Table of Contents

Dedication

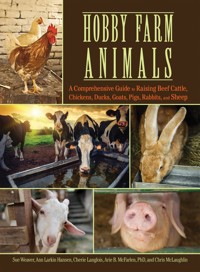

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE - Sheep from the Beginning

SHEEP AT A GLANCE

SHEEP IQ

FLOCKING INSTINCT AND SOCIAL STRUCTURE

STRESS AND FLIGHT ZONE

BREEDING TRAITS

SHEEP CLASSIFICATIONS

WOOL

SHAPE, SIZE, AND REGION

DAIRY AND MEAT

SCARCE AND ENDANGERED

CHAPTER TWO - Buying the Right Sheep for You

WHAT TO BUY

CHOOSING THE BREEDS

SELECTING THE SHEEP

EWE HAUL . . . AND THEN?

CHAPTER THREE - Housing, Feeding, and Guarding Your New Flock

LIE DOWN IN GREEN PASTURES

(DO) FENCE ME IN

SHELTERS

PENS AND STALLS

SHEEP FEEDING PRINCIPLES

HAY THERE!

ALL THE AMENITIES

GUARDING YOUR SHEEP

CHAPTER FOUR - Sheepish Behavior and Safe Handling

WHY THEY DO THAT THING THEY DO

FLOCKING

FLEEING

DO EWE READ ME?

READER POSITIONS

SHEEP SIGNS

HANDLING SHEEP

CATCH ME IF EWE CAN

SAFETY

CHAPTER FIVE - Health, Maladies, and Hooves

MAINTAINING A HEALTHY FLOCK

SHEEP AFFLICTIONS

YOU’RE CALLING THE SHOTS

PARASITES

FLIES, LICE, AND TICKS

WORMS

HOOVES

TRIMMING HOOVES

FOOT ROT!

SAFETY WITH NEW SHEEP

CHAPTER SIX - The Importance of Proper Breeding

CHOOSING BREEDING STOCK

BREEDING

THERE BE LAMBS!

PREPARING FOR THE LAMBS’ ARRIVAL

ARRIVAL

NEW LAMBS

TAILS

CHAPTER SEVEN - Fleece: Shearing, Selling, Spinning

THE FLEECE COMES OFF

TIME IT RIGHT

THE PROFESSIONAL SHEARER

WHEN THE SHEARER IS YOU

SHEEP CHIC

SELLING THE FLEECE

THE LINGO

HANDSPINNING

DROP-SPINDLE SPINNING

CHAPTER EIGHT - Mutton or Milk?

LAMB AND MUTTON PRODUCTION

MARKETS

THE RIGHT BREED

MILK: THE NUTRITIOUS STUFF

THE ADVANTAGES OF PRODUCING SHEEP’S MILK

HOUSEHOLD DAIRY SHEEP

DAIRY-SHEEP BREEDS

Acknowledgements

Appendix: A Glance at Sheep Afflictions

Glossary

Resources

Photo Credits

Index

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Copyright Page

This book is dedicated to Baasha (Brighton Ridge Farms #A-80), the matriarch of our flock and a really neat sheep…

…to Dick Harward and Barb Zebbs of Wind Fall Farm in Willow Springs, Missouri, for allowing us to photograph their beautiful Scottish Blackface sheep.

…and to Laurie, Cathy, Lyn, Lynn, Barbara, Marion, Kim, Dawn, Bernadette, Kris, Melissa, Connie, Kelly, Kathy, Liz, Lisa, Michelle, and all the other shepherds at the Hobby Farms Sheep E-mail discussion group. Thanks for your help, ladies!

INTRODUCTION

Why Sheep?

Sheep are to hobby farms as diamonds are to gold: they make a good thing better. Be they pets or profit makers, sheep should be part of every small-farm scene. They are inexpensive to buy and keep, easy to care for, and relatively long lived, making them great investments. Given predator-proof fencing, minimal housing, good feed, and a modicum of daily attention, sheep will thrive. New shepherds can learn to care for sheep in a relatively short period of time, which makes them attractive even to first-time farmers. Sheep make delightful pets; they’ll mow your yard, come when called, and with training, maybe even pull a cart.

Farmers looking to turn a profit in sheep can do so. Hand-tamed miniature lambs fetch respectable prices as pets. Clean fleeces from many breeds are wildly popular among handspinners. Niche-marketed lamb sells readily to ethnic and organic markets, and sheep’s milk cheese is popular with gourmets around the world. In addition, raising livestock qualifies landowners for lower agricultural land tax assessments in many locales.

You may have reservations; even I haven’t had sheep all my life. For more than fifty years I was blissfully content with husband, horses, and dogs. Then came hobby farms—then guineas, chickens, and an ox. I had always liked sheep, so why not give them a try? I was smitten, totally and thoroughly captivated by our first woolly pets. Now sheep are a part of me. I’ve been entrusted with the care of these beautiful creatures. I’m sure I’ve been blessed!

CHAPTER ONE

Sheep from the Beginning

In the beginning, there were majestic wild sheep called mouflons. Hunters stalked the wily sheep to dine on their tasty flesh and to craft cozy clothing from their hides. About 11,000 years ago—probably near Zawi Chemi Shanidar, in what is now northern Iraq—a hunter stopped fiddling with his spear point, kicked a log onto the fire, and said to a friend, “Wouldn’t it be smarter to snatch some lambs and raise them here by camp?”

So humans and sheep formed an alliance. People protected sheep from wolves, bears, and mountain lions; sheep reciprocated by developing wool. About 3500 BC, women puzzled out how to weave sheep’s woolly covering into fine, sturdy cloth that kept wearers toasty in the wintertime and cool under the blazing summer sun. Decked out in woolen garments, men said to one another, “We don’t have to stay here on the Mesopotamian plains where it’s always pretty warm; we could go out and conquer the world!”

Sheep were already out in the world. Domestic sheep had reached parts of Europe by 5000 BC, having been carried west by intrepid Neolithic farmers. (Sheep remains have been recovered from a Swiss New Stone Age dig circa 2000 BC.) Swedish farmers began raising northern short-tailed sheep between 4000 and 3000 BC. Between 1000 BC and AD 1, Persians, Greeks, and Romans labored to develop new and better sheep. The Romans brought their revamped woollies along (a walking food supply) when they conquered Europe and North Africa; by AD 50, the Romans had erected a wool-processing plant near Winchester, England.

Historically, the greatest sheep was the mighty Merino. Some researchers think it sprang from a genetic mutation some 3,000 years ago; others believe it was developed during the reign of Queen Claudia of Spain (AD 41–54). Whatever the case, income from the Spanish Merino wool trade transformed Spain into a world power and financed its New World voyages. Until the mid-eighteenth century, in fact, Spain so hoarded Merinos that it made smuggling sheep out of the country punishable by death.

When Columbus embarked on his second voyage, in 1493, he packed along big, meaty Spanish Churra sheep. He left some in Cuba and more in Santo Domingo. Their descendants trailed Cortez and his conquistadors as they pillaged their way across the New World.

This vintage European Easter card is filled with historical symbols of the season: children in traditional dress, pussy willow boughs, springtime flowers, and fluffy sheep.

Meanwhile, another wave of sheep arrived by way of the North American colonies. Fifteen years after settling Plymouth Colony, the Pilgrims purchased sheep from Dutch dealers on Manhattan Island. By 1643, there were 1,000 sheep in Massachusetts Bay Colony alone. Records show that Governor Winthrop, of the Connecticut colony, acquired a handsome flock of Southdown sheep in 1646. By 1664, an estimated 100,000 sheep called the thirteen colonies home.

Trafficking in sheep or wool was risky business. By 1698, Americans were peddling their wool abroad—much to the consternation of the British king William III. William ultimately outlawed the production of sheep and wool in the colonies. Miscreants caught engaging in the trade had their right hands amputated.

Yet intrepid shepherds continued raising sheep before, during, and after the American Revolution. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were inaugurated in suits crafted of pure American wool. Both presidents were, in fact, avid sheepmen. Washington raised English Leicesters at Mount Vernon; Jefferson bred English Leicester and Tunis sheep at Monticello.

During the nineteenth century, a slew of European breeds appeared on the American scene. Coveted Spanish Merinos (1808), Lincolns (1825), Cotswolds (1832), Shropshires (1855), and Hampshires (1885) arrived and flourished. In 1912, the first all-American breed, the Columbia, was developed.

Sheep in Myths

Back to the Dawn of time:

It stands to reason, considering humanity’s long association with sheep, that myth and religion embrace them, too. The Egyptian sun god, Amon-Ra, was depicted as either a ram-headed deity or a sun disc with ram’s horns. Other ramhorned deities include the Middle Eastern great goddess Ishtar; the Phoenician sun god Baal-Hamon; and Ea-Oannes, the Babylonian god of the deeps.

The Greek goddess of crossroads, Hecate, is associated with sheep—especially black ewe lambs. Pan was the god of sheep and flocks. A famous mythical sheep was the golden ram, Khrysomallos, a wooly son of Neptune and Theophane, conceived when they appeared in the forms of a ram and a ewe. Flying Khrysomallos carried the children Phrixos and Helle to Kolkhis, where Phrixos sacrificed Khrysomallos to the gods and hung his fleece in the holy grove of Ares. It became the object of Jason and the Argonauts’ quest for the golden fleece.

The Romans had Palas, the guardian of their flocks. On his feast day (the Parilia, April 21) sheepfolds were decked with greenery, and a wreath was placed on every entrance. Chuku, supreme deity of the Ibo in Nigeria, once sent a messenger sheep to tell humans that the dead should be placed on the earth and have ashes sprinkled over them; then, they would come back to life. But the sheep forgot the message and decided to wing it, directing instead that the dead should be buried in the ground.

Fairy lore is rife with sheepy connections. The Scots-Irish shape-shifting buachailleen play pranks on shepherds, such as spooking the sheep or smearing their fleeces with muck the night before shearing. Iron bells suspended from collars around sheep’s necks protect them from the buachailleen. According to Welsh fairy folk, sheep are the only creatures allowed to graze the grass growing in fairy rings. That, according to legend, is what makes Welsh mutton the best in the world.

America’s sheep population peaked in 1942, at a mind-boggling 56.2 million head. Today there are 6.35 million head, and that’s down a hefty 14 percent since 2001. The good news is that although large-scale commercial sheep operations are faltering, there is a burgeoning unmet market for specialty products such as handspinners’ fleece, gourmet sheep’s milk cheeses, and certified organic lamb—products raised on, and marketed from, today’s small farms.

Sheep come in many sizes, shapes, colors, and temperaments. They can be classified by type of fleece produced, appearance, or place of origin.

Consequently, they offer a wide variety of characteristics to breeders and consumers alike. However, supplies are not unlimited, and some breeds are considered endangered.

SHEEP AT A GLANCE

Domestic sheep (Ovis aries) belong to the Bovidae family, along with other hollowhorned, cloven-hoofed ruminants such as cattle, and to the Caprinae subfamily, in the company of their cousins, the goats. There are more than 1,000 breeds of domesticated sheep in the world today—more than three score of them in North America alone. While size, shape, type of fleece (or lack thereof), and disposition vary greatly, all domestic sheep have certain traits in common. We’ll discuss many of these items later. For now, here are sheep at a glance.

SHEEP IQ

The University of Illinois monograph “An Introduction to Sheep Behavior” ranks sheep IQ a smidge below that of the pig and on a level with cattle. Researchers at the Babraham Institute in Cambridge, England, trained twenty sheep to recognize pictures of other sheep faces. Electrodes measuring their brain activity proved that some remembered at least fifty of the faces for up to two years. “It’s a very sophisticated memory system,” explains Dr. Keith Kendrick. “They are showing similar abilities in many ways to humans.”

Packaged as tightly as canned sardines, these white-faced sheep are comforted by their close quarters. Sheep have a natural flocking tendency and stick together as means of protection.

Sheep also learn and respond to their names. Club lambs and exhibition sheep lead, stand tied, allow extensive grooming, and pose in the show ring. Pet sheep learn to pull carts; some even do tricks. Sheep, intelligently and quietly handled, are very trainable.

Sheep are not stupid; they are reactive. Their only means of survival is to band together for protection, then to run. Frightened, stressed sheep flee blindly, pack into corners, and get wedged behind gates. Quietly handled sheep generally do not.

FLOCKING INSTINCT AND SOCIAL STRUCTURE

Sheep are gregarious, meaning they crowd together for reassurance and protection. They have a strong inner compulsion to follow a leader. These traits compose their flocking instinct. In most cases, the leader is simply the first sheep that starts moving in a given direction; flock hierarchy rarely enters the picture.

White-faced (wool) sheep are more gregarious than are black-faced (meat) breeds. When stressed, huge flocks of Australian Merinos can pack so tightly that humans swept up in the crush are injured or killed. Weakly gregarious breeds include the Suffolk, Hampshire, Corriedale, Cheviot, Leicester, and Dorset. Because strongly gregarious breeds tend to move as a group instead of scattering, herding them is easier than mustering breeds that are not gregarious, especially when using a herding dog.

Biological Traits

Temperature: 102.5 degrees Farenheit

Pulse: 75 beats per minute

Respiration: 16 breaths per minute

Chromosome count: 54

Adult body weight: 65-475 pounds

Natural life span: 6-14 years (well-kept sheep have lived 20 years or more)

Sight: Although they have poor depth perception, sheep see in modified color and, unless wool on their faces obstructs their vision, they have a 270-to 320-degree visual field.

Smell: Sheep have a keen sense of smell. Rams determine which ewes are in standing heat by sniffing them; ewes identify new lambs by scent.

Hearing: Sheep are more sensitive to high-frequency sounds than we are; clanging gates and shrill whistles annoy and frighten them.

Teeth: Mature sheep have 32 teeth, including 4 pairs of lower incisors, but none in their upper front jaws; a hard dental pad replaces the absent upper incisors.

Advice from the Farm

Rams at a Glance

Our experts offer a few snapshots of rams, their behavior, and techniques for dealing with them.

The Crack of Heads for Dominance

“Rams start cracking heads as breeding season arrives—it’s their way of showing their dominance.

“This summer, one of our young rams took aim on me a couple different times in a week’s span. Each time, I responded with a swift kick. One time this fall, he was standing there looking at me from about ten feet away with a funny look in his eye. I kept my eye on him, and he walked up to me, placed his head on my thigh and pushed—he knew not to come at me from a distance and get up a head of steam.

“Rams tend to view us as part of the herd, too, and we have to keep our dominance in the flock to remain top dog. Otherwise, we are in trouble.”

—Lyn Brown

The Dangerous Turn on a Dime

“Never trust them. Your sweet ram that has never hurt you once can turn on a dime and run you down. Be smart; keep your eyes on him.”

—Laurie Andreacci

The Blaster Solution

“I have a bottle-raised ram that got a little aggressive. What we did was, we bought a set of water blasters. Every time he even suggested he was coming at us, he would get a blast in the face. It didn’t take him long to figure out he’d rather stay away. After a while, we didn’t need to carry the water blasters any more. About once a year, he starts acting rammy, and we have to have a refresher course.”

—Lyn Brown

The Husband Toss

“Some people have a tendency to think that because rams are relatively small (compared to stallions and bulls), they are just sweet little things, as lambs are portrayed in so many ways. But these are animals with animal instincts, and they will try to dominate you—and often do.

“I had a large Suffolk ram keep me in a hay feeder we put out in the middle of the barnyard instead of close to ‘people getaway places.’ I was up there for about a half hour before he lost interest.

“We had an older North Country Cheviot ram who was the tamest, sweetest ram you could ever imagine. One day, after having not been in that particular pasture for some time, we herded them into the barn, and he rammed me against the fence. Before I could get up and untangled, he got me again. Luckily he couldn’t get a good run at me, or he would have broken my hip.

“I’ve noticed that sometimes a good spray of water will stop them long enough to get away. I’ve even grabbed my husband (now ex) and put him in-between us to get away. It worked, too!”

—Connie Wheeler

The sheep leading the way along this road isn’t necessarily the queen bee of the flock. She’s just the first one to start walking.

While there usually is no flock leader, every flock of sheep does incorporate a pecking order, or social hierarchy. This is especially evident at feeding time, when high-ranking members eat first and those near the bottom eat last (if at all) . In large flocks, several hierarchies may exist simultaneously. The ewes maintain a pecking order among themselves ; rams maintain another; a third power play exists between the sexes. Jostling for position translates into head butting, shoving, and body slamming. Ewes are fairly subtle about it; rams indulge in all-out warfare.

Sheep want companionship, preferably that of other sheep. They’ll make do with a goat, a pony, or a donkey companion, but they won’t be as happy and might not thrive. They also prefer other sheep of the same breed. In mixed flocks, breed-specific subflocks are the rule. When they can, sheep form family groups within their flock or subflock. A family might include an old ewe and her daughters and granddaughters, along with all three generations’ suckling lambs.

Domestic versus Wild Sheep

• Most domestic sheep produce wool; wild sheep grow hair.

• Domestic sheep are generally shades of white or black; wild (and primitive domestic) sheep lean toward browns.

• Most domestic sheep have lop ears; wild sheep’s ears stand erect.

• Some domestic breeds are naturally hornless; wild sheep, even ewes, are horned.

• Many domestic sheep breeds have more tail vertebrae than do wild sheep.

• The domestic sheep’s brain is smaller than that of his ancient ancestors as well as that of today’s wild sheep.

A flock groups together to face a large, aggressive dog. A few steps closer, and the dog will trigger the sheep’s instinctive flight response.

STRESS AND FLIGHT ZONE

Because sheep are gregarious, separating them from other sheep stresses them. Harsh handling, loud noises, and the presence of predators (including dogs) also stresses them, as does lengthy confinement. Prolonged stress triggers cortisol production, and elevated cortisol levels significantly reduce immunity. Stressed sheep tend not to thrive. Symptoms include panting, restlessness, teeth grinding, and skittishness. Closely confined sheep, even those penned with their peers, gnaw wood and nosh on wool—their own or that of underling companions.

Sheep maintain personal security zones, or “space.” Anything scary invading an individual’s personal space generates flight. A sheep’s flight zone might be fifty yards or nothing at all; breed, gender, tameness, training, and the degree of threat enter each equation.

If something arouses a sheep’s suspicion, she will watch it closely. Her vigilance will alert others within the flock. If danger stays beyond the most timid observer’s flight zone, the flock stays put. When her security zone is breached, she will turn and flee, and her flockmates will run then, too. Alarmed sheep stampede first and ask questions later. Instinct assures them that she who tarries is the sheep most likely to be eaten.

BREEDING TRAITS

Rams become sexually active between five and eight months of age. One mature ram can service thirty to thirty-five ewes in a typical sixty-day breeding season. Ram semen can be collected and successfully frozen. Ewes reach puberty between six and eight months of age, but they generally shouldn’t be bred (depending on breed and maturity) until they’re eight to twelve months old. Most ewes come into heat seasonally from early fall through early winter. Some breeds, such as Dorsets, Dorpers, Katahdins, and St. Croix, come into heat year-round.

This newborn sticks close by mama’s side. Take time to observe the temperament of the parent sheep before purchasing a lamb. Jumpy moms produce spooked little ones.

A ewe’s heat lasts twenty-four to thirty-six hours. Unless she’s impregnated, she’ll cycle every fourteen to nineteen days throughout the breeding season. Ovulation occurs twenty-four to thirty hours after the cycle begins. A ewe may be bred by natural cover (that is by a ram) or, more rarely, by artificial insemination, using fresh or frozen semen.

Most ewes lamb 145 to 155 days after conception, producing from one to as many as seven lambs, depending on age and breed. Twins and triplets are common. Ewes have only two teats, but so-called good milkers successfully rear triplets without help. Lambs are precocial, meaning they stand, nurse, and frisk about soon after birth. Commercial ewes are often culled when they reach five or six years of age, but depending on her breed and how she’s been cared for, a ewe can often lamb until the age of twelve.

SHEEP CLASSIFICATIONS

Sheep can be classified by the types of wool or hair they grow, their shapes and sizes, and their regions of origin. Farmers also look at sheep in terms of dairy and meat production capabilities. Organizations such the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy think in terms of scarce and endangered breeds.

WOOL

You can judge sheep by their covers without a blush. Categories include fine and carpet wool, medium and long wool, and hair (instead of wool). British breeds, which have been exported to North America since colonial times, are categorized as either long-wool and luster or short-wool and down sheep. All are represented in North America today. Nearly every American breed incorporates British breed genetics.

A sheepish face looks out of a sea of wool. Length, texture, and luster of wool distinguish one breed of sheep from another.

Fine-wool sheep, such as Merino and Rambouillet (ram-boo-LAY), produce the soft, white wool used to make cushy, comfortable-next-to-the-skin garments. At the other end of the spectrum are the coarse-wool breeds, such as Scottish Blackface and Karakul, that produce the fleece used to stuff mattresses and to craft sturdy Scottish and Irish tweeds and rugs. In between are the medium- and long-wool sheep, whose fleeces are used mainly to make cozy outer garments and quality wool blankets.

Cheviots, Clun Forests, Dorsets, Finnsheep, Hampshires, Montadales, Oxfords, Polypays, Shropshires, Southdowns, Suffolks, Texels, and Tunises are medium-wool sheep. Long-wool and luster breeds, which produce long, lustrous, wavy, or ringleted fleeces of finer quality than those of their hillbred brethren, include the Leicesters (LIS-ters) (Blueface Leicesters, Border Leicesters, and Leicester Longwools, Lincolns, Romneys, and Wensleydales). Other long-wool sheep are Coopworths, Cotswolds, and Perendales.

In Pullman, Washington, blackface ewes enjoy a crisp, autumn morning. The valley provides the perfect environmental conditions for the flock.

America’s favorites, Suffolks and Hampshires, belong to the short-wool and down group. Less common (and in some cases endangered) short-wool and down breeds include the Clun Forest, Dorset, Jacob, Shetland, Shropshire, and Southdown. Some primitive sheep breeds grow hair instead of wool; others grow short, self-shedding fleeces. Because shearing can cost more than commercial wool is worth, and because hair-sheep lamb carcasses are bestsellers at ethnic meat markets, hair sheep, such as the Barbados Blackbelly, Dorper, Katahdin, St. Croix, and Wiltshire Horn (an ancient British breed), are a wave of the future.

SHAPE, SIZE, AND REGION

Other classifications of sheep deal with shape, size, and region. For instance, sheep tails tell their own tales. Fattailed sheep, native to the arid regions of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, store body fat in their tails and rumps. This group includes Damara, Karakul, and Tunis sheep. Short-tailed breeds boast ancient Scandinavian roots, some via the sheep taken to Britain’s northern isles by intrepid Viking settlers. Most are small, medium-wool breeds with soft, colorful fleeces and naturally short tails. They include Finnsheep, Icelandics, and Shetlands.

Classified by their small stature are miniature sheep breeds such as Babydoll Southdown and Keyrrey-Shee, which measure 24 inches or smaller at their newly shorn shoulders. American Brecknock Hill Cheviots measure 23 inches or less. Two other wee breeds are the Shetland and Black Welsh Mountain. Although miniature sheep are usually marketed as pets, they also sport fleeces that are a handspinner’s delight.

My husband, John, carries Baabara, one of our Keyrrey-Shee miniature sheep. Minature sheep make the best of pets; a pair will be happy in a large backyard—and they’ll keep it mowed and gently fertilized, too.

Some breeds known by their regions are the mountain and hill sheep of Great Britain. These hardy, thrifty animals, generally medium size or smaller, adapted to life in Britain’s rugged hills and highlands. Mountain and hill breeds found in North America include Cheviots (American Brecknock Hill Cheviot, Border Cheviot, Keyrrey-Shee, North Country Cheviot), Black Welsh Mountain, and Scottish Blackface.

DAIRY AND MEAT

Farmers raise sheep not only for wool but also for dairy products and meat. The American dairy sheep of choice is the highproducing East Friesian Milk Sheep. An increasing crowd of American sheep owners are clambering aboard the sheep-dairying bandwagon. Rich, mild-tasting sheep’s milk is higher in protein, calcium, and fat—as well as vitamins A, D, and E—than is cow or goat milk, making it an ideal cheese-making medium. Many of the world’s great cheeses are made from ewe’s milk. These include Greek Feta, Kasseri, and Manouri; Spanish Iberico, Manchego, and Roncal; Sicilian Pepato and Ricotta Salata; and that perpetual French favorite, genuine Roquefort cheese.

Our ewe Angel is truly a rare breed; not only because she is a Wiltshire Horn crossbred, but also because she has horns (an unusual trait for ewes).

Medium- and long-wool breeds are sometimes called dual-purpose sheep because they are raised for meat as well as wool. During the twentieth century, breeders created additional dual-purpose varieties by crossing Merino or Rambouillet fine-wool sheep with medium- and long-wool sheep. These new breeds include the Corriedale, Cormo, Romeldale, and Targhee. The British long-wool and luster sheep are also bred for both meat and wool.

SCARCE AND ENDANGERED

Commercial breeders generally raise big, meaty breeds, such as the Suffolk and Hampshire; wool factories prefer the Merino and Rambouillet. Many producers crossbreed for added productivity. As a result, a great many of yesterday’s sheep breeds are becoming scarce and endangered.

The American Livestock Breeder’s Conservancy publishes a priority list of threatened breeds. Critically endangered sheep include the California Variegated Mutant/Romeldale, Gulf Coast Native, Hog Island, and Santa Cruz. Breeds considered rare are the Cotswold, (American) Jacob, (American) Karakul, Leicester Longwool, Navajo-Churro, St. Croix, Tunis, and Wiltshire Horn.