Table of Contents

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter ONE - Chickens 101

Physiology

Digestive Tract

Bones to Feathers

Sexual Characteristics

Behavior

Pecking Order

Mating

Tidying Themselves Up

Chicken IQ

Chicken Classifications

Chapter TWO - Which Chickens Are Best for You?

Chickens for Eggs or Meat

Avian Egg Machines

Meat Chickens

Dual-Purpose Chickens

Chickens as Pets

Big Bird or Chicken Little?

The Little Guys

The Big Guys

How Many Chickens?

Chapter THREE - City Chicks

Reasons to Raise City Chickens

First Things First: Check Those Statutes

Choosing a Breed

A Home for Your City Chicks

Keep it Clean

Keeping City Chickens is a Privilege

Chapter FOUR - Bring Back Those Old-Time Chickens

Heritage Chickens

Endangered Breeds

Buying Heritage Chickens

Chapter FIVE - Chicken Shack or Coop de Ville?

Your Coop: Basic Requirements

Access

Lighting and Ventilation

Insulation

Flooring

Your Coop: Basic Furnishings

Roosts and Nesting Boxes

Nesting Boxes

Feeders and Waterers

Outdoor Runs: Sunshine and Fresh Air

Fencing Them In

The Location

Building a Cheaper Chicken Coop

Owls and Weasels and ’Possums, Oh My!

Measures for Keeping the Varmints Out

Trapping Intruders

Determining Who Done It

Catching the Suspect

Chapter SIX - Chow for Your Hobby Farm Fowl

Commercial Feeds

Common Ingredients and Additives

Maintaining Nutritional Value and Freshness

The Supplement Approach

Grit and Oyster Shells

Scratch

Greens and Insects

Good Home Cookin’

Chicken Tractors, Pastured Poultry, and Free-Range Chickens... What Does It All Mean?

Chapter SEVEN - Chicks, with or without a Hen

Hatchery Chicks

Incubator Chicks

Choosing and Maintaining Your Incubator

Manipulating the Eggs

Incubating Timetable: Preparation to Pipping

Chicks the Old-Fashioned Way

The Hen

The New Chicks

Hatching Eggs 101

When You Don’t Want Chicks

Brooding Peeps

The Brooder

The Furnishings

Putting It All Together

Chapter EIGHT - Chickens as Patients

Maladies: Parasites and Diseases

Parasites, Lice, and Mites

Communicable Poultry Diseases: The Big, Scary Ones

Picking and Cannibalism

Chapter NINE - Farm Fresh Eggs and Finger Lickin’ Chicken

Getting the Best Eggs

The Right Hen for the Job

Egg-Laying Timetable

Who’s Been Eating My Eggs?

Tasty Chicken

Super or Dual-Purpose Birds

Broiler’s Timetable and Requirements

Making Meat Down on the Farm

Chapter TEN - Bucks for Clucks

Sell Fresh Eggs

Eggs for Direct Sales

Pricing Eggs

Marketing Eggs

Sell Hatching Eggs

Sell Live Chickens

Sell Feathers

Bang Your Own Gong

Your Chicken-Biz Website

It’s in the Cards

Publicity Doesn’t Have to Break the Bank

Chapter ELEVEN - Fun with Chickens

Keep a House Chicken

Enjoy Egg-Related Games

Show Your Chickens

Appendix I: Chicken Stories

Appendix II: Pick of the Really Cool Chicks

Appendix III: Layers at a Glance

Glossary

Resources

Photo Credits

Index

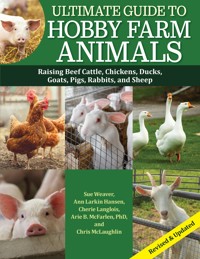

about the AUTHOR

Copyright Page

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to the wonderful folks at the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy for saving our heritage fowl and to David Puthoff for introducing me to Buckeye chickens.

INTRODUCTION

Why Chickens?

Seventy years ago, throughout the countryside and in cities large and small, backyard chicken coops were the norm. Chickens furnished table meat and eggs; most everyone kept at least a few hens. Years passed and attitudes shifted; small-scale chicken keeping became gauche. By the end of the twentieth century, while agri-biz egg and meat producers, immigrants, rustics, and aging hippies were keeping chickens, cultivated urban and suburbanites were not!

The times they are a-changin’ once again. As our world becomes increasingly frenetic, violent, and stressful, a burgeoning number of Americans are seeking a quieter existence. “We’ll move to the country,” some decide. “We’ll live on a small farm and commute or work from home; we’ll garden . . . we’ll have chickens!”

Nowadays, from Minneapolis to New Orleans, from Los Angeles to New York City and all points in-between, throngs of city dwellers and suburbanites raise and praise the chicken. A few miles farther out, more hobby farmers are apt to raise chickens than any other farmyard bird or beast. Hens are the critter du jour.

Why keep chickens? For their eggs, of course, and (for those who eat them) their healthier-than-red-meat flesh, whether strictly for your own table or for profit, as well. Chickens are easy to care for, and you needn’t break the bank to buy, house, and feed them. You may also wish, like many hobby farmers, to keep livestock for fun and relaxation. Surprisingly, chickens make unique, affectionate pets. They offer a link to gentler times; they’re good for the soul. It’s relaxing (and fascinating) to hunker down and observe them.

This book is meant to educate and entertain rookie and chicken maven alike. Are you with me? Then let’s talk chickens!

Chapter ONE

Chickens 101

Domestic chickens belong to the Phasianidae family, as do quail, grouse, partridges, pheasants, turkeys, snowcocks, spurfowl, monals, peafowl, and jungle fowl. Domestic chickens are descendants of the Southeast Asian Red Jungle Fowl (Gallus gallus, also called Gallus bankiva), which emerged as a species roughly 8,000 years ago. Today Red Jungle Fowl have disappeared from most parts of Southeast Asia and the Philippines, but a genetically pure population still exists in measured numbers in the dense jungles of northeastern India. In Latin, gallus means “comb,” and that is how chickens differ from their Phasianidae cousins. While chickens vary widely in shape and size, all have traits in common, including general physiology, behavior, and level of intelligence.

Physiology

Chickens see in color; their visual acuity is about the same as a human’s. While they don’t have external ears, they do have external auditory meatuses (ear canals) and hear quite well. Their frequency range corresponds to ours. Their smell is poorly developed, and they don’t taste sweets. They do, however, easily detect salt in their diets. Other important physiological characteristics to be aware of concern the digestive tract, internal and external structure (bones, muscles, skin, feathers), and sexual characteristics.

Digestive Tract

Chickens have no teeth. Instead, whole food moves down the esophagus and into the crop, a highly expandable storage compartment that allows a chicken to pack away considerable amounts of food at a time. When packed, it’s externally visible as a bulge at the base of the neck. Unchewed food trickles from the crop into the bird’s proventriculus (the “true stomach”), then to the ventriculous (another stomach, more commonly called the gizzard) to be macerated and mixed with gastric juice from the proventriculus. The food finally passes to the small intestine, where nutrients are absorbed, and then to the large intestine where water is extracted. From there it moves to the cloaca—the chamber inside the chicken’s vent (where its digestive, excretory, and reproductive tracts meet via the fecal chamber)—and finally out the vent. Food processing time for a healthy chicken is roughly three to four hours. Urine (the white component of chicken droppings) also exits the cloaca, but via the urogenital chamber.

Chickens at a GlanceKingdom:AnimaliaPhylum:ChordataClass:AvesOrder:GalliformesFamily:PhasianidaeGenus:GallusSpecies:Gallus domesticus

Bones to Feathers

While chickens have largely lost the ability to fly, some of their bones are hollow (pneumatic) and contain air sacs. Smaller fowl can fly into trees and over fences; when harried, heavy breeds try but usually aren’t able to get airborne. Chicken muscles are composed of lightcolor (white meat) and red (dark meat) fibers. Light muscle occurs mainly in the breast; dark muscle occurs in the chicken’s legs, thighs, back, and neck. Wings contain both light and dark fibers.

Skin pigmentation varies by breed (it can be yellow, white, or black). Its exact hue is influenced by what an individual bird eats and sometimes by whether a hen is laying eggs. When a yellow-skinned hen begins laying eggs, skin on various body parts bleaches lighter in a given order (vent, eye ring, ear lobe, beak, soles of feet, shanks). When she stops, color returns in the exact reverse order.

Domestication and Cockfighting

Before chickens, there was the Red Jungle Fowl (Gallus gallus), a flashy, chickenlike bird native to the forests and thickets of Southeast Asia. As a species, it emerged between 6000 and 5000 BC. By 4000 BC, Gallus gallus was domesticated—not for food but for cockfighting. By 3200 BC, high-caste Indian aristocrats were fighting cocks that resemble today’s Aseel chickens. Chickens—and cockfighting—spread in the following centuries as traders carried domesticated birds, or chickens, farther and farther throughout the ancient world.

When Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III embarked on his 1464 BC Asiatic campaign, he was presented with fighting stock as tribute. The first known depiction of domestic fowl—a fighting cock—is etched on a pottery shard of that period. Cockfighting became the rage in Athens around 600 BC and was an event at early Olympic games. Greek cockfighters passed the baton to ancient Rome. An avid cocker, Julius Caesar was pleased to find the sport already established in Britain when his army invaded the island in 55 and 54 BC.

British cockfighting peaked in popularity during the seventeenth century AD. Every British town boasted a cockpit. Gentlemen breeders held tournaments, often in conjunction with horse race meets. Cockfights were held in manor house drawing rooms, schools, and even in churches. In 1792, the First French Republic took the fighting cock as it emblem; the bird also figured in the design of countless family crests and military standards in France. On the other side of the Atlantic, as well, gentlemen—including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Andrew Jackson—raised and fought gamecocks; Benjamin Franklin was a noted referee.

Cockfighting remained a favored British pastime until 1849, when Queen Victoria banned it by royal decree. The sport moved underground, and the average gentleman abandoned his fighting fowl in favor of showing and creating new breeds of exhibition chickens. The movement to ban cockfighting met greater resistance in the United States. While a few progressive states outlawed it as early as 1836, most did not. When asked to support a ban, President Abraham Lincoln is said to have replied, “When two men can enter a ring and beat each other senseless, far be it for me to deny gamecocks the same privilege.”

By the end of the twentieth century, the majority of American states had made the practice illegal. There were a few stubborn holdouts. According to the Humane Society of the United States, cockfighting is now illegal in every state and the District of Columbia, and any animal fighting activity that affects interstate commerce is a felony under the federal Animal Welfare Act. Thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia have made cockfighting a felony offense. Thirty-four states and the District of Columbia prohibit the possession of cocks for fighting. And forty-one states and the District of Columbia prohibit being a spectator at cockfights.

This palm-size Silkie newborn will soon lose his fluffy down. Chicks begin developing feathers within a few days of birth.

Day-old chicks are clothed in fluffy, soft down. They begin growing true feathers within days and are fully feathered in four to six weeks. All genus Gallus birds, including wild jungle fowl, molt (shed their feathers and grow new ones) annually. Chickens molt from midsummer through early autumn, usually a few feathers at a time in a set sequence—head, neck, body, wings, tail—over a twelve- to sixteen-week period. Molting chickens are stressed and can be skittish, moody, and irritable. Molting hens will lay fewer eggs or stop laying altogether.

Sexual Characteristics

Growing chicks generate secondary sexual characteristics—including combs and wattles—between three and eight weeks of age, depending on their breed.

All birds in genus Gallus—chickens and jungle fowl—are crowned by fleshy combs and all, except the Silkie, sport a set of dangly wattles under their chins; other Phasianidae do not. Cocks develop larger and brighter-colored combs and wattles than their sisters. At about the same age, cockerels (young male chickens) begin crowing (pathetically at first) and sprout sickle-shaped tail feathers and pointed saddle and back feathers.

Pullets (young female chickens) reach sexual maturity and commence laying eggs at around twenty-four weeks of age. Although female embryos have two ovaries, the right ovary invariably atrophies and only the left matures. A grown hen’s reproductive tract consists of a single ovary and a 2-foot oviduct or egg passageway. Her ovary houses a clump of immature yokes waiting to become eggs. As each matures—about an hour after she lays her previous production—it’s released into her oviduct. During the next twenty-five hours, roughly, the egg inches along the oviduct, where it may be fertilized, enveloped by egg white (albumen), sheathed in a membrane, and sealed in a shell. Because each egg is laid a bit later each day and because hens don’t care to lay in the evening hours, the hen eventually skips a day and begins a new cycle the following morning. All the eggs laid in a single cycle are considered a clutch.

An angry hen flares her neck hackles to show she’s furious. Chickens typically keep to their flocks’ pecking orders, which means little infighting, but changes in routine such as relocation or flock additions can result in distressed birds.

Behavior

Chickens are easily stressed; stress seriously lowers disease resistance and stressed chickens don’t thrive. Panic, rough handling, abrupt changes in routine or flock social order, crowding, extreme heat (especially combined with high humidity), and bitter cold can stress chickens of all ages. Labored breathing, diarrhea, and bizarre behavior are the hallmarks of stressed fowl. To keep stress levels low, it is important that you understand chicken behavior.

Pecking Order

In 1921, while studying the social interactions of chickens, Norwegian naturalist Thorlief Schjelderup-Ebbe coined the phrase “pecking order,” now used to describe the social hierarchies of hundreds of species, including humans.

In any flock of chickens, there are birds who peck at other flock members and birds who submit to other flock members. This order creates a hierarchical chain in which each chicken has a place. The rank of the chicken is dependant upon whom it pecks at and whom it submits to. It ranks lower than those it submits to and higher than those whom it pecks at.

A flock of chicks generally has their pecking order up and running by the time they’re five to seven weeks old. Pullets and cockerels maintain separate pecking orders within the same flock, as do hens and adult roosters. Hens automatically accept higher-ranking roosters as superiors, but dominant hens give low-ranking cocks and uppity young cockerels a very hard time.

This handsome light Brahma trio explores the outer fence line of their Missouri home on the farm of Vic and Alita Griggs.

Name that Comb

What Is a Comb?

The fleshy protuberance atop a chicken’s skull is called its comb. Roosters’ combs are larger than those of same-breed hens. The American Poultry Association recognizes eight basic types:

1. Buttercup: Cup-shaped with evenly spaced points surrounding the rim.

2. Cushion: Low, compact, and smooth, with no spikes.

3. Pea: Medium-low with three lengthwise ridges. The center ridge is slightly higher than the ones that flank it.

4. Rose: Solid, broad, nearly flat on top, low, fleshy, and ending in a spike. The top of the comb is dotted with small protuberances.

5. Single: Thin and fleshy, with four or five points; it extends from the beak to the full length of the head.

6. Strawberry: Compact and egg-shaped, with the larger part toward the front of the skull and the rear part no farther than its midpoint.

7. V-shaped: Two hornlike sections connected at their base.

8. Walnut: Resembles half of a walnut.

Did You Know?

• The genus name for chickenlike fowl is Gallus, which means “comb.”

• The single comb is by far the most common type of domestic chicken comb. Its major drawback is that the points tend to freeze off in sub-zero temperatures. This doesn’t affect the wearer’s health, but it looks unsightly. Insulating a rooster’s comb with a layer of petroleum jelly during extremely cold weather usually prevents freezing.

• The large single combs of certain breeds of hen flop over in a jaunty manner instead of standing up like those of roosters.

• To qualify them for the show ring, owners of game breeds cut off their roosters’ combs and wattles in a process called dubbing. As game breeds were originally used for cockfighting, combs and wattles were snipped off so that an opponent couldn’t grab them during a fight.

• Chickens recognize some colors and are attracted to red combs. However, not all chickens have red combs. Silkies, Sumatras, and several color varieties of game fowl have purple combs, and Sebrights’ combs are deep reddish-purple.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

In a closed flock with an established pecking order, there is very little infighting. Each chicken knows his or her place, and except among some roosters, there is surprisingly little jockeying for position. Dominant chickens signal their superiority by raising their heads and tails and glaring at subordinates, who submit by crouching, tilting their heads to one side, and gazing away—or beating a hasty retreat.

The addition of a single newcomer or removal of a high-ranking cock or hen upsets the hierarchy and a great deal of mayhem erupts until a new pecking order evolves. Because brawls are invariably stressful, it’s unwise to move birds from coop to coop.

Low-ranking chickens are shushed away from feed and water by bossier birds, and they rarely grow or lay as well as the rest. Indeed, low-ranking individuals sometimes starve. If pecked by their betters until they bleed, they may be cannibalized by the rest of the flock. It’s important to provide enough floor space, feeders, and waterers so that underlings can avoid the kingpins and survive.

Mating

Like adult roosters, cockerels soon begin strutting, ruffling feathers, and peck-ing

This red hen displays a nearly denuded back, an injury received from a rooster’s sharp, spurred feet during breeding.

the earth to draw the eyes of nearby hens. This behavior is called displaying. Chicken mating behavior is direct and to the point. The rooster chases the hen or pullet; she crouches when the rooster mounts; insemination occurs. Cocks tread with their sharp toenails and sometimes rake hens with their spurs while mating, occasionally to the point of shredding the poor biddies’ backs.

Tidying Themselves Up

When their surroundings permit, chickens are tidy birds. They preen by distributing oil (from a gland located just in front of their tails) over and between their feathers. They also dust bathe. After scratching a shallow depression in suitable earth, they lie in it and kick loose dirt over their bodies, using their feet. A shake of the feathers after dust bathing sets things right.

Chicken IQ

When they founded their show-biz animal-training business in 1943, operant conditioning (clicker training) pioneers Marian and Keller Breland began by training chickens. Among the couple’s first graduates were a chicken who pecked out a tune on a toy piano, another who tap danced wearing a costume and shoes, and a third who laid wooden eggs to order (any number up to six) from a special nesting box. All were barnyard chickens rescued from a neighbor’s stew pot.

With her second husband, Bob Bailey, Marian Breland-Bailey used chickens to teach animal-training courses at their Animal Behavior Enterprises in Hot Springs, Arkansas. The couple chose chickens because the birds learn quickly, energetically perform for food, and move at lightning speed. They can easily learn new routines when trainees make mistakes and teach the wrong protocols. Budding trainers honed their reaction times to match those of the Baileys’ chickens.

Biological Makeup

Temperature: 103–103.5 degrees Fahrenheit

Pulse:

Roosters:

240–285 beats per minute

Hens:

310–355 beats per minute

Respiration:

Roosters:

15–20 breaths per minute

Hens:

20–35 breaths per minute

Chromosome count: 78

Blood volume:

Roughly 6 percent of body weight

Adult body weight:

1–10 pounds

Natural life span:

10–15 years (pet chickens

have lived for more

than 20)

A close kin of the chicken, this Royal Palm turkey is a good choice for small farms; the breed is good for meat production for a family and for pest control on the farm.

When asked by Animal Action (an Ottawa-based animal rights group) whether he considered chickens and turkeys dumb animals, Ian Duncan, professor of poultry ethnology at the University of Guelph, replied,

Not at all.… Turkeys, for example, …possess marked intelligence. This is revealed by such behavior indices as their complex social relationships, and their many different methods of communicating with each other, both visual and vocal. Chickens, as well, are far more intelligent than generally regarded, and possess underestimated cognitive complexity.

Chickens are as intelligent as some primates, says Chris Evans, animal behaviorist and professor at Macquarie University in Australia. Chickens understand that recently concealed objects still exist, he explains—a concept that even human toddlers can’t grasp. Chickens have good memories. “They recognize more than one hundred other chickens and remember them,” says Dr. Joy Mench, director of the University of California-Davis Center for Animal Welfare.

Dumb clucks? No, indeed!

Chicken Classifications

Early on, the American Poultry Association (APA) devised a system for classifying chickens by breed, variety, class, and sometimes strain. A breed is a group of birds sharing common physical features such as shape, skin color, number of toes, feathered or non-feathered shanks, and ancestry. A variety is a group within a breed that shares minor differences, such as color, comb type, the presence of a feather beard or muff, and so on. A class is a collection of breeds that originates in the same geographic region.

The APA currently recognizes twelve classes: (Large Breed) American, Asiatic, English, Mediterranean, Continental, All Other Standard Breeds; (Bantam) Modern Game, Game, Single Comb Clean Legged, Rose Comb Clean Legged, All Other Clean Legged, and Feather Legged. A strain, when present, is a group within a variety that has been developed by a breeder or organization for a specific purpose, such as improved rapid weight gain and prolific egg production. Chickens may also be classified as light or heavy breeds or as layers, meat, dual-purpose, or ornamental fowl.

Farmer Vic Griggs confines this flock of young light Brahmas to a grower coop. Brahmas are among the few breeds originally recognized in 1874 by the American Poultry Association.

A Matter of Breeding

Some of today’s purebred fowl (chickens whose parents are of the same breed), such as the gamecock breeds, trace their roots to the distant mists of antiquity.

Egypt’s elegant Fayoumi dates to before the birth of Christ. Stubbylegged, five-toed Dorkings came to Britain with the Romans. Squirrel-tailed Japanese Chabo bantams, a miniature chicken weighing between one and three pounds, emerged in the seventh century AD. Dutch Barnevelders were developed in the 1200s, about the time Venetian merchant Marco Polo wrote of the “fur covered hens” (Silkies) of Cathay. Another Dutch chicken, the deceptively named Hamburg, has existed since the late 1600s and is likely far older than that. The crested fancy fowl we call the Polish was developed even earlier, and France’s v-combed La Fletche dates to 1660 AD. Naked Necks, also called Turkens (possibly the weirdest-looking chicken of them all), originated in Transylvania before the 1700s. The first all-American fowl, the Dominique, is an early nineteenth-century New England utility fowl.

However, most breeds emerged between 1850 and 1925. Although Queen Victoria’s cockfighting ban had already spurred interest in exhibiting chickens, the arrival of the first Asiatic breeds set Britain afire. When Cochins were exhibited at the Birmingham poultry show in 1850, author Lewis Wright gushed, “Every visitor went home to tell of these wonderful fowls, which were big as ostriches and roared like lions, while as gentle as lambs; which could be kept anywhere, even in a garret, and took to petting like tame cats.” In 1865, the Poultry Club of Great Britain produced the inaugural edition of its comprehensive Standard of Excellence.

America’s first major poultry exposition was held on November 14, 1849. More than 2,000 birds were shown by 219 exhibitors, and more than 10,000 spectators attended. An American Standard of Excellence followed in 1874.

A Dominique pullet appreciates her tasty, new pasture. This first all-American poultry breed first appeared in the 1800s, a time of increasing interest in improving and refining poultry.

Centuries of fine-tuning breeding practices have resulted in beautifully colored birds, such as this rooster found nibbling in the grass.

When the APA published its first Standard of Perfection in 1874, the only chickens recognized were Barred Plymouth Rocks, light and dark Brahmas, all of the Cochins and Dorkings, a quartet of Single-Comb Leghorns (dark brown, light brown, white, and black), Spanish, Blue Andalusians, all of the Hamburgs, four varieties of Polish (white crested black, nonbearded golden, nonbearded silver, and nonbearded white), Mottled Houdans, Crevecoeurs, La Fleches, all of the modern games, Sultans, Frizzles, and Japanese bantams. In the volume’s latest edition, 113 breeds and more than 350 combinations of breeds and varieties are described.

Bantams are one-fifth to one-quarter the size of regular chickens. They come in sized-down versions of most large fowl breeds, although they aren’t scale miniatures: their heads, wings, tails, and feather sizes are disproportionally larger than those of their full-size brethren. A few bantam breeds have no full-size counterparts. Besides being cute, bantams can be shown, they make charming pets, and their eggs and bodies—small as they are—make mighty fine eating. The American Poultry Association issues a standard for bantams, as does the American Bantam Association. (These standards don’t always agree.)

Chapter TWO

Which Chickens Are Best for You?

All chickens aren’t created equal. It’s important to pick the ones who will meet your needs. There are countless varieties and hundreds of breeds from which to choose. With the passage of time, humans have designed chickens to fulfill every niche: cold-hardy chickens, heat-resistant chickens, chickens that don’t mind being penned up. We haven’t designed the perfect chicken—yet! All breeds have certain failings. Furthermore, a breed that would be a bad choice for one chicken keeper (such as hens meant to be confined who can fly out of enclosures) would be perfect for another (as free-ranging chickens, those flying hens would be able to evade dogs).

Before you can settle on the kind of chickens to buy, you need to determine what purpose they’ll serve and what environment they’ll live in. Do you want them for their eggs? Sunday dinner? Feathery companionship? Will they spend most of their time inside or out? Will they have to contend with sweltering summer days or frigid winter nights? All of these factors make a difference in your choice of breed.

Next you must decide whether you want day-old chicks or full-grown birds as well as how many of them to get. What advantages are there to buying a pullet rather than a chick? Is it better to start with a small flock? If you haven’t already done so, you should also find out what zoning laws may apply to your keeping chickens and how they affect your decision. Do you need quieter birds?

Ask yourself the following types of questions:

• Will your birds be sequestered in a chicken house, or do you favor free-range hens? Certain breeds don’t like being confined while others know nothing but. A cramped coop of ornery Sumatras is a disaster waiting to happen, and findyour-own-feed Cochins might starve.

• How much room do you have to devote to chickens? A few banties can thrive in a doghouse. A dozen 10-pound Jersey Giants? They’ll need a heap more space.

• Are your neighbors close by? Squawking, kinetic, freedom-craving, fence-flying breeds likely won’t do. This is especially true if you live in the city or suburbs. We’ll talk more about city chickens in chapter 3.

• Are there toddlers in your family? Testy roosters of certain breeds can injure an unwary tot.

• Do winter temperatures plummet below zero where you live? Roos with huge single combs frostbite easily and some breeds simply won’t thrive in this type of weather.

• Are you in a region with hot temperatures? Fiery summer heat wilts heavy, soft-feathered breeds such as Cochins, Australorps, and Orpingtons, while other breeds take heat more in stride.

• Can you keep your top-knotted, feather-legged friends confined when the weather turns foul? Mud, slush, and fancy-feathered fowl usually don’t mix.

• Would you like to preserve a smidge of living history and raise old-fashioned or endangered breeds? We’ll discuss Heritage chickens in chapter 4.

• Finally, if your chicken is a pet, will you keep it outdoors with the rest of the chickens or as a household pet? A chicken in the house? Yes, indeed! Read about house chickens in chapter 11.

Though we can’t tell you exactly which breed to buy—describing all the possibilities is beyond the scope of this book—we can offer general advice and name birds that will meet certain criteria. (See “Which Breed?” in this chapter.) We also list other sources in the back of the book to help you make your decision.

Leghorns are great egg-layers, but you’ll need a covered enclosure if you want one because they’re among the flying breeds.

In a typical strutting fashion, this silver-laced Wyandotte rooster makes his dominance known, even on the outskirts of his pasture. As both egg layers and meat producers, dual-purpose breeds (such as the Wyandotte) are great additions to any hobby farm.

Chickens for Eggs or Meat

Birds with the greatest egg-laying capacity are not the same as those who plump up into the best candidates for the local chicken fry. Still different are the chickens that are the best choice for providing both eggs and meat.

Avian Egg Machines

If you want eggs—and a whole lot of them—Mediterranean breed chickens are just your thing. Small, squawky, and hyperactive, these birds mature quickly, and then everything they eat goes into laying eggs. Undisputed queens of the nesting box are white Leghorns and hybrid layers based on this breed. Other impressive Mediterranean-class layers are the Minorca, Ancona, Buttercup, Andalusian, and Spanish White Face.

Some chickens from other classes are laying machines, too. The Campine (Belgium), Fayoumi (Egypt), Lakenvelder (German), and Hamburg (Continental Europe) are popular examples. Like their Mediterranean sisters, they tend to be flighty, specialist hens.

Meat Chickens

Meat chickens (called broilers or fryers )—usually White Cornish and White Plymouth Rock hybrids—have broad, meaty breasts and white feathers, and they mature at lightning speed. Broilers are ready for the freezer in about seven weeks, and roasters (which are just larger broilers) are ready in just three more.

Be aware that because they’re hybrids, these birds don’t breed true—meaning their chicks won’t possess these stellar features. They also require careful handling; because of their abnormally wide breasts and rapid growth patterns, most become crippled as they mature.

Dual-Purpose Chickens

Dual-purpose breeds lay fewer eggs than superlayers and mature a heap slower than meat hybrids, but they’re ideal allaround hobby farm birds. They’re quieter, gentler, and friendlier than the specialists, and they’re hardy and self-reliant, to boot. They are broody, so hens will set and hatch their own replacements. Nearly all lay brown eggs and are meaty enough to eat, should you wish to do so.

With a few notable exceptions, dual-purpose birds hail from the English and American classes. There are scores of interesting breeds and varieties.

Chickens as Pets