28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

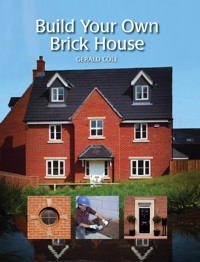

Build Your Own Brick House follows the process of a self-build, using traditional brick and block techniques, enabling the self-builder to understand both the individual stages and the nature of the build as a whole. It takes a practical approach, focusing on the best use of time, abilities and budget, and on communicating more clearly and effectively with designers and tradespeople in order to make the build as smooth as possible.The book covers:The possibilities and practicalities of building in brick; Making a budget and finding/buying a plot; Designing with brick; Obtaining planning permission and Building Regulations approval; Employing both a main contractor and subcontractors. Each stage of the build is covered, from foundations through the walls, roof, interiors and services, up to completion of a project and trouble-shooting. An essential and practical manual for the self-builder, and packed with tips and tools to help the self-builder understand the individual stages and the nature of the build as a whole. Fully illustrated with 250 colour photographs. Gerald Cole is the consulting editor of SelfBuild & Design magazine and has completed his own self-build.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 519

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Build Your Own

Build Your Own Brick House

GERALD COLE

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2013 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Gerald Cole 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 628 4

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgements

1 Why Build in Brick?

2 How to Self-Build

3 Making a Budget

4 Finding a Plot

5 Assessing and Buying a Plot

6 Obtaining Finance

7 Choosing a Design

8 Designing with Brick

9 Finding a Designer

10 Obtaining Planning Permission

11 Obtaining Building Regulations Approval

12 Hiring a Main Contractor

13 Hiring Sub-Contractors

14 Managing Your Build

15 Last-Minute Preparations

16 Groundworks

17 Ground Floor

18 Walls

19 The Roof

20 Windows, Doors and Rainwater Goods

21 First Fix

22 Plastering, Dry-Lining and Screeding

23 Second Fix

24 Completion and Snagging

Contacts

Index

Preface

If you’re looking for a definitive, or comprehensive, manual for building your own brick home, this book isn’t it; but, then, neither is any other.

House-building is simply too large, too complex and too varied an activity to be described exhaustively, even in a whole library of manuals. Just as importantly, many of the skills it demands reside not in words, technical drawings or formulae, but in the hands, memories and imaginations of the craftsmen and designers who take part.

That isn’t an excuse, by the way – rather, a cause for celebration.

Self-build – building your own home – is, after all, an extreme form of self-expression, if only because it will cost most of us the largest sum we will ever spend in one go.

This book, then, is an attempt to make that process a little simpler, easier and cheaper by following the activities it entails in, broadly, the order in which they occur. At the same time they are kept in the context of the project as a whole, taking account of what, typically, should happen next or simultaneously.

‘Typically’, of course, isn’t really a word that should be applied to something so individual in nature, but brick is Britain’s traditional building material and the skills that go into making it, and making homes out of it, are centuries old and have gathered a wealth of practical wisdom. Hopefully, this book will provide some insight into that wisdom, and enable you to appreciate some of the practicalities and possibilities of brick. At the very least, you should be able to communicate more clearly and effectively with the designers and tradespeople who will bring your dream home into reality.

The principle, then, is not so much to show you how to build a brick home, as to show you how it should be built. The approach is severely practical, with the emphasis on making the best use of your time, abilities and budget.

One thing that isn’t stressed, however, is price, except in terms of relative costs. Prices change too frequently and the degree of accuracy you will need is better found elsewhere.

Good luck with your build; though, having made the very sensible decision to read this far, I’m sure you won’t need it.

Gerald Cole is the former launch editor, and now consulting editor, of SelfBuild & Design magazine, for whom he writes a monthly column. He has completed his own self-build and numerous house and flat renovations.

Educated at Wadham College, Oxford, he has published thirteen books of both non-fiction and fiction, including the novelization of the film Gregory’s Girl.

Acknowledgements

It’s only when you are asked to write book on a subject on which you believe yourself to be knowledgeable that you discover how little you actually know. Grovelling thanks are due to the following, in particular, for their generosity, expertise and encouragement.

Bob Harris, MCIOB, 2006 Master Builder of the Year, lecturer on ecological building, building consultant and passionate advocate of high thermal mass construction. You can gain a flavour of Bob’s philosophy and achievements at www.earthdomes.co.uk.

Andrew Pinchin, architect, serial self-builder and brick aficionado, whose elegant designs and imaginative use of brickwork have embellished south-west London for many years. Andrew’s expertise is currently available through the advice pages of SelfBuild & Design magazine.

Norman Stephens, master bricklayer, builder, perfectionist and lecturer on bricklaying skills.

Thanks are also due to Hanson, Ibstoc and Wienerberger, the UK’s leading brick manufacturers, who provided both advice and numerous images of brick homes and brickwork, and to Sketch3D (www.sketch3D.co.uk) for images in Chapters 10, 11 and 17.

Photographs and diagrams contributed by other companies and individuals are credited in context.

CHAPTER 1Why Build in Brick?

Walk down virtually any modern British street and you walk down an avenue of brick. Brick is Britain’s most ubiquitous and most conspicuous building material for new homes. Even if the internal structure is timber or steel frame, chances are the outside walls will be brickwork. That’s partly because the great majority of local planning authorities prefer it that way, partly because mortgage lenders and insurers grow irrationally nervous at any hint of ‘non-standard’ construction, but mainly because that’s the way we like it.

We may coo appreciatively over the picturesque clapboard of Essex coastal cottages or the organic curves of Devonshire cob houses, but when it comes to putting down roots, most of us opt for bricks and mortar. It’s easy to see why – bricks have a solidity and a permanence matched only by concrete or stone; but stone is largely confined to areas where it occurs naturally, while concrete smacks of public works and wartime bunkers, and its appearance is not enhanced with age.

Ageing is what brick does particularly well. Over the years its colours mellow and improve, yet it needs no regular maintenance. Its strength provides exceptional protection against wind, rain, snow and flood. Its density enables it to retain the heat of the day or the cool of the night, evening out internal temperature variations. It also provides excellent sound insulation and protection against fire.

This selfbuild, from Wimbledonbased architects Andrew Pinchin Associates, combines elements of brickwork and clay tile to create a style that’s both modern and wholly traditional.

Despite all these qualities, however, brick remains breathable. Unlike timber-frame construction – brick’s main rival – the structure of the house is not contained within an air-tight, plastic vapour barrier, designed to prevent water vapour from penetrating the timber and causing it to rot. Moisture passes through brickwork, albeit slowly, contributing to a naturally comfortable and healthy interior atmosphere.

More significantly for the builder, brick is one of the easiest of building materials to use and the most forgiving. The size of individual bricks is small compared to that of an entire home. As a result, variations from plumb that would prove disastrous for a precisely calculated timber- or steel-frame building can be compensated for with relative ease.

But it’s in the look and the feel of brick where its appeal is greatest. Bricks can range in colour from bright yellow to red to dark blue, with every variation in between – sometimes within the same brick. Yet combinations of even the plainest and most common varieties can create striking effects out of all proportion to the costs involved.

Bricks can also range in texture from silky smooth to the roughness of naked rock – and here, perhaps, is where their appeal is most basic. Brick, in essence, is the clay at our feet turned to stone, the artificial acceleration of a process that occurs naturally over millions of years.

Traditional clamp fired brick-making at Ibstock’s Chailey Brickworks in the Sussex Weald, where local clays have been used since 1711.

Today most brick-making is concentrated among a small number of large manufacturers whose products are used countrywide. But less than a century ago, Britain was dotted with much smaller, brickworks using locally available clays to make bricks for local building. They produced the hard red, blue and yellow bricks of the South Wales valleys, the cream and light red bricks of Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire, and the grey and yellow bricks of London stocks. Homes built with these materials were rooted in the landscape from which they sprung. They expressed its colours and its texture, its unique character. If you’re planning a home that will look and feel ‘right’ for its location, that promises stability and permanence, is low maintenance and economical to build, brick is hard to beat.

Why Build Your Own Home?

Perhaps a more relevant question is: why not? That would certainly be the response of would-be homeowners in other European countries, as well as Australia, Japan, Canada and the United States. In Germany, for example, a common wedding gift for a son or daughter is a serviced building plot, one of a number set aside periodically by local authorities for individual home-builders.

Self-build is the major form of house-building in Germany where companies like WeberHaus and Baufritz specialize in designing and building bespoke prefabricated homes. At their factories, customers can view demonstration houses and visit permanent exhibitions, where they can choose virtually every aspect of their new home from the interior design to details of roofing, guttering and even door and window handles.

What Do We Mean by a ‘Brick’ House?

To the building trade, a traditional brick house means ‘brick and block’. In other words, it consists of an inner wall built with concrete blocks, which supports the floors and the roof, and an outer wall built from bricks. This supports the doors and windows, keeps out the wind and rain, and presents, hopefully, an attractive face to the world. The two walls are separated by a cavity, which prevents any moisture that penetrates the brickwork from reaching the interior. More recently, it’s also been used to accommodate insulation.

The blocks used in construction are essentially bricks made from cement mixed with water and aggregates. The aggregates can include sand, stone or pulverized fuel ash (PFA), a waste product from power stations. Blocks are cheaper than clay bricks and larger, the standard size being the equivalent of six bricks, making them quicker and easier to lay. They can also be used to build floors, a method known as ‘beam and block’ (seeChapter 17 for details).

Aerated or ‘aircrete’ blocks are their latest development. Because they are honeycombed with air pockets, they provide good insulation and are so light they can even form solid roofs.

Walls built entirely of brickwork fell out of favour after 1945, largely because of a post-war shortage of bricks and bricklayers.

The plot owners can do much of the building work themselves, engage their own architect and builder, or approach one of the Germany’s 100-plus catalogue house-builders. Typically, a manufacturer might have up to seventy house designs to view in a show village. Depending on the company, customers can buy a standard design, request a variation or commission a house

based on their own design.

Customers can then view displays of every aspect of their new home, from heating systems to roof tiles to door knobs and window catches – all on the same site and usually at discounted prices. By the end of the process, the new home will be planned and priced to a level of detail we would find astonishing in the UK.

In fact, the nearest British equivalent has nothing at all to do with houses; it’s how we would expect to buy a car.

SO WHY ARE THINGS SO DIFFERENT IN THE UK?

In Germany, self-build accounts for around 55 per cent of the house-building market. Speculative building by commercial developers is around 30 per cent.

In Britain the situation is reversed. Speculative developers account for around 80 per cent of the market, which is dominated by a small number of large companies. Self-build accounts for around 8 per cent, the lowest proportion in Europe.

Many of the reasons for this can be traced back to the 1930s. Before then most Britons rented their homes, but rising incomes and cheap credit fuelled a home-owning boom. Speculative house-builders rushed to meet the demand, setting a pattern that survives to this day.

Commercial builders have undoubtedly been successful at producing large numbers of homes, but it’s been at a price. Individuality has not been a hallmark of the average ‘executive’ estate. Stereotypically, buyer choice has been limited to a small variety of bathroom suite colour schemes.

More importantly, most buyers have not been satisfied. In 2009 a survey by the now defunct Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) found that 80 per cent of all new housing was regarded by its owners as mediocre or poor. The most common complaint was lack of space. With an average size of 76 square metres, new British homes are the smallest in Europe.

Serviced plots, where the developer simply provides plots with utilities in place, leaving design and construction of the house to the buyer, are common in the USA, Australia and much of Europe, though they are slowly becoming more available in the UK.

Meanwhile, a highly conservative planning system ensures a continuing shortage of building land, which keeps house prices high and gives little incentive to developers to improve their products.

As an architect once told me: ‘House-builders in the UK do not build homes; they add value to land.’ So, if you’re intent on obtaining a new house that meets all your needs from day one, is built to the highest standards and is genuinely the best value for the price you can afford, there really is only one option. It’s time to swap sides, to move from being a consumer to a producer – of your own home.

HAVE I GOT WHAT IT TAKES TO BE A SELF-BUILDER?

Little more than a decade ago most people would have regarded wealth or a building background as the main qualifications for building their own home. But today we’ve been educated by a decade of television’s Grand Designs and similar shows. We have three national monthly magazines devoted to self-build, SelfBuild & Design, Build It and Homebuilding and Renovating, a rash of annual self-build shows, even a National Self Build and Renovation Centre. Potentially the most significant development of all, however, is the government’s first recognition of self-build in its 2012 National Planning Policy Framework. For the first time, local authorities are obliged to assess local demand for self-build and include plans for meeting it in their housing policies. A small but increasing number of councils has already begun releasing land for self-build use, while, at the time of writing, central government has just nominated seven sites of public sector land for the same use. The declared aim is to double the self-build market within a decade.

Meanwhile, the building trade has woken up to the potential of self-build. Many builders’ merchants, including leading companies, now offer self-build advice and often quantity surveying services, too. Specialist mortgages are available and even specialist insurance schemes that allow home-owners to live in their existing houses until their new projects are completed.

German-style self-build may still be some way off, but building your own home has never been so easy for so many. That said, certain qualities are undoubtedly useful. If you haven’t got them already, think seriously about acquiring them.

An ability to organize If you can run a busy home, stay on top of your finances or arrange a successful social occasion, you’re halfway there.

An ability to communicate Most building professionals speak a language of their own and assume their clients are equally fluent – until you inform them otherwise and ask for explanations. Don’t be embarrassed about continuing to ask until you’re both clear what’s being agreed. It’s amazing how easily mutual misunderstandings can arise.

An ability to research An extension of the above. The more you research your project, the less likely you are to make a mistake. In self-build, preparation is all.

An ability to keep records Building professionals will only do what you ask them – and pay them – to do. Quotations and contracts are only the start of this process. Learn to keep track of every piece of paperwork and to make regular notes of every request made to those involved, and every agreement reached.

Flexibility Nothing as complex as a house-build will ever go exactly to plan. Learn to regard setbacks as opportunities for a re-think or an even better solution.

Patience Major building projects always take longer than you think. Always.

What you don’t need Unless you have a specific building skill, practical ability is not necessary. Most self-builders limit their involvement in this aspect to painting and decorating at the end of the build.

Self-Build Pros and Cons

Pros

The design of home you want.The location of your choice.A higher standard of building.Saving yourself a developer’s profit – typically 10 to 30 per cent of the value of an equivalent home.Saving yourself the VAT payable on building materials (seeChapter 24 for details).A smaller mortgage.The unique sense of achievement of building your own home and leaving something valuable behind you.Comprehensive knowledge of your house, unlike a home bought from a developer or secondhand – invaluable for maintenance, repair and any additional works in the future.Cons:

Having to cope with a new and unfamiliar environment.Competition from professional house-builders.Requirement for hard work and commitment.A degree of pressure – both on yourself and on your partner.SO WHO IS A TYPICAL SELF-BUILDER?

Very broadly, the market splits between families keen to jump a rung or two in the housing ladder and downsizers planning for retirement. Most are couples and most already own their own homes.

But the joy of self-build is that there are always exceptions, from individuals doggedly constructing a dreamhome over several years to low-wage earners with no savings and little hope of a mortgage who invest their own time and labour – ‘sweat equity’ – in a community self-build (seeChapter 6).

In other words, if you want to self-build and you’re willing to give it a try, you’re a self-builder.

CHAPTER 2 How to Self-Build

Most home-buyers are used to viewing completed homes – either show homes or those still owned by their vendors. They tend to concentrate on the look of the house, the number of bedrooms, the state of the kitchen and bathrooms. Unless there are obvious problems, such as damp smells or a sagging floor, the condition of the structure is usually left to the mortgage-providers’ surveyor. Surprisingly, given the scale of the investment, relatively few of us go to the expense of a more detailed survey from an independent surveyor. As a result, there can be surprises later on when an apparently solid wall turns out to be plasterboard or the attic space proves so full of timber supports there’s no room for storage.

In theory, self-building, rather than buying a new home, can save you the 10 to 30 per cent profit that would otherwise go to a developer, but in practice, most self-builders use this saving to create a home with a higher specification or in a more desirable location.

It’s a sign of how dependent we have become on volume producers – and how brainwashed we have been by the rising value of our homes – that we’ve either lost interest in the way they are built or we regard construction as the province of experts.

The truth is that, although house-building does demand skills, experience and, at certain points, specific expertise, the basic principles are well within the understanding of most of us.

Or they will be by the end of your build.

Adequate research is key to a successful self-build: The Building Centre in London’s Store Street houses the UK’s most comprehensive self-build bookshop, as well as a wealth of information and displays of building products and materials.

THE SEVEN STAGES OF SELF-BUILD AND HOW LONG THEY TAKE

Decide what you can afford You can do this in a spare evening.Find and buy a building plot This can take from a few months to several years, depending on the availability of land in your chosen location or locations, and your willingness to compromise. You’ll also need to make all the legal checks you would normally do for a property purchase.Choose a design Allow several weeks for working out the details with your architect or designer and then having plans drawn up. Even if you have a very clear idea of what you want, or are choosing an existing design, it will still need to be adapted to fit your plot.Obtain detailed planning permission This is dealt with by the planning department of the local authority in which your building plot lies. It is statutorily obliged to respond to applications within a set period, usually eight weeks, but it may be very busy and ask for more time. If there are objections to your design, the plans may need to be revised and re-submitted and perhaps considered by the planning committee of elected councillors. All this can take up to several months.Obtain building regulations approval Though there are alternatives, this is typically handled by the relevant local authority’s building control department. Its job is to ensure that all new buildings comply with the technical requirements of the building regulations. Allow around a month.Choose a main contractor or sub-contractors Allow at least a fortnight for builders to provide full quotations based on your plans. In practice, you should be considering builders from the design stage. Good, reliable contractors and sub-contractors are likely to be booked up several months in advance.Build your home Between 6 and 8 months is a typical build time for a traditional brick and block house, though problems, delays or an innovative or complex design can easily stretch it to twice that.Self-Build Approaches – Pros and Cons

DIY

Pros:

Minimal or zero labour costs.Maximum sense of achievement.Cons:

Much longer build-time.Only advisable for those with building skills and experience.Reasonable fitness and physical strength needed.Additional material costs to allow for errors.Exceptional commitment.Turn-Key

Pros:

Good for cash-rich and time-poor or those unable to make regular site visits, e.g. returning expatriates or self-builders building abroad.Reduced anxiety – let the professionals take the strain.Cons:

Most expensive method.Heavy dependence on professionals and their skills.Project Management – Single Contractor

Pros:

Good for those with organizational skills but limited experience of building.Single price for entire build.One point of contact for build process.Main contractor hires and manages sub-contractors.Main contractor will obtain reduced ‘trade’ prices for supplies and materials.Cons:

Reliance on one professional – firing a main contractor is hugely disruptive and finding a replacement difficult.A mark-up will be added to sub-contractors’ fees and materials.Possibility of high costs for extra work not included in the fixed price.Project Management – Several Sub-Contractors

Pros

Exercise full control over all aspects of the build.Avoid a single-contractor’s profit.Freedom to hire and fire sub-contractors of your choice.Freedom to negotiate costs of each aspect of the build.Potentially one of the most cost-effective approaches.Cons:

Heavy dependency on the organizational and management skills of you and your spouse/partner.Possibility of missing poor workmanship or bad practice that a professional would spot.Higher likelihood of errors due to inexperience.Constant pressure.High levels of stress likely on partner/family relationships.FOUR WAYS TO MANAGE YOUR PROJECT

There’s no single way to tackle a self-build, rather a spectrum of approaches based on the degree of involvement you are willing, or able, to make.

DIY Few people, including professional builders, boast all the skills a house build requires – at least, to the satisfaction of a building control inspector. Maximizing your own contribution will, of course, dramatically reduce your labour costs, but at the expense of time and personal effort. An alternative approach is to hire a main contractor to build a watertight shell, which you then fit out yourself or with the help of sub-contractors.

Turn-key Here, the entire project is handed over to a professional. Traditionally, this is an architect who creates the design, gains the necessary building consents, puts the plans out to tender, recommends a main contractor, supervises the build and hands over the keys of the completed house. Other professionals, including chartered building surveyors, quantity surveyors and design and build companies, can do the same. Unsurprisingly, it is the most expensive option.

Single main contractor An architect or designer produces an approved design, but then the build is handed over to one main contractor.

Project management Instead of hiring a main contractor, you take that role, engaging subcontractors and specialist firms to carry out the work and supervising the build yourself. Alternatively, you might hire a project manager, or project management company, to do it for you.

Most self-builds combine aspects of all four approaches. It’s worth pointing out, however, that whichever route you choose, the sheer number of decisions involved makes some degree of ‘hands on’ involvement unavoidable, which is really the point of such a personal project.

CHAPTER 3 Making a Budget

Working out how much you can spend on a selfbuild is, in principle, no different from budgeting to buy an existing property. In other words, you tot up your available funds, add the likely proceeds from the sale of your current home, deduct expenses, such as stamp duty, legal fees and moving costs, and then judge if you can afford the mortgage you need to complete the deal, assuming that you actually need one.

With this ‘ball park’ figure in mind, you then choose a property, and make an offer. If it’s accepted, that is pretty much that, barring a disappointing survey or a last-minute gazump. Your budgetary concerns now switch from acquiring your property to maintaining and holding on to it.

Self-build isn’t quite like that.

Buying a building plot may be no different from buying a house – the procedures are much the same – but that’s only the first stage of the process.

Stage two is, of course, the construction of your new home. The usual rule-of-thumb is to allow between a third and a half of the total budget for plot purchase, though in some highly desirable locations it may be considerably higher. The bulk of the rest is taken up by materials, labour and ancillary costs.

And here the complications start. Until you have detailed plans, and have had them accurately priced, your build budget can only be an approximation of the actual expenditure.

In theory, it should be possible to draw up detailed plans from the moment you have a clear idea of your new house. Equally theoretically, you should then be able to acquire a level plot on which to set your dream home, orientating it in exactly the way you’ve planned. That may happen, but don’t count on it. Most self-builders with a vision of their ideal home, but the most important factor in determining the house they actually end up with is the plot.

Plots come in all shapes and sizes, and all sorts of conditions. You may find your ideal location with your ideal view, but the area may be too small for the home you have in mind, or the ground may be steeply inclined, or the local planning department may place restrictions on size or roof height. Any of these factors can affect your plans, demanding minor or major revisions. That’s a normal, if frustrating, part of the process. The good news is that it can inspire all sorts of design improvements, which might otherwise never have occurred to you.

So how do you decide your budget?

The quick answer is that you start with your best estimate of the total costs and then refine it as you obtain further and more detailed information. But first you need to know the most expensive aspects of your budget.

NINE KEY FACTORS THAT DETERMINE BUILD COST

1. Size

Most home-owners are used to discussing house size in terms of the number of bedrooms – one reason why they, along with all rooms in new homes, have been shrinking steadily over the past 80 years. But the professionals who build those houses think in terms of square metres (m2). They are measured externally, ignoring internal walls, and the figures for each floor are added up to achieve a total floor area. A typical four-bedroom detached home, then, has a total floor area of around 150m2. A small two-bedroom bungalow will be closer to 75m2.

Having a clear idea of the size of your proposed home now allows you to calculate a price per square metre.

Luckily, there are a number of regularly updated construction industry price guides that can help you with this information. There are also a number of computer programs that do the same.

2. Build Quality

The industry price guides base their figures on average costs for standard quality building. For that, floors will be covered with sheets of chipboard, internal walls are likely to be timber studwork covered with plasterboard, and kitchen and bathroom fittings will be ‘trade’ models.

This isn’t to say these products and materials won’t be perfectly functional, but if you picture your dream home with hand-made clay roof tiles, solid oak floorboards and a designer kitchen, your budget will be significantly enlarged. For that reason, you need to gain an idea of the prices of these items as early as possible, otherwise you may have some unpleasant financial surprises, and possible disappointment, down the line.

In practice, most builds turn out to be a balance between size and specification. Deciding where the balance lies will depend on your personal wants and needs. For example, if you are building a home for retirement, it may be sensible to opt for a smaller floor plan with a high specification – for comfort, convenience and lower maintenance costs in the future.

If you are younger, with a large family – or one planned – a bigger house with a more moderate specification may be more practical. High-quality fixtures and fittings don’t always survive young children, and you’re still likely to have time, and earning capacity, to upgrade your home later, if you wish.

A common compromise, however, is simply to pick and mix, balancing, say, chipboard flooring against an eye-catching kitchen; or, more creatively, blending materials and items from a variety of sources – designer, trade, second-hand or salvaged – in a very personal, eclectic mix.

3. Building Method

Brick and block is Britain’s ‘traditional’ method of house-building, even though the technique has only been well-established for the last half-century. It does, however, mean that it’s a method known to all building professionals and its ubiquity helps to keep material costs reasonable. As a result, it tends, on balance, to be the least expensive building method, though, as in all building matters, that may vary with individual projects.

Building Industry Price Guides

An authoritative price guide is The Building Cost Information Service (BCIS) from the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (seeContacts). As well as an online rates database, BCIS publishes Wessex Price Books, which provide average price details from day rates for trades to all aspects of major building works. Similar price books include Spons, Griffiths and Laxton’s.

The data can allow for small, medium and large houses, standard, good and excellent qualities of build and adjustments for labour rates in different areas of the UK.

The main drawback of these services is their high price, aimed as they are at the professional sector. Much of their information, however, is available in build-cost calculators published in monthly self-build magazines. BCIS also offers a free online house-rebuilding calculator, intended primarily for insurance purposes.

Computer estimating software can provide detailed estimates. Some, like EstimatorXpress from HBXL or Sirca home Developer (seeContacts), are aimed specifically at self-builders. The learning curve, however, may be steep, though demonstration versions give you the opportunity to try them out.

Its main rival is timber frame. Here, the structure of the house – what supports the roof and floors – is made from a wooden framework. Invariably, though, this is then covered with an external wall, or ‘leaf’, of brick, stone or timber cladding.

Timber frame’s big advantage is that the frame is usually produced in a factory. Once it’s delivered to site, the structure of a house can then be erected very rapidly, enabling work to start on the interior sooner than with brick and block.

Timber frame’s disadvantages are that it’s more expensive and that a frame manufacturer will expect to be paid before delivery, which can account for up to 40 per cent of an entire budget – a big ask for so early in the build.

In theory, the additional cost can be recouped by a shorter build time, but the complexity of house-building means that projects are rarely completed on schedule, regardless of their building method.

The major attraction of timber-frame construction – brick and block’s main rival – is the degree of prefabrication, allowing the shell of a house to be erected swiftly. Michele Meyer

Alternatives to Brick and Block

Walls of brick and block separated by a cavity may be the UK’s most common form of house-building, but there are other methods of masonry construction you may consider.

Solid Walls

This is how brick houses were originally built, with single-leaf walls as thick as a brick is long. Doing the same today would not be permitted under the energy efficiency requirements of the building regulations, nor would it be very comfortable for the occupants.

However, solid masonry does have its advantages. For example, its density gives it a high thermal mass, which means that it can act as a kind of heat ‘battery’, storing warmth for long periods. It also means that the heat of summer takes much longer to penetrate thick masonry walls, keeping the interior cool. As a result, over the year, internal temperatures tend to be relatively even. This saves heating bills in winter and air-conditioning bills in summer. But this only works if the masonry is suitably insulated, and the most effective way to do that is on the outside. External insulation helps to lock winter warmth within the masonry, while slowing down the penetration of the sun’s heat.

To meet current building regulations, and to be cost-effective, solid walls are built with blocks, either dense concrete or, more typically, larger, more thermally efficient aircrete blocks. Because there’s only a single leaf, and no need to install cavity ties or cavity insulation, construction can be much faster, especially if ‘thin joint’ mortar systems are used (seeChapter 18 for details). Insulation is then attached to the exterior, using a variety of materials and systems. But isn’t the end result a block rather than a brick house?

Certainly, the majority of solid-walled homes tend to be rendered, but ‘brick slip’ systems are available, where brick faces are applied, rather like tiles, and, once jointed, are indistinguishable from a solid brick wall.

Solid-wall houses, built entirely out of blockwork with external insulation, can be exceptionally energy efficient; brickslips, like this, allow the exterior to appear indistinguishable from a conventional brick home.

An alternative form of masonry build: insulated concrete formworks are hollow polystyrene blocks, assembled Lego style, then filled with fresh concrete to create a permanent, highly insulated structure. ICFA

Insulating Concrete Formwork (ICF)

Here, the walls are built with hollow forms made of rigid foam insulation, which are then filled with fresh concrete. The forms, typically expanded polystyrene, can be panels, held together with steel or plastic ties, or individual blocks, which are assembled Lego-style. The end result is a solid concrete wall, sandwiched between two layers of permanent insulation. The interior can then be plastered, and the exterior usually rendered, though brick slips could also be applied.

The method achieves high levels of insulation and air-tightness and, since the initial assembly of the forms is semi-skilled, it has a particular appeal for self-builders. ICF is also used for basement construction.

Contact the Insulating Concrete Formwork Association for more details (seeContacts).

Prices of plots in remote, and often highly attractive, areas of the British Isles, like these examples from SelfBuild & Design’s Plotbrowser pages, can be remarkable bargains, but taking advantage of them will usually involve a significant change of lifestyle.

4. Location

Anyone who has glanced through the plots for sale in self-build magazines and seen the prices in remote parts of Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland is usually pleasantly surprised. But relatively few us are willing, or able, to take advantage – at least, without a significant change in lifestyle.

Unsurprisingly, plot prices follow the prices of existing property, making London, the south-east and fashionable holiday and retirement spots the most expensive areas. That said, the self-builder has options denied to the straightforward house buyer.

Problem plots, for example, which might deter a commercial developer, can offer an opportunity to an ingenious self-builder. Existing houses in poor condition may be candidates for demolition and replacement. Business or commercial premises may also have potential.

Alternatively, it may be more cost-effective to buy on the outskirts of a popular area, where prices are lower but the desired amenities are still within reach. One advantage of a less fashionable area is that labour costs may be substantially lower. Materials costs, however, are likely to be much the same in most parts of the country.

Plot prices per hectare and building costs for three-, four- and five-bedroom houses across England and Wales are available in Rightproperty’s quarterly index of custom-built homes.

A useful indication of plot prices and building costs throughout England and Wales is the quarterly Custom Home Build Index from Rightproperty available free through its website (seeContacts).

5. Personal Contribution

If you have a professional building skill – and with a brick house, bricklaying is hard to beat – you can make substantial savings on labour costs.

If you don’t, treat your DIY input carefully. Ask yourself:

Will the savings outweigh any consequent loss of income, e.g. through unpaid holiday time or work turned down?Is it likely to delay the progress of the professionals?Will it put me at physical risk?This is why painting and decorating after the professionals have finished is the most common self-builder DIY task.

Don’t forget, you already have a central and demanding role as the developer, hopefully reaping a developer’s rewards.

6. Ancillary Costs

First-time buyers are often shocked by the number of additional fees that materialize during an apparently straightforward house purchase – stamp duty, legal fees, mortgage arrangement fees, survey fee and so on. Self-build ancillaries trump those easily, and it’s important to allocate sufficient funds to deal with the extras that occur.

The most common ancillary costs are:

Architect or designer – for a comprehensive service (preparing plans, submitting them for planning approval, tendering for contractors and managing the build) expect to pay between 6 and 10 per cent of the total budget; or an hourly rate for smaller, specific services.Structural engineer – required to produce recommendations, calculations and designs for non-standard aspects of the design, including foundations. An hourly rate is normally charged for site visits, including travel time. Otherwise, charges can be per beam calculation (because structural engineers invariably work out the size and strength of supportive beams).Project manager – an individual or company can take on the architect’s traditional role of managing the build, and with similar payment arrangements.Stamp duty – due on land in the same way it is on property, and at the same rates.Planning application – the government’s online planning and building regulations’ resource, the Planning Portal (seeContacts), contains current fees for England and Wales.Building control application – traditionally this is arranged through the relevant local authority building control service, but other Approved Inspector building control services are also available.Party wall surveyor – only necessary if the excavations for your build will be close to a neighbouring property (seeChapter 9 for full details) and the neighbour objects. By law, he or she can then appoint a surveyor to ensure their property will not be damaged, and their fees will be charged to you.Quantity surveyor – a qualified professional who will draw up a ‘bill of quantities’, detailing all the materials you will need for your build and producing an accurate estimate of costs. He, or she, can also draw up a final account at the completion of the build.Utility connections – water, sewerage, electricity and gas supplies are local monopolies and connection charges reflect this. In addition, water companies in England and Wales will make an infrastructure charge of several hundred pounds each for mains water and sewerage. This doesn’t apply in Scotland or Northern Ireland where water and sewerage have not been privatized.To connect your drains to a sewer beneath a public highway, you will need a Street Works Licence from the local authority highways department in order to dig up the road. This, again, is likely to cost several hundred pounds.Where a main sewer connection isn’t possible, off-mains drainage is likely to run to several thousand pounds, depending on which system is most suitable (seeChapter 5 for details).Telecoms connection – relatively minor in cost compared to other utilities, largely because you have the option of a landline, cable, satellite dish or nothing at all (i.e. a mobile).Insurance – three types are essential: public liability, contract works or ‘all risks’ and employers’ liability, if you employ sub-contractors (seeChapter 6 for details). Lenders will require this.Warranties – cover against structural defects, usually up to 10 years after completion (seeChapter 6). Also required by lenders.Accommodation costs – only required if you plan to sell or move out of your existing home; temporary accommodation in a caravan or mobile home on site may be an economical, if not entirely comfortable, alternative.Builders’ Merchants

Many builders’ merchants, both local and national, provide specialist self-build advice. Their aim is to sign you up for a trade account, which you will need, and some offer build-cost estimating services, based on architect’s plans. Often the fee charged can be recouped from your first large order; sometimes the service is free.

7. Contingency Fund

However comprehensive your budgeting, there will inevitably be items of unexpected expense. Ten per cent of the total budget is typically put aside to cover this. More is advisable if problems are anticipated: for example, where ground conditions are known to be poor, or where the design is innovative or unconventional.

8. Interest on Borrowing

Before you take out any loan for your project, you should know full details of monthly interest payments, including early repayment charges and penalties if you default.

Some self-builders take out mortgages at a higher interest rate than they would prefer – usually because that’s all they are offered. Their plan is to switch to a lower rate once the house is completed and is a more attractive proposition to lenders.

Your budget, then, should include an allowance for additional repayments that may be necessary if your build takes longer than scheduled – which most do. The same applies, of course, to any other temporary loan, including overdrafts, bank and building society loans, and credit card debts.

9. VAT

Just when you thought your cash could head in only one direction, here’s a piece of good news. Value added tax (VAT) is charged on most products and materials used in construction – with a few exceptions we will cover later (seeChapter 24); but new house-building is zero-rated. This means that VAT is not, or should not be, charged by a main contractor or sub-contractors involved in your build, while the VAT you do pay on the great majority of construction items you buy can be reclaimed. There are only three provisos to this:

You must keep every VAT invoice you receive to prove your claim.You can only make one claim.It must be within three months of completing your build.These are a small price, however, for receiving a substantial sum at the end of your project. Typically, your reclaim can pay for carpeting, landscaping, perhaps even a garage, or it could eliminate or cut debt.

Building it into your budget from the start, perhaps to reduce your contingency fund, is tempting but inadvisable. It’s wiser to treat it as a well-deserved bonus.

Thinking About Budgeting

When we buy an existing house, we take an enormous number of things for granted. Obviously we expect it to be structurally sound, along with a functioning kitchen, toilet and bathroom. But, unless something is in clear need of repair, or the decoration truly horrific, it’s unlikely to demand swift attention. After all, once we’ve moved in, we can attend to it at our leisure.

A new build isn’t like that. Every item in every room has to be thought of in advance, selected and purchased. That includes the window frames, glazing and catches, the doors, door frames, architraves, handles and locks, the skirting, light switches and fittings, power points, central heating radiators and so on. Even in the smallest room, that can amount to an extraordinary number of items.

In a self-build those choices are up to you, and the sooner you make them – preferably when you first draw up your budget – the wider your choices will be, the fewer the financial surprises later and the smoother running your build.

You can, of course, leave them to your main contractor or sub-contractor, but in that case, you’re likely to end up with standard trade quality items, which may not be to your taste at all.

CHAPTER 4 Finding a Plot

Finding the right plot – or, indeed, any suitable building land – is the first big hurdle in self-build, and one that proves insurmountable to many. That’s understandable, but no indication of your likely experience.

There’s no escaping the fact that Britain is a relatively small country with well-established communities who are keen to maintain the status quo (often with good reason), and who are largely supported in this by planning laws. Overcoming, or bypassing, these obstacles to any significant degree usually takes the political and financial clout of large commercial developers.

But self-builders are developers, too. In fact, collectively they are the UK’s single largest group of house-builders, though they operate as individuals. As such, they have been generally regarded as rather amateur versions of small house-builders or budding property entrepreneurs. Public recognition has largely been confined to designated self-build lots in the post-World War II ‘new towns’, notably Milton Keynes, or ‘affordable’ community self-builds, usually organized by housing associations.

But in 2012 this changed. For the first time, government recognized the role of self-build in its planning policies and pledged to double the size of the market within 10 years. The government’s aim is to use self-build to kick-start a depressed house-building market.

Hopefully, this enthusiasm will survive a reviving economy and allow self-build to become as widespread and entrenched as it is in the rest of Europe. But it’s important to appreciate that, even without official support, an estimated 14,000 self-builders manage to complete their projects every year and there is absolutely no reason why you shouldn’t join them.

It’s also worth noting that recessions, like the current one, can be the best times to start a project. Any property you plan to sell may be worth less than it was during the last boom, but so will most of the plots you are considering. With work in short supply, main contractors and tradesmen may be much more inclined to negotiate charges, while frequent sales, not to mention bankruptcies, will ensure keen prices for household fixtures and fittings.

In 2012, for the first time ever, the government recognized the role of self-build in its National Planning Policy Framework.

You may be lucky enough to find the right plot very quickly – you may even own it already – but for many people, locating suitable land takes many months and even years. The key to success is not so much the availability of plots, as the way you approach the search and the criteria you set yourself.

For that reason the most useful attributes are persistence, flexibility, ingenuity, imagination and possibly a little low cunning. Get those right and luck will invariably follow.

WHERE TO FIND BUILDING LAND

Contrary to many people’s perceptions there is a great deal of land for sale in Britain at any given moment, and at reasonable prices, too. It includes single plots, fields, pastureland, woodland, forest and great swathes of open countryside. Unfortunately, the vast bulk of it is classed as countryside and not available for building, except in very limited circumstances (seeChapter 8).

For most practical purposes, then, house-building is confined to areas of cities, towns and villages defined by ‘Local Plans’. The Local Plan is a policy document, drawn up by the relevant local authority, which sets out the area in which development will be considered. It also includes details of the policies that apply to new housing. The Local Plan can be found at the local planning department’s offices or on the council’s website.

Development outside the Local Plan boundary is usually not permitted. Rare exceptions might be when a council is about to enlarge the boundary and your potential plot falls within the new area. But don’t count on that happening very often.

For this reason, the focus of your search should be plots that have planning permission, either outlined or detailed. Without that, the land is effectively pasture, and worth accordingly.

Strategies for Plot Searching

Visit your area of interest, preferably at weekends or holidays when you have time to explore. Get to know it well, not just in terms of building opportunities but as a place to live.Buy a local Ordnance Survey map: a scale of 1:1250 shows individual buildings. Look for open ground in or adjacent to residential areas.Tour the area, ideally on foot or by bicycle. Travelling by car, it’s much easier to miss things; even if you don’t, parking within a reasonable distance isn’t always possible.Take a compact digital camera or smartphone with a good camera and photograph likely plot opportunities.Check the small ads in local shops.Place ‘building plot wanted’ advertisements in local shops, newspapers, magazines and on local websites.Mention to anyone who’ll listen that you are plot searching in the area. Keep cards on you with your name, mobile phone number and/or email address, ready to hand out.House building is normally only permitted within areas defined by the local authority’s Local Plan, which is viewable in the planning department. In a small village, however, its extent can usually be clearly seen.

‘Bungalow eating’ involves buying existing houses and replacing them with something larger, though planners may restrict the size of the replacement.

WHAT IS BUILDING LAND?

An empty ‘greenfield’ plot – i.e. one that has never been built on before and has planning permission – may sound ideal, but if you confine your search to land bearing this description there are opportunities you will miss.

Plots that already have houses on them can have even more potential. For a start, planning permission is no longer a major issue since it’s already been granted for the existing property. Second, all the utilities are in place, saving a considerable amount in infrastructure charges.

The main drawback is that you are paying for a property you don’t want, and you now have the additional cost of demolition. But if that’s the only opportunity you can find in the location of your choice, it may be worth taking.

This is, of course, the principle of ‘bungalow eating’ – the developer’s trick of buying a small property on a large plot and replacing it with two or more properties, perhaps even a small ‘executive’ estate.

You don’t have to go that far, though; if you’re lucky enough to acquire a larger plot than you need, you may be able to divide it up, gain planning permission for the newly created plots and sell them off to finance your own build.

Meanwhile, you can try to reduce your initial outlay by looking for properties in poor condition, which, hopefully, will be reflected in the price. Look for estate agents’ ads offering homes ‘in need of modernization’ or ‘updating’ or ‘would suit DIYer’.

If you’re able to make a cash offer, you might also consider houses with unconventional methods of construction. Older forms of concrete or prefabrication induce deep paranoia in lenders, making mortgages hard, if not impossible, to find. Cash buyers may be the vendors’ only option and your offer can benefit from that.

Plots that have already been developed are known as ‘brownfield’ sites. As well as existing housing, they also include commercial properties, from huge former gasworks – such as the site of the O2 arena in London – to small, shop-sized premises. Many of the latter are found in residential areas. Former corner shops, small workshops, builder’s yards, scrapyards and rows of garages may be marketed as development opportunities with planning permission already in place. If not, a change of use can be applied for, though you should check with the local planning department whether this is likely to succeed before making any offer. Here, the chief drawback is site contamination. Even the least industrial pursuits can, over time, result in hazardous chemicals leaking into the ground, and decontamination may prove costly.

Not all plots, however, are recognized as such by their owners. The classic example is the large back garden with either rear or side access. This is known as ‘garden grabbing’ to those who disapprove. In this case it will be up to you to approach the owner, persuade them to sell and sell to you.

Rows of garages in residential areas are sometimes sold off with planning permission for a new house or houses.

Usefully, you can apply for planning permission on land you don’t actually own, though you are obliged to inform the owner. It’s also essential to reach a legal agreement beforehand. This involves either exchanging contracts (just as in a house sale) ‘subject to receipt of satisfactory planning consent’, or agreeing an ‘option to purchase’, which obliges the owner to sell only to you for a specified time. Once planning permission is granted, it’s attached to the plot, not to the applicant. Without safeguards there would be nothing to stop a grateful owner deciding to sell to a higher bidder.

All this becomes irrelevant, of course, if the garden happens to belong to your existing home.

Other potential plots include gaps between terraced houses and waste ground of any kind in residential areas. If the ownership isn’t immediately obvious, you may to able to track the owner down by asking locally or consulting the local electoral roll or the Land Registry (seeContacts).

An extended garden with good road access can be a good prospect for a building plot.

WHERE TO START

Estate Agents

Estate agents sell land as well as property, but, unless they have a specific land sale department, only a handful of plots are likely to be marketed every year.

Nevertheless, agents are keen to discover development opportunities, largely because they can produce at least two sets of commission, one for the site and another for the new property, or properties, built on it. In fact, agents have been known to contact developers they know as soon as they hear of such opportunities, enabling them to negotiate mutually advantageous deals before the property even reaches the market.

If this only confirms your low opinion of estate agents, think again. You are now a developer. You may only be developing one plot, but the estate agents you register with don’t need to know that. They do, however, need o know that you are a player, i.e. you are in the market to buy as soon as the right opportunity arises. So meet them in person, talk knowledgeably about the kind of property you plan to build, leave full contact details, follow up with a letter or email confirming your interest and call them regularly to discuss current or upcoming prospects.

Remember, most people tend to do favours for people they know and like or, at least, respect. Who knows – you may be tempted to build again, and again. This could be the start of a lucrative friendship.

Partly because most estate agents seldom deal with land sales, and partly because such sales are offered first to commercial developers, boards like this are comparatively rare.

Auctions

Auctions have traditionally been the marketplace for ‘problem’ properties. Typically, they are houses in poor condition or in need of major repair, repossessions, probate sales and so on. All these, of course, may be good development opportunities.

Land also appears regularly, and with similar variations. A recent London auction, for example, included a plot with a partially completed house that had breached building control regulations and a double plot with lapsed planning permission for two four-bedroom houses.

Each auction item is given a guide price, usually designed to stimulate interest rather than reflect an acceptable purchase figure. The vendor, meanwhile, will have a reserve price, which will not be disclosed. This is the minimum amount he or she is prepared to accept.

Auctions provide good plot opportunities, not just in terms of building land, but also for sites, like this former car showroom, which can be converted to residential use.

Auctions are designed for quick sales, with the fall of the hammer marking a legally binding contract. You may only have a week or two beforehand to visit the plot you have in mind, initiate legal searches, commission any surveys and arrange the finance. If your bid is successful, a 10 per cent deposit has to be paid immediately and the rest within 28 days. If you can’t raise it, you risk being sued for the full amount, plus compensation.

Some auctioneers, however, run conditional auctions. In return for a non-refundable deposit, successful bidders are allowed up to 28 days to obtain finance and another 28 days to complete.

The whole process can sound very hairy, with the possibility of losing substantial sums if your bid fails, but it’s not all as black and white as it seems.

If an item fails to reach its reserve price, it is withdrawn. But, if you’re still interested, you can inform the auctioneer and it may be possible to negotiate a price with the vendor. Alternatively, you can make an offer before the auction takes place.