18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

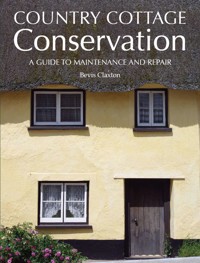

Country Cottage Conservation is essential reading for everyone who loves rural cottages. From simple DIY redecoration to employing architects and builders to tackle significant repairs, this book is full of helpful information. The author explains how cottage owners are able to protect and enhance their investment, and discusses various repair and redecoration options and their consequences. The charm and long life of a traditional cottage comes from over a thousand years of building tradition that was almost forgotten in the twentieth century. Modern materials and techniques are often expensively inappropriate, as they can conflict with the buildings' inbuilt defence mechanisms or make cottages look too modern, yet it is still possible to repair a cottage economically with traditional methods and natural materials that work in harmony with the original construction. The author also considers what may be done to redress the balance where inappropriate work has previously been carried out, so as to restore some of the original performance to the cottage and help preserve its charm, and value, for the future. Essential reading for everyone who loves country cotttages and invaluable for those who want to maintain and repair their property in a sympathetic and sustainable way, it is also superbly illustrated with 239 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

COUNTRY COTTAGE

Conservation

A GUIDE TO MAINTENANCE AND REPAIR

Bevis Claxton

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2010 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Bevis Claxton 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 967 4

The right of Bevis Claxton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Disclaimer

The author and the publisher do not accept liability of any kind for the use of material contained in this book or any reliance placed upon it, nor any responsibility for any error or omission. The author and publisher have no control over how the information contained in this book may be used and can accept no liability for any loss, damage, injury or adverse outcome however caused. Third parties and websites are referred to in good faith but with no responsibility for their advice, behaviour or the content of their publications. Laws and regulations are subject to variations across the United Kingdom and to changes with time. Conservation experience, living conditions and the adjustments necessary to cope with climate change may develop and alter over time. The information contained in this book is necessarily generic and cannot relate to each individual building or circumstance and should not be seen as a substitute for specific professional and technical advice.

Drawings and photographs all copyright Bevis Claxton/Old House Info Ltd

Frontispiece: A country cottage shows how to build to last using sustainable local materials; it also records human capabilities, and recalls human experience, from before the machine age.

Contents

Dedication and Acknowledgements

Introduction

SECTION ONE: OLD AND WISE A cottage is not a modern house

Chapter 1

Thinking of Living the Dream?Some perspectives on the idyll

Chapter 2

The ProfessionalsThe right help when needed

Chapter 3

Don’t Bring Me DownTraditional management of movement in cottages

Chapter 4

The Air That I BreatheTraditional management of damp in cottages

SECTION TWO: THE WAY WE WERE Cottages as they were built

Chapter 5

A Hard RainTraditional roofing

Chapter 6

Sticks and StonesTraditional walls, partitions, chimneys, floors, ceilings and stairs

Chapter 7

Knock on WoodDoors and windows

SECTION THREE: THE PRESENT And what the twentieth century did

Chapter 8

This Old HouseRoutine maintenance for cottages

Chapter 9

Reasons to be CarefulAwareness of some common domestic dangers

Chapter 10

Heat, Light and WaterMarrying modern building services with ancient construction

Chapter 11

Get It Right Next TimeAddressing inappropriate past work

Chapter 12

Paint It … BackStripping inappropriate or harmful paint

Chapter 13

Fungus and Other BogeymenPutting rot into perspective

SECTION FOUR: IN THE YEAR 2525 Preparing for the future

Chapter 14

Future PastUnderstanding sustainability

Chapter 15

Hot LoveHome insulation pros and con

SECTION FIVE: STYLE COUNSEL Keeping the look alive

Chapter 16

Bits and PiecesInteriors and accessories

Chapter 17

Come OutsideSite and garden, animals and trees, porches and outbuildings

Postscript

Further Information

Index

Dedication

To my parents who, as children, experienced real rural life in several country cottages – and have stayed well clear of them ever since.

Acknowledgements

The photographs in this book include a few of the author’s own projects, but mainly the images are as noticed around the country and assembled to illustrate the contents in a wider context. Information has been gathered in a similar way, much directly experienced and much learnt from sources too widespread and too numerous to acknowledge individually. Thanks are due to all those who have contributed in some way whether by passing on information and experience at some point in the past, or by keeping their cottages looking fine enough now to photograph. Two of the author’s drawings first appeared in different form in Old House Care and Repair by Janet Collings (Donhead, 2002), and a couple more in Maintaining and Repairing Old Houses: A Guide to Conservation, Sustainability and Economy by Bevis Claxton (Crowood, 2008). Some of the information presented here has also appeared in different forms in articles and on the website www.oldhouse.info.

Introduction

WHAT THIS BOOK IS ABOUT

The information

This book sets out practical information that can help owners to keep their cottages viable and attractive. It aims to help bridge the information gap – between recognizing the need for action and deciding on what action to take – by providing some understanding of the special nature of cottages and how repairs and redecorations may affect them for good or ill. This information can be of help to owners whether they propose to carry out work themselves or engage others to do it for them. Cottages were designed cleverly to keep themselves intact despite dampness and movement. This technical performance is due to the way in which they were designed to use natural, sustainable materials, and it was also linked to the way in which people lived in their cottages. The visual appeal of cottages follows naturally from the authentic materials and their technical design. This book explains how some of this original look and function might be restored and preserved for the future.

Identifying the problems faced now

This book also looks at the condition in which most cottages have arrived in the twenty-first century. In addition to the problems of time and wear, cottages have not been served particularly well by many of the industrialized products and building methods of the twentieth century that have been, mainly innocently, applied to them. Most country cottages have been through several rounds of refurbishment since rural workers began to leave them a century ago. Books published since the 1950s have often tended to address bringing cottages up to contemporary standards of comfort, ‘doing them up’, frequently involving extreme rebuilding in the twentieth-century manner.

But the problems faced by a new owner today are much more likely to be about whether those twentieth-century repairs are mismatched with the original construction, and failing in some way, and whether recent refurbishments have also robbed the cottage of the character that once made it so attractive. What can be left of a cottage in many cases is not so much cottage, more a poor imitation of a modern house.

HOW THIS BOOK IS ORGANIZED

The chapters are organized within five sections, each identified by coloured pages:

The first section, ‘OLD AND WISE – A cottage is not a modern house’, introduces some essential information about taking on a cottage today and where help can be found in assessing a property for purchase or repair. It also explains in a straightforward way the big differences between a cottage and a modern house in terms of how damp and movement is managed. The persistent and continuing misunderstanding of these important qualities by owners, builders and professionals has arguably been responsible for the advancement of decay in countless cottages during much of the last century – so it’s worth knowing before considering new work on any cottage.

The second section, ‘THE WAY WE WERE – Cottages as they were built’, examines some of the more common constructions used in cottage building, including some principal variations of materials used for roofs, walls, doors and windows as found in different regions of Britain. This section also looks at how those traditional constructions emerged from the necessity to make use of what the countryside was able to provide, and the limitations imposed by lack of transport and machinery at the time. These intrinsically sustainable methods and materials should, nowadays, also be of use, informing modern environmentally conscious design in new housing.

The fourth section, ‘IN THE YEAR 2525 – Preparing for the future’, imagines the cottage in the future. Cottages can offer practical lessons to the twenty-first century on how to build durable, sustainable and beautiful low-impact dwellings from what was once immediately available, all without using up fossil fuels or industrial quantities of energy. Cottages were highly sustainable when their occupants had no choice but to live sustainably themselves. But now we have become used to living unsustainably, and because most people in Britain are likely to continue to feel that they deserve more than nineteenth-century levels of comfort, this section looks at how we can try to match our own unsustainable needs with a cottage’s sustainable heritage – including insulating cottages appropriately.

Section three is ‘THE PRESENT – And what the twentieth century did’. For the best part of a hundred years now, most cottages have not been used or repaired in the ways that were originally intended. In many cases cottages were cast off as slums and then perhaps taken on by wealthier people to use as holiday homes; some have survived as permanent homes, most have been ‘modernized’. Like many a collectable antique item or classic vehicle, they have passed through a period of being underestimated before they emerged as desirable survivors. This section looks at appropriate maintenance and repairs, and also what might be done to redress past works that may have been inappropriate.

Finally section five, ‘STYLE COUNSEL – Keeping the look alive’, offers some ideas on presentation, inside and out. This is not intended to impose any particular ‘period lifestyle’ but rather to highlight how easy it is to over-dress a cottage and to lose the simplicity that is, after all, the essence of a cottage’s attraction. This section also examines a few of the practical problems often faced, including getting a fireplace to work properly, extending a cottage sensitively, and incorporating kitchens and bathrooms.

ABOUT TO BUY A COTTAGE?

Cottages are often less convenient to live in and more expensive to buy than the equivalent modern house, so there is something that puts them into a similar category to antiques and classic cars. The owners of those items happily accept some limitations in performance in return for the interest they give and the attention they attract. Those owners also tend to take great care to use only authentic materials in their repair. The same is reasonable for a cottage – but the message that one day a cottage could be worth less if it has been poorly ‘modernized’ has to fight to be heard above the clamour of sales pitches for home improvement products. Owning a cottage can present an opportunity to engage with a different sector of the economy, one that is involved with natural materials and ancient crafts.

THEN, WHAT IS A COTTAGE?

This book assumes that a country cottage was built for rural workers any time up to the modern period, when modern industrialized building materials took over. This ‘modern period’ was a result of the nineteenth-century’s industrial revolution, but there were still country cottages being put up with basically mediaeval technology for some time after, perhaps as late as the 1930s. Estate agents sometimes like to extend the term ‘cottage’ to urban terraces and ‘artisans’ dwellings’, and indeed some of those built in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth will owe much more to the traditional construction that this book is concerned with, than to the newer conventional ‘modern house’ methods.

It took some time for industrialized materials to displace old habits. Those late Victorian, Edwardian and later urban ‘cottages’ are, however, likely to exhibit ‘hybrid’ constructions – blends of ancient and modern. In a similar way many ‘genuine’ country cottages will have become hybrids in that they have been extensively altered in the modern period. But even in those cases an understanding of traditional building ideas is still very useful in making decisions on future repairs.

Country cottages may be grouped in a hamlet…

… or equally in a village or country town and then, when do they become houses?

Perhaps the typical country cottage stands alone in the countryside. Its accommodation may often have been tied to a particular job of work …

… or cottages may have served other needs such as almshouses; sometimes a larger house was subdivided into cottages, or the other way round, and back again.

The nineteenth century produced the ‘cottage orné’, an elaborate and probably quite expensively embellished version motivated either by a desire to improve the lot of tenants or to make a country estate look more jolly. By the end of the cottage era, cottages were more often designed by draughtsmen than by the ‘builder’s eye’, and their technology and function were often assimilated into the council house.

RESPECT FOR THE PAST

Gone …

Too much has been done to most cottages to ‘turn back the clock’ and recreate an authentic restoration of their past, either in technical function or in visual appearance. A full restoration would anyway be more appropriate to a museum because it would have to reflect the life of people living perhaps six to a bedroom with one main wood fire that had to be tended all day, every day. Some of those folk lived in the shadow of perpetual fear of eviction, disease, starvation and infant mortality – the echoes of that way of life are still remembered by some. Needless to say there were no bathrooms, no indoor WCs, no electricity, no central heating and often no piped water. Cottagers were poor, way beyond the scope of modern British definitions, and cottage life itself was nearly drawing to an end before most were allowed any political voice or offered any significant state safety net.

… But not forgotten

We may have a romantic vision of cheery ploughmen and rosy-cheeked milkmaids, some of whom may actually have been lucky enough to have enjoyed an uncomplicated life under the paternalistic care of others. But cottage dwellers were, in practice, slaves to their condition, and their labour in the countryside provided essential services, such as putting food on the tables of the nation. The simple, frugal and obedient way of life they were required to adopt has inspired some onlookers to label their condition as noble and romantic; others considered them exploited.

A rare sight now, cottages no longer inhabited but still in their original form. It was the availability of many so-called ‘slum’ dwellings in similar circumstances that fuelled the country cottage boom of the mid-twentieth century, helped by government grants. Conservation knowledge was rarely applied then, and many such cottages went on to become, literally, modernized.

Nowadays untouched cottages are considerably rarer, and the more likely situation is a cottage that was modernized years ago but which would now, once again, be considered in need of attention. This book hopes to help bring cottages together with a more sympathetic kind of attention this time round.

So if we do examine ways in which to ‘restore the past’, then perhaps it should be with respect for the memory of past occupants, their fragile lives and their building skills. In looking after cottages we can do this by preserving the old materials and artefacts that survive, and resisting the temptation to apply a sugary varnish to the events they record. The smallest evidence of the real past can be beautiful, human and touching enough.

THE FUTURE

Gone …

There is a common thread between the emptying of rural labour from cottages and the refilling of those same cottages by commuters or holidaymakers, and that common thread is mechanized transport. As the steam traction engines and diesel tractors came to the countryside, so the manual labour and horse-power began to be shown out.

Then steam trains, petrol-powered cars and buses allowed people to work in the towns and live or play in the countryside. Ironically some of the new ‘townie’ incomers will have been descended from the agricultural workers who previously had to leave the countryside, and this perhaps accounts for the nostalgia that surrounds cottages.

… But coming back?

But it is becoming possible that, in the near future, fossil-fuel depletion could turn back the clock. Even if we do not see a reduction in the use of powered vehicles, we are increasingly likely to have to create our new homes almost entirely sustainably, as our forbears did, and that means with much less reliance on imported and highly processed materials.

This book examines some of the lessons from inherently sustainable traditional building materials and techniques that were used for centuries before our dependence upon fossil fuels. These ancient ideas are already being dusted off in preparation for being re-adopted for sustainable building in the future, and these old traditions of sustainable building have even more to offer than most people perhaps yet suspect. The future may not consist of the exciting silver things on stilts that we were promised in the 1960s but, instead, revived versions of the cottages that the 1960s saw being demolished.

Using proven and reliable resources

The sustainable and naturally abundant materials that have been used to build cottages were understood for a thousand years, the traditions handed down through practical apprenticeship. The modern age almost wiped out that knowledge. Many are now pioneering an alternative sustainable construction using ‘waste’ materials such as used tyres and straw bales, which is admirable. But those materials are arguably only available as by-products of an industrialized system of living, farming and transport that may well have to change soon. The traditional materials used in cottages were well understood, better than our conventional modern materials, and better also than the new ‘recycled’ materials. There was simply more time to get to know them over a millennium. There is no need to wonder how well traditional construction may perform over time – every surviving cottage is evidence of what can be achieved using what the natural world delivered, without waste. All we have to do to ensure a continued supply of natural materials is to look after the natural world.

Preserving interest: preserving value

Apart from what cottages can teach us to help cope with the future, they are also records of the past. This may be a novel idea to those who are more used to new houses and who have wanted to make them their own and alter them to take account of new fashions. But the reason that a cottage may well cost more than a new house is that it is, in effect, an antique – and a unique one at that. Alter or modernize an antique and its value generally diminishes.

Old country cottages may now have found a new type of owner, but will there be a new generation of cottages built in the countryside for farming use again, using some of the same sustainable materials?

A small example of the frailty of the past: the burn mark made by a candle or taper where it was routinely attached to a post hundreds of years ago; a coat of varnish would obscure it, or a coat of paint, and it might be lost forever.

The corrugated iron porch may be practical rather than elegant but it is a reflection of the reality of cottage life until recently; the smartened version of the porch next door has not been over-elaborated, and seems commendably restrained.

So this book addresses the ideas of repairing and retaining original fabric rather than just renewing something when it needs attention. A related idea is that of ‘reversibility’, which here means that, in order not to devalue the antique nature of the cottage, any necessary changes should be made, if at all possible, so that they can be completely undone in the future without leaving a permanent scar on the cottage.

SECTION ONE

OLD AND WISE

A cottage is not a modern house

Cottages were the simplest of dwellings, which might originally have been built straight on to trampled earth and using scraps of wood, mud, straw, twigs, blood, hair and dung. Despite the primitive farmyard flavour of that list, all the ingredients would have been assembled and used to best advantage in accordance with a thousand years of word-of-mouth research and development. Although it lacked our modern calculations, certificates and official approvals, a cottage had to be every bit as technically integrated a product as the most modern building is today. But much of that building skill and understanding was wiped out by the social upheaval and technological change following an industrial revolution and two world wars.

When the twentieth century devised new building materials, the well tried ways of building with what nature provided began to be forgotten. Newer substitutes sometimes offered apparently enhanced performance, sometimes needing less time or less skill to use. This new building technology obviously works well on its own and has provided clean and efficient homes for around a century. But modern building technology functions in some very different ways to traditional sustainable rural building technology, and mixing the two technologies in the same building can cause one or both to fail. Acceptance of this came, through bitter experience, late last century – yet some find that experience hard to accept, and will still try to force the two technologies together.

The simple materials that our ancestors spent so long refining and understanding were also, in our modern terms, highly sustainable and largely natural materials. In a world that pre-dated the internal combustion engine and electricity, low energy living was a necessity and not a lifestyle choice. They had to be good at it to survive. Recycling (and avoidance of waste in the first place) was also necessarily second nature. Their buildings have been proved capable of very long life – much longer than modern homes dare to claim. Cottages were once designed to be heated, not by imported fossil fuels but by what nature provided locally – wood; and wood we now recognize as a ‘carbon-neutral’ fuel in our world that is threatened by climate change.

So a cottage has real answers to our present building crisis: highly sustainable, long life, natural materials, minimal transport, renewable energy and carbon-neutral heating. Yet despite these clear virtues, old housing has long been under threat of being swept away to be replaced by something flimsier made from components that come from factories hundreds of miles away. Cottages can teach us so much about how we might adapt to live responsibly with our planet in the future. If only we would stop trying to force them to conform to last century’s outdated and unsustainable ways. But that is for Section Four, first …

The chapters in this first section introduce some differences between cottages and modern homes that can affect the way they are lived in and looked after, and which it would be useful for any prospective cottage owner to understand before crossing the threshold:

Chapter 1: Thinking of Living the Dream? – Some perspectives on the idyll

Chapter 2: The Professionals – The right help when needed

Chapter 3: Don’t Bring Me Down – Traditional management of movement in cottages

Chapter 4: The Air that I Breathe – Traditional management of damp in cottages

CHAPTER ONE

Thinking of Living the Dream?

Some perspectives on the idyll

THE EMOTIONAL SIDE

Many of us are attracted to a country cottage in much the same way that people are attracted to chocolate: it is an in-built yearning that was implanted in us very early in our lives. So it is probably no accident that chocolate boxes have had a long history of being adorned with pictures of cottages. But chocolate is a craving that is quite cheap to satisfy, while cottages are more expensive.

If already gripped by a desire to live in a cottage it can be difficult to step back and analyse what makes the idea attractive, but as there is a lot of money and happiness at stake, it’s worth making the effort. The appeal of a cottage is often visual, so we can try an experiment with that side of things first. Take a good look at a real cottage: for this to be as scientific as possible, find a cottage that is close to its original appearance. (A village or holiday cottage owned and maintained by one of the National Trust charities, one of the national conservation organizations, or perhaps a large country estate might be good places to look – the majority of cottages found in country lanes and in print are, like many of the examples photographed in this book, already well in the grip of the twentieth century.)

Now take a good look at the cottage pictured. No two examples in the country will be the same because the British Isles have a rich variety of landscapes and geology, from which cottage building materials came. But despite regional differences there is every chance that a good example from anywhere in the country will display many of these characteristics:

The walls and roof may appear irregular, or downright ‘wonky’.

The doors and windows may be familiar-looking, but not standard designs.

There may be evidence of charmingly crude, but effective, hand-made repairs.

Surfaces, even when soundly decorated, may appear uneven or blemished.

There may be features left over from the past that make no current sense.

Much of the character of a cottage is linked to evidence of its original purpose and condition, so the less this is overlaid with suburban neatness, the more of a cottage it will appear.

Cross-dressing: the use of modern materials for repair and decoration can now give cottages an industrial age veneer. At the same time, new houses are deliberately being built to try to look pre-industrial.

The reflections from the window in the red wall (above) show the contrast between older, slightly ‘crinkly’ glass, bottom left pane, and more perfect later glass. The straw-coloured wall (below) shows that an informal ‘imperfect’ quality also gives character to walls. Much cottage character is due to subtle visual imperfections and irregularities; iron those out and some charm evaporates.

Now picture an image of this cottage on a computer screen about to be manipulated by some software – by which the outlines are first straightened, the doors and windows are replaced with modern standard patterns, the old repairs are swept away, the surfaces are made much more uniform in colour and texture, and all the old superfluous features are done away with. The result the computer screen shows might be cleaner looking and more rational, but would it still look like a cottage?

The real life version of the imaginary computer exercise described above is almost precisely what so many cottage owners have actually done to their homes, and at great financial cost. Not at all because they are mad or vandals, and no one would doubt that they love their homes, but because they have been drawn into the modern-home way of looking at things that promotes straight, clean, tidy and new. Nothing wrong with those things in the right places, they just don’t seem very ‘cottage’. Maybe they did not know that there are other ways of going about repairs and redecorations that can preserve character. Or maybe they would have been happier with a new house instead. A lot of people are put off real cottages by some of the ‘down sides’ sometimes associated with them:

No off-street parking, or difficult access.

Curious boundary arrangements, including ‘flying freeholds’ and remote gardens.

Poor acoustic insulation between attached properties.

Necessity to negotiate some routine repairs and redecorations with neighbours who are under the same roof.

Inability to totally exclude unwelcome wildlife, such as rats, mice, birds, insects and spiders, from old walls, floors and roofs.

Poor thermal insulation that does not sit happily with current heating methods, and which might be awkward to improve without destroying the character or fabric of the cottage – and therefore necessitates lower indoor temperatures.

These ‘deficiencies’ are not so much due to age or deterioration, but more to do with the modern expectations we have learnt from modern houses and the modern levels of comfort that we demand. In other words they are not so much a result of a cottage being old and worn out, it is because we are new, we have become more fastidious, and we are trying to make cottages do different tricks to the ones they are good at.

But there is one last possible drawback with cottages that demonstrates how hearts can rule heads:

A cottage has frequently tended to cost more than a modern house offering similar accommodation.

This should, even for the non-romantic, be a persuasive argument for keeping their investment looking more like a cottage and less like a modern house.

Just old-fashioned

There is a lot of debate about whether new buildings should be styled according to traditional values or be entirely free from past constraints. Fair enough when it comes to the style of a new large public building, but when people have decided that they want an old country cottage there seems little question that what is wanted is the past, and in spadefuls.

Horse sense

If the modern owners of an old cottage also had a horse, they wouldn’t dream of feeding it diesel instead of hay; nevertheless, many will happily force feed their cottage on modern building and decoration materials that are potentially just as ridiculously inappropriate. A mis-fuelled horse may fall over and die quite quickly, but a mis-decorated house can continue to stand and even look reasonably sound – yet within its walls, softening and decay could be taking hold.

THE TECHNICAL SIDE

The cottages that people might now dream of living in would have been built in the days when horses were still everyday transport: a very different age. Nowadays, a small modern house might even try to look a little like an old cottage, if a little smoother and straighter. It might have similar-looking bricks, timber, paint and render. But if this modern small house is built in the conventional modern way, there the similarity ends – because modern houses, and many of their materials (including the bricks, timber, paint and render), can perform entirely differently to olden traditional construction in several very important ways. And so a cottage needs to be looked after in a different way to a modern house – simple enough.

The problem is that people have been seduced into applying modern maintenance methods to their cottages, and unwittingly they have created problems involving dampness and decay. So they have had to go on and spend more money rectifying those problems. The time has now come when a lot more is understood about how old buildings worked, and how cleverly they coped with ageing. Cottages can’t be bludgeoned into being new buildings, and it can often be better for them, their owners and their bank balances, if they all decide to work in the same way – the way the original builders intended. Those men and women had, after all, been building on a thousand years of ‘trial and error’ experience in their locality. Our modern building regulations have been around for only a twentieth of that time, during which they have had to be revised as problems have come to light – and more will no doubt have to be readdressed. Cottages were built on a more mature set of ‘rules’ that are worth trying to understand.

So it is not simply judgements about visual quality that make conservation architects, planners and historians unhappy when they see some modern materials and modern building practices applied to old buildings: there may be sound practical reasons why some of these innovations could be unsatisfactory or why they might cause serious problems in the future. The modern cottage dweller needs to be aware of them.

Cottages breathe, or at least they should

House building in the pre-industrial world (the changeover happened some time between the late nineteenth century up until several decades into the twentieth) had to rely on what is called ‘breathable’ construction rather than the modern practice of near-total water-tightness. This was simply because there were very, very, few traditional building materials that were reliably totally watertight in long-term use. So buildings were assembled to shed what rainwater they could, while other sources of damp, such as ground dampness and internal condensation, were dealt with by the constant and unavoidable ventilation that fed open fires and ranges. Walls and floors would have been in a constant cycle of wetting and drying, and they relied on the drying power of the sun and wind externally, and a permanent fire and its draughts internally.

Like an old-fashioned woollen overcoat, an old cottage might have kept its contents dry in a shower by a combination of deflecting most, and soaking up some, rainwater, but all the time letting out the wearer’s perspiration. With luck it stopped raining before the cottage walls, or our overcoat, were saturated and began actually to admit water. Once the rain did stop, then like the coat, the walls would dry out in the sun and wind, and in that way mould and rot were less able to take hold.

But cottage owners need to understand that applying a coat of modern waterproof paint or render to an old cottage will have similar results to trading in the woollen overcoat for a bin liner: pretty good for the first fifteen minutes, pretty dire after an hour or two when the inside is running with sweat. In terms of a cottage this sweat translates into condensation and dampness that becomes trapped inside the building materials, and that can cause decay.

The modern-built house can take advantage of modern waterproof construction and finishes that should have been assembled within an integrated design, soundly joined together to banish all damp and wet. The insides of things, we hope, never get wet in modern construction. But in a cottage they do, and it is too late and too costly to rebuild them so that they don’t (and if we did they would no longer be cottages). The cottage with just a few modern finishes applied here and there would still be taking in water in some places, yet unable to get it to dry out completely through the waterproof bits. Imagine what condition parts of your body would be in if wrapped permanently in plastic. Exactly. (See alsoChapter 4: The Air that I Breathe.)

Cottages may flex, like they always have

Cottages were by definition not top-of-the-range housing. In the rockier areas of the country they might have been lucky enough to have had really firm walls of stone founded on good solid rock. But cottages were often built in rock-free areas out of less firm materials such as sticks and mud, and they were put straight on to the soil, or as near to it as made little difference. Mobile subsoils, such as clay, could affect the walls then, and still will now, so seasonal movement has always been likely. A cottage of timber construction is particularly prone to seasonal movement, as the timber itself responds to atmospheric and seasonal humidity, regardless of any soil movement.

Regular minor movement translates into minor cracks and niggly defects such as binding doors and windows, or draughts. But without destroying everything that is there and rebuilding the cottage from the ground up as a new house instead, and with modern materials, this slight to-and-fro movement is unlikely ever to be arrested. Not recommended! To the original cottagers the movement was of little consequence because, happily, old-fashioned building and decorating materials and styles happened to be quite tolerant of movement (modern ones can be less forgiving). There is no reason why we should not go with the flow and use those same movement-tolerant materials today. They are usually very simple, and can even be cheap, it just needs some patience to find someone who knows their mud, clay, lime, or whatever.

Modern building and decorating materials, on the other hand, have been designed with modern houses in mind. Modern houses are designed with deep, rigid foundations so as not to flex and settle, and applying to them the modern renders and coatings formulated for a stable background such as a new house is as simple and effective as icing a good solid fruit cake; any fragile coatings are unlikely to be tested by movement. But applying some of the more brittle modern materials and coatings to an old cottage that is bound to move is just not going to be as successful. Instead of being like icing a good solid fruit cake, it is probably going to be more like icing a sleeping dog: promising at first perhaps. (Don’t try this at home, see alsoChapter 3: Don’t Bring Me Down – ‘Why new houses don’t like to move, but old cottages don’t mind’, page 38).

Even the draughts caused by movement (perhaps as it had affected the fit of doors and windows) were useful to a degree in a traditionally run cottage: there was most likely a permanent fire in the hearth, which provided heat, light and served all cooking, and this fire actively needed draughts to feed it with oxygen to burn. What was also useful was that those same draughts picked up much of the dampness that the cottage’s simple building materials had not been able to banish. Nowadays, without a permanent open fire but with expensive central heating, those useful draughts are often sealed up, and this might worsen a damp problem already made bad by incarcerating the cottage in modern waterproof paints. So all in all it would be better to keep modern materials and old cottages entirely separate. Except that in most cases it is too late (for some compromises see alsoChapter 11: Get It Right Next Time).

The ability of cottage construction to cope with slight movement has contributed to their visual interest. But while some cottages have changed shape slightly over time, a great deal of cottage construction was never capable of being straight, plumb or level in the first place. So cottages are not necessarily crooked or uneven because they are old and worn out – many were built that way. And that is why we love them.

New-fangled cracks

When an old house or cottage is being redecorated there are often cracks seen being filled that run from the corners of the windows and doors. This can be a symptom of cement render having been used at some time in the recent past: being relatively brittle, cement can crack in big squares as if it were thin, hard icing on a cake that has been bent. Traditional lime render, on the other hand, can accommodate little shifts in the building – more like marzipan.

Four in a row; cottage styles from several centuries happily side by side.

WHAT ARE YOU LOOKING AT?

It has been a long time since cottages were routinely repaired and redecorated using the very same materials with which they were built. It has been so long that even chocolate boxes, calendars and jigsaw puzzles now routinely feature cottages painted in ‘plastic’ paint in eye-watering 1970s colours, and with 1980s designs of windows and doors. Most of what is actually visible to our eyes could often be a late twentieth-century veneer entirely dependent on our oil-fired economy, with only the bare outline of the original hand-crafted cottage left.

Even inside, cottages have been stripped of original surfaces and their previously spartan interiors adorned with fitted carpets, fitted kitchens and fitted bathrooms. These upgrades are inevitable as many cottages originally had no floor other than bare earth, and certainly no bathroom or WC. In so many cases all that survives is a selection of carefully chosen ‘beams’ and a planked door or two, but even these are most likely pickled behind several coats of thick, gooey, suffocating modern varnish.

Pick on something else

Cottages are small and unsophisticated and therefore easily bullied by those who feel the need to gut an old building and fill its skin with reproduction antiquity or minimalist modernity. A cottage is more likely to be happy in its original skin if its insides are all of compatible construction technology.

There is obviously a practical balance that has to be struck between twenty-first-century living and pre-twentieth-century aesthetics. But if, as this book hopes to show, there are common-sense technical reasons to re-employ some pre-nineteenth-century finishes, then cottages could also benefit by looking much more authentic as a result. Nor should we forget that, in period properties, ‘authentic’, which equals historical worth, must sooner or later come to dictate financial worth. It has happened with other antique items, and who wants to be left with something that might have been more valuable if only it hadn’t been spoilt?

ON THE THRESHOLD OF A DREAM

I didn’t know it would be like this

Getting to know what an old cottage might be like to live in is very useful if you don’t already have that experience. A spell in a holiday cottage, perhaps run by one of Britain’s National Trust charities or one of the national heritage ‘quangos’, can be a useful introduction. Those people who are inclined to fret over creaking floorboards or doors that are not quite straight may take time adjusting to the reality of cottages; some places can appear a bit rough and ready, they can harbour a rich variety of wildlife and insects, and they will always, always, need some routine care and attention. In some ways a cottage is like a pet that needs constant attention – and it is never established quite who owns whom. But cottages have lasted much longer than pets or their owners, and will be around to influence future generations – today’s owner is merely one in a long timeline of custodians.

Make it easy on yourself

Once a cottage is chosen, it can be a very good idea to take time to get to know it, rather than immediately embarking on a regime of change. Having gone through the process of carefully choosing a cottage, then it should be mainly right for the occupants already – and if not, then perhaps the wrong cottage has been chosen? Cottages are individual, so try not to import prejudices from outside about decorations, alterations and fittings as soon as the keys are handed over. Even if it means living with the previous owner’s brown shag pile carpet and a classic avocado green bathroom suite for a few months, that time should be what informs how the place is going to work and what are its best features. If the cottage is not given a chance to show its best features, then those things could be inadvertently swept away. Unnoticed treasures, tricks of light, views – all gone forever. The same applies to the garden – and that ideally needs a full run of all the seasons to tell you everything it can offer. (See alsoChapter 2: The Professionals – ‘Timetables for work to older properties’, page 34.)

The idea of custodianship

Taking on a cottage in poor condition and returning it to health and beauty might leave some owners feeling that they have put in more effort than they are likely to see returned. But the repayment is partly in the satisfaction of passing on something of value to the future: there are few other projects that most people have the opportunity to initiate almost single-handedly which would improve the environment. The payback is not from the owner having imposed their will on a small building, but in having passed it on to the next generation with its genuine features intact and better equipped to survive. While there are always going to be surprise pitfalls, with proper information and appropriate help, preserving a cottage and returning it to a more sustainable balance can be satisfying, and a rewarding and lasting achievement. And it can make the country look a little bit better.

Roots

Owners can become involved in the history of their own cottage, and this can improve the experience of living there and help explain some of the things they may find while exploring the building. Historical local census returns can show the occupation of former occupants, local archives may have maps and records such as old farm and estate plans. General reading on the artefacts and customs of the period could also shed light on things found on the cottage, some related to the occupation of the householder, others of more general life. (See alsoChapter 6: Sticks and Stones – ‘Timber Frame – Further interest’, page 85.) This book tries to give a feel for the diversity of British cottage construction, but there is not space to catalogue every type – the variations are many, and almost every county has its own style, if not its own materials. It is worth finding out more.

Selection

The necessity for sustainability has brought to the fore the idea that we should preserve the ‘embodied’ energy and materials that were used long ago to create old buildings. So it makes environmental, not just financial, sense when buying a cottage to try to choose one that is suitable just the way it is. Avoiding alterations avoids wasting what is already provided, avoids the unnecessary use of energy and resources, avoids expense, and avoids further eroding whatever genuine antique fabric has actually survived from the past. Of course there will be the need to make repairs, maybe carry out some updating to plumbing and electrics, and possibly some selective adaptations: these are examined in the later chapters of this book (Sections Three and Four). Even though humans are intelligent enough to adapt to buildings, frequently people will embark on a costly programme of building alteration before they have allowed themselves time to work out how to use what is there more ingeniously and more economically.

Understanding old methods, and buyers’ surveys

This book aims to smooth the path towards a happy relationship between cottage and occupant, in part by explaining some of the common-sense logic of old buildings – logic learnt over a thousand years of building that has come to be forgotten and disregarded, sometimes with expensive and damaging consequences.

When setting out to buy a building, prospective owners are normally advised to get a full professional technical survey, not just a valuation, from a properly qualified surveyor. In the case of a cottage, its age will normally justify seeking a surveyor who is in addition experienced and accredited in conservation (the RICS www.rics.org organizes such accreditation for surveyors, the AABC www.aabc-register.co.uk for architects). This is because the modern building industry has moved on tremendously fast in the last hundred years and has forgotten most of the old-fashioned construction wisdom that was once everyday knowledge. If anyone is thinking of spending a substantial sum of money on something, then it makes sense to have it examined by someone who knows better than most how it was put together.

The next chapter introduces some of the professional and building skills that a cottage owner may need to engage, as well as looking at some of the implications of grants and taxes. Chapters 8: This Old House and 9: Reasons to be Careful look at a selection of common maintenance and hazard problems that could also be relevant for anyone who is looking at a cottage for the first time with a view to making it their home.

CHAPTER TWO

The Professionals

The right help when needed

PEOPLE

Unfortunately, cottages are unlikely to come complete with original plans and specifications or even an instruction book, and the owner would be lucky to have records of past alterations, even quite recent ones. So where does the owner turn to find help?

Horses for courses

A slightly crooked appearance is often considered to be part of a cottage’s charm, and it would be sad, or mad, to straighten it just for neatness. But who is to know when quirky crookedness is about to turn into dangerous off-balance? Who also can judge what grim decay might be lurking beneath the surface of an old cottage, even if (as can easily be the case with some modern materials that are wrongly used on an old building) the surface looks absolutely perfect?

Obvious

Everyone accepts that horses have horseshoes, and cars need rubber tyres. Likewise cottages can need to have distinctly different maintenance to modern houses. What is so difficult about that? But what often happens is that cottages are repaired and decorated with materials intended for modern houses. That is like nailing car tyres to a horse: neither will work properly afterwards. Sadly, there is still a widespread and misguided belief that modern maintenance is the best for old buildings.

Everybody may feel entitled to be a pundit on the subject of building, but as long as it remains an almost everyday occurrence to find potentially harmful things still being done to cottages and other old buildings, then experts need to be chosen with care. Regrettably, even ordinary respectable builders and professionals can still be found stripping off the original materials that are part of a cottage’s survival mechanism and replacing them with modern materials that fight it. They do this because they do not understand the way the old materials worked, and they also expect that the new materials and methods will work on an old building in the same predictable way that they are used to on a new building.

It’s building, but not as we know it

Superficial similarities between old and new construction have misled many owners, architects, surveyors, builders and decorators into assuming that not only can old buildings take all modern repair methods, but they can even benefit from them. It is now clear that this is not always the case. Old cottages are not modern houses and they were often intended to cope with damp and with movement in very different ways to modern construction. Modern finishes that seal cottages up and stop them ‘breathing’ can set off rot, while modern repairs that are too rigid can fail when old cottage fabric flexes naturally, as it must.

The experience gathered by builders and craftspeople over the centuries, the result of painstaking trial and error, was largely wiped away by the adoption of modern building methods during the twentieth century. Fortunately, traditional skills and design techniques are being re-established for conservation projects, and each link in the chain of the building team can now be made up from people with appropriate skills and experience. But they are not everywhere yet, so where to find them?

We still build with brick now, so what can be simpler than finding a bricklayer for repairs? But it can be surprising how much the search needs to be narrowed when looking for one who is comfortable using traditional lime mortar.

Where to look for expert help

Before selecting professionals and builders the cottage owner might usefully contact their local authority’s conservation officer to seek some local knowledge. The local authority might even be able to provide records of past planning and Building Regulations applications relevant to a particular property. A useful source of general information is the charity The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (www.spab.org.uk), whose members also have access to courses and facilities, and there is also general information on www.oldhouse.info.