11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pitkin

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

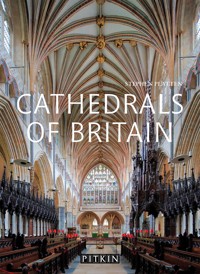

For centuries the great religious buildings of Great Britain have inspired and fascinated pilgrims and visitors from around the world. The beauty and diversity of British ecclesiastical architecture is superbly captured in this guide to over 60 of Britain's finest cathedrals. This definitive guide contains over 130 magnificent colour photographs that capture the enduring appeal of these great monuments to the Christian tradition. Extended entries are included on Durham Cathedral, York Minster, Lincoln Cathedral, Norwich Cathedral, Gloucester Cathedral, Ely Cathedral, Winchester Cathedral, Salisbury Cathedral, Exeter Cathedral, St Paul's Cathedral, Canterbury Cathedral, Glasgow Cathedral, St David's Cathedral. This definitive guide contains over 130 magnificent colour photographs that capture the enduring appeal of these great monuments to the Christian tradition. Extended entries are included on Durham Cathedral, York Minster, Lincoln Cathedral, Norwich Cathedral, Gloucester Cathedral, Ely Cathedral, Winchester Cathedral, Salisbury Cathedral, Exeter Cathedral, St Pauls Cathedral, Canterbury Cathedral, Glasgow Cathedral, St Davids Cathedral.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 158

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

THE NORTH

Introduction

Carlisle Cathedral

Newcastle Cathedral

Bradford Cathedral

Durham Cathedral

Ripon Cathedral

York Minster

St Anne’s Cathedral, Leeds

Blackburn Cathedral

Wakefield Cathedral

Manchester Cathedral

Liverpool Cathedral

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral

Sheffield Cathedral

THE MIDLANDS

Introduction

Chester Cathedral

Derby Cathedral

Southwell Minster

Lincoln Cathedral

Lichfield Cathedral

Leicester Cathedral

Birmingham Cathedral

Coventry Cathedral

EAST ANGLIA

Introduction

Norwich Cathedral

Roman Catholic Cathedral of St John the Baptist, Norwich

Brentwood Cathedral

Peterborough Cathedral

Ely Cathedral

St Edmundsbury Cathedral

Chelmsford Cathedral

HEART OF ENGLAND

Introduction

Worcester Cathedral

Hereford Cathedral

Gloucester Cathedral

Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

LONDON AND THE SOUTH-EAST

Introduction

St Albans Cathedral

Arundel Cathedral

St Paul’s Cathedral

Westminster Cathedral

Southwark Cathedral

Rochester Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral

Guildford Cathedral

Chichester Cathedral

Portsmouth Cathedral

Winchester Cathedral

THE SOUTH-WEST

Introduction

Bristol Cathedral

Salisbury Cathedral

Wells Cathedral

Exeter Cathedral

Truro Cathedral

Clifton Cathedral

SCOTLAND

Introduction

Cathedral of St Magnus, Kirkwall

St Machar’s Cathedral, Aberdeen

St Columba’s Cathedral, Oban

St Ninian’s Cathedral, Perth

Dunblane Cathedral

St Giles’ High Kirk, Edinburgh

St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh

Glasgow Cathedral

Cathedral of The Isles

WALES

Introduction

St Asaph Cathedral

Bangor Cathedral

Newport Cathedral

Brecon Cathedral

St Davids Cathedral

Llandaff Cathedral

Glossary

Index

INTRODUCTION

Journeying across Europe, how might one begin to define a medieval city? It’s as likely as not that one might begin with the cathedral and the ‘cathedral quarter’ which often nestles around the great church. Cathedrals invariably sit at the heart of historic cities and, in England, it is often assumed that the status of a city is assured by the presence of its cathedral. Strictly speaking that is not the case. In Lancashire, for example, Blackburn, with its cathedral remains a ‘town’, whereas nearby Preston, with no cathedral, has been granted a charter as a ‘city’.

Nonetheless, cathedral and city frequently evolve together and even the smallest cathedral locations often sport the name city locally, as for example with Southwell. So, across Europe, cities will be remembered by the distinctiveness of their cathedrals. Salamanca in Spain is unique with its old and new cathedrals adjoining each other like Siamese twins. The compact central German city of Bamberg has at its heart an unusual cathedral with stepped apses at either end. Florence is identified by the dome of its Duomo and Milan by the myriad pinnacles of its cathedral church. Chartres is perhaps best of all known for its treasury of stained glass.

Salisbury Cathedral’s vast lawns.

England too brings its own character. Few English cathedrals have the closely packed precinct which is so common in France; Truro is possibly the most notable exception with the church tucked into its centre. But more characteristic of the English pattern is the ‘close’, often an extended and sometimes walled precinct with more open space. Salisbury is surrounded by vast billiard-table-like lawns. Norwich’s close is a village within the city’s heart; Norwich shares with Wells its own water gate. Lichfield and Peterborough are each set within a compact, almost islanded close. Gloucester’s close protected the cathedral from the growing nineteenth-century industrial incursions. Lincoln stands astride its broad ‘Minster Yard’, proudly majestic on its prominent cliff. Durham has retained so much of its former monastic infrastructure and Canterbury’s precincts include splendid ruins alongside the great monastic cathedral building itself. So essentially ‘English’ are these locations assumed to be that even a brand of cheese has gained its reputation by being described as ‘Cathedral City’.

But even within Britain, cathedrals are not unique to England. The six Welsh Anglican cathedrals all have medieval, and indeed earlier, roots. St Davids and Llandaff are again placed within the wider expanses of a precinct. Bangor, St Asaph’s and Newport are more focal within their towns or cities. Brecon carries something of each of these. In Scotland, the complexities of the Reformation have left a more ‘mixed economy’, and nowhere are there the exact equivalent of English cathedral closes. But the magnificence and glory of the buildings remains in common, from St Mungo’s in Glasgow in the south to the cathedral of St Magnus in Kirkwall, far north in Orkney. More modest, but architecturally attractive are St Ninian’s, Perth and the Cathedral of the Isles. St Giles’ High Kirk, Edinburgh and St Machar’s, Aberdeen retain the craggy majesty of Scottish ecclesiastical architecture.

THE BISHOP’S CHURCH

Cathedrals take their name, of course, from the ‘cathedra’ or bishop’s throne, which stands at their heart. A cathedral is thus the church of the bishop, the focus of his teaching authority. Early on, cathedrals would have been basilical in form, that is oblong with an apsidal (semi-circular) end. At the centre of this semi-circle sat the bishop, flanked by his college of advisers, teaching his assembled flock. In Norwich, the eastern cathedra preserves this pattern, at the heart of a ‘basilican’ presbytery. Over the centuries the pattern of cathedral building evolved and many of them became cruciform (cross-shaped) in plan. Often this came about through association with a monastery. In England particularly, many of the cathedrals in the Middle Ages were administered by Benedictine monks: Worcester, Canterbury, Peterborough, Durham, Ely, Gloucester, Winchester, Carlisle and Norwich are examples. In these cathedrals it was the ‘prior’ who ran the monastery; the bishop, who lived in separate accommodation, was de facto the monastery’s abbot. Other English cathedrals were secular from the beginning with a college of canons at their heart. Such was the case in York, Lincoln, Hereford, Chichester, Salisbury and St Paul’s in London.

ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT

The style of architecture of English cathedrals and abbeys developed just as did the communities who inhabited them. The simplicity of Saxon architecture, often with fairly primitive round-headed arches and windows, gave way to the austere strength of the Romanesque style. Romanesque took its name from the solid round arcades and strong pillars which had developed from Roman architecture. In England this style is primarily associated with the Norman invaders and is often simply styled Norman. Durham Cathedral and Tewkesbury Abbey are two good examples from this period. St Albans, a cathedral only since the late nineteenth century, displays the earliest Romanesque, almost halfway between the earlier Saxon style used in the original abbey on that site.

In the late-Romanesque period the arches began to become pointed and this style is often termed Transitional. In the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, Romanesque gave way to the lighter touch of Early English, focused on the familiar three slender and parallel lancets seen at Rievaulx, at Whitby, and in the soaring elegance of Salisbury Cathedral. Early English marks the beginnings of medieval English Gothic, which matured into the intricacy of the Decorated and Geometric tracery familiar in so many English parish churches. Among cathedrals, York Minster is a splendid example, as is the nave of Beverley Minster. The apotheosis of English Gothic is reached in the Perpendicular period, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, with its strong vertical lines and sumptuous fan-vaulting. Early fourteenth century displays of this style of vaulting can be seen in the cloisters at Gloucester and Wells. St George’s Chapel, Windsor, and King’s College Chapel, Cambridge, are perfect examples. The nave of Canterbury Cathedral is another magnificent expression of the Perpendicular style.

Lady Chapel, Ely Cathedral.

Canterbury Cathedral’s Perpendicular nave.

The Renaissance led eventually to the rediscovery of the principles of Classical architecture, and the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw a flowering of the Classical style. The small city centre cathedrals in Derby and Birmingham are built elegantly in this manner and Wren’s rebuilding of St Paul’s in London is the most triumphant example of this style. In the nineteenth century, medieval Gothic was revived: Truro Cathedral, the Anglican cathedral in Liverpool and even the smaller Roman Catholic cathedral in Oban are each effectively born of this rediscovery of medievalism, albeit in a most creative manner. In some ways, even Guildford and Coventry owe something of their origins to a modernised or transformed Gothic. Modernism has led to a far greater freedom of expression, and different routes have been followed. The Roman Catholic cathedrals at Brentwood, at Clifton in Bristol, and at Liverpool testify to this variety, and it is to this myriad mixture of architectural styles and expression that this book seeks to introduce you. Among the Welsh medieval cathedrals are many similarities; in Scotland there is a greater independence of style, although both St Mungo’s, Glasgow, and St Giles’, Edinburgh, were influenced by the Gothic of northern England.

St Paul’s Cathedral, London.

THE NORTH

The wisdom of Aidan and the contemplative holiness of Cuthbert still linger in the marches of the ancient kingdom of Northumbria. The Celtic mission is imprinted upon the landscape and although Lindisfarne, Whitby, Hexham and Ripon now boast buildings or ruins from a later age, the network of monasteries goes back to early times. The Normans took over many sites of the early Celtic church, which had finally found confluence with the Roman tradition at the Synod of Whitby. This history is reflected in the surviving crypt at Ripon, part of St Wilfrid’s early minster church. Not far from Wakefield is Dewsbury Minster where St Paulinus was baptised.

Carlisle offers a mixture of styles, and then in York Minster we see the apotheosis of English Gothic. It has the greatest wealth of medieval glass in England and the Five Sisters window with its grisaille colouring is surely one of the wonders of the world. All this is built upon the mixed Roman and Celtic traditions of Wilfrid and Paulinus. The Norman period which links this with the later Gothic is still visible within the minster’s crypt, alongside the tomb of St William of York. Newcastle, Bradford and Sheffield all include English Gothic of varying periods. Even Blackburn has a Gothic Revival motif in its main structure. Liverpool’s Anglican cathedral offers the final expression of Gothic Revival.

Chester Cathedral.

CARLISLE CATHEDRAL

Carlisle Cathedral has seen perhaps greater ravages from a tempestuous past than most cathedrals; the truncated nave is the most obvious evidence of this. More cryptic evidence of its place on the frontier between England and Scotland is in its stones used originally either in Hadrian’s Wall, or in the wall of the Roman city. All this adds to the cathedral’s uniqueness, which is enhanced by it being the only medieval monastic cathedral to have been set within an Augustinian rather than a Benedictine priory.

Viewing the cathedral before entering it, it is easy to appreciate something of its history. King Henry I founded the Augustinian priory and church of St Mary in 1123. In 1133 he carved a new diocese of Carlisle out of the See of Durham and within ten years of its foundation the priory church became a cathedral. From the beginning it was cruciform in plan. The remains of the nave are part of the earliest Romanesque building, constructed by Bishop Athelwold, the first bishop. The central tower was rebuilt by Bishop Strickland between 1400 and 1419.

The nave, converted into the chapel of the Border Regiment by the architect Stephen Dykes Bower in 1949, contains fine Romanesque arcading. The missing four and a half bays were demolished during the Puritan Revolution between 1649 and 1652. The transepts are also Romanesque; the north transept forms St Wilfrid’s chapel and includes the Brougham triptych, carved in Antwerp around 1510. Moving into the choir, the architecture becomes Gothic. After a fire in 1292 destroyed much of the arcading, the remaining work was retained and supported by new piers. The splendid Decorated great east window parallels similar work at York Minster and Selby Abbey. The fifteenth-century stalls in the choir are very fine; on the backs of the stalls in the south aisle paintings tell the story of St Augustine, and in the north aisle, that of St Anthony and St Cuthbert.

Good evidence of the former monastery remains, in the Prior’s Tower, Gatehouse, Tithe Barn and in the noble refectory (fratry) which became the Chapter House in the seventeenth century. In October 2018, the Fratry Project began. A cloister-style building at the south-west corner of the cathedral will make the ancient fratry more accessible and provide new hospitality facilities.

Viewed from the south west.

NEWCASTLE CATHEDRAL

Of Newcastle’s medieval past, the two most prominent surviving features are without doubt, the castle keep and the nearby striking crown spire of St Nicholas’ church, which, since the creation of the diocese in 1882, has been the cathedral. The crown spire was the inspiration later on for that of St Giles’ High Kirk in Edinburgh.

The massive crossing piers owe their origin to the rebuilding of the church in the fourteenth century when nave and choir were constructed. In the north and south transepts, the south aisle and clerestory windows are part of the original Decorated period.

The ingenious design of the crown spire dates to 1435–70. Blackett’s library of 1736 is notable. The fine organ case is by the celebrated London organ builder, Renatus Harris. The superb Perpendicular font and cover (depicting the Coronation of the Virgin) are from c. 1500.

Amongst other treasures is Tintoretto’s painting of Christ washing the disciples’ feet. The delightful Maddison memorial in the south transept depicting Henry and Elizabeth Maddison and their 16 children is the pièce de résistance. Stephen Cox’s Eucharistic sculpture is on the rear of the reredos wall. The planned removal of the pews will create a greater sense of space and light; alongside the internal work, the western churchyard will be landscaped making the cathedral more obviously welcoming to all.

The medieval crown spire.

BRADFORD CATHEDRAL

Just to the north of Bradford stands the ancient parish church of St Peter. With the foundation of the Diocese of Bradford in 1919, St Peter’s became the cathedral. The nave, which is the oldest part of the building, was completed in 1458 and the oak roof resting on splendid painted angels was added in 1724. The gritstone tower in Perpendicular style was finished by 1508.

The font stands at the crossing of the entrance aisles at the west end of the cathedral; its cover is a spectacular piece of Perpendicular with a crocketed spire, sitting on a series of buttresses with fine tracery. Edward Maufe (also the architect of Guildford Cathedral) was commissioned to extend the cathedral between 1952 and 1965. These additions are in simplified Gothic.

The cathedral is blessed with some fine wall tablets including those to the Lister family. Joseph Priestley, the notable scientist from nearby is commemorated.

There is some very fine stained glass in the cathedral: some early work by Morris and Co, in the easternmost part of the building, more Morris windows in the west wall and some good Shrigley and Hunt glass in the north wall. A recent claim to fame by Bradford is that it was the first cathedral to use solar panels to generate electrical power. In the south transept there are some fine examples of the stained glass work of Charles Eamer Kempe (1837–1907).

Viewed from the north east.

DURHAM CATHEDRAL

The view of Durham when approaching by train is unforgettable. A meander in the River Wear causes a stark outcrop of rock almost to form an island. This island is crowned both by the Norman castle and also by the magnificent strength and nobility of the cathedral. The origins of this great church (a World Heritage Site) lie further back still, in the gentleness of St Cuthbert’s mission to the villages and farmsteads within the forests and wild moors of Northumbria. When Cuthbert died in 687 he was buried first on the ‘Holy Island’ of Lindisfarne. Three hundred years later, following waves of Danish invasions which necessitated the peripatetic movement of the saint’s relics throughout Northumbria and the Scottish borders, Cuthbert’s remains were reburied in this safe place where Durham Cathedral now stands. Thus began the monastic life of Durham, which was later founded as a Benedictine community. Cuthbert’s shrine remains the most sacred place in this stunning building.

Viewed from the River Wear.

Building began in 1093, when Durham was given palatine status by William the Conqueror, during the episcopate of William of St Carilef; the cathedral – built for a prince-bishop who held temporal powers delegated by the monarch – contains undoubtedly the most consistent Romanesque architecture on this scale of any church in England. The main structure of the building took only 42 years to construct, though building continued throughout the twelfth century when the chapter house and Galilee Chapel were added. This western aisled chapel is the second most holy place in this remarkable building, for here is buried the Venerable Bede, who was the first to chronicle the history of the English people in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Bede drew together the complex threads which combined to form the story of the Roman and the Celtic missions to England; the cathedral’s own history is rooted in this rich confluence of tradition.

The cathedral is approached from Palace Green, and entered through the north door, with its splendid twelfth-century Sanctuary Knocker (now a facsimile – the original is in the cathedral museum). The sheer strength and proportion of the building becomes immediately apparent when standing in the nave.

The alternating composite and circular columns with their twisting ‘barley sugar’ decoration lead the eye up into the choir, and then beyond through the Neville Screen (1380) to the shrine of St Cuthbert, and eventually to the Chapel of the Nine Altars, which forms the easternmost part of the cathedral.

The nave, transepts and choir speak in essence of a consistent use of Romanesque architectural language. The forms are sophisticated, with deeply recessed clerestory windows, bold decoration of the columns, and the earliest rib-vaulting in Europe. The four crossing arches each reach upward to 20 metres (68 feet) in height. The cloister and monastic buildings (including the vast Deanery) also owe their earliest form to the talent of Norman masons.

The story of the cathedral, however, does not end with the Norman builders. Bishop Richard le Poore, in the period 1233–44, replaced a decaying Romanesque apse with a fine Gothic conclusion to the cathedral in the Chapel of the Nine Altars. Bishop Hatfield’s tomb of 1333 forms the base of the loftiest episcopal throne in Christendom, later embellished with a seventeenth-century staircase and gallery. St Cuthbert’s medieval shrine was lost at the Reformation; now a stone slab is crowned with a colourful tester by Sir Ninian Comper. The medieval screen between choir and nave was sadly removed in the mid-nineteenth century during a period of enthusiasm for openness. It was, however, replaced in 1876 by Sir George Gilbert Scott’s marble screen, which acts as a point of transition in one’s journey towards the high altar and the shrine.