Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

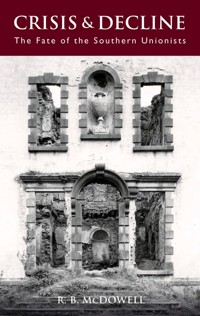

'Receding imperialism usually leaves behind those who have for generations staunchly upheld its authority and flourished under its aegis – Germans in Bohemia, Swedes in Finland, loyalists or tories in the American colonies, Greeks in Asia Minor, Muslims in the Balkans. Among those abandoned adherents of a lost cause were the unionists in the south and the west of Ireland.' So begins R.B. McDowell's preface to this lively, meticulously researched account of the fate of Irish unionists outside Ulster from the era of Parnell through the early years of the Irish Free State. McDowell details the efforts of a ruling minority to maintain the union between Britain and Ireland, and tells the story of what became of them during and after the Anglo-Irish war and the handing over of the twenty-six counties. The bastions of Southern unionism – Trinity College Dublin, The Irish Times – come under sympathetic scrutiny from a man who became intimately acquainted with the ex-unionist world while a student at Trinity in the 1930s, as chronicled in the colourful Afterword. Crisis & Decline also records the testimony of ordinary unionists – farmers, shopkeepers, policemen, and others – who sought compensation for losses suffered during the 1920s. McDowell gives us a nuanced portrait of a distinctive social group, much mythologized in literature but hitherto neglected by historians, who clung steadfastly to a doomed vision of Ireland within the British Empire. Originally published in 1997, R.B. McDowell's pioneering study of Irish unionism is now being reissued in paperback by The Lilliput Press.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 424

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Crisis and Decline

TheFateoftheSouthernUnionists

R.B. McDowell

THE LILLIPUT PRESS Dublin

Contents

Preface

RECEDING IMPERIALISM usually leaves behind those who have for generations staunchly upheld its authority and flourished under its aegis – Germans in Bohemia, Swedes in Finland, Loyalists or Tories in the American colonies, Greeks in Asia Minor, Muslims in the Balkans. Amongst those abandoned adherents of a lost cause were the unionists in the south and west of Ireland. From the time Home Rule became a serious issue in politics they strove to maintain the union enacted in 1800, and once the Treaty was signed they had either to emigrate (a depressing and costly option adopted by comparatively few) or adapt themselves to the new political environment. Of those who stayed on in the Irish Free State, some went into internal political exile, while many contrived to play an active part in the economic and social life of the country. All retained principles, prejudices and loyalties which challenged the preconceptions of contemporary Irish nationalism.

A community that had for so long played such a conspicuous and powerful role in Irish life and that, even in its decline, remained a distinctive and to a limited extent influential element in the south and west of the country, undoubtedly merits a measure of attention, at least on the level of a short study. Moreover, departed greatness tends to exercise a profound, uncanny fascination, encouraging in some a stern or sour belief that history inevitably metes out social justice; arousing in others a melancholy sense of loss –

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Ninevah and Tyre

– and reminding many of the transitory nature of things –

My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

After I entered Trinity College, Dublin, in the early thirties, I moved in the ex-unionist world, enjoying its hospitality and imbibing its opinions and prejudices. Naturally, then, when working on Irish history of the first half of the twentieth century I have been repeatedly reminded of controversies, battles and personalities glimpsed from a distance long ago. Memory, I hope, has been at times a help in illuminating the results of research. However, to avoid being over-obtrusive, I have relegated my recollections of public affairs (the recollections of a person of no importance) to a section following the final chapter.

Acknowledgments

I AM GRATEFUL to Dr David Dickson for most helpful advice and criticism, and to other sometime colleagues in the Modern History Department, Trinity College, Dublin, for their encouragement. From Dr Elizabethanne Boran and Miss Olwen Myhill I have received valuable assistance. I must thank the Deputy Keeper of the Records, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, for permission to use the material in his custody, and I am greatly indebted to the staffs of the libraries and repositories in which I have worked for the facilities and help they have readily afforded me.

I Sanior Pars

DURING THE HOME RULE CONTROVERSY those who were advocating any degree of political autonomy for Ireland had to contend with one difficulty: the fact that a substantial number of the inhabitants of the country were not, in the political sense of the term, nationalists. About the beginning of the twentieth century unionists optimistically asserted that roughly one-third of the population supported the maintenance of the union. Admittedly this was a minority, but it was certainly a potent one, comprising, it was said, ‘all that is best in Ireland, her enterprise, her industry, her intellect, her culture, her wealth’ and, it might be added, ‘the backbone … and the fighting power of the country’. The Unionist party, a party distinguished by quality if not quantity, was the party of education and property – demonstrated for instance by an analysis of the reception committee of the great 1887 Dublin unionist demonstration: 101 deputy lieutenants and JPs, 124 barristers, 65 physicians, 28 fellows and professors of Trinity, the governor and directors of the Bank of Ireland, 34 directors of public companies and 445 merchants.1

The Irish unionists, at least 1,100,000 strong in 1914, were divided by geography, history, economic developments and religious demography into two sections, the Ulster or Northern unionists and the unionists in the other three provinces, the former centred on Belfast, the latter on Dublin. In estimating the numbers and distribution of Irish unionists the denominational statistics provided by the Irish census are exceedingly helpful, bearing in mind that generally speaking Protestants were unionists and Catholics nationalists. The fastidious might deplore confounding the spiritual with the secular, but many keen partisans would, at least as regards their own side, regard this as a happy coincidence of religious and political virtue.

However, other strong but more broad-minded party men wanted their cause to be comprehensive rather than sectarian. Some intelligent unionists, anxious to prove that the union was widely recognized as most beneficial to Ireland, eagerly welcomed Catholics to their ranks. W.E.H. Lecky, for instance, once wrote, ‘I have never myself looked upon Home Rule as a question between Protestant and Catholic. It is a question between honesty and dishonesty, between loyalty and treason, between individual freedom and organised tyranny and outrage.’2 Nationalists were insistent that all Irishmen were in essence nationalists. It was only blind prejudice, narrow self-interest or invincible ignorance that prevented unionists throwing in their lot with their nationalist fellow countrymen. Wolfe Tone, regarded as one of the fathers of Irish nationalism, had expressed the wish to substitute the common name of Irishman in the place of the distinction of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter. Tone of course was a man of the Enlightenment. Nineteenth-and twentieth-century Irish nationalists were faced with the problem of reconciling the liberal approach to religion and politics with the undeniable fact that, since the overwhelming majority of nationalists were Catholics, Catholicism and nationalism were closely intertwined. For many, indeed, Catholicism was an essential component of Irish nationalism. Nationalists seem to have solved the problem by assuming that for a Protestant nationalist, his Protestantism was a matter of assenting to certain dogmas and forms of worship and would not seriously affect his feelings and thinking about Ireland. But an Irish Protestant derived much of his religious tradition from England and Scotland, the Authorized Version and the Shorter Catechism being important elements in his heritage. Naturally then, the great majority of Irish Protestants were biased in favour of the British connection. There were, however, a small number of Protestants who, out of the belief that the union was crippling Irish development, enthusiasm for the Gaelic past and the Home Rule future, generosity of spirit or sheer crankiness, were nationalists – ‘rare birds’, according to Carson, whom the nationalists were ‘fond of exhibiting’. Or, as the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh declared, ‘a stage army’, exploited on every occasion.3 The Protestant nationalists included some distinguished figures such as Yeats, George Russell, Stephen Gwynn, a man of letters who became a nationalist MP, Shane Leslie, a convert to Catholicism, and T.W. Rolleston, ‘an aristocratic nationalist’. Rolleston admired the high-mindedness of Sinn Féin in its early days, denounced the Irish parliamentary party as ‘a damnable gang of swindlers’ and defended Lord Clanricarde’s dealing with his tenancy. He was both a strong Home Ruler and a fervent imperialist. ‘Let us’, he wrote, ‘while steadily urging our national demands, at the same time claim and hold that place at the centre of authority of the Anglo-Celtic empire which the facts of physical nature, of race and of history have assigned us.’ Irishmen, he was convinced, had qualities – broad-mindedness and a sympathetic awareness of differing opinions and interests – that fitted them to play an influential part in imperial affairs.4

Catholic unionists were more conventional and probably far more numerous than Protestant nationalists. They included landlords, soldiers, lawyers, and a fair number of resolute supporters of law and order, some who were instinctively conservative and others who were unimpressed by the case for Home Rule; or, as a unionist pamphleteer put it, ‘all the Irish Roman Catholic gentry (except Sir Thomas Esmonde), three-quarters of the Roman Catholic professional men, all the great Roman Catholic merchants and half of the domestic class’.5

Catholic unionists may have deplored and even have been disconcerted by the way in which the Irish Catholic clergy tended to identify Catholicism with Irish nationalism, their emphasis on ‘Faith and Fatherland’. But Catholic unionists could console themselves by reflecting that through much of history and over much of the contemporary world the Church was a conservative force, upholding the status quo, ready to defend property and the existing order so long as the state abstained from attacking ecclesiastical rights. As Lord Fingall said at a great unionist meeting, ‘if Catholicism had any political tendency it was rather towards the maintenance of the union’.6

Working on the assumption that denominational and political loyalties closely coincided, the Irish unionists fell into two sections, the Ulster unionists and the unionists in the other three provinces. But by the beginning of the twentieth century this line of division was found to be imperfect. Though the unionists definitely predominated in some parts of Ulster, in the province as a whole they outnumbered the nationalists by a very narrow margin, so when the question of excluding the North from the jurisdiction of a Home Rule parliament in Dublin arose, it was ultimately decided that ‘political Ulster’7 should be the six north-east counties. Therefore it is convenient when discussing the Southern unionists statistically to consider them as being the unionists in the three southern provinces together with those in Counties Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan (twenty-six counties in all).

In 1914, of the 1,100,000 Protestants in Ireland 327,000 were in the twenty-six counties, amounting to slightly over 10 per cent of the population of that area. Their distribution was highly erratic. In the city of Dublin under a fifth of the population was Protestant; in the three townships of Kingstown, Pembroke and Rathmines and Rathgar and the rural districts of Blackrock and Dalkey, prosperous sections of the Dublin built-up area though outside the city boundaries (and determined to remain so, their inhabitants being on this issue Home Rulers), Protestants amounted to over 60 per cent of the total population.8 In the city and county of Dublin combined, Protestants (numbering 101,000) formed slightly over 21 per cent of the population. Protestants amounted to 17 per cent of the population of County Kildare and 21 per cent of the population of Wicklow, so that a new ‘pale’, the city of Dublin and the neighbouring counties, included 127,000 Protestants, about one-third of the Protestants in the twenty-six counties. Another 70,000 were to be found in the three Ulster counties, where, as might be expected, there were substantial Protestant minorities – in Donegal 21.5 per cent of the population, in Monaghan 25.32 per cent, in Cavan 18.54 per cent. All this meant that there were comparatively few Protestants to be found in the rest of Leinster, Munster and Connacht. In Leinster minus the ‘pale’ they were just under 9 per cent of the population, in Munster 6 per cent (rising to almost 9 per cent in County Cork) and in Connacht under 4 per cent. In three urban centres they were comparatively numerous – in Cork 11.56 per cent, in Limerick 9.48 per cent, in Sligo nearly 9 per cent.

If the Southern Protestants’ geographical distribution was distinctly uneven, the social composition of the community, as shown by the occupational tables included in the census, was remarkably top-heavy. In the twenty-six counties almost half the lawyers (a shade under 48 per cent), well over one-third of the medical men (37.7 per cent) and almost half the surveyors and engineers were Protestants. Turning to business, over one-fifth of the merchants (21.9 per cent), over 70 per cent of those engaged in banking, half the accountants, almost half the auctioneers and nearly one-third of the commercial clerks were Protestants. On the other hand only 7.4 per cent of farmers and 2.7 per cent of farm labourers and farm servants were Protestants.

Though the numbers of Protestant farmers (something over 21,000) and farm labourers (4000) in the twenty-six counties were relatively small, the Southern unionists could claim they had a substantial number of farmers (at least 21,000) in their ranks. These together with a sprinkling of farm labourers, servants in ‘big houses’, landlords’ men, Protestant small shopkeepers, urban artisans and police and military pensioners, who all prided themselves on being supporters of the union, afforded some justification for asserting that Southern unionism embraced all classes in the community. That the party was both socially inclusive and had a strict sense of social propriety was demonstrated at a great Dublin anti-Home Rule meeting held in the Rotunda. The body of the hall, it was reported, was almost filled by artisans and working men while members of the aristocracy and professional and mercantile men occupied the platform.9 Shortly afterwards the Dublin Conservative Workingmen’s Club emphasized class interdependency, calling on the government to take steps to restore to the landed interest ‘their former capacity for employing the industrial classes’. The Club was strongly of the opinion that to avoid the struggle forced on them by the enemies of law and order would be ‘to brand ourselves as moral and political poltroons’.10

The most conspicuous element in Southern unionism was the landed interest, peers, and baronets resident in Ireland and the landed gentry, the class which, according to a eulogist, formed ‘the backbone of the country’ from which had sprung Ireland’s ‘most distinguished sons’.11 There was, another eulogist wrote, ‘good stuff’ in the descendants of ‘the toughest breeds of the old Irish race’ and of ‘the hardier and more adventurous spirits of Great Britain or of a cross between these stocks’.12

Though the landed interest was clearly discernible, and in any neighbourhood there would be general agreement as to which families belonged to it, membership was not precisely defined. What made a landed gentleman was not merely the possession of landed property but rather varying combinations of birth, acreage, upbringing, profession, life-style and, very occasionally, the determination to be recognized as one. It would be impossible to state statistically the size of the landed world but a rough guide to membership is provided by the Commission of the Peace. The head of an established landed family almost automatically became a JP (and in each county about twenty landowners were appointed deputy lieutenants, an additional acknowledgment of their status). In the 1880s approximately 2690 JPs described themselves as a landlord or landowner (about 2270 in the twenty-six counties). Therefore the Irish landed world could be taken to number a few thousand families.13 Of course younger sons were to be found in the Church, the services and the law, and daughters sometimes married non-landed men, so many people all over Ireland cherished a connection, even if distant, with an indubitably landed family.

An Irish landlord was usually doubly a man of affairs – both managing his estate and taking part in public life as a JP, a poor-law guardian, a grand juror or a militia officer. An estate was, it has been said, ‘a local industry’,14 with indoor and outdoor servants, bailiffs, gamekeepers and rent warners. Beyond the demesne walls there were tenants to be conciliated, encouraged, rebuked or on occasion evicted, and the landlord or his agent had to be familiar with ‘files, rentals, ledgers and rent rolls … head rents, ground rents, gale day and hanging gales, turbarys, free farm, fee farm and first, second, third term rent decisions’.15 There were instances, fortunately comparatively rare, when a landlord involved in acute agrarian conflict might have to live under police protection, almost in a state of siege – the stresses and strains that might be sustained by a boycotted family being vividly portrayed in two novels of the early 1880s, TheLandleaguers by Trollope and ABoycottedHousehold by Letitia McClintock, the daughter of a County Donegal landlord.

A landlord’s economic and social status was clearly indicated by his residence, ‘the big house’, with outbuildings, gardens and plantations. Until early in the twentieth century these houses (and their equivalents elsewhere in Europe) were taken for granted; in fact to the hundreds scattered through Ireland, built on classical lines, there were added during the nineteenth century a number of Gothic mansions – suggesting a sublime unawareness of the impending land acts. Later, between 1921 and 1923, a number of Irish country houses were destroyed and others fell into ruin with the departure of their owners. Ireland in the 1930s, it was remarked, was covered with dilapidated mansions with ‘unpainted and rusting gates and grass-covered drives’.16 An extreme nationalist dismissed these as ‘big garks of country mansions’, built by a wastrel, spendthrift, rack-renting ascendency.17 But in England there was a growing nostalgic interest in eighteenth-century architecture and in a way of life ‘emphatically rejected in practical affairs’ – ‘there was never a time when so many landless men could talk at length about landscape gardening’.18 This vogue spread to Ireland. The big house began to be seen as the embodiment of aesthetic values, grace, balance, craftsmanship and sensitive planning, and its past occupants were seen through a romantic haze, enjoying elegant leisure and indulging in delightful eccentricities. With the pre-1900 agrarian system receding into the distant past, Irish landlords became associated, not with harsh estate management, but with the creation of an architectural heritage that enriched the countryside, gave pleasure to people of sensibility and was an asset to the tourist industry.

Though the Irish landed world was sometimes viewed in a Leveresque light as being composed of hard-riding, rollicking eccentrics, a country gentleman with a strong sense of history pointed out that at the end of the nineteenth century the great majority of the Irish landed gentry were as ‘sober, orderly and perhaps as dull as those who lived in England’.19 The Anglo-Irish gentry, a member of the landed world explained, were endowed with a combination of ‘levity and pessimism, of conscientiousness and good-natured laxity, of practical benevolence and abusiveness and of courage’.20 They saw themselves contributing not only moral stamina but culture to Irish life. Landlords and ex-landlords, a County Longford country gentleman asserted, formed ‘oases of culture, of uprightness and fair dealing in what otherwise would be a desert of dull uniformity’.21 In all this there was perhaps a trace of excessive self-satisfaction. Still, in a deferential age, when a vast number of middle-class men and women aspired to be regarded as ladies and gentlemen and assiduously tried to practice the manners and rules of good society, the landed gentry were respected and looked up to as social exemplars, even by those who might differ from them in politics.

It goes without saying that the gentry were, with rare exceptions, staunch unionists. A hundred years earlier many of the leading landed families had been eager to win and preserve Ireland’s legislative independence. But the parliament they had admired and cherished was one in which the landed interest preponderated. Circumstances had changed, and the imperial parliament was viewed as more likely to respect the rights of landed property than a Dublin assembly controlled by the representatives of a restive tenantry. Those landlords who were Protestants (the great majority) preferred to be in the United Kingdom than in a Home Rule Catholic Ireland. Finally, they were often connected with England by family ties, education and service in the forces, and shared many of the loyalties and prejudices of their English equivalents.

During the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century the Irish landlords possessed power and prestige. No doubt they had their critics, but it was taken for granted that they were an essential and permanent part of the Irish agrarian system and would continue living ‘an ordered, dignified existence in their big old-fashioned houses’, enjoying in their own orbit ‘power, leisure and deference’.22 Throughout the debates on the Land Act of 1870 it was assumed that, with some adjustments, the landlord-tenant relationship would continue to function successfully for the foreseeable future. But in ten years it had become conventional political wisdom that agrarian relations in Ireland were so unsatisfactory that the landlord must be removed from the system. As early as 1883 a future Conservative prime minister, Arthur Balfour, was advocating legislation to promote on an extensive scale the creation of a peasant proprietary, and two years later, Ashbourne, an Irish Lord Chancellor and a pillar of the Conservative Party in the Lords, was responsible for a land-purchase act, the first of a series which culminated in the Wyndham Act (1903), ‘that great treaty between rival agrarian interests in Ireland’.23 The Wyndham Act embodied a scheme of land purchase that proved acceptable to both landlords and tenants, one feature of the scheme being that the bonus on the purchase price paid to the landlord came out of the imperial exchequer.

At the time they were being prised from their estates (at a price), the Irish landlords were also rapidly losing political power and influence. The Reform Act of 1884, enfranchising the rural householder, placed electoral power in most constituencies in the hands of the small farmers and labourers – ‘the hovel electors’, to quote one conservative – who, though they had many virtues, were ‘ignorant, excitable and prejudiced’ and absolutely unused to the duties and responsibilities of public affairs.24 From 1885 onwards in the south and west a landlord, unless he was a Home Ruler, had little or no chance of winning a seat. In 1898 the gentry lost control of county government. The Local Government Act of that: year, which Lecky called ‘a great and perilous experiment’ and glumly accepted as a political necessity, transferred local administration from the grand juries, landed oligarchies, to elected country, urban and rural councils. A landed gentleman could still expect to be a justice of the peace, but he had to rub shoulders with the chairmen of county and district councils who were ex-officio JPs, and the bench had already been diluted by the government’s efforts to conciliate public opinion by granting the Commission of the Peace to, in the words of a strong unionist, ‘persons possessing the confidence of the peasantry … substantial, or let us say the less insubstantial small farmers’. He consoled himself by reflecting that ‘the Irish rustic’, though he will always have a certain ingrained respect for ‘the quality’, would have only contempt and distrust for ‘“Doran JP”, who is little more than his equal’.25

At the beginning of the twentieth century the Irish landlord was an endangered and disappearing species. A sympathetic observer, George A. Birmingham, painted a pathetic picture of an Irish country gentleman, excluded from local affairs, if listened to politely, gazing from a window in his ‘stately home’ over a broad stretch of country and sighing, ‘it is mine no longer’.26 Birmingham, though a humourist who delighted a large readership by dwelling on the absurdities of life, especially Irish life, was fundamentally a serious-minded man who sadly concluded early in the twentieth century that there ‘was no place in Ireland nor anywhere else for the gentleman in human affairs’ (in 1922 he left Ireland and settled in England).27 About 1913 ‘country gentlemen of moderate fortune’, it was said, were migrating to the Dublin suburbs and seeking ‘occupations which would provide a living wage for a man of refinement and good traditions’.

But there was another, less dramatic side to the picture. Land purchase could leave a landlord with his house, a fair acreage (demesne and home farm) and a chunk of liquid capital. He could still enjoy sporting and social life, and when he felt an urge to participate in public life he could be active in the Unionist Alliance or attend the General Synod. It is not surprising, then, to find that in the 1912 edition of Burke’s LandedGentryofIreland the head of nearly all the families included is still recorded as residing in the traditional family seat. After all it was generally agreed, at least among public-spirited men who were connected with the landed world, that once the old agrarian system had been swept away, the sometime landlords would continue to play a stimulating and valued role in rural Ireland. John Redmond, when supporting the Local Government bill of 1898 and Wyndham’s Land Purchase bill, expressed the hope that there would be ex-landlords (he was about to become one himself) who would remain in their own country and take part in the management of its affairs. It would be ‘monstrous’, he said, if men who had an aptitude for county business were excluded on narrow sectarian or political grounds. Irish landlords, Colonel Saunderson, a leading Southern unionist, assured the House of Commons, were very anxious to live ‘in our own native land … we are Irishmen as much as the tenants are … we love our nation as much as they do’, and, far from sulking, they would readily offer themselves for election to local bodies.28 Horace Plunkett, concerned with economic regeneration, argued that if Ireland was to become a land of small farmers, it was undoubtedly desirable to have scattered through the countryside ‘a certain number of men possessed of education, wealth, leisure and the opportunity for study and travel’. The sometime landlords, living on their demesnes and home farms, could introduce improved agricultural techniques and strive to make the country culturally alive – for example as a start arranging magic lantern lectures.29 Another country gentleman, having pointed out that the gentry were near enough to the people ‘in racial sentiment to understand and sympathize with their national aspirations’, but ‘remote enough to command their respect’, wanted the gentry to both encourage cultural activities and battle against corruption in public life – unfortunately, he wrote, politics to the average Irishman was just a game.30 The nationalist MP Stephen Gwynn, himself of landlord stock, reflecting in 1909 that Ireland had lost half her gentry, ‘a great loss’; he too wanted the gentry to play an active part in a Home Rule Ireland, though he warned them it would be a democratic Ireland and that ‘they must take their chances in the ruck’.31 An optimist could even hope that with land purchase the legitimate political influence of the resident gentry would be revived and that their ex-tenants, converted into owner-occupiers, instinctively attached to the status quo, would vote unionist. But an experienced civil servant, who knew Ireland well, warned unionists who said they found farmers in the South indifferent or even hostile to Home Rule, that they should ‘make allowance for the amiable tendency of the Celt when off the platform to say what will please’.32

With the Wyndham Act in operation it was hoped that land would cease to be an embittering issue in Irish politics. This, however, was not the case. Though at first land purchase under the act proceeded briskly, some landlords (especially those with heavily encumbered estates) were reluctant to sell out; there were tenants, probably hoping for a further reduction in rents, who hesitated to buy; and trends in the stock market made it harder to finance land purchase. The result was that land purchase slowed up, and by 1914 the process of transforming the tenants into owner-occupiers was only about two-thirds of the way to completion. There was also the problem of evicted tenants, in the words of a nationalist MP ‘the wounded soldiers of the land war’; ‘loafers’, according to a unionist MP, who should not be benefited at the expense of honest tenants who were being denounced as ‘land grabbers’.33

By 1914 the Estates Commissioners had managed more or less to reconcile the claims of these two categories but bitter memories festered. Then, in the post-Wyndham era, the Irish land question emerged in a new guise. While many tenants were happily purchasing their holdings, land hunger was growing among landless labourers and poor farmers on uneconomic holdings. This appetite, it was felt, might be satisfied if stretches of grazing land, let on short leases by large farmers and landlords, were acquired by compulsory purchase at what agitators considered was a fair price and divided amongst the landless. To compel ranchers to sell and deter graziers from taking lands on short leases, boycotting, cattle-driving and other forms of intimidation were employed. A number of the landowners who were the targets of agrarian agitation were unionists, and Southern unionists in general were shocked to see, in the words of James Campbell, a hard-hitting lawyer and MP, the law of the land ‘paralysed’ in parts of the south and west.34 Campbell may have exaggerated, but the disturbances reinforced a basic unionist conviction, that in a country prone in the south and west to lapse into agrarian violence the unionists were consistent and courageous supporters of law and order, in contrast to the nationalists, who either tended to be passive or even to condone extra-legal behaviour – a bad augury for what would happen under Home Rule.

Strong convictions, readily and confidently expressed, were a characteristic of Southern unionists, but unfortunately a systematic exposition of their political creed was never published. In their ranks were a number of men and women of intellectual power – Ashbourne, Atkinson, Elrington Ball, Richard Bagwell, Edward Dowden, C.L. Falkiner, John Healy, Emily Lawless, Lecky, David Plunket, E.O. Somerville – but in their writings and speeches they restricted themselves to dealing with immediate issues, making penetrating comments on the play of events but touching only briefly on general principles. Nevertheless their political beliefs are easily perceived and outlined. The Southern unionists profoundly believed that the union of Great Britain and Ireland was of the greatest value politically, economically and culturally to Irishmen. It enabled Ireland to share in the councils, activities and thought of three other historic communities: the English, the Scots and the Welsh, the four nations working happily together with each preserving its distinctive qualities and traditions, the United Kingdom demonstrating how much vigorous variety could flourish within a common political framework. Irishmen gained immensely from being able to participate fully in the many-sided life of the United Kingdom.

Moreover, the United Kingdom was the keystone of a mighty empire, ‘a great worldwide bond of English-speaking men’, which meant not only ‘wealth and power for England but freedom and happiness for all that lived under the protection of the imperial flag’.35 Nor, as Irish unionists were quick to stress, should the Irish contribution to Great Britain and the empire be overlooked. Catalogues of names could be recited – soldiers, Wellington, Wolseley, Gough, Roberts, or administrators, Wellesley, Hastings, Mayo, or men of letters, Swift, Burke, Goldsmith. Ireland, it was asserted, brought three valuable strains into British and imperial life: the Celtic, with a dash of audacity, the practical and constructive Anglo-Irish intellect and the Scottish, ‘more solid than brilliant’.36 It appeared to intelligent young Southern unionists that at the opening of the twentieth century the Anglo-Irish or the unionist element was ‘the most vital creative force’ in the country. To them Irish nationalism was ‘a morbid inflamation which sought to reject not only British civilization but world culture and progress’.37

Ireland, it was continually argued, had prospered under the union. It was better for Irishmen to be seated at Westminster than in ‘a pettyfogging assembly in which Parnellite may squabble with anti-Parnellite over the water and gas in Skibbereen’. A vast amount of beneficial legislation for Ireland had been passed by the imperial parliament. ‘What’, a fellow of Trinity asked, ‘has the United parliament left for an Irish parliament to do?’38 Also, an imperial parliament and government could view Irish problems in a broad perspective and hold the balance fairly between contending sections – a vital matter for Southern unionists, who for all their self-assurance were a small, scattered minority.

The disadvantages of belonging to a minority, more especially a ci-devant privileged minority, were brought sharply home to unionists by the workings of the Local Government Act of 1898. In 1911 it was reported that of 707 county councillors in the three southern provinces only fifteen were unionists, and this almost certainly meant that unionists stood a poor chance when local government appointments were being made.39 Of course, it could be argued that nationalist voters could scarcely be expected to elect as their representative an avowed unionist. As Lord Mayo explained in the House of Lords, when he stood for a district council ‘he was told, “If you say you are a Home Ruler we will elect you at once” and of course I said I would not have anything to do with it.’40 As regards local patronage Patrick Foley, the Catholic Bishop of Kildare, approached the question in what he obviously thought was a reasonable way. ‘Until’, he said, ‘the balance of disadvantage which told against Catholics in the past was fully redressed, the question of justice to all parties, on the principle that the endowments as well as the burdens of citizenship should be evenly distributed, could not arise.’41 Fair enough in the Bishop’s opinion. Nevertheless the disappointed unionist applicant (in his own eyes well qualified) may well have thought it inequitable to make him pay for his putative progenitor’s good fortune.

Apprehensive unionists could of course be reminded by the advocates of Home Rule that it did not repeal the Union but merely modified it. Under the bills of 1886, 1893 and 1912., Westminster and the British government would still exercise a considerable degree of influence in Irish affairs. Such a division of powers and functions, unionists retorted, would be administratively and financially almost unworkable. Moreover, unionists, especially Irish unionists, continually dwelt on a much more fundamental objection to Home Rule: that it would be merely a prelude to complete separation from Great Britain. Once an Irish parliament and an Irish executive were established in Dublin they would be continually striving for further concessions (‘no man’, Parnell had declared, ‘had the right to fix the boundary to the march of a nation’) until Ireland obtained complete independence. If Home Rulers denied this they were either deluded or intent on hoodwinking the British public.

Fervently loyal to the union and the empire, Southern unionists were at the same time very conscious that their homes were in Ireland. It was the Irish landscape, Irish streets, roads and railways and the Irish climate that provided the background for their diversified activities. Bound to Ireland by ties of friendship and family and by institutional loyalties, it was there they had their property and their careers and enjoyed a way of life that was often very tolerable. ‘I hate leaving my country,’ an ultra-unionist Galway landlord wrote in 1920, ‘there is no country like it, if it is properly governed – I am fond of stock breeding and there is no property in the British Isles like this for it’.42 Referring in Hurrish to a fictional Irish landlord, Emily Lawless remarked, ‘the sense of country is a very odd possession, and in no other country is it odder than in Ireland. Soldier, landlord, Protestant, Tory of Tories as he was, Pierce O’Brien was at heart as out-and-out an Irishman as any of his tenants.’43 These feeling are warmly expressed in some artless verses by two members of a County Clare landed family:

I am only a poor West Briton

And not of the Irish best

But I love the land of Erin

As much as all the rest

I love the blue clad highlands

Blue rimmed with sunset low gold

Each ruined tower recalling

The days and scenes of old

But our little western island

Could never stand alone

And we share the greatest empire

That the world has ever known

To Celt and Scot and Saxon

That empire was decreed

’Tis guarded by Irish solders

Who fight in Britain’s need.44

Southern unionists were well aware that they had wider loyalties as well as Irish ties and traits, but only in very rare instances does this seem to have caused distressing emotional or intellectual tension. Strong local affections and a commitment to the United Kingdom could for Southern unionists co-exist happily enough. To them, it was said, ‘Ireland was a country not a nation’.45

To an Irish nationalist this attitude was anomalous if not outrageous. Irishmen, nationalists asserted, shared historic memories, material interests, ideals and aspirations. Ireland therefore was a community indubitably entitled to political autonomy, and people in Ireland who did not accept this were self-proclaimed aliens. To unionists, both in Great Britain and Ireland, this was an over-simplification. Nationality was a complex compound and it should not be held as axiomatic that a community possessing a sense of nationality required for its expression political independence. There were many communities, including the Scots and the Welsh, having the ‘notes’ of a nationality, that were content to be included in a large sovereign state. In addition, unionists contended that Ireland was a divided country, inhabited by more than one race – the term ‘race’ being used to denote a group intensely conscious of its traditions and outlook – and optimistic unionists hoped the time would come ‘when the enlightened intelligence of the subject race or people’ would see ‘the advantages of the once-hated rule’ and become reconciled to it.46

Conscious of belonging to a distinctive, vigorous, self-assured if small community, leading Southern unionists from time to time attempted to explain tersely how they were able to harmonize their dual loyalties, attachment to Ireland and a profound belief in the value of a close union, cultural as well as political, between Ireland and Great Britain. Edward Dowden, Professor of English in Trinity, in 1886 expressed it succinctly: unionists, though friends and lovers of England, were ‘not the least faithful friends and lovers of this island of our birth’.47 Earlier, in the seventies, at the very beginning of the long struggle for the union, the eloquent John Thomas Ball, MP for Trinity and later Irish Lord Chancellor in Disraeli’s second administration, answering in the House of Commons the question, ‘What had Ireland gained by the union?’, replied, ‘a participation in your greatness, to be sharers in your glory, the opportunity of being one and the same with you’. His aim was, he said, to raise his country to the British level and to eliminate, at least in the legislative sphere, differences between the two islands. Incidentally he regarded the bulk of the population of Ireland to be, like the old Gaels, ‘an enthusiastic, susceptible and credulous people’.48 Some ten years later, in 1886, a Tipperary landowner told a unionist meeting that ‘they had a special local duty to Ireland’ but he ‘denied that England was not their country as well’.49

David Plunket, who confessed himself to be an Irishman born and bred, ‘all of whose traditions and recollections of happier times are associated and intertwined with Ireland’, endeavoured to distinguish between two schools of Irish patriotism. There was the old school of Irish nationalism, with ‘its passion, poetry and real self-sacrifice’ but romantic and impracticable. Then there was another school of patriotism, whose adherents were no less devoted to our country and its people, which ‘desires to see them preeminent and successful within the limits of an empire they have built up’. Theirs was a patriotism that saw no shame ‘in submitting to a parliament and an imperial power of which it is in itself an integral element and in whose greatness it has played a glorious part’.50 Another successful lawyer and Trinity MP also contrasted the two forms of Irish patriotism. There was, he said, the understandable patriotism that wished to see Ireland an independent nation, and there was the other form of patriotism, ‘as pure and worthy but infinitely more sensible and sound’, which saw no dishonour in binding Ireland to her ‘greater and stronger sister’. Ireland could under the union with Great Britain enjoy her freedom, be helped by her riches and join with her in making her laws, marching forward in her progress and in upholding ‘the sceptre which sways her mighty empire’.51

An invigorating element in the Southern unionist outlook, especially strong among landed and professional people, was a comforting sense of superiority. They adopted a dehautenbas attitude to their nationalist neighbours; political tact muted their comments on their Ulster fellow unionists, whom they found dour and unpolished. To Southern unionists, whose political and social centre was Dublin, Belfast seemed an upstart creation of industrial power, dull and dreary, lacking distinguished public buildings and sadly deficient in culture and joiedevivre – yet, it had to be granted, virile and expanding. Even the English, with whom the Southern unionist felt so closely akin, were open to criticism. The regrettable fact had to be faced that many Englishmen supported Home Rule and that there were English conservatives who were so eager to kill Home Rule by kindness that they acted on the principle that it was better to please your enemies than to do justice. Also, some Englishmen were sadly deficient in savoir-faire. For instance, in Emily Lawless’s Hurrish, Pierce O’Brien, a Clare country gentleman, thinks an RIC inspector, son of ‘a well-to-do London tradesman’, to be ‘consequential and underbred with a cockney accent’, and Lady Naylor, in Elizabeth Bowen’s TheLastSeptember, is struck by how shallow English people are and how hard to ‘trace’: ‘practically nobody who lives in Surrey seems to have been heard of, and if one does hear of them they have never heard of anyone else who lives in Surrey’.52

Of course it could be said that Pierce O’Brien and Lady Naylor condemned the inspector and the unfortunate inhabitants of Surrey not because of their national characteristics but because they were not, to use an old phrase, out of the top drawer. Two other Cork gentlewomen, Somerville and Ross, wrote that when they came in contact with middle-class English people they learned a lesson in ‘honesty, level-headedness and open mindedness’,53 but Major Yeats, an intelligent, good-natured and gentlemanly Englishman in thir IrishR.M. stories, is frequently baffled by the mental agility and social ingenuity of the Irish rural world, gentry and country people alike.

Southern unionists felt that, owing to circumstances, they had developed qualities that the stolid English often lacked. England’s faithful garrison in Ireland, living, working and keeping on reasonably good terms with their neighbours in an acutely divided country, had learned that it was politic to take into account even absurd social susceptibilities and that authority must often be exercised with tact and good humour. ‘The Englishman’, a Southern unionist MP wrote, ‘in a clumsy, blundering way is making the world a better place to live in …. Dogged, stupid, if you like, he is doing great work. But he lacks understanding and that is what we Irish can give him …. If we live for ourselves alone we betray our destiny.’ And another fervent admirer of the Anglo-Irish explained that their open-mindedness made them ideal cosmopolitans and enabled them to add ‘a useful and truly imperial tinge to the British rule’ overseas.54 Southern unionists were very conscious that they both dwelt in the empire’s heartland, the British Isles, and as members of a loyal minority were stationed on the imperial limes. Significantly enough, the conception of Empire Day (24 May), a day dedicated to reminding citizens of the empire of their duties and responsibilities, was for years advocated by Lord Meath, a Southern unionist peer devoted to good causes. Meath was eager that all the communities under the British flag, ‘free, enlightened, loyal’, should nourish ‘a sane patriotism’, self-sacrificing, concerned with social reform and free from any taint of jingoism. His efforts were crowned with success when the government announced in the Lords on 5 April 1916 its recognition of Empire Day.55

Southern unionists were exhilarated by the imperial ideal and inspired by the history of imperial expansion, which, it could be said, had begun in Ireland. The study of Irish history, to which they made a substantial contribution, reinforced their political convictions. Needless to say, their version of Irish history differed markedly from the nationalist picture of the Irish past. Nationalists dwelt with pride on Ireland’s heroic and golden ages, eras preceding the Norman invasion. From the arrival of the Normans, Irish history was for nationalists a long courageous struggle against conquest, confiscation and oppression. To a unionist historian Irish people had ‘a pathetic delight’ in dwelling on ‘the gloomy recollections of their abortive past’ – ‘the contemplation of their own suffering and misfortunes had a morbid attraction for them’.56 Historians with a unionist bias when surveying Irish history from the twelfth century tended to stress the constructive work and cultural achievements of the invaders and settlers, and to stress the value of the British connection. Even Bury, whose main interests, classical and Byzantine history, were far removed from Ireland, may to some extent have been influenced by his unionist background when he wrote a life of Saint Patrick. The subject attracted his attention, ‘not as an important crisis in the history of Ireland but in the first place as an appendix to the history of the Roman empire’. Saint Patrick’s great achievement, it seemed to Bury, was to sweep Ireland into the ambit of Roman imperialism. Six years after Bury published his life of Saint Patrick the first volume of Goddard Henry Orpen’s IrelandundertheNormans appeared. Anglo-Norman domination, Orpen concluded, had been distinctly beneficial to Ireland. When the Normans arrived Ireland was lagging far behind the more progressive European nations, and the ‘PaxNormannica’ had encouraged ecclesiastical reform, agricultural advance, urban growth, trade and architecture and had undermined Celtic particularism, with its primitive legal customs. When accused by a fellow medievalist of ‘not displaying more sympathy with the Gaelic element’, Orpen retorted by dwelling on the Gaels’ dynastic wars, ‘their raids of plunder and destruction’, and argued that what was termed ‘the Irish resurgence’ had tended not to Irish unity but to chaos and retrogression in the fifteenth century. ‘Well’, he added, writing in 1923, ‘they have got their great deliverance now, and all I can say is “Heaven help them”.’57

Irish history from the beginnings of the Tudor era to 1660 was surveyed by a contemporary of Orpen, Richard Bagwell, a country gentleman who was a leading member of the Irish Unionist Alliance. An assiduous worker, he aimed at marshalling the facts with a minimum of comment. His five dense volumes offer a useful introduction to a long stretch of modern Irish history and his approach, if at times colourless or flat, is certainly objective. But the thrust of his work provides the Tudor conquest and the maintenance of English authority in the seventeenth century with the justification of historical inevitability. Though Irish nationalists would have heartily agreed with his statement that the Elizabethan conquest of Ireland was cruel, they would have found it hard to stomach his explanation – that the Crown was poor, so England could not govern Ireland as she governed India, ‘by scientific administrators who tolerate all creeds and respect all prejudices’. Moreover his historical work (and his political experience) convinced him that ‘Ireland has always suffered and suffers sorely from want of firmness’.58

Lecky, an Irish landlord and an outstanding historian, was a unionist, but his HistoryofIrelandintheEighteenthCentury (1892) was marked by the qualities for which he was so widely and rightly admired: clarity, fair-mindedness and a consistent determination to comprehend and expound sympathetically the arguments of the supporters and the opponents of the union. However, in the last few pages of the work he abruptly changes gear, when he starts to discuss the unfavourable circumstances in which that ‘great experiment’, the union, had operated in the nineteenth century. The conciliatory measures that should have accompanied it had been delayed; Irish economic conditions until mid-century had been bad; the financial arrangements had seemed unfair, though recently the imperial parliament had placed ‘the unrivalled credit of the empire’ at Ireland’s disposal; agrarian agitation and conspiracy had been rife; and finally, owing to the application to Ireland of the fashionable theory of democracy, the Irish unionists, comprising ‘the great bulk of the property and the higher education of the country, the large majority of those who take any leading part in social, industrial and philanthropic enterprise’, were in three provinces virtually disfranchised. In short, nineteenth-century Irish history taught ‘the folly of conferring power where it is certain to be misused and of weakening those great pillars of social order on which all real progress ultimately depended’. Still all was not lost, there were strong forces working for the union. Belfast and the surrounding areas had progressed amazingly and in industrial development had reached ‘the full level of Great Britain’; the country in general was growing more prosperous, a multiplicity of relationships – commercial, financial and social – were drawing Great Britain and Ireland closer together, and it was clear that ‘the whole course and tendency of European politics is towards the unification and not the division of states’.

Strange as it may seem, Lecky came under fire from another Irish unionist, Dunbar Ingram, for being ‘one of the anti-English school’. Ingram, a man of considerable learning, after practising at the bar in England and India and holding a professorship in India, settled in Dublin and devoted himself to writing Irish history. An instinctive polemicist, he believed history properly deployed strengthened the unionist case. He dismissed Grattan’s parliament as ‘the most worthless and incompetent assembly that ever governed a country’. The union, he asserted, had given ‘emancipation to the Roman Catholic, a poor law to the starving, education to the needy, medical assistance to all and a land code more favourable to their industry than that of any other country in the world’. For good measure he added that every blessing the Irishman enjoyed, ‘save his religion, his bodily conformation, his soil and his climate’, was the gift of England or Great Britain.59

A generation younger than Lecky, Caesar Litton Falkiner thought that ‘the study of Irish history is a signal lesson in charity to all Irishmen’.60 A unionist parliamentary candidate in an almost hopeless constituency (South Armagh) and an energetic member of the Unionist Alliance, as an historian he was balanced, lucid and lively, with a lightness of touch and a caustic turn of phrase. His interests were wide – political history, biography, topography, and parliamentary, social and administrative history – and the steady stream of essays and articles that flowed from his pen suggest that but for his untimely death he might have been one of the most distinguished historians of his day. He was especially interested in the activities and achievements of the eighteenth-century Irish ruling world and in the development of English institutions in Ireland, including its cities and towns. Most Irish towns, he pointed out, owed their origin to the Saxon invader, and he noted the significance of the fact that ‘the succession of the viceroys is embalmed in the names of the principal streets of the Irish capital’.61 A convinced unionist, he had a melancholy awareness that ‘the descendants of the Catholic and Celtic elements’ in Ireland remained ‘inveterately opposed’ to the British connection.62 But at the opening of the twentieth century he saw that several currents in Irish life were tending to weaken antagonism to the union.63