22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Crowood Theatre Companions

- Sprache: Englisch

Costume Design for Performance offers a detailed insight into the creative process behind designing costumes for the performing arts, including theatre, opera, dance and film. Guiding the reader through the essential steps of the designing process, Bettina John combines extensive knowledge of the industry with insights gleaned from leading experts in the performing arts. Featuring over 200 original artworks by more than thirty designers, this book gives a rare insight into this highly individual and creative process. Topics covered include script analysis; in-depth research techniques; practical techniques to explore design; basic drawing techniques; character development; the role of the costume designer and wider team and finally, advice on portfolio presentation.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 356

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Costume design by costume designer and maker Sophie Ruth Donaldson for Rubby Sucky Forge (2020, by Eve Stainton with Joseph Funnel and Gaby Agis), photograph by Anne Tetzlaff.

First published in 2021 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© Bettina John 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 928 0

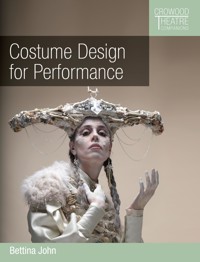

Front cover image: Costume design and make by set and costume designer Bettina John for ‘Broken Dreams’ (2019, Belinda Evangelica) (Headpiece and beadwork by Anna Kompaniets).

Cover design by Maggie Mellett

CONTENTS

PREFACE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

1 TEXT AND RESEARCH

2 PRACTICAL TECHNIQUES FOR EXPLORING DESIGN

3 FUNDAMENTAL DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

4 ON CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

5 THE ROLE OF THE COSTUME DESIGNER

6 THE COSTUME PRODUCTION PROCESS

7 HOW TO BREAK INTO THE INDUSTRY AND SURVIVE

RESOURCES

INDEX

PREFACE

Since embarking on the writing of this book one year ago, I have discovered far more about costume than I could ever have imagined. I knew from the outset that I wanted to include as many voices from my community as possible, but I never dreamed that I would get the chance to speak to so many professionals and receive this extent of valuable insight. The generosity I experienced is exemplary of the industry and the people who work within it. It is a creative community that offers a place to everybody who shows the necessary commitment and passion. The industry welcomed me in after I had graduated from a fashion design degree course and gave me a platform to express myself, while earning a living. Granted, establishing myself as a designer entailed an enormous amount of work, but truly creative work is seldom easy. I have thoroughly enjoyed the journey from graduation to where I am today, despite the bumps and hurdles along the way. I have always continued to learn and gain further qualifications, including a Master’s degree in Theatre Design, a series of short courses and a lot of on-the-job training in professional, yet welcoming environments. Several professionals helped me throughout this journey and without them I could not have developed into the designer I am now.

My aim is that this book reflects the community to which I belong, rather than acting as a response to literature on the subjects touched on within the book. I have personally worked predominantly in costume design for theatre, opera and dance; but I wanted to include some of the parallels and departures from film. I interviewed and consulted numerous professionals to get a good grasp of how the theatre and film industries function today. In combination with my own experience working as a costume designer, I was confident that I could assemble a useful and informative introduction to the process of designing costume for performance. However, writing a compact introduction to such a vast field as costume turned out to be a bigger challenge than I imagined.

‘PING’ (2014, costume and concept: Daphne Karstens; performer: Lorraine Smith; choreographer: Angela Woodhouse; lighting designer: Neil Brinkworth; sound designer: Nik Kennedy; make-up and hair: Goshka Topolska; photographer: Alex Traylen)

The drawings and documents included in this book are contributions by a variety of designers and artists from the United Kingdom, Germany, France, The Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, the USA, Brazil, Russia, Greece and Australia. They allow the reader an exclusive insight into an otherwise rather private process. It allows the reader a deeper understanding of the design process and it underlines the uniqueness of each and every designer and their methodology. In the process of finding contributors and carrying out interviews for this book, I became increasingly aware of this. I tested some of the ideas for the book with a group of costume professionals online, only to realize that each costume professional has their own unique perspective on the industry and that there is no single correct interpretation. Every conversation I had confirmed this, while also indicating that there is still a substantial amount of overlap and similarities. These shared methods and understandings that most professionals were able to agree on, filtered through my own experience and have formed the basis of this book.

An introduction into the world of costume can only touch the surface of the various aspects that costume encompasses. Each aspect deserves its own discourse, but this is, sadly, not possible within a single publication. I must admit, I got regularly carried away conversing with other professionals, only to realize that I had to reduce hour-long conversations into short, poignant paragraphs. I encourage the reader to use this book as an entry point and to continue reading about this wonderful field and the specific aspects that interest them.

My work as a designer has allowed me to travel and see a variety of approaches to theatre-making. It has allowed me insights into the industry as it operates in various other countries, such as Germany, the USA, Brazil and Russia. However, this book is written from the perspective of the industry in the United Kingdom. Many similarities, but also some differences, exist between the industry here and in other Western European countries and the United States, particularly with regard to the infrastructure, such as costume roles, the unions and fees. However, the design process itself is always more dependent on the individual designer rather than the country in which they operate. As such, the advice given in this book, and the suggestions made, could be helpful to any aspiring costume designer, no matter where they are located on the globe.

My hope is to inspire early career designers and those that aspire to becoming designers within the theatre and film industry. I hope to offer students and graduates advice on how to become better designers and how to progress within the industry. I hope to answer many of the questions that I receive regularly from my students. I hope to give tutors and teachers a solid handbook that they can rely on when discussing costume as part of their curriculum. I hope to give all costume enthusiasts an insight into the world of costume. Above all, I hope to represent this industry in the best possible way.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CONTRIBUTORS AND INTERVIEWEES

Anna Kompaniets | Artist | Designer

Cher Potter | Designer | Researcher | Curator

Chiara Stephenson | Stage and costume designer

Christopher Oram | Set and costume designer

Clemens Leander | Costume designer and supervisor

Daphne Karstens | Wearable sculpture artist

Dione Occhipinti | Fashion stylist

E. Mallin Parry | Set and costume designer | Researcher

Fiona Watts | Scenographer

Florence Meredith | Costume designer and maker

Frances Morris | Costume designer and maker

Henriette Hübschmann | Set and costume designer

Hannah Calascione | Theatre director

Jerome Bourdin | Set and costume designer

Julia Burbach | Opera director

Julia Schnittger | Set and costume designer

Laura Iochins Grisci | Designer

Louise Gray | Multi-disciplinary designer

Lex Wood | Costume designer for film | assistant costume designer for film

Michael Grandage | Theatre director and producer

Matthew Xia | Theatre director

Nadia Lakhani | Designer and Linbury Prize Mentor

Natasha Mackmurdie | Costume supervisor

Neil Barry Moss | Director and costume designer

Noémie Laffargue | Costume designer

Phillip Boutté Jr | Concept artist

Sophie Ruth Donaldson | Costume designer and maker

Takis | Set and costume designer

Yann Seabra | Set and costume designer

IMAGE CONTRIBUTORS

Adam Nee | Set and costume designer

Bek Palmer | Set and costume designer

Brad Caleb Lee | Visual dramaturge | Designer

Brenda Mejia | Costume designer

Elizabeth Real | Costume designer and maker

English National Opera costume department

Eva Buryakovsky | Costume Designer

Evelien Van Camp | Costume designer and maker

Frankie Bradshaw | Theatre designer

Jason Southgate | Set and costume designer

Jody Broom | Student of the UAL Costume Design for Performance short course 2020

Jocquillin Shaunté Nayoan | Fashion Illustrator and Costume Designer

Laura Belzin | Fashion designer

Maryna Gradnova | Costume designer

Megan Stilwell | Costume designer and maker

Nicky Shaw | Set and costume designer

Paulina Knol | Costume designer

Rebeca Tejedor Duran | Costume designer

Sarah Bottomley | Costume designer

Stephanie Overs | Designer

Viola Borsos | Costume designer

Ysa Dora Abba | Designer

INTRODUCTION

WHY WORK IN COSTUME?

The world of costume is vast and offers endless opportunities for creative people and artists to express themselves and to work collaboratively within small, medium and large teams. The world of costume offers anybody interested in the field a place. It allows an aspiring costume professional to carve out a highly personal career and work in exactly the way they desire. This can be challenging, but it is absolutely possible, and thousands of costume professionals have achieved just this. The most important question an aspiring costume designer needs to ask themselves is why they want to be one, what sort of projects they want to be involved in and what sort of designer they want to be. A strong sense of purpose and the right work with a message the costume designer really cares about will get them through the more challenging times, which most certainly need to be expected when entering this industry. Once having found the right place within this world, it is one of the most rewarding, most enjoyable and most exciting professions or occupations there is. The sheer number of options available to a costume professional is astounding, as well as overwhelming at times. This book will give a thorough, yet clear insight into the different pathways available to an aspiring costume professional in general, while focusing on the role of the costume designer in particular.

Costume design and make by set and costume designer Bettina John for The TruePop Manifesto (2014, Belinda Evangelica).

WHO IS THIS BOOK FOR?

This book is an introduction to the world of costume and the role of the costume designer for anybody interested in the field and profession. It can act as a sourcebook for an aspiring costume designer, somebody training to become a costume professional, studying on a degree, short course or, indeed, on their own terms, or considering training. While giving concrete examples and detailed descriptions of various scenarios and processes, this book went through a rigorous editing process, with the aim to remain as clear and simple as possible, while not taking away from the complexity of the field of costume. Topics are covered from the perspective of the role of the costume designer, resulting in a reduced coverage of the work of other costume roles and aspects, which all deserve their own book. With the focus on the design process and how to become a good designer and sustain a career as a designer, this book will be useful for people from around the world. However, some information found in this book is specific to the United Kingdom and will, therefore, be particularly useful for aspiring designers wanting to work in the United Kingdom or places operating in a similar way.

WHY WRITE A BOOK LIKE THIS?

The role of the costume designer has undergone many changes over the decades of its existence and is not quite what it used to be when it started to develop in the middle of the twentieth century. The role of the costume designer grew out of a team initially less focused on design and more on providing a show with costumes and looking after them. Since then, this team has undergone fundamental changes and seen the development of numerous other costume roles and specializations. While those changes have been for the better, there is still a lot of work to do. Many people, and even some theatre professionals themselves, do not have a full understanding of the role of the costume designer and the costume team. The costume team, as well as the costumes, do not always get the credit and appreciation they deserve. Often costume professionals are still not paid as well as other roles within a production. This book will attempt to contribute to a better understanding of the field of costume and its communication. Furthermore, beyond the practical and functional content relating to costume and the costume designer, this book wants to open up the reader to the potential of the costume to have agency and the possibilities available to the costume practitioner.

APPROACH TO THE BOOK

This book is based on first-hand experience and numerous conversations with professionals from the theatre and film industries. The premise of this book is to represent these industries as they exist today and make information accessible to aspiring costume professionals, information that otherwise would not be as easily obtainable. It cannot be stressed enough, how many perspectives and approaches there exist within this field, which this book attempts to take into account. To remain compact and accessible, this book gives just enough detail to grasp the complexity of costume and the work of the costume designer. For the interested reader, there are many more books to read and more subjects to study. A list of further reading suggestions can be found at the end of this book.

While costume design can exist outside the boundaries of text, this book focuses on costume design for text-based theatre. Chapter 1, therefore, introduces methods to analyse a script and then seamlessly leads into an introduction to research methods. However, most methods and tools to which this book introduces the reader can be applied to performance that does not focus on text, such as dance, devised performance or experimental theatre. In fact, more concrete information about dance is given at various points in this book, as well as opera and film.

This book focuses on the various design methods, rather than one aspect of designing, such as drawing. While the basics of drawing and its role within design take up a lot of Chapter 2, there are plenty of alternative tools and methods available to the designer. This chapter, therefore, introduces the reader to the various other tools that the designer can apply when exploring and testing ideas. By doing so, this book intends to stress the explorative aspect to design and how vital it is in becoming a good designer. The understanding seems to be that designing costumes is the process of drawing a costume. However, a costume drawing is one of many tools to communicate a design and many designers choose to use other tools, such as draping, styling, collaging and writing, to communicate their ideas. How to do this effectively will be explored in Chapters 2 and 3.

No matter how good a designer is, understanding the performing arts’ industry and operating effectively within it are vital for a designer’s success. Chapters 5, 6 and 7 give an insight into the industry’s structure and how a designer functions within it, while Chapter 7 goes into more detail on how to break into the industry and become a successful designer. Chapter 5 outlines the different roles available to a costume professional and, specifically, to the early career costume designer. It also goes into more depth with the various career pathways available to the designer; it outlines options available to the designer to support their practice. Furthermore, Chapter 7 points out practices that the designer can follow in order to become an established designer and to stay relevant.

The book is structured to reflect the design process from beginning to end. At the end of most chapters, the reader will find a number of exercises to test the knowledge gained and to build up skills. However, when going through the book and the exercises in sequence, a speculative design process could be followed based on a script of choice. Used in this way, this book offers aspiring designers the chance to conduct a speculative design project on their own terms, potentially resulting in great portfolio pieces.

THE FUNCTION OF THE COSTUME AND ITS CONTEXT

In most contexts, the function of costumes is to help tell a story: of the characters, in particular, and of the narrative of the script, in general. In many cases, a costume is successful when it does not draw a lot of attention; however, other productions allow for more flamboyant costumes. This book will go into great detail with the reasons for deciding for one or the other, and who the professionals are who make these decisions; it will come as no surprise that it is not the designer alone. Chapter 3 lists a variety of factors, referred to as parameters, such as the genre, form, style, venue, text and the creative team, that determine the direction of the costume design, often without the costume designer having even gotten involved. The creative team, of which the costume designer is an essential part, develops a concept for a production and decides on its form and style. Form and style, as well as the genre, are often already determined by the text or the company producing and staging it. The costume designer needs to be aware of this and the costumes need to appear in unison with the production to which they belong. They need to follow its logic.

The Different Industries, Genres and Forms

Costume design is a versatile profession and allows for a varied career. It is common to find designers working across dance, musicals, opera and theatre. Some costume designers design for musicians and some designers collaborate with professionals from the performance art scene. However, while many designers would like to work across various industries, it can be a challenge to carve out a career working across all the live performing arts, as well as film and TV.

In order to make the point that a career across various genres, industries and scenes is possible, this book covers the costume design process generally and emphasizes the overwhelming amount of overlap. There are fundamental aspects to design that are independent from whether designing costumes for film, theatre, dance or music. This book introduces design methods and tools that can be applied across the various industries, genres and forms. Methods to conduct research, to find inspiration and to develop a concept follow a similar protocol across the wide range of design disciplines. Before specializing, an aspiring designer is well advised to gain a good understanding of the fundamental design elements, which is what this book can offer.

However, different forms, such as film, opera and dance, for example, require specific knowledge, which will be pointed out throughout this book. In order to do so, the book gives additional information on dance, film and opera in several dedicated sections. By doing so, it intends to empower the aspiring designer to cross boundaries and embrace the similarities, while knowing the differences.

Beyond the information given in this book, the reader who is interested in any specific knowledge regarding designing costumes for film, opera, ballet or period, for example, is well advised to keep reading more specific books on the desired subject. A list of relevant and industry-approved books can be found at the end of this book.

Alternative Contexts

Increasingly, there is a development toward a cross-disciplinary approach to the performing arts. The boundaries of the various disciplines are being challenged and moved. Some costume practitioners concern themselves with a more experimental and investigative approach to costume and apply their work outside the context of traditional performance. Not every project needs to start with a job offer or be dependent on a fee. There are many different career set-ups available to the costume designer. One of them could be working within an art context and creating costumes outside the boundaries of a traditional performance.

New opportunities for costume designers and artists are emerging. The rise of animation films, for example, offers numerous new pathways for costume designers and who knows what the future holds. The role of the costume designer and the work attached to it are not set in stone and can, and should, always be further explored.

WHAT TO KEEP IN MIND BEFORE ACCEPTING A JOB OR GETTING INVOLVED IN A PROJECT

Before accepting a job offer, it is important that the designer has obtained all the necessary information, in order to assess whether a project will be worth their time and effort. These considerations should be of a financial nature, as well as with regard to their portfolio and reputation. Money plays a role, but whether or not a designer accepts a job is not merely dependent on that. A job might not generate the designer a lot of profit but might give them more exposure. A job might give the designer the chance to try something they have never tried before. A job might be a welcomed challenge that the designer might want at this point in their career. A job might get the designer useful press coverage because of the venue, the nature of the project or the collaborators. There are many considerations and questions for the costume designer, which the following section outlines briefly.

Collaboration

Being a costume designer is a highly collaborative profession. For a lot of professionals, that is the appeal. It is important to be aware of the everyday reality of working with people and being dependent on them in many different ways. To know what to expect from a project is vital. Before starting a project with another professional, or indeed accepting a job offer, it is useful to find out some information about them. There are many different ways of developing and creating a performance and approaching the designing of costume. The designer needs to make sure that a project is suitable for them.

When meeting a director, for example, it is important to gauge expectations and the degree of creative freedom a production will allow for. A director might demonstrate a great interest in period productions, which might or might not be of interest to the designer. There should be scope for negotiation, but often enough there is not. That might not always be up to the director, it might simply be the nature of the project that restricts the creative decision-making. More information on that can be found in Chapter 3 (Parameters and How to Navigate Them). Some designers are happy to work to the director’s brief and a well-developed design idea; others, however, need a lot of creative freedom. It helps the director, the team and, actually, the designer themselves, to be clear about their preferences.

Nothing is worse than not voicing concerns in the beginning and then getting frustrated with a production and compromising it because of fundamental differences between the various creative people involved. Being clear and pushing for the best scenario while navigating hierarchies can be tricky and is certainly something a designer should, and will, learn over time. It is important for a designer to be aware of these different ways of working and to be realistic about whether a potential collaboration would be a fruitful match.

Challenges Concerning Experience, Diversity and Representation

Whether the designer feels that they are the right person for a production depends on their interests, style and work experience, as well as their confidence in themselves in being the right choice. What or who a designer represents and what their background is, could, and in some cases should, also play a role. The designer is advised to reflect on possible challenges before accepting a job offer or getting involved in a project. They might conclude that, for various reasons, they are the right choice. Equally, the designer or another member of the production team might not feel this way. Reasons for either of these views are multi-layered, and should be explored, discussed and reflected upon. It is good to keep in mind that concerns can always be challenged and, in many cases, should be challenged if the designer feels there are grounds to do so. Whatever the reason for the concern is, whether it has to do with experience, style, representation or diversity, any production benefits from a diverse and balanced team.

Money and Fees

While not every decision as to whether or not to get involved in a project should be dependent on money, a lot of the time it will be. Before accepting a job offer, the designer should find out the breakdown of fee, material and labour budget, and what will be expected of them. Ideally, there is a costume team calculated into the budget of a production and these individuals will have already been appointed, as would be the case when working for a large-scale opera or film. But often enough this is not the case and the costume designer will either have to find their team themselves or even take on other roles additionally to their role as designer. More detail on costume roles can be found in Chapter 5 (The Costume Team).

Workload

It is vital to find out exactly what the expectations for a role are, especially when they could extend beyond the costume design and into making, sourcing, repair and maintenance. The designer might not have the interest in, experience for or means to meet the requirements of a particular role. On productions with bigger budgets, the costume designer will have a costume supervisor and access to a team of specialized makers. On smaller productions, it is not uncommon to expect a costume designer to partly or fully make or buy the costumes or engage makers, especially in dance. The amount of work involved in a production becomes particularly important when the designer is already busy.

Initial Questions

Answering the following questions will help a designer with the decision as to whether or not a job is suitable. Furthermore, they will determine all of the subsequent design steps; most importantly, the research required for a costume design. They should, therefore, be the starting point for any costume design.

• What is the context? Is it a play, opera, a dance piece, musical, performance art, film, TV-series, music video or an advertisement?

• Who is the director? What is their style?

• Which venue does it take place in? What kind of venue is it? What is its location?

• Who are the people involved?

• Does the director, choreographer or producer already have some ideas?

• Is there a brief?

• Was the costume designer approached because of their particular style?

• Is there a script? Is it devised?

• Is it new writing, a classic or an adaptation?

• What time period is it set in and should be set in?

• How much freedom is there for the costume designer to make it their own?

• How many characters are there and/or how many people have to be costumed?

• What is the budget?

• What is the timeline?

1

TEXT AND RESEARCH

It is of great significance to the design process whether or not a production starts with a text, also referred to as a script or play-text. Furthermore, whether the creative team follows the text precisely, or merely uses it as a jumping off point, impacts the design process tremendously. Some theatre-makers might use a text as a starting point to explore themes in it and others might adapt a play, a classic, for example, to fit a new circumstance. Whichever option is being pursued, most theatre productions, films and TV shows, opera productions and musicals use text. Broadly speaking, this book, and particularly this chapter, will focus on text-based productions and how to approach the reading and analysing of scripts. The tools to analyse a script introduced in the following paragraphs are suggestions and not necessarily used by every designer. Many designers follow them in some sort of variation, time permitting, but certainly other designers will have different approaches.

Evelien Van Camp identifying themes and research subjects for The Importance of Being Earnest (1895, Oscar Wilde) created as part of the UAL Costume Design for Performance course, 2020. Organizing information visually can be helpful in understanding it, giving it more structure and remembering it.

Non-text-based performance, on the other hand, is an equally significant field of interest for many performance-makers generally and costume designers in particular. For some performance-makers, the focus might be the delivering of a particular message or the exploration of the body, a costume, an object, a building, a theatre or a site and its particular history. That does not mean that text will not play an important role later in the process, but it means that their work is not text-centred or does not use text as a starting point. A performance that is not text-centred might start with a research and development phase, as opposed to analysing a script, and continues with the exploration of ideas or materials, which will be introduced in detail in Chapter 2. The designer might respond to situations arising during rehearsals, which is particularly common in devised and experimental theatre, as well as contemporary dance.

READING AND ANALYSING A SCRIPT

The aim of conducting research is not only finding more information, it is about being immersed in the world of the play. Sometimes that extends to the world of the playwright and the time and location the play is set in. Before reading a script, it might be advisable to find out whether there are any publications or playwright’s introductory comments available. Furthermore, it will be useful to find out when the play was written and whether the script specifies a date or period in which it is set and where it is set. Some designers will also try and find out what the playwright’s influences or their interests and motivations were. In the case of a newly written script, there might be the possibility to speak to the playwright directly. In most cases, when getting involved in a production of a new script, the playwright will be an essential part of the team with a great influence on the production. Before reading the script, it might be helpful to do brief research on it, the playwright and the time and place the script is set in. This will help to easier understand the script when reading through it. In the case of The Importance of Being Earnest, for example, a play written by Oscar Wilde in 1895, it will be inevitable to learn more about Oscar Wilde, his life and the time he was living in when trying to gain an understanding of the script. It seems significant to know that he was married to a woman, yet had a male lover. His double-life shows obvious parallels to the protagonist in the play. The knowledge about Wilde having had to deny his homosexuality, as it was strictly unlawful to engage in a romantic relationship with a person of the same sex, opens up the text to a deeper understanding.

Looking at social, political and artistic developments of the time a script is set in, will further its understanding. Oscar Wilde participated in the trend of being a dandy and was a part of the aesthetic movement. This knowledge not only helps with the interpretation of the text, but also with finding inspiration and a design approach. A Streetcar Named Desire, a play written by Tennessee Williams in 1951, centres around a woman with a particularly fragile mental state, who visibly deteriorates over the course of the play. It might be useful to know that Williams’ own sister was diagnosed with schizophrenia a few years before he finished this script. Whether or not that gives any more insight into the play and, furthermore, can inform the costume, cannot always be measured in a direct way, but it gives the designer a deeper understanding of the context of the script. What is important for the designer is to have a full understanding of the text, its context and its world.

The First Read-Through

The first read-through will become more useful, and possibly even more enjoyable, when the designer has researched the main facts about the script beforehand. However, some designers might want to just read it and let the message and its ‘feel’ naturally emerge, rather than diving right into an analysis. Other designers might start analysing the script immediately and want to find as much information about it as possible. While this might be a matter of preference, other factors like time might require a designer to start analysing it straight away. It is common for a designer to read a script to determine if they want to get involved in the production. In this scenario, they would not invest any more work into it other than a quick read through. In the case of a classic text, for example, it is likely that the designer is already familiar with the material and starts their process by working through the text already in more detail. Either way, the designer will have to read through the text several times at several stages over the course of the production period. When working on a theatre production, the designer will likely be invited to a ‘read-through’ at the beginning of rehearsals. While this gives the designer the chance to hear the words and see the actors, it is often too late in the process to have an influence on the design. The designer should try to imagine the scenes and how they could appear on stage. This will help them to gain a better understanding of the story and the potential of the design.

Research and costume design ideas by Jody Broom for Blanche of A Streetcar Named Desire (1951, Tennessee Williams), created as part of the UAL Costume Design for Performance course, 2020.

Initial Questions When Reading Through a Script

CHARACTERS

• How many characters are there?

• Who are they and how do they relate to each other?

• Where do the characters come from and where are they going?

• Are there any costume changes?

• What does the play indicate that the characters might wear? Is anything specifically mentioned?

• Who is in each scene and where do they enter and exit from?

• Can some characters form groups?

• Is there an ensemble? Do they sing/dance? How many of them are there?

There will often be a character list at the beginning of the script, stating the character names and, in some cases, the age, relationship to other characters and their social position.

LOCATION

• What are the different locations?

This includes countries and regions, cities, landscapes, whether it plays indoors or outdoors, possibly the type of house, rooms or something more abstract or undefined, e.g. ‘a frightening place’.

TIME

• What is the year, month, day, season and time of the day in which the play and its various scenes are set?

• Is there a significant jump in time somewhere in the play?

• Is the play going back in time or jumping backwards and forwards?

• Is there a change in period?

Making sense of time is crucial to understanding the journey a character takes and the costumes they will wear throughout.

UNDERSTANDING DRAMATIC STRUCTURE ACTS/SCENES AND UNITS

• How many scenes and acts does the script have, what happens in them and who appears in them?

A play, opera or musical is made up of a number of scenes. These scenes are grouped into acts, which structure the narrative development. Scenes contain a group of characters in a particular location in a moment in time. A scene change is when the location or players on stage shift. Sometimes, the playwright does not use scenes and acts to structure the script. In this case, the designer and director need to break the script down into scenes themselves in order to ease the design process. Furthermore, the designer might want to further break down the scenes, into so-called units, to indicate a change in direction of a scene, such as its energy, mood, purpose or tone, for example.

STAGE DIRECTIONS

• Are there stage directions and, if so, do they need to be followed?

Stage directions are comments made by the playwright about the characters, setting or atmosphere, for example, but their purpose can vary widely. They can give the reader more information on what has happened or is happening in a particular scene, for example. They are not part of the script. They can help the reader to understand the playwright’s intent or they can be about the staging or technical aspects. They are a useful reference, but they do not need to be followed entirely, unless otherwise stated in the designer’s contract, by the playwright or, indeed, if the director insists and there is no ground for negotiation.

MOOD AND ATMOSPHERE

• What is the mood and atmosphere of the play or individual scenes?

They are often commented on in dialogue or described in the stage directions, for example, comments about the weather or quality of light.

A FEW MORE QUESTIONS

• What season is it and does this change?

• What time is it and how much time passes from the beginning to the end of the play?

• Is there any symbolism in the play?

• What are the overall themes?

• What is the message?

• What is the essence of the play?

These are complex questions, and they will not all be answered after the first read-through. It might take a few readings and conversations; for example, with the director or even the writer, if that is an option. However, it is important not to lose sight of these questions and to keep trying to answer them. A significant part of designing is being organized and disciplined. Logical thinking and thinking ideas through are essential.

Tools to Analyse a Script

Whatever the approach to analysing a script might be, applying a method will significantly help structuring the answers to the above questions and any thoughts resulting from them. While every designer develops their own unique design approach, there are a number of tools used by designers in some sort of variation, even if they are not fully aware of it. The following sections introduce the reader to the most common ones.

THE SCENE BREAKDOWN

Conducting a scene breakdown is the most time-consuming of all the tools, but it is also the most useful first step in the design process for a play or film. The designer will go through the script and note down all necessary information, as well as their own thoughts, in relation to their findings. Many scripts are already divided into acts and scenes, which is a good starting point for the designer to structure their script breakdown. For various reasons, the designer can further break down the script into units. That would be an individual choice and concerns mostly design considerations, such as costume changes, character appearances, props requirements, set configuration, video projections and changes in lighting, music, mood and atmosphere. The best approach to organize this information is to insert it into a chart, rather than just using a list. The information collated in this chart can be actual facts from the script, their interpretations by the designer, as well as their notes and thoughts. The aim of the chart is not necessarily to get all the facts right, it is first and foremost to understand the play and how it unfolds scene by scene. This is not a document that needs to be shared with the director, although it will greatly help conversations with the creative team.

This chart is an example of a scene breakdown using the opera The Barber of Seville (1816, Rossini). It is not meant to be exhaustive but to give an idea of how a scene breakdown could be approached.

MAPPING THE APPEARANCE OF CHARACTERS THROUGHOUT A PLAY

It can be very helpful to know how many performers there are on stage at one particular time in the play and the general flow of people coming on and leaving the stage throughout the play. The work of the designer becomes particularly interesting and relevant when characters appear together on stage and consequently form an image. The more characters there are on stage, the more visible the design concept will become. This is the moment when characters are seen in relation to each other, and colours and shapes often grow in importance. This is where costume design gets more complex, but it is also the moment when the costume designer can shine. The best way to make sense of the characters’ movements is to make it visual, in a chart, for example, and by colour-coding each character.

Mapping out the movement of characters can be very helpful for understanding the flow of the play or to determine whether costume changes will work. This chart is an example using Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (1895). To allow for a clearer picture, the script was divided into scenes as well as acts, although Wilde used only acts to structure his play. To see the flow of characters coming on and off the stage, it can be helpful to use a different colour for each character.

CHARACTER’S QUOTATIONS CHART

A helpful way to find out more about the characters is to gather what characters say about each other in the script and note it down. An effective visual solution to this might be to draw up a chart that lists all characters in the first column and again across the first line. The first column indicates the quoted characters, and the first line indicates the characters whom they talk about. It becomes clearer when looking at the example.

Example of a character’s quotations’ chart using the play Enron (2009, Lucy Prebble). Characters talk about each other and while this is not always truthful, it still reveals something about both characters, the one who said it and the one who was talked about. References to clothing are of particular interest but other information that helps to develop a character should also be paid attention to.

UNDERSTANDING THEMES AND MOTIFS THROUGH VOCABULARY