Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

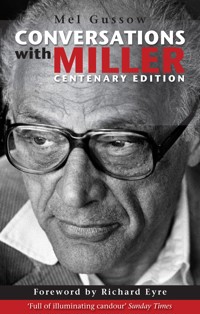

New York Times drama critic Mel Gussow first met Arthur Miller in 1963 during rehearsals of After the Fall, the play inspired by Miller's marriage to Marilyn Monroe. They then met regularly over the following forty years. Conversations with Miller records what was discussed at more than a dozen of these meetings. In the book, the author of Death of a Salesman, A View from the Bridge and The Crucible is astonishingly candid about everything from the personal to the political: his successes and disappointments in theatre, his role as an advocate of human rights, his staunch resistance to the United States Congressional witch hunts of the 1950s. He also speaks forthrightly about his relationship with Monroe. Personal, wise and often very funny, the result is a revealing self-portrait of one of the giants of twentieth-century literature, who was both a 'regular guy' and a fiercely original writer and thinker. Published to mark the centenary of Arthur Miller's birth, this new edition of Conversations of Miller features a new Foreword by Richard Eyre, former Artistic Director of the National Theatre, and an Afterword by publisher Nick Hern, in which both reflect on their own conversations with America's greatest playwright.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 362

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Mel Gussow

CONVERSATIONS

withMILLER

With a Foreword by Richard Eyreand an Afterword by Nick Hern

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Dedication

Foreword by Richard Eyre

Introduction

‘I’m rewriting Hamlet’ (21 March 2001)

‘The man up there isn’t me’ (24 October 1963)

‘It was just an image I had of this feisty little guy who was taking on the whole world’ (17 February 1984)

‘To be a playwright . . . you have to be an alligator. You have to be able to take a whack and be able to swallow bicycles and digest them’ (17 January 1986)

‘There’s nobody up here but us chickens’ (18 November 1986)

‘Some good parts for actors’ (12 December 1986)

‘The subject was right here. There was never a question in my mind about that’ (7 January 1987)

‘Tennessee felt his redemption lay in writing. I feel the same way. that’s when you’re most alive’ (9 January 1987)

‘As always, everything is at stake’ (15 January 1987)

‘You hang around long enough, you don’t melt’ (11 October 1996)

‘Anybody who smears herself with chocolate needs all the support she can get’ (1 July 1998)

‘Sometimes it takes a hundred years, and then you get it right’ (8 September 2000)

‘An unelected politician is of no significance – like an unproduced playwright’ (23 July 2001)

Afterword by Nick Hern

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright Information

For Ann

Foreword

Richard Eyre

A large part of my luck over the past twenty-five years was getting to know the playwright Arthur Miller, so when I read in newspapers the question ‘Will Arthur Miller be remembered as the man who married Marilyn Monroe?’ I felt a mixture of despair and indignation. The motives of the questioners – a mixture of prurience and envy – were, curiously enough, the same as the House Un-American Activities Committee when they summoned Arthur Miller to appear in front of their committee. I asked Arthur about it some years ago. He said: ‘I knew perfectly well why they had subpoenaed me, it was because I was engaged to Marilyn Monroe. Had I not been, they’d never have thought of me. They’d been through the writers long before and they’d never touched me. Once I became famous as her possible husband, this was a great possibility for publicity. When I got to Washington, preparing to appear before that committee, my lawyer received a message from the chairman saying that if it could be arranged that he could have a picture, a photograph taken with Marilyn, he would cancel the whole hearing. I mean, the cynicism of this thing was so total, it was asphyxiating.’

The question that lurked then – and lurks now – is this: why would the world’s sexiest woman want to go out with a writer? There are at least four good reasons I can think of:

By 1956, when he married Marilyn Monroe, Arthur Miller had written four of the best plays in the English language, two of them indelible classics that will be performed in a hundred years’ time.

He was a figure of great moral and intellectual stature, who was unafraid of taking a stand on political issues and enduring obloquy for doing so.

He was wonderful company – a great, a glorious, raconteur. I asked him once what happened on the first night of Death of a Salesman when it opened on the road in Philadelphia. He must have told the story a thousand times but he repeated it, pausing, seeming to search for half-buried details, as if it was the first time: ‘The play ended and there was a dead silence and I remember being in the back of the house with Kazan and nothing happened. The people didn’t get up either. Then one or two got up and picked up their coats. Some of them sat down again. It was chaos. Then somebody clapped and then the house fell apart and they kept applauding for God knows how long and… I remember an old man being helped up the aisle, who turned out to be Bernard Gimbel, who ran one of the biggest department-store chains in the United States who was literally unable really to navigate, they were helping him up the aisle. And it turned out that he had been swept away by the play and the next day he issued an order that no one in his stores – I don’t know, eight or ten stores all over the United States – was to be fired for being overage!’ And with this he laughed, a deep husky bass chortle, shaking his head as if the memory were as fresh as last week.

And I’ll never forget him telling me about a rehearsal of Death of a Salesman. Willy Loman was played by the great Lee J. Cobb, who was later to give a titanic performance in Elia Kazan’s film On the Waterfront. Kazan and Miller were great friends and close colleagues until Kazan named names to the House Un-American Activities Committee, preserving his Hollywood career but losing all his friends. That was yet to come.

The two men had cast Cobb as Willy Loman and late in rehearsals they were beginning to think they’d made a mistake. Cobb was very low key, barely projecting, and his characterisation was at best opaque. Then they had a run-through on stage. Somehow – and it often happens in the theatre – the writer and director’s anxiety communicated itself to the actor. Cobb knew what was at stake and pulled out all the stops and, as Arthur told me: ‘Kazan and I sat in the stalls and wept. I don’t know if it was relief or joy or the power of his performance, but it was a hell of a thing to watch.’

Miller was a deeply attractive man: tall, almost hulking, broad-shouldered, square-jawed, with the most beautiful large, strong, but tender hands. There was nothing evasive or small-minded about him. As he aged he became both more monumental but more approachable, his great body not so much bent as folded over. And if you were lucky enough to spend time with him and Inge Morath – the Magnum photographer to whom he was married for forty years after his divorce from Marilyn Monroe – you would be capsized by the warmth, wit and humanity of the pair of them.

It’s been surprising for me – and sometimes shocking – to discover that my high opinion of Arthur Miller is not held by those who consider themselves the curators of American theatre. I once heard a discussion on a US TV channel between three US theatre critics about the differences between American and British theatre. This is how it went:

First Critic: ‘Arthur Miller is celebrated there.’ Second Critic: ‘It’s Death of a Salesman, for crying out loud. He’s so cynical about American culture and American politics. The English love that.’ To which the first critic replied sagely: ‘Though Death of a Salesman was not a smash when it first opened in London.’ This feeble exchange was followed by a pained complaint from a third critic: ‘It’s also his earnestness.’

Is it ‘earnestness’ that makes Miller’s plays such a indelible part of our repertoire? It’s not a quality that I’ve noticed much in the British theatre of the last fifty years. I think it’s rather that we have the virtuous habit of treating his plays as if they were new, and find that they speak to us today not because of their supposed earnestness but because of their seriousness – that’s to say they’re about something. They have energy and poetry and wit, and an ambition to make theatre matter. What’s more, they use sinewy and passionate language with unembarrassed enthusiasm, which is always attractive to British actors and audiences weaned on Shakespeare.

In 1950, at a time when British theatre was toying with a phoney poetic drama – the plays of T.S. Eliot and Christopher Fry – there was real poetry on the American stage in the plays of Arthur Miller or, to be exact, the poetry of reality: plays about life lived on the streets of Brooklyn by working-class people foundering on the edges of gentility and resonating with metaphors of the American Dream and the American Nightmare – aspiration and desperation.

The Depression of the late twenties provided Arthur’s sentimental education: the family business was destroyed, and the family was reduced to relative poverty. I talked to him once about it as we walked in the shadow of the pillars of the Brooklyn Bridge looking out over the East River. ‘America,’ he said, ‘was promises, and the Crash was a broken promise in the deepest sense. I think the Americans in general live on the edge of a cliff, they’re waiting for the other shoe to drop. I don’t care who they are. It’s part of the vitality of the country, maybe. That they’re always working against this disaster that’s about to happen.’

He wrote with heat and heart and his work was felt in Britain like a distant and disturbing forest fire – a fire that did much to ignite British writers who followed, like John Osborne, Harold Pinter and Arnold Wesker; and later Edward Bond, David Storey and Trevor Griffiths; and later still David Edgar, Mike Leigh, David Hare. His plays continue to inspire today’s emerging playwrights and directors. Only recently the most successful play in the West End was A View from the Bridge – a play first staged sixty years ago.

What writers and directors and actors and audiences find in Miller today is a visceral power, an appeal to the senses above and below rational thought and an ambition to deal with big subjects. His plays are about the difficulty and the possibility of people – usually men – taking control of their own lives, as Miller says, ‘that moment when, in my eyes, a man differentiates himself from every other man, that moment when out of a sky full of stars he fixes on one star.’ His heroes – salesmen, dockers, policemen, farmers – all seek a sort of salvation in asserting their singularity, their self, their ‘name’.

They redeem their dignity, even if it’s by suicide. Willy Loman cries out ‘I am not a dime a dozen, I am Willy Loman…!’; Eddie Carbone in A View from the Bridge, broken and destroyed by sexual guilt and public shame, bellows: ‘I want my name’; and John Proctor in The Crucible, in refusing the calumny of condemning his fellow citizens, declaims ‘How may I live without my name? I have given you my soul; leave me my name!’ In nothing does Miller show his Americanism more than in the assertion of the right and necessity of the individual to own his own life – and, as well as that, how you reconcile the individual with society. In short, how you live your life.

If there’s a hint of the evangelist in Arthur’s writing, his message is this: there is such a thing as society and art ought to be used to change it. Though it’s hard to argue that art saves lives, feeds the hungry or sways votes, Death of a Salesman comes as close as any writer can get to art as a balm for social concern. When I saw a New York revival about fifteen years ago, I came out of the theatre behind a young girl and her dad, and she said to him, ‘Dad, that was like looking at the Grand Canyon.’

If Death of a Salesman is like the Grand Canyon then The Crucible is like the Statue of Liberty – a monument to freedom. I directed the play first in 1970 in Edinburgh and shortly after it opened I was invited to speak to the Sixth Form at Fettes College. Many years later I met one of the schoolboys. He was called Tony Blair. He told me that the play had woken him up to the latent tyranny of a repressive society and the dangers incurred in dissent. He also said that my ‘enthusiasm and evangelism’ had made him want to be an actor. Thirty years later when I directed The Crucible on Broadway I told Arthur this story. ‘He succeeded,’ he said.

My production of The Crucible on Broadway was the first since its opening in 1954, and Arthur was closely involved with rehearsals. I never got over the joy and pride of sitting beside him as this great play unfolded in front of us while he beamed and muttered: ‘It’s damned good stuff, this.’ We performed it shortly after the Patriot Act had been introduced. Everyone who saw it said it was ‘timely’. What did they mean exactly? That it was timeless.

On the opening night I sat backstage with Arthur. ‘I’m eighty-six and I’m opening a play,’ he said with rueful wonder. With Inge’s recent death, he’d taken a battering, but when he appeared on the stage at the end of the show and the audience received him and his play with unmodified rapture, he seemed to be twenty years younger. ‘At least the play’s still living,’ he said.

And it is still, even if he isn’t.

Huckleberry Finn said of the author of Tom Sawyer: ‘There are things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth.’ The same could be said of Arthur Miller, which is perhaps why it’s not a coincidence that my enthusiasm for his writing came at the same time as my discovery of the genius of Mark Twain. And it’s not a surprise that what Arthur Miller said of Mark Twain could just as well have been said about him:

‘He somehow managed – despite a steady underlying seriousness which few writers have matched – to step round the pit of self-importance and to keep his membership of the ordinary human race in the front of his mind and his writing.’

This essay was first delivered as a talk on BBC Radio 3 on 18 August 2015.

Introduction

Once when I asked Arthur Miller what he thought his legacy would be, he answered without hesitation: ‘Some good parts for actors.’ He explained that when actors and directors decide to do his plays it is not because the plays have ‘great moral importance’ or ‘even literary importance’. It is the challenge of the role, for example, the many different ways an actor could approach Willy Loman. Gradually he allowed that there was, of course, another level to the question, that there was more to be seen in the plays, that they deal ‘with essential dilemmas of what it means to be human’. Then he made it clear that they were always intended to be generic as well as specific.

As he said, he could not have written The Crucible simply because he wanted to write a play about blacklisting – or about the Salem witch hunts. The centre of the play is ‘the guilt of John Proctor and the working out of that guilt,’ and it exemplifies the ‘guilt of man in general.’ In other words, there is a moral as well as social and political base to his work, and it is that sense of morality, of conscience, that distinguishes him from other important playwrights.

Miller is one of four major American playwrights of the twentieth century, the others being Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee. O’Neill began as the pioneer experimentalist; his principal contribution was in his depiction of the disparity between reality and illusion. Williams was the great poet of our theatre, while Albee with searing intensity probes marriage, family and the failure of the American dream. Miller’s individual significance is for his moral force and his confirmed sense of justice, or, rather, his sense of correcting injustice wherever he finds it – in business, art, politics, the courts, the court of public opinion. He does this in his life as well as in his plays. Through PEN and other organizations, he has been an outspoken advocate in protecting civil liberties and helping to free dissidents – and also in fighting censorship.

His plays, especially Death of a Salesman and The Crucible, continue to speak to theatregoers around the world, in China and Russia as well as on home ground. They are unified by recurrent themes and motifs: embattled fathers and sons; fraternal love and rivalry; the price that people pay for the choices they make in life, the cost of ambition, compromise and cowardice; suicide as sacrifice; the loss of faith. Perhaps above all, the plays are about the law, in Miller’s words, as a ‘metaphor for the moral order of man.’

It is no coincidence that lawyers figure prominently as characters in almost all his plays: Alfieri in A View from the Bridge; Quentin, Miller’s surrogate and the protagonist of After the Fall; Bernard in Death of a Salesman, the young man who is arguing a case before the Supreme Court and does not need to tell Willy – or anyone – about it. Interestingly, Bernard is one of the characters that is closest to Miller himself. In a sense, Miller is lawyer as playwright, aware of all sides of a dispute but clear about where he stands: for an essential moral truth.

Were his plays only works of social consciousness, they might have faded along with the plays of Clifford Odets. In play after play, he holds man responsible for his – and for his neighbour’s – actions. Each play is a drama of accountability. Watching All My Sons, it is impossible not to be aware of contemporary parallels – of accidents in nuclear plants, of defective tyres and cars being shielded by the companies that produce them, of drug manufacturers who put products on the market before they have been adequately tested. There are other through-lines in his art, for example, the theme of power and the loss of power. In The Crucible, power rests with public opinion and the judges who run the system, but also with the individuals who first cry witch. The author is searching for an ultimate authority that will eventually rectify wrongs.

In Miller’s plays, man loses his confidence, his position, or, like John Proctor, he loses his good name. How does he behave, how will he react? Can the character gain – or regain – the courage to go on, or will he find solace in embracing defeat? Willy Loman is confronted by a loss of faith, a loss of pride and an end to possibilities. He has always thought that if he works hard and is a good salesman he will succeed, and that his sons will succeed after him. It turns out that this is a dream based on false values. For Willy, as for Miller, the Great Depression was a turning point, in itself the end of an American vision of prosperity. The second great public event in Miller’s life was the Washington witch hunt, conducted by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. This signalled the blinding of an American vision of individual freedom.

After O’Neill, the American theatre was dominated for many years by Williams and Miller. A Streetcar Named Desire in 1947 and, two years later, Death of a Salesman, were revelatory occasions, and, as we know, they are not only great plays but paradigms of two extraordinary careers, and both were directed by Elia Kazan. For Williams, his move from his home in St. Louis to New Orleans, where he found new freedoms, changed his life and inspired his art. For Miller, the University of Michigan offered a somewhat related experience. It was there in an academic environment, away from his home in New York, that he began writing plays and expanding his vision.

It would be easy to think of Williams and Miller as opposites, Williams as a hauntingly autobiographical playwright who could transform his dreams into plays that probed the human heart; Miller as more of an objectifier, a kind of American Ibsen. In Harold Clurman’s analysis, Ibsen had ‘a compelling force to combat meanness, outworn modes of thought and hypocrisy,’ and was ‘in quest of a binding unity, a dominant truth’. However, as Clurman added about Ibsen, his plays are also ‘deeply autobiographical . . . dramatizations of his emotional, spiritual, social and intellectual life,’ and it is that quality that gives his plays their ‘staying power’. All these things can be said equally about Miller.

Miller is as admiring of Strindberg as he is of Ibsen. Even as he is aware of – and offended by – Strindberg’s misogyny, there is another side to Strindberg with which Miller can identity: Strindberg’s ‘vision of the inexorability of the tragic circumstance, that once something is in motion, nothing can stop it,’ that, as with the Greeks, it is impossible to avoid the power of Fate. Miller also expresses an admiration of and a compassion for Williams. Instead of rivalry, there was a sense that the success of each fed the other and that, in tandem, they elevated Broadway. The kinship is also personal. As Miller said, ‘Tennessee felt that his redemption lay in writing. I feel the same way. That’s when you’re most alive.’

When Miller is not writing plays, he spends time building tables and other furniture. He loves carpentry and often uses it as a metaphor for playwriting: the objective is to build a better table, to write a better play. In one of our conversations, I suggested that he had already made a terrific table – Death of a Salesman – very early in his career and wondered, after that, what the incentive was. He said first of all that Death of a Salesman was his tenth play and added that each play has a different aim. A different wood? No, ‘same wood’ – the Miller wood, firm, solid, like mahogany, seemingly impervious to the weather (but perhaps not so impervious to critics). The same wood, but a ‘different aim – to create a different truth,’ and for Miller each play becomes ‘an amazing new adventure’. Some playwrights write the same play over and over again: not Miller.

As he has said, ‘I have a feeling my plays are my character and your character is your fate.’ Ineluctably, he is drawn to his study, where he writes far more intuitively than one might suppose, an artist sustained not only by his ideas but by his moments of inspiration. He also said, ‘There’s an intensification of feeling when you create a play that doesn’t exist anywhere else. It’s a way of spiritually living. There’s a pleasure there that doesn’t exist in real life – and you can be all those other people.’

Several years ago, Miller was in Valdez, Alaska to receive a playwriting award at the Last Frontier Theatre Conference. While he was there, he and a local official went fishing for salmon in Prince William Sound, which is surrounded by a glacier. As they passed an iceberg, Miller’s companion leaned over the side of the boat, chopped off pieces of ice and brought them aboard. Miller touched glacial ice. ‘Eight-million-year old ice,’ he said in astonishment. ‘It doesn’t melt.’

When I was in Valdez for that same conference a few years later, I, too, touched glacial ice – and thought about Arthur Miller. When he told me that story, I suggested that if ice can last that long, perhaps that says something about the survival of civilization and of art. Never one to sidestep a metaphor, he said, ‘You hang around long enough . . . you don’t melt.’

Miller is very much a survivor, an artist who has gone his own way without regard for fashion or expectation. There are more plays and adventures to come. The work, at its best, is both timely and timeless, which is why the plays continue to be done.

And there are also some good parts for actors.

I first met Miller in 1963, when After the Fall began rehearsals as the first production of the Lincoln Center Repertory Theatre. After that, our meetings were brief and sporadic until 1984 when I wrote a profile of Dustin Hoffman for the New York Times Magazine. At the time, Hoffman was acting in Death of a Salesman, and I followed the show from Chicago to Washington, D.C. to Broadway, speaking to Miller along the way. In 1986 I brought Miller together at the Times with Athol Fugard, David Mamet and Wallace Shawn for a panel focusing on playwrights and politics. Statements from that panel are included in this book. Late that year and into 1987, Miller and I had a series of conversations, excerpts of which were used in an article that appeared in the Arts and Leisure section of The Times. The most recent conversations have not been published before.

Occasionally, over the years I have also seen Miller in more informal circumstances. At one point, his daughter Rebecca temporarily moved into an apartment in our building in Greenwich Village, and one day, like any helpful father, Miller carried suitcases and other possessions up the staircase. One other thing must be said about him. For those who do not know him, he presents an austere, Lincolnesque image. Actually, he is down to earth and congenial; he likes to tell stories and can be wryly amusing.

At the end of October 2000 I was a participant at an eighty-fifth birthday celebration of Miller at the University of Michigan. This was an international symposium entitled ‘Arthur Miller’s America: Theatre and Culture in a Century of Change.’ Because Miller had an accident and suffered a cracked rib, he did not attend, but he did a live television interview from his home in Connecticut with Enoch Brater, the director of the symposium. There were several days of panel discussions and speeches dealing with his plays, his autobiography, Timebends, and various film and opera adaptations. Many of these events were academic but all of them revealed the intensity and the depth of the interest in his work. I spoke about Miller and his legacy in the American theatre.

After my talk, there were questions from the audience. I realized that there were several people in the house, experts on Miller, who were, coincidentally, experts on Samuel Beckett, and that I had shared many panels with them on that subject. I wondered if there was any connection between Miller and Beckett. A surprisingly lively discussion followed, as we agreed that despite their obvious disparities (of style, of subject matter) there was a certain kinship, in their political awareness and their social conscience. While Miller does not share Beckett’s pessimism, they stand on common ground in terms of their idealism. In my conversations with Miller, it has also been clear that he has gradually come around to an appreciation of Beckett’s contribution as a playwright. Miller once artfully characterized Waiting for Godot as ‘vaudeville at the edge of a cliff.’ As a writer, Miller is himself more experimental and less naturalistic than his public image.

There is another point of commonality: the two are tall, thin, stalwart, great-looking men. I don’t think either one has ever taken a bad photograph (of course, Miller has his own personal photographer, his wife Inge Morath). Beckett and Miller never met, but if they had, what would they have talked about? Women? ‘No,’ came the correct answer from the audience. Probably each would have been far too discreet (although Beckett might have been interested in knowing about Marilyn Monroe). Perhaps they would have talked about the cause of human rights, about politics, or their fondness for clowns and comedians.

In contrast to Harold Pinter and Tom Stoppard and, certainly, to Beckett – the subjects of my previous Conversation books – Miller has written widely about his own work; he also wrote his autobiography. There is no shortage of Miller commentary. What the Conversation books have in common (besides a major playwright as subject) is that each is written from a single point of view over an extended period of time and there is an arc to the conversations. With Miller, my first impression was of a man with a certain emotional detachment from his plays and the events of his life. I soon realized that he is someone passionately committed to his work and his political and social beliefs. At the same time, he has maintained an ironic perspective on his own success and a residual faith in the possibilities of the art form that he has chosen to practise.

On 11 September 2001, as terrorists attacked the World Trade Centre, Arthur Miller and his wife were in Paris. They had flown over at the invitation of the French government, cosponsors this year of Japan’s Praemium Imperiale, a $125,000 award that was to be given to Miller in October. On that morning, a friend of Ms. Morath had called them from Germany to tell them the news. Naturally they turned on the television. Two weeks later when I telephoned Miller at his home, he said about the attack, ‘I could not absorb it while it was happening. It still is incomprehensible. It’s all terrible. What can I say?’

Then he added, ‘From the news reports, it seems that the Bush administration has given up talking about a massive air strike. I have an idea. Maybe we should send over a fleet of bombers and drop 10,000 pounds of food on them’ – meaning the Afghans.

This book begins with the last of our conversations, in 2001, when Miller was past eighty-five – and then flashes back to 1963.

Mel GussowSeptember 2001

Both Arthur Miller and Mel Gussow died within months of each other in 2005.

21 March 2001

‘I’m rewritingHamlet’

On a rainy, windswept day, I met Miller at his apartment on the East Side of Manhattan and we walked several blocks to the Cinema 70 café, where he had his favourite lunch, a turkey club sandwich. The following Monday he was giving a speech at the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington, as part of a series of lectures sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities. The title of the talk was ‘On Politics and the Art of Acting’, and our conversation began with that subject.

AM: I’m going to talk about Bush, Gore, Clinton, Roosevelt and several others as performers. Roosevelt was probably the greatest performer we ever had as president. One of the best in our time was Reagan, who, without thinking about it, perfected the Stanislavsky method by making a complete fusion of his performance with his personality. He didn’t even know he was acting.

MG: Sometimes he would talk about his personal experiences and it would turn out that they would be scenes from movies in which he had acted.

AM: He couldn’t tell the difference between what happened in the movies and what he did.

MG: And he acted better as president than he ever did on screen.

AM: He was perfect for it. On the other hand, in Bush’s campaign for president, every time he approached the podium, he would give a furtive glance left and right, as though he were an impostor. What the body language tells us! There’s a story that Bobby Lewis [Robert Lewis, the director and teacher and one of the founders of the Actors Studio] used to tell. When he was a very young actor, he was an assistant to Jacob Ben-Ami, who was a famous Yiddish actor. It must have been in the late ’20s and Ben-Ami was in a play downtown [Tolstoy’s The Living Corpse]. One scene in it became the thing to see. Ben-Ami stood on the stage with a gun to his head for many minutes, trying to get up the courage to shoot himself. Finally, with the tension at its peak, he lowers the gun. He can’t do it. It was sensational, because people really thought he might blow his brains out. Bobby watched that every night from the wings. He asked Ben-Ami, ‘How do you do that?’ Ben-Ami said, ‘I can’t tell you now, because it will get out and it will ruin my performance. At the end of the run maybe I’ll tell you.’ The run ended and Bobby said, ‘Well, you promised to tell me.’ He said, ‘My problem in acting that scene is that I’m absolutely not suicidal. I can’t imagine the circumstance in which I would take my life. So how could I ever approach how this man must be feeling? I thought, where am I trying to do something, and I can’t do it? It’s when I’m about to jump into a cold shower. So what am I doing up there? I’m trying to take a shower.’ [He laughs.]

So in my speech, I say, which is the one we’re voting for: the guy who is seen with the gun to his head or the guy taking the cold shower? What I’m saying in effect is that acting comes with the territory. When you walk out of your house to face the world, you begin to act a little bit.

MG: Your point is that we all play roles?

AM: Sure. Where’s the everlasting truth? It’s only in art – when the artist approaches the paper or the canvas. Tolstoy said that we look in a work of art for a revelation of the soul of the artist. For an artist to put his soul in a work of art, he can’t act. It has to be for real. Characteristically, in all ages, the artist has the hardest time.

MG: In one of our earlier talks, you said that Tennessee Williams said his redemption lay in his art, and that you agreed with him.

AM: Absolutely. And the one good thing about growing older – or old – is that art literally is the only thing that endures out of an age. When I think of the few plays that have endured and the millions of speeches and exhortations that have disappeared. I can’t remember the authors. I can’t remember the pieces.

MG: There are a few speeches that have lasted: Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream,’ Roosevelt’s Pearl Harbour radio broadcast.

AM: That’s a form of art, though . . .

MG: And in some cases the speaker didn’t write it.

AM: Roosevelt didn’t. He had Bob Sherwood [Robert E. Sherwood] write it.

MG: A playwright.

AM: Whatever doesn’t turn into art vanishes. What have we got of Rome or Greece or Assyria – some carved stones done by sculptors, some poems scribbled on papyrus?

MG: What about the horror of the Talibans destroying those Buddhist statues?

AM: Isn’t that something! You know, the Chinese revolutionaries in the ’60s did that. They attacked temples and destroyed a lot of art in China.

MG: To take it a step further, what about societies that destroy the artist? I’m thinking of the House Un-American Activities Committee and the blacklist.

AM: The way I put it: art is civilization’s revenge on people who think the artist is just this idiot who doesn’t know how to tie his shoes. Art is the one reassurance that I have about the continuity of the human race.

MG: Does the artist have an obligation to write about political events?

AM: I can’t speak of obligations in relation to art because if the artist doesn’t naturally feel what he or she is doing, the thing is not going to work. But I have to say that the great challenges in the past were the challenges of the society’s mal-direction. Whether you look at all the Greek plays or at Shakespeare, they were very politicized stories. The most important art we’ve got comes out of such confrontations. You’re eschewing the source of great energy if you think that art is purely a conversation with yourself, which is what it became in many cases. But we’ve still got people who know this. There’s always an attempt on the part of Phil Roth or Robert Stone or Don DeLillo, a number of very good writers who are trying to grapple with this monster that we’re all being devoured by.

MG: You’re naming novelists, not playwrights.

AM: I think most of the playwrights of any seriousness know that the challenge is to bring the great beast down. Like Tony Kushner who wrote the big play that dealt with Roy Cohn, Angels in America. I’m sure he’s still at it. He’s devoted to that kind of reality.

MG: That’s one thing that keeps you going as a writer.

AM: Yes. Trying to bring order to this chaos, which is next to impossible.

MG: How is your new play going?

AM: I’ve got two of them I’m working on at the same time. One of them is half finished.

MG: Resurrection Blues?

AM: I wrote one version of it, but I want to look at it again. I let it lie for a while. There’s something not right about it. There’s wonderful stuff in it. The form of it is cracked somewhere.

MG: Cracked?

AM: Split, somehow. It’s a good cartoon for the play, in painting terms. I’ve got to change some of the colours in it.

MG: What’s the other play?

AM: The other play is about an old man, not me, who is nearly blind. He’s pursued by his life and he’s trying to get out of it. It keeps tackling him again and again.

MG: Trying to get out of it by suicide?

AM: No, no, not suicide, not at all. He’s trying to outlive it. It’s got a lot of different scenes, but it’s basically taking place in a house out in the country.

MG: And it’s not about you.

AM: I couldn’t be the way this guy is. He’s a former builder of tract houses, a hundred houses at a time. The usual businessman whose desire was to be a poet, or an actor. I think I’ll be able to finish that play soon.

MG: I just read The Man Who Had All the Luck [which failed on Broadway, in 1944].

AM: They’re doing it in Williamstown this summer. Scott Ellis is directing it. They did a reading at the Roundabout Theatre down on 23rd Street. I said, I’m not sure the damn thing is going to work. They cast it gorgeously. Then Scott said, ‘Can I do it in Williamstown?’ I said, ‘Certainly – with these people.’ They’re all excited about it. There really is nothing like it, for good or ill. It’s basically the story of a young man, who for reasons he could never put his finger on, always succeeds. The point comes where he becomes more and more certain that anything he’s managed to accumulate, including his family, will be struck down by retribution from some source.

MG: Was that something you felt at the time?

AM: That was based on someone I knew about in the middle west, a man who hung himself. He couldn’t stand the tension. I guess it reflected the fact I already had a great levelling instinct.

MG: What do you mean by levelling instinct?

AM: That no one, including me, should ever regard himself or be regarded as being more important than anybody else, nor be paid more or be given more homage.

MG: The original story was told to you by your first wife’s mother?

AM: Yes. I knew the wife in the story slightly. I never met the man. He was dead by that time. It was my interpretation of what had happened to him. At an extremely young age he was a very successful businessman.

He ended up owning a half dozen different businesses and became paranoid. He couldn’t have been more than twenty-seven, twenty-eight years old. He was certain that he would be robbed, that people were going to set fire to various things. He was a farmer, among other things, and he ended up hanging himself in his barn.

MG: That’s not how the play ends.

AM: I had not written it with the kind of total darkness that it would require. I couldn’t hang him with this play. In any case, he came very close to saving himself, and had he had a little better help he might have survived it. I never believed in the end of that play. Years ago, I rewrote the last three or four pages. I couldn’t find the requisite kind of ambiguity that was necessary because it’s an impossible philosophical situation. The play is basically trying to weigh how much of our lives is a result of our character and how much is a result of our destiny. There’s no possibility for me to come down on one side or the other. And I was not able to until I reread it again. I didn’t want it done with the other ending.

MG: You’ve said that the play is ‘the obverse of the Book of Job.’ The central character believes that man experiences at least one bad thing in his life – and he keeps waiting for that one thing to happen.

AM: That’s right. He’s waiting for that blow. Subsequently I thought that a lot of people feel that way.

MG: You don’t feel that way, do you?

AM: I used to, more than now.

MG: After you first began to succeed?

AM: Even earlier. Everybody I knew had faced a calamity, and some had survived it and some hadn’t. The idea was that no one could go through life unscarred.

MG: This is one of the themes of Albee’s The Play about the Baby, that man has to experience tragedy in order to be human.

AM: I haven’t seen the play yet, but I think there’s truth in that.

MG: Have you faced your calamity?

AM: [Laugh] Eight or ten times! I came to the edge of life a number of times, once with the House Un-American Activities Committee. Then with my divorce. I was married seventeen years. That was a big blow, that I would come to that.

MG: And Marilyn too?

AM: Marilyn. After all, we were married for five years [1956-1961]. She never lived that many years with anybody else because nobody could hang in there that long. I wasn’t writing anything in those days. I would call it a calamity – to me. It was for her, too, I suppose, but she was more accustomed to it. Her life as a whole was full of calamity.

MG: The woman who had no luck – even though she became a movie star.

AM: That whole story of the movie star and the way it consumes people – it’s so banal by now. And it gets repeated again and again and again. You pick up a paper and this loving couple are suddenly at each other’s throats.

It’s the oldest story. Success is the great man-eater. Surviving it is as hard as attaining it, if not harder. Early on I fastened my arm to the idea of the theatre, specifically tragic theatre, as a root that goes back to the beginning of time. By attaching myself to it, I felt safe. I could always revert to it, in worse times. Maybe I could add to it somehow.

MG: If you hadn’t found that?

AM: I don’t know what would have happened.

MG: After The Man Who Had All the Luck failed, you were thinking of doing something else, like writing fiction.

AM: Yes. The play closed in four days and was totally unremarked. I promptly said, I don’t belong in this and I wrote a novel, Focus, to start off my career as a novelist. The idea of spending all that time – and hope – on something that could be wiped out in a matter of days. By the way, Focus