22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

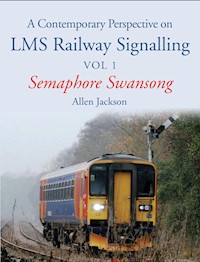

For over 150 years Britain's railways have relied on a system of semaphore signalling, but by 2020, all semaphore signals and lineside signal boxes will be gone. In his previous book, author Allen Jackson covered the GWR lines; here, he continues his journey by providing a pictorial record of the last operational signalling and infrastructure on Britain's railway network, as it applied to the former London, Midland and Scottish Railway (and lines owned jointly with other companies). This second volume covers the routes of the following companies: London and North Western Railway; Caledonian Railway and Highland Railway.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

A Contemporary Perspective on

LMS Railway Signalling

VOL 2

Semaphore Swansong

Allen Jackson

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Allen Jackson 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 073 7

Frontispiece: Llandudno station signals and box, January 2015.

Dedication

For Ninette.

Acknowledgements

The kindness and interest shown by railway signallers, including David Dawson, David Horton, Alan Roberts.

Contents

Preface

Introduction

1 Signal Boxes and Infrastructure on Network Rail

2 London and North Western Railway (LNWR)

Whitehaven to Carlisle

North Lancashire

Crewe to Shrewsbury

Crewe to Chester and Holyhead

Manchester to Buxton

Wirral and Runcorn

Widnes to Warrington

Manchester Area

Liverpool Area

South Cheshire

Staffordshire

West Yorkshire

South Midlands

3 Caledonian Railway (CR)

Clyde–Forth Valley to Perth

Perth to Aberdeen

Glasgow

4 Highland Railway (HR)

Useful Resources

Index

Preface

The GWR book in this series concentrated more on the ways of working, and while it would be easy and more lucrative to refer readers back to that volume, some explanations of those features have been incorporated in this work. I apologize if this seems slightly repetitive if you have already read the GWR book but I feel there will be some who have not. In addition the Scottish ways of working differ somewhat, so they are explained here.

Many main lines have not seen mechanical signalling for thirty or more years, and so the emphasis tends to be on the secondary lines.

The survey of what is left of the mechanical signalling on Network Rail took place from 2003 and 2015, really at the advent of usable digital photography.

While this was being done some of it disappeared before I could get to it and so there may be omissions.

With improvements in digital equipment and the means to pay for it, a good deal of what remains has been revisited in the last twelve months.

Fig. 1 Stirling Middle signal box with some of its signals, August 2003.

Introduction

Up until 1 January 1923 there were hundreds of railway companies in Britain. The government at the time perceived an administrative difficulty in controlling the railways’ activities at times of national crisis. The country had just endured World War I and the feeling was that it could all be managed better if they were amalgamated. Thus came the railway ‘grouping’ as it was termed, creating just four railway companies.

The London Midland and Scottish Railway was one of those four entities but the identities of the larger companies within it persisted and does so to this day. Lines are referred to by their pre-grouping ownership even now. This is often because routes were duplicated and so it was never going to be accurate to refer to the line from ‘London to Birmingham’ without the qualification ‘London and North Western’, if that was the one being referred to. This was to differentiate it from the lines run by the Great Western.

Many of the smaller companies did lose their identity, in signalling terms, although their architecture may remain.

The only pre-grouping railways considered therefore are those for which an identifiable signalling presence existed at the time of the survey.

There are so many ex-LMS signal boxes and infrastructure that it has been necessary to split the LMS into two.

Volume 1 covers:

Midland Railway (MR)

Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (L&YR)

Furness Railway (FR)

Glasgow and South Western Railway (GSWR)

North Staffordshire Railway (NSR)

Volume 2 covers:

London and North Western Railway (LNWR)

Caledonian Railway (CR)

Highland Railway (HR)

This splits the journeys to the North and Scotland into two distinct routes: Volume 1 covers the Midland over the Settle–Carlisle, then GSWR to Glasgow; while Volume 2 covers the LNWR and CR route of the West Coast Main Line and on by the Highland Railway to Inverness.

In the book the system of units used is the imperial system which is what the railways themselves still use, although there has been a move to introduce metric units in places like the Railway Accident Investigation Branch reports and in the south-east of England where there are connections to the Channel Tunnel.

CHAPTER 1

Signal Boxes and Infrastructure on Network Rail

The survey was carried out between 2003 and 2015 and represents a wide cross-section of the remaining signal boxes on Network Rail. Inevitably some have closed and been demolished, while others have been preserved and moved away since the survey started. The large numbers of retired or preserved signalling structures have not been considered in this work and are to be held over for a future volume.

Although the book is organized around the pregrouping companies, the passage of time has meant that some pre-grouping structures have been replaced by LMS or BR buildings.

If you are intending visiting any of them it is suggested that you find out what the current status is before you set off.

For reasons of access and position some signal boxes are covered in greater detail than others and some are featured as a ‘focus on’, where the quality of the information or the interest of that location merits that attention.

Some of the signal boxes have been reduced in status over the years, and while they may have controlled block sections or main lines in the past, some no longer do so but are (or were at the time of the survey) on Network Rail’s payroll as working signal boxes.

Details of the numbers of levers are included but not all the levers may be fully functional, as signal boxes have been constantly modified over the years.

Lever colours are:

Red

Home signals

Yellow

Distant signals

Black

Points

Blue

Facing point locks

Blue/brown

Wicket gates at level crossings

Black/yellow chevrons

Detonator placers

White

Not in use

Green

King lever to cancel locking when box switched out

Levers under the block shelf or towards the front window normally are said to be normal, and those pulled over to the rear of the box are said to be reversed.

There are some boxes where the levers are mounted the opposite way round, in other words levers in the normal position point to the rear wall, but the convention remains the same.

Listed Buildings

Many signal boxes are considered to have architectural or historic merit and are Grade II listed by English Heritage or Historic Scotland. This basically means they cannot be changed externally without permission. If the owner allows the building to decay to such an extent that it is unsafe, the building can then be demolished. The number of signal boxes with a listing is due to increase on the news that they are all to be replaced by 2020.

A Grade I listing would require the interiors to remain the same so that is unlikely to happen with Network Rail structures but may happen with the preservation movement – many boxes have had the interiors preserved as fully operational working museums.

In Scotland the classification system is somewhat different and is as follows: Category A for buildings of national or international architectural worth or intrinsic merit; Category B for buildings of regional architectural worth or intrinsic merit; Category C for buildings of local importance, architectural worth or intrinsic merit.

Signal Box Official Abbreviations

Most signal boxes on Network Rail have an official abbreviation of one, two or sometimes three letters. This usually appears on all signal posts relevant to that box. Finding an abbreviation could be tricky – for example there are eight signal boxes with Norton in the title – until you realize that they are not unique. The abbreviation for each box appears after the box title in this book, if it has one.

Ways of Working

Absolute Block – AB

A concept used almost since railways began is the ‘block’ of track where a train is permitted to move from block to block provided no other train is in the block being moved to. This relies on there being up and down tracks. Single lines have their own arrangements. It is usual to consider trains travelling towards London to be heading in the up direction, but there are local variations and this is made clear in the text.

This block system was worked by block instruments that conveyed the track occupancy status and by a bell system that was used to communicate with adjacent signal boxes.

Signal Box A

Signal Box B

Activity

Bell Code

Activity

Bell Code

Call attention

1

Acknowledge

1

Line clear for express?

4

Acknowledge Line is clear for express

4

Train entering block section

2

Acknowledge Train entering block section

2

Acknowledge Train leaving block section

2.1

Train leaving block section

2.1

The signallers rely on single-stroke bells for box-to-box communication – although this is supplemented by more modern means, the passage of trains is still controlled this way. A typical communication for the passage of an express passenger train (Network Rail Class 1) from signal box A to signal box B would be as shown on page 9; the text in bold is the instigator and that in plain text the reply.

Each time an action is carried out, the train’s situation is recorded on Signal Box A’s instrument and reflected by block instruments by the signaller at Signal Box B, who is the receiving box.

The status of a block can be one of the following:

Normal – Line Blocked

Line Clear

Train on Line

This procedure is repeated along the line to subsequent signal boxes. The absolute block system refers to double lines and the above procedure is designed for one line of track only. With double track it is not unusual to have two sets of dialogue between adjacent boxes as trains pass each other on separate lines.

In our example, although only the up line has been shown, a train could be travelling from A to B on the up line and another train on the down line from B to A.

Track Circuit Block – TCB

Track circuit block is really all to do with colour light signals, which, strictly speaking are outside the scope of this book, except that many signal boxes interface to track circuit block sections and will have track circuit block equipment or indications in them.

Originally track circuits lit a lamp in a signal box to indicate where a train was. Then they were used to interlock block instruments, signals and points together to provide a safe working semaphore signal environment.

With colour light signals it is possible to provide automatically changing signals that are controlled by the passage of trains or presence of vehicles on the track. The Train Out of Section of AB working can be reproduced technologically by using axle counters. To quote the memorable words of BBC reporter Brian Hanrahan during the Falklands War – ‘I counted them all out and I counted them all back’ – that’s all axle counters do and if the numbers are not equal, signals are turned to red.

Single Line Workings

These – key token, tokenless block and no signaller key token, one train working and one train staff – are covered in detail in the section on the signal box that supervises such workings.

The suffix (i) behind a box title indicates interior views.

Fig 2 Class 156, 156 472 approaches Wigton station under the eagle eye of the signaller on the Cumbrian Coast Line, December 2014.

Summary of Disposition LMS Volume 2

London and North Western Railway

Whitehaven to Carlisle

Bransty

Parton

Workington Main No. 2

Workington Main No. 3

Maryport

Wigton

North Lancashire

Bare Lane

Hest Bank Level Crossing Frame

Crewe to Shrewsbury

Gresty Lane No. 1

Nantwich

Wrenbury

Whitchurch

Prees

Wem

Harlescott Crossing

Crewe Bank

Crewe Junction

Severn Bridge Junction

Crewe to Chester and Holyhead

Crewe Steel Works

Beeston Castle and Tarporley

Mold Junction

Sandycroft

Rockcliffe Hall

Holywell Junction

Mostyn

Talacre

Prestatyn (i)

Rhyl

Abergele

Llandudno Junction

Llandudno Branch

Deganwy

Llandudno

Blaenau Ffestiniog Branch

Glan Conway Station

Llanrwst North

Blaenau Ffestiniog Station

Penmaenmawr

Bangor

Llanfair Level Crossing

Gaerwen

Tŷ Croes

Valley

Holyhead

Manchester to Buxton

Hazel Grove

Norbury Crossing (i)

Furness Vale

Chapel-en-le-Frith

Buxton

Wirral and Runcorn

Runcorn

Halton Junction

Frodsham Junction

Norton

Helsby Junction

Stanlow and Thornton

Ellesmere Port

Hooton

Canning Street North

Widnes to Warrington

Carterhouse Junction

Fidlers Ferry

Monks Siding

Litton’s Mill Crossing

Crosfields Crossing

Arpley Junction

Manchester Area

Diggle Junction

Denton Junction

Eccles

Heaton Norris Junction

Stockport No. 2

Stockport No. 1

Edgeley Junction No. 2

Edgeley Junction No. 1

Liverpool Area

Astley

Rainhill

Huyton

Prescot

St Helens Station

Edge Hill

Liverpool Lime Street

Allerton Junction

Speke Junction

South Cheshire

Macclesfield

Winsford

Crewe Coal Yard

Salop Goods Junction

Crewe Sorting Sidings North

Basford Hall Junction

Staffordshire

Stafford No. 5

Stafford No. 4

The Chase Line

Brereton Sidings

Hednesford

Bloxwich

Lichfield Trent Valley No. 1

Lichfield Trent Valley Junction

Alrewas

Tamworth Low Level

West Yorkshire

Batley

South Midlands

Watery Lane Shunt Frame

Narborough

Croft

Coundon Road Station

Hawkesbury Lane

Caledonian Railway

Clyde–Forth Valley to Perth

Carmuirs West Junction

Larbert Junction

Larbert North

Plean Junction

Stirling Middle

Stirling North

Dunblane

Greenloaning

Blackford

Auchterarder

Hilton Junction

Fouldubs Junction

Perth to Aberdeen

Barnhill

Errol

Longforgan

Carnoustie

Craigo

Laurencekirk

Carmont

Stonehaven

Newtonhill

Glasgow

Barrhead

Highland Railway

Stanley Junction

Dunkeld

Pitlochry

Blair Atholl

Dalwhinnie

Kingussie

Aviemore

Nairn

Forres

Elgin

This does not claim to be an all-encompassing list and there are odd stragglers that were not surveyed and are now no more.

CHAPTER 2

London and North Western Railway (LNWR)

The LNWR was one of the early creations of railway companies from a merger of three: the Grand Junction, London and Birmingham and the Manchester and Birmingham. It styled itself the ‘Premier Line’ and in the late nineteenth century was the largest joint stock company in the world. From the amalgamation it linked most of the major cities in England west of the Pennines and was the rival to the Great Northern and North Eastern for the railway equivalent of the ‘blue riband’ of the route to Scotland. It formed what is now the West Coast Main Line (WCML).

The heyday of railways is generally accepted to be before World War I and the LNWR had then a route mileage of 1,500 miles (2,400km) and employed 111,000 people. In addition to the WCML the LNWR was also acknowledged as the main route to Ireland through the port of Holyhead, and the Irish Mail is the oldest named train in the world.

In common with other major routes it has seen much modernization and automation in terms of railway signalling such that at the major centres the mechanical scene is either thin on the ground or non-existent. However, some routes in the northwest of England and North Wales and Scotland had largely escaped the worst of the cull at the time of the survey.

Whitehaven to Carlisle

Fig. 3 Cumbria and North Lancashire schematic diagram.

This section covers the remaining boxes on the former LNWR line around the Cumbrian coast and a couple of boxes in North Lancashire around the Morecambe Bay area that are no longer in service. Fig. 3 depicts a not-to-scale schematic diagram of the area and the connections to other railway companies.

The Cumbrian coast is wild and spectacular with mountains as a backdrop and yet saw intensive coal mining and iron and steel production in the nineteenth century. Many traces of the former industrial past have receded or disappeared leaving a coastline reverting to its largely unspoilt origins.

Bransty (BY)

Date Built

1899

LNWR Type or Builder

LNWR Type 4+

No. of Levers

60

Ways of Working

KT, AB

Current Status

Active

Listed (Y/N)

N

This part of the journey starts at Whitehaven, which is well known as a port and for its rugby league team. It also was the venue for the last invasion of England by John Paul Jones in 1778 during the American War of Independence.

The town has strong employment links to the Sellafield nuclear plant down the coast in Furness Railway territory.

Fig. 4 Bransty signal box, November 2006.

The box near Whitehaven station is named Bransty and was originally Bransty No. 2 – a change typical of a pared-down railway system that was once much busier. The view in Fig. 4 was taken in 2006 and was selected as a recent visit in 2014 revealed a complex of Network Rail buildings next to the box, obscuring some of the detail. The box now (2014) controls the signals of the former Parton signal box, our next stop up the line. The section of single line south towards St Bees is worked by key token and the boundary between LNWR and Furness Railways was between Whitehaven and St Bees.

Fig. 5 Overview of Whitehaven station, November 2006.

The overview of the layout is shown in Fig. 5 with the sea in attendance behind the station and box. The station looks as though it had three platforms and, by the state of the rear platform face, nearest the camera, four platforms originally. Two now remain, of which platform 1, nearest the Tesco store, is a bay platform for the shuttle service to Carlisle. Platform 2, next up and nearer the camera, is the single line from St Bees coming in from the left and going out towards Carlisle past the box on the right. It becomes double track again shortly thereafter. Platform 3 is still optimistically signed as such as if expecting track to be relaid anytime soon.

Fig. 6 Class 156 arrives at Whitehaven, December 2014.

In Fig. 6, a class 156 is arriving from Carlisle into platform 2 heading for St Bees and Barrow-in-Furness on the single line, and will require a token to proceed. The view is from the Carlisle bay and up towards the double track to Parton and Carlisle. The two home signals have anti-climb panels fitted to the ladders. The semaphore in the distance is for the down main line to Carlisle, which is on the left.

Fig. 7 Whitehaven platform 2 with token cupboard, December 2014.

The 1,283yd (1,173m) Whitehaven tunnel portal in Fig. 7 frames platform 2 at Whitehaven, and an LED colour light signal guards the way to the single track to St Bees and Barrow-in-Furness. The sharp curve on platform 2 needs not only a check rail but a flange greaser to prevent excessive wear.

Key Token

The grey box in front of the signal post is inscribed with the legend ‘TOKEN C’BOARD’ and houses the auxiliary key token instrument that enables the driver of a train bound for St Bees to help themselves, as it were. As the two token instruments here and at St Bees are electrically interlocked, only one token may be withdrawn at once, meaning only one train can proceed along a single line in the one direction. On some installations it is possible to withdraw a further token from the same instrument for a train travelling in the same direction for which a token has already been issued, but is still under full signal control. The token is the driver’s authority to proceed, and accidents have happened where a driver has been issued the token for the wrong line by a signaller. This only happened where the journey was single line in both directions. At Whitehaven the line becomes double track towards Carlisle. The token can also literally be the key, known as Annett’s key, by which ground frame points can be unlocked whilst in the section.

Bransty signal box is an endpoint for mileage calculations – it is 74 miles 73 chains (120.6km) from Carnforth station junction, while heading northwards towards Parton and Carlisle the count starts at zero.

Parton (PS)

Date Built

1879

LNWR Type or Builder

LNWR Type 4+

No. of Levers

28

Ways of Working

AB

Current Status

Demolished 2010

Listed (Y/N)

N

Parton is a real seaside village, and the station and box were on a sea wall that seems to form part of Parton’s defences. Unfortunately the box must have been under severe attack from the weather and had to be demolished in May 2010 due to its poor condition.

Fig. 8 Parton signal box, November 2006.

In Fig. 8 you can see Parton signal box is really under the cosh, with a concrete wall to protect and underpin the front of the box. The station platforms are just to the right of the box.

Fig. 9 Parton looking towards Carlisle, November 2006.

Fig. 9 is the view towards Carlisle from the down platform. The green hut building near the box is a lamp oil store – oddly in 2006 oil lamps were still in use here. Oil lamps have been replaced by electric lamps with either filaments or light-emitting diodes, LEDs. Lamps would need to be taken down once a week and filled with oil and trimmed before being replaced back up the signals posts.

Fig. 10 Parton looking towards Whitehaven, November 2006.

On the same platform as Fig. 9, the view in Fig. 10 is now looking towards Whitehaven and Barrow-in-Furness. The sea and the lighthouse emphasize the proximity of the coast to the station. The railway forms part of the sea defences for this part of the coast and a small tunnel under the railway gives access to a car park and the beach.

Parton signal box was 1 mile and 41 chains (2.4km) from Bransty signal box.

Workington Main No. 2 (WM2)

Date Built

1889

LNWR Type or Builder

LNWR Type 4+

No. of Levers

58

Ways of Working

AB

Current Status

Active

Listed (Y/N)

N

Workington lies at the mouth of one of the Rivers Derwent and there has been habitation there since Roman times.

It may seem a bit off the beaten track for heavy industry but was a centre for coal and the quarrying of high-grade iron ore. Workington, at one point, had the first large-scale steelworks in the country when all the rest were producing just iron in industrial quantities.

The steel plant that developed as a result quickly gained a reputation for high-quality steels, in particular rails for track. With the continued development of continuously welded rail in use in Britain, the plant at Workington was deemed to be not capable of producing rail to the required lengths. This facility was then transferred to Scunthorpe, after some delay. There is still a steel presence in Workington in the shape of Tata Steel, who manufacture continuous casting machines. The port is still in being and is rail connected and was originally owned by the steel company. Workington did manufacture vehicles at one point and the Pacer class 142 DMUs were made here.

The railway facilities reflected the industrial base – there were several signal boxes as well as a handsome station and steam locomotive engine sheds. The latter existed until recent years when it was dismantled for use by the Great Central preserved railway at Loughborough in Leicestershire.

Fig. 11 Workington Main No. 2 signal box, November 2006.

The first box encountered in Workington, travelling north from Parton, is No. 2. The box, in Fig. 11, is flanked by Workington freight yard just south of the box, and beyond the road overbridge even further south is the remains of the Corus Track Products works. Opposite the box was the steam locomotive depot.

Fig. 12 Site of former goods yard and engine sheds at Workington, December 2014.

Fig. 12 is looking north towards Workington station, and the former Workington yard is to the left of the main running lines. The yard still has manual point levers and a loading gauge frame on the far left that was used to check the height of loaded wagons to ensure they would fit under bridges and tunnels. The gauge frame is missing the curved metal gauge suspended from the gallows bracket.

The canopies of the station platforms can just be seen at the extreme top right of the picture. The entry to the former steam depot is visible to the right of the main running lines.

Fig. 13 Workington Main No. 2 signals, December 2014.

The view in the opposite direction is shown in Fig. 13. The up main starter colour light signal from the up platform towards Parton is signal WM2 5, and the semaphore is the starter from the reception siding that is connected to the yard behind the box. There is a crossover to enable trains leaving the reception sidings to gain the up main line. The sidings on the near left are first of all a bay platform, nearest the running line, and then carriage sidings, some part of which had been enclosed.

Fig. 14 Workington looking towards Whitehaven, December 2014.

The final view of Workington Main No. 2 and the layout is looking towards Parton and the outer home colour light signal in Fig. 14. The track plant yard is still there on the right. It was closed in August 2006. The overgrown track on the left is the headshunt for the steam locomotive depot and no doubt this would be used to shunt coal wagons to keep the locos supplied.

Workington Main No. 2 signal box is 6 miles 53 chains (10.7km) from Bransty signal box.

Workington Main No. 3 (WM3)

Date Built

1886

LNWR Type or Builder

LNWR Type 4+

No. of Levers

25

Ways of Working

AB

Current Status

Active

Listed (Y/N)

N

Workington Main No. 3 had originally been a fifty-five-lever box when the branch line to Buckhill and Calva Junction had been in operation.

Fig. 15 Workington Main No. 3 signal box, November 2006.

The box is seen in Fig. 15 at the Carlisle end of the up platform at Workington station; the two tracks in the centre are termed the middle sidings, although they were until recently loops. Note that there is still bullhead rail on the sidings.

The signal box controls not only the Carlisle end of the station and its approaches but also the reception siding down exit. The box also releases access to the ground frame for the Workington Docks line.

Fig. 16 Workington approaches from Carlisle, November 2006.

Fig. 16 shows the Workington Main No. 3 approaches from Carlisle. The subsidiary signal arm on the bracket is for the reception siding for the goods yard, accessed over the crossover. The distant signal is Workington Main No. 2’s as the boxes are so close together. A warning, in the shape of the distant signal, as to the status of No. 2’s home signal has to be given at this point to enable a train to be ready to stop if required at No. 2’s home signal. This is WM2 5, which we saw earlier. The two rods leading up to the point by the bracket signal contain one for the crossover and one for the facing point locks. The docks branch is on the left-hand side within half a mile of the home signal.

Fig. 17 Workington station, Carlisle end, November 2006.

Fig. 17 is looking back the other way towards the box and the station. The box is tucked behind the road overbridge and the middle sidings are also on view, both of which have trap points. The track on the right is the exit from the reception siding, actually a loop, with its starter signal. The trap point has a facing-point lock on it and the reception loop is also track circuited.

Fig. 18 Workington station, November 2006.

Fig. 18 is a view of Workington station and No. 3 box looking towards Carlisle. Worthy of note is how the platforms are only white-edged for about 80yd on each side, enough for a two-car unit. The canopies have been similarly cut down to fit. On the right is evidence of a train stabling facility with an inspection platform, hosepipes and floodlights. The vertical wooden battens on the end of the station building would have supported advertisement hoardings. The two middle roads would only have contained freight or passenger empty stock trains as their exits are controlled only by ground discs and they are not track circuited. The third ground disc on the right is for a reversing move over the crossover from the up main line on the right.

The two semaphores on the left are the platform starter and, on the extreme left, the reception siding starter; from the white lozenge on the front of each post, these lines are track circuited.

Fig. 19 Workington station, December 2014.

Fig. 19 is the same view as Fig. 18 but zoomed in a little and eight years later. The box has been plasticized and the middle sidings are now disconnected from the up and down running lines at the No. 3 signal box end. No one told the ground discs, though, and they are still in place. The station buildings remain well kept although the mower could use a workout.

Workington Main No. 3 signal box is 6 miles 74 chains (11.1km) from Bransty signal box.

Maryport (MS)

Date Built

1933

LNWR Type or Builder

LMS Type 11b+

No. of Levers

50

Ways of Working

AB

Current Status

Active

Listed (Y/N)

N

The original line from Carlisle was the Maryport and Carlisle Railway, before it became subsumed into the LMS in 1923. Built in 1836, it was an early and very profitable line constructed to tap the collieries’ output near Maryport and bring it to Carlisle for onward shipment. Its location meant that it had a virtual monopoly over the extensive coal traffic and this ensured success.

Fig. 20 Maryport Station signal box, November 2006.

Fig. 20 is Maryport Station signal box; the signals are plated MS but the box is officially known just as Maryport. The signals and points have been modernized and this is usual where a box has to work facilities that are some distance from it. In this case there is an opencast coal site that has a loop and siding about a mile (1.5km) from the box in the Workington direction. This would make it impractical to use mechanical equipment here. Rod- and lever-operated points can be a maximum of 450yd (410m) from the box before they need to be power operated.

Fig. 21 Maryport looking towards Workington, December 2014.

The layout at Maryport looking towards Workington and the opencast site is shown in Fig. 21. The track consists of a pair of loops that enable freight trains to bypass the single-platform station. The platform has crossovers at each end to enable passenger trains to gain the correct line. A passenger train leaving the platform shown would be signalled by MS 31 to leave via the crossover to go under the bridge on the left-hand side up running line to Workington. The elevated ‘ground disc’-replacement LED signal below the main aspect on signal 31 is for the siding whose headshunt buffer stop can be seen past the bridge.

Fig. 22 Maryport looking towards Carlisle, December 2014.

Fig. 22 shows the other direction on the single platform and the crossover access to the running lines. The incoming colour light signal just after the bridge has a ‘feather’ on it to signal a move into the platform from Carlisle. Signal MS 45 refers to the down main line towards Carlisle.

Quirkily, owing to the change of railway company ownership, the mileages change at the aforementioned headshunt buffer stops: this point is both 12 miles and 5 chains (19.4km) from Bransty signal box but also 0 miles and 0 chains on the journey to Carlisle.

Wigton (WN)

Date Built

1957

LNWR Type or Builder

BR London Midland Type 15

No. of Levers

40

Ways of Working

AB

Current Status

Active

Listed (Y/N)

N

Wigton can trace its origins back to Roman times, and the town has developed into a thriving and attractive agricultural market centre.

The major employer in the town is Innovia, who started business life as British Rayothane and had a pair of sidings behind the station, which now appear to be disused. The town has produced at least two broadcasters of note – Melvyn Bragg, now ennobled and taking the title Lord Bragg of Wigton, and Anna Ford.

Fig. 23 Wigton signal box, December 2014.

In Fig. 23 a class 156 two-car DMU hurries past Wigton signal box on its way to Carlisle. The siding leading to the British Rayothane works is on the extreme left. There is a ground frame released from the box to gain access to the siding about half a mile from the signal box.

Fig. 24 Wigton looking towards Maryport, December 2014.

Fig. 24 shows the layout from the fine station footbridge looking towards Maryport. The WN 37 signal has a chequered plate on the front that obliges any driver stopped at the signal to telephone the signal box. This requirement is often in place where the signal is not visible from the box or the track is not track circuited, but neither applies here.

Fig. 25 Wigton looking towards Carlisle, December 2014.

In Fig. 25 the view is of the platforms looking towards Carlisle. The platform on the left has a ramp in the middle of it to enable wheelchairs better train access. Part of the platform construction is different where it acts as part of the road overbridge at the end. The platform white edging does not venture this far, though.

Wigton station is 16 miles and 20 chains (26.2km) from Maryport, and control of the line now passes to Carlisle power signal box.

North Lancashire

The only two signal boxes in this region – Bare Lane and Hest Bank – were around the Morecambe Bay area.

Bare Lane (BL)

Date Built

1937

LNWR Type or Builder

LMS Type 11+

No. of Levers

32

Ways of Working

TCB, OTW, OTS

Current Status

Demolished January

2014

Listed (Y/N)

N

Bare Lane signal box controlled the branch off the West Coast Main Line that split into two to service the seaside resort of Morecambe and the ferry port (and later nuclear power station) at Heysham. The connection to Preston power box was worked track circuit block so there was no mechanical signalling here.

The box did have two types of single-line working: one train working without staff to Morecambe; and one train staff to Heysham.

Bare Lane to Morecambe – OTW

This is not a reference to trains running without people; rather the ‘staff’ is a piece of wood that acted as the authority to proceed in earlier days. The actual staff was dispensed with when track circuits came into use that denied access to another train if the branch line to Morecambe was occupied by a train.

There is a special override to enable a train to rescue another that has broken down in the OTW section but there are strict rules governing its use.

Morecambe has not fared well in terms of its rail connections and now has fairly basic facilities. It does, however, have the Midland Hotel, a splendid art deco structure opened by the LMS in 1933, which has recently been refurbished. Trains to Heysham have to first travel down the parallel single track to Morecambe, and if they are locomotive hauled, run round there before setting off for Heysham.

Bare Lane to Heysham – OTS

This way of working does involve a staff or token, and the staff can be divided into two or more sections and parts given to different trains. The parts can then be re-united into one staff, usually by screwing them together. The staff also has a metal key on the end which is used to unlock point levers at ground frames on the branch line. Staffs also bear the name of the branch line to which they relate, usually engraved on a brass plate, and redundant staffs are prized collector’s items.

Direct Rail Services operate nuclear flask trains to the power station and there is a passenger service to Heysham station itself. Although the station is advertised as Heysham Port, the ferry services appear to be freight only.

Fig. 26 Bare Lane signal box, May 2007.

Fig. 26 is Bare Lane signal box with bricked-up locking frame windows and generally uPVC’d first floor but with a wooden staircase. The box also supervised the road crossing as well as the station gardens. Originally the void beneath the platform by the box would have contained point rodding and signal wires.

Fig. 27 Bare Lane station house, May 2007.

Bare Lane station was opposite the box, and the tracks in front of the station, seen in Fig. 27, are unusual. They are two single independent lines that both go to Morecambe, but as described above, one of the tracks goes eventually to Heysham with a branch off that to the power station. It is quite common for trains to travel alongside each other in the same direction although there is no suggestion of racing.

The station building featured in the BBC TV programme Homes under the Hammer.

Hest Bank Level Crossing Frame

Date Built

1958

LNWR Type or Builder

BR London Midland Region Type 15

No. of Levers

IFS panel

Ways of Working

TCB