C C

C C

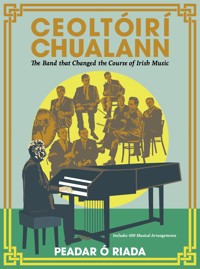

TheBandThaTchangedThecourseofIrIshMusIc

P Ó R

M P

Cork

www.mercierpress.ie

© Peadar Ó Riada 2024

ISBN: 978-1-78117-869-0

eBook: 978-1-78117-870-6

Cover design: Craig Carry

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library.

is book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including

this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information or retrieval system, without

the prior permission of the publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in the EU.

C

Foreword 7

The birth of a band 9

Index of the band’s list of arrangements 55

The arrangements 65

Discography 212

Scores 225

Miscellaneous pieces 239

Index 245

7

F

♫

I account of Ceoltóirí Chualann, I have relied upon the

extensive records of Éamon de Buitléar, Michael Tubridy and the family archives

here. I have had the good fortune that Seán Ó Sé has sat by my side constantly

advising and correcting the unfolding account. And until recently, I could talk to

Seán Keane regularly. I was very privileged to have grown up with, and known,

the band members of Ceoltóirí Chualann and to have counted them all, and their

partners, as our extended family.ere was a bond of love within this group that

extends to this day.ey were, and are, my friends.

I have assembled this account, and furnished as much detail as possible, so that

ordinary people may learn of the extent of their knowledge, innovation, ability and

courage.e idea that Sonny Brogan or John Kelly would take on complicated

scored arrangements may surprise some today. But they were very able musicians

with a wide understanding of music.ey also had great faith in my father, Seán Ó

Riada. He was a good teacher and could find unorthodox ways of explaining what

he needed.

People should also remember that the times they were working in were very different

to today’s expectations. Irish music in general was referred to as diddle-dee-di music

or only played in remote places. It was folklore. It was relegated to being something

of value for collecting and admiring. It was not generally tolerated in public houses

or in hotels.ere were notable exceptions of course but they were scarce. Ireland

was ‘modernising’. Electricity was entering more of the country’s human habitation

spaces. Younger generations now looked for a more exotic or foreign spark to their

entertainment.Television arrived during this period. Yet Ceoltóirí Chualann thrived

and innovated their way through these 1960s with great success.

When you read the arrangements, you will see that they are far more sophisticated

than mere accompaniment. I admit that I find it very hard to see anything comparable,

in the last fifty-three years, since they played their last notes.

Occasionally, over the years, we have assembled and played for special events.

Accordingly, as a member died and passed on, a close relative, or similar musician, has

8

taken their seat. I sat in for my father. We always use the original arrangements when

playing. I wonder if we will ever sit together again on stage, making music publicly.

I thank Mary Feehan, Dee Collins and Mercier Press for their interest and

assistance. My eternal thanks to Éamon, Mick, Seán Keane and Seán Ó Sé for their

help with this project, and to Eoin Ó Suilleabháin, Réamonn Ó Ciaráin of Gael

Linn, D. A. Duncan, courtesy of Irish Traditional Music Archive archives for the

Sonny Brogan photo, Liam O’Connor and Maeve Gebruers of ITMA, Michael

Scott, DMG Property Group and Emer Twomey of UCC Archives for help with

pictures and copies. I hope some of you readers find it of interest.

Beannacht Dé le h-anamnacha na mairbh.

P Ó R

An Draighean, 2024

9

T B B

♫

S Ó R grew up in a house where music was part of the background fabric

of life. His father, a fiddle player from Clare, was a sergeant in An Gárda Síochána

– the Irish police force. As a youth, he drilled and trained with Sinn Féin but

joined up with the new fledgling national police force, initially as a member of the

Dublin Metropolitan Police.e Irish state was in the process of setting up its own

institutions and this force was amalgamated into the new An Gárda Síochána.‘Seán

Ó Riada’ the elder (John omas Reidy) ‘passed out’ as a member of the first class

or intake on 23 June 1923. He had an uncle in the RIC, Michael Lernihan. Seán Ó

Riada’s mother, a concertina /melodeon player from the West Cork Gaeltacht Cill

na Martra, was a nurse and worked as a surgical theatre nurse under Dr Dundon

in the North Infirmary during the War of Independence in Ireland.While I think

her father Dan was a bit of a Redmonite, two of her brothers had to hot foot it to

Australia having been recognised during an ambush and a friendly RIC sergeant

cycled out form Macroom to Dan to warn him that the dreaded Tans were coming

to raid and pick them up. So my granduncles, Denis and Jim, left for Queenstown

(Cobh) immediately. Denis never returned but Jim came back briefly in the late

1960s.

Both John and Julia, Seán’s parents, sang around the house and danced if suitable

music erupted from the radio.ey were both good traditional set dancers and both

came from families where entertainment was based around the household and

visiting neighbours at night-time, which included card-playing, dancing, storytelling,

singing and music. Both came from agricultural backgrounds and were reared on

farms. Seán grew up in Adare, County Limerick where his father was sergeant for

twenty-eight years. He studied music from a very young age and became a member

of the Limerick youth orchestra of the time, and apparently was leader of the string

section by the age of twelve. He studied violin and piano. On going to university,

University College Cork, where he studied Classics first before changing to Music

under Aloys Fleischmann, he developed his interest in jazz and indeed made his

pocket money playing jazz in various bands.

10

He married at the age of twenty-two in 1953 and once qualified, that year,

assumed the position of assistant musical director of radio in the national radio

station – Radio Éireann.Towards the end of 1954 he went to England and then to

France in search of patronage or position to allow him to compose classical music. It

didn’t happen and he returned in the following early summer of 1955, and assumed

the position as musical director of the Abbey eatre. Whilst in this post he was

composing for orchestra and aslo composing choral settings for Radio Éireann.

His duties in the Abbey eatre meant he was heavily involved each year in

their annual pantomime in the Irish language. He also was in charge of providing

interval music and all other incidental music during or indeed before or after plays

on stage in this, the Irish National eatre. At the playwright’s request he assembled

his first vestiges of Ceoltóirí Chualann for the play e Song of the Anvil by Bryan

MacMahon. Bryan, an accomplished writer from Listowel in County Kerry, asked

Seán to provide a group of traditional musicians, as the sound backdrop to his play,

which opened for three performances on 12 September 1960.e full-length play

revolved around a fantasy story MacMahon created in a world and place called

the valley of Glensharon.e valley is under threat of an evil spell, that may be

cast upon it at any time, by a stranger. Emerging from the mist come a visionary,

a failed priest, a magician of the mysterious, two village nitwits and a sex-starved

spinster.e Lucht Sí (fairy folk) element gave the play a secondary title of e

Golden Folk. It involved fifteen dancers and Wren Boys and hence the need for

traditional players. Bryan had a great cast, as can be seen below, from the listing on

the play’s programme. With its cast of twenty-two, one can see many famous names

in the annals of Irish theatre in subsequent years:

Mooney, Ria – Director

Brogan, Harry – Actor as Mick Twin

Carroll, Bert – Stage Manager

Ó Guaillí, Éamonn – Actor as Garrett Gowa Fitzgerald

Long, Paddy – Actor as Dancers

Mac an Ailí (Fhailí), Reamonn – Actor as Dancers

Mac Anna,Tomás – Set Designer

Mac Cafraidh, Seamus – Actor as Dancers

Mac Cionnaith,Tomás P. – Actor as Fr ‘O Priest’ McHugh

Mac Leid, Pádraig – Actor as Crowd

Mac Seáin, Raghnall – Actor as Crowd

Ní Bhearain, Caitlín – Actor as Elenrose Schneide

Ní Bhrolcháin, Ester – Actor as Dancers

11

Ní Chatháin, Máire – Actor as Kitsy Carty

Ní Cheallaigh, Eadaoin – Actor as Crowd

Ní Dhomhnaill, Máire – Actor as Deborah

Ní Liodáin, Eithne – Actor as Dancers

Ní Mhurchú, Fidelma – Actor as Crowd

Ní Nuamain, Aingeal – Actor as Crowd

Ó Briain, Micheál – Actor as Paddy Twin

Ó Dubhlainn, Uinsionn – Actor as Walter Cunningham

Ó Floinn, Philib – Actor as Darby Jer. O’Shea

Ó Foghludh (Foghlú), Liam – Actor as Dancers

Ó Goilidhe (Ó Goilí), Seathrún – Actor as Crowd

Ó hAonghusa, Micheál – Actor as Crowd

Ó Luain, Peadar – Actor as Ulick Madigan

Ó Riada, Seán – Music

O’Sullivan, Clara – Actor as Dancers

Redmond, Avice – Actor as Dancers

Ryan, Patricia – Choreographer

R at the same time (opened 15 September 1960) in Amharclann

an Damer (an Irish language theatre on Stephen’s Green) was a play from Seán’s

e old Abbey eatre went on re in 1951 and the company moved to the Queens

where they performed until 1966.e eatre itself was demolished in 1975 and the site

now is one of Trinity College’s buildings.

12

pen entitled An Ceannaí Glic based on the death of the poet Eoghan Rua Ó

Súilleabháin. He assembled another small group of musicians for this play and when

he amalgamated both groups, he had Ceoltóirí Chualann.

Seán had become friendly with Éamon de Buitléar whilst purchasing fishing

and shooting equipment in Hely’s sports shop in Dame Street Dublin. He also

had a pet shop of his own.When he received Bryan MacMahon’s request Seán

spoke to Éamon about it and he introduced him to Sonny Brogan. John Kelly from

Carrigaholt in Clare was never far from Sonny and

Seán already knew him through his stint at Radio

Éireann.

Éamon de Buitléar became part of our lives

and acted as secretary to the band members for

Seán. He was married to Lally Lamb and she

would baby-sit us from time to time. She was calm

and quiet, very warm and gentle and I associated

her with warm homely actions such as baking and

knitting. She always had her hair in a bun. She was

from a very famous painting family (her father was

Charles Lamb) and worked in a shop selling books

and painting and craft materials and would bring

painting and colouring materials to us regularly. We

always looked forward to her visits.

Both she and Bernie Potts were the

‘advisers’ to the other girls or spouses to the

lads at practice sessions of the band. Éamon

seemed to be always dressed in native natural

materials such as tweed or báinín suits. He

spoke Irish or Gaelic always and was a very

interesting man and communicator. He and

Seán would discuss anything from nature,

fishing, history, interesting details of the

Náisiún Gaelach and the weekly progress of

our bee colonies.

Éamon was born in Galway where his

father was stationed in Dún Uí Mhaoilíosa

13

(Renmore Barracks) at the time. His father Col Éamon de Buitléar was aide-de-camp

to Douglas Hyde, Ireland’s first president. Éamon’s mother, a Waterford woman,

like her husband spoke fluent Irish and thus Éamon Óg de Buitléar was raised. His

father was a multi-linguist and a member of the Irish army intelligence unit.Éamon

was a truly committed environmentalist long before such a person was common. He

made many documentary films on Irish wildlife, published books and promoted the

language and culture in pioneering ways, including cartoons for young children. He

made a major contribution to Irish life and the nation during his life and will be

long remembered as the man who brought nature into our living rooms through the

television with his programme series Amuigh Faoin Spéir.

He knew Cúil Aodha pretty well having being sent there by his father to polish

his Irish. He stayed in Peaití Tadhg Pheig’s (Ó Tuama) house during those summers

so you can see there were circles of communication and community throughout all

our families and milieu.

Éamon played the accordion. In particular, my father would give him chords to

play in the band arrangements.ese were a new feature in Irish music at the time.

I remember my father explaining the sequence required and mapping it out, on the

floor in front of Éamon, in match sticks lined up in squares. I recall on one Sunday

evening during rehearsal, my father came up with an unusual arrangement for a song

called ‘Ding Dong Detheró, buail sin séid seo’ (Ding Dong Detherow, Beat this,

blow that). My father had the idea that the chorus would be accompanied by strange

sounds so we kids were sent off to find things that would make noise, if hit. I came

back with a green bottle and we found a USA biscuit tin box lid as well. Éamon and

Ronnie had to hit these items in a certain sequence to make a music ‘loop’ before

such things were even invented. You can hear this arrangement on the band’s second

LP called Ding Dong published by Gael Linn (1966).

Éamon was one of the rocks of my life until he died in 2012. He was what we call

in our own language a ‘Duine Uasal’ meaning a ‘Noble Man’. He was instrumental in

gathering the band together in the beginning and later did a lot of the organisational

work when Seán had moved to Cúil Aodha in West Cork. After Seán died, Éamon

formed a band called Ceoltóirí Laighean which also had John Kelly as a member.

♫

T hierarchy in Ceoltóirí Chualann of course.e Clare fiddle and

14

concertina player John Kelly appointed himself the

second in command, he always sat by my father’s

side. He gave opinions about all things musical and

had a gruff exterior. He was always right so my father

listened to him and was also involved with him in

other projects. John Kelly was the senior man in the

band and everyone listened carefully to what he had

to say.

John Kelly was from the townland of Rehy, near

Kilbaha, at the very tip of the western Clare Loop head peninsula. His father

Michaelandmother,Elizabeth Keane, were steeped in our native culture and

tradition. His mother was from Scattery island nearby and many a tune in today’s

repertoire originated there and arrived through John Kelly. He knew and played with

many iconic figures in the past of our great tradition – his uncle Tom Keane and

neighbour Patsy Geary were major influences, as were people like Nell Galvin who

knew Garrett Barry, the piper. John also recorded with the great piper Johnny Doran.

He moved to Dublin in 1945 and opened a hardware shop at the end of Capel

Street where you would find all kinds of useful things, including instruments – if

needed. As a child I used to be fascinated by the selection of ‘pen-knifes’, which I

coveted, but they were all under lock and key, under glass, along with a selection of

mouth organs. John married a Wicklow woman Frances Hilliard and they raised a

family who we became entwined with as we all grew up.eir older members were

slightly older than us Riada’s but we have always been close since that time. John was

one of the great traditional fiddle players of the twentieth century. In his youth he

diligently followed the music, no matter how difficult the journey might have been.

is trait he kept to the end of his life when he could be seen at a Stephan Grappelli

concert or instructing aspiring young fiddle players. His knowledge of the tradition

was a constant rich source for my father, Seán. Like everyone else in the band they

were good friends and he introduced Seán to many traditional musicians.

John Kelly’s side kick was the Dubliner Sonny Brogan who played the accordion

or box. Sonny worked as an elephant keeper in Dublin Zoo and used to complain

about their noisy racket. He suffered a little and would say ‘Me nerves are at me’.

He must have been married to a wonderful woman. I remember her as Margaret,

a small lovely friendly woman who would wave Sonny off with a gentle smile in

her blue kitchen smock with its red trim and flowery pattern. She always had Sonny

15

nattily and carefully dressed in a dark navy-blue

suit.ere was always a crease in the trousers

that could mow a lawn. His shirt was dazzlingly

white and the pinned collar was as stiff as a

plank and encased a red peacock patterned

tie that was carefully tied to perfection. He

was a great box player but would get nervous

when having to perform in the full glare of

the audience or in front of the radio or studio

microphone.ough born and bred in Dublin,

his parents hailed from the Kildare side.John

Kelly and himself were always sitting together

to one side of my father who would be at the

piano. I remember his sudden death in January 1965 and how it affected my father

when the news arrived.e members of Ceoltóirí Chualann were like a ‘Band of

Brothers’ and I saw Seán shed tears in our kitchen before heading for Dublin. He later

wrote of Sonny:

It was in the autumn of 1960 that I first met Sonny Brogan. I had been asked to supply

music for Bryan MacMahon’s play e Song of the Anvil at the Abbey eatre, and had

conceived the idea of using a group of traditional musicians for this purpose – the first

time, as far as I am aware, that such a step had been taken. It was Éamon de Buitléar

who introduced me to Sonny, who was at first rather shy and reserved, until he realised

what was wanted of him.e play went on and, though it did not find favour with the

public which it more than merited, the music seemed to succeed with everyone, not least

of all the actors and backstage staff, who used to be entertained by impromptu concerts

given by the musicians in the dressing rooms. Sonny was, of course, a prime mover in all

this and one of the reels which they used play most often backstage, commonly called

‘Redigan’s’, was re-christened by us privately as ‘e Abbey Reel’.

When the run of the play was over I hated the idea of parting from the musicians and

so formed ‘Ceoltóirí Chualann’, of which, during the few years we have been functioning

Sonny was a mainstay. I would not suggest for a moment that our association was all

sweetness and light. Many the argument we had – it is well known that musicians argue

more fiercely about traditional music than about anything else. However, we always saw

eye-to-eye in the finish and each argument served only to make us better friends.

Sonny’s qualities as a musician were rare. He had an astounding memory, so much

so that I was inclined to regard him, with John Kelly, as our living reference library. He

could recall three or four different versions of a tune going back through three or four

layers of time and often through three or four changes of title. He had a passion for the

pure, simple essence of tunes, uncluttered by mistaken ornamentation. He was also, of

16

course, an outstanding accordion player, one of the very few who could make it sound

suitable for playing Irish music.

As a person, Sonny was – well, he was contentious, convivial, argumentative, loyal,

dogmatic, witty, utterly reliable, a tiger when his temper was roused (which was rare), and

at the same time curiously gentle and courteous. He was a good friend. I shall miss him.

‘Beannacht Dé lena anam’. (Seán Ó Riada)

♫

A would sit at rehearsals in our sitting

room in Galloping Green, on my father’s other

side or righthand side, and in the window would

be the pipes and piper Paddy Moloney. He was

a young wiry Donnycarney,Dublin, lad with a

mop of fair hair. He worked as an accountant

in Baxendales, one of Dublin’s major hardware

stores. He was following his father’s footsteps in

that his father John had also been an accountant.

But it was his mother Catherine who bought

him his first tin whistle and started him on his

glittering musical path through life. He attended

the famous Leo Rowsome, who was his piping

teacher. It was at Baxendales that he met his fiancé Rita whom he later married and

they both raised their three talented children.

At rehearsals he would give out about the reeds in his pipes a bit but could do

anything he wanted to with the chanter, on which he was a true wizard. He also

played the tin whistle and was no stranger to the melodeon. I remember him courting

his wife Rita at rehearsals. He had a good musical ear so that he could be given contra

melodies and rhythms, which were a new phenomenon at that time. A good example

can be heard in the early track fromReacaireacht an Riadaigh– ‘Toss the Feathers’ (Ag

Scaipeadh na gCleití). Paddy later went on to form the group ‘e Chieftains’ who

have successfully travelled the world stage since then.is group initially consisted of

some of the members of Ceoltóirí Chualann and was augmented as the years went

by. In those early years most of their arrangements were Ceoltóirí material but since

then they have gone on to do many collaborations with many famous musicians of

other cultures, various genres and traditions. It is no exaggeration to say that his band

e Chieftains have become world famous.

17

e main tin whistle player in Ceoltóirí Chualann

was Seán Potts. Seán was a Liberties man, born and

bred, but his people originally came from Wexford and

for generations were one of Ireland’s iconic traditional

music families. As a kid I remember him as working for

the Department of Post and Telegraphs. I used to marvel

at the way his wide fingers could shape the sound of

his melody by exposing only fractions of a hole on the

tin whistle. It would always make and mark him, as the

‘standard’ on that instrument. His uncle Tommy was a

particularly innovative musician. Seán’s style on whistle is

instantly recognisable. But he also played the pipes. He had just married by the time I

got to know him. His wife Bernie Sanfey was the boss amongst spouses at rehearsals

and she and Lally (Éamon’s wife) would steer or advise the others who were either

courting or just married.ere was always great fun around them. Bernie is an ardent

Dublin GAA supporter while Seán’s roots are in Wexford. My father would often

give Potts the lead on tin whistle, in slow airs, because of his distinctive style.Seán

Potts later formed a group called Bakerswell, after he spent some early years with e

Chieftains. Once he came off the road with e Chieftains in 1979, he ploughed much

of his energy into Na Píobairí Uilleann, an organisation promoting Irish Uilleann Pipe

playing and music. In his time there it grew immensely and now has a fine premises

and a burgeoning following all over the world. Indeed, I have heard it said that you

cannot throw a stone now without hitting a piper. A very different world to 1960,

when I knew of only six practising pipers in all of Ireland. His tradition carries on

through his son Seán Óg who is also a good piper.

e third tin-whistle player was Mick Tubridy.

e longer in my life that I know Mick, the more I am

convinced he is the truest gentleman I have ever known.

He was the flute player in the band. He would come armed

with a paper bag of small liquorice multi-coloured sweets.

He was always smiling and quite spoken and gentle. He

wore glasses. He worked as a structural engineer until his

retirement in 1993. He was responsible for the structural

design of government buildings in Merrion Street,Dublin,

and of the passenger terminal buildings at Dublin airport.

18

In 1994, Michael was asked to re-design the Birr telescope before its reconstruction

in 1996–1997.

But his biggest task, as far as we kids were concerned, was to pass our test. As

the band would rehearse, we would get to know the arrangement and when each

instrument was due to join in that arrangement and play, we would wait until the last

second and pop one of the small sweets onto the embrasure or hole for blowing the

flute. Poor Mick would have to stick his tongue out and whip the sweet out of the

flute so that he could play on cue. We never managed to catch him out. He married

a fine step dancer called Celine Kelly of Gort a Choirce in Donegal.

Later in life they both developed a very strong interest in set-dancing and

traditional step-dancing.ey travelled the world teaching and were famous in

countries as far away as Japan. Celine passed away in 2017. Perhaps one of their

lasting legacies will be a wonderful book Mick published under the title A Collection

of Irish Traditional Step Dances.

Michael acted as a recorder of the arrangements and would write them out neatly

every evening as Celine went through the very extensive list. He was a founding

member of e Chieftains group along with Paddy,Seán Potts and Martin. He

retired from that group in 1979. I have never heard a raised voice from him or a

negative comment of any kind about anyone or anything. In later life I have found

him to be a fascinating companion when on dark winter nights at the end of a

session he starts reading the sky as we head for home.

e second fiddle player in those initial early days was one of Seán’s colleagues

from the Abbey eatre pit orchestra, Martin Fay. He worked at an electronics

firm, Unidare, but also did quite a lot of session playing

for the Gaiety Opera season, Mosney and so on. He

also married an Irish step-dancer and teacher,Gertie

McCormack. He had the great advantage, from Seán’s

point of view, that he was a professional musician and a

good music reader. is meant, in particular, that Seán

could give him sheet music with contrapuntal melodies

or harmonies. He also could play the viola, which gave

a greater depth to the strings, when required. Martin

also did a bit of acting for Seán in his ‘movie-making’

years. He was the suave, debonair member of the band

with a laconic kind of humour. Martin was the font of

19

many muttered jokes to the lads that would be inaudible to us young ones but would

always result in loud guffaws from the men. He never seemed to push himself ahead

of others and I have to say I was fond of him and in later years his quite manner and

kind smile were always considered an oasis of friendship.

Ronnie McShane was a fellow worker in the Abbey eatre and was a props

manager/maker when Seán was musical director. He was a McShane from Dublin

and as such he came from a rich theatre tradition, with both his parents working for

the Queen’s Royal eatre.is theatre, called the Queens by all, was situated across

the road from the Pearse Street fire station. Ronnie’s father was the very popular

caretaker and usher.ey lived next door to the theatre. Ronnie’s aunt Kitty was

married to the English actor Arthur Lucan.ey had a very popular mother and

daughter routine called ‘Old Mother Riley’ which appeared on stage and screen

regularly.e Queens had a who’s who of famous actors passing through at the time,

including the likes of Charlie Chaplin. Ronnie had two brothers and the three of

them attended the local St Andrews School where Ronnie was very popular with

his jokes and humour. When the Abbey eatre went on fire on 18 July 1951, the

company shifted over to the Queens.

When Seán Ó Riada arrived there in the summer of 1955 he immediately struck

up a friendship with Ronnie who became family to us. He was full of tricks and funny

stories and would always play and tease us. He was a kind of army style batman to

my father and always came to the rescue when something went wrong. I remember

at one stage a Hollywood film director,Stanley Kubrick, was coming to the house

in Galloping Green to meet Seán and discuss some

projects. Seán had by now been associated with the

film Mise Éire for which he provided the score. Seán

wanted to introduce Kubrick to the sound of Ceoltóirí

Chualann and decided that having them nonchalantly

playing downstairs in the basement, while himself and

Stanley conferred in the sitting-room overhead, was

the best method to engineer this encounter. But a drain

flowed underneath the basement floor.e room had a

big open fireplace in it and another room leading off. On

the Friday of the Kubrick weekend visit it rained from

the high heavens and the drain burst through the floor

until halfway up the basement stairs.

20

Mother was not amused and Seán sent for Ronnie. Calmness itself, he arrived

on his motorbike, assessed the situation, and called the fire-brigade – to pump the

place out. With the water gone, we all set about cleaning up the place and my father

decided that a fire should be lit to dry the damp floor and walls. No Hollywood

Indian smoke signals ever produced as much smoke and the place was still choking

all below decks, when Kubrick arrived the following day.e lads in Ceoltóirí

Chualann played away, below in the smoky pit, as ordered with pre-arranged signals

tapped by Seán’s foot on the floor above. I recount the story to demonstrate Ronnie’s

importance to Seán, the kind of unusual mix of people that flowed through the

house and the closeness of the band members to the family – they were our extended

family.

Ronnie was a very true and loyal friend of Seán’s and later followed him to Cúil

Aodha where he worked with him as a PA/batman/fixer and long-suffering guinea

pig for Seán’s different projects and schemes. Ronnie was always innovative and

would try anything. He had the sharpest beat on the bones of anyone I ever heard.

He was a willing experimentalist with Seán. He also made and prepared his own

sets of bones. A real Dubliner, always witty, he provided running commentaries for

various situations and even for arrangements such as the ‘Galway Races’ and the

‘Foilmore Drag hunt’. He married the wonderful Vera, and they had two great sons.

Seán Keane joined Ceoltóirí Chualann as a young man who my father described

to somebody as being as handsome as a Greek Adonis. He had entered a fiddle

competition in conjunction with theFleadh Cheoil an Radio series and had come to

my father’s attention. On winning the competition Seán asked him to join the band.

Seán Keane was born into a musical

family in Drimnagh, a Dublin suburb.

Keane’s mother and father were both

fiddle players from musical communities in

County Longford and County Clare. He

had a brother James who is no slouch on the

accordion as well. A brilliant musician he

pioneered the idea of technique associated

with traditional Irish fiddle playing. He

brought another dimension to the fiddle

section of the band, augmenting both John

Kelly’s rich traditional style, repertoire and

21

understanding and Martin Fay’s versatilityand ability.is tall fair giant of a man

is also a giant in the world of traditional Irish fiddle music. He has travelled the world

with e Chieftains.

He was married to a wonderful convivial woman Marie Conneally from

Ennistymon in County Clare but she sadly passed away in 2020. I think it is true

to say that her death, during covid lockdown, knocked the stuffing out of Seán.

Marie and Seán raised a musical family of their own in Rathcoole – a daughter

and two sons. He joined e Chieftains in 1968 and remained with them until his

death. He died peacefully and suddenly in his sleep at his home in Rathcoole in

early May 2023 and caught us by surprise and shocked us thoroughly. I had had a

long phone conversation with him days beforehand which started out about one of

the arrangements in this book but, as usual, wandered around the world for forty

minutes. He was a good friend to many traditional musicians around Dublin and

Clare and further afield and always willing to play a tune. He will be missed in

traditional Irish music circles for many years to come.

Peadar Mercier was the last member to join

the band. He did so during the mid to late 1960s

as bodhrán and bones player. I believe he was in

the original group playing in the Damer for Sean’s

play,AnCeannaí Glic, in 1960 but was called Paddy

rather than Peadar in the programme notes. My

abiding memories of Peadar are of his extraordinary

gentleness. He took over much of my father’s bodhrán

playing in the later arrangements as Seán concentrated

on the harpsichord. Peadar was a good Gaelgóir and married Nuala McGann from

Ennis, County Clare. She also sadly died in 2020. Peadar also played with e

Chieftains for many years and travelled the world with Paddy and the boys. Like

most of the Ceoltóirí, Peadar has been followed by his children into the world

of music and stage. His son Mel takes his father’s place when the band reforms

occasionally for special anniversaries.

efirstsinger chosen by Seán for this new fledgling band was Darach Ó Catháin.

Darach was born in 1922 on the Máimín in Leitir Mór west in Connemara but had

been moved as a youth in 1935, to the newly created Gaeltacht in Rath Chairn,

County Meath.e government of the time had bought up old estates and was

redistributing the lands to small farmers. As part of the movement, they set up