Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

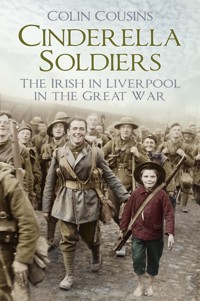

Based on extensive research, Cinderella Soldiers uncovers the experiences of the Liverpool Irish Battalion during the Great War. The ethnic core of the battalion represented more than mere shamrock sentimentality: they had been raised within the Catholic Irish enclaves of the north end of the city, where they had been inculcated and nurtured in Celtic culture, traditions and nationalist politics. Throughout the nineteenth century, the Irish in Liverpool were viewed as a violent, drunken, ill-disciplined and disloyal race. These racial perceptions of the Irish continued through the Home Rule Crisis which brought Ireland to the cusp of civil war in 1914. This book offers a different account of an infantry battalion at war. It is the story of how Liverpool's Irish sons, brothers, fathers and lovers fought on the Western Front and how their families in the slums of Liverpool's north end experienced and endured the war.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 490

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2019

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Colin Cousins, 2019

The right of Colin Cousins to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9124 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

List of tables

List of maps

List of abbreviations

Preface

Introduction

1 Liverpool 1914: Division, Recruitment and Unity

2 Trench Life, Patrols and Raids

3 Officers, Men and Morale

4 Discipline and Leadership

5 Battlefronts: Givenchy, the Somme and Passchendaele

6 Kultur and Captivity

7 Homefront

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Bibliography

Endnotes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My first debt is to Mr George Wilson whose interest in the battalion precedes my own by more than twenty years. Throughout that period, George amassed a vast dossier on the battalion, comprising details of individual soldiers of the Liverpool (Irish) Battalion stretching from the Boer War to beyond the end of the Great War. I met George by way of a highly speculative enquiry to a London auction house. Since then he has been extremely generous in sharing his research material and invaluable expertise on the battalion. George had intended to write his own account of the battalion, and the fact that he was willing to share his research with someone he did not know is a remarkable testimony of his trust and generosity. I am indebted to George for his kind permission to use many of the sources from his research and to reproduce many of the images within his private collection.

I am grateful to the staff of the following institutions for their help and kind permission to use the sources and to reproduce many of the images contained in this book. In London: The National Archives, for permission to reproduce Haig’s Routine Order, the Imperial War Museum and for their kind permission to reproduce the images of the Western Front contained in this book. To the National Portrait Gallery, for their kind permission to reproduce the photograph of Brigadier-General Fagan; The Institution of Engineering and Technology Archives for permission to use the image of Lieutenant H.L. Downes and Aberdeen University Museums and Special Collections for permission to use the image of Captain J.E. Milne. I am also grateful to the staff of Liverpool Central Library and to St Helens Library, for their kind permission to reproduce the recruiting poster of the Liverpool Irish; the Wellcome Archives, Army Medical Museum, Aldershot, and the Wolfson Centre at Birmingham Library. My thanks are also due to the staff at the National Library of Ireland, University College Dublin and the Bureau of Military History, Dublin. Further afield, I am indebted to the Australian War Museum for their permission to reproduce the image of Private Lambert and to the International Committee Red Cross, Prisoners of the First World War Archives.

I am much indebted and grateful to the following copyright holders for their kind permission to use photographs, letters and diaries: Tom Fisher for his kind permission to quote from the George Tomlinson papers and to reproduce George’s photograph; Mr Ian McIntosh, for his permission to use the James Green papers; Patricia Normanly, Dublin, for permission to use Private James Jenkins’ photograph and background information. I am also very grateful to Mrs Anne Hayton, for the Moynihan papers and photograph of Lieutenant Moynihan; M. Geerhard Joos, Brent Whittam and Terry Heard, at https://www.ww1cemeteries.com, for their assistance concerning war graves and for Geerhard’s kind permission to use his photograph of Private Joseph Brennan’s grave; to the Headmaster of Stonyhurst College for his kind permission to use the photograph of Captain H.M. Finegan. I am also grateful to Joe Devereux and Kath Donaldson, Liverpool, for their comments and knowledge of Liverpool soldiers during the Great War. I had some help in preparing this book for publication and I am very grateful to Nicola Guy at The History Press, and Averill Buchanan in Belfast for her advice and for compiling the index. My gratitude is also due to Sandra Mather, formerly of Liverpool University, for her cartographic skills in producing the maps contained in this book. All maps in this book are the copyright of Sandra Mather.

My final debt is to my wife Linda for her long-suffering indulgence of my fascination with the Great War. Hopefully, the fact that this book relates to her native city is of some minor consolation.

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 Irish-born residents of Liverpool 1841–91

Table 1.1 Home districts of 100 men enlisted in the 8th (Irish) Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment

Table 1.2 Occupations of 100 men of the 8th Liverpool (Irish) Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment

Table 1.3 Home districts of 100 men enlisted in the 8th (Irish) Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment

Table 1.4 Occupations of 100 men of the 8th Liverpool (Irish) Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment

Table 3.1 Summary of accidental and self-inflicted casualties, 55th (West Lancashire) Division, February–July 1916

Table 4.1 Death sentences passed on soldiers of the 8th (Irish), Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment, 1914–1918

Table 4.2 Disciplinary record Private Joseph Brennan

Table 4.3 Total number of death sentences passed and number of executions in all battalions of the King’s Liverpool Regiment 1914–18

Table 4.4 Total number of offences tried by Field General Courts Martial for all battalions of the King’s Liverpool Regiment 19 May 1915–21 September 1916

Table 5.1 Somme battle casualties for three battalions of 55th (West Lancashire) Division, 27 July–29 September 1916

Table 6.1 Strength of British Army and total numbers of British soldiers killed in action and prisoners of war, 1914,1916 and 1918

LIST OF MAPS

Map 1 Electoral Districts of Liverpool c.1900

Map 2 The dispositions of the 55th Division at Blaireville prior to the trench raid by the Liverpool Irish on 17/18th April 1916

Map 3 The objective of the Liverpool Irish at Rue D’Ouvert, 16 June 1915

Map 4 Artillery map of Guillemont on the Somme indicating the dispositions of 164th and 165th Infantry Brigades on 8 August 1916

Map 5 Battle of Pilckhem Ridge. Map showing the objectives of the 55th Division 31 July–2 August 1917

Map 6 Compiled from hand-drawn sketch detailing the topography and events around the areas of Schuler and Wurst Farms 31 July–2 August 1917

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ASC

Army Service Corps

BEF

British Expeditionary Force

BMH

Bureau of Military History

Capt.

Captain

CCS

Casualty Clearing Station

CO

Commanding Officer

Col.

Colonel

Coy

Company

Cpl.

Corporal

CPWHC

Central Prisoners of War Help Committee

CSM

Company Sergeant Major

CQMS

Company Quartermaster Sergeant

CYMS

Catholic Young Men’s Society

DCM

Distinguished Conduct Medal

DCM

District Court Martial

DSO

Distinguished Service Order

DOW

Died of Wounds

FGCM

Field General Court Martial

FP

Field Punishment

GCM

General Court Martial

GHQ

General Headquarters

GOC

General Officer Commanding

GSW

Gun Shot Wound

INV

Irish National Volunteers

IPP

Irish Parliamentary Party

IRB

Irish Republican Brotherhood

IWM

Imperial War Museum

KIA

Killed in Action

Lt.

Lieutenant

Lt. Col.

Lieutenant Colonel

MC

Military Cross

MIA

Missing in Action

MM

Military Medal

MO

Medical Officer

NBSP

National Brotherhood of St Patrick

NCO

Non-Commissioned Officer

OCB

Officer Cadet Battalions

OTC

Officer Training Corps

POW

Prisoner of War

PWHC

Prisoners of War Help Committee

Pte

Private

RAMC

Royal Army Medical Corps

RASC

Royal Army Service Corps

RCM

Regimental Court Martial

Sgt.

Sergeant

TNA

The National Archives

UVF

Ulster Volunteer Force

VC

Victoria Cross

VD

Venereal Disease

PREFACE

The ‘national amnesia’ surrounding Ireland’s participation in the Great War has undergone an extensive period of rehabilitation throughout the last decades of the twentieth century. Sadly, the wartime experiences of Irish exiles in Britain have been ignored and neglected. This is certainly true in respect of Liverpool’s massive Irish population.

The Irish contribution to military life in Liverpool emerged in 1860 with the creation of the Volunteer movement in the city. Originally designated as the 64th Liverpool Irish Volunteer Corps, their creation came about just thirteen years after the great influx from famine-stricken Ireland. Between its creation and the Great War, the popularity of Liverpool’s part-time Irish soldiers endured a series of peaks and troughs which were closely aligned to events in Ireland or related to the sectarianism of their host city. While most British Army regiments or battalions enjoyed close relationships with their native towns and cities, the Liverpool Irish part-time soldiers had an inextricable ethnic affinity with the north end of Liverpool and Ireland itself. In attempting to recover the narrative of the 8th (Irish) Battalion during the Great War, it has been impossible to sever the ethnic and social bonds which attached the battalion to its Celtic enclaves and Ireland.

Occupying ‘a curious middle place’, the Irish in nineteenth-century Liverpool were at once exiled from their native country and ostracised within their host city. Located in the north end of Liverpool, they constituted an isolated Celtic residuum whereby they could live in the city and yet remained apart from it. They inhabited the courts and cellars of Scotland Road and its environs which prior to their arrival had been deemed as unfit even for the city’s slum dwellers. The Irish propensity for drinking and fighting invited newspapers and journals to portray them as filthy, drunken and violent. Second and third generations of Liverpool Irish, reared within the city’s Irish enclaves, still identified themselves as Irish despite never having visited their ancestral island. The fact that they had been born in Liverpool was immaterial, as Liverpool’s Irish children were immersed in a patriotic Celtic culture and became ‘sternly Irishised’. During the virulent ‘No Popery’ campaign, their Catholic faith became synonymous with their Irishness. Nationalist uprisings in Ireland in 1798 and 1848 and the Fenian scares of the 1860s tainted the Liverpool Irish with suspicions of disloyalty. Sectarian clashes and political tensions surrounding the Home Rule crisis in the years leading up to the Great War meant that Liverpool, like Belfast, was a divided city.

Following the declaration of war in August 1914, as a territorial unit, the 8th (Irish) Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment could have opted for Home Service; instead, they volunteered to fight abroad. When the good people of Liverpool rallied to supply the city’s fighting men with comforts, the local press reminded them that many of the Liverpool Irishmen came from impoverished backgrounds and therefore did not receive as many comforts as those serving in middle-class units; the papers declared that there should be no ‘Cinderella battalion’ in Liverpool.

This book is an attempt to recover the story of how the Liverpool Irish and their Cinderella soldiers endured the Great War.

Map 1: Electoral Districts of Liverpool c.1900.

INTRODUCTION

The Irish in Liverpool: The Social and Political Background

The popularity of Liverpool as the location of choice among Irish migrants is evident even in the years prior to the famine influx of 1847. In 1841, the city had an Irish-born population of nearly 50,000. It was during the following decade, with the devastation caused by the Irish potato blight and resultant hunger and destitution, that the numbers of Irish-born inhabitants in Liverpool escalated to nearly a quarter of the total population. Wealthy nineteenth-century-Liverpool justifiably wallowed in civic pride; it was, after all, a thriving port and a centre of trade and commerce where the sweat, clamour and commotion of the docks contrasted with the halcyon atmosphere of the nearby business districts. Liverpool was also a city of contrasting sobriquets; it was known as ‘the Second City of the Empire’,1 and the ‘gateway to America’.2 It was also, rather less obsequiously, described as ‘the black spot on the Mersey’3 and ‘the cemetery of Ireland’.4 A more recent and unflattering depiction of the city has been provided by the historian Don Akenson in An Irish History of Civilization: Volume two.5 Akenson, an eminent scholar on the history of the Irish diaspora, described mid-nineteenth century Liverpool as a ‘machine’. Akenson’s description (written, one suspects, with his tongue firmly in his cheek), stresses the important and significant role played by Liverpool in processing the multitudes of migrant Irish: ‘Liverpool in 1851 is second only to Dublin and Belfast in the number of Irish-born inhabitants. Some machine. Necessary. No one loved Liverpool, but if the devil had not invented it, some god would have had to.’ Many of the poorest migrants who left Ireland during the nineteenth century brought very little with them. They did, however, bring their poverty, their Irishness, their religion and politics. It was these characteristics which would unwittingly lead to conflict and half a century of tension and discord in their host city.

The geographical convenience of Liverpool across the Irish Sea, the expansion of its port, the growth of commercialism within the city and the development of steam-powered ships during the first quarter of the nineteenth century combined to make Liverpool an attractive destination for the disenchanted Irish.6 Whether reluctant migratory agricultural workers, labourers in search of work, or willing professional ‘micks on the make’,7 the Irish made their way to Britain to remain, or to board other ships bound for America or Australia. While economic necessity may well have been a significant factor compelling some to leave Ireland, hunger and destitution did not induce the Irish to cross the Irish Sea in the years before the famine. For the starving thousands of 1847 who had survived the trek from their rural homesteads to the Irish ports and endured the cramped conditions on their voyage across the Irish Sea, further challenges awaited them in Liverpool.

Many of those arriving at Liverpool had been weakened by malnutrition and the journey. Once ashore, an ethnic compass led them to the north end of the city where some 30,000 were packed into filthy overcrowded cellars in the densely overpopulated districts of Scotland Road, Vauxhall Road and Great Crosshall Street. In their desperation for accommodation, the homeless Irish smashed down the doors of cellars which had been condemned as uninhabitable and sealed by the council.8 These congested and unsanitary conditions were all that was available to the starving Irish in the 1840s. Slum housing also provided ideal conditions for the spread of diseases such as typhus, dysentery and measles. Statistics of the rates of infection were overwhelming and the city of Liverpool struggled to cope with the disaster. During 1847, some 60,000 people had been treated for typhus, while a further 40,000 suffered from dysentery and diarrhoea.9 Around 8,500 of those 100,000 died, and Frank Neal has estimated that 5,500 of those who had died were Irish famine refugees.10 Given the scale of the influx of famine refugees and the resulting epidemics during 1847, it is morbidly fitting that the Register General of Births Deaths and Marriages described Liverpool as ‘the cemetery of Ireland’.11

The Irish who chose to remain in Britain began their search for employment, self-fulfilment or mere survival, have been described as ‘a restless, transient people.’12 Some educated Irish immigrants moved south from Liverpool to London, or to wherever their talents were in demand. Other, unskilled workers, travelled inland through Lancashire to the manufacturing centres such as Manchester and its environs.13 Protestant Irish migrants of the mercantile class appear to have discovered Liverpool early in the nineteenth century, unlike their less fortunate Catholic countrymen, and they possessed not only the means but the will to integrate themselves within Liverpolitan society.14 While Liverpool was undoubtedly a thriving port and an important centre for commerce, it lacked the major manufacturing industries of other northern English cities. Predictably, many of the low-skilled Irish settled in those areas close to the employment opportunities provided in the docks of Liverpool.15 Thus, the Irish established themselves in the north end of Liverpool which comprised the political wards of Scotland, Vauxhall, Exchange and St Paul’s.16

Table 1:Irish-born residents of Liverpool 1841–91

Year

Population

No. of Irish-born

Irish as % of the population

1841

286,656

49,639

17.3

1851

375,955

83,813

22.3

1861

443,938

83,949

18.9

1871

493,405

76,761

15.5

1891

517,980

66,071

12.6

Source: Census reports, England, 1841–91.

Once established in the north end of the city, it was inevitable that a substantial second generation of Liverpool Irish would inflate the ethno-Celtic character of the city. Frank Neal has suggested that the number of Irish-born inhabitants of Liverpool in 1833 was 24,156 and that given the census total of almost 84,000 in 1851, the number of English children born to Irish parents was ‘relatively large’.17 To many native Liverpolitans and the local press, there was no distinction between native-born Irish and their offspring who were born in the city; they were all ‘Irish’.18 Table 1 reveals that there was a total of 49, 639 Irish-born residents in 1841 in Liverpool representing 17.3 per cent of the city’s population. Ten years later, in 1851, the numbers of Irish-born residents rose to 83,813, representing 22.3% of the population of Liverpool. By 1891, the numbers of Irish-born inhabitants fell to 66,071. However, these figures fail to include the offspring of the Irish-born residents of the city.

When the ships unloaded their vast malnourished human cargoes at the port of Liverpool throughout 1847, it was the city rather than the government which bore the financial burden of providing relief. This meant that the costs would fall on the businessmen and rate payers of Liverpool who were far from satisfied with this arrangement.19 In the years following the great influx, the Irish were put under a moral and social microscope where their appearance, behaviour, faith and habits were examined. Comments and reports were made in the local and national press, opinions were offered, and racial comparisons were made. Even the liberal Liverpool Mercury opined that the government could not ‘convert a slothful, improvident and reckless race’ except by means of ‘indirect action’ and ‘gradual process’.20 The article argued that responsibility for the famine and the cause of Irish misery lay with the Irish themselves due to their racial inadequacy: ‘There is a taint of inferiority in the character of the pure Celt which has more to do with his present degradation than Saxon domination.’ Racial stereotyping of the Irish continued throughout the nineteenth century. ‘Paddy,’ the reckless buffoon performing in the guise of a peasant or soldier, became the stock character on the London stage; he also appeared, more menacingly in cartoons as an ape. Steven Fielding concluded that, ‘The fully-fledged “simianisation” of the Irish occurred during the 1860’s.’21 The physical appearance and behaviour of the Irish inhabitants of the north end of the city attracted the attention of their fellow citizens and the local press in Liverpool. In one particularly venomous attack on the Irish populace of the north end, the Liverpool Herald claimed that the filth, drunkenness and criminal behaviour of the Irish was due to their nationality and their ‘papish’ faith:

The numberless whiskey shops crowded with drunken half-clad women, some with infants in their arms, from early dawn till midnight – thousands of children in rags, with their features scarcely to be distinguished in consequence of the cakes of dirt upon them … And who are these wretches? Not English but Irish papists. It is remarkable and no less remarkable than true, that the lower order of Irish papists are the filthiest beings in the habitable globe, they abound in dirt and vermin and have no care for anything but self-gratification that would degrade the brute creation … Look at our police reports, three fourths of the crime perpetrated in this large town is by Irish papists.22

Protestant anxieties had been heightened since the 1829 Catholic Emancipation Act. The Act, which was drafted with the intention of preventing civil war in Ireland by signalling an end of hostility towards the Catholic Church, ironically contributed to Protestant fears about Catholic influence and aggression.23

Few would have predicted that events in County Armagh during the late eighteenth century would influence the socio-political landscape of Liverpool up to, and beyond, the Great War. In 1795, the Orange Order emerged from a series of violent agrarian disputes which had plagued north Armagh during the last decades of the eighteenth century.24 The two opposing factions, the Protestant Peep O’Day Boys, who supposedly derived their title from their proclivity for making early morning raids on the homes of their adversaries, and the exclusively Catholic ‘Defenders’, had clashed in a series of brief yet bloody encounters prior to a defining battle which took place close to the Diamond at Dan Winter’s cottage near Loughgall in 1795. Having routed the Defenders, the victorious Peep O’Day boys resolved to form an organised body to protect themselves in the event of any further attacks. Thus, the Orange Order was born. Their erstwhile opponents did not disappear, rather they transformed into a secretive oath-bound society known as the Ribbonmen. Orangeism spread rapidly from its fountainhead in north Armagh to England and beyond. Donald MacRaild has suggested that the pace and distribution of the Orange Order throughout Britain was due to the migration of Ulster Protestants and militiamen returning from Ireland after the failed rebellion of 1798. Many militia units brought Orange warrants with them, which enabled them to establish lodges in their native districts. 25 The first Orange lodge in England was formed in Lancashire in 1798. 26 Five years later, the first public Orange procession took place at Oldham near Manchester in 1803. 27 By 1819, Liverpool had a grand total of three lodges which held their first procession in the city on 12 July that year.28 The Orangemen carried the lamb, the ark and bibles on poles; they also brought Catholic insignia which they burnt. Predictably, the local Irish Catholic inhabitants of the city took offence and violence followed, arrests were made, and several ringleaders were imprisoned for their role in the disturbance.29 Frank Neal has suggested that it was this first Orange parade in 1819 when sectarianism among the working class in Liverpool became institutionalised.30 In 1834, an Ulster-born Protestant cleric, the Reverend Mr Hugh McNeile, arrived at St Jude’s church in Liverpool.31 Controversial and eloquent, McNeile played a significant role in the No Popery agitation in mid-Victorian Liverpool. For McNeile, Popery was ‘religious heresy’ and a ‘political conspiracy’. McNeile went on to form the Liverpool Protestant Association which harnessed the city’s burgeoning sectarian culture.32 Liverpool Conservatives were quick to harness the concerns of the city’s Protestant working class and cultivate its support.33 Widely held perceptions that the Irish had driven down wages in the unskilled labour market contributed to sectarian tensions, and the associational Tory–Orange bonds served to protect the marginal privilege of the Protestant working class in Liverpool.34 The evolution of rabid sectarianism in nineteenth-century Liverpool had arrived at a juncture whereby ‘Catholic’ became interchangeable with Irish, and that any activity of an overtly Protestant nature became synonymous with Orangeism.35 If the Irish were maligned and treated with hostility, the feeling was mutual. The Jesuit poet-priest, Gerard Manley Hopkins, who had served at St Francis Xavier’s church in the city, recalled that in comparison with the Irish in Glasgow, the Liverpool Irish possessed an undying hostility towards their host city.36

The Irish in Liverpool enjoyed a drink. Whether it was for refreshment, conviviality or as a means to escape the miserable gloom of their slums, the Irish crowded into the pubs and beer houses of the north end. Given the sheer weight of their numbers, demand for alcoholic beverages among the Liverpool Irish was high, and the market duly responded by providing the means of supply. In 1874 there were 1,929 pubs and 383 beer houses in Liverpool.37 According to John Belchem, ‘Competition for custom was intense, particularly in Irish areas where publicans encouraged various forms of convivial and bibulous associational culture’.38 While many of the Irish tended to be unskilled labourers, Irish navvies possessed a talent for illicit distillation.39 Drunkenness and violence within the Irish enclaves was a problem for the police in the year preceding the famine, the triangle between Vauxhall Road, Great Crosshall Street and Scotland Road being a particularly dangerous one to police.40 Old enmities originating from long-standing family and territorial disputes had been transplanted from the villages and provinces of Ireland. Ultimately, these led to ‘Irish’ or ‘faction fights’ in the courts and streets of the north end and were often extremely violent.41 Throughout the nineteenth century the Liverpool Irish provided work for the police and kept the city’s courts and hospitals busy. Parades such as 12 July, when Liverpool’s Orangemen commemorated the Battle of the Boyne, or 17 March when the Irish celebrated their national saint, provided a physical representation of the religious and sectarian divide within the city where they frequently descended into riots.

Concerns about Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup d’état in France, and his expansion of the French Navy, led to a series of panics in the British press throughout the 1850s. Various military and political debates ensued as to how the French threat should be dealt with. It was agitation by the press and public opinion rather than any demands from politicians or senior military figures which led to the creation of the Volunteer movement in 1859.42 In the end it came down to cost. An increase in taxation would have been required to maintain the militia, whereas the establishment of Volunteers would cost nothing. Volunteers were raised under the Yeomanry and Volunteer Consolidation Act of 1804. The conditions of service were uncomplicated; prospective volunteers were required to take an oath of allegiance, and to attend eight drills within four months, or twenty-four drills within one year.43 The movement proved popular throughout the country and recruiting commenced in Liverpool. On 7 December 1859, a meeting was held at the London Hotel in the city to discuss the formation of ‘an Irish Volunteer Rifle Brigade’.44 Fifty men attended the event which was addressed by Captain Faulkner. He expressed the view that if a body of Irish Volunteers could be raised in the city, that it would be ‘the finest in the country and one upon which her Majesty might place the utmost dependence’. He then proposed the following resolution:

That in the presence of the armed demonstration now being made throughout this country, and to which our Scotch and Welsh fellow-subjects have respectively attached a distinctively national character, we, on the part of the Irish inhabitants of Liverpool, consider it our duty to form, after the model of our countrymen in London, a Liverpool Irish Volunteer Rifle Corps.45

The Volunteer movement served to provide prospective officers from Liverpool’s petite bourgeois Catholic community with an opportunity to enhance their personal profile within the city. More importantly, the establishment of an Irish contingent in the city demonstrated the willingness of the ‘low Irish’ to play an active role within their host city by representing their own community. Provisionally known as the Irish Volunteer Rifles, by April 1860 they were designated as the 64th (Irish) Volunteers and their numbers grew to 100 men. In September that year, they attended a review at Lord Derby’s estate at Knowsley Park. The 64th continued to recruit and by 1863 they had six companies comprising 600 men.46 These are very impressive figures. Just fourteen years earlier, Sir Arnold Knight, MD, addressed a meeting of the Health of Towns Association at South Chester Street in Liverpool. Commenting on the physical condition of prospective army recruits, Knight informed his audience that, ‘Out of every hundred young men who enlisted at Liverpool, for the army, three-fourths were rejected at Headquarters as unfit to be shot at’.47 If Knight’s statistics were correct, then either the diet of Liverpool’s Irish recruits had improved markedly during the intervening years, or the required physical standards for prospective recruits to the Volunteers were very low. After some initial changes in leadership, the 64th (Irish) Volunteers were eventually led by Captain P.S. Bidwell, a middle-class Roman Catholic corn importer. Bidwell was also a Liberal councillor for the Vauxhall Ward and therefore well known to his men. However, unlike many of his subordinates, Bidwell was opposed to Home Rule for Ireland.48

Within a few years, the 64th (Irish) Volunteers grew in respectability. Dressed in their rifle-green uniforms, the Volunteers were known within the Irish enclaves of Liverpool as the ‘Irish Brigade’.49 This peak of respectability within the city for the Liverpool Irish was to be short-lived. While many in the Liverpool Irish enclaves remained committed to their nationalist aspirations and constitutional politics, others were convinced proponents of physical force.50 The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a secret, oath-bound organisation, had its origins among the Irish exiles in America. Formed in 1858, Michael Doheny and John O’Mahoney wanted to explore the feasibility of organising a rebellion in Ireland and to organise an Irish-American invasion.51 The organisation, which came to be known as the ‘Fenians’, was organised in Dublin by James Stephens, a veteran of the 1848 rebellion.52 Liverpool, with its large Irish population and busy port, provided an ideal ‘halfway-house’ for Fenians or their sympathisers to smuggle men and munitions to and from Ireland or America.53 Launched in Liverpool in 1861, the National Brotherhood of St Patrick (NBSP), offered more sober and intellectual facilities to the Liverpool Irish away from the pubs and beer houses.54 However, the NBSP had among its membership a number of men with nationalist militant tendencies. It was these physical force nationalists who used the organisation as a cover for the Fenians in Liverpool.55 In September 1865, the Mercury reported that Fenians had managed to infiltrate the Volunteers:

It has been ascertained that numbers of Fenians, not only resident in Liverpool, but coming from Ireland and other places, have joined Volunteer corps in this town for the purposes obtaining knowledge of military drill, and that they have subsequently left and gone to Ireland for the purpose, it is supposed, of tutoring in military tactics the ‘boys’ who are to form the nucleus of the army of independence.56

While the report failed to identify any specific units, suspicion inevitably fell on the 64th (Irish) Volunteers. Research by Simon Jones into claims that the 64th (Irish) Volunteers had been infiltrated by large numbers of Fenians concluded that the allegations were without merit. Jones concedes that while many Liverpool Irish Volunteers might have harboured Fenian sympathies, the intelligence surrounding Fenian infiltration had been garnered from informants within the Irish drinking dens and they were eager to provide their police handlers with exaggerated accounts to ensure a good pay day.57 The reputation of the 64th (Irish) Volunteers was damaged further following clashes with the 12th Liverpool Artillery Volunteers (12th LAV), a neighbouring unit with a distinctly Orange hue. In July 1868, both units were on duty at an inspection of the 4th Liverpool Artillery Volunteers.58 When a member of the 64th attempted to cross the parade ground, he was prevented from doing so by men of the 12th LAV. The Liverpool Irishman was ‘bodily seized’ by men of the 12th LAV and pushed back. When the man eventually returned to his unit he told them what had occurred. Later, when both units approached the junction of Low Hill and Prescott Street, around thirty men from both units fell out of the ranks and a fight ensued. The Mercury reported that during the fight ‘the butt end of some of the rifles was used with telling effect upon the combatants of the opposing side’. Order was eventually restored when the police arrived. While the paper failed to provide any precise explanation of why the violence had erupted, it stated that one of the rumours circulating was that it had been initiated ‘from the exhibition of an orange-coloured handkerchief, which was regarded as an insult to the Catholic feeling of the Irish Brigade’.59 The status and reputation of the 64th Liverpool Volunteers suffered throughout the 1860s. Allegations that the unit had been infiltrated by Fenians and public exhibitions of indiscipline did nothing to improve their standing in the city. By 1873, Fenianism had faded and the IRB suspended its revolutionary activities. Later, the Brotherhood passed a motion when they agreed to ‘wait the decision of the Irish nation, as expressed by the majority of the Irish people, as to the fit hour of inaugurating a war against England’.60

By 1871, the numbers of Irish migrants had fallen to 76,761, although the figures for second and third generations of Liverpool Irish increased.61 The rise in numbers of Liverpool-born Irish impacted on municipal politics within the city. In 1875, the Scotland electoral division was won by Lawrence Connolly, who had campaigned on an Irish nationalist ticket. The influence of the Liverpool Irish within Liverpool’s council chamber grew between 1875 and 1922.62 After Connolly’s victory in 1875, a total of forty-eight Irish nationalists served on the city council. In 1885, another nationalist, T.P. O’Connor, was elected as MP for the Scotland Ward. Thomas Power O’Connor, also known as Tay Pay, ‘who, at a little distance looked like a Jap’, was urbane, eloquent and a prolific journalist. Although more at home in cosmopolitan London, O’Connor was regarded as a hero among his Irish constituents in Liverpool’s Scotland Road. 63 O’Connor’s reign was to be a long one, lasting until 1929. In case any prospective Liverpool Irish voters were in doubt as to where their loyalties lay, George Lynskey, an Irish nationalist councillor, urged them to remember that they ‘were Irish first and Liverpudlian after’.64 Harry Sefton reminisced about his childhood on Scotland Road, recalling the local atmosphere and blatant irregularities on polling day:

Elections were carnivals. There were the larks of the ‘Bhoys’ eminently practical; their slogan was: Vote Early and Vote Often! Wherefore on polling days scores of long-dead voters came dutifully from their graves to exercise their franchise.65

This period also saw changes to the 64th Liverpool Irish Volunteers. Inexplicably, the battalion moved its headquarters to 206 Netherfield Road in 1876. This was an interface area which marked the dividing line between the orange and green populations in the north of the city. Unsurprisingly, several clashes occurred between members of the battalion and local ‘Orange roughs’.66 In 1880, their title changed when they became the 18th Lancashire Volunteers (Liverpool Irish). Just eight years later, under the reforms instigated by Lord Cardwell, the Secretary of State for War, they were renamed the 5th (Irish) Battalion, King’s (Liverpool) Regiment.67 Frank Forde asserts that the organisational changes made no impact on the battalion; they still dressed in the black-buttoned, rifle-green uniforms modelled on those of the Royal Irish Rifles. Their regimental march also remained unchanged. Long before the Hollywood era of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the 7th US Cavalry, the Liverpool Irish continued marching past to the strains of Garryowen.68

The battalion continued to thrive during the final decades of the nineteenth century. On Sunday 20 June 1897, they attended Queen Victoria’s Jubilee celebrations at Wavertree Playground where 7,000 men paraded in front of a crowd of 60,000 spectators.69 High Mass was celebrated and the 5th (Irish) Battalion’s chaplain, Monsignor Nugent, officiated while the battalion’s band played throughout the service. Three years later, the peacetime routine of drill nights and occasional musketry practice was about to be interrupted by the war in South Africa. The Boer War was not popular with Irish nationalists, who set about voicing their support for the Boers and discouraging recruitment for the British army. In Dublin, 1,500 posters adorned lampposts and billboards proclaiming, ‘Enlisting in the English Army is Treason to Ireland’.70 Nationalist Ireland was in the grip of ‘Boer fever’ and the Irish Transvaal Committee was formed in Dublin where prominent figures such as Ireland’s own Joan of Arc, Maud Gonne (actress, activist and soldier’s daughter), the poet W.B. Yeats, founder of Sinn Fein Arthur Griffith, and James Connolly, a revolutionary socialist and former soldier.71 Pro-Boer sympathisers were delighted to receive the news of the British army’s ‘Black week’, when the Boers achieved success in a series of battles at Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso. British losses increased the demand for replacements to bring regiments up to strength and the 5th (Irish) Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment were asked to supply a service company to reinforce the 1st Battalion of the Royal Irish Regiment in South Africa.72

On 20 January 1900, the men who had volunteered for South Africa attended a farewell banquet hosted by the Lord Mayor at the Town Hall.73 Two days later the company mustered and paraded to Lime Street accompanied by their band. Cheering crowds lined the streets waving green handkerchiefs, and green flags and banners flew from houses. The parade’s progress was hampered by the crowds and ‘Women relatives of the men forced their way into the ranks and proudly marched alongside their sons, brothers, or sweethearts’.74 At Lime Street the band played popular songs, including; The Girl I Left Behind Me, Steer My Bark to Erin’s Isle, as well as the ‘inspiring’ St Patrick’s Day and Garryowen. The men entrained for Warrington for four months’ training after which they departed from Southampton on board the SS Gascon on 17 February.75 Liverpool’s Celtic purists and pro-Boer sympathisers despaired at the spectacle of their countrymen’s neglect of ‘Ireland and Irish ideals’ by allowing themselves to be influenced by ‘Saxon ways’ and jingoistic khaki fever.76 The Liverpool Celtic Literary Society, rather than politicians, took the lead in voicing the city’s Irish nationalist dismay against the Anglicisation of the Irish in Liverpool. In line with their nationalist counterparts in Ireland, many of Liverpool’s Irish nationalist councillors supported the Boers; however, their support was largely muted. More overt expressions of nationalist pro-Boer sentiments in Liverpool came from the Liverpool Irish Transvaal Committee who provided a green silk flag adorned with a golden harp, bearing the words ‘God bless the South African Republics’; ‘From the Irishmen of Liverpool to the Transvaal Irish Brigade’.77

The 5th (Irish) returned home in November 1900 to a tumultuous welcome from the people of Liverpool. Thousands lined the footpaths to watch the 5th Irish marching past, while flags, banners and streamers were hung from buildings.78 By volunteering to serve in a foreign war the battalion ensured that the status of the Irish within Liverpool would rise. The Mercury led the praise, seizing the opportunity to take a swipe at those politicians who had previously questioned the loyalty of the Irish in the city:

Such a spectacle as that which was witnessed in Liverpool yesterday afternoon afforded another attestation of the communal feeling that surges up when the Empire needs and has the service of those who, by the wily tricks of passing politicians, are fraudulently suggested as its enemies.79

After receiving an official welcome home from the Lord Mayor at the Town Hall, the men were invited to a banquet at St George’s Hall where an Irish flag had been hoisted above the building.80 At the banquet, the Mayor praised the Special Service Company of the 5th Irish and outlined their exploits during their time in South Africa. He went on to mention that the company had endured offensive and defensive actions at Senegal and at Bethlehem, where Captain Warwick William and eight members of the company had been wounded.81 Highlighting their defence of the town of Belfast, the Mayor asked his audience, ‘What better place could an Irishman be in to defend? (Laughter and applause)’.

The Boer War had exposed tactical and manpower difficulties within the British army. Senior British military figures looked enviously and warily across the Channel at the large conscript armies of continental Europe and began a debate on National Service. In 1902, the National Service League was established to educate the nation to appreciate military questions.82 In 1905, Lord Roberts, a Boer War hero, voiced the concerns of many Edwardian soldiers of the threat posed by Germany and the necessity for National Service. He was, however, also aware of the fact that conscription was contrary to British notions of consent and the volunteer spirit. The army reforms instigated by W.B. Haldane, Secretary of State for War, reorganised the Volunteer units into a second-line army to be known as the Territorial Force. Used primarily for home defence, Haldane’s reforms also included an Imperial Service Option, which meant that units could volunteer for foreign service in time of war.83 The organisational restructuring led to the renaming of the Liverpool Volunteer Battalions. The 5th (Irish) Battalion now became the 8th (Irish) Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment. The battalion would form part of the Liverpool Infantry Brigade of the West Lancashire Division of the Territorial Force. The division was organised and administered by the West Lancashire Territorial Association, and Lord Derby, a local aristocrat and future Minister for War, became its chairman.84 Apart from the change in their title, nothing else was altered by Haldane’s reforms. In 1912, Haldane visited the battalion in Liverpool to open their new drill hall in Shaw Street.

LIVERPOOL 1914: DIVISION, RECRUITMENT AND UNITY

While some in Britain retained a healthy suspicion of German intentions in the years leading up to 1914, Germanophobia had become less obvious. World politics, including events leading up to the crisis in the Balkans in the summer of 1914, certainly featured in the British press, but were much overshadowed by the Home Rule crisis and the possibility of civil war in Ireland.1 The political and sectarian tensions surrounding the Home Rule crisis in Ireland were easily transported across the Irish Sea where they resonated, and were readily cultivated within the fertile Irish enclaves of Glasgow and Liverpool.

In the years leading to the introduction of the Third Home Rule Bill, a trio of nationalist grandees, John Redmond, John Dillon and T.P. O’Connor, visited various nationalist enclaves throughout Britain preaching to the converted and extolling the virtues of Home Rule.2 In Liverpool, the Orange and Tory faithful were praised and flattered by the fiery anti-Home Rule rhetoric of Archibald Salvidge, Sir Edward Carson and his ‘galloper’, F.E. Smith, the MP for Walton. If required, Pastor George Wise, the ultra-Protestant and anti-Romanist cleric, could be relied upon to inflame an already volatile situation.3 When Sir Edward Carson visited Liverpool in September 1912, he was greeted by thousands of cheering anti-Home Rule sympathisers including members of the Liverpool Orange Order and bands playing patriotic airs.4 Archibald Salvidge, Tory ‘boss’ and chairman of the Liverpool Workingmen’s Conservative Association, was the principle organiser for Carson’s visit, and accompanied the unionist leader throughout his stay in the city.5 The following day, he addressed a crowd estimated at 100,000 which had gathered to hear him speak at Sheil Park in the city. The event received national coverage and The Times described the scenes as ‘the orderly brigades of working men’ arrived at Sheil Park to the strains of The Red, White and Blue and Derry’s Walls along with other loyalist favourites of the day.6 Acknowledging the support of the Liverpool loyalists, Carson told them, ‘if there is to be a row I’d like to be in it with the Belfast men, and I’d like to have you with them. And I will (loud cheers)’.7 Shortly afterwards, F.E. Smith took to the podium where he made an extraordinary claim. Smith informed the audience that he had been speaking to three important ship owners in the city who had promised him that in the event of violence erupting between nationalist and unionists in Ulster, that they had agreed to supply ships to transport 10,000 Liverpool men across the Irish Sea to help their unionist allies.8 Carson was unable to attend Pastor George Wise’s lecture on ‘The Covenant’ held at the Protestant Reformers’ Memorial Church; however, he did send his apologies. In any event, several senior unionist notables including Col. Kyffin Taylor, MP for Kirkdale, and Lord Templeton, an Irish landowner, managed to attend where they heard Wise’s ‘characteristic’ address on the Ulster Covenant.9 Wise pledged his support for the unionist cause assuring his audience that by ‘relying on the God of their fathers, the God of Luther, John Knox, Ridley and Latimer’ that they would never surrender to Home Rule. In a somewhat optimistic yet witty conclusion, Wise stated that when Home Rule was dead, he might be asked to officiate at the funeral.

The crisis surrounding the Home Rule Bill did not die; on the contrary, in the two years preceding the outbreak of war in 1914, Ireland witnessed what David Fitzpatrick described as ‘an extraordinary outburst of mimetic militarism’.10 In 1913, unionist determination to resist the implementation of Home Rule in Ulster led to the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).11 After initially dismissing Carson’s bellicose rhetoric as mere ‘bluster’ and pouring ridicule on the UVF, Irish nationalists responded by raising their own organisation and the inaugural meeting of the Irish National Volunteers (INV) was held at the Rotunda in Dublin on 25 November 1913.12 Around the same time, Frank Thornton, a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), became a founder member of the Irish Volunteers in Liverpool.13 Thornton stated that the movement in Liverpool had its origins at a meeting at St Martin’s Hall in the city and that members of the IRB used their influence to urge members of the United Irish League (UIL) and the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) to enlist. The Liverpool contingent grew to a membership of 1,200 and later paraded at Greenwich Park near Aintree racecourse.

The seemingly imminent achievement of Home Rule gave the Irish inhabitants of Liverpool cause to celebrate St Patrick’s Day in 1914 with additional enthusiasm and patriotic fervour. Lorcan Sherlock, Lord Mayor of Dublin, was the honoured guest at a banquet held by Liverpool nationalists to celebrate their national Saint. T.P. O’Connor, who was unable to attend having been summoned to Westminster by the Whip, sent a letter which was read to the guests by Austin Harford: ‘I would have been glad of the opportunity of giving to my countrymen the most joyous message it was ever my privilege to deliver. Home Rule is won.’14 A few days later, O’Connor managed to visit Liverpool where he attended a demonstration organised in his honour. The nationalist and Catholic press, including the Freeman’s Journal and the Liverpool Catholic Herald, produced lengthy accounts of the parade which was estimated to have stretched for five miles as it made its way through the nationalist streets of Scotland Road, Kirkdale and Exchange districts in the north of the city.15 Participants in the parade included several Catholic confraternities, including the Irish National Foresters, the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Gaelic Athletic League. The Freeman’s Journal was keen to reveal that the parade also included many Irishmen who had served in the army and that ‘a body of three thousand men who were observed by everybody for the regularity of their marching and their military bearing’.16

The militaristic posturing of the Irish and Ulster Volunteers persisted throughout the first seven months of 1914 on both sides of the Irish Sea. Sympathetic editors of nationalist and unionist papers in Belfast, Dublin and Liverpool regaled their respective readerships with boastful accounts of men of ‘military bearing’ drilling and marching in Liverpool. The unionist Belfast Weekly News kept its readership informed of the development of the Ulster Volunteers in Liverpool.17 A ‘representative’ acting on behalf of the paper reported that Liverpool claimed to have ‘upwards of 15,000 Ulster Volunteers’ and that they were ‘fully determined to take an active part in any serious troubles that might ensue in Ulster’. According to the report, the Liverpool UVF comprised two sections which were split between Liverpool and Birkenhead. Led by a retired general ‘who was also an MP’, the reporter emphasised that the men were armed and well drilled. During his research on the UVF, Timothy Bowman asserts that membership of the UVF was largely connected with the British League for the Support of Ulster and the Union and that the UVF hierarchy in Belfast were reluctant to accept semi-trained or untrained and unarmed men into their ranks.18 Conversely, it seems that the contribution made by the Irish National Volunteers in the Liverpool was accepted by the leadership. The Liverpool INV attended drill sessions at various locations throughout the city including the Foresters Hall in Seaforth, Bootle Gaelic League Club and the Catholic Defence Association in Burlington Street.19

Unionist determination to resist Home Rule manifested itself the following month at Larne where the UVF landed a consignment of 25,000 rifles and 3 million rounds of ammunition.20 In late July 1914, the police in Liverpool raided a building close to the Exchange area in the city where they seized a considerable quantity of arms. The weapons were taken to Dale Street police station and officers from the Royal Irish Constabulary stationed in Liverpool were summoned to examine the weapons. The Liverpool Echo was unable to state whether the rifles were intended for the INV or the UVF ‘as the authorities preserve much reticence over the affair’.21

The expansion of civilian armies in Ireland during 1914 did much to enhance the bank balances of private arms dealers in Germany and Belgium. They must have been delighted when Professor Tom Kettle, barrister, poet and former MP, accompanied by John O’Connor MP arrived in Belgium to purchase rifles for the INV. The dealers were to enjoy an additional bonus. Unknown to Kettle and O’Connor, Sir Roger Casement had dispatched another group of men on a similar mission. Casement’s group succeeded in purchasing 1,100 rifles and had landed them by means of a private yacht at Howth on 26 July 1914.22 Unlike the UVF night-time operation to unload and disperse their haul of firearms, the INV landing was completed in daylight. As the volunteers made their way back to Dublin, they were confronted by police and later by a company of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers. The volunteers refused to surrender their rifles and after a few scuffles the volunteers managed to dispose of the rifles. As the Scottish Borderers were returning to the centre of Dublin, they were confronted by a hostile crowd which pelted them with stones and missiles. Without receiving any further orders, the soldiers loaded their weapons and fired on the crowd, killing three people and wounding more than thirty others.23

The incident caused great indignation among nationalists in Ireland and Britain, not least due to the disparity in the British government’s attitude towards the UVF and the INV.24 At the end of July 1914, Austin Harford chaired a meeting of the United Irish Societies of Liverpool where the shootings were discussed. The decision was taken to send a telegram offering their sympathies and pledging their support to the Lord Mayor of Dublin:

The United Irish Societies, Liverpool and District, meeting last night, asked me to express their abhorrence of the cowardly and savage attack on defenceless Dublin citizens, and to tender deepest sympathy with the relatives. And we assure our fellow-countrymen that 100,00 Liverpool Nationalists stand staunch with them in their fight to sweep murderous Dublin Castle completely away.25

Three days after the publication of Harford’s telegram, Britain declared war on Germany.

The declaration of war against Germany on 4 August 1914 did not inspire any jingoistic displays or anti-German excitement among the citizens of Liverpool. The Liverpool Courier reported ‘Large but sombre crowds in Liverpool’, adding that the usual Bank Holiday atmosphere was absent in the city and that this was ‘entirely due to the ominous and imminent possibility of this country being plunged into war’.26 Lime Street, however, remained a hub of activity where large crowds had gathered to await the return of the Liverpool Territorials from their camps, or to witness the departure of army and naval reservists to their regiments and ships. Pat O’Mara noticed a change in the slums of the north end of Liverpool, which went from being enveloped in ‘deadness and dullness’, to places of ‘lights and gaiety’. Scotland Road and the streets surrounding it were filled with ‘exceedingly happy soldiers, young and mature’.27 When his errands for Sneddon’s fishmongers led him to Lime Street or Bold Street, O’Mara stopped to watch the soldiers departing from the railway stations. ‘I would forget all about the fish and listen to the loudly blaring bands at the heads of the various contingents. There were all kinds of soldiers, with many of the faces well known to me and from my neighbourhood: Connaught Rangers, Scotch soldiers – very hilarious in their kilts, Liverpool’s own pride, the Eighth Irish, and many others all happy and in a distinctly holiday mood.’ A day later, the same paper bemoaned the fact that the Territorial Army required some 50,000 men and 5,000 officers to bring it up to strength.28 The paper urged men of military age to enlist, hinting that the war would bring unemployment and that the only way to avoid it was to serve with the colours. Additional military training for the Territorials would, the paper argued, ‘make them finer fighting material even than our regiments, certainly better than the machine-made fighting automatons of Germany.’ During the August Bank Holiday, men of the Liverpool Territorial Battalions had been attending a series of annual training camps. The Liverpool Irish along with the 5th and 7th Battalions of the King’s Liverpool Rifles had been based at Farleton, Westmoreland, while the Liverpool Scottish, the 9th Kings and the 4th and 5th South Lancashire Regiment were camped at nearby Hornby. Some men had anticipated being moved to Aldershot or some other military centre; however, they were surprised when the order came to strike their tents and they were told to return home and await further orders.29

During the first months of the war, Liverpool Irishmen were faced with the decision as to whether to make their way to the recruiting office or wait for guidance from their political and religious leaders. Confirmation that John Redmond had managed to deliver Home Rule came on 18 September 1914 when the Home Rule Act received Royal Assent. Redmond had already committed the INV to home defence during the war, but in an apparently extempore address at Woodenbridge, County Wicklow, on 20 September, he went further:

The war is undertaken in defence of the highest principles of religion and morality and right, and it would be a disgrace forever for our country, and a reproach to her manhood, and a denial of the lessons of her history, if young Ireland confined her efforts to remaining at home to defend the shores of Ireland from an unlikely invasion, and shrunk from the duty of proving on the field of battle that gallantry and courage which has distinguished our race all through its history. They should first make themselves efficient, and then acquit themselves as men, not only in Ireland itself, but wherever the firing line extended, in defence of right, freedom and religion in this war.30

Liverpool Irishmen who were regular soldiers or reservists were obliged to mobilise. Like every other territorial battalion, the Liverpool (Irish) Battalion of the King’s Liverpool Regiment complied with Haldane’s intention that the primary purpose of the Territorial Force was home defence.31 Territorial battalions could, of course, volunteer for foreign service, and every territorial battalion in Liverpool volunteered to serve abroad. Having volunteered, the Liverpool Irish began a recruiting drive to bring the battalion up to strength. In September 1914, recruiting adverts for the Liverpool Irish appeared in the local press: ‘This battalion has volunteered for foreign service and requires a few picked men to complete. Also, men for home defence battalion now forming.’32 The advert invited potential recruits to call at the battalion’s headquarters at 75 Shaw Street and carried the banner heading of ‘ERIN GO BRAGH’ (Ireland forever) ending with ‘GOD SAVE THE KING’. The phraseology of this appeal is noteworthy; it manages to assure prospective Irish recruits of the battalion’s ethnic origins and to reassure English recruits of its allegiance to the crown. Moreover, it informed the populace of Liverpool of the 8th (Irish) battalion’s commitment to the war effort as a fighting battalion as opposed to one on home service, thereby enhancing its reputation in the city. T.P. O’Connor telegraphed Colonel Myles Emmet Byrne, commanding the Liverpool Irish, congratulating him on his efforts and expressing his satisfaction at the numbers coming forward to enlist. ‘I am delighted to hear Irishmen are acting up to Mr Redmond’s manifesto and speeches by going to the front in defence of liberty, justice and the sacred principle of nationality and that they are joining distinctly Irish [sic] so once more an Irish Brigade may play an historic part in defending free Europe against a military despotism.’33

Just two days after Redmond’s Woodenbridge speech, T.P. O’Connor spoke at a mass recruiting meeting at the Tournament Hall in Liverpool where he shared the platform with another pro-Home Ruler and First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, and his old adversary and anti-Home Ruler, F.E. Smith.34 The Echo