0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Full Well Ventures

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In this article from the October 10, 1923, issue of "The Outlook," magazine, Joseph B. Strauss discusses the state of agricultural production in El Salvador and other countries of Central America, the success of banana cultivation, cattle ranches, and coffee plantations.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

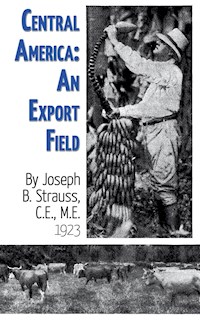

CENTRAL AMERICA — AN EXPORT FIELD

JOSEPH B. STRAUSS

Magazine article, “Central America — An Export Field,” by Joseph B. Strauss, C.E., M.E.

Originally published in the October 10, 1923, issue of “The Outlook” magazine

Modern Edition © 2022 Full Well Ventures

On the Cover:

Top Right: This gentleman is not trying to strangle an irate reptile—he is merely holding up a bunch of bananas for inspection: 26,000,000 bunches just like this one in the picture are shipped to the United States annually—a total of fifty bananas for every man, woman, and child in the United States.

BOTTOM: A portion of a herd of cattle on the ranch of Rafael Rodezno, the cattle king of Central America: With luscious fattening grasses imported from South Africa and Argentina, together with indigenous varieties, steers are fattened in from six to eight months. This makes cattle raising in Central America particularly profitable.

Photograph:

Coffee—one of the most important export crops in Central America: This illustration shows a coffee tree on a plantation in Salvador. Coffee raised in Salvador is of the finest quality, and nearly a hundred million pounds is produced annually. The proceeds from the coffee crop alone in 1922 were more than sufficient to pay off Salvador’s total indebtedness.

Created with Vellum

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Photograph

1

THERE is an undoubted revival of interest on the part of Central and South American countries in the economic welfare and the defense of the Panama Canal. This is probably due to the results of our combined fleet maneuvers of last spring which culminated in the theoretical destruction of the Canal by Admiral Eberle’s “Black Fleet.”

Lacking defensive island “vestibules,” the protection of the Canal depended upon the Atlantic Fleet’s watchfulness over both its eastern and western entrances. Anticipating the disposition of Admiral Jones’s Atlantic Fleet, Admiral Eberle was enabled to concentrate the “Black Fleet” around the Gulf of Fonseca and send attacking aerial forces over the route of the proposed Nicaraguan Canal, down the Caribbean coast to the Canal Zone, and over the Canal, where 264 dummy bombs were dropped upon the locks, and, according to the referees of the war games, the Canal was put out of commission for at least two years.

Here is, then, a weak link in our chain of National defense and a menacing factor to trade extension southward. For with the destruction of the Canal would come the fall of Latin American commerce, in so far as the west coast of South America is concerned, together with the possibility of the economic development of the Central American republics coming to a standstill. There is no question concerning the real value of the Panama Canal to Latin America, hence from an economic and defensive standpoint all Latin America is equally concerned with us in the maintenance and protection of the famous waterway.

When the Canal was completed and opened to traffic, a Latin American dream of four centuries' standing became a reality. Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, and Chile found the distance to European markets shortened by thousands of miles, and the west coast of Central America, previously cut off by the saw-toothed range of the Cordilleras, became an open market to the United States and Europe. From the trade standpoint alone North and South America have a common interest and a common problem in any canal across the narrow divide of Central America.