed he was ‘tylwyth teg’.

The storytellers spoke for their communities. Eirwyn Jones worked in a carpenter’s shop in Talgarreg, and was known after his home village, ‘Pontshan’. His stories were often scurrilous and hilarious. ‘Gwell llaeth Cymru, na chwrw Lloegr,’ he said, ‘Better Welsh milk than English beer’. He once walked to an Eisteddfod in Pwllheli where he and a friend slept the night on a rowing boat in the harbour, only to find the morning tide had washed them out to sea. There they stayed, telling tales to the mackerel, till the tide flowed in again. At least he had time to wash his socks. ‘Hyfryd iawn,’ he said, ‘very lovely’.

Old Shemi Wâd sat outside the Rose & Crown in Goodwick spinning yarns to the children about how the seagulls had carried him over the sea to America.

Twm o’r Nant from Denbigh travelled from village to village performing ‘interludes’ from the back of his cart. Myra Evans collected fairy tales and gossip from her family and neighbours in Ceinewydd, filled sketchbooks with drawings of local characters, and documented a way of life rooted in ‘chwedlau’.

In lime-washed farmhouses in the hills, conjurers recited charms from spell books and kept potions in misty brown bottles. Harpers disappeared into swamps, dreamers vanished into holes in the ground, drowned sailors called to long-lost lovers and castles were preserved as bees in amber. Stories, history and dreams entwined as memory.

Into this land came travelling people. The Romani arrived in the mid-1700s, with tales of Cinder-girl and Fallen Snow, ladies darker by far than Cinderella and Snow White. Somali sailors came to work in Cardiff docks in the 1800s and stayed, saying, ‘A person who has not travelled does not have eyes’. Refugees fled Poland after the Second World War and settled on Penrhos Airfield near Pwllheli, where their families still live in ‘the Polish Village’. The Cornish traded with Gower and worked in the lead mines, Italian POWs became farmhands and married local girls, and Breton men cycled the lanes selling onions. All the while, the Welsh emigrated, fleeing poverty and loss of land, becoming miners and missionaries, searching for new hope in the Americas, Australia and Asia. Their stories travelled with them. There are echoes of old Shemi’s tall tales in the Appalachian Liar’s Competitions. Honest, there are.

No amount of caravan sites, bypasses and barbed-wire fences can hide an ancient enchanted land with tales to tell. Standing stones double as gateposts. A Lady of the Lake lives beneath a pond in the midst of a Merthyr council estate. An old church in Ynys Môn was converted into a mosque that now overlooks a nuclear power station. Wind farms have grown amongst the ruins of peat cutters’ cottages on Mynydd Bach. You can trampoline in the depths of a disused slate mine in Snowdonia. Red kites wheel in the air over the National Library of Wales where twenty years ago they were near extinct. Trees once pulled their roots from the ground and marched into battle, where spruce and fir now grow. And a woman was conjured out of flowers to satisfy the whims of a man.

Kate Roberts said, ‘I’m a thin-skinned woman, easily hurt, and by nature a terrible pacifist. My bristles are raised at once against anything I consider an injustice, be it against an individual or a society or a nation. Indeed, I’d like to have some great stage to stand on, facing Pumlumon, to be able to shout against every injustice.’

Storytelling has always offered an ear to those who feel their voices are lost in the wind, or caught in an electronic spider’s web. It draws upon an archive of folk tales, memories of times of upheaval, personal philosophies, revolutionary ideals and the comfort that we are not alone in our dreams. Storytelling is the theatre of the unheard.

There is an old story of a Welshman who was bursting with a secret, so he told it to the reeds that grew by a pond. A piper cut the reeds to make a pipe, and when he blew, he played the secret for everyone to hear. You could whisper a message to a songbird, who would fly to your lover and sing to them of your heart’s desires. The lakes and streams are looking glasses into this world. There are no secrets here. Listen. You will hear stories. Hush, now.

1

BRANWEN, RED AND WHITE BOOKS

Charlotte and The Mabinogion

Around 1350, the ‘White Book of Rhydderch’ was thought to have been copied out by five monks at Ystrad Fflur in Ceredigion for the library of Rhydderch ab Ieuan Llwyd, a literary patron from Llangeitho. A few years later, Hywel Fychan fab Hywel Goch of Buellt wrote out the ‘Red Book of Hergest’ for Hopcyn ap Tomas ab Einion of Ystradforgan. These two books contain the earliest versions of ‘Y Pedair Cainc Y Mabinogi [the Four Branches of the Mabinogi]’, the ancient myths and legends of Wales. They are written in an old form of Welsh, and lay largely unknown to the wider world until William Owen Pughe translated the story of Pwyll into English in 1795 under the title, The Mabinogion, or Juvenile Amusements, being Ancient Welsh Romances, while leaving out the sexual shenanigans. In 1828, the Irish antiquarian Thomas Crofton Croker published Pughe’s translation of Branwen, which caught the attention of the sixteen-year-old daughter of the Ninth Earl of Lindsey.

Charlotte Bertie was a free-thinker, a rebel and a Chartist, who disapproved of her aristocratic parents’ politics. Aged twenty-one, she married John Guest, manager of Dowlais Ironworks, and moved from Lincolnshire to Wales. On her husband’s death she took over as manager, created a cradle-to-grave education system, built progressive schools, supported Turkish refugees, learned Persian and Welsh, brought up ten children and read them fairy tales. When Pughe died in 1835, she completed his translations of the Red and White Books into English, and published them three years later as The Mabinogion.

Within Guest’s book are the Four Branches of the Mabinogi. They have a narrative structure very different to literature, a sense of tales for telling. They sketch only the bare bones of characters, moving through time and space as if they were mist, and make little attempt to be moralising or didactic. They are tales of the tribe, snapshots of moments of upheaval in the history of the land.

The first branch tells of friendships and relationships, the meeting of Pwyll and Rhiannon, and the birth of Pryderi, the only character to feature in all four branches. The second concerns the avoidance and aftermath of war between Bendigeidfran of Wales and Matholwch of Ireland, and Branwen’s doomed arranged marriage. The third tells of the human cost of immigration, settlers and craftsmen forced to move on, and Manawydan’s frustrated attempts to hang a mouse who has stolen his corn. The fourth describes the pain of desire, the rape of Goewin, Arianrhod’s virgin births, her sibling rivalry with Gwydion, and the objectification of Blodeuwedd.

Guest’s politics influenced her passion for the female characters, and through her translation the myth of Branwen became known far beyond Wales.

Branwen Ferch Llŷr

Bendigeidfran fab Llŷr, the giant King of the Island of the Mighty, sat by the sea at Harlech in Ardudwy, with his brother Manawydan and his two half-brothers, Nysien, who could make peace between two armies, and Efnysien, who could cause war between two brothers.

Bendigeidfran saw thirteen ships approaching from the south of Ireland, sailing swiftly with the wind behind them, flying pennants of silk brocade. One ship drew ahead, a shield raised with its tip pointing upwards as a sign of peace. A voice cried out, ‘Lord, this is Matholwch, King of Ireland, seeking to unite his land with yours by taking your sister Branwen ferch Llŷr, one of the Three Chief Maidens of the Island of the Mighty, as his wife.’

A council was held at Aberffraw. Great tents were erected, for Bendigeidfran was far too big to fit in a house, and a feast was prepared. Bendigeidfran sat in the middle, Matholwch next to him and Branwen by his side. They ate and drank, and when everyone thought it would be better to sleep than feast, they slept. That night Branwen slept with Matholwch.

Efnysien had not been told of his sister Branwen’s marriage, and he was furious. He went to the stables and took hold of Matholwch’s horses, cut off their lips to the teeth, their ears flush to their heads, their tails down to their crops, and where he could get hold of their eyelids he cut them to the bone. He maimed those horses till they were worthless. When news reached Matholwch, he was insulted and humiliated, and prepared his ships to sail. Bendigeidfran sent a messenger to explain that he had known nothing of this and he offered gifts as compensation, a new horse for every one maimed, a gold plate as wide as his face, and a silver staff as thick as his little finger and as tall as himself.

Matholwch returned to Bendigeidfran’s court. A council was held, tents were erected, and they feasted, though Matholwch’s conversation seemed touched with sadness. Bendigeidfran offered him another gift, a Pair Dadeni, a Cauldron of Rebirth, saying, ‘If one of your men is killed in battle, throw him in the cauldron and the following day he will be alive, though unable to speak’.

Matholwch asked where the cauldron came from. Bendigeidfran explained it had been given to him by an Irishman, Llasar Llais Gyfnewid. Matholwch knew Llasar. ‘I was hunting in Ireland, when this huge red-haired man walked out of a lake with a cauldron strapped to his back. A woman and children followed him, and if he was big, well, she was enormous, as if she was about to give birth to a baby the size of an armed warrior. They stayed at my court, grumbled about everything, and upset everyone. After four months, my people told me to get rid of them, or else they would get rid of me. So I employed every blacksmith in Ireland to build a hall of iron and fill it with charcoal and beer. Llasar and his family followed the smell of the beer. Once they were inside, I locked the door, set fire to the charcoal, and the blacksmiths blew on the bellows till the house was white hot. Llasar drank all the beer, punched a hole through the molten wall and they escaped, taking the cauldron with them.’

After a night of singing and feasting, Matholwch set sail in thirteen ships for home, taking Branwen and the cauldron with him. In Ireland, Branwen was embraced and offered brooches, rings and jewels. In nine months she gave birth to a son, Gwern, who was taken from his mother and given to foster parents, the finest in Ireland for rearing warriors.

When Matholwch’s people learned of the cruelty inflicted on his horses, they mocked him, and he knew he would get no peace until he took revenge on the Welsh. So he threw Branwen from his bed, sent her to work in the kitchens, and ordered the butcher to slap her face each day with his bloodied hands. For three years, her only conversation was with a starling who sang to her from the kitchen windowsill. She poured out her heart and wrote a letter to her brother Bendigeidfran telling him of her woes, tied it to the bird’s wing and sent it flying towards Wales.

The starling found Bendigeidfran at Caer Saint in Arfon. It sat on his shoulders, ruffled its feathers, and sang. When Bendigeidfran heard of his sister’s punishment, he called a council of the warriors of the Island of the Mighty. They came from all one hundred and fifty-four regions, and after feasting, they set sail in ships bound for Ireland. Bendigeidfran, with his harpers at his shoulders, waded through the water, for the sea was not deep and only the width of two rivers, the Lli and Archan.

The Kings of Ireland’s pig-keepers watched this strange sight approaching over the horizon. They told Matholwch they had seen a mountain covered in trees, with a high ridge and a lake on either side, and the mountain was moving.

‘Lady, what is this?’ asked Matholwch.

‘I am no Lady,’ said Branwen, ‘but these are the men of the Island of the Mighty. They have heard of my punishment.’

‘What are the trees?’

‘Masts of ships.’

‘What is the mountain?’

‘My brother Bendigeidfran, wading through the shallows, for no ship is big enough to hold him.’

‘And the ridge and the lake?’

‘The ridge is his nose and the lakes are his eyes.’

Matholwch and the warriors of Ireland retreated over the Shannon, and burned the bridge behind them. When Bendigeidfran and his army reached this strange river, he made a bridge with his own body and his warriors crossed over.

Matholwch sent a messenger to Bendigeidfran offering compensation for Branwen’s punishment. He offered to make her son, Gwern, King of Ireland. Branwen advised Bendigeidfran to accept, for she had no wish to see her two countries ravaged by war. A council was held, Matholwch built a house bigger than a tent, big enough to hold Bendigeidfran and the men of the Island of the Mighty, and peace broke out.

But the Irish played a trick. They hammered long nails into every one of the hundred pillars that held up the house, hung a skin bag, a belly, on every nail, and in every belly they hid an armed warrior, two hundred in all. Efnysien entered the house, smelled the air and looked around with eyes blazing. He asked what was in the bellies, and was told, ‘Flour, friend’. He prodded the ‘flour’ until he felt a warrior’s head, and he squeezed it until his fingers cracked the skull into the man’s brains. He placed his hand on another belly, asked what was inside, and the answer came, ‘Flour, friend’. Efnysien squeezed every bag until there was not a man alive. Then he sang in praise of himself.

Matholwch entered the house, seated himself opposite the men of the Island of the Mighty, and crowned Gwern King of Ireland. Bendigeidfran called the boy to him and mussed his hair, then passed him to Manawydan, until everyone had fussed him. All except Efnysien. Bendigeidfran told the boy to go to his uncle, but Gwern took one look at Efnysien and refused. Efnysien cursed, stood up, took hold of the boy by his feet, and hurled him head first into the fire. Branwen saw her child being burned alive, and leapt towards the fire, but Bendigeidfran held her between his shield and shoulder. All the warriors rose to their feet, drew their weapons, and there was a most terrible slaughter.

The hall was strewn with the bodies of the Irish dead. They were stripped to the waist and tossed into the Pair Dadeni until the cauldron overflowed. The following morning they crawled out alive, scarred and mute. Soon the hall was strewn with the corpses of the men of the Island of the Mighty. Efnysien saw that he had caused this, and would be shamed if he were not to save his comrades. So he buried himself with the Irish dead, was stripped to the waist, and thrown into the cauldron. He stretched himself across the rim, and pushed until the cauldron shattered into four pieces. Efnysien’s heart shattered too, but his redemption spurred the men of the Island of the Mighty to victory, if victory it was.

Bendigeidfran was wounded in the foot with a poisoned spear, and only Branwen and seven men escaped, Pryderi, Manawydan, Glifiau, Taliesin, Ynog, Gruddieu and Heilyn. Bendigeidfran ordered his men, ‘Cut off my head, take it to the White Hill in London, and bury it facing France. But first, go to Harlech and feast for seven years. The birds of Rhiannon will sing to you, and my head will keep you entertained as if I was alive. Then go to Gwales in Pembrokeshire, and look towards Aber Henfelen in Cornwall. Stay for eighty years, I will be with you, then open the door, and bury my weary head in London.’

So the seven men cut off Bendigeidfran’s head, and sailed with Branwen to the Island of the Mighty. They rested at Aber Alaw on Ynys Môn, and Branwen turned and looked back at Ireland, and cursed the day she had been born. ‘These two good islands destroyed because of me,’ and her heart broke in two, and she was buried there, in a four-sided grave on the banks of the Alaw.

And the Second Branch of Y Mabinogi nears an end.

2

LADIES, LAKES AND LOOKING GLASSES

The Lady of Llyn y Fan Fach

On the Black Mountain lived a dreamer, a poet and a romantic named Rhiwallon, whose job was to look after his mother’s cows. One day, he saw a herd of small milk-white cattle grazing on the meadowsweet that grew round the edge of Llyn y Fan Fach, and standing in the water was a girl, plaiting her red hair. He felt an urge to give her a gift, but all he had was his lunch. So he offered her some stale bread. She took one look at the bread, grinned like a Cheshire cat, told him he’d have to try a lot harder than that, rounded up her cows and vanished beneath the water.

Rhiwallon was entranced. He decided to impress her with softer bread, so he asked his mother for some unbaked dough, and he sat by the lake and waited. The milk-white cattle appeared, followed by the girl, who was nibbling watercress. He offered her the dough, it squelched between her fingers. She stared at him, shook her red head, laughed like a donkey and vanished, cows and all.

Rhiwallon was entirely enchanted. All he needed was bread that was neither hard nor soft, and she would be his. His mother made him some lightly baked muffins and he sat by the lake and waited. When she appeared he offered her a muffin, which she sniffed, nibbled a little and then gobbled it down. He begged her to be his wife. She looked bemused, wiped the crumbs from her mouth, pulled the pondweed from her hair, and said if she ever received three unfortunate blows in any way other than love, she would leave him forever. He said he would rather sever his hand than strike her, so the marriage was agreed.

She brought a dowry of milk-white cattle, and counted them out of the water in the old way: ‘un, dau, tri, pedwar, pump’, remove a stone from one pocket and place it in another, ‘un, dau, tri, pedwar, pump’, over and over.

Time passed. She raised three fine sons, and taught them about the medicinal properties of water and the curative nature of herbs. But she rarely smiled and never laughed; there was a melancholy in her.

At a christening, she told the mother that the child would die before his fifth birthday. Rhiwallon gripped her arm and told her not to be so miserable, for this was a celebration. She freed herself and told him that was the first unfortunate blow.

At a wedding, she burst into tears, for she thought the couple were doomed to unhappiness. Rhiwallon held her by the shoulders and told her this was a time to smile. That was the second unfortunate blow.

At a funeral, she burst out laughing, for her friend was now free of worldly cares. Rhiwallon pushed her out of the church and told her to pull herself together. The third, and final, unfortunate blow.

She whistled her cattle, the brindled, bold-freckled, spotted, white-speckled, four mottled, the old white faced, the grey Geigen, the white bull, the little black calf suspended on the hook. They followed her over Mynydd Myddfai, even the slaughtered little black calf came alive and galloped after them, and they all leapt into Llyn y Fan Fach and vanished.

Rhiwallon raised his three sons alone, and they grew into fine young men. One day their mother appeared, and told them they were to use their knowledge of herbs and water to care for others. They developed cures for aches and pains, charms for melancholy and miseries, potions for gloom and despondency, and they became the most famous healers in Wales – the Three Physicians of Myddfai.

But they never cured their mother, for there was nothing wrong with her.

The Lady of Llyn y Forwyn

A farmer from Ferndale fell in love with a young woman who lived beneath Llyn y Forwyn, where she tended her herd of milk-white cattle. He courted her, they were married and lived happily at Rhondda Fechan, and each morning she was heard singing to her cows. A girl at Ysgol Llyn y Forwyn, when asked if she knew the story, said, ‘Yeah, saw her this mornin’ on me way to school. She was singin’.’ The lake is now surrounded by a housing estate, and a wooden statue of the lady was charred by fire a few years ago, when arson was popular with the valley boys.

The Fairy Cattle of Llyn Barfog

One morning in late summer, a cattle farmer from Cwm Dyffryn Gwyn was standing on the hill above Llyn Barfog when he saw a gwraig annwn, a lady of the Otherworld. She was dressed in green, with ivy and holly berries in her hair, and rouge smeared on her lips. She was tending a herd of small milk-white cattle who were grazing on the meadowsweet that grew by the side of the lake. The farmer desired one of these milk-whites, so he caught a small one and tethered it in his farmyard. He barely noticed the lady.

The little cow was eager to please, and gave the finest, foamiest, frothiest milk, cream and cheese. She flirted with the Welsh Blacks and soon the farmer had the sturdiest herd of breeding cattle, and he became the richest man in Meirionnydd. But his wealth drove him mad. As the fairy cow grew old, instead of putting her out to pasture, he fattened her for slaughter. Killing Day came and the butcher raised his knife. There was a shriek and the butcher’s arm froze in mid-air. The lady appeared from the lake, dripping with slime and pondweed, and whistled for her little cow to come home.

The cow ran to her mistress, leapt into Llyn Barfog, and where she touched the water, a white water lily grew. All her children, Welsh Blacks and milk-whites alike, followed their mother into the depths and soon the whole lake was covered in white water lilies, as it is to this very day.

And the rich farmer was a poorer man for the rest of his days.

The Red-Haired Lady of Llyn Eiddwen

There I was, sat drawing by Llyn Eiddwen on Mynydd Bach, when a farmer with short bottle-red hair, a ruddy outdoor face, big smile and an even bigger baggy multi-coloured jumper and little black leggings, sat down next to me, and asked, ‘What you doin’, love?’ and offered me a fairy cake.

Now, I had been warned not to speak to any strange red-haired women on Mynydd Bach, as one is known to live in the lake where she tends her herd of snow-white cattle who paddle in the shallows at dusk. The lake was the site of rave parties in the late 1800s when a wealthy young man, Mark Tredwell, built a castle on the island, and kept a private army of boys mounted on Shetland ponies. In 1819, Augustus Brackenbury, a gentleman from Lincolnshire, bought the commons around Llyn Eiddwen to build another castle. The boys of Trefenter, thinking Brackenbury had no right to buy the commonly owned land where they dug their peat, dressed themselves as women and demolished the castle in one night. The battle over land rights and enclosures lasted ten years, and is known as the War of the Little Englishman.

Another Lady lived just down the valley in Llyn Fanod, and a beautiful creature once walked out of nearby Llyn Farch, only to be shot for the pot by a local farmer. There were more Ladies at Llyn Syfaddan, Llyn y Morwynion, Felin Wern Millpond, Llyn Du’r Ardu, Llyn Dwythwch, Llyn Corwrion, Llyn Coch, the Pool of Avarice at Twmbarlwm, the Taff Whirlpool, and more. They are voices from the past, visible in the reflections in the water, memories of those who lived there before valleys flooded.

I told these stories to the red-haired farmer and asked if she had ever seen the red-haired Lady of the Lake. She bellowed with laughter, and said that no lady could ever live in Llyn Eiddwen. ‘It’s full of leeches. She’d be eaten alive.’ Then she told me tales of encounters she had when she was a girl with the tylwyth teg, corpse candles, and fairy funerals. And off she went down the lane, singing.

Well, I reckon I met the red-haired lady that day. And I have a stale fairy cake to prove it.

Dreams and Memories

A young servant from Nannau was in love with the dairymaid at Dol-y-Clochydd. One dark night, he was on his way to propose to her when he fell into Llyn Cynwch near Dolgellau and sank to the bottom. He found himself in a beautiful garden full of flowers and herbs that surrounded a marble palace. He knocked on the door and was greeted by the King of the Fairies. The King recognised him as a lost lover, so he led the servant along a tunnel to a slate door. The servant stepped through the door and found himself in the kitchen at Dol-y-clochydd, where the dairymaid was sat by the hearth weeping because her lover had been missing for months and she thought him drowned. They embraced, she kissed him on the lips, and the King closed the door.

In 1936, the writer T.P. Ellis, who told this story, wrote, ‘I asked one of the shareholders of the local water company if he knew what was at the bottom of Llyn Cynwch, and with a brain-wave of super-realistic rationalism, he said, “Yes, mud”.’

3

SUBMERGED CITIES, LOST WORLDS AND UTOPIAS

Plant Rhys Ddwfn

In Cardigan Bay, between Pen Llŷn and Pembroke, was once a fabled land of forests and villages. The people were fair and handsome, though small. They cared for the land as if it was their own, but never once believed they owned it. They planted forests where they hunted and foraged, and always left offerings in exchange for anything they took. This was the land of Plant Rhys Ddwfn, the Children of Rhys the Deep – not deep below the sea, Rhys was a thinker, a philosopher. He planted herbs that hid his land from the prying eyes of the mainlanders. Only if you stood on the one small clump of this herb that grew on the mainland would you see Rhys’s world, and if you stepped away you would forget how to see it again. No one on the mainland knew where this piece of turf grew, so no one saw Rhys’ land. All they saw was rain.

The Rhysians had children, their numbers grew, they built more homes, and soon there was barely enough land to grow food. The mainlanders heard the distant rumble of empty bellies, although they mistook it for the anger of the Gods. The Rhysians took to crafts, they became quilt makers, wood carvers, and iron smelters, famed for their black cauldrons. They traded by sea like the Phoenicians before them, and visited the markets of Ceredigion where they traded their goods for corn. As soon as they were seen at the markets, prices went up. The poor folk of the mainland said the Rhysians were friends of Siôn Phil Hywel the farmer, but not friends of Dafydd the labourer.

They traded with a man named Gruffydd ap Einion, as his corn was fresh and his prices fair. Gruffydd was a libertarian, a free-thinker, intrigued by the stories of their idyllic life. As years passed, the Rhysians honoured Gruffydd by taking him to the clump of herbs, and in that moment he saw all the knowledge and wisdom in the world, kept safely in forests and books. Preachers and politicians were few. Sheep were plentiful. Choughs wheeled and kestrels hung in the air. The land was rich beyond dreams. It was the Utopia he had dreamed of.

Gruffydd asked how they kept themselves safe from crime, and they told him that Rhys’s herbs hid them behind a veil of watery mist and the rain kept the mainlanders away. Rhys had rid their world of those who lived only for personal gain in the same way St Patrick had ejected snakes from Ireland. The only memory they had was a curious drawing of a creature with horns, a bosom of snakes, the legs of an ass, holding a great knife, with bodies lying all around. No one wished to meet that creature.

When Gruffydd stepped away from the patch of herbs, he forgot how to see the land of Plant Rhys Ddwfn, though he still had his memory and dreams. The Rhysians never forgot their friend and traded with him all his life, until one day they came to the market to find Gruffydd had passed over to the Otherworld and the traders had increased their prices. The Rhysians walked away and never returned.

The land of Rhys the Deep, the Welsh Utopia, is still there, glimpsed from the window of the train as it trundles past Cors Fochno, hidden behind sea defences designed to prevent flooding, heard in the ringing of the bells of Aberdyfi, written in the storybooks about Cantre’r Gwaelod, the Welsh Atlantis. The sea keeps no secrets.

Oh, and Plant Rhys Ddwfn, in West Wales, is a colloquial name for those who lived here before, the marginalised, the dispossessed, the fairies.

The Ghost Island

Gruffydd ap Einion was visiting St David’s churchyard when he looked out to sea and saw a ghost island. Before he could reach his boat, the island vanished. An old woman who lived on the mountainside told him he had found the herb that allowed him to see the land of Plant Rhys Ddwfn. The next day he went to the churchyard, and as soon as he saw the island, he dug up the herb with a ball of soil round its roots, and placed it in his boat. With the island visible, he rowed towards it, and landed in a cove where he was welcomed by Rhys. He visited every evening until, one day, he never returned. Everyone agreed he had gone to live with the fairies, where he belonged.

The writer Jan Morris saw Rhys’s land from the doorstep of Llanon Post Office. As a child, I saw it from the shoulder of Yr Eifl on Pen Llŷn.

I still see it. No matter where I stand.

The Curse of the Verry Volk

The Norman Lord of Pennard Castle on Gower was celebrating his daughter’s marriage with feasting and orgy, when a guard reported seeing strange lights in the woods. The Lord, fearing the Welsh were attacking, gathered his soldiers and went to investigate. In a clearing, they found the Verry Volk, dancing in celebration of the marriage. The drunken Lord, thinking he was being mocked, ordered his soldiers to charge. The slaughter was unexpected and terrible. Standing amidst the carved bodies of her dancers, the Verry Queen pointed at the Lord and called him, ‘Coward’. She cursed him for his cruelty and stupidity, wailed into the wind, and vanished.

The following day the wind blew and the sea stirred, and sand poured over the land. For hours the storm screamed, until the castle and its people drowned in sand.

A wailing was heard in the wind, which was said to be a gwrach-y-rhibyn, a death witch, although a golf course has been built next to the castle’s remains so the wailing is more likely to be a frustrated golfer trying to chip out of a bunker.

The old town of Kenfig was also submerged by a sandstorm after the indulgences of the Normans; excessive feasting and indulgent orgies accounted for the flooding of old Tregaron which lies beneath Maes Llyn. Tegid’s palace is at the bottom of Bala Lake; Llys Helig was flooded by the sea off the Great Orme; King Benlli’s court was swallowed by Llynclys; and it is still a mystery how old Swansea came to disappear below Crumlyn Lake.

The Reservoir Builders

In 1881, work began constructing a dam across the Vyrnwy Valley to create an artificial lake to supply Liverpool with clean drinking water. The village of Llanwddyn was evacuated and demolished, and more than four hundred people were moved to a new village built by Liverpool Corporation further down the valley. Even the ancestors in the churchyard were exhumed and reburied. The dignitaries of the Vyrnwy Water Works Project were so pleased with their dam they erected a public monument to themselves.