Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The coastline of Ireland, from the rugged fjords of the west to the steely waters of the north, is infused with memories of loss, sadness and beauty. In this work, maritime historian and author Pat Nolan speaks to the fishermen, boatbuilders and sailors whose lives have been shaped by these seas. What emerges is a picture of a way of life that has changed dramatically in recent years, and yet retains a consistency as timeless as the returning tide.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 209

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

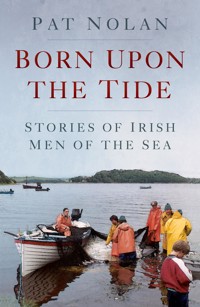

Front cover image: Landing the catch at Inver Strand. (George Gallagher)Back cover: Celtic Explorer on the high seas.

First published 2017

The History Press Ireland

50 City Quay

Dublin 2

Ireland

www.thehistorypress.ie

The History Press Ireland is a member of Publishing Ireland, the Irish book publisher’s association.

© Pat Nolan, 2017

The right of Pat Nolan to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8571 0

Typesetting by Geethik Technologies, origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by TJ International

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. A Gamut of SeagoingJim Moore of Portavogie, County Down

2. Accountancy Not For PeterPeter Campbell of Skerries, County Dublin

3. One Hundred Years of ServicePaddy Hodgins of Clogherhead, County Louth

4. Carrick-a-Rede Salmon FisheryAcki Colgan of Ballintoy, County Antrim

5. Steadfast in his BeliefsArthur Reynolds of Dún Laoghaire/Bergen

6. Spent a Lifetime FishingSeamus Corr of Skerries, County Dublin

7. A Man For All SeasonsGeorge Gallagher of Inver, County Donegal

8. Resolute BeliefsBrian Crummy of Dún Laoghaire/Dunmore East

9. Born in a LighthouseTed Sweeney of Blacksod/Belmullet, County Mayo

10. Died Just Over a Year AgoMarion, Andy and John of North Donegal

11. Kerry Blood in their VeinsPat Moore of Killybegs, County Donegal

12. Wouldn’t Change a ThingMichael O’Driscoll of Schull, County Cork

13. Throw Him Out!John Francis Brosnan of Dingle, County Kerry

14. Reflections of an OctogenarianFrank Kiernan of Kinsale, County Cork

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION

This book was born out of my interest in recording the experiences of men who have been to sea. If left undocumented, such experiences – ways of life really – will quickly fade into oblivion. My motivation is to help keep the memory of such ways of life alive.

Born Upon the Tide reflects the variety of experiences – opinions, memories, humorous incidences and occasional disasters – as recalled by the men I met on my travels around the coastline of Ireland.

While the book focuses on the lives and times of commercial fishermen, there is also substantial space given to men with deep-sea and related shore-work experience. Irrespective of vocation, all the men who have contributed to this book have an intimate knowledge of the sea and the often tough life that goes with it.

1

A GAMUT OF SEAGOING

Jim Moore of Portavogie, County Down

It had been fifty odd years since I last travelled along the splendid scenic coastal route of the Ards Peninsula in County Down. During the course of a recent telephone conversation with Portavogie native, Captain Jim Moore, I gathered that many changes had taken place in the interim. When I asked the good captain if it might be possible to have a chat with him regarding his lifetime experiences, the response was, ‘No problem, I will be delighted to meet you, and by the way, Jim is the name.’ A date was arranged there and then!

On arrival at Portavogie I drove towards the pier. What I saw before me bore no resemblance to what had existed all those years ago. I spoke to a gentleman out walking a dog and raised the subject of how the pier had changed since I’d last seen it. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘there have been two major developments in that time, one in the 1970s and another in the 1980s. The actual size of the pier has been doubled and a completely new structural arrangement was put in place in order to improve shelter facilities. A slipway has also been incorporated and the basin has been deepened. As you can see, there is also a large marketing hall/area and an ice-making machine. It is very different indeed.’ Berthed at the pier, in addition to a number of smaller boats, there were upwards of twenty large trawlers (70–80ft), the vast majority of which were timber-hulled and of Scottish origin.

Jim’s bungalow was easy to find and the man himself answered the door and warmly welcomed me to Portavogie. Comfortably seated inside and with the small talk over, Jim began to relate his memories.

I was born on 18 January 1933. My parents were local and my father was a fisherman. While attending the Public Elementary School from the age of 10 years onwards, all boys were gearing up for the only career on offer – fishing! That was it, no other career was ever considered. That being so, when I left school in 1947 I went straight into my father’s fishing vessel as a crewman. The exact date was 26 July 1947.

Jim Moore at his Portavogie home.

We fished for hake off the Isle of Man and landed our catch nightly at Peel. As the year moved on we went into the Clyde and fished out of Campbeltown and Girvan. Coming up to Christmas we moved to Ardglass; a very busy port in those days. Boats and men from the north-east Scottish ports of Peterhead, Fraserburgh, Macduff, Buckie, Hopeman and Lossiemouth came in great numbers. Among them came the men who are reputed to have introduced seine netting to the north of Ireland in 1934 – brothers Willie and Jimmy, members of a famous Thomson fishing family.

In addition to the Scotch boats, you also had the Mourne men coming from Kilkeel and Annalong. Yes, Ardglass was indeed a very busy port in those days. To add to the confusion, it was necessary to land catches by 6pm so that buyers could get their purchases transported in time to catch the Belfast to Heysham Ferry. Whiting was the predominant catch landed; anything else was mere by-catch.

Jim remained in that particular fishing scene for three and a half years. During that time he was in daily contact with men who had returned from having done stints on merchant ships. Men tended to join the Merchant Navy whenever fishing was poor. It was a practice akin to that carried out by migrant workers. After their overseas travels, the men spoke glowingly of the wonderful places they had been to the marvels they had seen, and generally eulogised about the continuous sunshine and blue skies of faraway places. Furthermore, whilst out fishing, whenever a merchant ship passed by, not only were the old hands able to name the ship’s owner, they also knew where it was coming from and where it was going to. As time passed, Jim was influenced by what he heard and decided to personally experience life on the high seas.

In January 1951 he joined a Burns & Laird Line (B&L) ferry ship running between Belfast and Glasgow. It was a fairly short-lived job as the ageing ship was broken up a year later. Jim stayed on with the B&L Line for a period of time during which he did relief work. Next he moved on to permanent employment with the Kinsale Head Line, a shipping company that worked out of Belfast and ran ships to Baltic Sea ports. Then aged around 19, Jim has fond memories of those days. He recalls the ship taking on coal at a port on the east coast of Scotland for transportation to Danish destinations such as Korsor and Copenhagen. Having unloaded the coal, the next assignment was to sail further on up the Baltic Sea, occasionally to its extremity, and take on timber at Swedish and Finnish ports for transportation back to Belfast and Dublin. For a moment he reflected before saying, ‘To me, Denmark was and still is a wonderful country.’

Not one to stand still, a year or so after joining B&L, Jim moved on to an Ellermen Papayanni Line ship, the 5,000-ton Maltasian, engaged in running general cargo, and occasionally full loads of potatoes when in season, to Mediterranean Sea ports. Having discharged the cargo, it was usual to take on oranges and other fruits for shipping back to the UK. However, one trip was to be very different. Before leaving London, orders were received to take on a cargo of timber for the UK at a Black Sea port. The cargo was in fact to be taken on at Constanza, Romania, which was then behind the Iron Curtain. Jim reminded me:

It was 1954 and the Cold War between the USA and the Soviet Union was at its coolest. There were all sorts of stories told about how foreign sailors who stepped out of line in Soviet-controlled countries were harshly dealt with. Nevertheless, with all its intrigue, uncertainties and dangers the crew were looking forward to the adventure.

Having discharged the last part of its outbound cargo in Salonika, Greece, the Maltasian set sail for Constanza, via Istanbul and Zonguldak, a small port on the north coast of Turkey. Jim continued:

As we approached the Romanian coast, Russia’s centuries-old punishment of sending undesirables to Siberia for the most trivial of offences was very much on our minds. No one wanted to spend the remainder of their days in those infamous ‘salt mines’. Around 5 p.m. we dropped anchor. Immediately customs and port officials boarded. The crew were mustered and all accommodation was thoroughly searched. A medical examination, including checking for venereal diseases, was carried out by a doctor. The ship was cleared to berth at midnight. We spent the following ten days loading timber – the only western nation ship at the port. Thirty-six hours’ notice was required of crew members who wished to go ashore. Intense security and strict regulations were in operation at all times. I recall that we were in Constanza on the day in 1954 when, against the odds, West Germany won the World Cup by defeating the highly fancied and crack Hungarian team of that era by a scoreline of 3-2. Sailing away from the port we had the same number of crew members as when we arrived. Things turned out not to be as bad as they had been painted. It was an experience that will stay with me for the rest of my life; all the memories are still fresh in my mind.

Following what Jim describes as, ‘A wonderful time on the beautiful Ellermen Papayanni Line ship’, he joined the Canadian Pacific Railway Line, a company that then ran a passenger service from Liverpool to Montreal or, in the wintertime, to Halifax or St John’s when the St Lawrence River froze over. The line also ran twenty-day West Indies cruises from New York during the winter months. He went on to say how fortunate he was to have worked on two magnificent ships on those trips. He served as quartermaster on the Empress of Australia and as an able seaman (AB) on the Empress of Scotland. In those days, going ashore in Cuba was a formality and Havana was, he says, ‘A beautiful city’.

While life was good, the years were passing by and Jim had an unfulfilled ambition – he wanted to become an officer. To facilitate that aspiration, he took a relief job in one of the John Kelly (Belfast) ships trading around the British Isles. In that way he had an opportunity to study and, as time went on, to chop and change between shipping companies where he gained the necessary experience to further his cause. Over a period of nine years between 1956 and 1965, he worked for and achieved Certificates of Competency at all levels – Mates Certificate (1956), Masters Home Trade Certificate (1960), 2nd Mates Foreign Going (1962), and the ultimate Masters Foreign Going Certificate (1965). Along the way he married Cissie in 1962.

Having acquired his qualifications, Captain James Moore returned to sea. He went to a Glasgow company, Gem Line, better known as Robertsons of Glasgow. He had previously worked with the Gem Line company during the period of ‘experience gaining’ for his Masters Foreign Going Certificate of Competency.

However, now he had a young family growing up at home who, on his return from long trips, were beginning to ask their mother, ‘Who is that man?’ Yes, home life was more or less non-existent! Jim, who was by then 34 years of age, and Cissie sat down to discuss what was best for the future. The conclusion reached was that it would not be right for him to go on spending so much time away from home. But what was he to do between then and retirement age – thirty years hence! Inevitably, a return to fishing came up as an option. The arguments made in favour of fishing pointed towards the fact that good money was being made at the time, he had been a fisherman in the past, many of his mates were fishermen, and he knew everyone involved. Why not give it a go! He would purchase his own boat. Should things not work out for whatever reason, he had the qualifications to go back to sea at any time. Although it was a major step, Jim and Cissie decided to follow their instincts. He retired from the merchant shipping way of life in October 1967.

Five months later, on 23 March 1968, Jim purchased a boat that was at that time fishing out of Ayr. She was named Kincora, a 70ft Tyrrell-built Lossiemouth boat, owned by Jimmy Thomson. Quoting Jim, ‘I had the Kincora for the next fourteen years; it was one of the happiest and prosperous periods of my life.’

By 1982 the Kincora had over thirty years of service behind her and was at a stage where she was beginning to need a lot of maintenance. Therefore Jim decided to sell her. A replacement came in the form of the Killybegs-based, Norwegian-built Sanpaulin, owned by the legendary fisherman, Tommy Watson. Her stay under Jim’s stewardship was relatively short – a couple of years or so – mainly because she had deep draft, which did not suit Portavogie harbour.

The next boat to come under his ownership was the Mayflower, a 66ft Lossiemouth vessel, built at the Herd and Mackenzie Yard in 1957. He bought her on 6 June 1984. When it came to re-registering the boat, the date of purchase corresponded with D-Day (6 June 1944) so he used the digits ‘44’, i.e. ‘B44’. Jim had a long association with her as she remained in the family for twenty-four years. When he retired as skipper on 11 November 1994, his son Ashley, who now works for the Belfast Harbour Board, took over. By then the boat was getting old and the decision was made to sell her. So ended Jim’s direct involvement with fishing, but he is still able to recall how the fishing scene in the north-east port of Portavogie unfolded over a period of many years.

The Mayflower with the McCammon Rocks (Portavogie) off the port stern quarter.

When I asked Jim to tell me a little of the changes that had taken place, this is what he had to say:

During the 1930s the main types of fishing here were herring drifting and anchor seining. After the Second World War ring-netting came in, a lot of which was carried out by local boats in the Clyde. Circa 1955 trawling began to emerge as the foremost method of fishing. While it became well established during the 1960s, with prawns being an important part of the catch, a few ringers continued to work out of here. From the early to mid-1970s, influenced by Scotch and Isle of Man fishermen, queen scallop/queenie dredging became significant. From around 1976 onwards there was a decline in demand for queenies, resulting in a drop on prices paid. Consequently some boats returned to trawling. Prawns and whitefish, including whiting, cod, and hake to a lesser extent, became the main catch. For the most part, fishing was virtually non-existent during the month of May – often referred to as ‘hungry May’: when boats underwent annual overhaul and cleanup. In late May and early June, herring began to show up. While not yet plentiful, prices were good. Towards the end of June or early July, they arrived in copious amounts and continued as such until well into September. As time went on, big boats with powerful engines did really well at the herring. Come October it was back to trawling.

As with all County Down fishing fleets, a great deal of their time was spent harvesting the waters away from home, with the Isle of Man sea area, the Solway Firth, the Galloway coast and Firth of Clyde being most frequented. On a personal level, Jim concentrated a great deal on queenie dredging. He found it to be very profitable fishing. There was, he said:

Big fishing and for the most part prices were good at around £5 per bag. A normal catch for two days was around 100 bags. We landed at Peel when fishing off the Isle of Man. It was a case of two days at sea, a night in Peel, and back out the next day. When fishing further south and closer to the mainland we occasionally landed to a Scottish merchant at Garston, a port on the Mersey. We also queenie fished in Cardigan Bay. It used to take us fifteen hours from Portavogie harbour to the fishing grounds. We left home on Monday, made two landings at Holyhead, and returned home on Friday. The dredges we used were made in Peel and required quite a bit of maintenance.

As for the development of fishing on the County Down coast, especially the move away from drift netting to seining, Jim believes much is owed to the Scotsmen who came to Ardglass. They were, he said, ‘miles ahead of us’. He attributes the progressiveness of the Scots to the fact that their boats tended to be new and were equipped with top-class fishing gear. Those who owned the boats were frequently wealthy professionals and businessmen who had no direct link with fishing, but who had lots of money to invest where it mattered most, in providing the best of boats and gear. It was a major advantage to have an experienced, well-informed and open-minded skipper, who might also be a shareholder. It was also claimed that a famous net-making firm at Elgin, close to Lossiemouth on the Moray Firth, worked very closely with local fishermen, to the extent of putting nets into boats and monitoring effectiveness. As a result of consultation between skipper and net maker, alterations were made to enhance performance. It is said that legendary fisherman Willie Thomson, who went on to become a prolific whiting catcher, and indeed was decorated by King George VI for his expertise, benefited greatly from working in such an environment.

In contrast, boats on the County Down coast were likely to be skipper- and/or family-owned, well-used, second-hand Scotch vessels requiring a great deal of costly maintenance. The financial backing prevalent on the Scottish scene was not readily available in County Down. The tendency was to go on doing what had always been done – the same old fishing methods using traditional gear. As such, local men were dependent on their Scotch counterparts to pioneer the way and share in their experience and expertise. The arrival of the Lossiemouth Thompson brothers, Willie and Jimmy, to fish out of Ardglass in the mid-1930s heralded a new era in fishing on the Irish coast. They were the men who had revolutionised fishing off the north-east coast of Scotland, specialising in seine netting for whiting. Quoting Jim:

Being the gentlemen they were, they willing supplied information based on their experiences to advance the cause of their County Down colleagues in every way possible. As a result, standards of fish catching and fish handling improved greatly. Neither did they shy away from pointing out to their fellow skippers that if they were to really advance they needed to invest in bigger, more powerful boats. By the late 1940s around twenty-four boats, many of them Scottish, fished from Portavogie in the wintertime. The use of seine nets ensured that very large landings of whiting were recorded. As time went by and the Thompsons of Lossiemouth moved on to fish the whole Irish coast, the legacy of knowledge on seine net fishing they passed on to local fishermen at many ports left an indelible mark on the development of fishing on this island.

Jim went on to tell me of an earlier Portavogie fishing era. He spoke glowingly of ‘a great relationship’ that built up between Portavogie fishermen and their Kinsale counterparts before the First World War. It was in an era frequently spoken and written about when mackerel drift netting off the south-west coast of Ireland attracted vessels from far and wide. Apparently the Portavogie men greatly looked forward to the annual southward venture. Jim explained:

The boats left here around St Patrick’s Day. All going well they would reach their destination two days later. Occasionally they sheltered in Dún Laoghaire on the way. Once in Kinsale, the boats remained based there until late June when they returned home in time to scrub up and paint for the Twelfth of July celebrations. The fishing grounds stretched westwards from the entrance to Cork harbour to the mouth of the Shannon, with the ports of Baltimore, Valentia [Knightstown] and Fenit further bases for large fleets. Any season a Portavogie crewman earned £25 was considered good; £15 was fair, while £10 was poor. It was not unknown for boats to return home in debt. That’s the way it was! Once the First World War started, German U-boats became very active off the south coast and that really was the beginning of the end for the Kinsale mackerel fishing. That the great Cunard liner Lusitania had the misfortune to fall victim to a German U-boat torpedo attack 11 miles off the Old Head of Kinsale in May 1915 has been well chronicled. By the time the war ended the market for mackerel had collapsed. The young men who went to Kinsale from Portavogie never forgot it; even to their dying days they talked about it. It was the highlight of their lives – the furthest they had travelled, and a definite purple patch. They talked about how nice the people were and importantly that the girls were more beautiful than any others. Yes, it would appear that even the lights shone brighter in Kinsale than anywhere else! Of course they had plenty of time to socialise as in those days they landed fish on Saturday morning and didn’t go back out until Monday night.

As mentioned earlier, the harbour complex at Portavogie bears no resemblance to what I recalled in the early 1960s, so I asked Jim about the transformation that had taken place. His rundown on the developments went back to a time when there wasn’t a harbour or pier at Portavogie. Before 1900 no harbour existed: boats lay inside a nearby rocky ridge, known as McCammon Rocks, which offered reasonably good shelter. Catches of fish were rowed ashore in punts and landed at a spot known as Cully or Mahood’s Gut. (Cully and Mahood were the main fish buyers at the time.) Work commenced in 1900 on the construction of a harbour at the present-day site. It ran into difficulties around 1906, due to lack of funding. However, the project was completed by 1910. In 1917 additional work was carried out, including the provision of a facility whereby logs could be placed across the inside entrance in adverse weather conditions – an arrangement similar to that at Clogherhead Dock.

By the early 1950s the harbour was no longer fit for purpose, due to the fact that the fleet had grown considerably and safety had become a problem. Redevelopment work began in 1952. For a period of three years, the fleet was obliged to use nearby harbours while work was in progress. Improvements made, costing £270,000, included structural work and dredging. Further redevelopments in 1975 and 1985 have resulted in the greatly enlarged and highly impressive harbour complex that incorporates a purpose-built dock and fish market hall. Since 1976 boats land catches directly to the market hall rather than on to the quay, as had previously been the case.

Portavogie Pier, September 2011.

My long, informative and interesting chat with Jim was drawing to a close when he invited me to go and view his collection – of what, I wasn’t sure at the time, but I expected to see a few model boats. He led the way to the attic, where it turned out that the entire space, floor, walls and ceiling, was chock-a-block with an extraordinarily colourful miscellany of model seagoing vessels of all kinds (many of which were made by Jim), photographs, posters, and multiple items of memorabilia, including football club mementos and a host of other knick-knacks. Many of the bits and pieces had been brought from overseas. To say I was flabbergasted is an understatement. It is a truly amazing collection. What a pity a suitable centre can’t be found to publicly display such a fascinating assortment.

What an interesting afternoon I spent at Portavogie with the ever so cordial Captain James Moore!