Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The outbreak of war in 1914 was greeted with euphoria by many in Europe, and it was widely believed that the conflict would be 'over by Christmas'. In the event, millions of men were destined to spend the first of four seasons away from their families and loved ones. Amid the shortages, tedium and dangers of life in the trenches, those at 'the sharp end' remained determined to celebrate Christmas as a time of comradeship and community, a time when war could be set aside, if only for a day. Unlike the famous Christmas truce of 1914, the Christmas experiences in other years of the war and on other fronts have received scant attention. Alan Wakefield has trawled the archives of the Imperial War Museum, National Archives and National Army Museum to provide a fascinating selection of first-hand accounts of the six wartime Christmases of the First World War.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 251

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Christmas

INTHE

TRENCHES

Christmas

INTHE

TRENCHES

ALAN WAKEFIELD

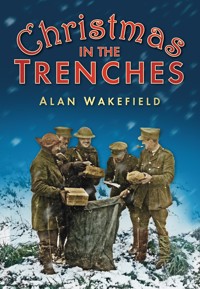

Front cover: Officers of the Royal Field Artillery with their Christmas mail bag, December 1917 (Q 8346, Imperial War Museum).

Back cover: Top to bottom, Christmas card produced by the 53rd Battalion, Australian Imperial Force, 1918. (Private Collection). Christmas card produced for the 56th (London) Division, 1917. (Private Collection).

First published in 2006

This edition published in 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

©Alan Wakefield, 2006, 2010, 2013

The right of Alan Wakefield to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5321 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1.

The First Christmas: 1914

2.

Christmas 1915

3.

Christmas 1916

4.

Christmas 1917

5.

Peace at Last! Christmas 1918

Postscript

Notes

Sources

Acknowledgements

I would like to take the opportunity to thank a number of people whose assistance made the research for and writing of this book a relatively straightforward task. Firstly, Anthony Richards of the Imperial War Museum’s Department of Documents, who not only kept up with my call for collections of letters and diaries, but also took on the task of proof-reading the first draft of my manuscript. I would also like to thank Nina Burls from the RAF Museum’s Department of Research and Information Services for helping me access the Roscoe collection. Staff of the National Archives must also be thanked for facilitating access to the battalion, brigade and divisional war diaries in their charge.

Access to the written material is only half the story and I acknowledge the permission given by copyright holders to reproduce material in this book, without which the project could not have been completed. Alongside the numerous individual copyright holders are the Trustees of the Imperial War Museum and the Director and Council of the National Army Museum, who hold copyright over a number of the accounts used in the book. I was kindly assisted in accessing material held by Harrods by company archivist Sebastian Wormell.

The following individuals also deserve a mention either for loaning me original material or for their kind offers of support and encouragement; John and Tony Begg, Malcolm Brown, Anna De, Bruce Dennis, Francis Mackay and Peter Saunders. Finally, I would like to thank my wife Julie for assisting with the book and for putting up with losing me to the computer on numerous evenings and weekends.

Introduction

The outbreak of war in August 1914 was generally greeted by the peoples of the European great powers with enthusiasm and euphoria. Patriotism surged through the nations of Europe and a sense of national unity manifested itself even in countries such as Austria-Hungary and Russia, where deep-seated political and social divisions existed that had not long before looked likely to split these nations apart or lead to civil war and revolution. Instead, political ceasefires were called as everyone lined up behind the governments and ruling elites of the day. Both war planners, political leaders and the populace at large believed the war would be short and victorious for their side. In any case, many believed that it would be impossible for modern industrial nations to fight a long war because of the disruption this would bring to their economies, which were linked in a highly interdependent system of international trade. Few had the foresight to see that once the resources of modern industrial states were fully harnessed for war a very different outcome could follow.

In Britain the phrase ‘all over by Christmas’ was much uttered, and similar stock phrases could no doubt be found for the other warring nations. However, there would be almost another four wartime Christmases to follow that first one before the conflict was resolved. The war grew to encompass the Mediterranean, Middle East and Africa and became a more industrialised and intensive conflict through the ever growing use of artillery and the introduction of such weapons as gas, tanks and purpose-built bombing aircraft. Through all this the citizen soldier, who made up the bulk of most of the armies, whether he be a volunteer, conscript or reservist recalled to the colours, found solace in many of the simple things in life that could, even for a short time, take his mind off the situation in which he found himself and brought forward thoughts of home, family and life before the war. Christmas, an important annual celebration and holiday in many of the combatant nations, provided an obvious opportunity for troops to focus on something other than the war. Although birthdays and other personal celebrations provided important links with home and a chance for soldiers to celebrate, the ‘national’ and ‘international’ status of Christmas allowed for large-scale festivities involving whole battalions or regiments. Such activities, generally taking place behind the lines when units were on rest, were encouraged by the High Command as morale-boosting exercises; the troops were given time off, plentiful food and drink and organised activities such as sport and concerts.

If sharing Christmas cheer with your comrades and allies was actively supported by the military authorities, then attempts to share the compliments of the season with the enemy was viewed with great alarm by senior officers and war leaders as they feared their troops’ fighting spirit would be undermined by fraternising and temporary truces with the enemy. Following the events of the now famous Christmas Truce of 1914, extensively covered in the excellent book by Malcolm Brown and Shirley Seaton,1 much effort was expended to prevent such contacts being established again. Although these worked to a large extent, limited open contacts with the enemy and a whole system of more covert trucing, which became known as the ‘live and let live’ system, developed between soldiers sharing the same conditions and hardships in the front line.2

Through the use of photographs, illustrations and the words of soldiers themselves this book will attempt to give a flavour of how Christmas was celebrated by British forces during the First World War. The objective is to look beyond the 1914 Christmas Truce, by covering the following four years and the experiences of those serving in theatres of war beyond France and Flanders, such as Gallipoli, Italy, Mesopotamia, Palestine and Salonika. In this way the book provides a glimpse of the different Christmas experiences a soldier could have during the four years of war. There are accounts by those serving behind the lines, the wounded in hospital, prisoners of war, men training in Great Britain and those on garrison duty in that jewel in the crown of the British Empire, India. Christmas 1918 is also included as many troops were still overseas awaiting demobilisation, on duty with forces of occupation in Germany, Turkey, Bulgaria and parts of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire or fighting against the Bolsheviks in various parts of Russia. This qualifies it very much as a ‘wartime’ Christmas and thus worthy of inclusion here. Each year of the war is given a chapter in which an overview of the progress of the conflict provides the background against which the words of the soldiers and illustrative material tell the story of Christmas in the trenches from 1914 to 1918.

Each first-hand account used in this book is referenced by the individual’s name and unit and the repository in which the material is held. Footnotes cover only published works or where a specific letter or other document from a larger collection has been cited. In the text, each account is accompanied by the name of the individual or unit to which it relates. All ranks and unit designations used relate to the time of the events described. Unless stated otherwise, illustrative material comes from the Photographs Archive and Department of Documents at the Imperial War Museum.

The First Christmas: 1914

In offering to the Army in France my earnest and most heartfelt good wishes for Xmas and the New Year, I am anxious once more to express the admiration I feel for the valour and endurance they have displayed throughout the campaign and to assure them that to have commanded such magnificent troops in the field will be the proudest remembrance of my life.

Sir John French’s Special Order of the Day, issued to the BEF, 25 December 1914

In December 1914, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was holding a line some 30 miles in length from St Eloi, just south of Ypres, down to Givenchy on the La Bassée Canal. Crossing much of the area was a system of drainage ditches and watercourses that prevented this low-lying land from flooding. Unfortunately, artillery fire and the construction of trenches had damaged much of this network with the result that, once the winter weather arrived, the area began to be transformed into a morass. The hastily dug trenches offered little in the way of comfort:

I have just come out of 2 days and 2 nights in the trenches. I wonder how many people realize what the trenches are like. In some newspapers one sees accounts of hot soup and wonderful fires etc. In some places the mud came over my knees. This is not exaggerated. In most places over ones ankles. The first night it was horrid, raining all night. No room to move. It is really wonderful what the Tommy stands . . . You should have seen us coming out – all mud from head to foot, sore feet and heavy equipment. But are we downhearted? Not one!1 (2/Lt Wilbert Spencer, 2nd Wiltshires)

As both sides struggled to keep their trenches dry the intensity of trench fighting died down and small-scale ad hoc truces began to occur in some sectors of the line with both sides refraining from firing during mealtimes and at ration-carrying parties. Following spells of the worst weather, small working parties on each side could be observed working in the open repairing trenches and breastworks with little interference from those on the ‘other side of the wire’. The closeness and constant presence of the enemy in trench warfare bred a curiousness and realisation that the enemy was suffering exactly the same conditions. Through this the ‘live and let live system’ started to develop, whereby many opposing units made daily life more bearable by reducing the general level of violence:

Things up here are very quiet – in my part of the line the trenches are only 50 or 60 yards apart in places, and we can hear the Germans talking. They often shout to us in English and we respond with cries of ‘waiter’. There was one fellow who had a fire with a tin chimney sticking up over the parapet and our men were having shots at it with their rifles. After each shot the German waved a stick or rang a bell according to whether we hit the chimney or not! There are lots of amusing incidents up there and altogether we have quite a cheery time our worst trouble is the wet and mud which is knee-deep in some places.2 (2/Lt Dougan Chater, 2nd Gordon Highlanders)

This is not to say that troops were guaranteed a quiet time in the line. Artillery bombardments still fell on occasion, although a shell shortage generally confined heavy gunfire to offensive operations and trench raids. Of greater concern were snipers who, during this relatively quiet period, were usually waiting to account for the unwary and the careless. At Fleurbaix for example:

These snipers seldom missed. Their guns were fixed during the day to aim at a certain spot, and then during the hours of darkness they would fire at short irregular intervals, hoping to catch some of us who were moving about. Shallow parts of the trench and the holes in the convent wall immediately behind us were their favourite targets. Working and ration parties used to congregate behind the wall, owing to the communication trenches being full of water, and woe betide anyone who forgot for a moment and in the darkness stood in a gap in the wall instead of actually behind it . . . (Pte W.A. Quinton, 2nd Bedfords)

With the realisation that they would still be on active service over Christmas, the soldiers’ thoughts naturally turned to home and to how they could best celebrate the festive season under such trying circumstances:

I should like the pudding sent off soon or else it may not reach me in time for Christmas. I don’t know whether I shall be able to eat it on Christmas Day or not, it all depends on whether we happen to be in the trenches or not on that day. If we are not we will have pheasant and the puddings which will be very near the ordinary Christmas fare except for the company and the decorations but still we shall have to institute another Christmas when we come back and have all the festivities over again.3 (Rfm Richard Lintott, 1/5th Londons)

Parcels and Christmas gifts would not only come from families and friends; regimental associations, counties, towns and cities also supplied their fighting men with useful articles. Rfm Lintott, for example, received three khaki handkerchiefs, a tin of Abdullah cigarettes, a cigarette lighter and writing paper from the people of Horsham and a ½ lb tin of butter, a tin of milk, a tin of cocoa, a handkerchief and a case of writing material from his regiment. Among the gifts came one of the most enduring mementos of the First World War, the Princess Mary Gift Box. This was to be given to all those wearing the King’s uniform on Christmas Day 1914: some 2,620,019 men in total. With such a huge number of gift boxes and their contents to be manufactured, distribution priority was given to members of the BEF in France and the Royal Navy. In total some 426,724 boxes were received on Christmas Day, the remainder being issued subsequently.4 That this gift, along with a Christmas card from the King and Queen, was appreciated by the troops is shown by the mentions it receives in letters, diaries and memoirs as well as the fact that many men repacked the tins and sent them home to their families for safe keeping.

The arrival of Princess Mary’s gift coincided with one of the most widely known events of the war, the Christmas Truce. Until the evening of 24 December the weather had been generally very wet. However Christmas Eve brought a sharp frost, causing the ground to harden and thus easing mobility, a factor that would prove important the following day. As Christmas drew near even headquarters slackened their workloads; for example, at 4th Division HQ a communication was sent out to all units stating that owing to Christmas the divisional signals service would only deal with priority messages during the night of 25–26 December.5 For British troops in many parts of the line, strange activity on the part of the Germans soon became apparent:

As darkness came on lights were seen in the German lines in the Rue du Bois, at first our fellows fired at them and the Germans put them out – gradually the firing died down, and all the enemy sniping ceased. The silence was almost uncanny and we were all very suspicious and extra vigilant, expecting some trick. Later on lights began to appear in the German trenches and their whole line was illuminated. I think they had hoisted lanterns on tall poles on their parapet and in their trenches. After that they began to sing . . . finishing up with the Wacht am Rhein, the German and Austrian national anthems. They sang beautifully the whole effect was weird in the extreme. They then started shouting remarks across to us which we replied, but I could not hear what was said. I think everyone felt very homesick on Xmas Eve. Thoughts of our families at home were uppermost in our minds.

The night passed without a shot being fired on either side. Our sentries were however extra vigilant and I felt quite uneasy at the strange silence. (Maj Q. Henriques, 1/16th Londons)

The activity opposite the 1/16th Londons stopped some men from the battalion giving the Germans a special seasonal gift:

We had decided to give the Germans a Christmas present of 3 carols and 5 rounds rapid. Accordingly as soon as night fell we started and the strains of ‘While Shepherds’ (beautifully rendered by the choir) arose upon the air. We finished that and paused preparatory to giving the 2nd item on the programme, but lo! We heard answering strains arising from their lines. Also they started shouting across to us. Therefore we stopped any hostile operations and commenced to shout back. One of them shouted ‘A Merry Christmas English, we’re not shooting tonight’. We yelled back a similar message and from that time on until we were relieved on Boxing morning at 4am not a shot was fired. After this shouting had gone on for some time they stuck up a light. Not to be out done so did we. Then up went another, so we shoved up another. Soon the two lines looked like an illuminated fete. Opposite me they had one lamp and 9 candles in a row. And we had all the candles and lights we could muster stuck on our bayonets above the parapet. At 12.00 we sang ‘God save the King’ and with the exception of the sentries turned in.6 (Rfm Ernest Morley, 1/16th Londons)

With generally friendly relations established through the previous evening’s verbal advances the scene was set for the more adventurous souls on each side to move the truce to another level:

On Christmas Day the Germans stuck up a white light and shouted that if we refrained from firing they would do the same. We did so and people started showing themselves over the trenches and waving to each other. Shortly 2 Germans advanced unarmed towards our trenches and our men did the same. They met ½ way and shook hands, exchanged cigarettes and cigars and souvenirs and soon there was quite a big crowd between the trenches, we 3 included. Russell was introduced to a barber in the Strand named Liddle (spelling phonetic). Another German asked Russell in good English if he would like to go home. Russell asked him where he lived and the chap said London and hoped he would soon be able to return there. Both sides then buried the dead whom they had been unable to get at before, after which the Germans were ordered back to their trenches. Both sides continued to expose themselves, however, and to hold amiable conversations, and when we were relieved this morning not a shot had been fired on either side in our trenches though we could hear firing on both flanks and the artillery were bombarding each other over our heads.7 (Rfm Jack Chappell, 1/5th Londons)

In some sectors the need to bury the dead was a central factor in the truce taking place. Near Frelinghien, the 2nd Monmouthshire Regiment were holding the line:

Just imagine our feelings when we thought of home and looked out at our bleak surroundings. A yard or so from where I was standing a German soldier had been buried, and his foot had actually been sticking out in our trench until we had covered it up with earth. The stench at times was almost unbearable. (Sgt Francis Brown)

In some places the opposing troops joined together in paying their respects to the dead:

Near where we were standing a dead German who had been brought in by some of the English was being buried and a German officer after reading a short service in German, during which both English and Germans uncovered [their heads, he said], ‘We thank our English friends for bringing in our dead’ and then said something in broken English about a Merry Xmas and Happy New Year. They stuck a bit of wood over the grave – no name on it only ‘Vor Vaterland und Freheit’ (for Fatherland and Freedom). After a little while the German officers called their men in and we went back to our breastworks, calling in at a shelled out estaminet on the way to loot a chair and one or two other articles.8 (Rfm Selby Grigg, 1/5th Londons)

Although cordial relations were established across No Man’s Land in many places, the truce was not universal and casualties were therefore inevitable. One of these unfortunate men was Sgt Frank Collins of the 2nd Monmouthshires:

About 8am voices could be heard shouting on our right front, where the trenches came together to about 35 yards apart, German heads appeared, and soon our fellows showed themselves and seasonal greetings were bawled back and forth, evidently Xmas feeling asserting itself on both sides. Presently a Sergt. Collins of my Regiment stood waist high above the trench waving a box of Woodbines above his head. German soldiers beckoned him over, and Collins got out and walked half way towards them, in turn beckoning for someone to come and take the gift. However, they called out ‘prisoner’ and immediately Collins edged back the way he had come. Suddenly a shot rang out, and the poor Sergt. staggered back into the trench, shot through the chest. I can still hear his cries ‘Oh my God, they have shot me’, and he died immediately. (Sgt Francis Brown)

Despite the bitterness caused by the shooting, the truce held on the Monmouthshires’ sector of the line and at 9 a.m. Welshmen and Bavarians exchanged gifts and season’s greetings, with many of the Germans apologising for the shooting. Sgt Collins now lies in Calvaire (Essex) Military Cemetery, Comines-Warneton, 16km from Ypres on the road to Wijtschate and Ploegsteert.

After Boxing Day, although meetings in No Man’s Land became rarer, opposing troops who had fraternised maintained the ‘live and let live’ attitude, with little in the way of hostilities. In places it was even arranged to have another truce on New Year’s Day, 2/Lt Chater remarking in a letter to his mother that the Germans requested this in order to see how photographs taken on Christmas Day had turned out.9 For Germans, New Year brought the feast day of St Sylvester, a traditional family holiday. However, one German practice of welcoming in the New Year did lead to some misunderstanding:

. . . things went smoothly till the night of the 31st. New Year’s Eve. On this night we decided to remove our M.G. to a new position some couple of hundred yards or so along the trench, as we had a notion that the Germans knew of its present position, and would not hesitate to shell us out as soon as hostilities recommenced. Having prepared the new gun-pit the previous night, we now made ready for the moving, and still being on friendly terms with the enemy, and our trenches being knee-deep in mud and water, we took the easiest course and travelled along the top behind our own trench. We started off, well loaded with all our kit, the gun, tripod, and boxes of belt ammunition, and our rifles slung across our backs by the slings. We made very slow progress as the ground was very heavy with mud (the snow having thawed) and in addition to this we had to negotiate the communication trenches that ran at right-angles to the firing-line. These were about 4ft wide and we crossed by taking a sort of staggering leap, and throwing the heavy stuff across to the outstretched arms of those already over.

An hour had passed and we had covered about three-parts of the total distance, when without a word of warning something happened that caused us to fall as one man, flat on our stomachs in the mud. The Germans had opened fire! Rifles and machine guns cracked. They had done the dirty on us! We crouched there in the mud, and the names we called those Germans must have turned the air blue. Yet, strange, we could not feel the ‘pinging’ of any bullets around us? The explanation came in the next few moments, when a voice from our front-line yelled ‘Hi you fellows, what’s up? They ain’t firing across ’ere. They warned us what they were going to do. They’re firing in the air to celebrate the coming-in of the New Year.’ . . . Having made sure that the voice from the trench had spoken the truth, we staggered to our feet and continued our journey. How easily mistakes can be made! Being out of the trench we did not know of this midnight arrangement, and it was lucky for the Germans that we had not misunderstood their intentions, and opened fire on them with our machine gun. This certainly would have broken up the temporary armistice.

And so this unofficial armistice with the enemy still held good. (Pte W.A. Quinton)

When news of the truce reached senior officers there was something of a mixed reaction. A report of IV Corps operations between 22 and 31 December 1914 records that German overtures for a temporary halt to hostilities were not entertained by the 8th Division, whereas the Gen Officer Commanding (GOC) 7th Division, Maj Gen Sir Thompson Capper, sanctioned the continuation of the truce on 26 and 27 December to allow adequate time for burial of the dead and drainage of watercourses and trenches, so as to improve the condition of the front line, the proviso being that no unit was to arrange any further formal or informal truce without reference to Corps HQ.10 Once such work was completed, commanders on both sides realised they had to get the war started again before the fighting spirit of their men was permanently affected. On the German side an army order of 29 December declared that any act of fraternisation with the enemy would be treated as high treason. Similar, though less dramatic, was Gen Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien’s 2nd Army instruction stating that any officer or NCO allowing informal understandings with the enemy would be tried by court martial. With orders arriving to begin vigorous artillery bombardment, sniping and machine gunning of the enemy, soldiers realised this brief interlude in the war was almost over. Some, however, were determined to ease their way back into the war, causing as little harm as possible to their new ‘friends’ on the other side of the wire:

The war was becoming a farce and the high-ups decided that this truce must stop. Orders came through to our Brigade, and so to my battery, that fire was to be opened the following morning on a certain farm which stood behind the German support line. Our battery was to put twelve rounds of high explosive shell into it at eleven o’clock. As luck would happen, I was the officer who would have to do this. So I said to Johnny Hawkesley, ‘What are we going to do? They’ll all be there having coffee at eleven o’clock! I see them every morning from my O.P. through my telescope.’ So he said ‘Well, we’ve got to do it, so you’d better go up and talk to the Dubs about it.’

I went up and saw Colonel Loveband, who commanded the Dublin Fusiliers, and he sent someone over to tell the Boches, and the next morning at eleven o’clock I put twelve 18s into the farmhouse, and of course there wasn’t anybody there. But that broke the truce – on our front at least. (2/Lt Cyril Drummond, 32nd Brigade, RFA)

From evidence in brigade, divisional and corps war diaries of the BEF for December 1914 it is obvious that a number of officers feared censure over the truce. Indeed, Smith-Dorrien had threatened action over reports of trucing that he learnt of on Boxing Day. Therefore reports sent up to senior commanders for the Christmas period stressed the usefulness of the truce as an intelligence-gathering exercise:

Germans making a great deal of noise last night singing and shouting. Some came towards our line and called for our men to go over to them. Two or three men went over and spoke to them and got quite close to their trenches. They reported farm S of LA of LADOUVE occupied with considerable number of Germans round it and a number more singing east of avenue. Some of them are reported to have been wearing picklehaubes mostly caps or woollen helmets and some khaki covered shakos. Regtl number on shoulder thought to be 10 and 25. This morning several came up towards our trenches in the mist but were ordered back and warned that they would be fired at. Their Regtl numbers were 7 with green facings and shako, 134 with red facings and 10 with red facing, both the latter with caps. No helmets were seen. Reported that no wire between us and them that we cannot see. No firing at all today. R E wired right across left section last night. We have been wiring and cleaning up in the mist. (Report from 2nd Seaforth Highlanders, 10th Infantry Brigade to HQ 4th Division)11

Along with regimental identifications came information on the age and apparent fitness of enemy troops, the strength in which they were holding the front line, the state of the enemy’s trenches, locations of machine guns and sniping positions. It was even recorded that a Lt Belcher of the 1st East Lancashires talked with a sniper, asking him where he generally fired from so that he could have a pot at him, but the man was not fool enough to give the show away.12 General information gleaned from German newspapers, exchanged during the truce, was also sent up the chain of command as evidence of German morale at home and attitudes towards the British.