Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

At the end of the Second World War, hundreds of thousands of German children were sent to the front lines in the largest mobilisation of underage combatants by any country before or since. Hans Dunker was just one of these children. Identified as gifted aged 9, he left his home in South America in 1937 in pursuit of a 'proper' education in Nazi Germany. Instead, he and his schoolfriends, lacking adequate training, ammunition and rations, were sent to the Eastern Front when the war was already lost in the spring of 1945. Using her father's diary and other documents, Helene Munson traces Hans' journey from a student at Feldafing School to a soldier fighting in Zawada, a village in present-day Czech Republic. What is revealed is an education system so inhumane that until recently, post-war Germany worked hard to keep it a secret. This is Hans' story, but also the story of a whole generation of German children who silently carried the shame of what they suffered into old age.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 397

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

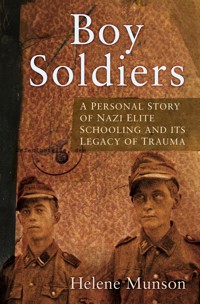

Cover image: Hitler Jugend Soldiers of the 12th SS Panzer Division. Captured by the United States Army during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944.

Back cover image: Hans, aged 10, in front of St Stephani church in Bremen during the winter of 1937. (Helene Munson)

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Helene Munson, 2021

The right of Helene Munson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-7509-9908-3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

‘If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it.’

Joseph Goebbels

‘Thou shalt not take vengeance, nor bear any grudge against the children of thy people …’

The Torah, Leviticus 19:18

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction: Závada Revisited

1 The Wrong Time to Die

2 Travelling to Another Country

3 The Vanished Boarding School

4 Not a Napola

5 Castle Birdsong

6 Schooled by Barbarians

7 The Flag is More Than Death

8 Franz and the FLAK

9 Glasses and Mineral Water

10 Barrack Blues

11 Dresden and Departures

12 Arriving in Sudetenland

13 The Battle for Zawada

14 Saved by a Grenade

15Germanskis on the Run

16 A Long Way Home

Epilogue 1 The Back-to-Front File

Epilogue 2 The Glass Cabinet

Appendix I List of Locations

Appendix II List of Abbreviations and Glossary

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

This book would have never happened were it not for the kindness of Siobhan Fraser and her husband, Alyn Shipton, who both saw potential in my project. Alyn agreed to help me with editing, giving thoughtful input and pulling it all together. I would also like to thank my talented and dedicated editors, Amy Rigg and Alex Boulton. Thank you to Anette Fuhrmeister and Jennifer Hergenroeder for taking my story out into the world. My gratitude also goes to the whole team at The History Press for courageously taking on a book project on a so far mostly unexplored and forgotten aspect of German history. Until I met them, writing had been a lonely pursuit, as I encountered negative feedback, especially from my German compatriots, who felt that the dead should be left dead and let sleeping dogs lie. But they reinforced my resolve to bring the story of Hitler’s forgotten victims, Germany’s own children, to life.

I am indebted to the support of Stefan Wunsch, academic director of Vogelsang IP | NS-Dokumentation Vogelsang, who kindly fact checked the chapters relating to National Socialist (NS) elite education. Many smart suggestions to improve the manuscript were made by Dave Porteous, Joyce de Cordova, Suzi Rosenstreich, Kit Storjohann and Andrea Rhude from my beloved North Fork Writers Group. Andrea Lorkova, the current mayor of Závada, and my avid reader Gonzalo Tellez never lost confidence in my project. Thank you to friends and family for critiquing early drafts. My gratitude goes to all of you whom I met along the way, who put up with me passionately talking about the subject and who encouraged me to keep writing, when at times the research took a toll on me, questioning my belief in a world that is capable of such monstrosities.

I pay special homage to the writers who came before me, especially Erika Mann with her visionary book School for Barbarians, published in 1938. With frightening accuracy, she foretold the terrible things that my father and 10 million other German children would be going through in the following years. I hope that my book, the tragic illustration of the exactness of her predictions and its sad aftermath will serve as a warning to today’s world where radical regimes still send ideologically brainwashed children into war.

Every effort has been made to trace and attribute copyright holders. In the case of any omission, please contact the author care of the publishers, so that it can be rectified in future editions.

Introduction

Závada Revisited

Some of us have family members who had fascinating lives that inspire us – some of us have relatives whose lives were memorable, but troubling to contemplate. I had both in my father, known as Dr Hans Dunker – a PhD in History, Ambassador for the Federal Republic of Germany, a family man and a dedicated church alderman. But he was also one of Hitler’s boy soldiers and saw violence and evil that no child should witness, let alone be party to. The dark days of his childhood left him unable to talk about it. Instead, he bequeathed to me his boxes of carefully collected documents and the Second World War diary he had written.

After my father’s death, I banished the document boxes into the basement of my apartment in Berlin-Kreuzberg, unable to face whatever they contained. What could have been so important that my father had kept those papers, transporting them from country to country as his diplomatic career required him to move around the world?

Six years later, I attended a course at Oxford Brookes University focusing on armed conflicts and children in war-torn countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) or Afghanistan, making me realise the importance of my father’s child soldier’s eyewitness account.

But the boxes contained much more: albums of sepia-coloured photos, expired IDs from countries that no longer existed, letters written on translucent, thin airmail paper and once-urgent telegrams. A second diary had been written when he attended Feldafing, an elite Nazi school.

As I unpacked the containers, the story unfolded. Being singled out as an extremely gifted child at age 9, he was separated from his parents who lived in South America. They, in the misguided belief that a German boarding school would best serve their son’s potential, inadvertently turned him over to an elite Nazi educational system so controversial and inhumane that, until recently, post-war Germany has worked hard to keep it secret. When the school sent him into active combat at age 17, he was already accustomed to seeing death. He and his classmates had been shooting down enemy planes since they were 15 years old. But what happened in a small eastern village just before the end of the war would devastate and cripple him.

Hans’ poignant account, starting in early spring 1945, detailed how he and his schoolfriends, badly trained, with neither enough ammunition nor sufficient food rations, were sent to the front wearing makeshift uniforms – at a time when the war was already lost.

Originally, I intended to publish the war diary on its own, as a warning to a world still sending children into battles, oblivious to the true cost to society, not just to the underage soldiers, but their families and future generations. After working on the diary – translating it, researching its historical context and interviewing eyewitnesses to substantiate its accounts – my work felt incomplete. I needed a deeper emotional connection to understand what had really happened to my father, leaving him with a post-traumatic stress disorder that had affected our family for decades.

On the first page of my father’s yellowed and brittle diary was one word: Zawada.

I discovered that Zawada was a little village with great significance for him. Eventually I located it, after cross-referencing the name with surrounding towns mentioned in the diary and determining that the German ‘Zawada’ was now the Czech ‘Závada’, spelled with a ‘v’ instead of a ‘w’. I ruled out several other villages with the same name in Poland, since I knew that my father had fought in what is now the Czech Republic but until 1993 was part of Czechoslovakia, in an area Sudeten Germans had inhabited since the Middle Ages. Using a place-name dictionary published by displaced Sudeten Germans, I reconstructed a pre-Second World War map of the area.

In old age, my father could have returned to Zawada, once West Germans were allowed to travel into the former communist states after 1990, when the Cold War had ended. But my mother told me he had refused. They had only travelled as far as Pirna. By the time I read the diary, he was dead. I felt obliged to complete the journey for him. After translating the village’s Czech website, I sent an email in English to Závada’s mayor.

The mayor’s English-speaking assistant, Andrea Lorkova, sent me a kind reply and invited me to visit. In March 2013, I started out from Berlin and headed towards Dresden on the autobahn, rebuilt with several lanes after Germany’s reunification in 1990. The new highway system once again connected the two parts of Germany. I followed my father’s original route from Berlin; his cattle train had stopped on the outskirts of the city on the way to the Eastern Front.

When I first read the diary, the place names Hans mentioned meant nothing to me. For my generation of West Germans, the areas south and east of Berlin were blank parts of the map, hidden behind the Iron Curtain. Now these places appeared before my eyes. The weather was just as cold and unpleasant as it must have been when my father was deployed in the spring of 1945, with snow flurries and a still-frozen ground. After a two-hour drive, I reached Dresden and enjoyed a stroll through its carefully rebuilt historic city centre; the city once more a magnet for culture and art.

Dresden was in total ruins when Hans travelled through. When the Allies dropped a record number of bombs on the city in 1945, Dresden was overflowing with thousands of desperate refugees. Among them, hundreds of children were killed.

After Dresden, my route narrowed to a single lane, involving hairpin curves over mountain ranges and winding through farming villages with speed restrictions. I stopped at the small city of Pirna, 16 miles south of Dresden, where Hans had stayed in a hospital for several weeks. The kindness of Pirna’s inhabitants, who had shared their own meagre rations with the injured boy soldiers, left a lasting impression on him. I passed the turn to the small town of Bad Gottleuba, where my father spent another month in a sanatorium, recuperating from his injuries. I decided not to stop, as I wanted to reach the Czech Republic before dark. The drive took me through ‘the Switzerland of Saxony’, with its dramatic mountain ranges and deep forests. In the fading light, I drove through the valley of the River Elbe with its spooky, bizarre rock formations – just as Hans had described it.

I spent the first night in the Czech border town of Děčín, once known as the Sudeten German town of Tetschen. I chose to stay at the Hotel Faust, an image of the devil Mephisto gracing its entrance hall. Goethe’s play with the same name had been my father’s favourite. He carried the book with him during his whole ordeal.

The next day, I drove over a mountain range through several villages in which the famous Bohemian crystal is still produced. Glistening chandeliers could be seen in small shop windows that advertised outlet sales. I passed several antique shops and decided to stop at one. Many items had German writing on it – a first aid kit, kitchen utensils and toys. I found some Karl May books in German and imagined that a little boy, just like my father, must have once considered them among his most cherished possessions. Photo albums had been torn apart and the images were sold by the piece. Presumably these things, which still filled the entire antique shop from floor to ceiling, had belonged to the 3.5 million Sudeten Germans who had to leave everything behind when they were driven out by the Czech population at the end of the war. I picked up a heavy, rusty, black metal helmet with hardened brown leather straps. The store clerk informed me it was German. I wondered what had happened to the man who had once worn it. The items were quite inexpensive, and I would have liked a souvenir of this trip, but every piece had a sad story to tell and I wanted none of it.

The next day, I noticed a large, grey concrete bunker by the roadside. I stopped the car and walked around it. Here was some tangible evidence of the war I had come to rediscover. The bunker’s interior was accessible, but I was hesitant to walk into the dark, cavernous space without a torch.

As I continued, I saw so many more bunkers. Soon I did not bother to stop – I later learned that more than 10,000 still exist. Originally, I assumed that the German Army had built them, but learned that, instead, the Czechoslovak government had constructed them between 1935 and 1938 to defend its people against the Germans. In a tragic irony, the 1938 Munich Agreement turned the situation around. By granting Hitler the Czechoslovak areas settled by ethnic Germans as protectorates, those lines of defence fell into German hands.

Shortly after lunch, I arrived in Závada, exhilarated to have made it to the place I had imagined so many times while reading the diary. Looking at a few remaining older buildings, I realised that my father would have seen them too. In the middle of the village stood a small, pink church and, next to it, a stone crucifix. A German inscription at the stone base, dated 1898, used the original German spelling of the village name: Zawada. It felt strange standing at the spot where the fighting took place. I stood where my father had stood, separated by sixty-eight years, almost to the day.

Andrea Lorkova, whom I had corresponded with, met me in the village square and took me to the mayor’s office. Jan Stacha, a handsome man of 62 with strikingly blue eyes, straw-blonde hair and a light complexion, received me warmly. He made a lighthearted joke about himself looking very German. Andrea brought coffee and cake. Our meeting was emotional, with all of us talking about how the Second World War had affected our families. While my father was brought to fight in this village, the Wehrmacht (the armed forces of Nazi Germany) had drafted Jan’s father and uncle away from Závada to fight at the opposite end of the Reich. Only women and children were left behind; they either hid in their cellars or fled to relatives in Ostrava, which was perceived to be safer but was also besieged towards the end of the war, as Hans had noted in his diary.

Jan retrieved a map of the village and produced the official village chronicle. For generations, each mayor had recorded village events as a historical record for his successors. Jan read the entries for the days my father was there, 17–20 April 1945, and Andrea translated. Although the chronicle addressed the loss of civilian life and contained an exact count of the remaining livestock, no combat details were included.

I asked many questions: ‘Where did the old manor house stand? …Where was the village well?’

Jan was astonished at my knowledge of the village, based entirely on the diary. He confirmed what I had suspected: Hans’ account is the only known eyewitness record of those fateful days in Závada. In this diary entry, Hans recounted the day he was wounded:

In the morning of the third day the commander gave us some recognition for sticking it out in this windy corner, and the announcement that the general attack of the Russians was imminent. The remaining parts of our platoons had been significantly decimated and our defence became weaker … After one hour of being under heavy drumfire, you had the weird … feeling to stand up. Under great pains the faithful Wenzel managed to keep me down … The gaunt König carried you back. You had been hit.

The battle ended with the total annihilation of his army division, but my father did not write about that. Combat ended for him when he was wounded. I wanted to leave a copy of my father’s account in Závada, so I had brought photocopies of the diary and its English translation for the village archive.

I spoke to Jan and Andrea about my father, his school friend Karl, who died in the battle, and the other boys from his school class – Gerd, Georg, Albert and Dieter – whose fates were unknown to me. Nor did I know what happened to the other men, or their bodies, who had fought alongside my father – Wenzel, old Martenson, König, the shepherd Hans and platoon leader Hoffmann. I asked Jan where the German soldiers were buried. He told me that both armies retreated without being able to carry their dead. The few villagers who had been hiding in their cellars came out and were overwhelmed by death. They counted the bodies of ninety-eight German soldiers and eighty Russian soldiers that lay scattered all over the village. The townspeople dumped the bodies, regardless of nationality, in ditches in the street or in holes they dug in their backyards. Nobody bothered to ask who they were or mark the sites. But Jan recounted one incident that Andrea translated: ‘One woman retrieved personal documents from the body of the dead German she found in her yard. After the war was over, she mailed them back to his wife in Germany.’

In February 1948, Czechoslovakia came under Russian influence and the remains of the Russian soldiers that could be retrieved with the help of villagers were given a proper burial – but not the German bodies.

I told Jan that I was sorry for all that happened, and I was sure my father had felt the same way. Jan and I both expressed our regrets that my father hadn’t made the trip back to Závada. He might have been less reluctant to face his painful memories once again had he known what a kind reception awaited him. To my apologies, Jan responded, ‘The past cannot be undone, but we can try to make the future better.’

I spent the rest of the afternoon with Andrea at a bunker we identified, based on my father’s description and some calculations on the map. This was where Hans was taken after he was hit by pieces of a grenade. The bunker, a very large structure, sat abandoned in a stretch of woods still visibly streaked with now-overgrown trenches. Like my experience in the town centre, I had an odd sensation standing in the silent forest which, in 1945, had been covered with abandoned military paraphernalia, dead men and wounded soldiers waiting for first aid and contemplating their fates.

Reconstructed defences and fortifications not far from Závada. (Helene Munson)

No hotels or guesthouses existed in Závada, but as we returned from our afternoon excursion, Andrea kindly offered me her daughter’s room. In the evening, we talked about war, peace and the future of our children. We did not know it at the time, but two years later, Andrea would replace Jan Stacha as the mayor of Závada.

I told Andrea that I wanted to have a prayer said for the German boy soldiers in the little pink church. Our family had been Lutheran for many generations. While religion had not been a major part of my life, it had been very important for my father, who served as a church elder in Rheinbach, the town where I grew up, for many years.

The next day was Good Friday. Heavy snowflakes were falling when Andrea and I stopped at the priest’s house across the street from the church in the neighbouring village of Bohuslavice. Závada’s church had no clergyman of its own.

The nameplate announced that the priest’s name was Kazimir Buba. The blonde young man who opened the door was dressed stylishly in a checkered flannel shirt and jeans, looking more like a hipster than a clergyman. Andrea explained my request in Czech and he asked us in. He said that he spoke a few words of German but preferred for Andrea to continue to translate from my English to Czech. He ushered us into a room with a large, round table and bay windows that looked out onto a tranquil lake. It felt like the kind of room where many people had already comfortably poured out their hearts.

I talked about the six boys from Feldafing School and that Karl Hacker’s body was somewhere out there in the grounds of Závada. Andrea translated and Kazimir Buba listened. I wrote down the names of the six boys and placed the list folded with some Czech Koruna banknotes on the table. I had learned from my days of visiting places of worship in the Ukraine that it is customary that a request for prayers should be accompanied by a small personal sacrifice. Kazimir Buba reached into a drawer to issue me a receipt for my church donation. I told him that I did not care for a piece of paper. All I wanted from him was to promise me that he would pray for the six Feldafing boys next time that he was holding a prayer session at the little pink church in Závada.

From my bag I pulled out six red candles with tin covers and asked him if there was a way to light them. He looked straight at me and promised he would pray for the young soldiers. Seeing the anguish in my eyes, he asked me politely if I would like to see the Bohuslavice church next door. Not sure why he was suggesting it, I nodded. We crossed the street and just before the church entrance, he stopped in front of a memorial to the village’s local soldiers and war victims.

My eyes wandered over the marble slate and started reading: ‘Postulka, Alois, born 1928, died 1945 … Kotzur, Hans, born 1936, died 1945.’ The children of this village had also been senselessly slaughtered in those last weeks of war. Pastor Buba motioned me to place my six candles next to the ones already in front of the memorial. Andrea took a candle from my hands and, as we struggled to light it in the snowy wind, she said, ‘This one is for your father.’

The priest folded his hands and spoke a prayer in Czech. When he saw my tears, he began to recite the Lord’s Prayer in German. I joined in, and when he could not remember the last few lines in German, I completed them. This prayer was the one I had not spoken with my father at his deathbed and wished I had. I was moved to see candles for my father and his friends lit and placed underneath a memorial for Second World War soldiers. And I realised that this small ceremony was probably the first and only act of commemoration for this group of German boy soldiers who were now only remembered in the pages of my father’s diary.

1

The Wrong Time to Die

The grounds around the Rudolf Virchow clinic in Berlin were elaborately landscaped. The architect, Ludwig Hoffmann, had envisioned a hospital surrounded by gardens to promote patients’ healing. When it was inaugurated in 1906 by Kaiser Wilhelm II, the layout was considered the most innovative and advanced facility in all of Europe. By 2005, the trees had grown tall and gnarly, providing shade on a warm July day. Twittering songbirds perched up high on the branches, adding to the sense of tranquillity evoked by the lush, green vegetation and the cut-grass-infused smell of summer. Partially moss-covered stone benches and some marble heads on pedestals, depicting forgotten pioneers of medical history, were spread all over the property.

I pushed his wheelchair over a gravel path and parked it next to a bench, on which I sat. It was an odd feeling to see my once statuesque father so small and fragile. The flimsy hospital gown covered by a bathrobe was an open acknowledgement that he was a man too sick to dress up to go out in public. His now thin calves were naked. A pair of my mother’s hand-knitted socks covered his feet, stuck in a pair of felt slippers. I looked away. As a little girl I remembered him dressed in a tuxedo or morning coat attending official functions, wearing the medals he had been awarded during his diplomatic missions. The most striking one was a large gold star hanging on a broad, white and blue ribbon. The colour picked up the bright blue of his eyes. How hard we laughed when my mother told us that when they had been presented at the court of St James, Her Royal Highness Princess Margaret accidentally addressed him as his Excellency the Ambassador, when he had only been the first secretary at the German Embassy.

My relationship with my father had been difficult. At times I had resented him. But he had always been there, sometimes domineering and imposing, at other times teaching me about literature and art. I was not ready to see him die. I banned the thought of death from my mind. It felt much safer. Two agile, brown squirrels chased each other playfully across the grass. It seemed very much like the wrong time of year to be dying.

In contrast to me, my father was not in denial of his situation. He sensed that he did not have much time left. An urgency to tell me about himself seemed to overcome him, as he struggled for words in deciding what to say first. Unable to remember what he had already told me in the past, he decided on a recap of his life:

I was born in 1927, in Concepción in the South of Chile. My parents were Heinz and Hilde who had left Germany after the First World War to escape the chaos of the Weimar Republic. My father, Heinz, had an uncle in Chile which must have inspired him to emigrate. My mother, Hilde, was always up for an adventure, having spent her childhood in colonial Burma.

His tone softened as he started to reflect:

You know my parents, your grandparents, never stayed in one place very long. My earliest memories are from living in Peru. Did you know that I spent my elementary school years in Mira Flores in Lima? I was so happy there! My parents must have enjoyed their carefree expatriate lives in South America. I was a cute, flaxen-headed young boy and they called me Hansito, which in Spanish means ‘Little Hans’. All my parents’ domestics fussed over me. I guess in the Latin culture all young children are indulged.

A shadow came over his face as he continued:

But all that changed for me when my parents visited Germany in 1937. They left me there to get a ‘proper’ German education. I was only 9 years old and Germany was a foreign country to me. There were so many rules to follow! I was terribly homesick, and had I known that I would not see my parents and my brother again for over ten years, I would have probably despaired. But your great aunt, Auntie Tali, my father’s sister, took me under her wings. We visited places in Bremen that would have made any child happy. There were delicious meals of Labskaus in the Ratskeller, hot chocolate and cake at the Meierei and a whole series of Karl May and Dr. Uhlebuhle adventure books at the bookstore in the Böttchergasse.

Sinking deeper into the chair, he remembered Auntie Tali:

Auntie was a spinster, like so many women of her generation. Not enough men had come home from World War One. I became the child she never had. She doted on me when I was staying with her in Bremen. I was particularly excited when paddling with her in the folding Klepper canoe on the River Weser. I learned how to use the 8mm cine-camera she had given me. Later in the war, I filmed the planes that we boys had shot down when we were in the FLAK.

He paused for a moment; then he recounted his earlier experience of arriving in Bremen: ‘At first, I was supposed to stay with my mother’s parents, Johann and Marie. They owned a grand, old house in the Göbenstrasse in Bremen. They lived on the same street as Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck.’

‘Who was he?’ I interrupted.

‘You don’t remember him from your school history lessons?’ he asked, somewhat irritated.

‘No, we were never told about him. There are lots of things that we were not taught,’ I responded somewhat defiantly.

‘He was to the Germans what Cecil Rhodes was to the British: a hero during Germany’s brief, ill-fated, colonial aspirations,’ he explained, assuming correctly that I had at least heard of Rhodes. Returning to his original story, he continued:

My mother’s parents were old school and felt that, according to the educational maxims of the time, children were to be seen, not heard. Grandfather Johann had been the German consul in British colonial Burma. Grandmother Marie had been a grand dame in the Rangoon expat society. She raised my mother, Hilde, and her other two daughters with the help of fifteen servants. My grandparents were nice enough but had little patience with a young boy. So, I went into the care of my father’s family, more precisely Auntie Tali. She was a teacher herself and had convinced my parents that it would be best for me if I were to attend a first-rate government school with other children instead of living with my ageing, inattentive grandparents. The school she suggested was special. Only the best and the brightest Aryan boys were accepted. It was she who convinced my parents that by attending Feldafing boarding school, I would be guaranteed a bright future in Germany, or as an Auslandsdeutscher if I chose to return to South America.

His mood changed to a brooding. Almost to himself he mused, ‘How differently might my life have turned out if I had returned with them to Peru.’

My father looked cold. He was so thin now; I spread a blanket over him. For a while we sat next to each other in silence. The sun was lower now, and the frolicking squirrels had been replaced by dark shadows growing longer and longer. I wheeled him back into the building.

The next day, I arrived earlier at the hospital to catch more of the warm afternoon sun. I asked an orderly to bring a wheelchair and as two men in white uniforms tried to lift my father into it, he grimaced in pain. With a tired movement of the hand, he asked to be returned to his bed. I sat down next to the bed expecting him to continue his story from the day before. But he stared into space saying nothing. Suddenly he grabbed my wrist and pulled me towards him. Looking straight at me, he asked urgently, ‘You have read Zawada, haven’t you?’

I remembered that about a year earlier my father had visited and placed a cloth-covered diary on my living-room coffee table. It had the word ‘Zawada’ written on it.

‘Maybe you’d like to read the diary I wrote when I was a schoolboy and they sent us into combat on the Eastern Front?’ he had suggested.

The months went by and I picked it up only once, reading a random passage in an earlier chapter:

Marching in a row towards the dark woods, the moon is protecting its shining brightness with a thin veil of clouds in the middle of a deep, dark, fairytale-like blue. Every small leaf of the trees appearing coal black, which longingly reaches towards the light, defends itself against the yellow paleness with which the lower part of the horizon is gradually being filled … pours itself against the magnificently displayed cloud art!

Impatiently skipping passages, I continued:

Unstoppable and unforgiving a golden wall of light pushes itself over the celestial sphere. Bonded with purplish, reddish, yellowish and at last saturated, penetrating gold, the untiring cloud group continues its play of lines, circles, vortexes, silhouettes and veils: form and emblem at the same time! In its eternal purity the vessel of the blue celestial sphere is holding all together in its holy circle. And the small group of humans continues to stride through the silent, still landscape of mounts. The earth is always ready; she can change in an instant in the most amazing ways. There, a ruby red flash through the tangled brambles! But the view is soon hindered by the dark shadows of the woods. The way leads below a heather heath. The tips of the heather bushes are radiating on top of crests … The blue has almost vanished …The eternal announcement of light has happened.

I put the book down in disgust. The language was over the top; the description of a sunrise was overwritten. Occasionally, he had used such language in real life. I resented him for it. It had put distance between us. It would take me years to understand that this language was something he had learned at school. It had been a tool to mould the boys’ emotions so that they could be exploited for a supposedly higher cause. If I had cared enough to read further, I would have found out that the diary contained the most heartbreaking story I would ever read, told in his own words. It was only the opening chapters that were written like a school essay gone wrong.

When my father visited again a few months later, he noticed that the diary was still in the same spot where he had left it, now covered with a thin layer of dust. He said nothing. He quietly put it back in his bag. I had the uneasy feeling that I might have missed out on something important. My father was retired now and making attempts to spend more time with us, his children. Most of his adult life he had been preoccupied by his postings as a German diplomat, organising international conferences, liaising between government officials and, most importantly to him, helping Namibia gain independence without bloodshed. According to his own definition, it had been his duty to contribute towards repairing Germany’s damaged image in the world. He had been very serious about his work and had rarely found the time to attend high-school graduations or other milestone events in the lives of his children. But now I was an adult myself and it was me who was too busy to spend time with him. Recently divorced and a single parent, I was in charge of a house in post-unification East Berlin that after years of communist negligence, needed to be renovated from cellar to roof. It was only after I found out how ill he was that I made time. Seeing his slight silhouette in a mass of white starched sheets and pillows, I did not have the heart to tell him that I had not read the diary and lied, ‘Yes, I read most of it.’

He scanned my face. I was embarrassed and wanted to avoid his gaze. Not knowing the story, I tried to look as neutral as possible. He let go of my wrist, looking into space again. Then returning to the moment, he said, ‘Never mind!’ trying to hide his disappointment. With some solemnness he added, ‘After I am gone, I would like you to safeguard the family documents and Zawada, the diary. You are my eldest, I have always relied on you. I don’t expect you to read them now, just keep them.’

Having already failed him once, I promised, giving his hand a gentle squeeze, not realising what a heavy burden I had just taken on.