Botanical Short Stories E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'The stories are all so very different, some of them being quite compelling and tender featuring an interesting variety of voices and nationalities with a wide range of characters and settings' - Advolly Richmond A group of botanists in search of rare species dismiss local custom at their peril. Love in all its wildness and wonder is found clinging to crumbling chalk cliffs and growing through cracks on city streets. A scientist takes a radical step to understand her houseplant. A poet remembers her beloved flowers, and the longing for a magnificent tropical garden outlasts death. From tokens of love to neolithic burial gifts, bridal bouquets to seasonal wreaths and healing potions to artistic masterpieces, flowers and plants have a multitude of meanings and a long and complex relationship with us. They brighten our homes and delight us in garden and countryside, convey our emotions and symbolise the stages of our human lives. Throughout the anthology, interactions with the natural world bring opportunities for new beginnings, transformation, and a chance to heal. This rich and wide-ranging collection celebrates the deep connection that exists between people and plants in fourteen short stories as varied, diverse, and global as the botanical world itself.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 259

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

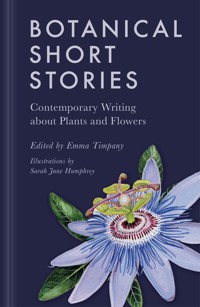

Cover and internal illustrations © Sarah Jane Humphrey, 2024

Sarah Jane Humphrey has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as illustrator of the cover and internal illustrations.

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Selection and Introduction © Emma Timpany, 2024

The right of Emma Timpany to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All content is copyright of the respective authors, 2024

The moral rights of the authors are hereby asserted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 310 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

DEDICATION

My late father, Alister, was a creative man of great talent, compassion, and energy who excelled as a florist, gardener, and designer in his fifty years of life. He loved reading, believed in the transformative power of learning, and wrote compellingly about floristry and design. His loyalty, creativity, and dedication to what he loved continues to inspire me, as does the memory of his life in flowers. This book is for him.

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Acorn Vase – Clare Reddaway

Mercy – Kate Swindlehurst

Flowers – Emma Timpany

The Garden of the Non-Completer Finisher – Angela Sherlock

In Search of Monkey Cups – Hildegard Dumper

Dog Roses – Tamar Hodes

Mulch – Rebecca Ferrier

Breathing Becoming Midori – Aulic Anamika

Narcissus – Maria Donovan

A Clear View – Mark Bowers

Nigella – Thalia Henry

A Homesick Ghost Princess Visits Her Home on a Full Moon Night – Priyanka Sacheti

Emily – Hiding in a Flower – Diana Powell

Stitching for Clem – Elizabeth Gibson

Notes

Acknowledgements

The Contributors

INTRODUCTION

Creating an anthology of botanical short stories is a dream come true for me, as it combines my lifelong love of flowers with my favourite form of fiction, the short story.

Deriving from the Greek anthologia, from anthos (flower) + logia (collection), the word ‘anthology’ could not be more appropriate for a group of stories about lives as varied, diverse, and global as the world of plants itself.

Reflecting the deep relationship between the life cycles of people and plants, this selection explores universal themes such as love, myth, loss, and healing. Wilderness is never far away, as a woman manages to bring a part of her beloved Welsh farm to a new home in the city in Clare Reddaway’s ‘The Acorn Vase’, while in Hildegard Dumper’s ‘In Search of Monkey Cups’, a group of botanists in search of rare species find more than they bargained for in the jungles of Malaysia.

The green world takes a strange and exciting turn in Aulic Anamika’s ‘Breathing Becoming Midori’ as a scientist takes a radical step in order to truly understand the life of her houseplant, while in Rebecca Ferrier’s wonderful story ‘Mulch’, a lonely, green-fingered woman shunned by her community decides to grow her own man.

Wild plants have long provided us with sources of food and medicine, as well as less-benign remedies that may harm rather than heal. This theme is explored in Kate Swindlehurst’s powerful story ‘Mercy’, where a knowledge of traditional plant lore enables a mistreated woman to create a better life for herself in historical Cambridge, while in ‘A Clear View’ by Mark Bowers, a woman foraging chalk cliffs for rock samphire meets a man struggling to survive an upbringing as harsh and unforgiving as the environment of the plant itself.

Elsewhere, the memory of gardens created and flowers cultivated over a lifetime bring comfort to those at the end of their days. In Diana Powell’s deeply felt ‘Emily – Hiding in a Flower’, we lie with the poet Emily Dickinson as she remembers the flowers that formed the heart of her life and work, while Priyanka Sacheti’s story, ‘A Homesick Ghost Princess Visits Her Home on a Full Moon Night’, beautifully imagines love for a flourishing tropical garden continuing after death. Set in a seaside village in southern New Zealand, Thalia Henry’s ‘Nigella’ is a subtle, finely balanced piece about the personal meaning a flower can hold throughout a lifetime.

In the harsh, unrelenting conditions of a Dutch bulb factory, Maria Donovan’s ‘Narcissus’ is a skilful exploration of the industrial cost of beautifying our homes and gardens. Meanwhile, the true spirit of good gardening is put to the test in a quintessential English village in Angela Sherlock’s warm-hearted story, ‘The Garden of the Non-Completer Finisher.’

In my story, ‘Flowers’, the chance to grow flowers in a Cornish field brings two strangers together, allowing them both the opportunity to heal, while love in all its wildness and wonder is to be found in the turbulent relationship between two mismatched lovers in ‘Dog Roses’ by Tamar Hodes. The final piece in this book, Elizabeth Gibson’s ‘Stitching for Clem’, shows a couple weaving a deeply happy world from the small, often overlooked things – companionship, music, sewing, and growing – which deepen the richness, beauty, and meaning of life.

I am immensely grateful to Sarah Jane Humphrey for creating the exquisite artwork in Botanical Short Stories. Sarah is a Royal Horticultural Society gold medal-winning botanical illustrator whose talent and creativity shines brightly. As well as using darkness and light to brilliant effect in four black and white internal illustrations, our cover design features Sarah’s beautiful drawing of a passionflower (Passiflora). The passionflower’s circular structure echoes the shape of our planet Earth as well as symbolising the cycle of life. Its flowing, flexible tendrils enable the plant to climb towards the light, and its petals open to uncover an intricate, complex, and exquisitely formed heart. This species seemed the perfect choice to represent the shared passion for all things botanical and literary you will find within these pages.

Emma Timpany

January 2024

ENGLISH OAK, Quercus robur

THE ACORN VASE

CLARE REDDAWAY

I have to leave. That’s what they tell me. I don’t have a choice.

I found the acorn on the long track that leads from the road to my house. It was paved with white stones once, but now grass runs down the middle and if I’m not careful it grows tall in the summer and brushes the underside of the car. I drive the lawn mower over it when I can be bothered. I don’t mind the grass, but Gareth the postman worries about his van getting damaged. I’ve told him a few fronds of grass won’t harm it, but he doesn’t listen, and I’d like to carry on getting my post even if it is mostly bills.

Alongside one edge of the track is a dry stone wall. It’s still in a good state. Well, I suppose they’re built to last for centuries. I often stand and look at the wall. The slabs are thick and must once have been a uniform grey, but now they are so covered with lichens they resemble a map of the world, but not a world we yet know. One patch forms the white of a frozen continent, another the speckly green of an island. There are splats of ochre and mini forests of ghost grey that sprout in the crevices. I see smears of orange, blotted with spots of black – deserts and cities perhaps. Another lichen is so dark a grey it is almost indistinguishable from the rock itself. Whenever I walk along the track I notice the spread – a new patch of yolk yellow here, a mound of moss there, new lands emerging in front of my eyes.

The acorn fell from the oak trees that hang over the wall. They are sessile oaks, twisted and bent, their branches covered in that same ghost-grey lichen with streaks of deep green moss. The track is littered with acorns in the autumn, but I have never picked one up before. Why would I?

Briony gave me the vase for my birthday. ‘It’s an acorn vase, Mum. You fill it with water and rest an acorn there, in the neck. It’s shaped to hold it.’

A vase for an acorn. Not for a big bunch of daffs, harvested down by the stream, not for an armful of dahlias gathered in the midday sun of a late summer’s day, not for a tiny bunch of snowdrops, picked when you can hardly believe they’ve dared to poke their heads out it is still so chill, offering hope that the wind will drop and the air will warm and there will be blue sky once again. No, none of these, but an acorn.

‘Thank you. How lovely.’

When she’s gone, driving straight off after lunch so she can get to the motorway before darkness falls, when her car has bumped down the track and turned left onto the lane and vanished, I put the vase back in its box and place it high on a bookshelf where I never have to look at it again. This daughter of mine doesn’t know me if she thinks I want to see an acorn in the middle of my breakfast table rather than the bright purple of a crocus or the unfolding petals of my favourite apricot rose.

I love the track. The light there is limpid green, and when the sun shines it slants through the twists of oak with shafts so sharp you could cut yourself on them. Opposite the wall, on the other side of the track, the hill rises. The hill is steep but I walk up it every day, and my feet are sure on the turf path that leads up over a slab stile, up through the bracken and the bramble, up to the close-cropped turf of what was once a fortress. On the flat top, I stand and survey the land laid out below me. The tiny squares of fields, enclosed by walls and hedges. The solitary trees, oak and beech, that look like parsley heads from here. Gareth’s post van, a dot of red crawling along the lanes. Dai Evans’s farm, his cattle sheds grouped around the yard. His herd of Welsh Blacks move from field to field, following the grass. Beyond the pastureland the moors form a protective shield, blue as they meld into the horizon, and there in the far, far distance, is a dark line that I know is the sea.

It is the hill that betrays me.

That day, there is no sun. The wind is from the west, barrelling straight into me like a fist. It takes my hair and whips it across my skin. A sudden shower of rain douses my face and makes me feel tingle-fresh and alive.

But the rain makes the rocks slippery. I often relive what happens next. It plays like a film when I close my eyes.

It is on the way back down that I slip. I place my right foot on a treacherous surface where the lichens and the mosses have turned to slime and it goes out from beneath me. I make a noise, halfway between a shout and a groan, as I crash down onto my back. My head hits a sharp stone and the breath is knocked out of me.

When I can, I breathe in, count to five, exhale. And again, and again like I did when I was in labour. It didn’t work then either. A vision of Briony as a squalling baby floats in front of me. Then I see her running with the boys along the track, racing each other, kicking a ball. They turn into the gate and vanish. As I watch them, the shock recedes.

I sit up. Good. I can manage that. I will be slow, gentle with myself. My head is throbbing from the stone, but that is to be expected. I push myself to standing and there it is: a shooting pain through my ankle when I put my foot to the ground. I test it. I can move my foot, that’s positive, but if I put any weight on it, the pain is too much to bear.

I curse myself for not bringing my walking stick. For not taking more care. For choosing to walk in the rain.

It can’t be helped.

I cannot manage the path on one leg; it is too steep. But I must get down. I have no means of communication. The mobile phone that my children are so keen on was left on the kitchen table. No one passes this way. No one will be here until Gareth, tomorrow morning, and I know that at my age a night on the hillside with no protection will kill me.

I drop to my hands and knees and crawl. What had been a short trek up now seems interminable and it takes an eternity to get back down to the track.

I flop onto the ground at the base of the wall, my wall, to rest.

The house is not far.

The house is so far.

I lean my back against the stone slabs and run my hands over the scrubby grass. It is then that I find the acorn. It is green and luscious, fatter than most of the plants around here which scrabble for water and life in the thin earth. I roll it in my palm. I sniff it. It smells of the earth. I put my tongue out and lick it. It tastes of tree and wood. I put it into my pocket. Steeling myself, I back onto my hands and knees and crawl along the turf to my house, my home.

‘A small fall, nothing serious,’ I tell Jake on the phone. ‘My ankle’s swollen, but I’ve put a bag of frozen peas on it and I’ve got the leg up. I’ll be as right as rain in the morning.’

‘Thank you for ringing,’ I say to Ben. ‘But there’s no need to worry.’

‘I was being careful,’ I tell Briony. ‘Don’t fuss.’

I find it hard to move out of the kitchen. I find it hard to do anything at all. I haven’t taken my coat off. I put my hand in my pocket and I find the acorn. Briony said that it had to be wrapped in a wet cloth to help it germinate. I put it on the table in front of me and I stare at it. It doesn’t move.

I’m lying about the peas and I’m lying about having my foot up. I sleep on the old sofa in the kitchen. In the morning my ankle is like a hot red football.

It is two days before I hobble out to the Land Rover, clamber up behind the wheel and drive, slowly and probably dangerously, to hospital.

‘It’s just a broken ankle!’ I say to Briony. ‘I can manage!’

‘Mum!’ she says, and I can hear the exasperation in her voice. ‘Of course you can’t. I’m coming to get you.’

I should be grateful. I have friends whose children never call. Who visit at Christmas and send a card for birthdays. I have other friends whose children live next door. I’m not sure which is best. What I would like is children who listen. But then maybe I didn’t listen to them.

Her car pulls up outside the house. My home, her home for many years.

‘We need to leave straight away,’ she says as she strides into the kitchen.

I’ve lifted down the acorn vase, taken it out of the box. I’ve read the instructions. I’ve wrapped the acorn in a wet tea towel and it’s sitting beside the vase right in the middle of the table. I think it will please her, and I want to please her. She doesn’t glance at it.

‘Have you got your bag?’

‘I’ve asked Maggie to keep an eye on the sheep and feed the hens,’ I say. ‘She’ll take the eggs of course. I’ve got a couple of boxes for you though.’

She can barely stop herself from rolling her eyes.

‘We’ve got shops you know, Mum,’ she says. ‘And I can’t believe those sheep are still alive. They must be, what, ten years old?’

‘Your father –’

‘Mum, tell me about it in the car. I want to get going before it’s dark. I took a day off work for this.’

She takes my bag and I shuffle after her, awkward on my crutches. I take the big key and lock the back door. I never lock the back door. I pause before I get into her car. The air is silken soft on my cheeks. I can smell wood smoke floating up from the valley. I can see the blue hills in the distance. The oaks are rustling.

Briony revs the car. I climb in. It smells of pine air freshener and the beige interior is spotless.

‘Off we go,’ she says. I can see the muscle in her jaw twitch as she clenches her teeth.

We bought the house on impulse. It was the ’70s; we’d got married in a whirlwind of free love and cheap cider. Soon we had three children under four and were bouncing off the walls of our tiny flat in Kentish Town. Davey was a teacher. I had paused my job as a librarian to look after the children. My hands were red raw with washing nappies, I never got a wink of sleep, and my feet ached from pushing a pram along those hard pavements. One day I saw an ad in the back of The Lady in the doctor’s waiting room: ‘smallholding for sale.’ We took the train to Wales the next weekend and fell in love all over again. A stone house with a small oak wood, eight acres, and a stream of its own, so rundown and remote we could just about afford it. We would keep goats and sheep and pigs, we’d plant vegetables, the children would run wild, and we’d be self-sufficient. This was the era of The Good Life after all.

It was hard work but it was worth it. Well, for us, anyway. I took a few years to get the hang of vegetables, as I’d never so much as planted a seed before. Cabbages, broccoli, potatoes, sweetcorn. Raspberries, strawberries, blackcurrants, gooseberries. We milked the goats and made cheese. We sheared the sheep, learned how to spin wool, knitted socks and hats and gloves. I made jam to sell in the market and the year that Davey had a glut of carrots we were proud to provide stock to the local shop. The children helped: digging and mucking out, collecting eggs, feeding, planting, herding, milking. Of course, as they got older, they became busy with their school work. And they wanted to have their own social lives. There wasn’t much in the way of public transport but Briony still trudged the mile down the track and the lane to catch the one bus to town so she could moon around the shops on a Saturday. We understood.

One by one they left for university, and when they graduated they each went travelling before settling down to jobs. If there was some small part of us that hoped one of them would come back and help turn the farm into a modern, thriving business, we never let them know and none of them suggested it. Ben became an engineer. He works on big infrastructure projects, spends a lot of time in the Middle East. Jake went into the City, became an insurance man, making shedloads of cash. I look at him in his suit and can’t imagine him under a goat, pulling at an udder. Briony is in retail. She’s got three of her own shops now. She tells me that what she sells is called homeware.

Briony’s car swoops through her gate and up to her front door. No grass here. Her drive is immaculate pale gravel with not a weed in sight. Her house is red brick in a street of identical red brick houses. She opens the car door.

‘Here we are!’ she says. ‘Need a hand?’ I manage to swing my legs out and manoeuvre my crutches so that I can stand. I hop up the steps and her husband, Luca, opens the door. Briony follows me with my bag. She leaves the eggs on the back seat.

She shows me into the guest bedroom. It’s on the ground floor and has an en suite bathroom. It is sparkling clean, and when I turn on the tap the water gushes hot. I think briefly of the spartan bathroom at home, the old thin taps crusted with limescale, the bath that takes an age to fill because of low water pressure and ancient pipes.

‘There we are, Mum,’ says Briony. ‘You can pop into bed and have a good rest now. Is it warm enough?’

It’s far warmer than home, where the windows don’t fit and the gap under the door means there’s always a draught. Davey meant to fix it but he never did.

‘I’ll bring you a hot milky drink in a bit. We can have a good chat in the morning. Night, night!’ She leans in to kiss me. It’s 8.30 p.m.

Davey died five years ago now. Heart attack. He lay face down in the bottom field for a couple of hours before I realised I hadn’t seen him or heard him for a while. If only I’d gone with him to put up the fence that morning. If he’d had his mobile phone with him. If he’d gone to feed the pigs first rather than check on the sheep, he might still be alive. I’d been concentrating on a batch of gooseberry jam. I was stirring it when he left the kitchen. I didn’t say goodbye. I think my last words to him were, ‘Don’t bring all that mud in here.’ ‘What if’ and ‘if only’ still go round and round my head but I suppose if it hadn’t been then, it would have been another morning, another afternoon, a different field, a different season, the same outcome, rather like my fall. I miss him.

It is difficult keeping it all going on my own. The list of jobs gets longer and longer. When the children and grandchildren come home they don’t want to spend their weekend mending the shed roof or mucking out the pigs. Slowly, it is all crumbling around me.

I wake up the next day to hear cars drawing up to the house and voices in the kitchen. I wash and dress carefully, make sure that my hair is brushed and smooth, my cardigan clean and the buttons done up correctly. I don’t want to give them an excuse.

There they all are, sitting around the kitchen table. Ben, with his permanent winter tan. Jake, not in a suit because it is a Saturday but he looks so ironed he might as well be, and Briony, shiny and smart as always. Jake springs up to hug me, and Ben pulls out a chair to settle me down. Briony puts some fresh toast and a steaming cup of coffee in front of me.

‘We need to talk,’ she says.

They all look very serious as they outline the problem. I am old. Getting frail. This fall is the first of many to come. I can’t cope on my own.

I protest that I can, that it was Briony who insisted –

But I am overruled.

It is selfish of me to want to carry on living in the house. It is nice enough, but there is always too much to do, far too much for one person. It is too isolated. Too far away. They all have busy lives. Families. Jobs. Social engagements.

I think of my home. The patina of our occupation layered down over the years. The willow tree that we planted by the stream when we first moved in a silvery old lady herself now, dipping her leaves in the water every spring. The pencil marks on the kitchen wall charting the children as they grew, Jake and Ben racing to be the first to get to five foot. The drift of snowdrops under the oak trees, covering the graves of guinea pigs, cats, dogs, and a lone snake, each marked with a solemn wooden cross. The summer house that Davey built so we could sit after we’d finished work and have a glass of wine together, looking out over our land.

‘But you love it too, don’t you? Couldn’t one of you take it on?’ I say. I look around their faces. No one meets my eye.

Briony shows me the prospectus. A neat bungalow, half a mile from her house. It has a garden, compact, flat, easy to manage, all enclosed by a brand new six-foot wooden fence.

‘We can paint the fence, Mum, whatever colour you want,’ she says.

The inside is open plan. A new kitchen. A wet room, whatever that is. A large bedroom with a wardrobe.

‘What can you see when you look out of the window?’ I say.

‘Does it matter?’ says Ben.

I think of the hill, and the land I can see when I stand there, spooling out below me towards the sea. I think of the map of new worlds on my wall.

‘Yes,’ I say.

‘We need to move quickly, Mum,’ says Jake. ‘This is a golden opportunity. These properties don’t often come on the market.’ And I knew that they’d cooked up this plan together.

‘I want the wildness of the moor; I want to feel the wind in my hair!’ I think. But I don’t say it out loud.

Briony drives me home. It is all settled. I will move as soon as I can sell. She drops me off. I stand by the kitchen window.

‘How about your two, Bri? Won’t they miss it?’

‘They really liked this place, Mum, you know they did. But they’re teenagers. They’re all about video games and summer trips to Croatia now.’

‘And you? Do you remember how you’d roll down that slope over there, all of you, racing to the bottom? You’d come in covered in grass seeds, sneezing your heads off. And that year when we got snowed in when you built a whole family of snowmen?’

Briony rattles her keys in her hand.

‘Don’t forget the estate agent’s coming tomorrow to measure up, Mum. Ten o’clock, he said. I’d better be off.’

She gives me a peck on the cheek and is out the door and into the car before I can say anything more.

I look around the kitchen. The Aga, the clutter of jam jars on the shelves, the pine work tops. I see Davey leaning against the sink laughing as he tells me about his day. I see him stamping his feet to get the snow off as he comes through the back door, clapping his hands together to warm himself up. I see the whole family sitting around the table, talking over each other, gesticulating and cackling and giggling. I look at that table and notice a folded cloth, next to the acorn vase. I’d forgotten all about it. I unwrap the cloth, dry now, and there is the acorn. It has split and a thread of white root has pushed itself out. It is the length of two joints of my little finger. I am about to throw it away, then I hesitate. Instead, I fill up the vase and place the acorn in it, the root hanging down into the water. I can almost hear it drinking.

I always thought that they’d take me out of this house feet first in a coffin. I take six of my best glasses out of the cupboard. I throw them one by one against the wall so that they shatter onto the floor. I like the sound of them breaking, but it doesn’t make me feel better. I stare at the heap of broken glass for a minute and then I get the dustpan and brush.

My home doesn’t take long to sell. ‘A desirable property ripe for redevelopment,’ the estate agent says. I stop doing my chores. I don’t care if the fences fall down, or if the currants need picking, or that the stream is blocked so it will flood in the spring. Dai comes with his van to take away my sheep. I give the chickens to Maggie. I walk and walk every day. I go down to the stream and watch where the kingfishers swoop, hoping to see one for the last time. I go up to the hill to stare into the far distance. I run my fingers over the worlds painted on my dry stone wall. I look over into my oak wood. In Scotland they call oaks grief trees. As the wind rustles through their leaves, I can see that they are weeping for me.

In the vase, the acorn is growing. A green bud bursts out of its side and works its way up into the air. It becomes a tiny slender stem, and first one, then two minute oak leaves begin to unfurl.

Briony comes to help me pack up. She is brisk and efficient. She brings cardboard boxes, which she secures with masking tape.

‘We’ll divide things into sell, charity shop, dump, keep,’ she says. ‘I want keep to be the smallest pile!’

We start at the top of the house and work down. We label furniture and pictures, sort through clothes and keepsakes. We are in the kitchen dividing up crockery when she pulls a small plate out of the cupboard. It was her favourite when she was little. It’s got a picture of Eeyore, Pooh, and Piglet setting off on an adventure.

‘I didn’t know you still had this,’ she says. She smiles and then her eyes fill with tears. My tough, practical daughter is crying over a plate.

‘Sorry,’ she says. ‘Silly.’ She blows her nose. I stare at her.

‘It’s not like you to get sentimental,’ I say. She looks at me.

‘I’m just trying to be strong for you, Mum. One of us needs to be. I don’t think you understand. I love this place. I know every stone of it, just like you do! But you can’t stay here anymore!’

‘I want to …’

‘Have I told you about my nightmares, Mum? I get them all the time now. I wake up in the middle of the night screaming because I see you lying at the bottom of the stairs, unable to move, freezing to death, and I’m not there to pick you up. I see you with a broken leg when you’ve fallen down a crevice on one of your precious walks. You’re trapped and in agony. And yes, I see you face down in the bottom field having had a heart attack, and there’s no one to find you because Dad’s already dead!’

Briony is crying properly now, big tears running down her cheeks.

‘I’m terrified for you, Mum. I want to look after you, but I can’t. This place is your dream, yours and Dads, it’s not ours. But that doesn’t mean I don’t care about you!’

I hug her and I sit her down and I make her a cup of tea, stirring in a dollop of honey like I always used to do.

‘I know you love it here. I know that it is breaking your heart to leave. But for us it is you that’s important,’ she says, her eyes fixed on the tea. ‘And maybe you can bring something of here with you.’

She runs her finger down the acorn vase in front of her, and I finally see it as it was meant to be seen. As a way of carrying my present into my future.