45,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

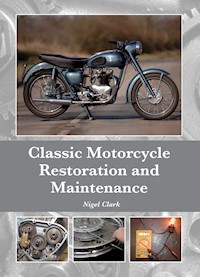

A complete workshop guide to restoring and maintaining your classic British motorcycle. Covering the principles of restoration and maintenance, and therefore applicable across all post-war classic British marques such as BSA, Matchless, Triumph, Norton, AJS and Royal Enfield, Classic Motorcycle Restoration and Maintenance covers everything from general maintenance procedures to full engine strips and rebuilds. With step-by-step instructions and over 800 images throughout, the book covers, amongst other things, buying guides, legislation, essential tools, workshop advice, safety stripping and rebuilding the key components for both singles and twins. The common parts manufacturers, such as Amal, Smiths and Lucas are covered too. With general maintenance, advice, recommended sources and additions included - this new book is an essential resource for the home classic restorer.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 619

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Classic Motorcycle Restoration and Maintenance

Nigel Clark

The Crowood Press

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Nigel Clark 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 882 0

Disclaimer

Safety is of the utmost importance in every aspect of an automotive workshop. The practical procedures and the tools and equipment used in automotive workshops are potentially dangerous. Tools should be used in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s recommended procedures and current health and safety regulations. The author and publisher cannot accept responsibility for any accident or injury caused by following the advice given in this book.

contents

acknowledgements

1

introduction

2

which classic?

3

getting started

4

stripping down

5

the chassis

6

the engine

7

transmission

8

the carburettor

9

ignition

10

the electrical system

11

the cycle parts

12

the big finish

13

clocks, dials and instruments

14

essential fluids

15

the paperwork

16

general maintenance

useful contacts

abbreviations and glossary

index

acknowledgements

This list is relatively short as most of the information in this book is based on experience gained over several years of restoring old British motorcycles of varying shapes and sizes. Of course, there is a great deal of technical detail of which I neither know nor deem necessary to know particularly deeply, as there are others who specialize in these fields and it is to them I turned for their advice and for that I express much gratitude. They have given freely of their immense skills and knowledge, and without their help I could not have completed the task of compilation and I thank them all.

Accreditation must go to the following for allowing use of their copyrighted documents:

Joachim Seifert of Norton Motors Group, for permission to use extracts and diagrams from various Norton documents; Colin McSeveny of Smiths Group, for permission to use extracts and diagrams from various Smiths Industries documents; Dave Bennett of BSA Company Ltd, for permission to use extracts and diagrams from various BSA documents; the University of Birmingham, for the archive images of the BSA factory; Lucas Electrical, for permission to use extracts and diagrams from various Lucas documents; and Triumph Motorcycles, for permission to use images from various brochures.

Special mention must go to Dave Flintoft, BSA Gold Star specialist, engineer par excellence and all round good egg, who spent far too many unprofitable hours demonstrating and advising me on various engineering tasks; the ever-pleasant Bob Wylde, for his time and patience with wheel building; Ferret, the electrical magician; Adrian Hill, of Morris Lubricants, for his advice on oils; Boyer Bransden, for their electronic ignitions; Jan de Jong at ABSAF; Kate Emery at Norvil Motorcycles; and Ben Coombes and the ace team at Amal and Burlen Fuel Systems. There are others too – my late pal Bob Byatt, for his saintly patience and ever willingness to help me out, sorely missed, and to Katapultgrafik for the artwork.

Thanks also must go to – in alphabetical order – Pete Adams, Paul Andrews, Neil Beadling, Steve Clark, Tony Pearson and Mike Powell.

1

introduction

Classic > adjective1 Judged over a period of time to be the highest quality. 2 Remarkably typical. Synonyms – adjective1 Definitive, enduring, exemplary, masterly, outstanding, archetypal, paradigmatic, quintessential. Noun1 Masterpiece, a work of art of established value.

The origin of the word, like much of our rich language, comes from the Latin classicus, meaning ‘belonging to a class or division’ and later ‘of the highest class’.

In the years since the Second World War the term has been used more loosely, initially to represent designs of outstanding merit, and latterly, more generally, to represent items which, to put it bluntly, are simply old.

It’s a term that is now widely open to interpretation. Taking aircraft as an example, it is surely fair to adorn the likes of the Supermarine Spitfire, Avro Lancaster and Vulcan, English Electric Lightning and others of similar ilk with the description. Likewise Sir Nigel Gresley’s fabulous, art deco Pacific Streamliner locomotives, or those wonderful coachbuilt beauties from Messrs Rolls Royce and Bentley, or George Brough’s hand-built specials, or Phil Vincent’s super-fast V-twins, or the all-conquering racing Nortons from Birmingham …

The list is probably endless and each has its own argument for and against. What about Honda’s little 50cc step-thru moped? ‘What about it?’, you may ask. It’s a throwaway utility vehicle of no particular value apart from a basic means of getting from place to place, particularly in less developed countries, where it is often used as family transport. Images are regularly seen of the poor little thing overloaded with husband, wife, several children, animals, bales of straw, boxes of fruit, you name it. So how then can it be a classic? Well, it’s been in production in various specifications and sizes for over half a century and has sold tens of millions of units and continues to do so to this day. In that case, the dictionary definition of ‘definitive’ and ‘enduring’ certainly applies, though to be fair the ‘Nifty Fifty’ is at the opposite end of the scale to the likes of the Velocette Venom Thruxton when it comes to desirability – and market value. Having said that, would a peasant farmer from the developing world swap his Honda for a Thruxton? Certainly not in the practicality stakes, as a Thruxton would be no use to him whatsoever; but then, in his situation there is no classic status, his bike is simply everyday transport – and that of course is what most of our so-called classics once were.

Nowadays, anything with any age to it is deemed classic. As the classic car market has seen the prices of exotica climb to extraordinary heights, so has that vacuum formed below it sucked up the prices of lesser, more run-of-the-mill vehicles. As said market shows no sign of diminishing and the banks’ interest rates continue to stagnate, the investors have realized that a good return can be had from the classic motorcycle. This has had two effects on the market. The first is that prices for machines with a genuine history and provenance have rocketed, which in turn has flushed out onto the market many machines that have been tucked away for years, as owners finally cash in.

Once upon a time a Coventry Eagle V-twin such as this was just an old motorcycle; now it’s a very expensive and very sought-after commodity.

Not many years ago, anyone who had an old motorcycle, or car come to that, was seen as being, shall we say, at worst not particularly well off, or at best some form of eccentric. However, many such people eventually had the last laugh, as the old rubbish they stored away in their sheds and hen huts steadily became valuable and sought-after machines. Those hoarders now have an extremely healthy pension pot!

A BRIEF HISTORY LESSON

The story of the fairly rapid implosion of the British motorcycle industry, followed not long afterwards by that of the car industry too, is well documented in many other books, and while today such industries are looked back upon through those familiar rose-tinted spectacles, hindsight now shows that the demise was without doubt inevitable – though it need not have been so.

As the men (and women of course) returned from the war and factories geared up for massive export production to try to pay off the crippling debts incurred, the attitude of the country’s workforce had changed. Having endured five years of conflict, followed by at least another five years of rationing and hardship, people wanted a better life, certainly better than that of the immediate pre-war years, and they were prepared to make a stand for it.

As far as the factory management was concerned, the easiest and most sensible way in which to get production into full swing was to give the pre-war designs a bit of a facelift and make as many as possible. Bear in mind of course that many factories, particularly the smaller ones, had ceased motorcycle production altogether to concentrate on the necessities of the war effort, making anything from aircraft parts to generators and ball bearings. So with the outbreak of peace, they had no new designs and even those lucky enough to have any tooling survive at all were left behind as the likes of Triumph had a head start. Many never reappeared at all.

The government had requisitioned all Triumph production to be for the military, but the original Coventry factory was bombed out in the devastating blitzkrieg raid of November 1940. As is (or at least was) the British way, with backs to the wall, a temporary factory was established in Warwick, tooling repaired and made good and production restarted in double quick time. Meanwhile, a new factory was built at Meriden, a village between Coventry and Birmingham, and one Edward Turner set about designing a twin-cylinder machine, which, once the war was over, would be ready to set new standards and leave the opposition floundering in Triumph’s wake. The other factories had to follow suit, though many soldiered on for a few more years with outdated designs, eventually shrinking away to nothing.

After the Second World War, people wanted some fun and the motorcycle was a perfect way to find it.

The Bracebridge Street Norton factory in Aston, Birmingham, immediately post-war.

Norton left their original home in the early 1960s but the facade has changed very little.

The actual Norton factory building was around the back on Aston Brooke Street. Sadly this iconic old building has gone, replaced by a sprawling mail sorting office.

The Meriden Triumph factory in its prime.

The pre-war Triumph Tiger 100, a breathtaking sports machine, within the financial reach of most and a standard by which all others would be judged. Its production was delayed by six years due to the onset of war in 1939.

As the austere 1950s turned into the swinging 1960s, industrial relations in general were deteriorating across industry as a whole. In the motorcycle industry problems were legion. As the Italians showed that their multi-cylinder machines were the future on the racetrack, outpacing the previously all-conquering British singles, the small, almost elite, band of designers, in particular Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele and their associated henchmen, were busy designing and building prototype machines, which could have easily taken on and beaten the world’s best and led to a range of road-going motorcycles of an advanced design and specification, the likes of which had never been seen before. However, that would have meant retooling for manufacture and development, which spelled expense to the company accountants and a loss of dividend to the shareholders, so inevitably, and no doubt immensely frustratingly for said designers, practically all such designs were vetoed in favour of simple updates to the existing machines – many of which, such as the Matchless G3 range, could be readily traced back to the despatch riders’ favourite machine of the Second World War.

To say most management in the motorcycle industry was complacent is an understatement. They had a strange belief that their machines’ shortcomings, oil leaks being a prime example, were quite acceptable to the customer, who liked nothing better on a Sunday but to repair, maintain and clean his machine in order that it would get him to work for the following six days. However, there was much more.

The factory buildings – Triumph excepted – were at best Victorian, the machine tools were equally as old and worn and the management was weak in the face of an increasingly militant workforce and powerful left-wing trade unions.

It’s an obvious scenario now. Post war, the Japanese and the Germans had to start from scratch, with a clean sheet of paper and a piece of land. As such, their factories were state of the art, as were their designs. Already several years old at the start of the war, and having run flat out during it, there was little hope of the weary old British factories being able to compete without the all too lacking enormous investment. While the defeated countries began with nothing to lose and everything to gain, our home industries struggled on to pay off the war debts mentioned previously – export or die, was the call.

Carefree summer days, fun and pretty girls at the seaside – or so the marketeers would have you believe.

With roots harking back to the DR’s favourite mount, the AJS and Matchless trials bikes of the 1950s and 1960s were first-class machines for the job.

There is a story that when Norton production was transferred from the hallowed ground of Bracebridge Street, Birmingham to AMC parent company headquarters, in Plumstead, London, in 1962, the machine operators there ruined a colossal amount of Dominator crankcases because the bearing holes didn’t line up. Eventually the old, retired, ex-Bracebridge Street machinist was contacted for his advice, to which he asked ‘Didn’t you take the plank?’, the folklore reckoning being that the boring machine was so worn that a piece of wood was wedged into place to keep it running true. Whether there’s any truth in the tale or not is really irrelevant – without doubt the Norton factory tooling was well past its sell-by date, and indicative of the industry as a whole.

Ignorance is bliss, and even as warnings were being voiced about the potential threat of the oriental machines, it was naively believed that they were only interested in small machines and the world would continue to buy big British bikes. As we all know now, by the time our factories woke up to the fact that the Japanese could build big, reliable bikes of a much higher specification and, most importantly, at a fairly competitive price, the writing was already on the wall. For sure, when the remains of the industry was lumped together into one company, they put up a fairly good rearguard action but the dogma of varying political factions ruined what chance that ever had.

CLASSIC ROOTS

Even as the factories returned to peace time output, there was a faction of motorcycle enthusiasts who felt it necessary to try and preserve the two-wheeled heritage of the early years. In April 1946 a meeting was held at the Lounge Cafe, Hog’s Back, near Guildford in Surrey, where thirty-eight enthusiasts gathered to discuss the forming of a club for owners of machines manufactured prior to December 1930. The Vintage Motor Cycle Club was born.

Over the years the club has seen myriad changes, but while keeping abreast of times and attitudes, it has remained more or less true to its roots, with a rolling twenty-five year eligibility date, which of course now entitles many Japanese machines to take part. This is a bone of contention with many, for as the once great names of the home industry all went to the wall in the face of the unrelenting onslaught from the land of the rising sun, those who lamented this loss circled their wagons and stood by their old bikes.

The view down Armoury Road in the 1960s – houses along one side, the mighty BSA factory on the other.

The front of the BSA factory did not go overboard with its advertising of Ariel.

BSA main gates. The concrete-framed building on the left (Truscon) and the single-storey section of traditional building beyond it are the only remnants of the once sprawling factory. The Truscon building is privately owned and in poor condition and subject to an ongoing effort to have it listed and restored. The other buildings still house the successful BSA guns company. All the other magnificent old buildings have long since gone to make way for faceless industrial units.

The racing section of the Vintage Motor Cycle Club threw a lifeline to those who still wanted to race on their old motorcycles.

Because the VMCC cut-off date for the racing section was, initially at least, 1958, owners of later race machines formed their own race club – the Classic Racing Motorcycle Club.

As the swinging sixties turned into the strife-torn seventies, it must be borne in mind that the cessation of world hostilities was still only a couple of decades past and for many, the atrocities of the Japanese during that conflict were still quite raw in the mindset of a generation. Understandably, there was much resentment. However, there was a new generation reaching motorcycling age who had been fortunate enough to be raised in an environment without world war or many of its repercussions, and most carried no such emotional baggage. The new Japanese machines were brightly coloured, stylish, reliable, fast and affordable and the youngsters hocked themselves up with years of monthly payments – and so it went on. The British motorcycle industry was dead and buried.

For over a decade the Japanese big four – Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki and Kawasaki – held sway but for those who took notice, it was plain to see that at grass roots level something was afoot.

For example, in those heady days of the 1960s, an ordinary national road race meeting – in which the country’s top privateers, on their Nortons, Matchless and AJS singles, and the sidecar crews with their BSA and Triumph outfits – would make up the programme, would often attract a crowd of perhaps 30,000 fans, while an international meeting, where the big prize money attracted the world champions, could see crowds of twice that. As the Japanese two-strokes steadily crept up the capacity classes – the 351cc over-bored Yamaha twin killed off the 500cc British singles, having already done away with them in the 350cc classes (even though it was invariably the same bike, capacity was rarely checked) – and the world champions stayed away, the crowds lost interest and attendances dropped hugely.

What had become of all those bikes, which were no longer competitive? Some were no doubt sold on for next to nothing while others were unceremoniously dumped into the back of the shed. Then someone had a bright idea. Why not start a club, a bit like the VMCC, but purely for race bikes, where these old bangers could compete again, against similar machines? Enter the Classic Racing Motorcycle Club.

This gave the bikes a new lease of life, encouraged more to join, attracted excellent crowds of like-minded enthusiasts and generally went from strength to strength.

As the modern motorcycle horsepower race grew out of hand during the 1980s and bikes became physically bigger, the enthusiasts of the earlier machines faced a problem: spares, or rather the lack of them. As former agencies of the British marques turned over to the Japanese, many cashed in on the scrap value of the parts held in stock in favour of the faster-selling contemporary machine parts, while others just boxed them away out of sight and out of mind, selling too few to warrant more attention. It became difficult for anyone running or restoring a post-war British bike to find good-quality spares, and practically impossible for owners of pre-war machines. To make matters worse, imported pattern parts began to flood the market and many were, to say the least, of dubious quality. They were ill fitting, incorrectly threaded, manufactured of the wrong material or not hardened so they wore out at an alarming rate, or worse, broke up and caused damage to other previously serviceable parts.

Something had to be done about it, and slowly but surely it was. If a part was needed and it was no longer available, or at least not to a satisfactory standard, the old adage ‘what man has made, man can make again’ came into play. Marque enthusiasts within owners clubs often found themselves not alone in needing a part or parts and invariably there would be a retired engineer within their ranks, or even a working or self-employed engineer who could undertake machining operations within his own time. He would be asked, or take it upon himself, to make a certain part and this inevitably led to others requesting his services. Then perhaps the owners club would put out the word that they had a batch of said parts available for sale to members, they would sell out and more would be ordered, along with further requests for different parts. From this, improvements were made, replica items in stainless steel instead of the original mild steel and so on, and as technology and materials improved, so did the quality of the replica parts.

Many has been the time that an engineer enthusiast found himself redundant and with nothing to lose, started up in business making specialist parts for certain machines. His business would increase as word spread and a wider range of parts became available, and from this perhaps the engineer would then digress into other marques. Another common story is that of the engineer who began producing parts for his own machines, followed by the same for his friends and colleagues and then the general public, until such time as his sideline was so big that he had to quit the day job to concentrate on his new business.

This new cottage industry blossomed and reputable businesses established themselves as manufacturers of top-quality replica parts, engine and gearbox parts, clutch parts, wheel rims, brake shoes and so on. The list grew in both number and complexity, with pressed steel cycle parts, cylinder barrels and heads, carburettors, electrical systems, crank and gearbox cases being added, until eventually it became possible to build a complete machine entirely from newly manufactured spare parts. Who would have ever imagined in the early 1980s, when enthusiasts were struggling to extend the life of their weary and obsolete old Amal carburettor by boring out the body and sleeving the throttle slide, that twenty years hence it would be possible to buy any of Amal’s excellent range of motorcycle carburettors off the shelf; or that brand new Manx Nortons could be had from no fewer than two manufacturers in England, one in Australia and engines from at least one other; or that BSA’s Gold Star or Matchless’s G85 engines could be bought new, likewise Weslake’s fourvalve twin, or a complete new Norton Commando, Dominator or Vincent Black Shadow – or, to put the icing on the cake, a Brough Superior …

Brand new and readily available, Matchless G85 engines …

… and Gold Star BSA too.

Complete Norton Dominators can be built from new parts by Norvil Motorcycles.

… likewise Commandos in any style or era.

A brand-new Vincent Black Shadow, sir? No problem, that’ll be £a lot, please.

There were also a canny few who, when various former dealers were retiring, selling up, or simply changing allegiance, moved quickly to snap up any remaining genuine period stock – and what a terrific amount there was still out there. Add to this a whole host of specialist refurbishment services and it’s fair to say that the older motorcycle has never had it so good!

The demand for tricky-to-manufacture cycle parts, such as petrol tanks, oil tanks and toolboxes, has been met by a legion of pretty skilled tin bashers across India. A few years ago it was accepted that such items, particularly replica mudguards, would probably need varying amounts of work to make them fit correctly. This is not so much the case any more as the craftsmanship has increased dramatically, with many parts being as good, if not better, than original, and by virtue of the labour situation in their place of origin, prices can be very competitive.

THE RIGHT TIME

Sadly, long gone is the time when a basket case, middleweight BSA, for example, would set you back ten or fifteen pounds: you would need to add a couple of zeros onto those figures now. As mentioned previously, as the topend machines such as the Broughs, Coventry Eagles, McEvoys, Vincents and so on have climbed to unbelievable values in the market, they have brought up in their wake, more everyday machines – which will form the basis of this publication – and there seems to be no end in sight. That’s no slight on more humble machinery; quite the contrary – there can be as much fun and enjoyment in restoring and riding an everyday classic as an exotic, and spares are easier to come by too.

Small-capacity machines, originally designed as commuters, or basic machines with which the factory could woo youngsters in an effort to steer their product loyalty toward bigger machines once they had passed their test, have found favour in the offroad competition sphere. BSA’s 250cc C15 and its bigger brother, the 350cc B40 – both essentially derived from the smaller sibling, Triumph’s Tiger Cub – can be converted into highly competitive trials bikes, along with Royal Enfield, Ariel, AJS and Matchless heavyweights, not to mention the plethora of regular lightweight names powered by the proprietary Villiers engine. Once considered unsuitable, now even the BSA Bantam is becoming a pre-65 trials force to be reckoned with.

This diversification has spawned a spares and service industry all of its own, with several trials specialists offering all manner of parts from a spark plug to a complete rolling chassis.

Akin to the days when ‘racing improved the breed’, all these developments can be successfully transposed onto everyday classics to improve starting, stopping and overall reliability. This in turn brings more older motorcycles back onto the road, and the more they are used the more parts they need so the whole process just gathers momentum.

SO WHY A CLASSIC?

There are so many reasons why a classic motorcycle is a good idea. First and foremost is the F word – Fun. Now, it may be exhilarating to travel at twice the legal limit in a straight line or experience acceleration that will slick tyres and ruin chains within hundreds rather than thousands of miles, but the former is strictly illegal on the Queen’s highways and the latter is extremely expensive. What’s more, once the initial buzz has worn off, it all becomes a little boring.

Modern motorcycles, without doubt, are sensational. High-tech and practically faultless in all that they do, they have reached a stage nowadays where they are indeed so good that their clinical excellence can become simply dull. That is something that can never be said of a classic. As realization of this dawns on more and more former riders of modern machinery, they now turn to a more sedate but equally fulfilling classic.

Character is a difficult thing to pigeon-hole. Is it the sound of a classic? Is it the timeless styling? Note how modern manufacturers have lately begun to introduce traditionally styled machines into their range again as the vast majority of buyers turn away from the race replica, so long beloved in the UK. Is it the fact that in comparison to the modern machine, the average classic neither goes, stops or handles as well? Is it because they vibrate more? Is it because they were essentially made and hand built by human beings instead of computerized machines and robots? It’s impossible to say, except that it’s probably a combination of all these things and more, because two seemingly identical machines will have distinctly different characters and idiosyncrasies. Like the proverbial Friday afternoon car, some classics will be better than others, yet they will be made up of the same parts and assembled in the same manner. One thing is guaranteed, however: they’ll both form a relationship with the owner. There will be times of overwhelming joy, grin-inducing fun, hammer-wielding frustration and head-in-hands despair, but the beauty of it all is that whatever problem arises, it can generally be fixed in your own workshop. You can be back on the road in double quick time, the bad times forgotten.

Classic ownership can bring about some strange encounters. Park your old motorcycle on the market square, in the car park, outside the supermarket, at the filling station, and on your return you will find someone standing by it who will want to talk to you about it – anyone from the glassy-eyed old chap who used to run one just like it when he was younger, to the BMX-mounted kid who loves bikes but has never heard of the make that the badge on your fuel tank so proudly boasts. They’ll want to see you start it – a fingers-crossed time for a first kick effort, the audience-induced poor start can be most embarrassing – and listen to it as you ride away, all the while ignoring the gleaming superbike next to it. Such simple things can be enormously satisfying and you know that they’ll be telling their friends about that lovely old Norton, or BSA, or Triumph or whatever they saw.

The unusual sound of a passing classic, compared to the commonplace howl of the modern 4-cylinder machine, will stop people in their tracks, have them stare and stick up a thumb or simply grin inanely.

Another positive incentive for choosing and old motorbike is economics, for most classics are tax exempt. Based on the age of the vehicle – four-wheelers are included too – and the presumption of limited mileage, a rolling twenty-five-year exemption, applicable to any vehicle, was introduced by the Conservative government but in 1997; when the Labour party took over, they put the brakes on the rolling system and applied a cut-off date of 1 January 1973. Understandably this proved unpopular: for example, if your machine was built on 31 December 1972 and your mate’s was built two days later, he’d pay full tax while you wouldn’t pay any. In 2104 the rolling system was reinstated, but now only for vehicles forty years old or more.

You’ll always find nice bikes and interesting people to talk to at any classic or vintage gathering.

There’s no better way to blow away the winter cobwebs than a ride out on your favourite classic.

What’s more, in a rare moment of inspired thinking, the Conservative/Lib-Dem coalition government of 2012 decided that, seeing as the vast majority of classic owners cosseted and maintained their vehicles to a high standard, it was unnecessary for them to have to try to get their classics to conform to the ever-increasing standards of the modern day MoT test. Since November 2012, all vehicles built or registered prior to 1 January 1960 no longer have to undergo a mandatory MoT test, though it remains optional should the owner feel so minded.

So, now you’ve no MoT to pay for, as well as no tax – but what about insurance? Well, that’s another bonus, because many insurance brokers realize that classic owners not only look after their machines extremely well, but they also respect their bikes’ age and ride them accordingly, thus not being the high-speed risk of the modern superbike. Generally speaking, classics don’t come out during the bad weather months, so the only real risk to consider is that of theft. As such, there are several specialist insurers who have excellent packages available to the classic owner, with agreed value, limited mileage and a variety of other inducements, which can make comprehensive insurance very reasonable indeed. What’s more, multi-bike cover can be cheap, because, after all, it’s only possible to ride one bike at once.

Another thing to bear in mind is component life. For drive chains and tyres this can be measured in years rather than miles, fuel consumption is invariably excellent and the simplicity of home maintenance keeps running costs to a bare minimum. There’s never been a better time to own a classic, so what are you waiting for?

With a middleweight classic and some nice weather, there’s nothing finer than exploring the country lanes at a steady pace.

Park up your classic and watch people ignore the modern bikes to come and look at yours.

Triumph was the last of the British mainstream motorcycles to fall.

2

which classic?

How long is a piece of string? Your choice of classic depends on any number of things – your engineering and mechanical skills, self-confidence, available space, security, tools and of course the size of your wallet.

Common sense must prevail: while the initial enthusiasm to set about your project will be all-consuming, if it’s, say, in a lock-up garage half a mile or more from your eighth-floor flat, a cold, wet and windy evening after a day’s work will soon temper that enthusiasm and before long your classic will be advertised on ebay as an unfinished project and without doubt you will finish up out of pocket.

Also think about your future plan for the classic. Once you’ve restored it and it’s running well, are you going to keep it for years or do you fancy selling it and getting another different project? Bear in mind that it costs almost as much to restore a small bike as it does a big one but the returns are much less, as per Ford’s old adage ‘big car, big profit, small car, small profit.’

If it’s your first restoration, then avoid the temptation to buy a basket case, that is, a bike that has been completely dismantled, because no matter how much the owner insists that all parts are present and correct, you can bet your life, there will be something missing. It might be, indeed it probably will be, only a small component part, but sod’s law dictates that the part gone awol will be critical to the assembly of a whole load of others. Likewise, unless you are an experienced restorer or you are intending to build up a classic without particular reference to its original specification, avoid the loosely assembled machine with obvious parts missing, as this will prove to be an expensive exercise in parts gathering – unless of course, it’s such a bargain price that it would be foolish to ignore it.

Having said that though, endless hours trawling through boxes at various autojumbles – if you can justify the extortionate and ever-increasing gate prices of the major shows and events – can be both great fun and incredibly frustrating at the same time, but enormously satisfying if the sought-after part eventually turns up. Even after all these years, parts do still keep turning up but you’ll stand just as good a chance of finding what you need on ebay. Often you can spot a part for your machine and discover that the seller has many other parts for sale too; in such a case it’s always worth contacting him to see if he has the very part you need.

If you can, find a complete machine. Don’t worry too much if it’s rusty, oily, or even that it doesn’t run, just make sure that it’s pretty much in one piece. It may be that it’s simply been stored up for years in less than ideal conditions and the damp has affected the electrical system or the ignition, or of course it may be that it’s worn out or broken somewhere inside, but providing the kick start will turn over the engine it’s a good enough place to start. If it doesn’t, then at least there is an element of leverage with regard to the bartering process, especially if the seller also doesn’t know quite why it’s seized. The overall acceptable standard of decay is relative to each individual so making the final decision on whether or not the project is too far gone, too much like hard work, too expensive for what it is or simply too daunting is down to you.

The seller will say it’s all there but you can bet your life it won’t be.

An incomplete project such as this BSA B33 is not too bad a start because most of the missing parts are available as pattern replicas – the important parts are all present.

Naturally, the best buy is one that is a runner but probably needs work to make it either reliable or more aesthetically pleasing. Surface rust on wheel rims and bright works is not detrimental to anything other than the look of the bike; likewise oil leaks are not a problem except again to the appearance of the bike, the state of your riding gear and the place where you park the bike. All these aspects can be greatly improved if not entirely cured.

So where do you start? Well, with all the previous preliminaries taken care of, it’s a case of practicalities. Choose a mainstream marque for which parts are interchangeable across a variety of ranges. Take BSA, for example, the Small Heath, Birmingham concern was once the biggest motorcycle manufacturer in the world, with one in four machines being a BSA, so there were many made and many still around. During a set period, say between 1958 and 1961 as a snapshot, the twin-cylinder range shared cycle parts, suspension, brakes, electrics, even the gearbox with the single-cylinder range, and the frames were practically the same too, so a mudguard or an oil tank from a single will fit a twin as it is the same part. The only difference is the colour scheme.

This greatly eases the search for parts. Leaving only the engine as the individual aspect, even then most parts are interchangeable between the 350cc and the 500cc singles, and the 500cc and 650cc twins. What’s more, the great number of these machines still being used on the road has resulted in most parts becoming available again as newly manufactured and on the shelf. This applies equally, of course, to the likes of Triumph, Norton, Royal Enfield and most other major marques.

Amazingly enough this Thunderbird was a pretty good runner, though later investigation showed a blocked sludge trap and a plethora of rotten metal.

At one time, one in four motorcycles throughout the world was aBSA.

Velocette owners are a passionate bunch: once a Velo man, always a Velo man.

Velocette were renowned for their quality engineering and the marque has a very loyal and passionate following, but they do have one or two unusual design features, the clutch and primary drive arrangement being the most obvious. The clutch itself, and hence the primary drive system, is positioned in between the crankcases and the outboard drive sprocket. Whilst this makes changing the gearing with the sprocket an easy operation, to actually reach the clutch is more difficult. What’s more, because of its position within the limited space, it is a very narrow clutch with a unique scissor-type operating mechanism, which can be tricky to set up correctly. Indeed the factory service book states ‘Before attempting any adjustment of the clutch it is important that the operation of the clutch is fully understood …’

A situation where you have to remove a pressed steel cover to reveal the gearbox sprocket and then secure a steel peg through one of three holes in its centre, then locate it into one of the castellations in the shock absorber spring behind it and then rock the rear wheel backwards or forwards, depending on whether the clutch is slipping or dragging, calls for a bit of considered thought and no little concentration. If that does not do the trick, there are three pages of optional treatments in the manual … The Velocette clutch is not a strong assembly and will not stand a lot of abuse, but when set up perfectly and used correctly it is a very light and sweet unit. Superb machines the Velocettes undoubtedly are, but perhaps not the ideal choice for the first-time restorer.

Consider a few other more obvious aspects of classic ownership too, some of which will have a bearing on the restoration and maintenance costs. A twin cylinder engine, for example, obviously has, in some areas, twice the component parts of a single. Two exhaust pipes and two silencers instead of one, two con rods and two pistons instead of one, four valves, rocker arms and cam followers instead of just two, often two carburettors and so on.

Unit or pre-unit? In other words does the engine have the gearbox in with it, or does it have a separate gearbox? Does the idea of having to dismantle the gearbox together with the engine fill you with dread, because of course the gearbox can be treated as a completely separate entity in a pre-unit system. With a pre-unit system, the engine can be restored and put to one side before tackling the gearbox, or the other way round; and if the frame or rolling chassis is already prepared then the gearbox can be fitted into the frame to await its engine. The main advantage of the unit engine is that the primary drive chain runs between constant fixed centres, any slack or wear being taken up by means of a chain tensioner, and it’s generally easier to keep clean, whereas the separate gearbox has to be physically moved back and forth to adjust primary chain tension and it’s sometimes quite awkward to keep the area between the back of the engine and the front of the gearbox clean. In the latter case, there is also the issue of maintaining an oil-tight seal between the gearbox shaft and the inner primary drive case, because the case has to be slotted to allow adjustment movement of the gearbox, whereas this does not apply in the unit engine.

Triumph’s Bonneville, the epitome of the British twin.

BSA’s much-loved A7/A10 range with the separate gearbox was superseded by the not so popular unit-construction A50/A65.

The A50 and A65 engine was dubbed the ‘Power Egg’ for obvious reasons.

Then there is the frame – rigid, plunger or swinging arm. Of the three, arguably the first and last are the best bets. The rigid is straightforward with no suspension parts to have to consider other than a well-sprung saddle; and the swinging arm, which is removable from the mainframe, is supported on simple tubular bushes with a couple of sprung dampers. It’s relatively easy to remove and refit, along with readily available new bushes and so on, but there is the potential cost of new dampers, whereas with a rigid frame all that needs to be considered is the paint finish. The plunger system was an attempt to introduce an element of suspension by allowing wheel movement within an adapted rigid frame. It’s a system accommodated within a limited, closed ends space, and is accordingly not the easiest arrangement to work on; even when in good condition, it leaves much to be desired when compared to the systems that came before and after. Triumph’s sprung hub works on the same principle but in an even more complicated manner, as the plunger arrangement is built into a huge rear-wheel hub, rather than the frame itself – thus giving the rigid frame an extended lease of life.

KNOW THY BEAST

Before you take the plunge on the bike you fancy, read up about it as much as you can, buy or borrow books on the marque and model and learn the basic differences between the year ranges. A classic example is the BSA heavyweight range of 1956 and 1957, which used Ariel full-width all-alloy hubs in their wheels. This was essentially because BSA, as Ariel’s parent company, wanted to use up most of Ariel’s four-stroke range component parts, as the direction they were sending their subsidiary was down the twostroke road with the Leader and Arrow. A year before the change, BSA used single-sided hubs and in 1958 went onto full-width steel hubs.

Take a trip to a classic gathering such as Founder’s Day, the VMCC’s annual premier one-day gathering, invariably at Stanford Hall, near Lutterworth in Leicestershire, take photographs of similar machines and see what other owners have done to theirs. Better still, talk to the owner if you can find him, take his number and don’t be afraid to call him and ask his advice if you get stuck – most classic owners are only too pleased to help others, even if it’s only by advice from personal experience.

Join the owners club. Not only do you get a monthly magazine full of information, technical advice, anecdotes and dates of gatherings, you may also find there is a local branch where you can go along and meet other owners and enthusiasts who will welcome you into their fold and help you with your rebuild. The owners clubs invariably have a spares scheme too, from where you can obtain good-quality remanufactured parts, or even new old stock components. Naturally there is also a for sale and wanted section, where club members advertise their surplus wares, and you will find that the specialist retailers are advertised within the pages of the journal too. Another facility offered by the owners club is a dating service. If your purchase has no documents with it – logbook, tax disc and so on – the frame number can be cross-referenced with the factory records to prove the date of manufacture. A dating certificate from the club will satisfy the DVLA and you will be able to gain an age-related number plate for your bike. These are registration numbers that were allocated en masse to areas where the take-up of newly registered vehicles was small, for example the remote corners of Scotland. As such there are still many registrations from the correct period that have never been issued and are still available, and they look far more in keeping with a classic than a rather obvious ‘Q’ plate. This applies also for 1960s and 1970s vehicles with a suffix letter.

All you need to know is available out there.

BSA used their subsidiary Ariel’s elegant full-width alloy hubs in 1956 and 1957.

BSA called time on the Ariel four-stroke and used up the available wheel hub stock on their own machines.

If there’s one thing you feel you’d like to know, just ask – most owners will be only too happy to talk to you about their bike.

The VMCC is an extremely useful club of which to be part. They too have branches – or as they’re called, ‘sections’ – country-wide and are behind many top-class classic events. Within their Burton upon Trent HQ they have a breathtaking library, full of books, documents, factory records, trophies, brochures, photographs and much more. As a member you are eligible to spend time in the library to research whatever you feel like researching and there’s a full-time staff always willing to help you. The VMCC also has an excellent monthly journal and there is a team of marque specialists, whose sole objective is to answer queries and put people right on various aspects of that particular company’s wares. Indeed, for the larger marques there are also subsection specialists, such as for twins, singles, lightweights, two-strokes and so on. Whilst the club has to be run at a profit, like any other business, its main agenda is to keep old motorcycles on the road and their profile high, so it will not rip you off for their services, unlike other well-known commercial archives.

Membership of the VMCC is practically obligatory with an old motorcycle.

The club also has an excellent and very comprehensive transfer service, from where the transfers can be purchased for your motorcycle’s correct year of manufacture.

Once you have built up a little knowledge about your subject, you’ll feel far more confident when you assess a machine with a view to buying and can spot obvious items that are incorrect, or purport to be something they are not. If you are still not too sure, then take someone with you who is more experienced in classic matters. Whilst the vast majority of classic owners and enthusiasts are perfectly honest, there are inevitably those who are, shall we say, economical with the truth and the last thing you want to be doing is paying well over the odds for what is essentially a wreck.

PRELIMINARY CHECKS

Assume you’ve made your choice and you’ve found a bike that, for all intents and purposes, is complete but not running. Ascertain the length of time it has been out of service, for if it has been standing still for several years, do not under any circumstances try to get it to start. There may be countless problems inside that have arisen simply due to its inactivity, which could result in further damage to what might otherwise be a fairly light rescue mission. Corrosion may have rusted the bore, the piston rings may be stuck in their grooves, or worse, stuck to the bore, in which case forced movement may break them and ruin a perfectly serviceable cylinder barrel. Likewise corrosion may have affected the bearings, the big ends, camshaft faces and other parts. What’s more, despite the sump perhaps being full of old, black oil, the residue from the combustion process within it may have wreaked havoc on every metal surface immersed therein.

In the case of twin-cylinder engine, there’s a good chance that the sludge trap will be full too. The sludge trap is a tube that runs through the centre of the crank where the heavyweight deposits – such as combustion by-products, carbon and so on – carried within the oil are collected. Eventually, this tube fills and becomes blocked, thus restricting oil flow to the big ends and resulting in expensive engine failure.

Of course, if it’s only been stood for a relatively short time and it turns over on depression of the kick start, then after a few preliminary checks it may be all right to see if it will fire up.

Putting it simply, if there’s fuel and oil present and a spark occurring at the right stage of the combustion process, then there’s no real reason for it not to fire. However, if the fuel has been in the tank for a long time, it may have ‘died’. Leaded fuel used to take on a distinct smell when it was past its best, not to mention a pretty murky colour. Modern unleaded fuel has a very short shelf life – if not in a sealed container, then it may be a matter of just months. It may look fine and smell fine, but will probably be useless when trying to fire up an engine. Furthermore, it may have left a residue in the carburettor on evaporation, restricting or, worse, bunging the jets up completely.

Let’s assume at this point that the bike has not been standing too long. Firstly, take the fuel pipes off the taps under the tank and drain off the old petrol and dispose of it in a responsible manner. Underneath the crankcases you will see a plate or a hexagon headed screw into the sump. Undo this and allow the old oil to drain off into a suitable receptacle and then temporarily tip it through a filter back into the tank – a fine, domestic, tea strainer-like sieve will be adequate. Do not run on this old oil for many minutes, only for long enough to see if the engine will run.

Remove the spark plug and clean it with a wire brush, check the contact on the end has a small gap between it and the central core point, fit it back into its holder on the end of the lead and lay it against the cases, cylinder head, barrel and so on.

Remove the ignition points cover and slowly turn over the engine and see if the contact breaker points open and close. While they’re at their open point, gently insert a sliver of fine emery paper and clean the mating faces of the points.

At this point, a swift swing on the kick start should induce the click of a spark at the plug. If so, replace the plug in the head, fit the lead and add some fuel to the tank. Let it fill the carburettor, flood the carburettor by means of the tickler button on the float chamber and with a bit of luck, after one or two kicks, the engine should start. Don’t rev the engine too hard but keep it running and have a look inside the oil tank, where you should eventually see a regular squirt from the return pipe just under the filler neck. That tells you that the oil pump is working. Don’t be alarmed if it takes a minute or two, it has to circulate right through the engine before it returns to the tank.

The sludge trap from a 1955 Triumph – sludge indeed.

Old petrol, particularly unleaded, can leave behind a residue capable of blocking the system.

Undo the sump plug.

Let all the oil that has gathered in the sump run out into your collecting vessel.

No matter how quick you are, the oil will be quicker and run over your fingers.

The sump plug may be covered in metallic particles, which will give a good indication of the engine oil condition. Clean the threads before replacing.

If the twin-cylinder engine has never been rebuilt, despite it appearing to be in good condition, can you afford to take the risk of running it as is, especially regarding the sludge trap? If you’ve a single, then you will not have this problem, as invariably the big end bearing arrangement is different. Remember the old adage ‘better safe than sorry’.

Now, without wishing to sound patronizing or condescending, all this assumes that the new owner is mechanically savvy enough to know what the above terms mean and where said items – points, plug lead, big ends and so on – are found. These items will be covered in more detail in later chapters.

Sometimes, like in the case of this Norton, the area around the sump plug is tight and needs a special spanner. In this case, simply grinding the edges off the hexagon of a box spanner is all that’s required.

Use your feeler gauges to get the correct spark plug gap.

Amal 276 carburettor. The tickler button can be seen on top of the float chamber.

It will take a minute or so for the oil to travel throughout the engine before returning to the tank.

Shelves are just so useful, but the more you have, the more you’ll find to fill them.

3

getting started

Setting out your workshop space is critical, but as mentioned earlier, this all depends on personal circumstances. Some may have a spacious workshop, others a domestic garage, and other still just a garden shed, so some of the following may not be applicable to everyone purely on the grounds of elbow room.

Obviously, the main thing to start with is a bench. Anything will do as long as it’s sturdy enough to take the weight of the engine and is at a comfortable working height. A purpose-built wooden bench permanently fixed to the wall is ideal, though angle iron or another such support system is perfectly fine. The top can be boarded with heavy duty ply, blockboard, softwood planks, MDF or similar – all are adequate, especially if topped with a sheet of white-faced hardboard. The latter not only gives a jointless surface, it also helps with light distribution and makes spotting wayward nuts and bolts easier. It’s also fairly oil-resistant and easy to clean down. Avoid chipboard, even the fine-density flooring grade, unless you’re intending to finish it with hardboard, because not only is it a difficult and not very secure material to screw into, by its very nature it is absorbent, and if left wet, will swell and break up.

There again, it’s not difficult to pick up a length of unwanted kitchen worktop, which is invariably chipboard based but will have an impervious surface finish and may have a posh rounded nose to it and a jazzy surface finish. It may seem an obvious thing to say, but ensure it’s level, front to back as well along its length, as there’s little more annoying than having things rolling about on the bench. Also, make sure it’s of a good working height that does not have you bending or stretching. If your kitchen worktop height suits you, base the height on that.

It’s always useful to have a shelf above your bench, so you can have important items readily to hand at all times without cluttering up bench space – for example, a battery charger, the leads of which can be lowered to a battery on the bench when required but rolled up out of the way when not. Likewise, you could have a mini radio system with its push buttons instantly accessible and cables running up the wall and across to wherever you position the speakers. It’s a good place also to store everyday items such as scissors, pencils, marker pens, tape measure and that all-important workshop manual. The shelf doesn’t have to be anything industrial, just a couple of domestic brackets and a length of suitable board.

The same applies elsewhere in the workshop: the more shelf space you have, the more you’ll find to fill it. Oils, greases and various lubricants, paints, cleaners, fuel additives, polishes, distilled water, boxes of nuts, bolts, screws, washers, bulbs, fuses – you name it, it will find its way onto the shelves.

A white-topped surface helps you spot things when they go missing and also helps with the light distribution.

A small shelf over the bench is ideal for the battery charger and radio.

The more light you have on the bench the better.

Once that’s set up to your satisfaction, make sure you have a light source directly over the bench, be it a fluorescent tube, an angle-poise type arrangement, a rack of spotlights or just an odd bulb or two. Make sure that when you’re standing over an item of work, the light does not cast the shadow of your head and shoulders onto it. There is nothing more frustrating than having to move to one side in order to be able to see what you need to see.

Also, make sure your bench is supplied by an adequate number of sockets. You may need to have, say, a battery charger, a drill and the grinder all available to you at one time, not to mention perhaps the radio or the fan heater. Extension leads are all well and good, but they do get in the way and are a tripping hazard.

It may seem obvious, but a clock is fairly important too, especially if you don’t wear a watch. Not only does it give you an indication of how long you’ve been in the workshop, but it also allows you to time tasks, for example in the course of preparation of a rust removal immersion or painting.