Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

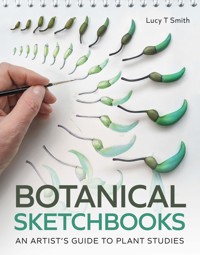

This inspirational guide explains how a botanical sketchbook can take many forms and hold different meanings. It shows how a sketchbook can be used as a workbook to study plants through drawing and painting in a variety of media. It includes examples of preliminary work for finished pieces, experiments in colour and exploration of plant anatomy, and shows how these studies can be made away from the pressure of creating the perfect, polished piece of final botanical artwork. It goes on to feature sketchbooks created for their own sake as a curated space for an artist to draw and record plants over a period of time, or a particular place.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

1Materials

2Methods and Techniques

3Flowers

4Fruits, Pods, Cones and Seeds

5Succulents, Cacti and Other Pot Plants

6Working in the Field

7Capturing Trees Throughout the Seasons

8Scientific Botanical Sketchbook

9How Sketchbook Studies Inform the Finished Work

Index

INTRODUCTION

Structured or organic, neat or messy, each study in my botanical sketchbooks has a unique story and a purpose behind it.

A botanical sketchbook can take many forms and hold different meanings for different people. It is a place where a botanical artist or illustrator studies plants through drawing and painting, capturing them using a variety of media. Whether they are preliminary works for final pieces, experiments in colour, or explorations of plant anatomy, the studies in a sketchbook can be made away from the pressures of achieving the perfection and polish of the finished artwork. But the sketchbook is not only for preliminary and exploratory work; it can also exist for its own sake, as a curated space in which an artist draws and records plants over a period of time, or in a particular place.

My sketchbook practice has evolved over the decades of my career as a professional botanical artist and illustrator. Some of my earliest working drawings were not bound by a book at all, but drawn on loose sheets of paper that were covered in notes and tiny pressed specimens, hastily curated into loose-leaf folders. I eventually became more organised, seeing the benefits of keeping my work in the more ordered space of a bound pad or book. Since then, I have never looked back and I now have a stack of sketchbooks in all shapes and sizes.

My sketchbooks hold drawings in pencil; some are loose and sketchy, others tight and highly detailed. Some show plants drawn quickly in the field or objects at my desk. In contrast, others are covered with the painstakingly detailed results of highly ordered flower dissections executed for scientific illustrations. Whilst pencil work predominates, watercolour also features – and often the two appear together. Pen and ink also make an appearance. It is very satisfying to look at all my sketchbooks produced over the years and see the progression of my skills, the beginnings of ideas for large projects, and the experiments that led to successful finished pieces.

All the examples and projects described here are illustrated either with work taken from sketchbook studies made over the past 30 years of my career as a botanical artist, or with work made specifically for this book. The process of reviewing my archive has proven that even an old hand like me can still be open to new ideas. In creating fresh artwork for the book, I took the time to try out some techniques and approaches that were less familiar to me. I found it all hugely inspiring and hope to incorporate some of them into my art practice in the future. My hope is that this book will do the same for you!

Sketching takes our appreciation of plants to a new level through the observation and depiction of their complex and beautiful forms. There are so many layers to explore and draw: form, structure, pattern and detail.

CHAPTER 1

MATERIALS

Capturing plants in a botanical sketchbook is as much about the process as it is about the end product. Drawing and painting plants brings a joy that comes not only from the artist’s connection with their subjects, but also from the practical, physical and tactile aspects of the materials used to create the work. I have yet to meet an artist of any kind who does not derive great pleasure from their use of art materials. During my career as a botanical artist, I have discovered what works best for me, but I also like to try new things from time to time.

My sketchbooks fall in a number of loose categories. Some are for very specific types of work, while others contain a variety of different approaches. The type of sketchbook I use for scientific drawing may not be suitable for a study that uses watercolour, for example. Some sketchbooks are so beautifully made that I am inspired to fill them with studies that become works of art in their own right, creating a kind of curated piece.

The right tools for the job: enjoying the look, feel and quality of the materials we use to capture our botanical subjects is at least as important as appreciating the plants themselves.

TYPES OF SKETCHBOOK WORK

Before detailing the types of books and materials I like to use, it is useful to categorise the type of work I do in my various sketchbooks. Each type has specific needs, although they do overlap sometimes.

Preparatory Work Sketchbook

This type of sketchbook contains the working drawings for my work as a scientific botanical illustrator and artist. The pages will also be used for notes, ideas and preliminary sketches for figuring out the composition of the final work.

The sketchbooks I have used, both in the past and currently, range in size from A5 to A3. They are bound in different ways and contain many different paper types.

The spiral binding of my scientific illustration sketchbook allows it to be laid flat on a desk or easel – perfect for resting my hand on the page to work on detail. The heavier paper can withstand the repeated erasure needed to get scientific drawings just right. I use this sketchbook in both horizontal and vertical formats.

Spiral-bound R. K. Burt Fabriano 5 watercolour sketchbooks in A5 and A3 sizes. The 300gsm watercolour paper is designed to take wet media without buckling, so I can experiment with techniques such as wet-in-wet watercolour with these autumn leaves.

This small Moleskine sketchbook containing watercolour papers became my sketching and note-taking book for some aspects of the giant Victoria water lily illustration project. As a seed of Victoria amazonica germinated and grew in a fish tank, I recorded the changes each day across two pages.

In this type of sketchbook, there will be many drawings of parts of plants, including dissections. As the work is mostly done in pencil, the book usually contains cartridge paper. I also use this sketchbook when making preparatory drawings for watercolour paintings, especially those of plants with complex forms. Sometimes I add colour to these studies, although the amount of paint that can be applied is limited by the paper type. Ideally, this sketchbook will be made up of a heavy paper (at least 160gsm) with a smooth surface, although it should not be too smooth, as some grain texture is needed for the pencil to grip on to.

When I know that I will need to add a little more watercolour, I will use a sketchbook containing heavyweight, smooth-surfaced watercolour paper. Conveniently, the paper that I use for my final watercolours, Fabriano 5, is available in spiral-bound pads of different sizes. This allows me to test techniques and colour in the sketchbooks, so that I can see exactly how the watercolour paint will work on the paper when I come to create the final version.

I use a larger size of pad or sketchbook for graphite drawings and watercolour studies, and a smaller size for making quick colour notes and colour sketches. The latter is especially useful for studying subjects in situ, as it is the most portable. This paper is suitable for working on in all media but is also quite expensive, so I would not use it for everyday scientific studies.

Explorative Sketchbook

Sometimes, I make sketchbook studies simply for the pleasure of delighting in the drawing process. This type of sketchbook is a place for the activities of observation, drawing and painting for their own sake, and the studies in them may or may not be used as preparatory work for a final piece. There is a wide variety of approaches, from an investigation of form, which may include some dissection, to the documentation of a time and place through plants. Whilst the intention in these books is not to prepare for finished pieces of work, these studies often do result in ideas for projects. As this reflects an open-ended approach, they are my most creative sketchbooks. The paper in these books must be versatile enough to take a variety of media and styles.

Exploring the flowers of Galanthus elwesii from a bee’s viewpoint. As a professional botanical illustrator, many of my sketchbook studies are for specific projects and there is a pressure to draw to rigid guidelines and time frames. In my exploratory sketchbooks, I enjoy taking the time to draw and paint without an agenda. Drawing a snowdrop flower from this angle may be scientifically unconventional but I like the resulting shapes, patterns, and information it provides.

SKETCHBOOKS AND PAPER

Size

Ready-made sketchbooks come in a wide variety of sizes, from small A6 through to larger A3 and above. There are several factors to take into consideration when choosing which size to buy. Do you want a portable sketchbook that fits in a pocket or bag, or will you be working in your sketchbook at a desk or easel? Are you drawing large or small objects? It is a simple matter to choose the most practical format for your needs; in reality, you will probably end up with a range of sketchbooks in different sizes.

My collection of sketchbooks comes in a variety of sizes, most of which are the standard ‘A’ formats used in the UK, but my preferred size is A3. I find I am most comfortable drawing on a surface where my hand can rest without falling off the edge. An A3 book is still portable, but not as portable as the A5-sized version that I use when making quick colour studies of plants in the field.

The smallest sketchbook in my possession is an A6 one (9 × 14cm), which I bought to try to develop a pocket-sketchbook habit; however, its small size did not work for me. The smallest sketchbook I do get on with is A5 (14 × 21cm) in size and is suitable for small sketches and colour studies. The next size up is A4 (19.5 × 29cm). This is the most popular size of sketchbook available and is the standard size of paper used in correspondence and stationery. Many of my older sketchbooks are A4-sized, but in more recent years I have settled on A3 (29.5 × 42cm) as my favourite. The A3 sketchbook allows for larger parts of plants to be drawn, and I enjoy the sensation of drawing without feeling cramped or crowded by the edge of the paper. My larger watercolour paper sketchbook is also A3 in size, providing me with plenty of room on the page to draw larger subjects and add many separate details to a single page.

Binding and Opening

Sketchbooks are primarily bound in three ways: stapled, spiral-bound or sewn. Each type has advantages and disadvantages that influence the way they can be used.

Various types of sketchbook binding: (bottom to top) stapled, spiral (plastic and metal), sewn, concertina.

Because the Fabriano ‘Venezia’ sketchbook is sewn-bound, the user is able to work across a double-page spread. This study of the snowdrop Galanthus elwesii was developed over two growing seasons. As there was no plan, the composition spread organically across the two pages, starting on the right-hand side with the plant’s fruit and seeds. The 200gsm paper is tough enough to take repeated erasure and accept some wet media. When working across two pages, I always choose a folded single page so that there is no gap between the two halves, only the binding thread.

Spiral-bound A3 watercolour-paper sketchbook used in a horizontal (landscape) format to sketch hyacinth bulbs.

Stapled books are made up of larger pieces of paper stacked and folded and then stapled in the centre. There is a limit to the number of pages that can be bound in this way, so stapled books tend to be thinner than other types. Because they have fewer pages, they are lighter and more portable and useful for travelling, but they are usually covered in less rigid cardboard so need more resting support.

Spiral-bound sketchbooks have pages perforated by holes along one edge of the paper and held together by a metal or plastic binding structure. This type of binding allows for a larger number of sheets to be bound together than stapling. A variety of paper sizes and weights can be accommodated, and the paper is not folded. One significant advantage of a spiral-bound sketchbook is that it lies perfectly flat when opened out. A disadvantage is that the spiral binding can get in the way of the hand of the artist, especially a left-handed person. If the spiral binding is bothering you in this way, you can turn the book around and either use the paper in a horizontal position, or work in a vertical position but with the binding on the side opposite to your hand. Another disadvantage with a spiral-bound sketchbook is the tendency of the metal binding to disfigure and unravel itself after repeated openings.

Sewn binding, or thread-sewn binding, creates a book with a spine and represents the most secure way of holding paper in place. As the name suggests, thread is sewn through the fold of a folded sheet or sheets of paper. Bindings can take many forms. For example, multiple sheets of paper may be folded into bundles and sewn, or a single folded sheet may be bound individually before the lot are sewn together. One advantage of a sewn-bound sketchbook is that, unlike a spiral-bound book, it allows the artist to work across the fold between two pages. Only the stitching is in the way, and this can be worked over or even used as a feature of the artwork.

It is also important to consider how you would like your sketchbook to open. This is determined by the position of the binding, which will be either on the long or short edge of the paper. You can turn your sketchbook around to suit your need for a horizontal or vertical format.

Finally, a concertina sketchbook consists of a single folded piece of paper, or several pieces glued together to create a single, long piece of paper, folded into equal-sized pages, which create a continuous surface on which to draw. Each ‘page’ is interrupted only by the fold or valley on which you are working. You can potentially work on a continuous long piece that is revealed by extending the entire paper out of its end boards. One advantage of this type of sketchbook is that, as it has no binding, it is relatively easy to make yourself.

Paper Type

Sketchbooks are produced with many different types of paper. The choice can be slightly overwhelming, so the first step is to ask yourself what you want from the paper. Are you using predominantly dry media such as graphite pencil and pen and ink, or would you like to use wet media such as watercolour? Do you need a paper that will give you sharp lines for smaller details? The answers to these questions will help you start to choose. Sketchbooks suitable for botanical work contain both cartridge paper and watercolour paper.

The spiral-bound A3 sketchbook used in a vertical (portrait) format. Any rectangular-shaped sketchbook can be used either horizontally or vertically, depending on the shape of the subject and how you prefer to work.

Concertina-style sketchbooks are popular, and fun to use. They are also the easiest type of sketchbook to make yourself, as they do not require stapling or sewn binding. This sketchbook (top) was handmade under the instruction of printmaker Frances Kiernan, while the one below was commercially manufactured. It is currently waiting to be drawn on.

Paper Weight

The first and most important aspect of the paper is its weight. Paper weight (which could also be described as ‘thickness’) is measured in ‘gsm’, or grams per square metre. The higher this number, the heavier the paper. A heavier paper will be stronger and take more erasure. If the cartridge paper is over around 150gsm, it may take a few layers of watercolour without buckling, but anything below that weight may suffer from the application of wet media. In that case, you may prefer a sketchbook that contains watercolour paper that is specifically designed to accept wet media. I use a combination of cartridge and watercolour paper sketchbooks, and prefer the paper weight to be at least 160gsm.

Paper Texture

The next important factor is the texture or surface of the paper. Do you want a very smooth surface, or do you prefer a bit of texture or ‘tooth’? Working with graphite pencil on paper that is too smooth can result in a shiny line that smudges on the page. However, that surface may be perfect for your ink pens. A smoother texture is more suitable for work with very fine detail. The appearance of a rougher paper texture adds an element of interest to a piece of work. Each surface reacts differently to the same media: for example, pen applied to textured paper will give a line that is more feathered than the sharp line that will be achieved when the pen is applied to smooth paper.

Manufacturers’ labels showing paper weight in both metric and imperial. The weight indicates the thickness of the paper. Most of my sketchbooks are at least 160gsm.

I like to feel a paper’s weight and texture with my own hands before purchasing a sketchbook. It is perfectly reasonable to approach a manufacturer or art supply shop (in person or online) to ask for paper samples. Aside from the practical considerations, there is an instinctual need to enjoy the paper with which you are working, and touch plays a huge part in this process. Once you have found a surface that you enjoy using, you may be inclined to stick with it. Be aware, though, that manufacturers sometimes change the type of paper used in a particular brand. In this case, you may need to seek out a replacement or an alternative.

Paper Colour

In terms of paper colour, you need to be aware that there are different types of white, ranging from warm and creamy to cool. A cooler white suits more technical botanical drawing, such as that for scientific botanical illustration, where visibility and clarity of detail are very important. A creamier white may be more appealing if you want your artwork to have a warmer feel to it.

An A5 Strathmore sketchbook with warm grey paper was the perfect portable surface for capturing these tiny fungi, using white and grey pens.

Sketchbooks also come in a variety of tinted and coloured papers, including cream, tan, grey and solid black. A toned paper can lend a certain warmth to drawings. The background colour also provides a mid-tone to drawings, and highlights can be added using opaque pencil, pen or paint. On black paper, it may be necessary to use dry or wet media with a higher degree of opacity than for white paper. I would find it difficult to use a transparent medium such as watercolour on a toned paper without first laying down an opaque white layer, but I do find toned papers lovely for use with ink pens.

OTHER TYPES OF PAPER

Tracing paper is useful in many ways. If a drawing in the sketchbook is becoming so overworked that you can no longer make sense of it, you can try placing a piece of tracing paper over the top of the drawing and drawing on it to help you rediscover the simple forms in the sketch. Tracing paper can also be used to transfer a drawing from one page to another. It can be folded to make small pockets for holding pressed plant material, or to protect the facing pages of a page where a pressed specimen has been mounted.

Tracing paper being used to protect the sketchbook paper surface from the damp, muddy snowdrop bulb while still seeing the drawing beneath it.

The outer and inner perianth segments, the ovary and stamens of the snowdrop Galanthus elwesii dissected and laid out on graph paper with 1mm squares – excellent reference for recording their height, width and shape.

Graph paper can be used to observe small plant parts. By placing the parts on top of graph paper with 1mm squares, it is easy to read off measurements. You can also draw up a larger-scale grid to draw those parts at an enlarged size. Photographing small parts laid out on graph paper will provide accurate reference material.

MAKING YOUR OWN BOOK

Many artists like to make their own sketchbooks. The benefit of making your own is that you have control over the size of the book, what type of paper it contains, and what cover and binding you use. You can for example use the same type of watercolour paper for your sketchbook that you would normally use for finished pieces. You could also make a concertina-type sketchbook, which will allow you to stretch out multiple drawings over a continuous sheet of paper.

If you are documenting a singular project, such as plants from a particular place or time, a custom-made sketchbook will allow you to determine the exact size and shape required to fill the book for that unique project. Making your own sketchbook has never been easier, as there are plenty of how-to videos and instructions online.

DRAWING MATERIALS

Pencils

A graphite pencil is the most important drawing tool for a botanical sketchbook. Pencil work underlies many other techniques, such as watercolour and pen and ink. As they can be repeatedly erased and replaced, pencil lines are invaluable when developing a study from a rough sketch all the way through to a detailed drawing. A pencil is extremely versatile, as it can be used in different ways to create a wide variety of marks. With a highly sharpened point, it will capture the finest lines and detail. Laid on its side and applied gently in small ellipses, it will add smooth shading and tonal values. If drawing quickly and sketchily, the looser marks of a pencil can add character and life.

There are three types of pencil that are useful for botanical drawing: wooden pencils, lead holders (also known as clutch pencils) and clutch pencils with very small leads. I do not use the latter, as they cannot be sharpened in the same way as wooden pencils and 2mm lead holders.

Drawing equipment laid out on an A3 sketchbook pad: 1. A lead pointer sharpener. 2. Dividers and proportional dividers. 3. Spare 2mm leads. 4. 2mm lead holder clutch pencils. 5. Sharpened wooden pencils. 6. Scalpel blade for sharpening wooden pencils. 7. Fineliner ink pens in grey, black and white. 8. White plastic eraser. 9. Ink pens from various brands.

My green Staedtler lead holder carries an HB lead, and my blue Mars Technico a 2H lead. This was accidental but very convenient, as I can easily tell them apart when swapping between the two. The fine point of a wooden pencil can easily be broken in transit. Retracting a lead into a lead holder provides protection for a sharp tip.

Sharpening Pencils

Wooden pencils are best sharpened using a blade or scalpel, to achieve a long, sharp point that will be versatile for both line and shading work. Traditional wooden pencil sharpeners do not provide such a long point, although there are some specialised sharpeners that manage to mimic the blade-sharpened point quite well. A blade can also be used to sharpen a lead holder, but a ‘lead pointer’ sharpener is also very useful for keeping a point on these pencils.

Sharpening a wooden pencil with a blade. 1: Traditional sharpener. 2: Carving away wood with a blade to expose a long lead tip (3). 4: The finessed point. On the final stage, be sure to sweep the blade gently past the tip, otherwise a lump of lead will accumulate there.

Sharpening a 2mm lead holder using a lead pointer tub: measure the tip to the required length using one of the guide holes marked with a triangle; insert it into the sharpening hole; keeping a steady, even pressure, move the pencil in a circular motion around the tub, so that the lead rubs against the metal cylinder inside. After sharpening, remove the pencil from the tub and wipe off excess graphite.

My preferred pencil is a lead holder pencil with a 2mm lead. There are two main benefits to using this type of pencil. First, they are easy to sharpen – there is no need to carve away wood as on a wooden pencil. They can be sharpened with a blade, as above, or sharpened using a lead pointer designed specifically for them. Second, the sharpened lead can be retraced into the holder when not in use. This makes lead holder pencils very portable, as there is less chance of the lead breaking when carrying materials around.

Pencil Hardness

The two lead grades I use most are 2H and HB, but in addition I often use softer leads such as B and 2B. The darkness of a pencil line will vary according to the type of paper being used, so this is not a definitive rule or guide. Many people find that using a hard lead such as 2H causes them to draw more ‘tightly’ and dig into the paper. When this type of lead is being used for initial drawings, care must be taken to use it with a light hand to avoid hard lines and unerasable indentations. It is, however, invaluable for capturing very fine detail, as it provides a super sharp line.

Another benefit of the 2H pencil is that when used in under-drawing for wet media, it is less prone to bleeding into paint or pen and ink placed over it, so watercolour paint applied over the top will not be excessively tainted by the graphite grains.

Erasers

Erasers are an important editing tool. They are used not only to ‘correct mistakes’, but to erase lines and marks as a pencil drawing progresses from rough to finished stage. I use a white plastic eraser, as I like the cleanness of it. This type of eraser must be of high quality; a poorer-quality item can tear and damage the surface of the paper. Clean your eraser regularly by rubbing its surfaces on to a clean sheet of paper. This removes the previous deposits of rubbed graphite and minimises the risk of transferring smears of old graphite on to the drawing. Most erasers come in a protective cardboard covering to keep them clean. It is a good idea to keep this covering on the eraser, only exposing the part that is currently being used.

Types of eraser: white plastic block eraser and kneadable putty eraser (above), pen-style white eraser (below). Whichever type you prefer, the quality and texture are important. It must lift graphite without damaging the fibres of the paper, allowing successive layers of graphite or wet media to be added.

There are many other types of eraser available, including white plastic erasers that come in a pen-like form. Many botanical artists like to use an eraser of kneadable putty. Its soft, pliable texture allows you to make gentle erasures by rolling it over the surface of the paper. If using a putty eraser, be sure to keep it clean as it is not possible to remove excess graphite from its surface.

Ink Pens

A wide variety of ink pens and inks can be used in the botanical sketchbook. Ink can be used on its own to sketch free hand or placed over a pencil under-drawing. It can also be combined with watercolour. Whether you use dip pens (nib pens), technical drawing pens such as those in the Rotring ‘isograph’ range, or fineliners, the best and most versatile inks are those that are waterproof and lightfast. Waterproof ink will allow wet media to be applied on top of it without it dissolving. I use a selection of Rotring pens in sizes 0.10, 0.25 and 0.35, plus black fineliner pens from various brands, in sizes ranging from the smallest (0.03) to 0.2. In addition to the black ink pens, I also have some that carry grey ink, and a white Sakura ‘Gelly Roll’ pen for adding highlights to ink drawings on toned paper.

Fineliner pens are available in both black and grey, and I have a variety of them, including Uni Pin, Staedtler, Derwent, Sakura and Rotring ‘Tikky graphic’. My Rotring pens are reserved mainly for scientific illustrations. The white Sakura ‘Gelly Roll’ pen is used to add highlights to ink work on toned paper.

I carry my drawing pencils, pens and eraser in an old-school zipped pencil case. I carry only what I need at the time; everything else can stay in a drawer. This bag was actually designed as a make-up bag, but was of more use to me for carrying drawing equipment.

DRAWING EQUIPMENT

Dividers and Proportional Dividers

Dividers allow you to take measurements directly from a plant specimen. This is very helpful in achieving accuracy in measured drawing. The length, width or angle of a part of the plant may be ‘measured’ by expanding the divider’s points to match the observation and then transferring the dimensions to the paper via the dividers, so that the line may be drawn.

Enlarging and reducing with Ecobra proportional dividers: setting the dividers to ‘3’ allows the flower (top) to be measured and enlarged to three times its size (‘×3’). With the dividers still set to ‘3’ but flipped the other way, the seed pod (below) has been measured and reduced to one third of its size.

Proportional dividers go a step further, enabling a measurement to be enlarged or reduced immediately on transferral to the page, by use of a sliding scale. They have a sliding mechanism, which, when adjusted to the required number, allows the user to take a measurement and then either reduce it or enlarge it when transferring the measured line. For example, if the proportional dividers are set to ‘3’, a dimension that is measured with the smaller opening of the points becomes tripled when it is transferred to the paper. The opposite result is obtained by measuring with the wider of the point openings. When transferred using the small opening, the measurement will be one-third.

Desk Easel or Drawing Board

When working in the field, you may simply hold the sketchbook on your lap, but on those days when you are based in the studio, it is advisable to work on a raised surface. This will be better both for the observation angles and for your posture. I work on a lightweight wooden-framed table easel, which can be raised and set at a few different angles. The frame easel will support a variety of drawing board sizes, or the sketchbook itself can sit directly on the easel. When working outdoors you may wish to take a wooden or cardboard drawing board to support the sketchbook and/or prop it against something to keep it raised.

A lightweight wooden frame desk easel, which can be adjusted to four heights. Drawing boards of various sizes can sit on it, or a larger sketchbook can be laid directly on it. Drawing at an angle is beneficial for the posture, and it is also better for capturing live specimens, as the drawing surface is held at a similar height to the subject.

PAINTING MATERIALS

Watercolour

Watercolour paint is the mostly commonly used colour medium in botanical art and illustration. There are other colour media, including coloured pencils, gouache, acrylic paint and oils, but watercolour paint is particularly well suited to use in a botanical sketchbook. This is because it tends to mimic the qualities of flowers with its translucency. The same translucency allows watercolour to be built up using layering, which permits controlled application and development of colours and tonal values. Not only can colour be applied quickly over large areas, but also, by reducing the dilution of the paint and using only the tip of the brush, very fine detail can be added. Just as observation of plant structure and form is ideally made from life, so too is the observation and replication of plant colour. Another benefit of using watercolour paint is that it is very portable, especially when used in pan form, and requires only a few brushes and the addition of water.

Over time, a botanical artist will build up their own unique preferred palette of colour choices and a repertoire of colour mixes, both remembered and documented. However, beginners may be overwhelmed at first by the range of pigments available. It is therefore helpful to have some understanding of where to start when buying watercolours. Generally, I work with a palette of primary colours and try to mix most of my final shades and tones from these. At times, however, this supposedly restricted palette expands, alongside some pigments that just need to come straight from the pan or tube, with minimal mixing!