14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

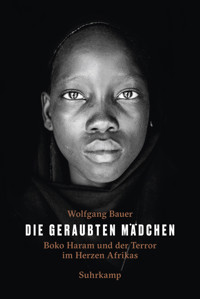

Placing himself at the mercy of Egyptian smuggler gangs in Alexandria and at sea, journalist Wolfgang Bauer went undercover to document first-hand the flight of Syrian refugees crossing the Mediterranean. The book, the first of its kind, is an incisive portrait both of the lives behind the crisis and the systemic problems that constitute it. "The last words of this book are 'Have mercy.' There is no more to say. Bauer's impressive depiction speaks for itself."—Tagesspiegel

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 158

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

First published in English by And Other Stories, 2016 High Wycombe, England – Los Angeles, USAwww.andotherstories.org

© Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin 2014

All rights reserved by and controlled through Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin.

This English edition has been updated by the author and photographer with new material.

English language translation copyright © Sarah Pybus 2016 Photography © Stanislav Krupař

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 9781908276827 eBook ISBN 9781908276834

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Editor: Stefan Tobler; Typesetting & eBook: Tetragon, London; Cover Design: Edward Bettison.

And Other Stories is supported by public funding from Arts Council England.

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut, which is funded by the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Contents

Part OneThe Beach IFarewell IFleeingThe GroupKidnappedThe Sea IThe Beach IIPrison IPart TwoFarewell IIThe WarsThe Beach IIIThe Sea IIThe OdysseyThe StormLife and DeathAlias Galauco CasimiroPrison IIOver the AlpsAlias Rani KastierElysium IElysium IIAfterword to the English EditionEpilogueAcknowledgementsPlatesPart One

The Beach I

‘Run!’ The high voice of a young man, a child still really, yells behind me. ‘Run!’ I start to run without fully understanding what’s going on; without seeing much in the dusk, we run single-file down the narrow path. I run as fast as I can, watching my feet land now on dirt and now on rock. I jump over holes in the ground, over chunks of wall, stumble and keep going. ‘You sons of bitches!’ The shout comes from one of the boys who have just driven us out of the minibuses and now run alongside us, whacking us like cattle hands driving their herds. He beats us with a stick, hitting our backs and legs. He grabs my arm, cursing as he pulls me forwards. There are fifty-nine of us – men, women and children, whole families – with rucksacks on our backs and cases in our hands, running down a long factory wall somewhere on the edge of an industrial zone in Alexandria, Egypt.

In front of me, Hussan’s back rises and falls. A bulky twenty-year-old, eyes to the ground, wheezes, soon begins to stagger, blocks my way because he can’t go on, stops suddenly, so I push him on from behind, I push with all my strength until he starts running again. Blows rain down on us. Somewhere in front of Hussan, thirteen-year-old Bissan cries with fear. As she runs, she clings to the rucksack containing her diabetes medication. ‘Scum!’ shouts the man driving us forwards. Behind me, fifty-year-old Amar wears the highly visible, signal-blue Gore-Tex jacket he bought specially for this day; his daughter thought the colour was stylish. He too gets slower and slower; his knee hurts, his back too, but as he said earlier, he’s going to make it. He has to make it. Like almost everyone here, he comes from Syria. For him, Egypt is just one stop on his journey. Then the wall turns sharply to the left and suddenly, not even fifty metres away, we see what we have been anticipating and fearing for days. The sea. Glistening before us in the last of the evening light.

In April 2014, photographer Stanislav Krupař and I joined a group of Syrian refugees trying to get across the sea from Egypt to Italy. We put ourselves in the hands of people smugglers who have no idea that we are journalists. That’s why we get herded forward with sticks like the rest; we all need to move quickly so our large group doesn’t attract attention. They would never take journalists along for fear of being betrayed to the security services. This is the most dangerous aspect of our journey: being unmasked by the smugglers. Only Amar and his family know who we really are. He is an old friend from my time reporting on the Syrian civil war. It was desperation that drove him here; he dreams of living in Germany. He will translate and interpret for us along the way. We have grown long beards and adopted new identities. For this journey, we are English teachers Varj and Servat, two refugees from a republic in the Caucasus.

We are now part of the great exodus. In 2014, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 207,000 people fled across the Mediterranean to Europe, most of them starting from Libya. In the whole year before that, it was only 60,000. They come from war-ravaged countries such as Syria and Somalia, from dictatorships like Eritrea, or in search of a life under better economic conditions.

The political order of the Middle East is collapsing. Decades of subjugation have built up immense social tensions that are now erupting into violence. Dictatorships are falling, as are the democratically elected governments that followed them. Cairo’s streets are filled with bloody demonstrations. Yemen is descending into chaos, Iraq too. Libya has splintered into regions where the militia fight amongst themselves. But no country has experienced such utter destruction as Syria, on a scale not seen since the Vietnam War and Chechnya. Cities are lunar landscapes. Many villages are all but abandoned. For three years now, Bashar al-Assad has been waging a war of annihilation with every weapon at his disposal, including chemical agents. Alawites fight Sunnis, and no one side can gain the upper hand. And to add to it all, religious extremists preaching a creed of hatred have carved out a space for themselves in this chaos.

Syria’s horrors can no longer be grasped in statistics. The UN stopped counting the dead in early 2014.

Attempts to escape the danger are also becoming increasingly perilous. Every year, 1,500 people drown as they flee to Italy and Greece. This figure is probably much higher, but the corpses are never found. Smugglers are choosing ever riskier routes as the continent improves measures to seal its borders. 400,000 police officers stand guard. Europe has built six-metre-high fences such as those in the Spanish exclaves of Melilla and Ceuta. Bulgaria and Greece have also erected structures to protect against refugees. Europe has installed elaborate radar and camera systems in the Strait of Gibraltar. The Atlantic Ocean is also being monitored between the Canaries and West Africa. Police forces, soldiers and elite units from various nations have become embroiled in the defensive battle. Helicopters, drones and a fleet of warships are being deployed. With this many troops and so much equipment, you might think they were fighting a military invasion.

And so, once again, Europe’s borders become death strips.

Over five decades, 125 refugees were killed at the Berlin Wall in the GDR, for which the free world denounced it as a symbol of inhumanity. By the time of our trip in early 2014, almost 20,000 refugees have lost their lives at the walls with which Europe surrounded itself after the Cold War. Most of them have drowned in the Mediterranean. No sea border in the world has claimed so many lives.

Europe’s birthplace, the Mediterranean has now become the setting of its greatest failure.

No other journalists have dared take a boat from Egypt, and we are aware of the dangers. We each carry a satellite phone to notify the Italian coastguard in an emergency. We decided against setting out from Libya or Tunisia. Although both are closer to Italy, the boats used there are extremely rickety. Egyptian smugglers have to cover a larger distance, so they use better ships. At least that was our hope.We were naive. We thought the sea would be the greatest hazard. In fact, it was just one of many.

Farewell I

One week before we are beaten with sticks and herded to the shore, Amar Obaid (not his real name) stands indecisively in his Cairo apartment.* It is Tuesday 8 April, his last day with his family. His seventeen-year-old daughter Reynala sits on the edge of her parents’ bed and looks at her father. ‘What should I take with me?’ he asks, standing before the open wardrobe with his hands on his hips. He can’t take much. Amar has heard that the people smugglers accept only hand luggage, no heavy suitcases. ‘Warm underwear to protect against the wind out at sea,’ says his daughter. ‘A good shirt,’ says Amar. ‘I don’t want to look like a crook in Italy.’ ‘You will anyway,’ she says, ‘you’ll grow a long grey beard.’ ‘The life jacket,’ he says, stripping it from its packaging and deliberately putting it on the wrong way round. His daughter laughs and he laughs, does a little twirl for her. Their shared laughter echoes through the apartment.

A 280-square-metre living room in the baroque style, with magnificent gold-printed wallpaper and sprawling sofas. Originally from Homs in Syria, this well-to-do family has been part of the merchant and landowner class for generations. But after the revolution broke out in 2011, Amar, his wife and their three daughters fled to Egypt. Like many of his clan, he had previously joined the resistance against Assad. To stay would have been to risk both his life and the lives of his family. He took his savings and set up a small import business in Cairo, bringing in furniture from Bali and India. He opened a shop, which employed up to eight people at its height, and travelled a lot. But then Egypt plunged into first a revolution and then a counter-revolution, as the military overthrew the democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi. In just a few months, public opinion turned against the Syrian refugees. The junta imposed visa requirements and Amar was no longer able to leave the country for business trips. He was afraid of being denied an entry visa.

Xenophobia starts to spread along the Nile. TV presenters preach hatred of Syrians, who struggle to find work. Egyptians urge others to stop buying from Syrian retailers such as Amar. Many Egyptians regard Syrians as destabilising terrorists, as freeloaders who take their jobs.

Egypt has turned out to be a trap for the fleeing family. They cannot return to Syria and have no future here.

After long discussion, the family decides to flee again. To Germany. There is no legal way to do it. They decide that Amar will go first. As soon as he has been granted asylum, he will fetch the rest of the family. At least that’s what they have planned here, in their living room, amongst the sofa cushions. It is an optimistic plan, but not impossible. They know that, despite the dangers, most boats make it across. And once he reaches Sicily, there is actually a good chance of getting to Germany undiscovered. Amar’s hope is that, like many Syrians before him, he will in all probability be recognised as an asylum seeker. The only thing standing between his family and a better future is the sea.

‘How long will the boat take?’ asks his wife Rolanda. ‘I don’t know exactly,’ Amar replies on their last evening. He might be on the boat for five days; it might be three weeks. He has heard so many different stories about the crossing.

Rolanda stays up late smoking an e-cigarette. Amar’s wife wears skin-tight black latex trousers. Gradually, his family gather around him. His youngest child, just five years old, snuggles into the crook of her mother’s arm as she eats. She instinctively avoids her father, turns away from him. She is hurt that he is leaving, even if she cannot comprehend the dangers his journey will hold. The second-youngest, a thirteen-year-old with braces, her voice rough from a cold, doesn’t want to leave Cairo. She is the only one who wants to stay in Egypt. Her friends are here, her favourite cafés – she has nothing in Germany. In contrast, the eldest girl declares ‘Heaven – Germany!’ on her Facebook page. She wants to study psychology in Germany. She begged her father to take her with him, but he said no because she is not yet eighteen. ‘She takes after me the most,’ says Amar. Both girls attend an international school whose fees take up half the family’s budget.

His mother-in-law and her servant appear at the table, the setting for their last evening meal together. The grande dame of the family, who also fled from Homs, drinks her tea with her little finger extended. She says crossing the sea is too demeaning, too risky. He is jeopardising the entire family’s future. ‘What will happen to my daughter, your wife, if you come to a watery end?’ she asks. Throughout the evening, his mother-in-law struggles to retain her composure. The servant prepares the food in the kitchen and helps Amar’s wife; she doesn’t agree with it either. She has tears in her eyes. Their cousin is at the table too; he’s a diamond merchant from Homs who will soon be leaving Egypt – for Homs. ‘I have nothing to fear from the Syrian government. I’ve been trying to get a trading licence in Egypt for half a year now, without success.’ He wants to try his luck again in Syria, where the diamond trade is booming. They are the perfect investment during a civil war: tiny stones of enormous value that are easy to conceal.

The family eats together one last time; the women have spent a long time in the kitchen. The men make a valiant effort to tell jokes, but most of the time they sit at the table with their heads bowed.

‘So who bought the shop?’ their cousin asks. ‘My accountant,’ says Amar. ‘For a quarter of its true price. He’s promised to keep on both of my employees.’ ‘I hope you’ve made the right decision,’ his cousin says. Amar looks down at the table.

He has spent today paying and calling in the last of his invoices. The family has enough money saved to survive for half a year without him.

Amar spends the last hours of his old life in fitful sleep. He must cast aside everything he once was: a father, a businessman who solved problems over the phone. He will spend the next few months as a refugee, nothing more. It’s as though his life has been reset.

The next morning, as they say goodbye at the door, Rolanda hugs him, cries and pulls him to her. ‘Oh God,’ she says. ‘I miss you already.’ He breaks away from her quickly, almost roughly, so that he doesn’t change his mind. He hurries through the door without looking back. He promised himself he wouldn’t cry. He wants to show his family that he has his destiny under control. Everything will be OK, he tells himself over and over, I have a plan. His eldest daughter follows him to the car, carrying his rucksack. He hugs her briefly and gives her a smile. My strong, beautiful daughter. She cries, although she had also resolved not to. He slams the door and pulls out of the parking space, his hands shaking.

At best, it will be months before Amar sees his wife and children again. But it could be years. And if worst comes to worst: never.

* Unless referring to public figures, the names of those involved have been changed. Biographical details have also been altered slightly.

Fleeing

In Egypt, people smuggling has a structure not dissimilar to the tourism industry. Sales points with ‘agents’ are spread throughout the country. These agents assure their customers that they work with only the best smugglers, when in reality they have contracts with just a few. The crossing costs around three thousand dollars. Cheaper and more expensive services are available, but ultimately all travel classes end up in the same boat. The agent receives a commission of about three hundred dollars. This is kept by a middleman until the passenger’s safe arrival in Italy. The sales agents – well, most of them – care about their reputation. Their livelihood depends on recommendations from the people they have successfully helped across the water.

Amar’s agent is called Nuri. An old acquaintance, muscular with a deep, raw voice, he also works in furniture imports. We share the same sense of humour, says Amar, who finds it comforting. This journey may be fraught with uncertainties, but Amar knows how to make Nuri laugh. Nuri laughs a lot. This raucous laugh, which bellows from Amar’s smartphone, will accompany us from now on.

The motorway, Amar’s route to a better future, is congested. We barely move; all five lanes are bumper to bumper, typical Cairo traffic. Amar curses, thumps the steering wheel, beeps the horn. He phones to tell Nuri we’ll be late to the meeting point, a Kentucky Fried Chicken in 6th of October City, an industrial town thirty kilometres from downtown Cairo. ‘I should have taken my sedative,’ Amar grumbles. He has two types of pill with him – Seroxat, 20 milligrams, for depression and panic attacks, and Xanax, 0.25 milligrams, for anxiety. He has been suffering from a range of anxieties for a year now. The war in Syria and the crisis in Egypt have left their mark on Amar. Fear of bacteria, fear of radiation, fear of large crowds. Finally he reaches the meeting point. A young man, Nuri’s colleague, squats in front of the fast-food outlet, smoking, his head bent over his smartphone. He has a ponytail and goatee; he nods and says that the driver will be here soon to take us to the coastal city of Alexandria, from where most refugee boats set sail for Italy.

‘How are you?’ Rolanda asks on the phone. ‘Everything’s fine,’ he says. ‘Did you pack your warm jacket?’ she asks.

The man with the ponytail puffs on his cigarette and chuckles. We wait for hours. Amar tries to wheedle some details about the journey out of him, but the man gives nothing away. Three more passengers gather by the KFC: two brothers from Damascus, Alaa and Hussan, as we discover later, and their friend Bashar. They have brand-new sports rucksacks and black woolly hats. They are wary, and sit a little apart from us in a neighbouring café. It is getting dark by the time the minibus finally arrives, and we hurriedly load our rucksacks and cases. The driver doesn’t say a word; he doesn’t greet us and barely moves his head. Elias, a waiter from Hama with short hair and a glazed expression, is already sitting in the bus. The bus drives off and turns onto the main street. ‘Shit,’ barks the driver, suddenly breaking his silence.

‘Only seven! Where are the others?’