Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

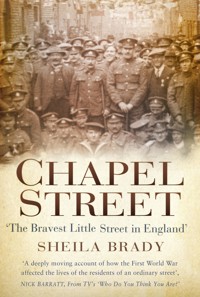

Chapel Street was a row of old Georgian terraced lodging houses in Altrincham, home to some 400 Irish, English, Welsh and Italian lodgers. From this tight-knit community of just sixty houses, 161 men volunteered for the First World War. They fought in all the campaigns of the war, with twenty-nine men killed in action and twenty dying from injuries soon after the war; more men were lost in action from Chapel Street than any other street in England. As a result, King George V called Chapel Street 'the Bravest Little Street in England'. The men that came home returned to a society unfamiliar with the processes of rehabilitation. Fiercely proud, they organised their own Roll of Honour, which recorded all the names of those brave men who volunteered. This book highlights their journeys through war and peace. Royalties from the sale of this book will help support the vital work of the charity Walking With the Wounded and its housing, health, employment and training programmes for ex-service personnel.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 495

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CHAPEL STREET

CHAPEL STREET

‘The Bravest Little Street in England’

SHEILA BRADY

Front cover: Courtesy of North West Film Archive at Manchester Metropolitan University.Back cover: Courtesy of Geoffrey Crump.

First published 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Sheila Brady, 2017

The right of Sheila Brady to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 863 35

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

To Dad

Our dad gave us the family’s verbal history of the First World War. It was a duty he took seriously. As children, he wanted us to have an understanding and to make it meaningful he took us to the towns, battlefields, cemeteries and memorials of Belgium and France.

We visited the memorials of the Menin Gate, for the last post sounded by the Belgian Fire Brigade; the imposing monument of Thiepval; Tyne Cot Cemetery, where we signed the visitors’ book and read the gravestones, and were informed of the work of the Commonwealth Graves Commission; and to Passchendaele, where he explained about Hill 60 and the Canadians’ sacrifice; we saw Ypres, Mons, Loos, Lens, Lille, Arras, Nancy, Verdun, Reims, and we followed the River Marne to Paris.

It was his legacy.

About the Author

SHEILA BRADY is a former local town councillor who has a degree in Education Studies. She formed a friendship with the author Dick King-Smith after finding out that her great-uncle was awarded the Military Medal for carrying King-Smith’s father through no man’s land in the First World War.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Preface

Introduction

Chapel Street: ‘The Bravest Little Street in England’

Ireland and Politics

Part One:

Lord Kitchener’s Letter to the Troops

Kitchener’s New Army

The Cheshire Regiment

Retreat from Mons

The Western Front: Second Battle of Ypres, 22 April–25 May 1915

The Battle of Loos: 25 September–13 October 1915

The Battle of the Somme

The Balkans Southern Front: Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF) Gallipoli Campaign

Salonika: 28th Division 84th Brigade

Salonika: 22nd Division 66th Brigade

Asia: Mesopotamia (Modern Iraq), Asiatic and Egyptian Theatre

Middle East: Sinai and Palestine Campaign (Gaza and Jerusalem), November–December 1917

Chapel Street Prisoners of War

Part Two:

Those Who Also Served

Part Three:

Compassion

The Commonwealth War Commission

Illness

Roll of Honour

Walking With The Wounded

References and Educational Resources

Appendix List

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the publishers The History Press and especially Nicola Guy, without whose interest in the manuscript and belief in the project, this book and its contribution to the worthy cause of the charity Walking With The Wounded would not have happened.

I am grateful for the kindness of Dr Nick Barratt who, when he heard about the book, instantly offered his help and support.

It is with gratitude and esteem that I thank the Chester Military Museum’s Andy Manktelow; Geoff Crump, who made me very welcome and offered all his resources, knowledge and expertise and with whom I spent privileged time; and Bill Preece, who showed me how to use the IRCS site and who found Martin DeCourcy, who was a prisoner of war, and James Ratchford’s heroic exploits; and Caroline as custodian of Peter Hennerley’s trove.

I wish to acknowledge Mr Paul Nixon’s site Ask the Expert, which I came across by chance and found an account of Private Vincent Maguire, and on further researching of records I realised that the name on the Chapel Street Roll of Honour was incorrectly recorded as McGuire. This led to a search for the DCM citation to ascertain the act of gallantry he was rewarded for. I also wish to make reference to Chris Baker’s Long, Long Trail site with its detailed information of the Royal Field Artillery Brigades and batteries. From here, I found the account of the German sinking of the British transport ship Kingstonian, which Vincent Maguire experienced and which enabled a search for the relevant dates and finding the written accounts of the event in the war diaries.

I would like to thank Jon Harrison from Cavendish Press for his offer of help. I especially would like to acknowledge the time and expertise of Will McTaggart, of the North West Film Archives, who was very helpful in facilitating the stills for the book cover and with accessing the Chapel Street Victory Parade film. A special mention is accorded to Wigan Local Studies, whose auspices are a model of local authority professionalism. I am obliged to Andy Burnham MP, the Lord Mayor of Greater Manchester, who offered assistance when he heard about the book and with the Walking With The Wounded fundraising efforts for servicemen.

Special gratitude is due to Tim Mole of the Salonika Society, who went out of his way to furnish me with the official Courts of Enquiry findings. Thank you to all the people who have helped in many different ways, they share in the success of the book.

Thank you to my friend Zainab Bhatti, who kept me going through the long, hard days and nights and whose encouragement and constancy is equal to none.

Special recognition and gratitude is due to my son Christian, for the original idea for the book and for its compilation, and whose support at every stage has been hugely invaluable,

If I have missed anyone from the acknowledgements or have made an error in research, please accept my apologies.

Preface

One day, many years ago, my father showed me a local newspaper article about the Norton family of Chapel Street, Altrincham. As he passed it to me he acknowledged it with the words, ‘Uncle Jimmy lived on Chapel Street.’ I read the article, which was about a family with several sons who had fought in the First World War. Up until then I had not heard of the street, and did not know until some years after this of its part in the Great War.

However, I was intrigued to try and piece together Uncle Jimmy’s military story. My father wrote down all the detail he could recall. We knew that Uncle Jimmy was awarded the Military Medal for saving an officer’s life, so I wrote to the Chester Military Museum’s Honorary Researcher and gave over the information we had. The researcher was Geoff, whom I met many years later whilst doing the research for this book. He sent me an account of a raid in Salonika along with detail, and a prisoner of war list.

It transpired that the officer whose life was saved was Ronald King-Smith. Acting on speculation, I wrote to Dick King-Smith, the highly popular children’s author responsible for The Sheep-Pig, the film version of which had just been released by Walt Disney as Babe. He confirmed that Ronald King-Smith was his father. After the war Ronald married, and Dick, an only child, was born. The year was now 1998, and for many years Dick and I enjoyed a warm correspondence, and he would send copies of his new books for my son Christian. One year, he sent a homemade Christmas card with a hand-drawn postage stamp on yellow paper, which I was overwhelmed to receive. It was a family tree of himself and his wife Myrle (who had just passed away), and his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, all drawn as matchstick characters. He was very proud of his family, and it was amazing to think that it was due to Uncle Jimmy’s heroic action that they were all born.

Some ten years later, I read that a blue plaque had been erected to the men of Chapel Street. Further enquires put me in touch with Mr Hennerley, who had been responsible for the commemorative plaque. We spent many hours chatting and laughing on the phone and he shared his reminiscences, including the fact that he knew of Uncle Jimmy. Peter Hennerley came from a military family background and close family members, including his grandfather, had lived on the street. He felt that the surface of the soldiers’ wartime experiences had only been scratched. He had also discovered the fact that the council had an obligation to keep the Roll of Honour in a state of good repair, in memory of the soldiers who had volunteered; an obligation which, up until that time, had not been honoured. Sadly, he passed away, and a booklet with his collection of memorabilia, recollections and history of Chapel Street was published in his memory, with the proceeds going to the local regimental benevolent fund.

In 2015, I came across a play of the First World War produced by the North West Drama Services Limited, in which Chapel Street was referenced. I contacted the director and was consequently invited to see the production, which involved north-west primary schools enacting roles and events telling the story of the war. I was informed that the children of Middlewich Primary (‘The Middlewich Pals’) were very interested in Chapel Street and wanted to ask me questions, and so a visit to the school was arranged. The children were very enthusiastic and knowledgeable; some of them brought in their family research and heirlooms, one pupil brought in a wonderful embossed cigarette box, a Christmas gift from Princess Mary to soldiers of the BEF. The visit went so well that my son suggested that I should consider writing a book.

I held on to this idea for a few months, then at Christmas 2015 I ran into Ed Parker, CEO of Walking With The Wounded, who was doing a sponsored walk to collect donations for veterans’ housing in Manchester. The charity was involved in a project that had purchased two Victorian streets and was renovating them to house ex-service personnel and their families. The project work had received a helping hand from the BBC One DIY SOS team, who filmed Princes William and Harry lending their services to the construction work. I thought, ‘this is a coincidence!’

I hope that the book will resonate with all those who read it. The story is a familiar one of its time. A hundred years ago, the men, women and children of Chapel Street did not get the help and assistance they needed after the war.

The legacy of Chapel Street is to ensure that returning servicemen and women and their families are looked after, and that their sacrifices are recognised and valued by society.

Introduction

When I started to research the men from Chapel Street, I found that it was a peregrination of discovery. Initially, I began by enumerating the names on the Roll of Honour, however, anomalies arose as the number of names recorded and the official total are not exact but correspond. It would seem probable that the date of the commissioning of the Roll of Honour is the reason for this. A further consideration in studying the names was the use of phonetic substitutes, the translation of names into English and the variance of accent; also, the creator of the record spelling the name the way they thought it should be spelled and transcription error; all of which was a complication in the census-taking.

One of the first areas of research undertaken was an examination of the 1911 Census. This is the official register taken every ten years, which lists all the names, marital statuses, ages, occupations and birthplaces of people who spent the night in each household, either residing or visiting on the nights of recording. I also had access to the Census documents for 1901 and the decades going back to the mid-1800s. However, one of the problems was the fact that anybody who lived on Chapel Street between 1911 and 1914 was not officially listed. As the housing was predominantly lodging house accommodation, this meant that boarders moved frequently. After the war, many men did not return to live in Chapel Street for various reasons, and it is probable that some returned to Ireland. To compound the issue, there is the difficulty of cross-referencing names; under the 100-year rule of confidentiality, the 1921 Census (three years after the war) will not be released until 2022.

The Roll of Honour, whilst recording the regiments and armies the men volunteered for, does not give battalion or service number information. Another major difficulty is the fact that only 40 per cent of soldiers’ service records or attestation papers survived the German bombing of the War Office repository during the Second World War. The attestation papers were either destroyed or suffered damage by fire and water, and became known as the ‘Burnt Documents’. This resulted in trying to find soldiers by other means, such as online searches, which entails searching: Silver War Badge records, pension records, medal index cards, prisoner of war lists (many prisoners were not listed), Commonwealth war graves, Soldiers that Died in the Great War (SDGW), medal citations and anything else that might help.

War diaries are another search area. However, as the diaries are effectively the recording of events in the field of action, it is worth knowing that ‘Other Ranks’ are generally not mentioned by name, though officers may be. Not all the regimental or unit war diaries are digitised, for example those pertaining to Mesopotamia and Macedonia (Salonika), which can limit research. These diaries can be viewed, however, at the National Archive (Kew), which necessitates travelling to London. It may be that a personal visit to the relevant Regimental Military Museum would yield information from the battalion diaries; this would require an appointment. It is worth enquiring if the museum(s) are open or have changed address beforehand. For instance, at the time of writing, the National Army Museum has just opened after refurbishment, but an in-depth study of the Royal Horse and Field Artillery including the Royal Garrison Artillery could not be carried out as the museum at Woolwich has closed and is in the process of transferring to Salisbury; as is the Royal Marines Museum and the Royal Engineers Museum. This circumstance also affected the research of other regiments pertaining to Chapel Street. Whilst some museums keep material online, others do not, using this tranistional phase as an opportunity to develop the sites. Unfortunately, regimental museums do not keep lists of the soldiers who served with them, though some are endeavouring to do this along with the histories of individual service, relying on volunteers to carry out research.

Another factor to consider is that soldiers can change their battalion or regiment, as many of the soldiers did, either through manpower shortage or returning to battle after injury. Brigades and divisions also changed for differing reasons. If soldiers served in the Labour Corps they could be attached to different regiments, and this can present difficulties with the complexities of service number identification, especially if searching for a common surname such as ‘Smith’. It is also worth noting that second names can be used instead of first names, which is a common custom in Ireland, i.e. ‘Patrick, James’ for ‘James, Patrick’.

It can be useful to use a Soundtex converter when searching for difficult to find surnames. Soundtex is a system universally used to search through a phonetic index for names that sound alike but are spelled differently, such as Stewart and Stuart, and for names spelled with different vowels, or double letters. Soundtex tools are freely available online, and genealogy websites such as Ancestry and Find My Past now have free access at most libraries.

Another avenue to explore is the Local Studies centre in libraries, along with newspaper searches. It can be very useful to have a membership of societies and/or associations, and to engage with forum sites.

The book contains a large amount of easily accessible educational material and resource links useful for teachers, educators and students in their study of the Great War. It is hoped that study of the narrative accounts will lead to the development of frameworks for further research and debate, and so to the deepening of our knowledge and understanding of the experience of the First World War.

There is more archival material available for research to the enthusiast than there has been previously, and I am personally very excited to find out the part the men of Chapel Street played in Russia; and the two-day march across the Sinai Desert undertaken by the 127th Brigade during the Battle of Romani, in defence of the Suez Canal from the Turks, which resulted in victory; and a telegram of praise from King George V.

It is amazing what can be revealed, as I hope the reader will appreciate from this account of the ‘Bravest Little Street in England’.

Chapel Street: ‘The Bravest Little Street in England’

At the outbreak of the First World War, Chapel Street stood as a long row of sixty Georgian and Victorian terraced houses in Altrincham, Cheshire. From here, 161 men heeded Kitchener’s rallying cry and volunteered to fight for ‘King and Country’. King George V, recognising their patriotism in a telegram, was moved to call it: ‘The Bravest Little Street in England’.

In 1914, Chapel Street was home to some 400 men, women and children, mostly of Irish nationality and English heritage. The historical roots of this conurbation are largely unknown; however, there was a definite Irish presence in Altrincham in the latter eighteenth century. Probably this was due to the political and religious situation in Ireland at that time, and the conditions and penalties placed on the Roman Catholic population by the Penal Laws. These extreme laws prevented Irish Roman Catholics from intermarrying with Protestants; purchasing or leasing land; voting or holding political office; living within 5 miles of a corporate town; entering a profession; or obtaining an education. Ireland was part of Great Britain at this time and was benefitting from an expansion in its economy. However, in view of the imposed sanctions, disenfranchised Catholics may have considered it more expedient to leave the country and become economic migrants in a more tolerant society. This could have coincided with the employment and construction opportunities afforded by the building of the Bridgewater Canal in 1760, and its extension to Altrincham in 1765. In 1774, a new Act of Parliament removed the restrictions imposed on the textile trade. And by 1782, a new mill had been built and was locally auctioned with the claim, ‘Plenty of hands to be procured in Altrincham for carrying on the cotton manufactory and on very reasonable terms’ (Foster: 2013). Evidence indicates there were four mills in Altrincham by 1800. The 1801 census records the population as 1,692, and 340 houses.

Catastrophe struck in 1845 with the failure of the potato crop in Ireland, which was a recurring event from 1739, happening some eighteen times and leading to the potato to be recognised as an unreliable crop. This was a widespread blight coupled with poor weather conditions, leaving the Connaught area of Ireland the worst affected. The potato was a staple part of the Irish diet and was also grown for export to England. It set off a chain of events that led to disease, starvation and death amongst the population. During this time people lost their income and the means to pay rent, which led to evictions and homelessness. Families were left destitute, relying on workhouses and poor relief. The Poor Law had been extended to Ireland in 1838. From 1845–52, the population dropped by some 2 million. As more than a million people died from hunger, it came to be known as ‘The Irish Potato Famine’, or Gorta Mor (The Great Hunger). Many Irish leaders and orators saw capital being made from the disaster by landowners using it as a means to increase their lands, and the authorities using it to subjugate a rebellious population. They argued that food exports should be curtailed to feed the home population. At this time, Britain operated a protectionist economic system known as mercantilism. Though Ireland was part of the Union, it was at the same time considered to be a foreign country, therefore subject to tariffs. Under the Corn Laws, exports of grain were kept artificially high, and ‘corn’ was deemed to be any grain that could be milled, especially wheat. In practice, this meant that bread, another staple food, was beyond the reach of most. The Anti-Corn Law League sought a repeal of these laws, but this was not a popular political policy and was not immediately enacted. Exports to England increased during the famine and grain was plentiful. Consequently, ‘Dissenters’ believed it was a deliberate policy of genocide imposed on the population by the English. It was the cause of mass emigration to England, the USA and Canada by those who could escape its consequences.

A sea-swell of Irish arrived in England, and by 1851, Altrincham had a recognised Irish community with over 200 living in Chapel Street. Although this ingress of Irish immigrants was British, they spoke a different language (Irish Gaelic), and were regarded as foreigners; they were also seen to be politically dangerous. Altrincham during this period of time must have seemed a good prospect. The railway linking it to Manchester was under construction in 1846, opening in 1849. Work was available and Manchester was at the heart of the now thriving cotton industry. Opportunities for employment and a new life away from the countryside came with this first wave of industrialisation. The Chapel Street immigration was mostly from the counties of Mayo, Galway, Sligo and Tipperary (Connaught). These western counties were devastated by the failed potato crop, and lack of investment in constructive infrastructure and productivity. Passage from Ireland would have been from the ports of Dublin or Belfast and most would have been foot passengers, i.e. not reserving berths for the three-hour crossing to Liverpool. They would have had little luggage and relied on purchasing supplies on arrival. It was a diaspora, and entire families were leaving their roots behind.

The Irish brought with them their culture, and by all accounts Chapel Street was a very lively and industrious society. Chapel Street gained its slightly ‘S’ shape due to the apportioning of former agricultural strips of land which were sold off as building land (Bayliss: 2006/7). Terraced housing was ideal for housing large numbers of people (1820–40). A cartographic survey shows a combination of mixed housing ranging from groups of terraced houses, three-storeyed terraces, some back-to-back houses and semi-detached housing with stables, and included in this were sixteen cellar dwellings. The street was built on a slope, and photographs of the time indicate there were no gardens, trees or verges; the unpaved street was very narrow, approximately 11ft in width. Some of the houses had steps outside. The street was lit by a couple of gas lamps affixed to the walls of buildings. There was a general provisions store, a bakehouse and piggeries behind the housing, with a sizable market garden or allotments. A variety of trades and labour were employed by the residents, including lodging house keepers, coachmen, gardeners, labourers, railway workers, stonemasons and nail-makers. A contemporary account states that every house in Chapel Street had a handloom. Schooling provision for ‘scholars’, as the children were known, and place of worship was on a nearby street, formed by converting two cottages. St Margaret’s Church opened a tea and coffee house at number 19, which proved very popular, leading to another property being purchased. Here, residents could read newspapers and books, and there was a smoking room. In 1880, number 42 was bought as a refuge. Here, religious, moral and industrial teaching was given to ‘all children who are unprotected, or in circumstances of degradation’. At the top of Chapel Street stood a Wesleyan Chapel where John Wesley preached in 1761. It was sold in 1881, with some 512 square yards of land and erected buildings, and was described as one of the most valuable and improving areas in Altrincham. It was now known as the Congregational Church. There were two public houses: The Grapes (still standing under a different name) opposite the church, and The Rose and Shamrock situated in the middle of the street, which was the centre of activity. Here, everybody came for their socialising, drinking, music and entertainment; not least of which were the regular fights that broke out. Such was the reputation of the strong and resolute men that lived and drank there, that the local priest was sent for when things got out of hand.

In the 1800s, life was precarious and in Altrincham the mortality rate was high, outbreaks of typhus fever and cholera were an annual occurrence. The town had its own local Fever Hospital paid for by charitable means. Dysentery and other associated ailments were difficult to contain or eradicate. In 1852, Sir Robert Rawlinson was commissioned with presenting a report to the General Board of Health. This would be a preliminary inquiry ‘Into the Sewerage, Drainage and Supply of Water, And the Sanitary Condition of the Inhabitants of the Town’. As part of the inquiry, a cartographic plan of all land and property in Altrincham and the surrounding areas would be drawn, to enable a local board to judge the propriety of applying the Public Health Act to the town and township of Altrincham. The report was exceedingly scathing in its findings, and it noted: the want of proper sewage, pavement and cleansing; the neglected state of the town and the dirty, unpaved, undrained and ill-ventilated squares and alleys; the faulty arrangement of cottages, yards and midden sand privies. Chapel Street itself was serviced by communal privies, midden, a few hand pumps and sink stones; there was also a long alley for drying washing running at the back of a block of houses. In submitting evidence to the inquiry, local working men from Chapel Street complained about the want of water and Mr Balshaw, a local builder, stated that he could not let ten new houses he had recently built on the street because they had no drainage. Another contention was the issue of keeping pigs close to housing stock. Rawlinson states to remove them forcibly ‘would be resisted to the uttermost and would result in the Irish admitting the pigs as inmates’. Alarmed by this possibility, he states that other diseases such as malaria would be rampant in the town if this happened. Rawlinson was also unhappy with the overcrowding in the lodging houses, with the inquiry revealing four to ten beds in one room as commonplace. Rawlinson’s proposals were accepted, not least of which was the establishment of a proper form of local government, proper sewers and drains would be constructed, a sufficient supply of pure water, and the paving and regulating of all streets, courts, alleys, lanes and passages liable to be used by the public. The number of houses on Chapel Street depleted from about this time from eighty-one houses to sixty, presumably as part of the sweeping proposals.

By the 1850s, Liverpool had developed as a port of strategic importance. From here, imports of cotton from India, the Middle East and the southern states of America made their way by the canal system to the mills of Lancashire. Manchester became known as ‘Cottonopolis’, and cloth spun from the cotton was exported to the Empire. It was said that Britain clothed a quarter of the world’s population. But this was about to change. In 1860, Lincoln was elected President of the United States of America. However, because of his stance on the slave trade, seven southern states seceded to form a new nation: the Confederate States of America. By 1861, America was embroiled in what came to be known as the American Civil War: the Union (north) against the Confederacy (south). In April 1861, President Lincoln ordered a military blockade of the southern ports in order to prevent the export of cotton. He sought to starve the Confederacy of its income, which was financing its war effort. He justified his actions on the international stage on the grounds of humanitarianism, and called for the abolition of the black slave trade, which was used extensively in the south to pick cotton. If the Confederacy was to succeed, it needed support and recognition from Britain and France. The Confederate Congress believed that the way to remove the Union Blockade was through ‘King Cotton Diplomacy’, a cotton embargo. By limiting supply, it sought to upset the economies of its trading partners and put pressure on them to join in the fight against the Union. Diplomatic envoys were sent to London for meetings with Earl Russell, then Foreign Secretary, who was a strong advocate of laissez-faire, an economic system which is devoid of government interference such as embargos or sanctions, the opposite of mercantilism. Indeed, a decade earlier, as prime minister, he would not intervene during the Potato Famine regarding the exportation of food to England, preferring to let free trade take its own course.

The plight of the black American slaves of the Deep South struck a chord of solidarity with the millworkers of Lancashire, many of whom were Irish. They also had experience of being tied to autocratic landowners as economic slaves earning a potato wage; that is, earning just enough to cover sustenance and possibly rent for themselves and families. This was known as the cottier system (a peasant form of serfdom, which disappeared from Ireland altogether). They wholeheartedly supported the blockade of raw cotton by President Lincoln and refused to spin cotton. Another reason was probably the recognition of democracy and a government elected by its people. Ireland’s own parliament was dissolved in 1800, and its governance came from Westminster, and though it had representation by MPs, its people did not have a free vote. Manchester had been at the forefront of demanding electoral reform with the Chartist Movement and the Reform League. These active organisations had great support from the millworkers, who demanded representation (the majority of working men did not become enfranchised until 1867). In 1863, President Lincoln wrote a letter to the working men of Manchester, in which he reiterated his terms of office stating that his government was one of integrity, founded on human rights. He argued that it should not be substituted for one which should rest exclusively on the basis of human slavery. He emphasised the values and sentiments of justice, humanity and freedom and acknowledged the sufferings the struggle had caused, stating that: ‘Theirs was an act of sublime Christian heroism, which has not been surpassed in any age or any country.’ This was indeed a time of struggle. ‘King Cotton Diplomacy’ had not worked; Britain did not give formal recognition to the Confederacy and maintained a position of neutrality, despite many manufacturers in Liverpool and Manchester demanding that it should be recognised. The consequence of this was a depression. Stockpiles of raw cotton lay in full warehouses. The price of cotton fell rapidly, and a loss of markets and idle looms all over Lancashire caused a situation which became known as the ‘Cotton Famine’, lasting from 1861–65.

When the Poor Laws were drafted, the Poor Law Commission did not take into account the situation in the north or the socio-economic effects of recession. The consequence of this was that the slump in cotton production meant thousands of people had no work or income; families had no breadwinner or means of paying the rent and buying food. The law that was intended for vagrants, beggars and ne’er-do-wells was now applied en masse to a population that had no control over the economic situation. This situation was mirroring the humanity crisis in Ireland. Richard Cobden MP (Anti-Corn Law League) stated that the cessation of employment represented the loss of £7 million per annum in wages. He saw this as a crisis which warranted national attention, and for which local poor relief could not meet demand. In England, the welfare provision for the poor was in two forms: the Outdoor Relief, which was administered by local charities, offering money, food, clothing or goods; or the state’s provision for the absolutely destitute: the workhouse. Poor Law Unions were formed from small parishes coming together to build workhouses. Under the Poor Law system, they were paid for by levying a ‘poor rate’ on property-owning middle classes. Conditions of entry to the workhouse were dire; they were not to be seen as a soft option. In return for bed and board, the inhabitants did long hours of menial work. It was a humiliating system of degradation which included the segregation of whole families. Many poor people died in them from hard labour, illness and simply losing the will to live. The result was that people avoided them at all cost, which was an intended prerequisite of their provision. A codicil to the Poor Law was ‘The British Laws of Removal’. This was a sectarian piece of legislation which was intended to reduce the burden on local rate payers. Irish people were required to have a residency period of five years before they could claim poor relief. The stipulation was that those who did not meet this requirement no longer qualified for residency in the country, and under magistrate’s order they were forcibly returned to the original port of entry, and from there back to Ireland. The letter of the law regarding forced repatriation was loosely interpreted and Irish nationals of even longer residency found themselves stranded on the dockyards of Ireland. Essentially, the Irish poor were deported, and this would have applied to Chapel Street. Records for 1860–62, show regular expulsions from Altrincham to Ireland until 1875. lreland was also in the grip of depression, with 1879 being a marked year for failed potato harvest, and another famine known as ‘Gorta Beag’ (mini famine). Although not as severe or long-lasting, and with relief in place, it nevertheless was a testing time for government and people causing unrest and consternation. A determined populace was not prepared to tolerate an English absentee landlord system, increased rents and evictions, and the income of these rents transferred to England. The Land League of Mayo was formed by tenants and it rapidly became organised as a protest party as membership increased, its title changing to the Irish National Land League.

Emigration also increased in that year, and many Irish came to Chapel Street. From 1871–81 the population of Altrincham in general rose by nearly 3,000. There were many reasons why populations moved around, such as war, displacement and employment.

Onomastic research reveals many surnames of the residents to be a mix of: Italian (Venice – Margiotta); Anglo-Saxon (Bagnall, Clarke, Oxley, Reeve, Wyatt); Old English (Barrett, Stocks, Starrs); English (Croft, Kirkham, Morley, Peers, Ratchford, Smith, Taylor, Turton); Old French/Welsh (Hughes, Caine); Anglo- Norman (Burke, King); Norman French/Germanic (Hulmes); English/German (Arnold); German/Irish (Lennard); Irish Gaelic (Kenny, Brennan, Murray, Naughton, Quinn); Anglo-Scottish (Johnson, Wood); Welsh (Jones, Owen, Prosser); Irish (Behen, Collins, Curley, Durkin, Dwyer, Egan, Gormley, Groark, Hanley, Kelly, Mahone, Riley, Rowan, Ryan, Scanlon, Sheehan, Shaughnessy); and Old Norse (Scarfe, McNicholas).

Habitational names such as the surname Hollingworth, taken from an area in Lancashire (Old English for ‘hole and enclosure’), reveal how far populations move around, as do surnames specific to certain areas such as Corfield, indigenous to Shropshire; as well as pre-medieval location names such as Featherstone, and local derivations such as Brownhill, believed to have come from nearby Sale in Cheshire in the late thirteenth century.

Many of the surnames reveal a royal lineage or aristocratic hereditary, such as Tyrell, a baronial name from Castleknock; Wickely, from the family seat at Brampton; Birmingham, who accompanied Strongbow to Ireland; Chesters, mentioned on the pipe roll between 1119 and 1216; Davis, a patronymic surname for the last independent ruler of Wales, Dafydd ap Gruffydd; DeCourcy, from the Carolingian Kings of France; O’Connor, considered the most important of all Irish surnames, an aristocratic Catholic family who were the historic Kings of Connaught; Hannon, from the Clan Hannon, associated with the Counties of Limerick, Galway and Roscommon and who, it is said, gave the names to Eire and Ireland.

Endogamy, the practice of marrying within a specific ethnic group, class or social group and keeping distinct as a community, was a custom of Chapel Street. Families intermarrying included: De Courcy, Oxley, Hennerley, Booth, Inion, Donnelly, Hanley, Hollingsworth, Shaughnessy, Brennan and Tyrell.

Capital investment came to Liverpool and Manchester in 1887, with the construction of the Manchester Ship Canal which would link Manchester to Liverpool, and via the Irish Sea would open a trade gateway for imports and exports with the rest of the world. It would bypass the railways and their charges, and merchants would benefit by avoiding dock and town duties at Liverpool. It was also a response to ‘the Long Depression’ (previously known as the Great Depression) of 1873–79, and was caused by the second wave of industrialisation. There were 12,000 workers employed on the 36 miles of excavation, rising to 17,000 at its peak. It is likely that the single men coming from Ireland and living in lodging houses in Chapel Street would have formed part of the workforce. Likely they would have been enlisted or recruited by ‘gangers’ on behalf of the company. These migrant men were known as ‘navvies’ (often used as a derogatory term) or navigational engineers. Historically they worked on railway construction, and then on canals. The work of the ‘navvy’ involved more than a man with a pick and shovel; essentially, this was an overarching term which involved the subtrades of drilling, mining, hammering, timbering and handling explosives. It was difficult and dangerous work and many lost their lives. Victorian enterprise was extended further in 1897: three years after the canal opened, its consociate, Trafford Park, began development to become the world’s first planned industrial site.

This was also the age of Empire and world events would draw the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland into war against the Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State, known as ‘The Boer War’ (1899–1902). Records show that more men enlisted from Chapel Street than any other street in England, and they distinguished themselves with honours. The reasons for this can be speculated on: it is possible that the population explosion in Altrincham, with an increase from 4,488, in 1851, to 16,000 in 1900, and the short supply of jobs and income, were contributing factors. Since 1800, recruitment into the militia by the Irish was a known occurrence in times of economic decline. The Census for 1891 records single men from Knutsford taking abode in lodging houses on Chapel Street (the local workhouse was situated in Knutsford). Patriotic fever was running high in the country, with parades and marching bands in Altrincham including a visiting American brass band. The year 1887 had seen a popular royal visit to Altrincham by TRH Prince and Princess of Wales to mark the occasion of the Jubilee of Queen Victoria. It should be noted that in 1900, Queen Victoria had a very successful trip to Ireland, and it was thought that the long-awaited permanent royal residence would go ahead. It was also a time of sentiment and many Irish felt that her presence would bring about a new golden dawn of prosperity, enabling a return to the mother country.

Altrincham celebrations for the Coronation of King George V, 1911. (John Hudson)

In 1913, Altrincham held a by-election which saw the Unionist candidate George C. Hamilton easily win the contested seat with an increased majority. Hamilton was a local employer who would not pay union rates. Another controversial issue was Home Rule for Ireland. Many people living on Chapel Street at this time were born in England but had Irish heritage, and the Irish Nationalist leaders John Redmond and T.P. O’Connor were urging Irish voters to vote for the Liberal candidate. The Liberal Party had formed a minority government with the support of the Irish Nationalists, and they were attempting to introduce Home Rule for Ireland. At the time of the election there were concerns regarding the issue of plural voting (electors who appear on the electoral register twice), which both parties recognised and this may have influenced the outcome. Hamilton held the seat until 1923, when there was a swing to the Liberals.

George C. Hamilton was appointed Director of Enrolment National Service in 1917 (National Service is compulsory service: or Conscription).

In 1914, Britain declared war on Germany in response to the guarantee given to Belgium to protect its neutrality in the face of invasion. Germany issued an ultimatum to Belgium to allow free access for its troops to pass through the country to go to war against France. Belgium rejected this ultimatum. On 3 August, Germany declared war on France, and on 4 August, Britain was at war with Germany. This was a national call to arms. The reasons for volunteering can be speculated on. Public records show the population of Altrincham had now increased to approximately 18,000, and work and wages were still a primary concern. By 1914, evidence shows nearly half of Chapel Street was given over to lodging houses. In 1916, when the war was at its height, lodging houses at numbers 3 and 5 Chapel Street were sold as ‘viable investments’, attracting a letting income each of £26 per annum (in 1901, Welsh tenants made up a third of lets), and half of the male occupation worked as labourers of various sorts. However, war in Europe was different and invasion was a real threat. This time it was about peace and security, principle and values. Germany was seen to be ambitiously expanding its empire. Genuine patriotism and a feeling of protectionism were valid reasons to go to war. In addition to this was the urging and blessing of the Catholic Church in Britain and in Ireland, notably the Bishop of Galway and the Archbishop of Tuam (part provinces of Galway, Mayo and Roscommon), for men to enlist to fight against Germany. This was in retaliation to the devastation of Leuven, Belgium, where the oldest Catholic University in the world and its manuscripts were destroyed by the Germans. Leuven had enjoyed a close association with Ireland for centuries, and was the seat of the first Irish language institute. It was an attack on Irish heritage, religion, culture, identity and history. The Bishop of Kildare stated it was the duty of all faithful Christians to come to the aid of what was now essentially a Holy War. Playing on this attack of Ireland, and the empathy of nationalism towards a small country invaded by Protestants, the British War Office recruitment posters urged Irishmen to answer the call and come to Catholic Belgium’s aid.

In August 1914, there was a political crisis in Ireland which threatened Civil War. The passing of the Government of Ireland Act 1914, which became known as the ‘Home Rule Act’, divided the country. Nationalists were in favour of independence and were largely Catholic. They wanted the restoration of an Irish parliament with distinct powers. The Unionists wanted to stay in union with Britain and drew on Protestant support. The implementation of Home Rule was postponed under the Suspension Act 1914, for twelve months, due to the outbreak of war. The war was generally acknowledged to be of short duration and the act had reached the statue books by September 1914. John Redmond MP, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), used political coercion to project the idea that militarily supporting Britain in its hour of need, in the form of enlistment, would strengthen the case for devolvement. This was widely supported by most nationalists in Ireland and could have been an influential factor in the enlistment of Chapel Street.

Eighty-one men volunteered for ‘King and Country’ on the first day of the war. Lord Kitchener’s highly provocative poster doubtlessly was persuasive in stirring the emotions of the other eighty men. Some of the men of Chapel Street had previously fought in the Boer War and were decorated soldiers; to them, Kitchener was a heroic and valiant figure who had led them to victory at Mafeking. And he was an Irishman: a fellow countryman who could be trusted. With the ethereal finger pointing and the mesmeric stare giving a sense of urgency, the poster ‘Britons: Lord Kitchener Wants You. Join Your Country’s Army!’ would have been a calling impossible to ignore. The poster sought to create a feeling of individual worth and a sense of collective nationalism, as well as a response to an emergency cry for help. The gravitas of the end line, ‘God Save the King’, to many would have seemed like the response of a bidding prayer: a prayer to God. Chapel Street answered the call-up and its husbands, fathers, sons, brothers, uncles, cousins and fiancés volunteered for ‘The War to End All Wars’.

BUCKINGHAM PALACE

My message to the Troops of the Expeditionary Force. Aug. 12th, 1916.

You are leaving home to fight for the safety

and honour of my Empire.

Belgium, whose country we are pledged to

defend, has been attacked and France is about to be

invaded by the same powerful foe.

I have implicit confidence in you my soldiers.

Duty is your watchword, and I know your duty will be

nobly done.

I shall follow your every movement with deepest

interest and mark with eager satisfaction your daily

progress, indeed your welfare will never be absent from

my thoughts.

I pray God to bless you and guard you and bring

You back victorious.

Ireland and Politics

In 1914, the peaceful achievement of Home Rule for Ireland was thrown into doubt due to the failure of the Government to deal with the build-up of arms in Northern Ireland (it was estimated that the UVF [Ulster Volunteer Force] had smuggled in from Germany 24,600 rifles and 3 million rounds of ammunition; with the Nationalists also smuggling in from Germany some 900 rifles and 25,000 rounds of ammunition) and the public refusal of a cavalry brigade in the Curragh to enforce the Home Rule Act. Civil war in Ireland was looking increasingly inevitable, but was prevented when the First World War broke out.

Great War

When Great Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, the total army strength was 247,000 with 145,000 ex-regular reservists. Of these, 20,000 were Irishmen already serving in the regular British Army with another 30,000 in first line reserve.

The British Army did not have National Service or any form of conscription and relied on volunteer soldiers. When war was declared, Lord Kitchener, who became Secretary for War on 5 August 1914, informed the Cabinet that it would be a three-year war requiring at least a million men. The attestation papers that volunteers for the war were required to sign stated that it was a short attestation. However, these facts are contrary to the popularly held belief that the war would be ‘over by Christmas’.

Thirty new divisions were incorporated into what became known as the ‘New Armies’ or ‘Kitchener’s Army’. The volunteers were assigned to new battalions of existing regiments of infantry with the word ‘Service’ added to the battalion number. When volunteer numbers began to dwindle conscription was introduced, but this was not applied to Ireland.

On 20 September 1914, the leader of the Nationalist Party, John Redmond, was widely expected to be the first prime minister of the new Irish parliament. He called on the ‘Irish Volunteers’ to enlist in the British Army. This created a schism within the organisation, which resulted in those following Redmond (approximately 168,000) changing their name to the National Volunteers. The remaining 12,000 retained the title of the Irish Volunteers (erroneously referred to as Sinn Fein Volunteers), and committed themselves to the objective of gaining full independence for Ireland, by force if necessary.

John Redmond, the leader of nationalist Ireland, was a consummate politician of persuasion: a man ahead of the game. He understood the need for popular support and financial donation, and the need for powerful political allies to the cause. He astutely combined this in declamatory speeches that drew on nationalism, patriotism, Catholic ideology, sentimentality and love for the ‘old country’, global identity and a unity of ‘Irishness’ and what that meant. On 17 March 1914, St Patrick’s Day (a celebrated day of national holiday for Irishmen and their descendants), American President Woodrow Wilson sported a sprig of shamrock in his jacket buttonhole. Redmond’s gifts of pots of shamrock were on display in the White House and around Capitol Hill. Reports of the time stated that big dinners, balls and gatherings were held, with some 3,500 attending Mass at St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York.

Some five months later, however, the First World War had broken out. It was, as the Americans say, ‘a game changer’. Redmond still believed in the ideology of an Ireland that would gain its freedoms and identity, from within the provisions of the Home Rule Act, which he saw as the first steps towards independence. He felt it important that Irish nationalists should support the king at this time, and gave his backing to the war effort. He believed that loyalty to the crown would be rewarded by the enactment of Home Rule. He mounted a campaign of publicity and oratory persuasion, travelling extensively to that end, giving speeches and attracting large crowds.

St Patrick’s Day on 17 March 1915 saw Redmond deliver one of the greatest acclaimed speeches of the First World War at the Free Trade Hall, Manchester, England:

Mr Chairman: If there is one thing more than another which I most value about this meeting it is its character. I have often, in the octave of St Patrick, had to speak in Manchester, but I have on these occasions addressed myself only to the Irish people of Manchester, I am proud to know that the present meeting is one not of Irishmen alone; but of Englishmen as well-[cheers]-firmly united in a common purpose. [Cheers.] I am proud to think it is a meeting of the representatives of every political party which existed in this country before the war, and the mere assembling of such a meeting in this great English centre is a proof of the profound and ineradicable change which has come over the Irish question.

When this war is over, we will all of us, of all previous parties, go back to the consideration of political questions in a new political world. [Cheers.] Ireland has been admitted to the democracy of England, upon equal terms, to her proper place in an Empire in the building of which she had as much to do as England herself [cheers] and she has taken that place with perfect and absolute good faith and loyalty. In ordinary circumstances this St Patrick’s Day of 1915 would have been for us a day of triumph, of universal congratulation and jubilation. But alas! For Ireland, the mother of sorrows, we are met today in a moment of suffering and deep tragedy. The moment for our jubilation is postponed. The shadow of war – ay, the shadow of death – hangs heavily over our people and our country, and our first and most immediate duty at this moment is not to give expression to triumph over our political successes, not to take part in jubilation or congratulation, but to do, every man and woman of us, what we can to see that Ireland bears her right and honourable part in the duty that is cast upon us.

[Cheers.]

From the day of the declaration of war to this moment I have not made one single controversial political speech, and I have spoken in every province in Ireland to the greatest and most united and most enthusiastic meetings that I ever faced in the whole of my political experience. My one theme has been to impress upon Ireland the duty of taking a part today worthy of her history and traditions. The one political hope I have ventured to express, and I express it again here with all the fervour of my soul, is that when the war is over the common dangers which all Irishmen of all creeds and all parties have faced together, the commingling of their blood upon the battlefield and their death side by side like brothers in a foreign land, may have the effect of utterly and completely and forever obliterating the bitterness and divisions and hatreds of the past, so that the new Constitution we have won may be inaugurated in a country pacified by sacrifices and amongst a people united by the memory of common suffering.

[Cheers.]

This is the first speech I have had the opportunity of making in Great Britain since the outbreak of the war, and I will confine myself to considering what the Irish race has done since the declaration of war. I am proud to make the boast that every section of Ireland has bravely and nobly done its duty. [Cheers.] I wish to draw no invidious distinction between one section of my countrymen and another. You will remember the circumstances of Ireland are peculiar. For more than half a century the flower of her manhood has been fleeing from her shores to distant lands. No part of Ireland has suffered more than another. The emigration from Ulster has been, if anything, greater than the emigration from the other provinces. In the last sixty years over 4 millions of people have emigrated from Ireland. Since the year 1900 over a half a million have emigrated, and two-thirds of the people who have gone have been young men of military age. I will not dwell on the sad political causes which ended in this emigration, but every man today must deplore the fact that for these reasons Ireland is not able to make a contribution in men towards this war such as she would have been able to make, if political and social and economic conditions had allowed her population even to remain stationary. Happily, for all of us, the drain of emigration has now been arrested. Last year, 1914, was the first year since the great famine when the population of Ireland actually increased. [Cheers.] The emigration for last year was 50 per cent, less than it was the year before. [Cheers.] It must also be remembered that Ireland is purely an agricultural country, and at present there is a great dearth of agricultural labour in many parts. There are few great centres of population after Dublin and Belfast, and yet in spite of these facts Ireland’s contribution to the army has been of a truly remarkable kind. [Cheers.] The Irish Government have given me some figures which they have laboriously collected from every parish in Ireland with reference to enlistments. These figures show that up to February 15 there were Irishmen from Ireland with the Colours to the number of 99,704. [Cheers.] Recruiting is going on at the present moment at the rate of about 4,000 a month. From December 15 to January 15 there were 3,858 recruits; from January 15 to February 15 there were 4,601 recruits. It has been stated that at the Grafton Street recruiting office in Dublin they are now getting over five times as many recruits as they got in August and September, and that the men are still coming in from all parts of the city and county of Dublin. There are so-called Unionists, so-called Nationalists, and – it is interesting to note – so-called Sin Feiners. [Laughter.] All young men now seem to be imbued with a new idea of their duties and responsibilities. There were with the Colours on February 15, 20,210 men who had actually enrolled and disciplined and drilled members of the Irish National Volunteers [cheers] and there were 22,970 Ulster Volunteers with the Colours.

The volunteers presented one of the most extraordinary spectacles ever seen in the history of our country. There are today in Ireland two large bodies of volunteers. One is called the Ulster Volunteers. They are partially armed and partially drilled, but they are all filled with the true military sentiment and spirit. Fifty thousand of them have joined the army, and of the rest many are not of military age, are not physically fit, or are prevented from joining the army by just the same reasons as prevented thousands of men in this country. But these men are quite capable of home defence. On August 3 in the House of Commons I told the Government that, for the first time in the history of the relations between England and Ireland, Ireland could be left safely to the defence of her own sons, and I appeal to the Government to allow the Irish to undertake that duty. At the same time, I made an appeal to the Ulster Volunteers to join hands with the National Volunteers in this work. I wish to make no complaint, but I think it right to say that I have received no response to either appeal. The Prime Minister on August 10 said the Government were seriously considering how the volunteers could be utilised, but that Lord Kitchener’s first duty was to raise his New Army. Subject to that, Mr Asquith said, and concurrent with it, he will do everything in his power to arrange for the full equipment and organisation of the Irish volunteers. Up to this time nothing has been done. Early in the war the Irish volunteers made an offer whereby 20,000 men could have been made available for home defence, so that not a single regular soldier need to be detained from the front for that purpose. The offer has not been accepted. I have some reason to think that in military circles in Ireland there is a strong feeling that from a purely military point of view, enlistment for home defence should be permitted; 20,000 men of Kitchener’s Army, who are supposed to be drilling and training for the front, are being wasted, by being engaged in defending various points on the coast, railways, bridges and waterworks. The whole of these men could be set free, if Irishmen were allowed to take their places.

I have told you that Ireland has sent from Irish soil over 100,000 men to the Colours. What about the Irish race in Great Britain and throughout the world? Some figures were recently published which showed that 115,000 recruits of Irish birth or descent had gone from Great Britain since the beginning of the war, and after making careful enquiries I am convinced that these figures err on the side of modesty. I have been told by responsible men in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, that an enormous proportion of the contingents sent by those countries to the army was made up of Irishmen. It is no exaggeration to say that at this moment the Irish race can number with the Colours at least a quarter of a million sons.