29,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: McNidder and Grace

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

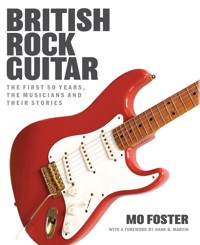

The guitar has become the most emotive musical instrument of the last 50 years of rock and roll. From the early days when wannabee stars fashioned homemade guitars out of old tea chests, to today's sophisticated instruments the impact has been phenomenal. In this book, Mo Foster, one of the industry's most prestigious bass guitarists, and renowned producer, composer and session musician draws upon his own recollections and those of some of the greatest exponents of the rock guitar, from Hank Marvin to Eric Clapton and Brian May. Once managed by Ronnie Scott, Foster has recorded and toured with many of the world's biggest musical icons including Jeff Beck, Phil Collins, Eric Clapton, Gerry Rafferty, Van Morrison and George Martin. In this insightful, passionate and humorous book Mo Foster has written the definitive history of the importance of the guitar in the development of British music over the last 50 years.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 838

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

iii

DEDICATION

For Billie and Charles, my mum and late dad, who made sandwiches for the band in spite of the baffling racket in their living room.

And for Kay, my wife, who must have heard every story at least ten times.

And lastly for my oldest friend, the late Peter Watkins, without whose inspiration I may never have become a musician. vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Extra special thanks go to:

Mark Cunningham who helped me enormously with the editing of the original book.

Kurt Adkins for re-scanning and copy-editing the original text, and restoring all of the images.

The late Ronnie Scott for showing me that it was possible to combine beautiful music with wonderful humour.

Ray Russell for guidance and enthusiasm.

Andrew Peden Smith of Northumbria Press for having the vision to make this edition possible.

Finally, I would like to extend my thanks to the following people, each of whom has made an important contribution to the stories in this book, and I apologise to anyone that I’ve missed out:

Keith Altham, John Altman, Mark Anders, Dave Arch, Rod Argent, Joan Armatrading, Tony Ashton, Ronnie Asprey, Malcolm Atkin, Roy Babbington, Tony Bacon, Ralph Baker, Paul Balmer, Terry Bateman, Bruce Baxter, Paul Beavis, Jeff Beck, Martin Benge, Brian Bennett, Ed Bicknall, Steve Blacknell, Brian Blaine, Debbie Bonham, Jason Bonham, Stuart Booth, Dougie Boyle, Rob Bradford, Andy Brentnall, Martin Briggs, Terry Britten, Joe Brown, Pete Brown, Richard Brunton, David Bryce, Peter Bullick, Peter Button, Hugh Burns, Laurence Canty, Clem Cattini, Simon Chamberlain, Paul Charles, Chris Charlesworth, Phil Chen, Roger Clarke, B.J. Cole, Ray Cooper, Peter Copeland, Jeff Crampton, Bob Cullen, Joan Cunningham, Paula Cunningham, Mike d’Abo, Mitch Dalton, Bryan Daly, Sherry Daly, Patrick Davies, Ray Davies, Paul Day, Dick Denney, Ralph Denyer, Emlyn Dodd, Shirley Douglas, Gus Dudgeon, Anne Dudley, Judy Dyble, Duane Eddy, Bobby Elliot, John Etheridge, Stuart Epps, Tommy Eyre, Andy Fairweather-Low, Neville Falmer, Ray Fenwick, Philip Fejer, John Fiddy, Guy Fletcher, Vic Flick, Graham Forbes, Alan Foster, Pete Frame, Pam Francis, Colin Frechter, Brian Gascoigne, Gordon Giltrap, Roger Glover, Julie Glover, Brian Goode, Kim Goody, Graham Gouldman, Mick Grabham, Keith Grant, Steve Gray, Colin Green, Mick Green, Brian Gregg, Isobel Griffths, Cliff Hall, Richard Hallchurch, Pat Halling, David Hamilton-Smith, Dave Harries, Jet Harris, George Harrison, Paul Hart, Mike Hawker, Alan Hawkshaw, Tony Hicks, Christian Henson, John Hill, Colin Hodgkinson, Bernie Holland, Hugh Hopper, Ian Hovenden, Jason How, Linda Hoyle, Jeffrey Hudson, Les Hurdle, Mike Hurst, Gary Husband, Neil Innes, Neil Jackson, Christina Jansen, Graham Jarvis, Alan Jones, John Paul Jones, Mike Jopp, Stewart Kay, Carol Kaye, Gibson Keddie, Adrian Kerridge, Martin Kershaw, Mark Knopfler, David Kossoff, Chris Laurence, Jim Lawless, Jim Lea, Paul Leader, Adrian Lee, David Left, Adrian Legg, Geoff Leonard, Jon Lewin, Mark Lewisohn, Julian Littman, Brian ‘Licorice’ Locking, Claudine Lordan, Wes Maebe, Ivor Mairants, Phil Manzanera, Bernie Marsden, Jim Marshall, Neville Marten, Sir George Martin, Hank Marvin, Dave Mattacks, Brian May, Brendan McCormack, Chas McDevitt, Tom McGuinness, Tony Meehan, Mark Meggido, Mickey Moody, Gary Moore, Mike Moran, Joe Moretti, Charlie Morgan, Sarah Morgan, Maurice Murphy, Jeremy Neech, Roger Newell, John Morton Nicholas, Kay O’Dwyer, Pino Palladino, Phil Palmer, Rick Parfitt, Alan Parker, Dave Pegg, Richard Pett, Guy Pratt, Simon Phillips, Phil Pickett, Willis Pitts, David Porter, Duffy Power, Bill Price, Judd Procter, Andy Pyle, Paul Quinn, Chris Rae, Jim Rafferty, Noel Redding, Tim Renwick, Sir Cliff Richard, Dave Richmond, Maggi Ronson, Francis Rossi, Allan Rouse, Ray Russell, Martin Sage, Ralph Salmins, Grant Serpell, Noel Sidebottom, Lester Smith, Marcel Stellman, Jim Sullivan, Andy Summers, Roger Swaab, Alan Taylor, Martin Taylor, Phil Taylor, Danny Thompson, Richard Thompson, Kevin Townend, Ken Townsend, Rob Townsend, Tim Tucker, Peter Van Hooke, Dave Vary, Peter Vince, Derek Wadsworth, Bernard Watkins, Charlie Watkins, June Watkins, Peter Watkins, Michael Walling, Greg Walsh, Terry Walsh, Bert Weedon, Dennis Weinrich, Bruce Welch, Chris Welch, John Wetton, Geoff Whitehorn, Ian Whitwham, Diana Wilkinson, Neal Wilkinson, John Williams, Carol Willis, Pete Willsher, Pete Wingfield, Ron Wood and Bill Worrall. x

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Out of the blue, I got a call to dep for bass guitarist Paul Westwood on Sky Star Search, a legendary TV talent show that was so appalling it was actually worth watching (they held auditions for the show, and everybody passed). The musicians in the band assembled at 8 a.m. on Sunday 12 February 1989 in London Weekend Television’s Studio Two at the South Bank Centre, and during this gruelling but hysterical twelve-hour session we supported 35 mostly abysmal acts. (Later that evening my face muscles actually hurt from laughing!)

I sat next to guitarist Vic Flick – the man who, in 1962, had played the main guitar riff on the famous James Bond movie theme. During the breaks we chatted and, having recently found some ridiculous old photographs of my school band, I was curious to know how Vic had started out as a musician. His stories, involving throat microphones and home radios, were such a revelation to me that I no longer felt quite so embarrassed about my own humble and absurd beginnings.

Almost immediately this cathartic moment triggered an idea: perhaps all of the other great players had daft stories too? The phone calls began… At first I felt like a cub reporter: phoning musician buddies may have been easy, but extracting information through artists’ management channels sometimes necessitated a certain degree of subterfuge. I was therefore delighted when so many musicians submitted their own highly literate and amusing accounts (some of these interviews first appeared in Guitarist magazine in 1989).

Roger Glover told me: “We are the last generation that can remember what life was like before rock ’n’ roll.” He was, of course, referring to a time when LSD only referred to pounds, shillings and pence, and when everywhere in England seemed to be closed on a Sunday. It was also a time when all American goods, including guitars, were totally unavailable; savants spoke in hushed tones of a revolutionary new instrument known simply as a “Fender”, although it was beyond me why anyone should want to play the mudguard of an American car or the protective surround of an open coal fire! All was revealed, however, on the sleeve of the LP The Chirping Crickets, upon which stood Buddy Holly and his chums, grey-suited and silhouetted against a blue Texan sky. In Buddy’s hand was the object that inspired such awe: the Fender Stratocaster. The first “Strat” to reach the UK was imported by Cliff Richard for Hank Marvin in 1959, and the rest is history.

Today’s guitar heroes and top session players were once mere mortals struggling to buy or build their first guitar. Much experimentation was involved, a lot of it crazy and even futile, but mostly it was just good fun. The history of xivBritish rock ’n’ roll owes a huge debt to these visionary players who produced some of the most powerful and memorable music of the last five decades. But this debt, it transpires, should also be extended to a lot of dads, a lot of red paint, a lot of radios, a lot of ukuleles, a lot of junk shops, and even a lot of tea importers.

Although I originally studied physics at the University of Sussex, I have been a studio/touring bass player for most of my life. Inevitably in the course of writing, recording, producing, and touring more than a few stories have emerged.

When I first began writing this book – almost twenty years ago, and mostly in longhand – interviews were almost always face-to-face, or one-to-one on the telephone. By the early nineties we did have fax machines, but it’s hard now to imagine that at that time Google had not been invented, there were very few mobile phones (all of which were huge), there were no websites, and only a few people – mostly women doing secretarial work – could type. There was no email, no texting, no scanning, no Facebook or MySpace or Twitter, and the internet was a concept understood by only a few scientists, the military, and specialist nerds. How that would change in the next few years!

The stories in this book chronicle the formative period during which the excitement of discovery, the naïvité, and the insane struggles gave birth to the rise and development of rock guitar in Britain, and helped to shape the way in which we perform and record today. These stories are idiosyncratic, charming, and optimistic, but above all, they are very funny.

Assembling such a rich tapestry of how it all began has been nothing short of joyous, especially as I compared others’ early experiences with my own. Whether household names, or unsung heroes, I’ve chosen the cast for their important observations and contributions to this fascinating story. I’ve heard it said that when a person dies, it is as though a library is burning down. Since I originally wrote my book, many of the contributors have sadly died, and their stories – had I not jotted them down – would have been lost forever. But the love and respect of their friends and families will ensure that their stories will live on.

The second half of British Rock Guitar is devoted to the rise and eventual demise of the London studio session scene. I’ve tried to present an insider’s view of this creative world, and the wonderful absurdity of musicians’ humour in general. As a bonus I have also learnt how to spell ukulele, bouzouki, and oud.

My 42 years as a professional musician have been far more fun than they could possibly have been had I pursued my intended career as a physicist. But I still subscribe to New Scientist magazine.

Mo Foster, Hampstead, London August 2010www.mofoster.com

FOREWORD

It seems a lifetime ago that an enthusiastic cub reporter (whom I later found out to be Mo Foster) called me up to tell me about the marvellous idea he had for a book based on the first 20 years of British rock guitar, and asked if I would contribute anything towards it. I explained that I was a bit short at the time but would send him a postal order when my next royalty cheque came in. “No, no, no,” he said. “I’m not asking for money, I’m a bass guitarist. What I need is some information, like when did you get your first guitar? What was the make? How much was it? What did it mean to you? Do you still have it… and is Elvis still working in a chip shop?”

These questions brought back to mind a particular day in 1973 when Mo (whom I have in fact known since that time and would never really mistake for a cub reporter) was rehearsing with me. I clearly remember Mo struggling with the bass part for “FBI” and thinking to myself that one day this red-headed young man with his engaging personality and blistered fingers would write the definitive – if not the only – book on early British rock guitar. And, Mo, you’ve done it.

May I take this space to thank you for the belief and tenacity you’ve shown in bringing your concept to fruition, and so enabling myself and countless others to share in the funnies and frustrations, and the hopes and aspirations of my fellow British rock guitarists. It’s a great read.

Hank B. Marvin, Perth, Australia March 2011

xvi

Mo Foster (second left) playing ‘lead descant’ with the Old Fallings Junior School recorder consort. His friend Ronald Powell (extreme left) was not to know that it would be another fifty years before his trousers would become fashionable.

PART ONE: GROWING PAINS

CHAPTER 1

IN THE BEGINNING

Houses were quiet in the early 1950s: no all-day radio stations blaring away, and until 1955 there was only one TV channel, which transmitted until 11pm and which was off the air for an hour each weekday between 6pm and 7pm so that young children could be put to bed without complaint – it was known as ‘the ‘toddler’s truce’. The 24-hour broadcasting that we know today was unheard of.

At first we didn’t own a radio, a TV, a gramophone or a piano. You could hear clocks ticking.

Until I was about nine years old I wasn’t really aware of any music at all, unless one acknowledged BBC schools’ radio programmes such as Music And Movement, in which a disembodied voice might ask us to ‘play games with our balls’ or to cavort leadenly around the room, inspired by the music of tunes like Grieg’s ‘In The Hall Of The Mountain King’. I was quite a good troll.

In the fifties there were only three national radio stations available in Britain:

The BBC Home Service (now Radio 4), which was for plays and talks.

The BBC Third Programme (now Radio 3), which was for classical music.

The BBC Light Programme (now Radio 2), which was for the more popular music of the day. My parents seemed to prefer this station, a station which seemed – to me – to play mostly pointless drivel. The only pop songs I can recall on the family radio from that time were tacky novelties. Here are a few awful examples:

“I’m a Pink Toothbrush”“How Much is that Doggie in the Window”“Shrimpboats Are a-Comin”“Two Little Men in a Flying Saucer”“Twenty Tiny Fingers”“Seven Little Girls Sitting in the Back Seat”“The Runaway Train”“The Three Billy Goats Gruff”“I Am a Mole and I Live in a Hole”“Bimbo, Bimbo, Where Ya Gonna Go-e-o”Some I could just about cope with:

“Sparky’s Magic Piano” (this was actually rather good and featured the Sonovox, an early vocoder)“Tubby The Tuba” (quite emotional in places)“I Tawt I Saw A Puddy Tat” (okay, it’s fun)“The Teddy Bears Picnic” (quite good really – nice bass-saxophone)“The Laughing Policeman” (nice tuba)This is what we had to listen to at 9 a.m. on Saturday mornings on Children’s Favourites in 1954! They certainly weren’t my favourites. It’s very weird to think back and realise that the only music that made any sense to me was hymns, which I would hear at school assembly every morning or – on special, but always bewildering occasions – at the local church. I loved the harmony and the bass-lines that were played on either the organ or the piano but I loathed the dreary singing and incomprehensible lyrics. To this day I can only be in a church as long as no one is singing.

In later years I began to envy American musicians who talked about listening to, and being influenced by, powerful local radio stations playing rock, blues, country, bluegrass, jazz, gospel, etc. Lucky bastards. For us in the UK all we had was the idiosyncratic Radio Luxembourg, and it would be a while until pioneering DJs such as Jack Jackson and Brian Matthews began broadcasting their wonderful programmes on the BBC in the early sixties. Eventually, of course, the pirate radio stations – such as Radio Caroline and Radio London – would come to the rescue.

RECORDER

One day, when I was nine, my primary school teacher, Miss Williams, brought a “descant” recorder into class, played it for a couple of minutes and asked if anyone would like to learn to play and form a recorder consort. I was mesmerised. My parents didn’t take much persuading to buy one and, having presented it to me one afternoon on a pavement somewhere in Wolverhampton, were amused that in my zeal 2to open the white cardboard box, I had read the label a little too quickly and proceeded to thank them profusely for buying me a “decent” recorder.

I became fascinated with instruments that I saw in marching bands – such as the trumpet – which had music stands shaped like lyres fixed to them. Inspired, I carefully bent a convincing music stand out of stiff wire and fixed it to the end of my recorder with Christmas Sellotape (it was white with lots of holly and berries, and the occasional robin). I was quite pleased with it, even though it was totally unstable, and the music kept falling on the floor.

After devouring tutor books I and II, I later listened to the radio with increasing interest as I picked up by ear the instrumental hits of the day, including “Cherry Pink Mambo” and “Swinging Shepherd Blues” complete with bent notes. Was this blues recorder?

SUMMER CAMP

My father was a PE teacher at a boys’ college in Tettenhall, near Wolverhampton, and every summer during the 50s we would take a succession of trains to Salcombe, in Devon, where 120 boys and seven or eight teachers with their families would spend a pleasant two weeks under canvas in a farmer’s field near a sandy bay. On particularly wet days everyone would assemble in the central marquee to be entertained with a sing-song, or by anyone with a talent for playing a musical instrument.

One boy played the accordion; he was good and had a fine repertoire of folk tunes. I was seized by the desire to accompany him in some way, but this momentary eagerness was rendered futile by the realisation that the only instrument I could play convincingly was the descant recorder, and then only from sheet music. The damp throng would certainly not be interested in hearing my unaccompanied selection from Swan Lake. Nevertheless, the seed of desire to be part of a music-making team had been planted, although for this to happen convincingly I would have to wait for the advent of rock ’n’ roll… and the guitar.

VIOLIN

A little later I was given a violin, a shiny instrument in a drab black case which had been handed down to me by my grandfather. By now I was eleven years old, the top recorder and violin player in the school. I would play violin concerts accompanied by my teacher, Miss Williams, on the piano. In my innocence I thought I was pretty good, but I was sadly deluded and, after one particular recital, I went to the back of the hall where an older man was engrossed with a machine that had two spools on top. This was the first time I had ever seen a tape recorder (there weren’t many around). Having rewound the tape, he pushed a button and I was surprised to hear the ambient sound of someone playing a violin rather badly, and with a pitching problem in the higher registers, about 100ft away. It became obvious that the offending violinist was me: I had experienced my first lesson in objectivity.

I studied violin privately for a while with a proper music teacher, Mr George Schoon at Tettenhall College, and even joined the Wolverhampton Youth Orchestra for about half an hour. But when I graduated from my primary school in Wolverhampton to the village grammar school in Brewood, Staffordshire, the long bus journeys involved meant that it was impossible to continue studying. Sadly I had to give up the violin.

In 1956 I arrived at Brewood Grammar School – where I would spend the next seven years – and discovered to my dismay that there was no music department and no orchestra; music was not even on the syllabus. In retrospect this was an unforgivable omission: we could study Latin, art, and agriculture – but not music.

The few token music lessons we did have were chaotic and pointless, and consisted of the class being cajoled into singing obscure folk melodies. I have this memory of the teacher leaning on his desk and staring into the middle distance, bored shitless as he picked his nose. Mercifully, this terrible waste of time and energy lasted no longer than a year.

CHAPTER 2

THE OUTBREAK OF SKIFFLE

“I think I was about 15. There was a big thing called skiffle. It’s a kind of American folk music, only sort of jing-jinga-jing-jinga-jing-jiggy with washboards. All the kids – you know, 15 onwards – used to have these groups, and I formed The Quarry Men at school. Then I met Paul.”

(John Lennon)

When I was 13, my schoolfriend Graham Ryall and I went cycling and youth-hostelling around North Wales. In those days there were strict rules about vacating the hostel in the morning, and as we were leaving a hostel one Saturday, I remember hearing a couple of older boys pleading with the warden to let them stay and hear the BBC radio show Skiffle Club (which became Saturday Club on 4 October 1958, and was at that time the only thing worth listening to apart from Radio Luxembourg). I had no idea what they were talking about.

Skiffle, however, was a short-lived phenomenon. Although its widespread popularity lasted only 18 months, it served both as an influential precursor to the forthcoming rock ’n’ roll craze and the catalyst behind many a British youngster’s discovery of active music-making. Like punk 20 years later, skiffle was of critical importance to British rock ’n’ roll, but was forced to endure a love/hate relationship with the music business. Inexperienced would-be musicians loved skiffle because they could at last approximate a melodic or rhythmic sound with makeshift instruments and without any real skill, but purist aficionados of “good” music detested it with a vengeance. Some journalists were wont to label the style “piffle” – and that was when they were feeling charitable.

Mike Groves

As a skiffle player, Mike Groves of seminal folk group The Spinners encountered a polite line in bureaucratic etiquette when he applied for his Musicians’ Union membership: “I was the first washboard player to join the MU. They sent a nice letter to thank me for joining but didn’t think they would be able to place a lot of work my way.” In households up and down the country, mums would be baffled by the constant disappearance of their thimbles – the washboard player’s vital tool. For Ron Wood, the instrument was simply a way of getting started in front of an audience. He says: “One day I spotted something I could really make my mark with, that took no book learning (you either had rhythm or you didn’t) – the washboard. Inspired by various American country pickers, Chris Barber, and Lonnie Donegan, my first stage appearance (aged nine, at the local cinema, the Marlborough) was playing live skiffle in a band with my brothers between two Tommy Steele films, and playing washboard made me nervous enough to want to take this experience further.”

Bruce Welch

Shadow Bruce Welch observes that, “In the early skiffle days, everything was in the key of G, with discords down at the bottom end.” This simple form of music, however, had an interesting social history. It originated during the American Depression of the 1920s, when groups of people would organise “rent parties” between themselves to help clear their mounting debts. At such get-togethers, “instruments” such as washboards, suitcases and comb and paper would be used to create an uplifting blend of blues and folk, marrying tales of farm labour with those of city materialism.

Lonnie Donegan

Similarly, the spiritual void that hung over Britain following the end of World War II was filled by this new “happy” sound, and the man who spearheaded the skiffle craze, like a rough-and-ready Pied Piper, was Anthony Lonnie Donegan. In 1952, Lonnie joined Ken Colyer’s Jazzmen, in which he played guitar and banjo, and was reunited with army colleague and double-bass player Chris Barber. Chris subsequently left and formed one of Britain’s top New Orleans-style trad jazz ensembles with Lonnie, his own Chris Barber’s Jazz Band. On recording dates, however, Lonnie was employed by Decca only as a session player. 4

The Lonnie Donegan Band. L-r Jimmy Currie, Lonnie Donegan, Nick Nicholls, Mick Ashman5

During a session in 1955 for the band’s ten-inch LP New Orleans Joy, Lonnie wanted to record “Rock Island Line”, an old Leadbelly song, but the producer was reluctant and refused to do it. The engineer agreed to stay on during a break, however, and recorded the song with just Lonnie’s vocals and guitar, double-bass, and washboard. Credited to Lonnie, the track was released as a single in February 1956, hit number eight in the UK chart and launched a nationwide skiffle boom. “Rock Island Line” also climbed to number eight in the USA, helping to boost its cumulative sales to over one million. Unfortunately, Lonnie wasn’t a contracted Decca artist and received a mere £4 session fee. (Forty years later Decca eventually agreed to pay him a royalty, but sadly for Lonnie this wasn’t backdated.) Lonnie’s response, in 1956, was to sign with rival label Pye-Nixa, and on 24 March 1960 he was the first British artist to have a single shoot straight to number one with “My Old Man’s a Dustman”. Recorded live on tour in Doncaster, the song was an adaptation of the old and arguably rude Liverpool song “My Old Man’s a Fireman on the Elder-Dempster Line”.

ALL ROADS LEAD TO LON

During my conversation with Lonnie Donegan at his Malaga home – some time before he died – we discussed the often hilarious experimentations and innovations which accompanied the non-availability of decent musical instruments in the 1950s and early 1960s, and cited Vic Flick’s use of a tank commander’s throat microphone to amplify his guitar as but one example. There follows the complete transcript of our illuminating interview:

Lonnie: “The thing about the tank commander’s throat mic was that it in fact came from me. I was the first one to do that in about 1950, and it wasn’t a tank commander’s throat mic: it was a pilot’s throat mic. The surplus stores were selling everything from the army in those days, and we used it as a contact mic. We strapped it to the front of the guitar – it was all rubber – and we played through the radio because we didn’t know anything about amplifiers. In fact, I doubt if you could have even bought one then. We certainly couldn’t have afforded one.”

Where did you buy records?

Lonnie: “In second-hand shops. We had to search very hard for any American jazz or folk music of any type whatsoever in those days, and the source of supply was principally Collett’s book and second-hand record shop in Charing Cross Road. It was in fact a communist shop, and the reason why they were stocking jazz and folk was because it was music of the people – ‘right on brother’. They used to get a fair little stack – only small stuff, I suppose, now I come to think of it; there probably wasn’t more than 20 records in the shop at any one time. We kept our eagle eyes on the shelves, you know, and any time anything came in, we grabbed it. And the manager at that time was a man named Ken Lindsay, who later became a jazz club operator in St Albans. The assistant manager was Bill Colyer, who 6was jazz trumpeter Ken Colyer’s brother. It’s a funny old world, isn’t it?”

Where did you find your first guitar, and who taught you? You’re a very good rhythm player, so someone must have shown you the right things.

Lonnie: “I got my first guitar when I was 14, which is when I had my first job, in Leadenhall Street. I was a stockbroker’s runner, and a 17-year-old clerk in the office was an enthusiastic amateur guitar player – played in dance bands, you know – and he wanted to get rid of the guitar he’d first learned on. So he set about interesting me in guitar by sitting in the little cafés at lunchtime and in coffee breaks [with great animation, Lonnie impersonates rhythm guitar sounds: ching, ching, ching!], showing me what the chords looked like, and he got me so fascinated by it all that I prevailed upon my mother to pay the 25/- (£1.25) for the guitar for my Christmas present. Eventually my mum paid some of it. It was really a Spanish guitar, and it wouldn’t tune up – I broke its machine-heads trying to get it in tune. I then went out and found a £12 cello-top guitar at a music shop in East Ham High Street. My dad funded that guitar – in fact, he loaned me the £12 so that I would pay him back at half a crown a week, which I did, right to the last penny.

“Thank you for your comments about my rhythm playing. No, the answer is I never had any proper lessons, ever. I did try in the early stages to find a teacher, but of course no guitar teacher knew anything more southern than ‘Way Down upon the Swanee River’. I didn’t want to learn the scale of C; I wanted to learn three chords so I could play blues, and none of them even knew what the blues were, so I didn’t get any lessons whatsoever. I picked it all up by ear, as you could probably tell if you had an a’poth [half penny worth] of sense!”

Could you tell me a bit about your first band, and how your music progressed into the blues?

Lonnie: “You’ve got that the wrong way around. It wasn’t the band that came first, it was blues that came first: blues, country music, folk songs, almost exclusively Afro-American folk music I heard on the BBC. They had a programme once a week on Friday evenings called Harry Parry’s Radio Rhythm Club Sextet, and they’d play a couple of records per week, which were either jazz or blues – maybe Josh White’s ‘House of the Rising Sun’, or Frank Crumett’s ‘Frankie and Johnny’, or something like that. And that’s how I started getting interested in guitar and American music. Later on came the jazz. I stumbled across a jazz club when looking for blues singer Beryl Bryden, and upon finding a jazz band – Freddie Randall’s – I was bowled over by the jazz. So the two things then went hand-in-hand together until eventually, when I came out of the army in 1950, I formed my own little jazz band called The Tony Donegan Jazz Band, in which I used to play the banjo and sing a couple of jazzy-type songs and also stand up and sing some blues things, which became known, to my everlasting regret, as skiffle. If I’d only just called it Lonnie Donegan music, I’d have made a fortune.”

This music, known perhaps unfortunately as skiffle, inspired a whole generation of young musicians to play, from The Shadows to The Beatles. It was a very important part of the process in the development of British rock.

Lonnie: “It wasn’t an important part; it was the beginning of the whole process – all roads lead to Lon. I was the first to do that. Nothing very clever in that; I just happened to be chronologically number one and all the others you have mentioned, the Eric Claptons etc, were very, very much younger than me, and so they came along as little boys to hear what Big Lonnie had started to learn. Of course, they vastly improved on it at a rapid rate. It’s much easier, of course, to improve when you’re given the example in the first place, but my whole early life was involved in evolving the example.”

It was bad enough in the 1960s to get hold of decent instruments, but what was it like when you started in the 1950s?

Lonnie: “It was a great struggle to get anything related to the guitar at all, including the guitar itself. At that time about the only guitars you could buy were the imported German cello-type guitars, like the Hofners, or some second-hand Gibsons and Epiphones, things like that – all jazz-orientated guitars. It was very rare to find a round-hole guitar. We didn’t even have Spanish guitars, let alone country and western guitars – they weren’t even dreamt of.

“The first proper country-type guitar I got was a Gibson Kalamazoo, which I found in Selmer’s in Charing Cross Road – that cost me, I think, £20 [a lot of money] – and I took that with me into the army for my National Service and took it around everywhere with me. And when I came back from National Service, having met a lot of Americans in Vienna playing country music, bluegrass, and stuff, and having pinned down my hero worship to Lonnie Johnson, who I found was playing a Martin guitar, I then stumbled across a mahogany Martin guitar on a market stall in Walthamstow for £6. It was strung up like a Hawaiian guitar – you know, with the metal bar under one end to raise the strings up. Of course, the strain of doing that had bowed the arm completely, so to all intents and purposes to look at it you’d think it was useless. Well, I bought it, took the bar out and gradually the arm resumed its proper shape, and I used that guitar for a long time.

“Strings were almost entirely unobtainable. The only ones you could get were very old pre-war strings, Black Diamond, which I found a stock of in Aldgate, in a music shop which had a very, very old stock. I used to replenish from there. And then a company called Cathedral started producing guitar strings, and we all had to switch to Cathedral ’cause they were the only ones you could get – until, of course, the pop explosion, and then everybody had guitars, and strings came pouring in from everywhere. I was given my first set of Martin strings by Josh White, when he came over to play at Chiswick Empire. Nobody knew he was a blues singer; they all thought he was a variety performer because he’d got a hit song called ‘One Meatball’ – a total 7accident, ’cause it’s an old folk song, you know, like everything else in this business – all accidents. I went to see Josh every night, and he eventually presented me with a set of Martin strings which I cherished for years before daring to use them. So that’s how things were, and stayed like that until… really about the time I hit with my records, and then everything exploded after ‘Rock Island Line in 1956.”

INSPIRATION

Tony Hicks

For many the sight of skiffle groups on television signified their first awareness of the guitar. One such person was Tony Hicks who, many years before he would rise to international fame as a key member of The Hollies, was inspired by a particular guitarist in the background of Lonnie’s band. “My sister Maureen used to buy Lonnie Donegan records. Although I liked the songs, when his group was on TV I never looked at Lonnie himself – I was always attracted to the sight and sound made by the man at the back, and this funny little box he had with a wire going to it. I initially cut out what looked like a guitar in plywood – the shape sort of appealed.”

Peter Watkins

Another similarly affected person was Peter Watkins, with whom I would later team up at school to form The Tradewinds. Peter says: “I suppose I first noticed the guitar when I saw Lonnie Donegan on what was probably the TV show Sunday Night at the London Palladium. I quickly observed that there were two distinct types of guitar: the one with the round hole and the tear-shaped black thing around it, and the one with the ornate f-shapes and knobs and things. I made both types out of cardboard – no cricket bats for me – and posed in front of the mirror. The round-hole type was the more important – the star played that one. The other sort was played by the man at the back.”

Les Bennetts

The guitarist in question, who now appears to be forever immortalised as “the man at the back”, was Les Bennetts. Les’ first guitar was made from a cigar box, a pencil case and some fuse wire, and featured just two strings. From records, his early inspirations were Les Paul, Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt, and later Wes Montgomery and Barney Kessel. Ironically, despite earning his living by playing skiffle and rock, he vehemently hated the music (“I couldn’t stand the ‘Coke bottle down the trousers’, a device some singers used that they hoped would arouse the girls in the front rows”) and deemed it “crap”. He was a jazzer, you see, but the good stuff paid no money. His band, Les Hobeaux, regularly played the 2i’s club in Old Compton Street, where there was always lots of jamming going on, and new players like Big Jim Sullivan and Hank Marvin would while away the hours watching him from a crouching position. Earlier, Les had taken a couple of lessons from guitarist Roy Plummer, who encouraged him to play melodies with two or even three strings – he reckons Hank learned that from him.

Les Bennetts, ‘the man at the back’, playing at the Earlswood Jazz festival, Birmingham, in 1963

When Les Hobeaux recorded for HMV producer Norman Newell, he had a problem with Les’ playing (“You’re playing too much jazz”), and brought in a staff guitarist: Bert Weedon!

After the 2i’s, Les toured the Moss Empire circuit alongside Tommy Steele and The Vipers. On one night his agent asked him to stand in for Lonnie Donegan, who had the ’flu. They liked him, and he later auditioned for Lonnie at the ABC Blackpool.

Skiffle Group Les Hobeaux, with Brian Gregg (standing, right) on Double Bass, and Les Bennetts (seated, centre) on lead guitar

8Les: “When do I start?”

Lonnie: “You’ve started.”

He subsequently played on and arranged all of Lonnie’s big hit singles. “Yet again, the irony of a good player playing simple music, and occasionally playing a dustbin, in order to survive,” said Les, who continued to play skiffle up until his sad death in 1996, not long after I had interviewed him.

Chas McDevitt

Another artist who became synonymous with skiffle was Chas McDevitt, who recorded “Freight Train” at Levies’ Sound Studio in Bond Street, with Nancy Whiskey on vocals. It was one of the foremost hits of the genre and a number five single in April 1957. When he was 16, Chas became very ill and was sent to a sanatorium for nine months, where he became interested in jazz and blues and began playing the ukulele. When he regained his strength he went back to college and joined a jazz band, playing mostly banjo. He took up the guitar and joined the Crane River Jazz Band (which had originally been formed by Ken Colyer), playing gigs in jazz clubs and coffee bars. Their set also featured skiffle numbers, and it wasn’t long before The Chas McDevitt Skiffle Group was formed from within the Cranes. Liberal in their musical tastes, Chas’ group epitomised all that was skiffle and drew on folk roots, blues, jazz and mainstream pop to develop their own infectious formula.

Capitalising on the success of his single with Nancy Whiskey (who was soon replaced by Shirley Douglas, one of the first female bass guitarists), in 1958 Chas founded the Soho nightclub, Freight Train. This popular venue for live music ran for ten years, during which time it was the favoured haunt of many London musos, before it eventually became a “jukebox dive”.

DISCOVERY

Many of the rock stars of the 1960s and 1970s born around the time of World War II came to develop their love of the more energetic and dynamic rock ’n’ roll through an earlier appreciation of skiffle. Deep Purple’s Roger Glover was one of several such musicians, and has a vivid memory of the time when he was “baptized” through his confrontation with a skiffle group.

The De Luxe Washboard

Roger Glover

“In 1955,” he says, “I was living above a pub that my parents managed in Earl’s Court, in London. I was nearly ten years old. No doubt to attract new custom they started getting skiffle bands to play in the saloon bar on certain nights. Picture me one night, in pyjamas, wondering what the sound was, creeping down the stairs, inching open the door that led to the bar and finding myself almost in amongst a skiffle band as they played. Revelation! Live music! There would be about five or six of them: several guitarists; a banjo or ukulele player; a percussionist, whose main instrument was a washboard with all kinds of bells, cymbals, hooters and whistles attached; and a bass player using a tea chest bass. There was a furious strumming, banging, thumping and a lot of hollering, followed by applause. Then it would start all over again. My eyes grew wide that night.

“Every night that they played I would be there, an unknown fan, peeking in on what grown-ups did and wanting to be part of it so much. Because the bass player was at the back he was the one I was closest to, and I loved that sound. It was almost magic, the way an upturned tea chest with a bit of string secured in the middle and tied to the end of a broomstick could make such a deep, driving, thumping sound. It swung so much, and all the other instruments seemed to be driven by it.

“So skiffle music became my first love. The charts were full of songs by people like Anne Shelton, Kenny Ball or Dickie Valentine, but for the first time I was aware of the existence of music other than what was in the Top Ten. I stumbled across it, and my record collection was started. The first 78 I conned my parents into getting me was ‘Cumberland Gap’ by Lonnie Donegan, and I also owned ‘Streamline Train’ by The Vipers Skiffle Group, ‘Big Man’ by The Four Preps and ‘Singing the Blues’ by Guy Mitchell. As one can see by these choices, I was either broad minded or confused. Ken Colyer and a few others were good, and I remember wanting ‘Freight Train’ but I guess we couldn’t afford it. For some reason – probably lack of the readies – these four records were the sum total of my collection for years. It wasn’t until years later, when I was doing my first summer job – mowing grass for the council – that I bought Chuck Berry’s first album.

“I didn’t like trad jazz very much, except for the fact that 9skiffle had emerged from it, but not far up Old Brompton Road was The Troubadour – a favourite hangout for beatniks with their folk music. I never went in, and subsequently it held me in thrall. I heard the music, though, and I was fascinated. The line between skiffle and folk was vague; sometimes the music was interchangeable, so I liked them both.”

Andy Summers

Andy Summers, who went on to play guitar with Zoot Money and The Police in the late 1970s and 1980s, was at one time a member of two or three skiffle groups who practiced in various mums’ and dads’ front rooms, boys’ bedrooms and church halls, and always with the admonition to “Keep it down!”.

He recalls: “Our guiding star was Lonnie Donegan, and the repertoire consisted of songs such as ‘Midnight Special’, ‘John Henry’ and ‘St James Infirmary’. The ultimate moment for me came when I was allowed to sing and play ‘Worried Man Blues’ and ‘Tom Dooley’ in front of the whole school. When I had finished my performance, there was an audible gasp from the audience. Whether it was in disbelief at the ineptitude of the performance, or horror at the ghastly American row that had just sullied the school assembly hall, one will never know. However, the result was that my status went up ten notches in the school, and I was constantly followed home by adolescent girls – my career in rock had begun!”

Andy Pyle

Meanwhile, when Andy Pyle decided to jump on board the skiffle bandwagon, his problem was not a lack of ingenuity but one of bad timing. “From an early age I’d been treated to a diet of Elvis, Little Richard, Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly, The Everlys, and Gene Vincent thundering from the radiogram, courtesy of my teenage brother and his dodgy pals. Determined to be a part of this phenomenon, I repeatedly asked my parents for a guitar. They repeatedly said no. By the time I was twelve, skiffle was all the rage, and as a couple of my friends had guitars I thought I was in with a chance. It was pointed out to me, rather cleverly, that two guitars were enough, and that the last thing needed was another one. This revelation led to my first bass, which I made one Saturday morning out of a tea chest, a broom handle and a piece of string. We ‘practised’ all that afternoon, and by tea time my fingers were bleeding, the neighbours were complaining, Mum wanted her broom handle back, and anyway the tea chest had been promised to an aunt who was emigrating.”

The Bluetones Skiffle Group, featuring Jim Rodford on tea-chest bass, playing at a St Valentine’s Day dance in a printing firm’s canteen in the mid 1950s. Jim Rodford: “That night we had the rare luxury of using the in-house public address system for vocals.” L-r Mick Rose, Jeff Davies, Jim (partially obscured by tea-chest with a broom handle), Bill Bennet and Geoff Pilling

TRANSPORT PERILS

The tea-chest bass, although a cheap and functional alternative to the expensive and technically demanding double-bass, presented a whole range of problems when it came to transporting it from gig to gig. Of course, these were the days when privately owned vehicles were still rare luxuries, and public transport was often the only option – although not all bus conductors were sympathetic.

Dave Lovelady

Dave Lovelady, of successful Merseybeat combo The Fourmost, remembers: “One conductor was very loath to take our tea-chest bass on the bus. After we pleaded with him, he agreed to let us stand it on the platform, right on the edge. As we were pulling off from the next stop a chap came running full pelt for the bus. He made a frantic leap for the platform but grabbed the broom handle instead of the pole. He went sprawling into the street and the tea-chest bass went all over the road.”

Jim Rodford

Jim Rodford, who was yet to experience acclaim as the bass player with Argent, faced similar difficulties. “The skiffle group I was in, The Bluetones, was on a double decker bus going to a youth-club gig in Hertfordshire. I was sitting on the long sideways seat at the back by the door, with my foot against the upturned tea-chest bass, with drums and broom handle inside, lodged in the well under the stairs to the top deck to stop them falling out of the bus when we drove around corners. Bus stops were very rarely anywhere near the gig, and the argument was about whose turn it was to 10carry the loaded tea chest on his shoulder, up the road to the youth club. It was always me or the drummer, but we felt it was unfair that the guitar players, with their light Spanish acoustics (no cases, not even soft), didn’t take a turn. This was the extent of our equipment: no microphones, amplifiers, PA – nothing. Just acoustic guitars, tea-chest bass, drums and washboard. It didn’t matter, because that was then the state of the art for all the emerging skiffle groups up and down the country.”

Danny Thompson

A stroke of genius from upright bass-playing legend Danny Thompson cured most of his tea-chest transport problems. He and a friend formed a skiffle group after having been inspired by the blues that they heard on Alan Lomax’s radio programme Voice of America, and Danny built a collapsible tea-chest bass (five sheets of hardboard with a bracket) which could be folded down for travel on buses. The solitary string was in fact a piano string, “borrowed” through a friend who was a tuner. Like many kids with stars in their eyes, Danny’s group entered many skiffle contests, and at the age of 14 they were singing songs that they couldn’t possibly understand, such as “Rock Me Baby”. Danny, however, didn’t sing, and admits: “I don’t even talk in tune.”

Licorice Locking playing tea-chest bass with The Vagabonds in Grantham, 1956. The secret of his sound was to use GPO string, although the tufted headstock may have contributed.

Hank Marvin

Even the sophisticated tones of The Shadows had skiffle origins, as did the music of The Beatles, in their first incarnation as The Quarrymen with Paul McCartney on lead guitar. Hank Marvin, meanwhile, was developing a passion for jazz and folk music, and taught himself to play with the aid of a chord book and many visits to a happening local jazz club called the Vieux Carré, down near the Tyne. Whereas many guitar players in later years would dream of Fenders with pointy horns and scribble them absently in their school books, Hank would draw the instruments associated with skiffle groups, such as washboards, banjos, double-basses and acoustic guitars. Hank’s own team, the Crescent City Skiffle Group, entered a skiffle contest at the Pier Pavilion in South Shields on Saturday 18 May 1957, and in spite of stiff competition, and to their great surprise, they won!

Bruce Welch

That summer, inspired by their mutual interest in music, Hank teamed up with a friend from school, Bruce Welch. Bruce had his own band, The Railroaders, who played more commercial music – the revolutionary rock ’n’ roll genre, which was then traversing the Atlantic at great speed to capture the hearts and imaginations of British skiffle lovers. He had now discovered – and indeed wanted to be – Elvis, whereas the young Hank was “more the jazz/blues purist. He wore a duffel coat with a long college scarf. Hank was a much more serious player; he played banjo with real chords!”

A year or so previously, Bruce had queued for ages at the side door of the Newcastle Empire to catch a glimpse of ‘The King Of Skiffle’, Lonnie Donegan. “I nervously handed him my autograph book, and he spoke to me. Even now, I can remember my hero’s words like it was yesterday: ‘Fuck off, son, I’m in a hurry.’ I was absolutely choked.”

What Bruce didn’t realise was that the Donegan Band were exhausted. It was Saturday night, they’d finished a week’s work, and they had to race across town to avoid missing the overnight sleeper train back to London. When you’re 15 you don’t know about such things, but Bruce has 11since learned all about tight schedules and the problems of touring. He and Lonnie later became good pals.

Hank Marvin’s schoolday scrapbook

Like all of his peers and contemporaries, Bruce learned guitar by listening intently to the artists of the day, imitated them, and then gradually added his own personality to develop a unique style. There were always areas of mystery about the records he heard: “Nobody realised that Buddy Holly used a capo on things like ’That’ll Be the Day’, so we learnt the hard way – without.” It was through manfully dealing with such struggles that Bruce later inspired a nation of rhythm guitar players. For now, though, Britain’s youth was in the grip of the second phase of its spiritual reawakening: the birth of rock ’n’ roll.

Skiffle was a blend of country music and the blues, a craze that had swept the nation. But it was soon followed in Britain by trad jazz – a sanitised version of New Orleans jazz. And as music evolved from the dance band-led fifties to the rock band-led sixties the main music paper – MelodyMaker – imperceptibly changed its content from trad jazz to pop and rock. As a consequence the front page – which once featured men with shiny brass instruments and women in bathing costumes – now featured strutting men with guitars and women in flowing costumes.

But it wasn’t until the advent of amplified instruments that the music really became exciting, made sense, and was of any interest to the new teenagers. 12

CHAPTER 3

ROCK ’N’ ROLL ’N’ RADIOS

Britain was still suffering from the aftermath of food rationing and post-war reconstruction when rock ’n’ roll hit its shores. America remained a mystery, a sprawling continent where oversized fin-tailed cars filled the streets and the people seemed larger than life. In sharp contrast to our permanently grey and uninspiring environment, America seemed to be fuelled by the Technicolor™ of Hollywood movies. It was an exciting, exotic, and impossibly distant place, the stuff of dreams.

The first artist to break into the British market with a rock ’n’ roll record was Bill Haley and his Comets, with “Rock Around The Clock” on 15 October 1955. When an identically titled film was shown for the first time in British cinemas the following year it incited unprecedented youth riots. Cinemas were literally torn apart. Parents were horrified. Bizarrely, the singer responsible for cooking up this storm was a chubby 30-year-old man with an out-of-place kiss curl. Haley looked more like a school-teacher than a rock star, and certainly not the kind of person one would associate with revolution.

Although this country perceived the birth of rock ’n’ roll to be a sudden event, in truth it had evolved slowly over the previous ten years, absorbing the flavours of jazz, R&B, country, and bluegrass, but for the first time the music was allowed to be a channel for raw emotion. Unlike Bill Haley, Elvis Presley was young, soulful and, more importantly, dangerous, seeming to sing with the voices of both God and the Devil. At first, with his smouldering, hip-swivelling movements, he was perceived as a threat to the American youth, and could only be shown on TV from the waist up. The moment when Britain began to divert its attention away from skiffle came on 19 May 1956, when the dark and sinister ambience of Elvis’ “Heartbreak Hotel” entered the chart on its way to the Top Five. To some the record was incomprehensible, particularly its lyrics, while others marvelled at this new and original sound. Nevertheless, this was only the beginning.

Judd Procter

It was around 1956 that Judd Procter felt the first tremors of rock ’n’ roll, coinciding with the publication of photographs of Elvis and Tommy Steele in Melody Maker. He and his mates thought that the rock ’n’ roll and skiffle they heard on the radio was: “A load of crap. Musos had an uncommercial view of music, and they played the stuff under duress. Where were the lovely chord changes?” Perhaps a restricted viewpoint from someone of only 22, but 30 was considered to be very old then.

Roger Glover

Roger Glover recalls what he describes as the “sudden impact” of rock ’n’ roll: “6.5 Special on TV was kind of old fashioned, or maybe that’s my memory playing tricks, but it was the only place you could see the new stars. It’s hard to imagine now but Wally Whyton, hitherto a gentle folkie, was the presenter of this rebellious new music! ‘Rock Around the Clock’ reminded me of skiffle in a way: it had the same exaggerated backbeat, and I liked that but Bill Haley’s voice and his silly hairstyle didn’t turn me on.

“Then I heard Elvis Presley: ‘Hound Dog’ did it. I strained to catch every word, every breath, every detail. I’m sure that for all of the musicians of my generation that snare drum sound is, even to this day, a benchmark. When the follow-up, ‘Jailhouse Rock’, was released, I was ready for it. I recall my friend Keith and I listening to it repeatedly for an entire afternoon. Then we’d flip it over and listen to ‘Treat Me Nice’ until bedtime. It was exhilarating stuff.”

Chris Spedding

When Chris Spedding discovered rock ’n’ roll he couldn’t wait to lose the violin and get a guitar. He observes that a 12-year-old guitar player in those days stood a better chance with the girls than a 12-year-old violinist. “My parents were aghast, and thought that guitars and rock ’n’ roll were synonymous with teenage delinquency – they were actually pretty well informed,” says Chris, “and, having just bought me an expensive violin, they weren’t about to indulge this latest fad by buying me a ‘horrid, beastly guitar’.” 14

Jeff Beck

Jeff Beck’s devotion to the electric guitar began at a very early age. “I can remember just being very impressed with the sound of the thing. Les Paul was the first player I singled out, I think, because he played the signature tune on some radio programme. My elder sister also influenced me. She listened to Radio Luxembourg. She would never say ‘Oh, I love this guy’, or ‘Elvis is great’; she would point out a guitar solo. I was most interested in bands that used the guitar to great effect, people like Scotty Moore, Cliff Gallup and Gene Vincent – all of them in the States, which is where my musical roots are.

“After Les Paul, the next important influence – and it was some time later – was ‘Hound Dog’. Not so much Elvis himself, but the guitar solos – they put me on the floor for several months. Then I started to take in what rock ’n’ roll was about: the outrage of it, hips wriggling, greased-back hair.”

John Lennon

For John Lennon rock ’n’ roll signified a major turning point as he approached adulthood. He once said: “I had no idea about doing music as a way of life until rock ’n’ roll hit me. Nothing really affected me until Elvis. That changed my life. The idea of being a rock ’n’ roll musician sort of suited my talents and mentality.”

Tom McGuinness

Lonnie Donegan and skiffle opened the door for Tom McGuinness, starting him on the ‘three-chord trick’. Buddy Holly proved to him that he could do it wearing glasses, and Hank Marvin showed him that he could wear glasses and be born in England and still play rock ’n’ roll. “Without those people I might never have become a musician,” says Tom, “but hundreds of others have contributed to making me what I am today: a guitarist still learning his trade. And I’ve only found one other thing that I enjoy as much as making music, but that usually involves being horizontal!”