Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

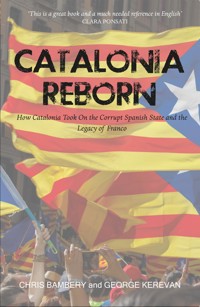

2017 saw Catalonia come under the world's spotlight as it again fought for independence and the preservation and protection of its unique Catalan culture. Answering the questions and complications behind the fight for Catalonian Independence, Catalonia Reborn is a detailed guide to the region's political, historical and cultural issues. For the layman as well as the expert, it takes the reader through the rich history of Catalonia – its language, culture and political background – to the present day, covering defining eras of the region from Franco's dictatorship to the 2017 independence referendum and elections.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 496

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CHRIS BAMBERY was born in Edinburgh. He is a writer, broadcaster, and television producer, and the Public Point of Contact for the Westminster All Party Parliamentary Group on Catalonia. He edited and contributed to Scotland: Class and Nation (1999) and is author of A Rebel’s Guide to Gramsci (2006), The Second World War: A Marxist History (2013), and A People’s History of Scotland (2014).

GEORGE KEREVAN was born in Glasgow. He is the former snp mp for East Lothian and initiated the All Party Parliamentary Group on Catalonia. He was an accredited international observer during the October 2017 Catalan referendum. He was also a senior lecturer in economics at Napier University in Edinburgh and served nine years as Associate Editor of The Scotsman, where he was chief leader writer. He is a documentary film maker and was executive producer of Fog of Srebrenica which won the Special Jury Prize at the 2015 Amsterdam International Documentary Film Festival. He is co-author of Tackling Timorous Economics (2017).

First published 2018

ISBN: 978-1-912147-38-0

The authors’ right to be identified as author of this book under the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps

produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

Printed and bound by Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow

© Chris Bambery and George Kerevan 2018

Contents

Map

Timeline

Lists of Abbreviations and Glossary

Chapter One: Birth of a Republic

Chapter Two: Catalonia, the Unknown Nation

Chapter Three: Bourgeois Catalonia, Backward Spain

Chapter Four: Civil War and Revolution

Chapter Five: Under the Iron Heel

Chapter Six: Flawed Democratic Transition

Chapter Seven: Kleptomaniac State

Chapter Eight: Dirty War in the Basque Country

Chapter Nine: Battle for a New Statute of Autonomy

Chapter Ten: Austerity and Birth of a New Separatism

Chapter Eleven: 1-0 Referendum

Chapter Twelve: The Catalan Republic Is Born

Chapter Thirteen: Into the Unknown

Notes

Map

Image: Shutterstock

Timeline

Classical Age – Fertile Catalan coastal region emerges as key link in Phoenician, Greek, Carthaginian and finally Roman Mediterranean trading empires.

8th–11th centuries – Islamic rule in most of Spain but Catalan border lands remain contested after Charles Martel defeats Arab-Berber armies at Poitiers, in 732 AD.

801 – Franks occupy Barcelona, creating a buffer between Charlemagne’s Empire and Muslim Spain. Catalan monasteries become major cultural centres transmitting knowledge between Christian and Muslim worlds.

870 – Wilfred the Hairy, Count of Gerona and Barcelona, unites four Catalan feudal counties, creating powerful state straddling the Pyrenees. Inward migration creates free peasantry and agricultural boom.

988 – Count Borrell II refuses to renew oath of loyalty to the Frankish kings. Feudal Catalonia declares de facto independence.

1023–76 – Under Ramon Berenguer I, the county of Barcelona acquires a dominant economic and political position in the area.

12th century – First mention of the term Catalonia.

1137 – Catalonia and Kingdom of Aragon to the south-west unite through marriage to become the Crown of Catalonia and Aragon, though Catalan autonomy remains intact. Over the next three centuries, Catalan empire spreads across the Western Mediterranean to Sicily and Sardinia.

1359 – The Generalitat of Catalonia established, with a president and what is considered one of Europe’s earliest parliaments.

1469 – King Ferdinand of Catalonia and Aragon marries Queen Isabella of Castile, uniting the two Spanish monarchies. But Catalonia retains self-rule, with its own political institutions, courts and laws.

1474 – First printed book in Catalan.

1640–1659 – War of the Reapers: Catalan peasants rise up against the monarchy amid anger over taxation and being forced to station and provision troops fighting against France. Strengthens tradition of popular Catalan resistance to external rule.

1659 – Spain and France sign the Treaty of the Pyrenees and Catalonia loses the northernmost part of its territory.

1705 – War of the Spanish Succession: Fearful of a French Bourbon king on the Spanish throne, the Catalans ally themselves with England in defence of their traditional autonomy.

1713 – Tory government in Great Britain resolves to end the Spanish war and signs the Treaty of Utrecht. It wins trade concessions and territory, including Gibraltar. Abandoned, Catalonia keeps fighting.

1714 – Barcelona falls to the Bourbons after a 14-month siege, on 11 September – thereafter celebrated as National Day in Catalonia. Generalitat abolished and Catalan language suppressed.

1796–1814 – French Revolutionary and Peninsula War. Napoleon at first restores Catalan independence but then annexes Catalonia to France. With end of wars, absolutism renewed under Ferdinand VII.

19th century – With the loss of its American colonies, Spain enters a century of economic decline. The exception is Catalonia, where rapid industrialisation creates a new, militant working class and triggers a cultural and linguistic renaissance, reviving Catalan nationalism.

1833 – First steam-driven textile mill in Barcelona. Burned down two years later by striking workers.

1873 – First Spanish Republic declared, committed to liberalism, modernisation and federalism. Overthrown by the army the following year. Bourbons restored.

1888 – Founding (in Barcelona) of Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) and General Workers’ Union (UGT). Universal exhibition in Barcelona.

1898 – Catalan business hurt when Spain loses Cuba. Reinforces desire of Catalan middle class for more political and economic autonomy.

1895–1906 – Zenith of Catalan Modernist architecture.

1901 – Formation of middle class Catalan Regionalist League, supporting autonomy not independence.

1909 – Working class uprising in Barcelona (‘Tragic Week’) triggered by opposition to sending Catalan conscripts to colonial war in Morocco.

1910 – Anarchist CNT founded in Barcelona.

1914 – Limited self-government returned to Catalonia under the leadership of Enric Prat de la Riba.

1917 – General strike in Barcelona.

1923 – Miguel Primo de Rivera imposes a military dictatorship in Spain. Catalan self-government and language supressed yet again.

1931 – With the collapse of the de Rivera dictatorship, Spain becomes a republic (again). An autonomous Catalan government, the Generalitat, is created under the leadership of Francesc Macia and the new Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC). Spain enters period of intense instability.

1934 – Following election of a right-wing Spanish government, new Catalan president, Luis Companys, declares independence. But this breakaway is suppressed by the army and Companys is jailed. Leftist rising in Asturias also supressed. Spain divided between left and right.

1936 – Popular Front government elected in Spain. Catalan autonomy restored under freed Companys. Franco mounts a military coup, which fails in Catalonia due to popular action. Spanish Civil War begins.

1937 – Communists and Spanish Republican government repress Catalan left-wing opposition of POUM and CNT. Andreu Nin murdered.

1939 – Barcelona occupied by Francoist forces. Catalan language banned in public, Catalan newspapers, books and culture suppressed. Thousands executed, hundreds of thousands flee into exile.

1940 – Lluis Companys executed by firing squad at Montjuic Castle.

1947 – First signs of popular resistance to Franco when Catalan used (illegally) in public at religious celebrations at Monserrat.

1951 – Tram boycott in Barcelona forces concessions from regime.

1954 – Josep Tarradellas elected Catalan President in exile.

1960s – Catalan economy revives with start of mass tourism and increasing industrialisation. Barcelona attracts large numbers of migrants from other Spanish regions. Growing cultural and political opposition to the Dictatorship led by students at Barcelona University.

1960 – Franco’s visit to Barcelona met with civil disobedience.

1962 – New strike wave leads to creation of Communist-led unions, the Commissions Obreres.

1974 – Regime executes Salvador Puig Antich, despite world-wide pleas for clemency. Mass resistance to the Dictatorship in Catalonia.

1975 – Franco dies. Juan Carlos I declared king.

1977 – First, limited democratic elections are held in Spain. One million Catalans demonstrate on 11 September. New regime allows Josep Tarradellas to return from exile.

1979 – New Statute of Autonomy for (devolved) Catalonia finally approved. Catalonia is defined as a ‘nationality’ but not a nation.

1980 - Moderate, regionalist Convergència i Unió (CIU), led by Jordi Pujol, wins the first of many elections to new Catalan parliament.

1981 – Failed military coup frightens Spanish governments into limiting autonomy for Catalonia and Basque Lands. Sets scene for later friction.

1992 – Olympics hosted in Barcelona.

2003 – Left-wing victory in Catalan elections. Massive demonstrations against Iraq War in Barcelona. Demands for greater Catalan autonomy.

2006 – New Statute of Autonomy is approved by Catalan Parliament, by the Spanish Parliament and by a referendum in Catalonia. This settlement is opposed by the Spanish right and the Popular Party.

2008 – Global banking crisis and collapse of the Spanish property bubble triggers mass unemployment in Spain and Catalonia.

2010 – Spain’s highly politicised Constitutional Court, in judgement on a case brought by the Popular Party, waters down the new Statute of Autonomy. For the first time since Franco’s death, there is a majority in Catalonia for independence.

2011 – The 15-M anti-austerity movement erupts across Spain. In Barcelona, anti-austerity and nationalist sentiments combine, undermining the traditional autonomist leadership of the CIU.

2012 – In response to the anti-austerity protests, Catalan President Artur Mas asks for negotiations on a new fiscal pact with Spain. Madrid refuses. A major independence demonstration brings 1.5 million people on to the streets of Barcelona in protest. Under pressure, Mas calls for an independence referendum. Catalan National Assembly founded.

2013 – Nearly two million people link hands across Catalonia calling for independence – possibly the largest demonstration in European history. Artur Mas asks Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy to discuss a referendum. Madrid snubs the request.

2014 – The Catalan Government holds a consultative referendum on independence. Over 80 per cent of the 2.25m votes cast favour the independence option.

2015 – Pro-independence parties win a clear majority in fresh election to the Catalan Parliament. Under pressure from the far-left CUP party, Artur Mas is replaced by Carles Puigdemont as Catalan President.

2017 –

1 October: With Madrid still refusing negotiations, the Catalan Parliament holds a second independence referendum. Despite savage Spanish police attacks on polling stations, 2,020,000 voters (91.96 per cent) answer ‘Yes’, while 177,000 say ‘No’. Puigdemont asks Madrid to enter a dialogue brokered by the EU. The Spanish Government and the EU both reject these overtures.

3 October: General strike across Catalonia in protest at Guardia Civil brutality on referendum day. Over 700,000 demonstrate in Barcelona. TV broadcast by King Filipe fails to condemn police action.

16 October: Two prominent independence leaders – Jordi Sanchez of the Catalan National Assembly and Jordi Cuixart of Omnium Cultural – arrested and imprisoned on charges of sedition.

27 October: Catalan Parliament votes to declare an independent Catalan Republic. Immediately, Spanish Senate invokes Article 155 of the constitution and imposes direct rule over Catalonia. Prime Minister Rajoy dissolves Catalan Parliament. Puigdemont and Catalan ministers escape into exile in Belgium.

7 December: Over 50,000 Catalans come to Brussels in solidarity with Puigdemont and to demand the EU intervenes in Catalonia. EU ignores.

21 December: Pro-independence parties win narrow majority in election.

2018 –

January 2018 – Three jailed Catalan independence leaders – Oriol Junqueras, Jordi Sànchez and Jordi Cuixart – file a complaint with the United Nations, saying their imprisonment in Spain breaks international law.

March 2018 – The pro-independence majority in the Catalan parliament are unable to elect Jordi Sànchez as president after the Spanish Supreme Court refused to free him from prison so he could attend the session.

A third attempt to elect a new president collapses after a proposal to install Jordi Turull was defeated by 65 votes against 64.

Spain’s Supreme Court plans to try 13 Catalan independence leaders on charges of rebellion.

April 2018 – Carles Puigdemont arrested by German police after crossing the border en route to Belgium after Spain secured a European arrest warrant while he was visiting Finland. A German court releases him on bail saying the charge of violent rebellion was inadmissible.

Seven activists from the grassroots Committees for the Defence of the Republic are arrested following their campaign of non-violent civil disobedience.

Hundreds of thousands take to the streets of Barcelona on Sunday 15 April to demand freedom for Catalan political prisoners under the slogan ‘Us Volem a Casa’ (‘We want you home’).

May 2018 – Jordi Cuixart, Jordi Sànchez, Oriol Junqueras, Joaquim Forn, Dolors Bassa, Carme Forcadell, Raul Romeva, Josep Rull and Jordi Turull remain in Spanish prisons; Carles Puigdemont is in exile in Germany awaiting trial; Clara Ponsati awaits a Scottish court decision on the validity of the European Arrest Warrant; and Meritxell Serret, Antoni Comín and Lluís Puig remain in Belgium.

List of Abbreviations and Glossary

Alianza Popular (People’s Alliance). Right-wing party founded by Manuel Fraga in 1977; precursor of Partido Popular.

ANC:Assemblea Nacional Catalana (Catalan National Assembly). Grassroots civic association organization that seeks political independence of Catalonia and Catalan-speaking areas from the Spanish state. The ANC has its origins in the Conferència Nacional per l’Estat Propi (National Conference for Our Own State), held in April 2011 in Barcelona. Formed officially in March 2012, with Carme Forcadell as President. Famous for holding mass demonstrations.

Carlism. Traditionalist, right-wing movement seeking the establishment of a separate line of the Bourbon dynasty to Spanish throne. Focal point for peasant and regionalist opposition, especially in Basque lands, defending local autonomist rights. Carlism was a significant force from 1833 until the end of the Franco regime. Today, a fringe movement.

Catalunya en Comú-Podem. Left-wing electoral coalition comprising Podem (Catalan branch of Podemos) and Catalunya en Comú, a local grouping organised by Barcelona mayor Ada Colau. Also includes Iniciativa per Catalunya-Verds (ICV), the continuation of the former Catalan communist PSUC. Confusingly, during 2015–2017, Catalunya en Comú-Podem ran under the name Catalunya Sí Que Es Pot.

CIU:Convergència i Unió (Convergence and Union). Pro-autonomy, centre-right electoral alliance comprising Democratic Convergence of Catalonia and smaller Democratic Union of Catalonia. Founded in 1978, dissolved in 2015. Under Jordi Pujol, CIU ran autonomous Catalan government for 23 years until 2003, favouring maximum devolution inside Spain rather than independence. Return to power in 2010 as part of a series of increasingly pro-independence coalitions. Dominant force in Catalan politics for most of post-Franco era.

CCOO: Comisiones Obreras (Workers’ Commissions). Trade union body originally founded in 1960s by the Spanish Communist Party and liberal Catholic workers’ groups. Illegal under Franco, the Commissions entered and subverted the state-controlled ‘vertical unions’. Today the largest trades union federation in the Spanish state.

CEDA:Confederatión Espanola de Derechas Autónomas (Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-wing Groups). Amalgam of right-wing parties formed in 1933 to oppose Spanish Republican government. In the 1933 Cortes election, CEDA won a plurality of seats, precipitating a period of intense political stability. Defeated by the Republicans and left in the 1936 Cortes election, CEDA adherents supported the subsequent military uprising. Franco ordered CEDA dissolved in 1937.

CNT: Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (National Confederation of Labour). Confederation of anarcho-syndicalist labour unions, founded in Barcelona in 1910 by an amalgamation of earlier anarchist groups. Dominant force in Catalan working class up to the Civil War.

Ciudadanos (Citizens’ Party). Spanish neo-liberal, anti-independence party launched in Catalonia in 2006 and later extended to the rest of the Spanish state.

Ciutadans (Citizens’ Party). Catalan branch of Ciudadanos.

Convergència Democràtica (Democratic Convergence). Leading Catalan autonomist party now re-named PDeCAT. The largest constituent of the old CIU coalition. Led by Jordi Pujol than Artur Mas.

CUP: Candidatura d’Unitat Popular (Popular Unity Candidacy). Far-left party in Catalonia that favours independence from Spain. Traditionally, the CUP has focused on municipal politics, and is organised around autonomous local assemblies that run in local elections.

ERC: Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (Republican Left of Catalonia). Left-wing Catalan party favouring independence for all the Catalan-speaking lands. Founded in 1931 by the union of Estat Català (Catalan State), led by Francesc Macià, and the Catalan Republican Party, led by Lluís Companys.

ETA: Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (Basque Homeland and Liberty). Radical Basque nationalist party founded in 1959, espousing independence and armed struggle.

Falange Española (Spanish Phalanx). In its final 1937 incarnation, the Falange was designated the sole legal political party during the Franco era. Created in 1934 as a merger of two earlier extremist groups, under the leadership of José Antonio Primo de Rivera. Originally, the Falange had an explicitly fascist and corporatist political ideology, though under the Franco regime it brought inside its ranks a variety of right-wing, monarchist, Carlist and Catholic-conservative elements. Officially dissolved in 1977 but many self-styled Falangist splinter groups continue to function.

GAL:Grupos Antiterroritas de Liberación (Anti-terrorist Liberation Groups). Illegal, para-military death squads created by Spanish government officials to wage secret war against ETA, 1983–1987.

Generalitat de Calalunya. Name traditionally given to the prevailing Catalan government.

Guardia Civil (Civil Guard). Spanish state para-military security force founded in 1844. Under military discipline with officers drawn from Spanish army.

Herri Batasuna (Popular Unity). Basque political coalition which supported armed struggle of ETA. Later used electoral name of Euskal Herritarrok (Basque Citizens).

ICV: Iniciativa per Catalunya Verds (Initiative for Catalonia Greens). Merger of PSUC, the former Catalan Communists, and Green Party.

IU: Izquierda Unida (United Left). Left-wing coalition formed in 1986 but dominated by PCE. Effectively now the modern incarnation of the PCE.

Junts per Catalunya (Together for Catalonia). Electoral front created by Puigdemont’s PDeCAT to fight December 2017 Catalan election. Excluded the ERC but included independent figures such as Jordi Sánchez, the President of the ANC.

Junts pel Sí (Together for Yes). Electoral front formed pro-independence parties in 2015 Catalan election, led by Artur Mas. Included Democratic Convergence and ERC.

Lliga Regionalista de Catalunya (Regionalist League of Catalonia). Usually referred to simply as the Lliga. Conservative, monarchist, right-wing Catalanist party founded in 1901 to represent interests of Catalan business and middle class. Dominant force in Catalan politics till dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. After Civil War, many prominent Lliga supporters opted to make their peace with Franco’s regime.

Òmnium Cultural. A civic association that defends and promotes the Catalan language and culture. Established in 1961 under the Franco regime when the public and institutional use of Catalan was illegal. Played a key role since 2012 in organising pro-independence demonstrations. Òmnium president, Jordi Cuixart, was remanded in custody in September 2017, charged with sedition against Spain.

Opus Dei (God’s Work). Founded by the Spanish priest Josemaria Escriva de Balaguer in 1928 and eight years later it backed Franco’s rebellion against the Spanish Republic. By the 1960s many members of Opus Dei were ministers in the Franco regime championing the need to modernise the Spanish economy, combining a technocratic outlook with Catholic fundamentalism.

PCE: Partido Comunista de España (Communist Party of Spain). Founded in 1921, after a split in PSOE. Traditionally Stalinist and pro-Moscow. Dominant opposition to Franco after Civil War but went into decline with fall of the dictatorship. From 1936, organised separately in Catalonia as PSUC. Since 1986, the PCE in the Spanish state operates as Izquierda Unida.

PDeCAT: Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català (Catalan European Democratic Party). Centre-right party founded in 2016 by Artur Mas. Direct successor to the now-defunct Democratic Convergence of Catalonia. Also known as Catalan Democratic Party. Under Artur Mas and Carles Puigdemont, PDeCAT embraced a pro-independence stance, breaking with the pro-devolution, Catalanist stance of its predecessor party.

PNV: Partido Nacionalista Vasco (Basque Nationalist Party). In Basque: Euzko Alderdi Jeltzalea (EAJ). Traditional, conservative leading party representing Basque autonomy, founded in 1895.

Podemos (‘We Can!’). Spanish centre-left, populist party founded in 2014, in the aftermath of the 15-M protests against austerity. Main leader: Pablo Iglesias. Opposed to Catalan independence.

POUM:Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista; Catalan: Partit Obrer d’Unificació Marxista (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification). A Spanish revolutionary Marxist but anti-Stalinist party, formed in 1935 by merger of the fusion of the Trotskist Izquierda Comunista de España (Communist Left of Spain) and the mainly Catalan Bloc Obrer i Camperol (Workers and Peasants’ Bloc). Led by Andreu Nin and Joaquim Maurín. Famously, the writer George Orwell served with the POUM militia.

PP: Partido Popular (People’s Party). Dominant, post-Franco right-wing party in Spain, founded in 1989.

PSC:Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya (Socialist Party of Catalonia). Catalan branch of the main Spanish Socialist Party, the PSOE, in the post-Franco era. The PSC governed Catalonia in a coalition with ERC and ICV, from 2003 to 2010.

PSOE:Partido Socialista Obrera Español (Socialist Workers’ Party). Main Spanish socialist party, founded in 1879. Formed post-Franco governments under Felipe González (1982–1996) and José Luis Zapatero (2004–2011).

PSUC: Partit Socialista Unificat de Catalunya (Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia). Formed in July 1936 through the unification of the Catalan PSOE and the Catalan Communists in the PCE. Effectively a Stalinist take-over of the local PSOE. Post-Franco, the new, social democratic PSOE created its own Catalan branch, the PSC. With the fall of the Soviet Union, the rump PSUC merged with the Greens, as the IVC.

SCC: Societat Civil Catalana. Created in April 2014, the SCC is a civic society organisation opposing Catalonia independence.

UCD: Union del Centro Democratico (Union of the Democratic Centre). Short-lived alliance of ex-Francoists and Christian Democrats, founded in 1977 under leadership of Adolfo Suárez. Won elections in 1977 and 1979 before collapsing in wake of PSOE election victory in 1982.

UGT:Unión General de Trabajadores (General Union of Workers). A major Spanish trade union, historically affiliated with the PSOE. Founded in 1888 by Pablo Iglesias Posse.

Chapter One: Birth of a Republic

To the people of Catalonia and to all the peoples of the world… Despite the violence and the repression with the intent to impede the celebration of a peaceful and democratic process, the citizens of Catalonia have voted by a majority in favour of the constitution of the Catalan Republic… The constitution of the Republic is a hand held out to dialogue…

Catalan Declaration of Independence, 27 October 2017

ON THE AFTERNOON of Friday 27 October 2017, at 3.25pm, in the salmon pink Palau del Parlament in the heart of Barcelona’s Ciutadella Park, the Second Catalan Republic was born. Even a month before, Catalonia hardly registered in global political consciousness. Now, seemingly from nowhere, a popular revolution had erupted in Western Europe for the first time since World War Two – albeit an insurgency based on peaceful mass resistance to Spanish rule. By 70 votes in favour, ten against and two unfathomable abstentions, Catalan MPS legislated a new state into being.

But the true authors of this new Republic were not the Catalan President Carles Puigdemont and his coalition of centre-right European Democrats and left-wing Republicans, trading under the banner of Junts pel Sí, or Together for Yes. Rather it was the Catalan people themselves – in their literal millions – who had marched, demonstrated, organised, protested, gone on strike and finally voted in two successive referendums to secure self-determination. Even this final vote in the Palau del Parlament had been in doubt until tens of thousands of people had taken to the streets of Barcelona chanting ‘Declare the Republic!’ and ‘We are millions, we are our institutions!’.

Such a mass intervention from below is rare enough in this elite-dominated age and deserves fully the title of revolution. Perhaps only in the final days of the old German Democratic Republic, back in 1989, have we seen an equivalent mass movement on the streets, able to impose its will on historical events. This book will tell the story of the Catalan political revolution of October 2017, of its individual participants and protagonists. But its chief dramatis personae are the tens of thousands of excited Catalans who waited expectantly in Ciutadella Park that Friday afternoon to witness the birth of their new Republic announced to the world.

Birth of the Catalan Republic, Crisis of the Spanish State

The weather was balmy, in stark contrast to the torrential rain on referendum day only four weeks earlier, when many in this same crowd had their heads split open by baton-wielding Spanish Guardia Civil bent on closing polling stations. How they cheered when the final vote was announced. Win or lose, nothing now would or could be the same for insurgent Catalonia, or for a querulous and divided Spanish state, and certainly not for a crisis-ridden, myopic European Union desperate to ignore this fresh problem on its doorstep.

The Catalan parliament building, where these events were unfolding, is soaked in history. Construction began in 1717, a bare three years after Catalonia lost its independence to Spain. Philip V – first in the long and detested Bourbon line that runs down to the present incumbent, Felipe VI – required an arsenal to dominate Barcelona. The result was the gigantic, star-shaped fortress of the Ciutadella – the largest military fortification in Europe. Swathes of Barcelona had to be demolished to make room for what became a hated symbol of Spanish occupation. By chance, during the chaotic liberal uprisings against the Bourbons in the mid-19th century, the fortress walls were destroyed. Seizing an opportunity, the wily Barcelona bourgeoisie turned the Ciutadella into an urban park and zoo. But they kept the main arsenal building, which ended up as the Municipal Art Museum. With the downfall of the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and the emergence of a democratic Spanish Republic in 1931, Catalonia declared independence. The new, autonomous Catalan parliament lacked a home. It found one instantly in that elegant Ciutadella art gallery, soon remodelled with an intimate hemicycle debating chamber.

But Catalan history was to take another turn. When Franco’s victorious fascist army occupied Barcelona in January 1939, expunging Catalan freedoms and language, the debating chamber of the Palau del Parlament was literally bricked up and left to gather cobwebs. After the dictator’s belated death in 1975, the bricks were taken down. The entombed Palau del Parlament once again became the citadel of Catalan democracy and hopes for self-determination.

Those hopes were soon dashed. For post-Franco Spain turned out to be a pseudo democracy. The transition from Francoism to parliamentary democracy involved no purge of the state apparatus nor any attempt to come to terms with the legacy of the Spanish Civil War and the repression which followed. Instead, the ruling Francoist elite created only a semblance of democratic institutions following the dictator’s death, in order to to gain access to the European Union. The result was the unique 1978 Spanish constitutional settlement: a political compromise that granted a degree of popular democratic representation and a degree of autonomy for Spain’s constituent regions and nations, while preserving as much of the old, authoritarian order as possible.

As a result, the bulk of the nation’s wealth and banking system remained in the hands of a narrow oligarchy centred on Mariano Rajoy’s Popular Party (PP), the direct political heirs of the old Falangists and Francoists. This web of corruption between bankers and politicians reached its zenith during the great financial bubble of the early 21st Century. Billions were borrowed and spent by giant Spanish construction companies to build a new generation of toll highways around Madrid. These were funded by cheap bank loans underwritten by the Spanish state (i.e. PP politicians in Madrid). At the same time, illegal cash donations flowed into the coffers of the dominant, right-wing Popular Party. With the Bank Crash of 2008, many of these vanity construction projects went bankrupt, leaving the Spanish taxpayer (including the Catalan taxpayer) to foot the bill. The declaration of the Catalan Republic was a repudiation of this corrupt system.

As we will see in later chapters, Spain is structured very differently from the more mature European capitalist economies to its north. The Franco regime had fostered state capitalism in its drive to catch up with the rest of Europe. With the end of the dictatorship, a corrupt, conservative Popular Party elite deliberately engineered the transfer of these public industries and banks into the private ownership of a clique of its friends and allies, in return for illegal funding of the party’s operations. Spanish capitalism (much like post-Soviet Russia) became dominated by a narrow circle of oligarchs, operating through private conglomerates funded by bank debt. Once Spain entered the Eurozone, and with global interest rates at rock bottom, the door was open to a gigantic property and speculation bubble. When the bubble burst in 2008, the Spanish economy imploded. Out of this economic and social crisis, the modern Catalan independence movement was born.

In May 2011, popular resistance to austerity, in particular to mass youth unemployment, touched off a spontaneous protest that occupied city squares across the Spanish state: the so-called 15-M Movement. By-passing existing political parties, the participants organised themselves via Facebook and Twitter, in the manner of the Tunisian and Egyptian activists of the Arab Spring. 15-M had major political repercussions. The crisis led to the emergence of new populist political parties: Podemos on the left and Ciudadanos (‘Citizens’) on the Blairite centre-right. It shattered the traditional Socialist Party (PSOE) leaving Spain virtually ungovernable. A series of inconclusive elections left a minority PP government clinging to power in Madrid. In Catalonia, the traditional centre-right ‘autonomist’ governing coalition – Convergència i Unió, Convergence and Union (CIU) – imploded as a result of corruption scandals and the rise of a left-wing, anti-austerity independence movement.

For decades after the fall of Franco, the Catalan secessionist movement was a political minority, motivated largely by cultural and language demands. Austerity changed that. Today 72 per cent of those supporting the Catalan Republic say they are left-wing as compared to 40 per cent who voted No. Polls also suggest that a majority of those supporting independence do so because they want to transform society and the economy. True, the language issues remain important; the Spanish Constitutional Courts continue to strike down laws that protect the Catalan mother tongue. And there is a wing of the Catalan middle class, led by Puigdemont’s Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català (European Democrats, PDeCAT), that resents Madrid for its high taxes. Since the days of Franco, Madrid has used the Catalan economy as a milch cow to fund the rest of Spain, much as London kept hold of Scotland in order to use North Sea oil earnings to fund its trade deficit. But the desire of those crowds gathering in front of the Palau del Parlament on 27 October was less about high taxes and more about social change and the Catalan Republic that could bring it about.

That inevitably meant rupture with the Spanish state. Yet even on that fateful Friday afternoon there were those in the leadership of the independence movement who were still hesitating to take that final step in breaking with Spain. In the ornate corridors of the Palau del Parlament – modelled on the Paris Opera Garnier – the pro-independence coalition led by Puigdemont, an ex-journalist and former mayor of Girona, found itself caught between two opposing forces. On the one side, there was the intransigence of the ultra-conservative Spanish government that still refused any form of dialogue with the Catalans. On the other side, there was the mass movement and the desire of an animated people to remake Catalan society. Puigdemont’s inclination was to continue to play cat and mouse with Madrid, hoping that the EU would force the Spanish state towards compromise. Even at the last minute on that decisive Friday, Puigdemont wanted to delay announcing the Republic and call fresh elections instead. But a revolt from within his own party forced his hand. Even the rank and file of the PDeCAT, which sits with the British Liberal Democrats in the European Parliament, had been pushed by the mass movement towards calling the Republic.

Few had ever expected Puigdemont to press on with the 1 October referendum in the face of Spanish legal and paramilitary threats. Ultimately, pressure from below gave him no room for manoeuvre. True, he showed unexpected skill in keeping his multi-party, multi-class, pro-independence coalition together long enough to hold 1-0 and declare the Republic. But as we shall see, Puigdemont’s short-term perspectives, and naivety in believing that the EU would eventually intervene, meant that there was no planning for what to do the day after the Republic was declared. Puigdemont’s empiricism and opportunism would have dangerous consequences. There is an old adage that those who make a revolution half way invariably dig their own graves – politically if not always literally. But on that dramatic Friday, Puigdemont had run out of ways of fending off the inevitable declaration of the Republic. Reason: Rajoy and the PP government in Madrid had initiated the legal process to impose direct rule on Catalonia, the so-called Article 155.

Rajoy triggers Article 155 and direct rule

The PP, created in 1989 as a political home for the various dissident factions of the old Francoist apparatus, remained the champion of Spain’s economic oligarchy. Under the dull technocrat Mariano Rajoy, the PP had found a new lease of life as a devout servant of Germany’s pro-austerity drive to save the Euro (and, in passing, save Germany’s profligate banking system). Germany and the EU reciprocated by turning a blind eye to anything Rajoy did internally to recentralise the Spanish state. If that meant turning a blind EU eye to Spanish corruption or the repression of self-determination in Catalonia, so be it. Bequeathed a free hand by the EU, Rajoy made use of the surge in support for Catalan independence to bolster the fading popularity of the PP by playing the unionist card. This had many advantages. As well as diverting attention from the corruption trials engulfing the party, taking a hard line against Catalan sovereignty boosted PP support in other regions of the Spanish state, united the party’s disaffected base, helped recover ground from Ciudadanos (its main competitors on the right), put Pedro Sánchez’s ‘new’ Socialist Party (PSOE) under pressure, and moved the political debate away from the economy.

Rajoy chose to make the Catalans a political scapegoat rather than confront the existential crisis of the 1978 post-Franco regime. But that had always been the default position of the PP: to revert to Spanish nationalism and centralism to paper over the cracks in the economy and society. This should have been clear to the Catalan government in Barcelona. For the PP was acting on behalf of a narrow, interlocking financial elite of private investors and landed aristocracy whose personal wealth had become inextricably bound up with the fortunes of the Spanish state. Reform of the 1978 constitutional set-up was intrinsically linked to sweeping this elite away. In essence opposing Catalan sovereignty was key to protecting the ’78 Regime.

Thus it was that in Madrid a separate drama unfolded on 27 October. In the Spanish Senate a vote was taking place to suspend the elected Catalan Parliament and impose direct rule. That morning, Rajoy made a speech outlining why he wanted direct rule. There was still time to offer some form of dialogue with Catalonia. Surely an agreed referendum taking place, as in Scotland, might defuse the crisis? But from the point of view of Rajoy and the PP, any compromise with Catalonia was impossible by definition. Lacking any sense of irony, Rajoy mocked the very idea of ‘dialogue’ in his argument for triggering 155:

The word dialogue is a lovely word. It creates good feelings. Dialogue is widely practised in Spain. Our Constitution and our laws are the product of dialogue. But dialogue has two enemies: those who abuse, ignore and forget the laws, and those who only want to listen to themselves, who do not want to understand the other party.1

Rajoy’s 45-minute speech was frequently interrupted by applause from excited PP senators. There was nothing new in his arguments: ‘In Catalonia, there has been an attempt to ignore the laws, disregard them, repeal them, violate them, any term is valid.’ He warned that Spain was faced with an ‘exceptional situation’, and claimed that ‘Article 155 is not against Catalonia but to avoid the abuse of Catalonia’. He was followed by a line of senators either heaping unionist scorn on the Catalans or else (from the PSOE and the former Communists) trying to explain why they were helping the PP bludgeon Catalan self-determination into the ground. This non-debate was stretched out deliberately as the PP manoeuvred to time the inevitable triggering of 155 for the period after the Catalan Parliament had declared the Republic.

The most dramatic moment in the 155 debate came when Jokin Bildarratz, a senator representing the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV), remarked in passing that ‘the Basque nation exists’. Instantly, incensed PP senators shouted back, ‘No it doesn’t exist!’ The Senate chamber erupted into pandemonium as the PP revealed its concept of a unitary Spain – one where there is no room for different nations and cultures to co-exist. The PP senators seemed oblivious to the fact that the Basque regional premier Iñigo Urkullu had spent the previous 72 hours trying to persuade his Catalan counterpart, Carles Puigdemont, to opt for regional elections over a unilateral declaration of independence. Urkullu’s involvement was not altruistic. PNV support in the Spanish Cortes provides the PP government with the necessary votes to pass its the budget. In exchange, the Basque administration has negotiated extra powers and extra funding from Madrid. However, the Catalan conflict has strained this cynical arrangement to the limit. The PNV finds itself propping up a Spanish unionist government which is suppressing Catalan democratic rights. It was little wonder Urkullu felt impelled to try and defuse the crisis before it spilled into Basque politics. The spectacle of boorish PP senators chanting that the Basque nation did not exist reveals the extent to which the Catalan crisis has exposed the fragile legitimacy enjoyed by the 1978 Spanish regime.

The chamber debates the Republic

Back in Barcelona, the moment had come. After Rajoy’s belligerent speech, there was now no turning back. After lunch, the debate on declaring the Republic opened in the chamber of the Palau del Parlament, with Carme Forcadell presiding in the Speaker’s Chair. Forcadell is deceptive. She may be slight and always a bit nervous, but she is the daughter of a peasant farmer – and Catalonia’s rebellious peasantry have always been the heart of the nation’s unique historic identity. Before her election to parliament in 2015, Forcadell had led the main civic independence movement, the ANC. Now she was under indictment by the Spanish Constitutional Court for having allowed independence and the 1-0 referendum to be discussed, far less voted on. She was facing 30 years in prison for her commitment to democracy.

The large delegation of Catalan mayors who were present for the debate broke into loud chants of ‘Independence! Independence!’ when the live feed from the debating chamber of the Palau del Parlament finally appeared on the television screens. The debate was both emotional and angry, as might be expected. In the Catalan chamber, members do not speak from their seats but come to a lectern that faces the hemisphere, like an actor addressing the audience. The chamber is quite intimate. The parties supporting independence sat to the left of the person addressing them, while the Unionist parties were to the right. The speeches were short. There was little flowery language.

The most vitriolic and choleric voice in the debate was that of Carlos Carrizosa, of the Ciudadanos. The voice of the Spanish professional middle class and liberal parts of big business, Ciudadanos lacked the political guts to try and reform the creaking 1978 Spanish constitution that keeps the corrupt PP in power. Instead, it took out its frustrations on the Catalan independence movement, the one force willing to take on the PP and the economic oligarchy it protects. A frenzied Carrizosa railed at the ranks of pro-independence deputies, calling them totalitarians:

You have driven us to social confrontation, you have divided Catalan society, you have ruined it, and that is why you are going to pass into history, Mr Puigdemont.2

But for Carles Riera (of the far left CUP) a declaration of independence was ‘the best path for social transformation’ and ‘the construction of a free, feminist and socialist society’. He summed up: ‘We will be a refuge, for all of those who want a better world.’3

Finally, it was time to vote. The opposition deputies from the PP, Ciudadanos and the Catalan Socialist Party (the local PSOE) ostentatiously quit the chamber in protest. As a gesture, the PP unionists left behind Spanish flags draped on their seats. Parliamentary lawyers then issued a formal warning that a vote on independence could be declared illegal by the Constitutional Court. To protect pro-independence deputies from being charged with rebellion, it was decided to hold a secret ballot. The ballot box was placed on Speaker Carme Forcadell’s table in preparation for the vote.

Forcadell then read out the preamble to the independence motion. This ‘declarative’ preamble was not part of the motion itself but a political justification of what was about to happen. The text is addressed to ‘the people of Catalonia and to all the peoples of the world’. It begins by stressing the historical continuity of the nation and its democratic heritage:

The Catalan nation, its language and its culture have one thousand years of history. For centuries, Catalonia has endowed and enjoyed its own institutions which have exercised self-government in full… Parliamentarianism has been, during periods of liberty, the pillar upon which these institutions have sustained themselves…4

The document then stresses the attempts, post-Franco, to reach a political accommodation for legitimate Catalan aspirations within the Spanish state. Unfortunately, it concludes, ‘the Spanish state has responded to that loyalty with the denial of the recognition of Catalonia as a nation’ and since the 2008 economic crisis with a ‘recentralisation’ that has led to ‘a profoundly unjust economic treatment, and linguistic and cultural discrimination’. In other words, Catalonia is more oppressed than ever. The 2006 revision to the internal Statute of Autonomy ‘would have been the new stable and lasting marker of a bilateral relationship between Catalonia and Spain’, but this was vetoed.

The last straw was the ‘brutal police operation of a military nature and style orchestrated by the Spanish state’ against voters during the 1 October referendum. However, despite the violence and the repression, ‘the citizens of Catalonia have voted by a majority in favour of the constitution of the Catalan Republic’ thus providing a mandate for independence. The historic document concludes by pointing to the tasks of the new state: ‘The Catalan Republic is an opportunity to correct the current democratic and social deficits, and to build a more prosperous, more just, more secure, more sustainable society with greater solidarity.’

In the Catalan fashion, deputies were called by the speaker one by one to vote. Despite the secret poll, many held up their ballot paper to the cameras. At 3.25pm Catalan independence was passed, by 70 votes in favour to 10 against, plus two recorded abstentions. Another 53 deputies representing the main unionist parties abstained by virtue of not being in the chamber for the vote. In the words of the declaration, Catalonia was now ‘an independent, sovereign, legal, democratic, socially-conscious state’. The leaders of the independence movement – Puigdemont, Forcadell, and Oriol Junqueras of the ERC – shook hands. They were overseen by the ghosts of all those who had gone before them in the Palau del Parlament, not least Lluís Companys, the murdered president of the first Catalan Republic.

Response to independence – Back to the streets

The response to the historic declaration of Catalan independence was not long in coming. While the crowds outside the Palau del Parlament broke into cheers and song, the Spanish Senate immediately ratified Rajoy’s application for Article 155. There were 214 votes for, 47 against, and just one abstention. Big business was also quick to declare its view. Spain’s main business association, the CEOE, issued a statement rejecting the ‘illegal’ decision of the Catalan parliament. Others tried to steer a middle course between Spanish unionism and repression on the one hand, and the unilateral declaration of independence on the other. In a long Facebook post, Barcelona Mayor Ada Colau showed her opposition to both the independence declaration in the Catalan parliament and Article 155 in the Senate: ‘Not in my name. No to 155 and UDI'.

Abroad, prompted by a massive diplomatic effort engineered by the Rajoy government, country after country issued statements reaffirming support for the ‘unity’ of the Spanish state, a mantra that sounded more like a religious confession than any serious attempt to grapple with the European and global consequences of the crisis. Donald Tusk, the EU Council President, immediately tweeted to the world; ‘For the EU nothing changes. Spain remains our only interlocutor. I hope the Spanish government favours force of argument, not argument of force’. The latter plea, which went largely unnoticed, suggested the EU was petrified that Spanish repression might get out of hand, now Article 155 had been triggered. But that did not stop Tusk giving diplomatic cover to Madrid’s bid to close down a democratically elected Catalan parliament.

Only in Scotland was there anything like a positive response to the Catalan UDI. Hard on the vote in the Palau del Parlament, the External Affairs secretary of the Scottish Government, Fiona Hyslop, issued a carefully worded statement which began:

We understand and respect the position of the Catalan Government. While Spain has the right to oppose independence, the people of Catalonia must have the ability to determine their own future. Today’s Declaration of Independence came about only after repeated calls for dialogue were refused.5

Hyslop went on to demand both Madrid and the European Union engage in negotiations with Catalonia.

Meanwhile, in the chamber, President Puigdemont addressed several hundred supporters. He said: ‘In the days ahead we must keep to our values of pacificism and dignity. It’s in our, in your, hands to build the Republic.’ Those gathered then erupted into the Catalan anthem ‘Els Segadors’ (The Reapers) and chants of ‘Liberty!’

But now there was to be a strange absence. The crowds waiting expectantly outside the Palau del Parlament expected Puigdemont and the other leaders of the movement to appear before them. This was the ‘balcony’ moment when the people and their leaders would celebrate the public declaration of their new Republic. But the crowds who had created a revolution were destined to wait in vain. There would be no ‘balcony’ moment, no speeches to the Catalan people as there had been at the time of the declaration of the First Catalan Republic in 1931. Puigdemont, having led them to the declaration of the new state, simply disappeared from public view, leaving Catalans bemused and confused. This was an omen of things to come.

For the unilateral declaration of independence that Friday afternoon was not the launch of a new state with a functioning government. Within hours Madrid had taken control of the Catalan administration without any palpable resistance. Within days, Puigdemont had fled to Belgium. He issued no orders to the mass movement, leaving people demoralised and unsure what to do next. Meanwhile, Rajoy filled the political vacuum by calling fresh Catalan elections scheduled for 23 December. After the heady days of 27 November, Catalonia faced a great anti-climax. What had gone wrong?

Here we arrive at the final theme of this book. Momentous as was Friday 27 October 2017 in the long and turbulent history of Catalonia, we should not romanticise a single day’s events. For the Catalan revolution is a process in which 27 October was but one weigh station. Driven from below by a mass movement unprecedented in 21st century Europe, the Catalan independence movement is transcending being a mere political challenge to the Spanish 1978 regime. By overflowing these democratic boundaries, the Catalan struggle for self-determination. This is its significance for the rest of Europe and the world.

The modern Catalan independence movement – in distinction to contemporary populist and racist movements in Eastern Europe – is progressive in nature. At root, the upsurge in Catalonia is best understood as a rebellion against the authoritarian nationalism of the Spanish state. It is driven by a popular desire to reform and democratise the authoritarian and (despite its ‘devolved’ aspects) centralist Spanish regime, to defend Catalan language and culture, and to oppose the austerity policies imposed by Madrid. As we will see in later chapters, Catalan independence is not – and never was – a project of the Catalan bourgoisie. The latter have always, in the final resort, preferred staying with authoritarian Spain, the better to protect their material interests. Today, the left social democratic Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya, or Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), has become the most popular pro-independence party. The anti-capitalist Candidatura d’Unitat Popular, or Popular Unity (CUP), won ten seats in 2015 Catalan elections as well as capturing a raft of mayoralties. CUP’s parliamentary bargaining power enabled it not only to make the Junts pel Sí coalition hold the 1-0 referendum, but also to force the Catalan government to ban evictions and close migrant detention centres.

As a result, the Catalan political crisis cannot be resolved within the boundaries of the present, repressive Spanish state. Equally, it will not be resolved without the independence movement making a thorough balance sheet of the October referendum. The vacuum that emerged at the very moment the Republic was declared on 27 October exposed the political limitations of Puigdemont and the PDeCAT wing of the independence struggle. Yet within days the mass movement began to revive despite the failure of the parliamentary leadership. The Committees for the Defence of the Referendum, which had emerged spontaneously in response to the Guardia Civil raids and attacks on polling stations, soon took up the challenge of organising public protests over the jailing of government ministers. The Republic of 27 October was indeed alive and kicking – not in the gilded splendour of the Palau del Parlament, but in streets and squares across Catalonia.

The birth pangs of that Peoples’ Republic, the parallel crisis of the neo-Francoist 1978 Spanish regime, and the pivotal role played by the mass movement of ordinary Catalans struggling for democratic and social change constitute the theme of this book. Where the story finally ends will be determined on the streets.

Chapter Two: Catalonia, the Unknown Nation

‘What is Catalan?’

‘Why, the language of Catalonia – of the islands, of the whole of the Mediterranean coast down to Alicante and beyond. Of Barcelona. Of Lerida. All the richest part of the peninsula.’

‘You astonish me. I had no notion of it. Another language, sir? But I dare say it is much the same thing – a putain, as they say in French.’

‘Oh no, nothing of the kind – not like at all. A far finer language. More learned, more literary. Much nearer the Latin. And by the by, I believe the word is patois, sir, if you will allow me.’

Aubrey and Marurin dialogue, from Master and Commander by Patrick O’Brian

BARCELONA IS ONE of the truly great cities of the world. Every year some eight million visitors flock to it for its architecture, its culture and its food. Others travel to the beach resorts of the Costa Brava and the Costa Dorada, to the north and south of the city. The more intrepid might go mountaineering or hillwalking in the Pyrenees to the north or skiing in winter. Yet many are unaware (at least until the current independence struggle made the global headlines) that they are in one of the oldest nations in Europe – Catalonia. The language and culture of Catalonia are as distinct from Spain as are Scotland’s from England or Quebec's from English-speaking Canada.

Non-Catalans are equally unaware of just how many contemporary Catalans they might know and how passionate they are about their native land. There is Pep Guardiola, the FC Barça hero who is a staunch advocate of Catalan independence, even standing as a candidate for the pro-independence coalition Junts pel Sí. The Catalan tenor José Carreras is adamant: ‘I am pro-independence and I am very patriotic. Sometimes you have to express how you feel, even if it could cause you problems in some situations.’ Gerard Piqué, Barcelona defender and husband of Colombian pop star Shakira, is also in favour of Catalan self-determination, making it a point to march in the annual Diada, Catalonia’s National Day.

Catalonia’s recent cultural contribution to the world has been astonishing. The opera singer Montserrat Caballé was born in Barcelona in 1933. Pau Casals, arguably one of the best world’s greatest-ever cellists, had to go into exile from his native Catalonia during the Civil War. The surrealist painter Salvador Dali was a native and devotee of Figueres. Picasso, though born in Malagá, moved to Barcelona when he was seven and adopted it as his home. He learned Catalan and his early paintings are redolent with motifs of rural Catalan life. His friend and fellow artist, Joan Miró described himself as an ‘internationalist Catalan’. A Miró tapestry at the World Trade Centre was the most important work of art lost during the 11 September attacks in New York. More prosaically, Bacardi rum was founded by a Catalan: Facund Bacardí i Massó from Sitges.

Catalonia is a proud but welcoming nation. Since 1978, following the end of the dictatorship of General Francesco Franco, who ruled all Spain with an iron fist from his victory in the Spanish Civil War in 1939 until his death in 1975, Catalonia has enjoyed self-government in many matters. But the Spanish Government in Madrid has kept crucial powers – economic, military and diplomatic – under its own control. Indeed, in recent years it has tried to take many powers back. In the last decade, the demand for independence has grown in Catalonia – from only a small minority favouring a break away at the start of this century to something approaching a majority now. To understand Catalonia’s position within the Spanish state, past and present, its democratic deficit and the bitter scars left by a fascist dictatorship, it is necessary to look back.

Firstly, the language is important. The Irish writer Colm Tóibín has lived in Barcelona and says this of his sometime home:

On the positive side is that it’s not hard to become Catalan. And if you look at the last 150 years, Catalans seem in general to import every generation. For example, a lot of factory workers, whose children become Catalans. It’s not a matter of blood. It’s not a matter of religion. It is merely a matter of speaking the language and living here with a view to permanence. But I suppose what people really do mind is the business of, if there are three people in the room and one speaks only Spanish and the other two speak Catalan and Spanish, the Catalans will talk Spanish to the Spaniard but every time they turn towards each other, they’ll move back into Catalan. That drives Spaniards nuts. It’s one of the things that... ‘why can’t they’. It’s always ‘why can’t they...’6

But Catalans could not always speak their language in public or study it at school or university. Antoni Mas grew up under the Franco regime and recalled that his family spoke Catalan only at home because the police would act if they heard it being spoken in public. ‘We couldn’t speak Catalan in school… they would beat you,’ Antoni recalled. Despite that he was not intimidated, and, in 1972, aged 20, together with two friends he began publishing an underground Catalan magazine, aided by sympathetic local priests. ‘I was very young and without fear of anything,’ he says of those years, the dying years of the regime but a time when its use of repression remained vicious.

Fresh in Antoni’s memory is the suggestion of José Ignacio Wert, the Education Minister in the Spanish Government from 2011 until June 2016, that Catalan children needed to be ‘re-Spanishised’. Antoni’s memory of repression under Franco was brought alive in 2015 when Pedro Morenés, the Spanish defence minister, stated that the army would not intervene in Catalonia, but only as long as ‘everybody does their duty’.7

After Franco died there was a concerted attempt by the Spanish ruling elite and the main political parties to argue that people should put the Civil War behind them. To smooth the transition to democracy, Spain passed an amnesty law pardoning political crimes committed in the past – the so-called Pacto del Olvido (Pact of Forgetting). The bitter legacy of the dictatorship was scarcely spoken about. But a new generation, at the beginning of the 21st century, began to demand answers as to what happened to those who were on the losing side, particularly regarding the fate of grandparents, great-grandparents and relatives who were among the missing. Those taken away by Franco’s forces and executed, and whose bodies were dumped in mass graves. The Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARMH), has documented 114,226 cases of men and women buried in mass graves around Spain. ‘There are at least 3,000 mass graves. We’re not even sure exactly how many, but it’s a lot,’ said Emilio Silva, head of the AMRH.8

The scale of those buried in mass graves is staggering: ‘Historical memory activists say that the remains of more than 100,000 Spanish victims of Franco from during and after the civil war still lie in unmarked graves, an estimate supported by many historians. Amnesty International says that Spain has the second-highest number of such graves in the world, after Cambodia.’9

Yet the current ruling People’s Party, while not itself Francoist, has its roots in that regime and has systematically blocked attempts to uncover the graves. Other examples leave a bad taste in the mouths of Catalans, and many Spaniards: it recently emerged that the PP government of José María Aznar gave the Francisco Franco Foundation €150,000 between 2000 and 2003.

The Catalan government has gone far further than its counterpart in Madrid in trying to trace the missing and commemorate those who fought to defend the legitimate governments of both Spain and Catalonia which Franco wanted removed. That reflects the fact that most Catalans opposed the Generalissimo. Yet when democracy came to Spain there was no purge of Franco supporters by the state apparatus. The judges, army officers, senior civil servants and police chiefs kept their jobs. Their children and grandchildren often took the same jobs. Catalans recall that the head of Franco’s secret police in Barcelona, a man renowned for torturing political prisoners, kept his job after his chief died.

The corruption that existed in the Francoist regime was inherited by the new democratic Spain, where it is endemic. This is resented by the Catalans, who fear that it will infect their political order. It has already infected the royal family. King Juan Carlos was Franco’s designated heir, but he was forced to abdicate following a corruption scandal involving his daughter and son-in-law. Since then more dirty washing has been exposed involving the royals.