Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

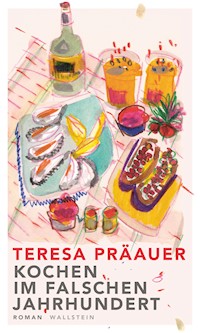

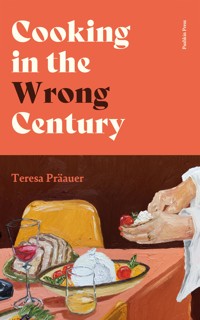

'Brilliantly clever' Irish Times 'Thoroughly enjoyable' Ayşegül Savas An evening of perfect preparation. A night of uninvited chaos. For the hostess, food has always been about growing up. From the pancakes your grandmother made you, dolloped with jam, to the salty glug of your first oyster. Now, poised at the brink of midlife, the hostess prepares for a dinner party in her new apartment. With a hunger for the finer things in life, she folds linen napkins into neat triangles, arranges wildflowers for the table and puts on a jazz playlist the projects effortless cool. But her composure begins to falter when her guests arrive drunk and late, downing bottles of her perfectly cooled wine and trailing water over the floor. Here comes the chain-smoking professor who never says the right thing, the husband glued to his smartphone, the wife who makes a secret pass at your boyfriend. As small talk and social preening give way to sexual tension and lost inhibitions, the hostess struggles to maintain control over an evening far beyond her wildest imaginings. __________ 'Very funny, very stylish and very moving' Adam Thirlwell'Irresistible' New Statesman 'Clever, amusing' Daily Mail 'Astute, witty and as pleasure as a case of Crémant' Claire Powell 'Beautiful writing' Stylist

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 171

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1‘Cooking in the Wrong Century is very funny, very stylish and very moving. Teresa Präauer is a novelist of unusual elegance and charm — who can make the reader sadly aware of time passing even while leaving them delightedly hungry’

Adam Thirlwell, author of The Future Future

‘Deliciously unsettling and thoroughly enjoyable. It’s so much fun to see this meticulously planned dinner party go wrong’

Ayşegül Savaş, author of The Anthropologists

‘Astutely analyses social interaction and presents it in a humorous and ironic way’

Vogue Germany

‘Präauer is one of the brightest candles on the cake of contemporary German literature … breathtakingly funny, comical and very, very insightful’

MDR’s Best New Books

‘With her well-seasoned, original menu Teresa Präauer proves herself to be an amusingly sophisticated hostess and stimulating companion at this literary dinner’

Wiener Zeitung2

3

4

Cooking in the Wrong Century

Teresa Präauer

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BY ELEANOR UPDEGRAFF

PUSHKIN PRESS

Contents

Cooking in the Wrong Century

6

7Do you remember that first time, deciding to cook something in your very own flat—it wasn’t much more than a room—and realizing only halfway through that you were going to have to run out and buy salt? You didn’t even own a salt cellar. So many things to think of in adult life! Your first salt—how would it taste?

How much at the beginning of things you were. Your first cup of coffee—back then with lots of sugar. First Chinese meal with friends. Your sister made a bet that she could put a teaspoon of red chilli powder in her mouth and swallow it down in one. Your first boyfriend, your first capricciosa with artichokes. Neither of you liked the taste of the red wine. You were so young; you’d have preferred Coca-Cola.

Your first whole cooked artichoke. In Rome—where else? In a tiny kitchen which you had to share with strangers. Living together wasn’t pleasant, in the end, but at the beginning it very much was.

In the beginning was the artichoke. And, on the table in front of you, a bowl containing salt, pepper, lemon and olive oil. Leaf by leaf, you pulled the big bud apart, working from the outside in, until you reached the core, the delicious artichoke heart and the so-called choke from which you should have removed the hair. It tickled and stung when you sank 8your teeth into it. That sweet bitterness! Afterwards, you licked the oil and lemon from your fingers.

Your first oyster? Late—you were already in your mid-thirties. Watched the others as they pressed the chalky shells to their lips and let the live, slimy things slip into their mouths along with a swig of saltwater from the Pacific. You simply copied them. You hadn’t become accustomed to anything in your life, were hungry for each and every new flavour. The air was cold, the sun just on the point of setting, the light all pink and blue. That kind of thing can’t be planned, nor can it ever be repeated. Someone in the group had ordered a bottle of Sancerre; you were standing outside at Seattle’s famous Pike Place Market. The evening was beautiful, and none of it to be taken for granted.

That first salt? Sure, it tasted salty, the hostess exclaimed, and she laughed.

9250g flour

125g butter

1 egg

10It began like any one of those evenings on which you’ve invited people round. The oven was preheated, salad ready in the fridge, only lacking its oil and vinegar; bowls of nuts and salted crackers were clustered on the table. Small dishes had been arranged on large, heavy plates, napkins folded beside them and cutlery in the correct position: knife to the right, fork to the left. Or both on the right-hand side? The hostess cocked her head and considered. Did they need spoons? She hurried from dining room to kitchen. The air was thick, indeed, with anticipation and excitement. Voices reached the room from the street outside, young people in high spirits on the way out, walkers with their dogs, a skateboard rolling along the tarmac, the cross-city train passing close by. Otherwise it was still, the way only summer evenings can be still.

Their guests were a couple—now a married couple—with whom they were on close terms, and a friend from Switzerland who had lived here in the city for many years and was this evening appropriately tardy for an academic, for whom a quarter-hour’s lateness was considered standard. Each had brought a bottle of wine, and they wiped their feet dutifully at the door and cast wordless glances at the wet soles of their shoes by way of enquiring whether they could keep them on. The hostess nodded; generosity and 11nonchalance were the order of the evening. Everyone ought to feel comfortable. Her partner had taken their guests’ jackets and arranged them on hangers on the coat stand in the hall. Barefoot, the hostess preceded them all into the dining room.

Jazz was playing in the background. On demand, they could find out what it was. Sixties? Wayne Shorter or John Coltrane? The talk was of records, even if they were listening to music via a digital streaming service, which had automatically taken over responsibility for the track selection and always played exactly what suited the current mood. The playlist collated jazz for jazz lovers with little knowledge and plenty of taste.

From the dining room, a narrow, doorless passageway led through to the kitchen. The wife, now also barefoot, padded along after the hostess; the husband raised his hands apologetically and kept his moccasins on. Part of the outfit, he said with a laugh. The shoes seemed—like everything else he was wearing—tinged with irony, yet still elegant. He’d thought about fashion once or twice in his life, but it had never become a passion.

They opened a bottle of crémant, raised their glasses, stayed standing in the kitchen and, not having seen or spoken to one another over the last few weeks, talked about all that had happened. Good things and incidental ones. The friendly hostess wore a sleeveless black jumpsuit and had her hair pinned up. A cotton apron, green and blue striped, was knotted at the back of her neck and tied round her waist. To a lovely evening, said the husband to the hostess, then turned his gaze to the wife and finally the hostess’s partner as they all awaited the arrival of the Swiss man, who even 12now was standing in the stairwell. All four, glasses in hand, trooped back from kitchen to dining room and through the hallway to the door. Big hug, three kisses; in Switzerland, it was never two.

And now, back to the kitchen! A fifth glass needed to be taken down from the shelf. Is that Finnish? The glass? Iittala, said the hostess. Cheers, answered the guests. Lovely you’re here. The hostess choked in the middle of the sentence; her partner smacked her on the back with the flat of his hand to free up her airway. Cheers!

The hostess didn’t just like listening to jazz, but also pop, classical and New Music. John Cage, prescribing nothing but silence for the duration of four minutes and thirty-three seconds. Mid-century New York avant-garde—why not? If nothing else, the horoscope she’d read online had predicted true curiosity paired with high tolerance for her day, week, life. Pisces also had a tendency to vulnerability, to daydreaming and to critical thinking. Then again, Pisces didn’t believe in star signs.

The wooden board on which vegetables had earlier been chopped was leant across the sink, the large kitchen knife drying in a stainless-steel container. The wife wasn’t taking part in the conversation but instead staring out of the window. In the building opposite, two policemen were also standing by the window, smoking cigarettes. Had they by any chance just waved at the wife? When the attentive hostess tried to bring the wife back into the conversation, she started and at long last turned to the group. So, all together once more! The wife laughed and apologized, namely for her lack of attention. Like my students, cried the Swiss man boisterously. 13The wife looked at him and shook her head, but was still willing to laugh along. It was a long time ago now that she had been a student.

Conversation was made. Cheers, again—to a lovely evening, exclaimed the hostess. She didn’t seem to mind repeating gestures and sentences, provided they served the collective ritual. The Dave Brubeck Quartet played ‘Take Five’. Shall we sit down, asked the hostess’s partner.

141 onion

1 leek

150g bacon

15Was that really how things were? Or was it—much more likely—that the couple with whom they were friends had, once again, arrived too late? Not just by the few minutes generally considered polite, but by more than half an hour? And that, on the other hand, their Swiss friend had showed up bang on time? In private, the hostess and her partner didn’t stop themselves from drawing comparisons with the precision of a watch mechanism.

When the door was opened for their guest, however, he made no move to ask whether he could borrow some house slippers, but instead came in confidently, handed over the wine and headed straight for the dining room. He sat down and reached for the nuts. He was hungry; he’d done nothing all day but conduct exams. Something smells good, he exclaimed, moving the crackers to his side of the table and stuffing them rapidly into his mouth, one by one.

The hostess remained on her feet and opened a bottle of crémant. From Alsace, of course. She cast a critical eye—which was not intended to escape the Swiss man’s notice—over the lavender-coloured label and filled their glasses. Then she too sat down at the table, smoothed her apron and immediately loosened its strings. She drew up one foot to the seat of her chair, inclined her head and listened as her partner and the Swiss friend, who hadn’t known each other 16long, made conversation. The hostess sat there as though in a painting, consciously posed: SittingWomanwithLegsDrawnUp, completely the wrong century. Beautiful view, enthused the Swiss man. The hostess’s eyes travelled down to her apron. The combination of elegant jumpsuit and practical cooking garb promised a sensory evening. The Swiss man, who had been talking about the building opposite, let out a laugh. You too!

On the other side of the street, as seen from the dining room, was one of the so-called National Police Force Headquarters, an imposing structure built in fin-de-siècle style, with white-painted bars in front of the windows. The hostess’s apartment was on the top floor of an old-fashioned block of flats, the kind that was so common in this city’s bourgeois areas. A slender French balcony, barely usable, looked out on to the street; if one were to open the door at the back of the bathroom, a second small balcony, on the opposite side of the apartment, offered a view of the courtyard. A net had been strung above the courtyard at roughly roof height to stop the pigeons from taking up residence.

The sky that evening was almost cloudless. It was still light outside; soon it would be twilight. The hostess stood up to fetch candles from the kitchen and put them on the table. The candlesticks were antique finds, made of brass and silver. She lit the candles and sat down. Wax melted and dripped on to the new Danish dining table. The hostess practised composure in the face of the dripping wax, allowed the drops to harden, didn’t pick them off. A dining table should tell stories of life lived, after all.17

All three toasted each other effusively and drank the crémant while waiting for the couple who were late. At some point, everyone in their group of friends had stopped drinking either champagne or Sekt and, even if one sparkling wine was very much like another, now only ever drank crémant. The wine they bought was more expensive than it used to be, back when they’d compared price labels at the supermarket in order to save a few cents. The crémant, by contrast, was paid for now with large notes or a card.

Cheers! They began to relate what had been happening recently. Talk turned to matters that needed sorting out before the summer, and to the ostensible passivity of today’s students, especially—the Swiss man explained in detail—with regard to undependently interstanding a set that’s been tasked them! He coughed, having jumbled his words, and started again. Independently understanding a task that’s been stet them! They all laughed. She had been very independent as a student, the hostess said assertively. The Swiss man laughed and coughed simultaneously. A task that’s been set them, he cried; now he’d finally got it out. Whack him on the back, the hostess prompted her partner. He hesitated. The Swiss man waved it off.

She was one of the first in her family to go to university, the hostess said. A creative wrong answer—the Swiss man continued his monologue, refusing to be interrupted—was, for him, infinitely preferable to all this uncritical parroting of the syllabus. Creative, repeated the hostess, as though she had bitten into a raw onion. This was not going to be an evening on which she merely listened. In the sense of making something, said her partner, in the tone of a polite mediator. 18With their own ideas about the world, cried the Swiss man, and threw up his arms dramatically. This made him look like a class warrior. His arms instantly fell again, his fingers reaching for more crackers.

He wore a dark T-shirt, cargo shorts and practical sandals. A single lock of hair had just escaped the rest and was now bobbing daringly around at the crown of his head. As a young man, he had formed his own ideas about the world by reading the global section of a well-known Swiss daily. You couldn’t read that paper any more now, for reasons they all knew. The hostess’s partner said he only ever read the Guardianand the NewYorkTimes. Primarily the crosswords and recipes for burnt cauliflower.

There are no more utopias, the Swiss man exclaimed, rather too loudly and despairingly, and he snatched the final cracker from the first bowl. It sounded as though this had been said a couple of times too often. He didn’t seem to mind repeating gestures and sentences, provided they served to corroborate his opinions. Miles Davis played ‘So What’. Another glass of crémant would imply that further monologues were encouraged. The hostess didn’t want to be a view. When on earth would the other guests arrive?

Where would their Swiss friend be spending his well-earned holiday, then—the hostess’s partner tried to change the subject and steer the conversation in a less culturally pessimistic direction. And did he already have plans for the autumn? Nothing but exams, said the Swiss man, who continued to lament the coming academic year, an academic year devoid of utopias.19

Her parents had never had a copy of the Brockhausencyclopedia on their shelves, the hostess began again. And yet, with the advent of the internet and subsequent discontinuation of printed encyclopedia sales, they’d no doubt have gone out and got hold of an incomplete edition in a second-hand bookshop. Now the hostess’s partner laughed—somewhat too loudly, given that the hostess hadn’t in fact told a joke.

204cl Campari

4cl vermouth rosso

21Things had, by this time, become rather cheerful. Two bowls of nuts and crackers had been consumed; the salad had stayed in the fridge. It could be taken out of its Tupperware now and transferred to the big ceramic bowl, the hostess said.

The Tupperware didn’t fit with the nonchalance that new cookbooks promoted with their photography. For cooking, one wore washed-out linen shirts, wide-legged jeans and turbans fashioned from brightly coloured scarves; one was pictured in front of quinces, lemons and aubergines, beside thick bunches of herbs. None of the preparation ever consisted of sweating over a full trolley in the queue at the supermarket checkout; instead, one took one’s time and went to the market or bazaar. There, the stallholders were known by name, wares were tested by handling them. One would sample preserved olives, dried mulberries and Corsican cheese.

Need any help? asked the Swiss man. It didn’t sound as though he particularly wanted to offer that help. Don’t get up! The vinaigrette of mustard, olive oil and vinegar was already mixed. The hostess had allowed the preheated oven to cool down again a little, its door closed. A quiche could wait; that was the practical thing about it. A classic Swiss recipe, their Swiss friend called from the dining room in the direction of the kitchen, following it up with a deep inhalation which clearly aimed to capture the aroma of 22freshly baked quiche—while the quiche remained, alas, as yet unbaked.

The Swiss man had made himself comfortable. Under the table he had divested himself of his footwear after all, and a pair of ankle socks labelled ‘Sport’ had emerged. Of course, you two don’t smoke any more, he said, and stayed in his seat. They had moved on seamlessly from pre-summer-holiday thesis-marking to the modern jazz quartet. Bach’s ‘Air’ was playing, and they’d got into the swing of conversation. The word record had been dropped in again a couple of times, in connection with various dates and the unavoidable mention of the composer’s name. Bach, the hostess had been moved to call out. Bach! Bach still had utopias, the Swiss man had declaimed. He also still believed in God, the hostess’s partner had replied.

They had then talked about going out—the kind of going out they didn’t do any more, not like when they were younger. It was only fun if you were single, the Swiss man had stated. Whereupon the hostess had asked, Where are all the women in jazz, anyway? On the contrary, the hostess’s partner had disagreed with the Swiss man, there was more going out these days, namely to the better bars, where they had better drinks and live jazz. The hostess’s partner began rhapsodizing about cocktails and drummed his fingers on the tabletop. The Cuba Libres in that American bar in the city centre, he cried. In his enthusiasm he cut, as he so often did, a generous and optimistic figure. His parents had most certainly had an encyclopedia on their shelves, but he’d never read as far as the entry for Approach-Avoidance Conflict. Life hadn’t given him half-measures, and he didn’t do half-measures in 23life—after all, it did have to be mutual. He was able to get simultaneously excited about a free Cuba and the American Way of Life.

During the entire conversation, the Swiss man had been fiddling with a yellow cigarette packet—Parisienne brand. Written on it in German, French and Italian were warnings that smoking was lethal. Here, intra-European understanding was working. The hostess’s partner’s left thigh bounced up and down in time with the music. He’d pulled out his smartphone from his trouser pocket and looked up a list of female jazz musicians online. Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday. The list was too long to name them all, and these were only the most famous ones. But all dead, mortes, perdues, cried the Swiss man. Look for jazz musicians, female, twenty-first century, the hostess instructed her partner, who tapped in the new search terms. The hostess had been in a relationship with her partner for a couple of years, and he in turn was in a relationship with his smartphone. The Swiss man had a girlfriend, but was also fine on his own. He absolutely couldn’t stand cocktails, he repeated, in appreciation of the crémant from Alsace, and raised his glass. Santé!

By the time the delayed guests finally rang the bell, the waiting trio had already polished off the first bottle of crémant. The hostess got to her feet, the hostess’s partner and his smartphone followed her, the Swiss man brought up the rear. The door was opened for the married couple.

Ah, there you are!