Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Formed in 1868, and already possessors of a proud history by the outbreak of the First World War, the men of the 9th (Glasgow Highland) Battalion, The Highland Light Infantry, were right at the heart of the cataclysmic events that unfolded between 1914 and 1918 on the Western Front. One of the first Territorial units to be rushed to France in 1914, they participated in almost all the major British battles, including the Somme in 1916 and Ypres in 1917. Altogether, around 4,500 men served with the Glasgow Highlanders in the First World War. The composition of the Glasgow Highlanders changed dramatically over five years of fighting, as the original Territorial members were replaced. Despite this change, the ethos of the battalion, built up over half a century of peace and many months of warfare, survived. Alec Weir has steeped himself in the proud history of the Glasgow Highlanders in the First World War. His accessible, informal style, employing many first hand accounts, and his rigorous research combine here to produce a fascinating and detailed account of how ordinary men from all walks of life confronted and mastered the hellish conditions of trench warfare.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 971

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

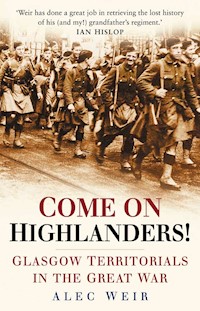

COME ONHIGHLANDERS!

COME ONHIGHLANDERS!

GLASGOW TERRITORIALSIN THE GREAT WAR

ALEC WEIR

First published in 2005This edition first published in 2009

The History PressThe Mill, Brimscombe PortStroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved© Alec Weir, 2005, 2009, 2013

The right of Alec Weir to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9588 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Preface

Introduction: Piecing it All Together

1.

Highland Origins

2.

1914: August to October – An End and a Beginning

3.

1914: November to December – Much-needed Reinforcements

4.

1915: January to March – Neuve-Chapelle – Nearly

5.

1915: April to June – Festubert

6.

1915: July to September – Loos

7.

1915: October to December – Second Winter

8.

1916: January to March – Lines of Communication

9.

1916: April to June – Lines of Communication then Back to the Trenches

10.

1916: July to September – The Somme

11.

1916: October to December – Still the Somme

12.

1917: January to March – Even More of the Somme

13.

1917: April to June – Arras

14.

1917: July to September – The Belgian Coast, then Ypres

15.

1917: October to December – Messines and Passchendaele

16.

1918: January to March – Still Passchendaele

17.

1918: April to June – Neuve-Eglise

18.

1918: July to September – The St-Quentin Canal

19.

1918: October to December – The Selle and the Sambre

20.

1919 – Guard Duties

21.

Retrospect

Sources and Bibliography

Appendix 1

Outline History of Glasgow Highlanders, 1868–1919

Appendix 2

Names of Those Known to Have Served with the Glasgow Highlanders in the First World War

PREFACE

The Glasgow Highlanders were right at the heart of the cataclysmic events that unfolded between 1914 and 1918 on the Western Front. They were one of the first Territorial units to be rushed to France when reinforcements were desperately needed in 1914. They continued there throughout the next three years of stalemate, participating in almost all of the major British battles – Festubert, Neuve-Chapelle and Loos in 1915, the Somme in 1916, Arras and Ypres in 1917. They were still there when, by March 1918, the Germans had at last defeated the Russians and were thus able to concentrate their full attention on the war in the west. The Glasgow Highlanders in fact played one of their most valuable roles of the entire war at this time. Finally, when the Germans began to crumble, the Glasgow Highlanders were right at the heart of the last big Allied push which drove the invaders back until they finally accepted defeat.

Like the apocryphal George Washington’s axe – two new heads and three new handles – the composition of the battalion at the end of the war was almost entirely different to that at the beginning. Most of the originals – Territorials – had gone even by the end of 1915. The volunteer replacements who joined during that year were also largely gone by the end of 1916. From 1917 onwards replacements were either conscripts or came from a variety of other regiments. But despite all these transformations the ethos of the battalion, built up over forty or so years pre-war, somehow survived, and the Glasgow Highlanders, as a battalion, marched away from the war with their heads held as high as when they went in.

They were a remarkable body of men. On the one hand they had the openness, straightforwardness and tremendous good humour that are typical of Glaswegians – but they also had the bottle. They were driven to be, and succeeded in being, formidable fighters, and the Germans quite rightly learned to fear them as ‘terrible Highlanders’.

INTRODUCTION PIECING IT ALL TOGETHER

A SIMPLE QUESTION – BUT NO REAL ANSWER

When I was born, the ‘Glasgow Highlander’ who had been the battalion’s Regimental Sergeant Major at the beginning of the war, and then later became their adjutant, was Major Frank Ernest Lewis MC DCM. To me though he was just ‘granddad’. By the time I wanted to know more about who he was and what he had done I knew perfectly well that he himself had not been around for quite a few years, but I was taken aback when the response to my simple question within the family: ‘What did granddad do in the Great War?’ got no further than an extremely vague: ‘Er, he was in the Scots Guards . . . I think . . . er wasn’t he?’

I was really stunned though when the answer to my next question, as to what had happened to all granddad’s papers, memorabilia, books and so on was: ‘All gone . . . he had that attic study at home full of things to do with the First World War . . . but after his death they were all thrown out.’ All trace of him seemed therefore to have disappeared, and besides this being a shock, what chance was there now of getting an answer to my question?

THEN A REVELATION

Not much, I thought, but then someone suggested writing to the army records office. It was something of a palaver to get the Ministry of Defence (MoD) application form completed in the right way, and I then had to wait six months to get a reply, but when it came there was a whole page and a half of information.

In particular it told me that my grandfather had been a regular, that he had enlisted as a private when he was not yet seventeen and then, in the middle of the First World War, been commissioned as an officer. His army career spanned nearly thirty years from 1900 to 1927, and while yes, up to 1917 he had indeed been in the Scots Guards, he was thereafter in the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) and then, postwar, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers.

What stood out though was that, although technically belonging to these other regiments, he had spent the entire period of the First World War attached to the 9th Battalion Highland Light Infantry, better known as the ‘Glasgow Highlanders’.

ANOTHER IMPASSE . . .

This surely gave me the solution. If I wanted to know more about what my grandfather had done in the Great War – and I did, because the information provided by the MoD had whetted my appetite – all I needed to do was get hold of a history of the Glasgow Highlanders? Unfortunately no, because I couldn’t find one. Initially I felt sure that I was just not looking in the right places, but eventually, after finding my way to the military history specialists, I was told that so far as they were aware no such thing as a published history of the Glasgow Highlanders had ever existed.

It seemed like another dead-end. Perhaps after all I would just have to be content with the information provided by the MoD?

. . . AND ANOTHER SHOCK

That might have been the case had it not been for someone in the family coming up with an obituary of my grandfather clipped from the Glasgow Herald. I’d already picked up from the MoD letter that he had been decorated with the Military Cross and Distinguished Conduct Medal and twice ‘mentioned in despatches’ which, in my ignorance at this stage, meant all too little to me; but I was particularly struck by how the newspaper referred to my grandfather’s ‘distinguished service’ and the description of him as ‘one of Scotland’s best-known soldiers’. Surely, as this obituary was as recent as the mid-1960s there must, somewhere, be more still to find out, even if not about him, then about the Glasgow Highlanders?

At least I could make a symbolic pilgrimage to his grave. I knew he’d been buried at Largs on the Ayrshire coast in Scotland because I’d been at his funeral, but not living in Scotland I wasn’t handy for a visit. Eventually though I made the journey, and the first part, finding the cemetery, wasn’t a problem. It’s on high ground overlooking the sea, and there are stunning views over the water to the Isles of Cumbrae in the near distance and Bute and Arran further away. But I couldn’t find his grave. I asked. The people there helpfully looked up the records and from this his plot was identified. But there was no marker, no stone. In this very large cemetery with countless tombstones, old and new, what was there to mark the last resting place of ‘one of Scotland’s best-known soldiers’? Absolutely nothing.

BUT THEN A BREAKTHROUGH – THE GLASGOW HIGHLANDERS’ WAR DIARY . . .

Granted, a gravestone is only a symbol, and many people these days don’t have one. Nevertheless the unmarked plot just seemed to underline how completely both he and the Glasgow Highlanders of 1914–18 had vanished without trace. Again though what could I do about it?

Try the National Archives, I was told. In the First World War all British battalions were required to keep a record of their daily activities and these should now be viewable at the Public Record Office at Kew. I’m not handy for that either, but in due course I made my way there, signed the necessary application forms and passed through the security barriers. Before getting to see any documents you have to find out their catalogue number, master the online application system and then wait for them to be retrieved from the vaults. In due course two cardboard boxes were handed over for viewing at a specially allocated seat in the reading room. And there it all was, the Glasgow Highlanders’ War Diary – hundreds of large loose-leaf sheets covered in scrawled handwriting. The sense of handling real original old documents is added to by the fact that your every move is watched by cameras and constantly patrolling security people.

An initial glance showed that entries for some dates were just a few words, while for others there were several pages. Typically, each day’s entry had a note of ‘place’ in the left margin, then the date and a description of what was going on. But there was so much of it. Even just reading through it would take far longer than one visit. True, it was possible to request photocopies, but only in small batches, and at significant expense, so this seemed impractical for such a mass of material.

Unexpectedly though, what appeared to be another major obstacle was resolved when I discovered that the Regimental Archives in Glasgow, now part of the Royal Highland Fusiliers, had a carbon copy. Moreover, they were willing to photocopy the whole lot for me – and at reasonable cost. This was a great breakthrough. But as it was still so hard to read, I decided to set about transcribing it.

. . . LOTS OF NAMES . . .

Long before that was all done I became aware of Soldiers Died in the Great War 1914–19. This mammoth directory, originally issued by HMSO in 1921, is still readily available in reprint in eighty volumes. Part sixty-three lists the dead of the Highland Light Infantry, battalion by battalion, and pages 37 to 49 deal with the Glasgow Highlanders. Even just a quick glance brings to light that no fewer than 1,200 of them died. But the list, in surname order, also gives first name, rank, serial number and date of death, together in most cases with supplementary information such as place of birth, place of enrolment and, where applicable, gallantry award and former unit.

From this, quite a lot can be deduced. Like the fact that only about 10 per cent of the fatalities occurred up to the end of 1915; that more than half of all deaths occurred on just seven fateful days, two in 1916, two in 1917, and three in 1918; that most of those who died in the early part of the war were Glasgow-born and Glasgow-enrolled, but that in the later years a considerable element were transferred into the Glasgow Highlanders from other regiments, some of which were not even Scottish. Oh yes, and that the first name of no less than one in three was either John, William or James – more or less equally, but in that order.

The next question was: What about officers? The answer, as might logically be expected, is a similar publication, Officers Died in the Great War 1914–1919, which, at pages 240 and 241, lists sixty-eight Glasgow Highlander officer deaths. In addition there is The Cross Of Sacrifice, Volume I (of three) of which lists, alphabetically, 42,000 officers of the British land forces who died in the First World War. While, like Officers Died . . ., this gives name, rank and date of death, it also gives one further piece of information – the place where the individual is buried or commemorated.

. . . AND PLACES . . .

This provides a further tantalising insight into the Glasgow Highlander story, but in turn raises the question: ‘Where are the “other ranks” buried?’ The answer to this, as I discovered, could be provided by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). From their enormous database they provided me with all the information they possessed, for both officers and ‘other ranks’, who, according to their records, had been in the Glasgow Highlanders.

One of the most startling things this revealed was that nearly half of those who died have no known grave and are accordingly commemorated on memorials to the ‘missing’, most particularly the Thiepval Memorial on the Somme and the Tyne Cot Memorial near Ypres in Belgium. Most of those who do have known graves are scattered in about 130 CWGC cemeteries in France and Belgium. Some are in Scotland or other parts of the UK. A small number, having died as prisoners of war, are buried in Germany.

Curiously, there are also one or two burials much further afield, including Egypt, Iraq, Israel and even Nyasaland (now Malawi). The explanation for these, as I later discovered, was that as the war progressed, some Glasgow Highlanders were attached to other units – just as some from other units became attached to the Glasgow Highlanders.

. . . THEN ‘SHOULDER TO SHOULDER’ . . .

I then found that there was, after all, a history of the Glasgow Highlanders in existence – albeit unpublished. My discovery of this came about in an odd, roundabout way – via a French book, Englefontaine et Hecq 1914–1918, by Jean-Claude Gadron. The first half of this book describes the ordeal of these two adjacent villages in Northern France under German occupation for four long years and is an eye-opening insight into an aspect of the war that British people were fortunate not to have to suffer, and know very little about.

But what was this? Glancing through the second half of the book, which deals with the great drama of late October 1918 – when the war itself came crashing into their own streets and houses – I found an eighteen-page section headed ‘Histoire Du 9ème Highland Light Infanterie, The Glasgow Highlanders 1914–1918 Par le Colonel A K Reid. Chapitre 23: Englefontaine’. A Glasgow Highlanders history? Where had he got this from? Gadron had written the book in 1986, at which time, so it said on the cover, he was a Professor of English at Valenciennes University. Perhaps he was still there, or if not they might be able to put me in touch? Within just a few days Gadron was on the phone; but even before that I had found the answer from elsewhere.

Shoulder to Shoulder, as I discovered, was written by Col Alexander Kirkwood Reid CB, CBE, DSO, MC, TD, DL, and other ex-Glasgow Highlander officers in the interwar years – but never published. In the 1980s Alex Aiken discovered it while doing extensive research of his own on the Glasgow Highlanders. He tidied it up, retyped it and distributed a limited number of copies, including to the RHF Museum and Mitchell Library in Glasgow; but it remained otherwise unpublished. This is a great pity because it expands considerably on the Glasgow Highlanders’ War Diary’s rather sparse recital of facts, and thus very much brings the Glasgow Highlanders’ story to life.

. . . COURAGE PAST . . .

I also discovered Alex Aiken’s own 1971 book, Courage Past. This tells the story of Alex’s uncle Jim (Pte 4706 James Harrington Aiken), who joined the Glasgow Highlanders in late 1915, and was then seriously wounded at High Wood on the Somme the following July. It’s an excellent piece of work, meticulously researched, and one of its most particular strengths is drawing on the personal recollections from both Jim and fifty or so other Glasgow Highlander veterans.

. . . AND MY GRANDFATHER

Shoulder to Shoulder, as I discovered, mentions my grandfather by name several times. Courage Past includes several fascinating anecdotes about how he was seen through the eyes of Aiken’s uncle and the other lads who joined the battalion in France in the early part of 1916. As for the Glasgow Highlanders’ War Diary, I also found his name mentioned once or twice, and then discovered that from May 1917 onwards it was he who had written it. It seems rather obvious to me now that he should have done this because the MoD letter told me that when he was commissioned in May 1917 he forthwith became battalion adjutant – a role which logically includes things like writing up the War Diary. But it’s not until the entry for 23 March 1918 that this notably scruffy new hand becomes identifiable when, for some reason, he appended his name to it.

On top of all that, it turned out that one of his personal files, relating mainly to his service in the Second World War, had in fact survived. So too had some photographs, including one of him taken in about 1920, when he was still in his full prime.

SO, MISSION ACCOMPLISHED?

My original objective had thus been fully met. But the problem now was that while very enlightening, what I had found nevertheless still left me intrigued. What more might there be to find?

One obvious place to look was the Internet. Curiously however the main thing this brought to light was how many other people were trying, as I had been, to find out ‘what did granddad do in the Great War?’, and how hard a struggle they were having even to find a trace – unless the person being sought was one of those who had actually died. This also brought home to me that although, from Soldiers Died . . . and Officers Died . . ., I had picked up names and other details of the 1,300 or so Glasgow Highlanders who had died, there were probably in excess of twice as many again who had served with the battalion but survived. Apart from the very few mentioned in the Glasgow Highlanders’ War Diary and Shoulder to Shoulder though, who were they?

PERHAPS NOT . . .

The answer, I was told, could probably be found back in the National Archives in Kew.

Document Series WO 329, as I was to discover, lists everyone who was entitled to a war service medal. Those who served with the Highland Light Infantry are listed in nine sub-files. Each of these is a large bound book of endlessly long typewritten lists – of surname, first name, rank, serial number; plus, where relevant, gallantry award, former unit or unit to which an individual was transferred. There are even references, where applicable, to disciplinary measures and dismissals. Another mine of information in fact – but as usual there was a snag. The lists are in regimental number order and as there is no segregation into individual HLI battalions this means that Glasgow Highlanders are intermixed with all the other HLI battalions and therefore have to be picked out one by one.

Once added to the 1,300 who died though this does create a much more comprehensive list of what then amounts to just short of 4,500 Glasgow Highlanders who served at some time in the First World War.

. . . PARTICULARLY WHEN I MAKE SOME MORE DISCOVERIES

Each of those 4,500 will have had his own individual story. Those who died were unable to come back and tell theirs and many of the survivors found it difficult to do so either.

But in addition to the recollections gathered by Alex Aiken in Courage Past, there must surely be many real-life experiences of those who fought with the Glasgow Highlanders written down somewhere . . .

So far what I have found of this sort of material is in some ways very little, but what there is of it is remarkably evocative. In the RHF Museum in Glasgow there are two excellent Glasgow Highlander personal diaries. One of these was written more or less daily by L/Cpl 2635 Thomas Thomson from the beginning of the war until late 1915. The other, written more spasmodically by Sgt 1285 James Leiper, covered the same period. These bring vividly to life what it was like to be there, suffering the cruelly harsh conditions, enduring the devastation of action – and enjoying the better times. They are a remarkable revelation, particularly when read in conjunction with the sober recitation of facts in the War Diary and the careful hindsight wording of the senior officers in Shoulder to Shoulder.

In the Imperial War Museum in London there is another personal diary covering much the same period, written by Pte 2518 Norman MacMillan, who later in the war transferred into the Royal Flying Corps and became a Wing Commander.

There are also Thomas ‘Leo’ Lyon’s highly illuminating Adventures In Kilt and Khaki and More Adventures In Kilt and Khaki. These compilations of sketches describe aspects of Lyon’s experiences with the Glasgow Highlanders from the early days of the war through to mid-1916. Lyon’s style has the raw insouciance and faux gravitas of a young man barely out of school, but this is exactly what most of the Glasgow Highlanders were. Perhaps it’s for this reason that his narratives are as much full of wit and fun as hardship and horror. The only pity is that, as per the custom of the time, the true identity of the fellow Glasgow Highlanders that he mentions have been concealed. Well, almost . . .

There is also a Glasgow Highlander story in True World War 1 Stories, a recent reprint of a compilation originally published in 1930. This is a horse’s-mouth account of what three Glasgow Highlanders got up to one day and one night in September 1918 when they were sent on a mission into enemy territory. It brings a whole new dimension to the same incident, reported in the briefest outline in the Glasgow Highlanders’ War Diary and in slightly more detail in Shoulder to Shoulder.

A STORY THAT SHOULD BE TOLD

Remarkable as they are even on their own, these real-life accounts only become truly meaningful if they are placed in context with the events to which they relate, as set out in the Glasgow Highlanders’ War Diary and Shoulder to Shoulder. These latter, in turn, are greatly enlivened if read in conjunction with the personal anecdotes. Bringing them together though, and working out how the Glasgow Highlanders’ story fits in to what was happening in the war as a whole, does turn all these otherwise obscure and disparate documents into a fascinatingly cohesive whole.

And that’s why I’ve written it down. Despite many remaining gaps it’s a story that should be told – and I hope at any rate that it enables fellow descendants of those 4,500 Glasgow Highlanders to find some clues about ‘what granddad did in the Great War’. It has already done so for Ian Hislop, as it enabled the sequence in the television series Who Do You Think You Are? featuring his grandfather to be put together.

1

HIGHLAND ORIGINS

THE GREAT CITY OF GLASGOW

There’s nowhere quite like Glasgow. The sheer dynamism of the place has meant that its name – and reputation, warts and all – has been stamped all round the world. Glaswegians have liberally populated the globe, perhaps to reminisce affectionately about ‘The Dear Green Place’, which is what the name Glasgow means in Gaelic.

Green it may indeed still be, particularly because of its enviable location so close to beautiful countryside, but Glasgow, geographically, is nevertheless in the Scottish Lowlands – which might make the name Glasgow Highlanders something of a puzzle. . . .

WILD AND WARLIKE HIGHLANDERS

It takes only a very quick backward glance at Scottish history though to understand why there is nothing contradictory in the Glasgow Highlanders’ name.

The Romans rather gave up on Scotland, the furthest northern extremity of their vast empire, and in due course drew a line, or in fact built a wall, to mark where their kind of living ended and that of the wild Scots to the north began. Many subsequent invaders did successfully colonise Scotland, but although most of these – Vikings, Angles, Saxons and Normans – also stamped their mark on England, the resulting Scottish gene pool remained a distinctly different brew.

For centuries the two separate nations of England and Scotland were regularly in conflict, but by the Act of Union in 1707 became one nation. This meant the discontinuance of the Scottish monarchy and parliament and many Scots felt that the only benefits arising from it would be to the English – the ‘auld enemy’, as they saw them. But the resistance movement the Scots mounted was hampered by their poverty – and by the Scots tradition of in-fighting – and at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 the rebels were decisively defeated and their potential new Scottish king, Bonnie Prince Charlie, put to flight.

The English, determined to root out the age-old problem of the troublesome Scots for good, then embarked on the draconian programme of what we, today, would call ethnic cleansing. Under the clearances, clan chiefs were forced to give up their powers and swathes of tenant farmers evicted from the land. As a consequence, the economics of much of the Highland community collapsed and many of the population were forced to pack up and leave, many going off to the colonies, particularly America and Canada.

‘MY GOD THEY FRIGHTEN ME . . .’

Some though joined the British army. In those days, although the regular army attracted – to its officer ranks – recruits from some of the most eminent families, the common soldiery tended, in contrast, to come from the most disadvantaged elements of society.

Wellington’s way of putting it, uninhibited by concerns about political correctness, was that ‘We have in the service the scum of the earth as common soldiers.’ Another of Wellington’s remarks (variously misquoted these days along the lines of not knowing what effect these troops have on the enemy, but my God they frighten me) is actually a perfect fit for the Scottish soldiers that were part of the armies that he led successfully against Napoleon. Following the Battle of Culloden, part of the repression imposed by the English on Scottish militarism were bans on wearing tartan and playing bagpipes, both regarded as inflammatory symbols or instruments of war. But Scots who joined the British army were allowed to deck themselves out in their full warlike gear – and to terrify their enemies with the sound that went so perfectly with it, the skirl of the bagpipe.

THE FLOURISHING OF GLASGOW

Following Wellington’s final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, armies were stood down and the period of relative peacefulness which then followed was marked by the new phenomenon of the industrial revolution. British inventiveness, in particular the key development of steam power by Scots-born James Watt, gave Britain a short lead on the rest of the world, and the rapid transformation of industry from small workshop to large factory made a big impact on places that had the key ingredients – coal and iron – readily available.

Glasgow found itself ideally placed to exploit the new opportunities. Already for many years a merchant port, in particular importing raw cotton and linen and exporting finished cloth, the thing that really made it take off, from the latter part of the eighteenth century, was the fact that it also had the coal and iron needed for the new heavy industries – together, somewhat fortuitously, with a large influx of displaced Highlanders desperate for jobs.

Glasgow became a boom town. Even by 1800 its population of 77,000, although meagre-sounding by today’s standards, made it one of the largest cities in the British Isles. It continued to mushroom, and by 1861 its numbers had quadrupled to about 385,000, which meant that it comfortably maintained its lead in size over Birmingham, Liverpool or Manchester.

The union of Scotland with England was now seen to be an advantage because of the much expanded trade that opened up with the British colonies. And when shipbuilding switched from wood to steel hulls, Glasgow was in the perfect position, which its entrepreneurs took full advantage of, to become shipbuilders to the world. Fortunes were made, and the huge 150-yard-tall chimney of the Tennant’s St Rollox chemical factory became a symbol of the enterprise, free trade, and prosperity of the city. It was huge enough to be visible all over the city – smog permitting.

As well as the very evident pollution from the factories, the working conditions and living standards of Glasgow’s masses were dreadful. Glasgow became known around the world both for its fine engineering products and its slums, reputed to be the worst in Europe, and fresh waves of rural poor kept on pouring into the city, including many fleeing starvation in Ireland as a result of the potato famines. The grossly overcrowded and insanitary living conditions of many of the workers led to outbreaks of disease including cholera and by the mid-nineteenth century it became imperative to clean the place up. It was decided that the old slums must be torn down and replaced by new mass housing, with sanitation, and that the city centre should be rebuilt with grand boulevards and public and commercial buildings worthy of what had become the largest and wealthiest of any of Britain’s cities outside London.

SECOND CITY OF EMPIRE

Edinburgh, since union with England, had grown at a much slower pace than Glasgow; but although it was no longer the seat of throne or parliament it remained the Scottish capital. As there was no likelihood of Glasgow being able to pinch that title, the ingenious solution was to invent a new one which overrode not just Edinburgh but also all the major cities of England as well. Glasgow coined for itself the title ‘second city of Empire’.

Great strides were made in creating a city that looked the part, and efforts were also made to deal with the city’s huge social problems. Education for the masses, generally considered better in Scotland than England, had largely bypassed many of Glasgow’s poor, and the consequences of this, together with poor health, malnutrition – and drink – could not quickly be resolved. Alongside Glasgow’s exceptional hard-drinking culture, sections of the Scottish Church tried to preach the alternative extreme of total abstinence, and this did meet with some success, but mainly from the emerging middle classes who wanted to distance themselves from the hoi polloi.

BUT WHO’S LOOKING AFTER THE GOLDEN GOOSE?

Meanwhile Glasgow’s preoccupation with trying to make its city and institutions fittingly better than ever before, or anywhere else, didn’t blind its worthies to the fact that they had to look after the golden goose. Glasgow’s wealth was created primarily from the trade that came in or went out on the River Clyde, and much of this was derived from either England or the British colonies. The British Empire had blossomed as no empire had ever done before on the back of the new industrial age, but what was happening in the rest of the world?

For over thirty years after the British, with the help of the Prussians, defeated Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815, Europe was more or less at peace. But by mid-century troubles flared again – in Austria, Germany, Hungary and Italy. Russia, for its own defences but also in the name of Christianity versus the Muslim Turks, wanted to improve its position around the strategically important Black Sea and this led to war in the Crimea, with the French and British siding with the Turks against Russia. The outcome destabilised both the losing Russians and the supposedly victorious Turks.

British forces in the Crimean War were relatively minor by comparison with the main protagonists (the Russians and Ottomans), and also significantly less than the French, but the death rate of all participants was very high, and Britain’s self-confidence plummeted after it lost 22,000 men in a campaign that exposed many inadequacies in its military capabilities. Elsewhere in Europe, new nation-states such as Bulgaria, Romania and Serbia gained independence, and Italy’s states became a united nation. Perhaps of the greatest significance though in the light of what was to come, the Austrian Empire weakened, and this led to the unification of the states of Germany and the rise of Prussian militarism.

At the time though the most important threat to Britain was still believed to be France. After a coup d’état in 1851 France had a new Emperor, Napoleon III, and there were big worries as to what he might get up to. The government spent a great deal of money building new fortifications on the English south coast against possible invasion, but was this enough? Many thought not, and as a result it was agreed that the defences of the nation, and its world-wide trade routes, should once again be supplemented by setting up part-time civil defence volunteer forces. One of these became the Glasgow Highlanders.

IT ALL STARTED IN A PUB

When the green light was first given for citizens to create voluntary civil defence organisations, the Celtic Society in Glasgow attempted to inaugurate three. The first of these, started in 1860, was called the 60th Glasgow (1st Highland) Company, and there then followed the 61st (2nd Highland) Company, and the 63rd. But these were small organisations destined to be short-lived. By 1863 there were new rules which meant that volunteer companies had to be of adequate size and properly organised – in exchange for which the government would pay for an adjutant and instructors and a capitation allowance.

Against this background the idea of setting up a proper volunteer force of Highlanders became a talking point, and nowhere more than in the Athole Arms. This was a ‘Highlanders’ pub’, which meant that many of its patrons were exiles from the Highlands – or their fathers or grandfathers had been – and as is the way of exiles they perhaps felt more fiercely bonded in their new environment than they would ever have done back where they came from. Although the pub itself is now long-gone, parts of Dundas Street in which it was situated are still there, very much in the centre of Glasgow, alongside Queen Street station, and hence just off George Square.

In due course seven of the Athole Arms regulars – Thomas D. Buchanan and James Menzies being the ringleaders – agreed to hold a meeting to talk seriously about the subject. Thus on Monday 30 March 1868 they assembled purposefully in one of the Athole’s private rooms. Before getting down to business they rang the bell. Lachie, the waiter, was ordered to bring in a supply of whisky and cigars and to ask the landlord, Sandy Gow, to join them. ‘Got bless me, what’s ado tonight?’ asked Gow as he was invited to sit down and fill his tumbler – but that, so the story goes, is what he was always saying. What was up was that they had broached their idea to the Lord Lieutenant of Lanarkshire – who had said that he was surprised that it had taken until now to be asked; and yes, he thoroughly approved of Glasgow having a volunteer Highland battalion. They resolved to get on with it, Sandy Gow, their ‘genial and enthusiastic Highlander host’, agreeing to be on board.

PLENTY WANTED TO JOIN

A public meeting was organised. The Sheriff Clerk was lined up to chair it, with the Celtic Society there in full support. When it was held, at 2000hrs on Monday 27 April 1868 at the Merchant Hall in Hutcheson Street, it drew ‘one of the largest and most enthusiastic meetings of Highlanders that had ever taken place within the City of Glasgow, hundreds being unable to gain admission’ (The Pibroch). No fewer than 600 signed up at that first meeting. A committee of twenty-one was appointed, and the minutes of the meetings held over the ensuing months were written up in copperplate handwriting in a small bound book that smells to this day of smoke.

THE RIGHT CONNECTIONS

Having already ensured that the Lord Lieutenant, the Sheriff and the Celtic Society were firmly on side, there were further critical matters of protocol which they still had to get right – not the least being Royal Assent. But they seemed to have had all the necessary connections, and with the assistance of the Lord Provost of Glasgow their application duly went off to the Queen. Their spadework having all been done, the formal response took very little time to come back and they were granted permission to form ‘The Glasgow Highland Rifle Volunteer Regiment’ – and to wear the uniform of the Royal Highlanders. Off they went to their tailors.

KEY APPOINTMENTS

And off went nominations for commissions, an initial batch of twelve of which were granted in September 1868. Others, up to an initial complement of twenty officers, followed shortly. They also needed to appoint the necessary key players – an adjutant to handle the administration, a Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) together with a couple of assistants to take charge of instruction and training, and a pipe-major.

In due course Lt James H. Hay from the 89th Regiment was recruited as adjutant, Sgt Maj William Clayton as RSM, and Pipe-Sgt McPhail as pipe-major.

When, twenty-five years later, the Glasgow Highlanders first ventured ‘with mixed feelings of doubt and apprehension’ to launch their in-house magazine, The Pibroch (the name for a piece of bagpipe music) they felt that the application letter from one of the failed candidates for pipe-major was by then quaint enough to be reproduced in their version of an ‘all-our-yesterdays’ column:

Bankfoot, 30th September 1868: Mr Gow

Dear Sir – I want mad piper matcher of your regiment and I no you can put me in. My play is goot. I got it from John McGregor, who played the Duce of Athole at the Eglitun Toornament, and Lord Waterford was there, also ye’ll mind you was yourself there too. I dinna care for muckle pay, but I would like fine to see a first class band as you are an officer, and am very proot. I am first prize at Kirkintilloch and second marches at Bridge O’ Allan. No more at present but hopes you’ll mak me pipper matcher of your regiment. My wif says she no you at skull and would like fine to come to Glesko.

Yours truly, Donald McGlashan

All in all it seems quite a good CV – if you forgive the spelling. The final initial appointment was the Revd Gunn, who was to be appointed chaplain ‘for spiritual comfort’.

THEY GOT THEMSELVES NOTICED

Life must have felt very exhilarating for these denizens of the Athole Arms in the summer of 1868. The city they lived in was one of the largest in the most powerful empire in the world, and more and more people like themselves were benefiting from the prosperity which that brought. In addition they could also now present themselves so much more visibly to the world as the traditional Highlanders which, with great pride, they felt themselves to be.

And even as they organised the basic structure of their new baby, the first opportunity to appear in very public view came along when they learned that the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) was coming to Glasgow on 8 October 1868 to lay the foundation stone for the new Glasgow University building. With remarkable fleetness of foot, and demonstrating yet again how these boys knew who to talk to and how to get things done, they first obtained the necessary permissions and then rushed to get as many as possible of their recruits kitted out with uniforms. They appointed a Mr Hugh Morrison as regimental tailor, and by the day of the royal visit, which had been declared a special public holiday in Glasgow, 126 men, 15 officers and the adjutant managed to turn out in the new uniforms.

They assembled in St Enoch Square in the city centre and then marched to the university grounds in Kelvingrove Park where they took up their appointed position by the new wooden bridge across the River Kelvin. The Prince of Wales was said to have ‘taken special note of the Glasgow Highlanders’ who, together with regulars, had thus lined his route.

They had certainly got their exposure, and this meant that it was all the more vital that what they were setting up was soundly based and would not fizzle out. It would almost certainly do just that if they didn’t get their government funding – and their application for this had not yet even been submitted. Volunteers only got the potentially available government capitation grant if they were accepted as a credible organisation, and this required a formal review by a senior officer from the regulars. To get them off the ground – or otherwise – the Glasgow Highlanders presented themselves to Col Bulwer CB on 9 November 1868.

But they passed muster. They were up and running.

THERE WAS THE IMPORTANT MATTER OF UNIFORMS

When Queen Victoria gave them the go-ahead their official designation was ‘105th Lanarkshire Volunteer Corps’, but by allowing them to wear, at least in part, the uniform of the Royal Highland Regiment, she acknowledged that although based in lowland Glasgow (in Lanarkshire) they were to be recognised as Highlanders. And this meant kilts. The Royal Highlanders (also known as The Black Watch) dated back to the early days of union between England and Scotland when, following the ban on Highlanders bearing arms or wearing their warlike tartans, the process of keeping the peace had involved setting up new, British, loyalist forces, a means by which Highlanders could have a job and also wear their traditional dress. According to instructions though the tartan for the Royal Highlanders was to be ‘as near as can be of the same colour’, and it had to be very sombre – totally in contrast to the red coats and white breeches of the English regiments. This quickly gained them, and their carefully toned-down tartan, the nickname ‘The Black Watch’. Although the colours later became modified, they remained a mixture of dark green, dark blue and black, and this is now, today, probably one of the few tartans that is universally known and recognised.

Over the decades which followed its origins in 1868 the finer details of the Glasgow Highlanders’ uniform did change from time to time, but the essentials remained, even through successive reorganisations. In the first of these, in 1880–1, the Glasgow Highlanders were redesignated the ‘10th Lanarkshire Volunteer Rifles’ and became a volunteer battalion of the newly reorganised Highland Light Infantry (HLI).

For about 100 years previously the two regiments that were at that time amalgamated to become the HLI were ‘The 71st Highland Light Infantry’ and ‘The 74th Highland Regiment’. Although predominantly Highland in origin their base at that time became Lanark and because of that the HLI evolved in due course to be the regiment most associated with Glasgow.

Back in 1779, in the days when the English were still cautious about allowing Scots too much freedom to wear their traditional dress, the 71st, when sent to India, had been ordered to wear trews (tartan trousers) rather than the kilt. The 74th accordingly also wore trews. At amalgamation in 1880–1 they were given the opportunity to revert to the kilt but declined – and then almost ever afterwards regretted having done so. The Glasgow Highlander volunteers though, probably because they were not regarded at that time as proper soldiers, were free to hang on to their kilts.

Regiments thrive on strong feelings of identity and belonging, and uniforms play a very important part in this. Looking back today at old photographs it’s often possible, by studying the precise details of the uniform, to identify what unit and what time period is involved. But it’s also very easy to be misled. Within just one battalion there can be different outfits not only for different categories of officer, and various ranks, but also for ‘dress’, ‘undress’, ‘ceremonial’, ‘drill’, ‘fighting’, and so on. So even if a picture shows something as definitely identifiable as a kilt it doesn’t necessarily mean that the unit as a whole was kilted – it’s perhaps just that the individual in question was in the band.

HIGH IDEALS

The Glasgow Highlanders, having got off to a flourishing start by showing themselves off to the Prince of Wales – and thus to much of Glasgow and the many visitors who had crowded into the city for the royal visit, including the guard of honour of regulars – continued to blossom. Within just two years of their inception the alarm in Britain about a possible new threat from the French all but disappeared after Napoleon III decided that the way he would make his mark was by attacking Prussia. The resulting disaster for France, in what is now known as the Franco-Prussian War, brought them decisive military defeat and the loss of great swathes of territory rich in coal and iron in the north-eastern regions of Alsace and Lorraine. It also saw off the Emperor, and France settled down to brooding about how, some day, it might re-settle the score.

Britain, still in the heyday of imperial power, thus no longer felt the need to worry about invasion from the French, and was not – yet – much bothered about the Prussians. Britannia ruled the waves, courtesy of the Royal Navy, and the regular army would do whatever else was necessary to protect British interests at home or around the world. As for the volunteers, they were not really part of the equation – whatever they themselves might imagine. But at least they were not stood down after the Franco-Prussian War, as had happened after Waterloo.

So the Glasgow Highlanders got on with what they were determined to do, to attract the best type of recruit who would at least be basically trained and whose enthusiasm, spirit and loyalty would build a force which would have real capabilities – should the occasion some day arise.

For the thirty years that followed its 1868 inception, what this meant in practice was that the Glasgow Highlanders were essentially a combination of shooting club, gym and gentleman’s club. The basic criterion of being a ‘Highlander’ was upheld, more or less, and due probably to the fact that many of the descendants of that particular gene pool were in any case relatively tall and well built, it became a requirement that recruits should have a good physique. In those days the normal height minimum for getting into the regular army was 5ft 3in and the Territorials often accepted 5ft 2in. But the Glasgow Highlanders wanted their men to be as big as the Scots Guards, which meant being at least 5ft 7in tall and with a chest measurement of 33½in.

The target complement for the battalion was about 1,000 men. Within a couple of years there were over 800, and by 1881 the 1,000 mark had been passed and was thereafter sustained. Many individuals of course came and went. Being a volunteer appealed mostly to men in their late teens and early twenties. It was a natural follow-on from school, and an accompaniment, for many, to life at university. It was a great way to get or keep fit, shoot, play sport and socialise. There was also the opportunity, for those who wished, to take on the advantages, or otherwise, of working up the battalion hierarchy ladder – from private to lance-corporal, to corporal, to lance-sergeant, to sergeant, and then to colour-sergeant. And because many of the Glasgow Highlanders had the necessary education and social standing, plenty were eligible to move on from there to become officers. In this respect the Territorials were materially different from the regular army that they otherwise tried so hard to emulate because ‘other ranks’ in the regulars rarely managed, at that time, to jump the big divide between officers and men.

CLAN VALUES

By 1898 the serial number of newly recruited Glasgow Highlanders had reached over 8,300, having started at 1 three decades previously. So the twenty-somethings of the earliest days were now fifty-somethings and mostly now long gone, at least as active members. But like many successful associations, the ties did not necessarily break just because the days of active drill and annual camp were left for those with younger limbs. The Glasgow Highlanders, as a club and an institution, entered the psyche of many who passed through it, so by the end of the century, although nominally the complement was just over 1,200, there were many more ex-members, whether or not formally still associated, who were, at least in spirit, still part of the battalion.

This clannishness was very deliberately fostered. When, in 1895, The Pibroch was launched, the message coming through loud and clear from its pages was about the importance of the battalion’s values. There were regular articles emphasising how they were a clan, and what sterling chaps the members of this clan all were.

A great deal of space was given to the results of shooting competitions, both as to scores and to who were the prizewinners. Other regular competitions involved such things as signalling, use of bayonet, and ‘Wappenschaw’ (an old Norse term used by the Scots ‘to show that they are properly armed’, and adopted by the military at the time as a defined drill exercise).

One of the ‘all-our-yesterdays’ articles in The Pibroch even listed both the prizewinners and prizes for the Annual Regimental Wappenschaw held on Saturday 26 May 1877. If it seemed quaint enough to reproduce in 1898 it inevitably seems even more so today. D. M’Leod of No. 7 Company was awarded a pair of trousers, Colour-Sgt Thomson of No. 8 Company a silk hat. James Steel of No. 2 Company received a butter cooler, and quite a number of them got table cutlery of various kinds. There were forty-five prizes for other ranks and nine for officers. The latter were given somewhat more upmarket things, like champagne knives and silverware, but silver was also given to Sgt Maj Clayton in the form of a thimble, and even in 1898 they wondered what use this might have been to him. Another CSM, M’Creadie, won a live turkey, and they recalled how the inevitable happened. After escaping from his clutches it took a long time to be recaptured, rumour having it that persuasion from one of the marksmen’s rifles was needed ‘to bring it to reason’.

SOME OF THEM WENT TO THE QUEEN’S JUBILEE

1897 was the year of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, and for this occasion the War Office pronounced that it would allow a limited number of Scottish volunteers to join the ceremonial parades in London. Naturally of course the Glasgow Highlanders wanted to be there – but first there was the question of how to pay for it. The government was willing to contribute only 2s per head towards costs, but as the lowest price they could negotiate on the rail fare alone was 25s per head there was obviously going to be a big shortfall. Not to be deterred however the battalion eventually agreed that those who went would pay no more than 20s out of their own pockets and that the Glasgow Highlanders’ funds would take care of the balance.

Thus, off went seventy-five of them on the overnight train on 21 June 1897, together with a contingent of 1st and 3rd Lanark Volunteers. They were too excited to get much sleep, so spent much of the night singing songs or playing cards. After they arrived at London’s Euston station they formed up and marched behind their pipers to Hyde Park. There they joined the many other British regiments that had come together to disport themselves in front of the Queen. The vast crowds of Londoners were fascinated by the pomp and ceremony – and by the novelty of the sight and sounds of the Highlanders. It was a unique day too for the men from Glasgow, most of whom had never before been south of the border. By 1630hrs they were back at Euston, but as their night train to Glasgow didn’t leave until 2335hrs there was still plenty of time to mill around, talk to the locals – and have a few bevvies. They obviously managed to cope with this well enough though to be all present and correct for the departing roll-call and the long journey back to Glasgow – this time falling asleep almost immediately.

As usual their uniforms confused onlookers. Civilians had shouted things like ‘Bravo Gawden ’Ighlanders’, the cockney emphasis on the ‘land’ sounding very strange to Scottish ears, and HRH the Duke of Cumberland had ridden up to Lt Alexander Duff Menzies to enquire, ‘Are you from Perthshire?’ ‘No sir, we come from Glasgow.’ ‘But you wear the uniform of The Black Watch?’ ‘Yes sir, we are the Glasgow Highlanders.’ ‘Oh, yes’, concluded the Duke, ‘that is the regiment that Lord Lorne was Colonel of. Your men are looking very smart and tidy after their long journey.’

And naturally this latter remark had made them feel several inches taller.

LOTS WENT TO SUMMER CAMP

Each mid-summer the Glasgow Highlanders went off out of town, usually to Gailes camp on the Ayrshire coast near Troon where they joined up with other volunteer battalions at summer camp. For those who liked that sort of thing – drills, competitions, target-shooting, sport, mock battles for a week or so while sleeping eight to a small tent and in the company all the time of just thousands of men – annual camp was probably one of the best things about being a volunteer, and unlike the regulars, whose lifestyle this was all the time, the volunteers knew that within a few days it would all be over and they would be back home again.

‘HAPPY AS BEES’

In 1897, just a short while after the Jubilee trip, there was a special summer camp at Aldershot, one of the main homes of the British regular army, situated in the south of England. No fewer than 425 Glasgow Highlanders went off on this jamboree and if they were all like ‘Sandy of F Company’ there was no question that they enjoyed it.

Sandy’s letter to his wife in Rothesay was reproduced at the end of a lengthy write-up on the Aldershot adventure, and despite his rather colloquial style, the picture does shine through:

Dearest Betsy, Bourley Camp, Aldershot.

Love an’ best wishes to ye. I am weel eneuch, but I thocht we were never goin’ to get to Aldershot, but we have gotten there a’ the same. The whisky that ye gied me before comin’ awa’ was feenished before we got to Hellafield, – funny name, isn’t it? but it’s richt. Ye were a bad judge when ye tellt me that ae bottle o’whisky wid dae me. A’ the chaps had a bottle each, same as me, an’ it wisna enough, because we had to jump oot at every station for watter efter the whisky was done, an’ the watter wis faur scarcer than the whisky. It took us a’ oor time to get a’ moothful each. Well, Betsy, we’re a’ at Aldershot noo, an’ as happy as bees, carryin’ a’ before as Hielanders always do. We’re camped in a verra nice place beside trees, an’ the grub’s good, an’ the whisky an’ beer are no’ bad at a for sich an oot-o’-the-way place like this . . .

And on he went at some length in much the same vein, until signing himself off with:

It’s near tea-time noo, so I’ll just stop. Wishing you good weather at Rothesay, plenty o’ kisses an’ a nice hug when I come back. – Your loving Sandy (Private, F Company.)

‘THE PLEASURES OF WINTER’ WERE ENJOYED

Although most of the week-by-week drills and keep-fit activities of the Glasgow Highlanders were organised within companies, of which, at least in the late 1890s, the battalion had twelve, each comprising about 100 officers and men, there was also a year-round calendar of events which from time to time brought the battalion as a whole together. In spring there was a traditional Easter route march, then throughout the summer various shooting competitions, sports events and church parades – as well as summer camp, of course.

By November though ‘the pleasures of the winter were looked forward to’, as Charles MacDonald Williamson, successor as the Glasgow Highlanders’ Commanding Officer in place of Lt Col F. Robertson Reid by the late 1890s, put it in one of his CO’s reports in The Pibroch. The officers got the festive season started with ‘at homes’, but in mid-December the really big annual event of the winter – the Glasgow Highlanders’ Annual Gathering – was held. For this the battalion took over St Andrew’s Hall, the largest in the city, and the event, which was also attended by the men’s families and lots of ‘old boys’, was acknowledged to be one of Glasgow’s major social occasions.

BUT WERE THEY REAL SOLDIERS?

Thus, by the end of the nineteenth century the Glasgow Highlanders had become a Glasgow institution. And it continued to attract a steady influx of high-calibre recruits. One such was Commanding Officer-to-be Charles Crawford Murray. Having passed through the ranks in the 1st Lanarkshire Volunteers he was commissioned and then joined the Glasgow Highlanders as a Second Lieutenant. He subsequently obtained the ‘Passed School’ general military certificate, together with other exams including tactics and military horsemanship. He was also a renowned gymnast and enthusiastic piper.

There are other profiles of similarly keen young Glasgow Highlander officers in The Pibroch, but despite all their hard work at developing their soldierly skills they were, at the end of the day, just part-timers, and at least in the eyes of the regulars this meant that they would need a lot more training before there could be any question of them doing any real soldiering.

. . . AND WHAT HAPPENED WHEN THE SOUTH AFRICAN WAR CAME?

Even before the outbreak of the South African War the Glasgow Highlanders, scenting what was brewing, determined to show the doubters that they were willing and indeed able to fight alongside the regulars. They offered what amounted to a half battalion – but were turned down.