6,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: BooxAi

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

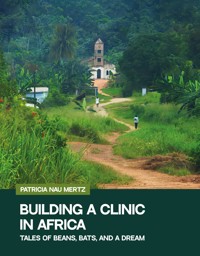

Escape to the vibrant landscapes of a remote rural village in West Africa's Ivory Coast, where the mystical génies intertwine with everyday life. In this vividly portrayed village, modern amenities are scarce, and survival depends on gathering wood, fetching water from wells, and tending to fields with nothing more than a trusty machete. Imagine mothers, and babies strapped to their backs, toiling under the sweltering sun, as they strive to nourish their families and overcome the challenges that arise. Amidst this enchanting yet demanding environment, join me on an extraordinary life-altering journey. At 56, after raising two sons as a divorced mother, caring for my loving, larger-than-life parents, and leaving behind a comfortable job at Goldman Sachs in Chicago, I answered the Peace Corps call to serve in this humble village. For 17 months, I embraced the rhythm of a different land, until political turbulence forced our evacuation in the midst of an attempted coup. Beneath the overarching ambition of fulfilling the dream of the village Chief, I delve into the intricate tapestry of this unique place while striving to adapt to the climate and appreciate the unfamiliar local cuisine despite my rebellious stomach. I learn to understand the intricacies of its colorful culture and the remarkable characters that inhabit it and witness firsthand the clash of tradition and progress as I embark on a quest to bring desired healthcare to the village. This captivating memoir invites you to immerse yourself in a world where personal transformation, determination in the face of betrayal, resilience, and the pursuit of purpose intertwine with the rhythm of a community on the edge of change.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Building a Clinic in Africa

Tales of Beans, Bats, and a Dream

Patricia Nau Mertz

Patricia Nau Mertz

Building a Clinic in Africa

Tales of Beans, Bats and a Dream

All rights reserved

Copyright ©️ 2023 by Patricia Nau Mertz

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Published by Spines

ISBN: 978-965-578-085-7

This book is dedicated not only to Chas and Kevin who have aided me in times of need, but everyone who has ever supported Ivory Coast Mothers and Children (www.IvoryCoastAid.org).

Thank you. Your kindness has touched me and so many more.

It was nearing 10 PM, as I was settling into my cozy bed with an old yellowed, musty, smelling Jane Austen book, and out came the same screeching heavy metal audio tape from across the way that would play on a continuous loop until almost daybreak.

* * *

“I am losing it!” “I… am… losing it!”

I tossed and turned. Never a fan of loud, heavy metal American rock music with its distorted, aggressive electric guitar melodies, but when combined with a techno-West African-disco interpretation all day, at full volume, on bad speakers until after 2 AM, it was pure torture.

The bangi bar that didn’t have a name owned only 3 audio tapes to play on their off-brand boom box. The proud new owners started playing the same tunes sometimes as early as 7:30 AM. Their very limited playlist began with a popular upbeat Ivorian medley that was classic, followed by a Bob Marley hit, “This is my message to you… Everything’s gonna be alright.” I hung on to the reggae message with deep conviction because I needed to believe that one day, everything would be alright.

“Why couldn’t they just play more Bob Marley or even more old Ivorian songs?” I groaned to myself. “And turn the damn thing down!”

My patience had run out. I had reached my limit. I lost it. The worst of the worst heavy metal songs was painfully piercing my frontal lobes once again, and I could not restrain myself for one more second. I burst out from under my green tucked-in mosquito net. In my bedhead, nightgown, and flip-flops, I stomped across the room and slammed open the front door. At that moment, I was face to face with a giant python that was coiled up on the concrete ledge of the front steps, and then I looked directly into his eyes and said, “You, motherfucker, are just going to have to wait a minute.”

I stormed across the way towards the drunk men gathered on the long benches with their oversized speakers and cups made from a coconut filled with bangi to kindly ask them how long they were planning on carrying on. One of them dismissed me by blurting out, “When we run out of bangi, of course.” I could hear the snickering in the background.

They were startled to see the sight of me, it was clear, and they did not want to hear any of my complaints to interrupt their soirée. I am fully aware that nobody wants to hear a command to put an end to a good party. I know. I am sometimes lovingly referred to as “Party Pat”, but not in Africa. It was obvious, I was a persona non grata. I swiftly turned around and marched back towards my house, and then screamed at the top of my lungs for all to hear the battle cry, “Seeeer pent! Serpent!”

Within 45 seconds, my courtyard was overrun with men and boys fully equipped with their weapons of large sticks and stones. They beat the python to a pulp.

“Overkill! That’s what is meant by overkill.” The snake represents everything evil and is the unwelcome devil to the villagers. It was a grand victory for me that there was no more of their music that night, and in fact, they never again met outside my bedroom window, thanks to an exaggerated story I told the chief of the village the following day. I let him know about my invitation to live in a neighboring village where there is peace and quiet.

“Patricia, viens habiter chez nous,” Come and live with us, I remembered someone half-jokingly say to me during a casual conversation.

It was true that I was invited to live in another village, but it was never a formal invitation by any means. Frankly, I didn’t care how it happened. I told the chief, and the outcome was that the very next night, he ordered the revelers to move their business away from me to the other end of the small rural village.

“Merci beaucoup, Chef!”

What a relief it was to snuggle in my bed once again with my old, borrowed book, and with a renewed sense of calm.

When the group of young men initially played their music early one evening to launch their new bangi business, I dropped in to congratulate them and to wish them luck. Crudely made benches formed a big square around a pair of mega speakers that drowned out any attempt for conversation. The bar was made of bamboo sticks and palm fronds for the roof gathered from the surrounding bamboo forest. The men were anxious to share a glass of their milky-looking palm wine poured into a rounded wood-like cup. They grinned from ear to ear about the possibilities of making some money in the impoverished village.

The day after my neighborly visit to the bangi bar, the pious elderly chief of the village called me over to his house through one of his lackeys.

“Mme. Patricia, Il ne faut pas y aller!” He made it very clear to me that I was never allowed to go there again. “You are a woman, and you are sending out the wrong message to the community.” He gave me an order.

Why would my having a drink with some young men be outlawed? This is not good, I thought. How was I going to adapt to such an antiquated culture? I had many doubts that I would ever adjust to their norms. And how was I supposed to get to know the men? Since the chief was the last word, I agreed to follow his command, at least in the village. After all, I was their guest as a Peace Corps volunteer. Their rules and their lives were much different than living in downtown Chicago.

Changes

Something wasn’t right with me. A wave of restless anxiety was controlling my morning. It was my day off work as I sat at the counter in my recently remodeled "Euro" kitchen with views down Astor, a beautiful tree-lined street in the Gold Coast near the lake. I was itching for something, and I didn’t know what. I had a plum job, planning dinners and outings for the pampered employees and clients at Goldman Sachs, and making the most money ever with lots of perks, even though some of the prima-donnas were often difficult to impress. I started thinking how my work routine was always in search of “the best,” “the finest, “and “perfect” because for an event planner or a concierge, that is the job description. I continually reminded myself of the credo to always “go above and beyond and to exceed expectations”. But I wondered how anything could really ever be good enough for them.

Perusing the local newspaper "The Reader" out of boredom, I spotted an ad that said, "The toughest job you'll ever love. Join the Peace Corps.” The sentence hit me on the head like a hammer, along with the sudden realization that I could finally do whatever I wanted in my life and maybe find work that would be more worthwhile.

Long time divorced, I had recently lost both of my beloved parents after long illnesses. My sons, Mike and Matt, in their 20s, had graduated from the university, were employed in the city, living on their own, and fully immersed in their new exciting young lives. At that very moment, I dialed the number of the Peace Corps Chicago office and set up an interview scheduled for the next day.

“Is there anything you need to know right now that would help you decide if the Peace Corps would be the right choice for you?” the Chicago manager inquired as I sat squirming on the chair facing him.

I meekly responded, "I would really need water."

He didn’t flinch, "Yes, uh huh, we all need water."

Since that was probably one of the dumbest responses he had ever heard in an interview, I was sure that I had blown any chance of them ever calling me back. To my surprise, my acceptance letter arrived a few months later, but it said that I needed to wait a full year because I was still grieving my father's death. I was overjoyed at the prospect of a real adventure of consequence and was bubbling over to tell the world, or at least my close friends and family.

“What??? You are 55 years old! You have never even been camping before, and you want to live in a developing country for 2 years and 3 months? In Sub-Saharan Africa? Are you crazy?”

Similar remarks were coming in from every corner. Most did not believe that I was serious and regarded the idea as one of my pipe dreams because I was “accustomed to the comforts of life.” Since both of my sons also have a sense of adventure, I was relieved that my Peace Corps idea, at least, appealed to them.

If it was true that I was a “late bloomer,” as it was said of me over 35 years ago in my Delta Gamma pledge class, then I had some serious blooming and growing to do, I decided. I wanted a challenge to ignite my soul and shake up my being. I felt a sense of urgency.

The big departure day was drawing near. There was an inch-thick booklet sent to me from the Peace Corps office in Washington that had been staring me in the face for over three months and was to be read in full before my journey.

On a sunny Saturday morning, feeling the pressure to complete the task, I walked over to my favorite outdoor corner coffee shop to hunker down and dig into the details about what the future would hold for me. I was making good progress flipping through the pages until I came upon the chapter "Safety and Security" when a majestic red-orange and black Monarch butterfly fluttered over and landed at the top of the page on those exact written words, “Safety and Security”.

My eyes filled with tears, recalling one of my mother’s favorite refrains to me, "Patsy, keep your wits about you." I have a propensity for mind wandering, day dreaming and bumping into things, I admit.

When the message fully resonated, the butterfly flew away. I received the warning loud and clear and left the café with a strong sense of foreboding.

There was a long to-do list glaring at me that included, “Find a renter for my condo, pack it up for rental, take its contents to a storage unit, pack a suitcase with the suggested outdoor lifestyle-type items including modest looking long skirts, go shopping (I owned no clothing fitting their descriptions and never owned a backpack or water bottle).” I had already given my 2 weeks’ notice and felt paralyzed at the thought of what seemed like herculean tasks ahead.

I could not call any friends or family because I pretended to have everything under control and wanted to avoid hearing any more negative comments. My solution was to call my childhood friend, Sara, who always responded in a calm manner whenever I was frazzled.

“Help! I need to talk this through.”

She listened and surprised me by almost immediately packing her bag and flying halfway across the country, leaving her flourishing toy and gift shop in Maine to help me attack the dreaded list. She rented a 4x4 at the airport and drove around to help run errands. We packed boxes along with countless other tasks while I made up the piles for trash, storage and donations. We worked together tirelessly into the wee hours, checking off the list with music blaring and making it fun like we always did since we were kids jumping on the beds.

The truth was that I was terrified to go to Africa and to leave the luxury and comfort of my home and my classy job at Goldman. I was brimming with self-doubt regarding my knowledge of French, fears about my bad, delicate stomach, and my general ability to succeed in my work as a volunteer with all the young 20-something over-achievers.

My designer friend said that I would be sleeping with snakes under my bed, which gave me nightmares and brought up scary childhood memories of how my older sister tormented me about snakes lurking on the bedroom floor, always in a ready position to bite my feet off. I was afraid of the unknown, but I had resolved to go and embrace my fear, my insecurities, and the idea of snakes. Most importantly, I resolved to keep “my wits about me.”

I was born on Eleanor Roosevelt’s birthday, October 11. Eleanor’s words, “You gain strength, courage, and confidence by every experience in which you stop to look fear in the face.” The anxiety that I was experiencing was part of the process, and I kept her wise words close to me.

My sons and family threw me the most memorable going away party that I could ever imagine at my son, Michael's townhouse. It was rowdy and wild, with music playing on all three floors, full-tilt skits poking good fun at me, and a medley of songs and guitars from the talented cousins.

When the Chicago Police came knocking on the door responding to the neighbors' complaints, I invited them in and gave them a tour of his place. To my amazement, a while later, they were still there hanging out on the couches, chatting up the crowd.

It rained in torrents that night, but it did not stop the many merrymakers from coming out to say goodbye. I finally felt the votes of confidence from my family and friends that I wanted and needed. The party was the perfect tonic. As my mother used to say when something was wonderful, “Lock it in your heart.”

The evening before I left, my younger brother Nick, my all-time favorite childhood, adventurous playmate, took me out for dinner and the movie, “Moulin Rouge” which became my favorite film. I was, at last, bursting at the seams with anticipation and finally ready for the unknown.

After the exhausting plane ride to the Ivory Coast via a night in Philadelphia with the new volunteers, and a week of non-stop cultural indoctrination meetings at a farm for nuns outside the capital city, Abidjan, I was relieved to finally be alone. I shut my bedroom door with my new host family who warmly welcomed me to begin our three months of training in Alépé. I collapsed on my thin foam mattress, feeling the wooden planks below in the scrubbed-clean room. The walls were painted Smurf blue many years before but were dismally stained from wear. It was furnished with one straight wooden chair and a simple matching table placed under the window with bars on it looking out at another concrete dwelling. During those first quiet moments alone, I wallowed in more self-doubt and spilled a bucket of tears into my pillow but immediately composed myself when I heard a knock on the door.

Madame called my name, “Pa tree see a viens.” I was told to come out because someone was there bearing a gift.

Ok, “Tout de suite.”

I wiped off my face, practiced a smile, and obediently went to the main room where the whole family had gathered. Standing outside the front door was a kind-looking elderly man with a dirty well-worn grey cloth bag slung over his shoulder. I had trouble understanding what he was saying. He stepped inside and dumped the contents of his bag on the floor in front of me. It was loaded with six giant, flattened, dead rat-like creatures called agouti, their most desired bush meat.

“Noooo!” I cried since I fear rats and had never seen or heard of agouti before, dead or alive. Oops, I must have missed that part of the food presentation at the nunnery when we arrived for the indoctrination. Flight was my only reaction. I escaped to my room and shut the door amid a chorus of laughter.

“Oh my God, I will never make it here,” I moaned while trying to erase the disturbing image ingrained in my mind.

I was not polite in refusing his gift. I was admonished and later apologized to the family.

During that same first night, I woke up looking for the bathroom with my flashlight and was startled to see my new family in the main room on the floor laid out in rows sleeping on their mats. I didn’t realize that it was the norm to sleep on the floor, and to think that I was hogging up a whole room!

We all arrived in the bustling town of Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa, ready for classes on health, safety, language, customs, traditions, and in my selected work, education. I slowly began to assimilate into my host family, the group of twenty exuberant and exceptional young volunteers, and the enthusiastic and brilliant Ivorian, English-speaking trainers.

It was hot and humid at the bustling market on the way to class. My senses were assaulted with smells of earthiness, spiced foods, and wood smoke. There were mounds of charcoal being sold everywhere for the women to cook their food, along with an array of unfamiliar, unpackaged spices and mounds of colorful vegetables. There were curious sounds of chattering of women wearing vibrant colors in unfamiliar patterns speaking loudly as they bartered in a strange language.

Chinese cheap housewares and tools brought in from the capital were set up on stands next to piles of bright-colored fabrics neatly folded called “pagne” that were the staple used for everything from clothing to diapers. The raw meat, which was available to those who could afford it, was hanging in full view with hungry flies feverishly buzzing around. Roaming goats, sheep, and dogs shared the sunken, cracked, and broken sidewalks. I quickly learned to keep my eyes fixed on the ground to avoid piles of excrement left by the wandering animals and avoid stubbing my sandaled toe on the crumbling ground while taking it all in.

The first time I walked to class, I crossed paths with a baby chicken. There was hell to pay for that misstep, when the mother appeared, and began attacking me with her angry beak. I was grateful that a young child had accompanied me and warded her off.

The night before, a goat gave birth outside my window. I hurled myself out of bed after hearing all the commotion to see a newborn baby goat screaming and jump-dancing around with the cord still on it. The mother just stared at it. So, needless to say, I was a bit jittery.

I settled into my unfamiliar surroundings with full-blown menopause, complete with night sweats and mood swings, strange skin rashes, and accelerated digestion problems, along with the oversized bugs, the towering vegetation, and the very kind people. Everything was new which called for major adjustments in my psyche. It was overwhelming and transformative. I thought that I might just have to slow down a bit which forced me to be in the moment.

To begin each day during the training, the lively volunteers shared their own personal experiences in adapting to the new culture with their assigned families. The process became a type of group therapy for support and encouragement. We all had a tale or two to tell during training.

One volunteer, Mike, quipped, “I think I ate the cat for dinner last night.”

Another young woman, Laura, arrived crying almost every day out of control, “I just can’t cope with anything! I want to get out of here!” She wound up staying and learned French and flourished.

A couple of other people left for home in the States before I ever knew their names.

One of my “shares” was that I was highly anticipating my first green salad after living there for almost two months, but discovered that everyone’s idea of a salad is not quite the same as my own. Madame was preparing my evening meal as I sat on a low stool outside to watch her while taking the opportunity to practice my French in conversation with her. Sitting near the open fire also on a low stool, she skillfully wielded a large machete-type knife and peeled the cucumber and carrots in her hand without a cutting board. Afterward, she carefully washed the delicate fresh lettuce in a bucket filled with a bleach/water solution. I learned that she and other host mothers were trained to prepare food hygienically for the American guest volunteers to help prevent illnesses.

I could hear the sizzling oil in a big black pot on the fire, and I assumed that it was for a meal for her come-and-go ne’er-do-well husband. I had already stood up to retreat towards the dinner table at her suggestion when I looked over my shoulder. Madame began pouring the entire contents of the pot of boiling oil that was filled with kidneys from I don’t know what kind of animal, over my beautiful, formerly crisp, fresh, green garden salad.

“Noooooooo,” I couldn’t suppress my disappointment.

Madame woke up at 3 AM most mornings to carry her attiéké that she spent days preparing by peeling the tough skin from the cassava (manioc), grating, cooking, and fermenting it, bagging it, and then traveling hours to the market in Abidjan and finally, selling it for less than fifty cents. She never stopped working like most of the other women I met. I grew to respect her work ethic and how she lovingly and cheerfully cared for her young children, and for me.

She fed her husband first when he was home along with any other male guest. The children were in the next round. And then she sat with me to eat her meal. It was the only time I ever saw her when she wasn’t preparing, cleaning, caring for the children or working on her attiéké. She wanted to know about my family and about my life and I wanted to hear about her. How I struggled to understand the African French!

After three months of training 5-1/2 long days a week was completed, we were finally prepared to meet the people in our newly assigned villages and begin our work. Our wonderful Peace Corps Country Director, Marty, had a highly trained staff who matched each one of us with a new site that would fit the needs and requests of both the village and the volunteer. We were all anxious to live on our own and find out where each one of us would be located.

The announcements were read during a ceremony when we all dressed in African garb and were individually given a small piece of paper with the population and village description, including information on where to find the closest market. I had expressed a desire for an indoor toilet because of my own personal issues. When the news broke that I received one, everybody cheered because while training, the volunteers heard my continual complaints about my never-ending stomach challenges.

It was announced officially, “Patricia to Braffouéby!”

Braffouéby

I smiled the moment I walked in to see my own freshly painted, still-wet Smurf-blue-colored house where I would live for the next two years. It was, in fact, the only color of paint available besides white. I was pleased that they made such an effort for me, but puzzled as to why they asked me what color I wanted the rooms to be painted. My ill-considered response was “butter yellow.”

My large and fine cement house was in the oldest and busiest part of the village on the main road, with clean cement floors, a separate bedroom, a kitchen area, and a toilet. I was warned that the water rarely came out of the faucet, and we were instructed to boil and filter whatever water we drank, whether from the well or the sink. Electricity worked on some days.

For the bucket baths and flushing and drinking, Odette, my dear neighbor, delivered a fresh pail of water from the well every day to my door in case the faucet was dry. We were all given a large contraption that double filtered the water to prevent worms. I had water, as promised, and I treasured the electricity. I learned to use the light judicially because of the flurry of bugs that were instantly attracted to the light.

Odette’s husband descended from one of the five founding families of the village, Ablo Bosso, and the family owned the house where I was staying. Félix Houphouët-Boigny himself slept in the same house for a couple of nights in the 1980s. He was the first President of the Ivory Coast, where he ruled for twenty years. He gifted the impoverished village of Braffouéby with electricity as an expression of his gratitude, but hardly anyone could afford to buy kerosene for their lamps, much less pay an expensive bill for electricity.

My favorite place was an elevated little patio outside the door with enough room for chairs and a table and a view of our spacious horseshoe-shaped courtyard. There was one old hut that faced a house on the other side made of cement bricks that belonged to Odette and her husband. They also have a large open-air shelter used as a traditional outside kitchen made of bamboo sticks and a palm-leaf thatched roof. Wooden chairs and benches were lined up around her area where she builds fires to cook meals and make her attiéké for sale. It is also used as the place where her friends stop in to chat and help her out with the work. Like the other women in the village, I would hear the daily sounds of her pounding the cassava with a giant mortar and pestle to prepare foutou, the traditional mid-day favorite.

Figure 1 Making attiéke

Figure 2 My New Handmade Furniture

Figure 3 A cup of bangi palm wine in a coconut cup

A graceful giant Ficus tree with spectacular, glossy, green leaves stood next to my house like an expansive umbrella to give much-needed shade. It was rare to have a tree around a house because the community used their machetes to keep vegetation cut low to prevent the dreaded snakes. It was a stunning tree and one of my favorite things about the village and my home. I was crushed to learn that they cut it down years later.

“Pourquoi?” I asked why already knowing the answer.

“Serpents!” the neighbor said with a snarl shaking her head.

Next to my house lived a very old woman in a square hut made of natural materials, bamboo sticks, and mud. She had to be in her 80s and in very frail health. It was dark inside, where her belongings were stacked neatly along the walls, and her sleeping mat rolled up near the door. Her family lived elsewhere, which was unusual because families, as a rule, lived together. I never understood much about her. After she passed away years later, the hut collapsed into a heap of debris and remained there for years like a monument to her memory.

“Patricia, attention!” my neighbor, Odette, warned me one afternoon during my first weeks in the village.

“Look over there! She is the witch who cast a spell on the man who just died across the way from you. Stay away from her!”

Sorcery was intertwined in almost every story about health, death, or wealth. People don’t openly speak of it to me anymore like they did 20 years ago, but it will forever be at the base of their culture. If someone was sick, the family member would blame the person who they believed cast the evil spell. There was little interest in finding out how someone had died or what kind of illness they had since most never went to a hospital to receive a professional diagnosis. Being sick was often a death sentence. Science didn’t seem to exist. I remember inquiring about the cause of death multiple times because of the numerous funerals that I attended of people young and old.

I was usually warned, “It doesn’t matter how the person died. The fact remains, he is dead!” I was instructed instead to ask, “Who do you think cast the fateful spell?”

The toll from extreme poverty and corruption is heartbreaking because it affects people’s futures. 75% of Ivorian rural women live below the poverty line. Poor health and education, along with the continued lack of economic development, hampers the future of the children. Malnutrition and anemia weaken them from learning at school and eventually being able to work. All these factors and more perpetuate the cycle of poverty.

“How will I ever be able to make my mark here when I don’t know where to start, much less communicate with anyone? Do I have what it takes? I can’t do this. How do I begin? Is it too late to leave? I need to find a way.” I began to spiral into a deep despair. Writing letters was my therapy. Reading was my escape.

One morning little Beatrice knocked on my door, and with her big winning smile, she said, “Bonjour, Madame.”

At first, the young children would only observe me from afar, but one by one, they became my new best friends, my sweetest light, and my source of joy. They eagerly shared with me their hopes and dreams which I always encouraged them to do. I had friends!

On my first day working in the schools, I left early in the morning to meet my supervisor at a nearby school. He revealed he had just started his new position.

“Bienvenue, Patricia!” He warmly welcomed me and then began, “The former director was recently given a large sum of money from the government to repair some of the dilapidated schools with dirt floors, leaking roofs, and broken desks. The money has disappeared, and so has he. I am now your new Director.”

The sum must have been too much temptation for him since he probably never saw or held that much money in his hands at one time. He absconded with all of it. He left his job and his family and his village, and he was nowhere to be found. He ruined his name forever and would never again be able to return home.

After hearing the dreadful news, my new Director gave me my assignment, which was to travel to five different villages for a total of 11 schools, and asked me to report to him every Friday with my lesson plans and description of my progress at each of them. Somehow, I was under the impression that I would work at the school in my assigned village of Braffouéby and not be spread quite so thinly. The task was daunting. I didn’t know my way around, and I have a knack for getting lost because of my poor sense of direction. The rural red dirt roads are lined with bamboo and palm trees, and all looked the same to me. With no street names or addresses, at first, I struggled to meet the challenges.

None of the schools had working toilets. Sometimes I would be caught somewhere walking along a wretched road through the thick forests with no place to hide during a monsoon rain en route to the next village or find myself struggling to make it home before my lower intestine exploded.

To add a another layer to my insecurities, African French mixed with their local language is not the same as the French I learned in college or in training, and there were a multitude of elders, parents, teachers, and children in each village to keep straight with all of their cultural idiosyncrasies. My mantra became, “Do my best, be prepared, and show up.”

The undeveloped infrastructure was alarming. The narrow rough red clay roads surrounding the villages were treacherous, and I hardly ever saw any cars traveling on them. And when I did, I would often see men and boys gathered to push some car out of a rut. Some of the holes in the roads were so deep that people would fill them with rags so that a possible car could pass over or be pushed out of the rut. The scenario reminded me of some crazy video game that my sons played. A rare driver or taxi was forced to turn the steering wheel sharply in one direction and then abruptly in the other direction to avoid the trenches.

To arrive at two of the villages, both Bacanou A and Bacanou B, I caught a ride on the back of a truck in another village, Bécedi. It was always a crap shoot if I made it in time or not. Getting back was even more challenging since there was so little traffic out there. The people, however, always made it worth my while because they were so gracious in offering me a place to stay, dinner and a Fanta. However, after a long day, I much more preferred to get back to Braffouéby.

Early one morning before school, I experienced fifteen minutes of terror as I attempted the commute on my new Trek bike that was gifted by the Peace Corps. Trying my best to swerve along the crater-filled dirt road, ignoring my trembling hands while balancing on the skinny tires, I became so tense and frightened that I had second thoughts, and I finally came to my senses.

“Nope, not for me!” I turned around, brought it back, and never rode the bike again.

The children, however, never gave up, begging me for a turn to ride it. Too bad they spotted it, but I knew the bike would have caused too much bickering and too many disagreements over whose turn it was. From that day on, I charged forward on foot over the rough terrain to the faraway schools since there was not really a choice, and I needed to arrive in one piece. I continued to show up out of breath and drenched in perspiration and sometimes rain often wondering if my short hair would ever dry.

The Peace Corps office in Abidjan had loads of material for students containing information for the girls’ and boys’ clubs that I decided to organize. It was a minimum of a one-and-a-half-hour bus ride away, depending on the route. Some busses would veer off the main road into the different villages to load up the tired and eager passengers who sought to earn enough money in the larger markets to feed their families. They would board the bus burdened with a variety of giant wrapped bundles ready for sale at the market, sometimes tying their load on top of the bus. A live animal strapped on the top would slow down the trip exponentially. I was routinely bewildered when I would catch one of the indirect routes since the busses operate on a loose alternating schedule, whatever that meant. One rule was in stone. If it was a direct route, the bus would never leave the station until it was full, which meant the trip entailed a lot of waiting.

Occasionally, the bus would make stops along the highway, allowing passengers to find a makeshift restroom in the nearby bushes. I vividly recall an incident where someone unintentionally tracked in a foul-smelling substance on their sandals, which served as a valuable lesson for me to never leave my backpack on the floor near the aisle. A very kind observant woman on board noticed what had happened, and then she quickly cleaned it off for me. I bought a new no-name backpack at the market that very same day which suited me just fine.

If ever there existed a hell on earth, it was Adjamé, the bus station and market in Abidjan. It was teaming with scores of poverty-stricken children peddling whatever they could get their hands on. Why weren’t they in school? It was a hustle, chaotic and gritty, and I could usually count on a tussle over someone wanting to carry my backpack for me. Everyone was desperate to sell something everywhere I looked.