Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

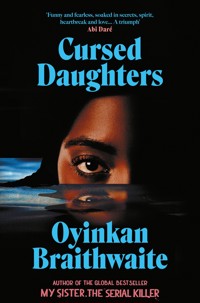

CURSES ARE LIKE HEARTS. SOME ARE MORE EASILY BROKEN THAN OTHERS... 'A worthy successor to My Sister, the Serial Killer... Pacey storytelling, nuanced characterisation and sharp dialogue... An immersive page-turner' Sunday Times -- 'A haunting, twisty tale of curses and romance' Ayòbámi Adébáyò 'A sweeping love story... I lost myself within its gorgeous pages' Jennie Godfrey 'Funny and fearless, soaked in secrets, spirit, heartbreak, and love... Impossible to put down' Abi Daré No man will call your house his home. And if they try, they will not have peace... So goes the family curse, handed down from generation to generation, ruining families and breaking hearts as it goes. And now it's calm, rational Eniiyi's turn - who, due to her uncanny resemblance to her dead aunt, Monife, and her family's insistence that she must be a reincarnation, has long been used to some strange familial beliefs. Still, when she falls in love with the handsome boy she saves from drowning, she can no longer run from her family's history. Is she destined to live out the habitual story of love and heartbreak, or can she escape the family curse and the mysterious fate that befell her aunt? -- Readers are falling hard for Cursed Daughters... 'Everyone's going to fall in love with this book' 'A stunning read. Possibly my book of the year so far' 'One of the best endings of a book I've read in a long time. So satisfying' 'Sharp, brilliantly written...and broke my heart on more than one occasion' 'I cannot express how much I adored this book - like truly, madly, deeply adored it'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 418

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Oyinkan Braithwaite

My Sister, the Serial Killer

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2025 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Oyinkan Braithwaite, 2025

The moral right of Oyinkan Braithwaite to be identified as the owner and author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. Th e names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 9781805463351

Trade paperback ISBN: 9781805463368

EBook ISBN: 9781805463375

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Product safety EU representative: Authorised Rep Compliance Ltd., Ground Floor, 71 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin, D02 P593, Ireland. www.arccompliance.com

To Temidayo Odunlami and Eriifeoluwa Odunlami

If you knew how much I love you both, you would be scared …

Falodun Family Tree

Prologue

She was a mermaid – queen of song and sea, goddess of the gill-bearing vertebrates, mistress of the hearts of men.

Only she quickly realised that in these waters, the one creature that could flourish was Mami Wata; and Mami Wata was as far from the fabled mermaid as a creature could be. There was no shimmering fin, no haunting singing voice, no glossy skin – instead a mouth crowded with dagger teeth, hands that were deformed and decaying, features that were hard to look at but impossible to turn away from. Monife had had little interest in Mami Wata, but in the end, when they found her body, she would be likened to the eerie creature.

The water was cold. And terrifying in the darkness. She was alone because Elegushi beach was not a place you went to at night. In the blackness, the beach had a completely different atmosphere; without the DJ blasting music or kids kicking up sand, it was joyless. Even in the daytime, most Lagosians stayed well away from the water; they were always surprised and a little awed when Monife wandered into the frothy waves in some skimpy bikini with her arms held wide open and her braids flying wildly behind her. Strangers would call her back, afraid for her safety, afraid to be witness to some tragedy they imagined was about to take place. But she had always, always returned to shore.

The tragedy was here, now, with her wading into the cold, thrashing waters. No. The tragedy had already happened, and this was simply the inevitable consequence. She thought of her mother, but the thought did not soften her resolve. She had left a brief note – she hadn’t had the words. Besides, they would know why; and if they were unsure, her cousin could enlighten them.

She was doing her very best to think of anything but Golden Boy. She didn’t want her last thoughts to be of him. She had already surrendered herself to him in her life; she didn’t want to surrender to him at the end also. But she was neck-deep now and she hoped his heart would shatter into a million glittering, self-pitying pieces. He would swallow his pain whole, and perhaps he would choke on it.

It was impossible to tell where her tears fell as the waves washed her clean. She was being swept further and further away from the shore, from her home, from her life. She was terrified, but she reminded herself that the worst had already happened, she only had to give in.

Part I

Ebun (2000)

I

‘Gone too soon,’ the pastor had said, and she thought it the understatement of the century. Gone too fucking soon.

The weather was all wrong. It was rainy season; at least it was supposed to be. She would have welcomed dark clouds, thunder, a perfect storm. Instead, the sun was relentlessly bright and the sky was crystal clear. She fanned herself with her hand; it did nothing to relieve her discomfort. Off in the distance, she could hear the beat of a gángan, the trumpets and the joyous chorus that accompanied it – the soundtrack was all wrong, too.

Someone grabbed her hand and a small moraine of soil was poured on to Ebun’s palm. She stared at it, momentarily forgetting what she was supposed to do … oh yes – sprinkle it on the pine prison that housed the body of her cousin. She released soil over the coffin and watched it scatter. Beside her, her mother wailed.

It was done. It was done. And Tolu was already walking away. She watched him step on grave and grass as if there were no difference between them. He had barely spoken to her mother and herself, and when he did, it was ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘okay’. Her mother had ascribed the behaviour to grief, but Ebun knew it was condemnation.

The drums were getting louder, the singing more frenzied. She was starting to believe the gbin gbin gbe of the gángan was taking place within the walls of her skull, but then a gathering of people paraded by, led by musicians. They were straight-backed, dressed in Ankara aso ebi, chatting, some even laughing and skipping over graves as they exited Ikoyi Cemetery; oblivious to the wretchedness a stone’s throw from them. Whoever it was the jubilating group had buried had likely reached their twilight years, probably had children and grandchildren and possibly died in their sleep. Not so Monife. She was, is … was only twenty-five.

Ebun looked around and saw Mo’s mourners were beginning to melt away. They mumbled goodbye to one another; some exchanged hugs. Mo’s father was soaking in the sympathy and accepting condolences as if they were his due. She stayed out of his way, lest she speak her mind. Tolu had had a similar idea – throughout his sister’s funeral, he’d stayed ten feet away from his father at all times.

She was tired and her feet hurt, so she left the cemetery as quickly as her distended belly would allow. When she got to the car, she realised the keys were with her mother. She was forced to wait under a sun that was dry-eyed and unfeeling, the sweat running down her forehead, into her eyes, down her neck and her chest. She wiped it with her hand, but it kept on coming. Her discomfort must have been shared by the baby, because the kicks came hard and fast. She was worried she would faint, so she carefully sat on the ground, under the shade of a palm tree.

How quickly life changed. The note, searching for Mo, receiving word that a body had been found, burying her … it had all transpired in the course of ten days; but it had felt like a millennium. She waited for the tears to come, as she had done since she got the news of Mo’s death, if only to relieve her of the lump in her throat and chest; but there truly was no peace for the wicked.

‘Ebun. Ebun.’ She looked up. Her mother was standing over her, eyes raw from crying. ‘Are you okay?’

What a question. She struggled to rise from the ground, so her mother helped her up. They got into the Beetle. She hoped they would drive in silence, but her mother wanted to talk.

‘It was a nice service, wasn’t it?’

‘Mmm.’

‘I think Monife would have felt loved.’

Love was what had gotten Monife buried six feet under. But Ebun chose to keep her true thoughts to herself.

‘Yes, she would have,’ she replied.

II

Her mother dropped the car keys into a glass bowl on the console table in the hallway, among the kobo coins, lint and someone’s bangles. The keys clinked against the glass and the ensuing echo tricked her into thinking that the house was empty. But alas, she soon made out the gentle murmuring of women talking quietly, as if intent on not waking any ghosts.

She could guess why they were here – Aunty Bunmi hadn’t attended the funeral because it was considered taboo for a mother to bury her child; and since it would have been unwise to leave a grieving mother alone, a few family members must stay with her. Ebun understood all that, but she couldn’t bear the thought of seeing any more people, so she began to head for the stairs. ‘Ebun,’ her mother said. ‘You have to go and greet your aunt.’

She was about to make an excuse, when she noticed something was off. On the wall to the right of the console she was looking at five framed photographs, where there used to be eight. The missing photos had all featured Mo – Mo holding her university certificate, Mo beaming at the camera with the shadow of the beach in the background, Mo with one arm around Ebun’s shoulders and the other around Tolu, pulling them tightly to her.

She took a couple of steps back and scanned the wall on the left side of the console table. It was missing the picture of Mo, Tolu and their mother awkwardly posed, and the picture with Mo in her role as bridesmaid.

‘What’s happened to Mo’s pictures?’ she asked, as calmly as she could.

Her mother looked up at the wall and sighed, scratching her forehead with a long nail.

‘I … If this is what your aunt needs, maybe it’s for the best …’

Ebun could tell her mother had not been a part of the picture-removing committee, but Kemi’s words only fuelled her anger.

‘Ebun, where are you going?’

Ebun hurried through the dismal corridor to the east wing. The way was narrow and dim, not unlike walking through a tunnel. A little creativity – lowering the walls around the courtyard that divided the Falodun home into two wings, or adding windows – would have made the house a little less claustrophobic; but then again, the iroko tree at the centre of the courtyard would probably have blocked out all possibility of natural light. She opened the east living room door to meet a collection of photographs so large that they rose almost to the ceiling, with the oldest of them devoid of colour. Some dated back all the way to the matriarch – Feranmi Falodun. She searched for her cousin, but here too all trace of Monife was gone. Ebun felt a buzzing in her head. It was bad enough that Aunty Bunmi had not been there to lay her daughter to rest, but now they were pretending Mo had never existed in the first place.

She wanted to scream. She did not know what had possessed her aunt, nor did she care. She would march up to her and demand that—

‘Ebun.’ Her mother was in the doorway, blocking her exit. ‘Ebun. Today is not the day.’

Kemi was small, only five foot – the height of a child. And considering the fact that she was always on some diet, she was probably the weight of a child. It wouldn’t be hard to shove her out of the way.

‘Mummy, please. Move.’

‘Ebun.’

‘I just want to talk to her.’ A part of her was fizzing at the thought of being angry at someone other than herself, being able, just for a moment, to release the tightness in her chest.

‘Please,’ her mother said, but Ebun pushed past her and headed for the west wing. She took the shortcut, through the courtyard, past Sango. He was camouflaged by the shadows; all but the creepy eyes that followed her. She ignored him and entered the west wing corridor. Behind her, she could hear the hurried steps of her mother’s heels against the terrazzo floors.

‘Ebun. Ní sùúrù.’

She ignored her mother’s appeal for calm.

‘Aunty Bunmi!’ she shouted as she approached the west living room. ‘Aunty Bunmi!’

The door opened as she reached it, and Aunty Bunmi stood in its frame. She was dressed in a plain skirt and blouse, not unlike her headmistress garb. Her eyes were swollen and her lips trembled. She was flanked by Grand-Aunty Sayo, Grand-Aunty Ronke, Mama G and Mama G’s obscenely large breasts. Of course Mama G would be there, whispering fictions into Aunty Bunmi’s ear. Ebun dragged her eyes from the mamalawo, choosing to focus her attention on Mo’s mother. She should have curtsied for the older women before her, and she hoped they noticed she had not observed the custom.

‘Where are her pictures?’ Her voice was low, slow and deep.

‘Ebun,’ her mother pleaded, ‘this is not the time.’

‘Where are they?’ she asked again.

The corridor was narrow; Ebun was blocking the only real exit out of the west living room. The four women were essentially trapped and withering under her gaze.

Aunty Bunmi lowered her eyes. She would not give Ebun the fight she needed.

‘It is best this way,’ began Mama G. ‘Or her spirit might linger.’

So it was Mama G’s idea? She could kill her. She had no idea why her aunt thought it appropriate to have a mamalawo here at this time, but if the woman could not hold her peace, Ebun would happily bury her on the family grounds. At the very least, she would make her regret meddling in their business. And then she would find Mo’s pictures.

Ebun took three steps, aiming to close the gap between herself and the women before her, when she felt a gushing release from between her legs. She looked down at the puddle of water, bright against the floor. ‘Shit,’ she said, and then burst into tears.

‘Ebun, ṣé kò sí?’

‘I …’ But she couldn’t get the words out. She tried to breathe but couldn’t stop crying. If she could have gathered the water pooling at her feet and shoved it back up into her vagina, she would have done; because it was early yet, her baby wasn’t due for another five weeks. But her grief and her fury must have stirred the water in her womb, and now the baby was pressing against the wall that was meant to keep her safe. It was too early.

She would lose her child; and on the day she had buried her cousin. Call it fate. Call it karma. She squeezed her eyes shut. She couldn’t follow that train of thought. Her mother was shouting.

‘What?! What?! What is it? What has happened?’ asked Grand-Aunty Sayo. They were still far enough away that they hadn’t seen. Ebun placed a palm on the wall and tried to calm herself.

‘She has wet herself,’ her mother confidently informed them. Ebun tried to regulate her breathing. Her baby would be okay. She had to be.

‘She can’t have wet herself, Kemi.’

‘Are you not seeing what I am seeing?’

‘It is her water. Her water has broken.’

Aunty Bunmi’s words were firm. She touched Ebun’s arm with a cool hand, steadying her, then she pulled her into the living room, leading her to an armchair. Five sets of eyes peered at her.

‘It can’t be her water. It’s not time yet!’ her mother shouted. No, it wasn’t time yet. Perhaps Ebun was about to learn what it felt like to lose a child.

Her aunt’s sombre eyes met her own for a brief moment. Then they both looked away. Ebun thought about the anger she had felt mere moments ago. What had she really thought she could say to the woman? All she felt now was a wave of tiredness. She spotted Sango’s dark shape disappear behind the couch.

The women were debating what to do. Grand-Aunty Ronke suggested she should lie down, close her legs and the baby would relax. Her mother was pacing back and forth, speaking in tongues, and Ebun instinctively looked around to locate one of her cousins so they could share an eye-roll; and then she remembered – Mo was gone and Tolu wanted nothing to do with her.

‘Maybe Mama G can …’ began Aunty Bunmi.

Ebun shook herself. She had no intention of giving herself over to a mamalawo and the spirits she entertained. This was her child and she would fight for her soul.

‘Just get me to a hospital.’

III

They told her to push. Push.

As if it was easy; as if they weren’t asking her to surrender herself to death.

She heard someone give a guttural cry, and then realised that she was the someone. She had been right to fear this pain. She didn’t think she would survive the experience. A voice told her she was doing well, but it was as though she were submerged underwater and the voice was trying to reach her from the surface. The words had no meaning. She breathed. She pushed. She felt the head crowning. She screamed, and it was over.

They lowered the baby into her arms, naked and crying. She stared at the child that she had nurtured for seven months – the cause of her acid reflux, the endless blood-thinning injections, the sickness, the absent-mindedness. Here she was, her daughter, in the smallest and most fragile of packages. Her skin pillowy soft against Ebun’s own. The crying subsided. They took their breaths together. Her daughter’s eyelids flickered open, and the eyes were boundless and familiar. Ebun was engulfed in a joy that was so concentrated it felt like grief. Nothing would ever matter as much as this child.

‘Beautiful hair,’ a nurse exclaimed as Ebun ran her fingers tenderly over her baby’s scalp. The statement was true enough. Her daughter’s hair was already thick and coily; likely to become long and resilient, soaking up moisture and defying gravity.

And then the moment was over. They whisked the baby away, to check that her organs were fully developed and she would be able to survive on her own.

When her daughter was returned to her, Ebun saw that her eyes were heavy with sleep. Eyes that reminded her of Monife – wide-set and downturned. She gave in to her own desire for rest. This was a moment steeped in all that was good. She didn’t have to think of anything else.

IV

The ward was dark, but she could sense that there was someone in the cubicle with her. It was Ebun’s second night in the hospital, and she had been moved to a room divided into two by a fragile curtain – leaving her with a space just wide enough to accommodate a bed, cot and solitary chair. She opened her eyes and waited for them to adjust.

She could make out a figure approaching the cot where her baby slept. At first she assumed it was her mother. But her mother was short, with wide hips, and this woman was tall and slender. Besides, her mother had gone home to sleep. A nurse? But surely a nurse would say something.

She felt panic blooming in her chest. The figure was moving towards her child with what she could only imagine were bad intentions. What else would explain this creeping about? She wanted to shout, but she was still groggy, weighed down by the various drugs keeping her from feeling pain. Her body would not do the thing she most wanted it to do, which was get up and protect her baby. She tried again to call out.

‘Nurse. Nurse.’ But the words were just a croak. Her throat was dry. Perhaps the other new mother would hear her, but no one responded to her cry.

Her heart rate quickened as the figure neared the cot. She could begin to make out that the woman was wearing an oversized shirt, revealing long legs, bare feet, a thin link chain glinting on the right ankle. Suddenly she recognised the thick hair and the bowed legs. It was Mo. Mo was here, not in Ikoyi Cemetery, in a wooden box covered by soil, but here in the cubicle with Ebun and the baby; bending over the crib, lifting the baby and peering at her face.

‘Mo. Please. Please,’ Ebun begged, even though she couldn’t have said what it was she was asking. She used her hand to hold on to the bed rail, and pushed herself up. Then she swung her feet to the floor and tried to stand. She immediately crumpled, hitting the ground hard, so she began to crawl, dragging herself to the cot.

If Mo was aware of Ebun, she chose not to show it. She was cradling the baby and rocking her gently. Neither of them made a sound. As Ebun inched closer, she noticed that Monife was wet, the T-shirt clinging to her body, her hair heavy and glossy over her shoulder. ‘Please,’ she tried to say again. Mo lifted her head slowly, and a single drop of water rolled from her hairline and fell, catching the dim light, landing with a small splash on the baby’s forehead—

Ebun woke up in her bed with a start, her heart hammering. She looked around frantically; the ward was dark and silent. She found she could lift herself from the hospital bed and shuffle to the cot, where her baby slept peacefully. And Mo was still buried six feet deep, fifteen miles away. It was only a dream. The wall between the living and the dead was impermeable; she had no reason to be afraid. It was only as she turned away from the cot that Ebun realised her foot was wet; she was standing in a small pool of water.

V

There was the time before Monife, and the time after.

The time before was slow, dreary, but most of all, it had been so very lonely. Ebun had lived in the Falodun house with her mother, who would disappear for hours at a time in search of husband number four or selling imported jewellery to the wives at various upscale Lagos clubs, leaving her eleven-year-old daughter with a list of chores to complete and not much else. Ebun had been a thin, melancholic child, who would diligently follow the instructions she was given, then wait for her flamboyant, laughing mother to come home and regale her with her adventures. She had no friends, as she found the art of making friends laborious. And she didn’t have the creativity to entertain herself. Those hours waiting for her mother to return were spent in a state of inertia; she wouldn’t have been able to say what she had done with the time.

But all that changed the day Kemi’s sister arrived on their doorstep with her two children and eight suitcases in tow. Ebun watched from between the banisters of the east staircase as the sullen sixteen-year-old Tolu and the winsome fifteen-year-old Monife dragged their baggage into the Falodun home. She watched as her mum and aunt embraced, but she refused to move from her eyrie.

‘Ebun,’ her mum called up to her. ‘Come down now. Do you remember your cousins? Come and say hi.’

Of course she remembered them. They were the cousins that lived in England. They had crisp accents and a weird aversion to the heat. They had visited two years ago, and had been unable to hide their contempt for her home and for Nigeria. But here they were again. She had gleaned from her mother’s loud phone conversations that Aunty Bunmi’s husband had a new family and his old family had nowhere to go.

‘Ebun, don’t make me say it again.’

Ebun stood up, hesitated, one foot ready to step down, but instead she turned and ran off to her room. She could only hope that when she reappeared, they would be gone. She was accustomed to these ad hoc visitors at their home – her half-brothers, who made it clear her presence was unwelcome; her father, who showed up to fulfil all righteousness; and the odd suitor for Kemi, asking Ebun awkward questions about school. Ebun slid behind doors, huddled under chairs and beds, and waited until whoever was visiting had left.

But this time, when she came out of her hiding place, her cousins were still there. And they were there the day after, and the day after that.

The trauma of being abandoned by their father was plain to see in Tolu’s behaviour. He was curt and dismissive. He would lock himself in his room and only make an appearance for food.

But Mo, Mo was different. Mo was a candle in the perpetual gloom that had been Ebun’s existence, with her made-up games, and her penchant for rolling her eyes theatrically at Ebun whenever their mothers did something embarrassing – which was often. Then there was the way she would listen to Ebun with her head cupped between her hands, staring into Ebun’s eyes. For years, Ebun did her best to imitate Mo – her gravelly voice, her large cursive writing, the music she listened to and her effortless dancing. If Monife noticed her efforts, she chose not to say anything. Except ‘I always wanted a little sister.’

Monife had been the catalyst for Ebun’s heart to start beating again, so she hadn’t been prepared for the bursts of sadness that would hit Mo and plunge the whole household into a state of crisis. There was no way to predict when it would occur. Mo would become plagued with insomnia, she would stop eating, she would stay in bed and pull the duvet over her head, saying little and doing even less. Whatever unfathomable place she had gone to, Ebun would gladly have followed, but she was left on the outside.

And then as quickly as it had begun, it would be over. She would emerge from her bedroom as brightly as before, and she would love on Ebun, pull her into hugs, take her on outings, burst into the bathroom to gossip, ignoring Ebun’s attempt to hide her body as she grew hair between her legs and her breasts began to swell. It was Mo who provided her with a sanitary pad when she noted stains on Ebun’s knickers. It was Mo who stressed that their charcoal skin was a thing of beauty.

And it was Mo who told her about the family curse.

Falodun Family Curse

The Beginning

Feranmi Falodun (the one who was cursed) was rumoured to be an especially beautiful woman. Her skin was smooth, soaking up the light; her hair was thick, long and heavy. Her laughter was said to sound like a babbling brook. Her fingers were long and delicate, and she was good with them too, crafting baskets, plaiting hair, knitting clothing. By the time she was ten, her purse was heavy with the kobos she had earned from her talents.

Her father had high hopes that she would fetch a good bride price, so she was the only one of his daughters he bothered to educate. And as he had predicted, she attracted many suitors. But the man who caught her eye in the end was practically a stranger. He had come to her village to bury his father. She spotted him as he walked around the village, observed him as he flirted with the mothers and grandmothers, and scrutinised him as he played host to the crowd there to witness him lay his father to rest. He was new and interesting – a learned man who lived in the city and wore English suits. But he paid her no mind. At first.

She didn’t like being ignored, and so she crept into his father’s bungalow one night, past the room where his mother loudly snored and into his arms; a seductive spirit who (as he would tell his wife years later) overwhelmed him, body, mind and soul. The night they spent together was a fever dream. When he stumbled into the light in the morning, he wasn’t entirely sure that anything had taken place. The spirit had already gone. He didn’t even know its name.

He had planned to leave that day; his father rested six feet under and his things were packed. His driver brought the car to the front of the bungalow, and he readied himself for the long journey home. There was a large group of people, led by the chief, marching his way, and he was briefly curious where they were going. They stopped just short of him, so he greeted them warmly, remembering to prostrate for the chief. But the chief’s response was much cooler than he was accustomed to.

‘So you were planning to eat plantain and leave without paying?’ the chief said in his proud English. The man chose to respond in Yoruba.

‘Nígbà wo ni mo jẹ dòdò, tí mi ò ṣ’ọ́wọ́?’

The crowd split in half, revealing the seductive spirit that he had spent the better part of the night trying to tame. Feranmi. Her name was Feranmi, and she was the answer to the question he had asked. The saliva turned solid in his throat. It would not be so easy to leave town.

They came to an agreement. The man from the city provided goats, yam, fish, palm oil, orogbo, sugar and honey. He also provided cash. It was the bride price that Feranmi’s father had always envisioned. Then, under an auspicious sky the following week, the man sat resplendent in his expensive agbada, and they brought the girl he had acquired to kneel for him in her matching colours. He purchased a modest but well-built home to situate her in. He consummated the marriage, which was the easiest part of the whole affair; and then he was free to leave.

He barely thought of Feranmi between his brief, infrequent visits. His life was not particularly changed by her introduction to it. It was five years before his first wife insisted on accompanying him to see the house he had built in the village – a home she assumed would be her children’s inheritance. On the long journey, the man’s driver observed his employer sweating profusely, and asked if they should turn back. But his oga could barely speak. When they arrived at the village, the driver was discreetly sent ahead to ask Feranmi to pretend she was in his oga’s employment; but Feranmi had no interest in playing housemaid, or in hiding Wemimo, her precocious daughter. She met her husband’s wife with her head held high, her eyes bright and unblinking.

The husband they shared suddenly remembered that he needed to greet the chief. He left the two women to sort themselves out. Forty-five minutes later, in response to their high-pitched screams, a crowd gathered. They were found locked in combat, with torn clothing and blood trickling from various deep scratches. It took five minutes to pull them apart, and the growing audience watched as the first wife rose to her full height, pointed a trembling finger at the second wife and declared:

‘It will not be well with you. No man will call your house home. And if they try, they will not have peace. Your daughters are cursed – they will pursue men, but the men will be like water in their palms. Your granddaughters will love in vain. Your great-granddaughters will labour for acknowledgement, but they will fall short of other women. Your daughters, your daughters’ daughters and all the women to come will suffer for man’s sake. Kò ní dá fún ẹ́.’ Then she swiped the blood from one of her many wounds and smeared it on the ground.

Feranmi laughed. She was confident in herself, in her beauty and in the beauty of her daughter. But this time when her husband left the village, he did not return.

Twelve-year-old Ebun told sixteen-year-old Monife that she didn’t believe in curses.

‘That’s fine,’ said Monife, between the slow chewing of gum, ‘but what if the curse believes in you?’

VI

The morning after Ebun dreamt of Monife, her mother returned to the hospital with her sister in tow. Had she come alone, perhaps Ebun would have shared the dream, and the sense of foreboding she had. But the sisters came together and so she said nothing of her fear.

‘Ẹkú ewu ọmọ,’ said Aunty Bunmi, congratulating Ebun on her survival, because childbirth was serious business, like going to sea and being unsure if you would ever see land again. She received the congratulations gracefully. She wondered how Aunty Bunmi was processing everything that was unfolding. She had lost a daughter, and her niece had gained one. She couldn’t imagine what would be going through her aunt’s head.

‘Are you sure you don’t want to contact the baby’s father?’ Kemi began.

‘Mum …’

‘If he is refusing to take responsibility, we can talk to his family.’

‘Why would you assume he is refusing to …’

She lost the thread of what she had been saying as she watched her aunt making her way over to the cot. She heard the gasp. A part of her realised she was anticipating it.

‘Kemi. Ah ah. Mo mọ̀ ohun tí mo ń rí. She is the spitting image of—’

‘Yes,’ Ebun cut in. ‘Yes. I guess … I guess she looks a bit like Mo.’ There was no point denying it. The baby’s eyes, her long, narrow nose, the wide forehead. It was as though she had given birth to her cousin’s child.

She had begun to notice the resemblance as she held her baby, watching her snuffle around her breast, then latch. She noted the similarities as she changed the first nappy, careful not to touch the tender leftover from the umbilical cord. And when the nurses came in, marvelling at her baby’s thick, generous hair, she was quick to stress that the attribute could be traced to their progenitor, Feranmi.

‘A bit? A bit ké?’ Aunty Bunmi leant into the crib and eagerly lifted the newborn out of it. ‘Monife has come back to me. She has come again.’ Ebun felt as though someone was pouring freezing-cold water down her spine.

‘What?’ she said as she struggled to sit up. Her mother saw her distress and stood quickly from the plastic seat beside the bed, approaching her sister and holding out her arms for the baby. Aunty Bunmi’s grip only tightened.

‘Maybe you should give her to me, Bunmi,’ Kemi said gently.

‘Look at her eyes. These are Monife’s eyes na.’

‘Bunmi.’ Her mother’s voice had taken on a deeper undertone, but her aunt would not be distracted; she rocked the baby, still searching for signs proving her daughter had returned.

‘And her forehead. See how long her forehead is.’

‘We all have the forehead, Aunty,’ added Ebun from the bed. ‘It is not Monife’s forehead alone.’

Aunt Bunmi sighed. ‘My daughter has come back to me.’

‘She has not,’ Ebun said, her voice becoming high-pitched and shaky. ‘See, she has a birthmark Mo did not have. On the back of her neck.’

Her mother crept closer as Aunty Bunmi turned the newborn over; she would see what Ebun had noticed whilst dressing her in a onesie – a trail of pale skin, like droplets on a glass. They were small and easy to miss on the fresh-from-the-womb skin, but she could tell they were there to stay and she was reassured by the knowledge that Monife had had no such mark.

But if she had thought Bunmi would be discouraged by this, she was swiftly disappointed.

‘It is like someone has pressed three fingers into her skin. This mark, she was set aside. Don’t you see? She was wrenched back from the jaws of death. She was—’

‘She is not Monife. Monife is gone.’ Ebun felt an ache at the back of her skull. She would have given anything to see Mo. She had loved Mo. She still couldn’t believe she would have to go on through life without her. But her child would not be the vessel her cousin could use to come back into this life. You were given one life and Mo had decided what to do with hers.

‘Ebun,’ hissed her mother.

‘What?!’

‘Mind yourself,’ she whispered, jerking her head at Aunty Bunmi, whose eyes were rapidly filling with tears.

‘This is my daughter, Mummy.’

‘Nobody is saying she is not.’

‘She is our daughter,’ said Aunty Bunmi firmly. ‘And we will love her even better this time.’

VII

On the plate was the head of an agama lizard in all its glory. She picked up the fork beside it, poked at the meat and then dropped the utensil.

‘I think I’ll pass.’

‘You cannot pass,’ Aunty Bunmi informed her ‘You are a mother now. You must learn to sacrifice for the sake of your child.’

‘By eating a lizard?’

‘By denying yourself.’

She thought she heard Mo scoff, but Mo wasn’t there to scoff. Only a week in and already being made to feel as if she wasn’t ‘mother’ enough. Even now, Aunty Bunmi cradled the baby in her arms. Ebun had to engage in a tug-of-war just to hold her own daughter. The only time Aunty Bunmi readily released the newborn was when Ebun had to breastfeed. Even worse, Sango hovered, unwilling to be more than ten feet from the baby.

‘It is a small thing,’ her aunt continued.

‘We all had to do it,’ added her mother gently.

This tradition had been sprung on her as she readied herself for the arrival of the pastor. It was day nine, so already a day late for having her child prayed for, blessed and named.

She had wanted a simple ceremony, with herself and the baby in attendance, her mother and aunt; and Tolu, who was yet to respond to her invitation. He had moved out of the Falodun house a day after his sister’s funeral, a day after the birth of Ebun’s child, and he wasn’t taking her calls. So the ceremony would be even smaller than she had planned. Surprisingly, her mother readily agreed to having a more intimate event. Ebun assumed it was because a single mother with a mystery baby daddy was more scandal than even Kemi was willing to bear, but she should have known better than to trust the easy acceptance of her terms; two hours before the pastor was due to appear, they sprung this ritual on her.

‘I am not interested in fetish practices.’

‘That is the problem with you young people, you think you know everything. This isn’t fetish, it is our culture. Our tradition.’

‘What she is saying is the truth, Ebun,’ added her mum. But if she was so confident that devouring a lizard was above board, why the hurry to get Ebun to consume the creature before the pastor arrived?

Ebun stared at the lizard. She was still adjusting to the sleepless nights and the sore nipples; she didn’t have the energy to fight anybody. She picked up the fork and knife laid on either side of the plate. The lizard’s head was covered in scales; its eyes stared sightlessly at her. At least the creature was cooked. She took as small a forkful as she could, and gulped it down quickly. For a moment she thought it was going to come back up, but she grabbed her glass of water and gulped the liquid, calming herself and her stomach.

There was a shared sigh from the two older women.

‘Ehen! Now we can move on.’ Her mother gestured to the wooden coffee table, where various ceremonial condiments had been laid on a glass tray. This part of the ceremony, at least, Ebun was familiar with. She hadn’t been to many naming ceremonies, but she understood that this was a far more typical practice than eating lizard. Her mum beamed as she passed the items to Ebun and Bunmi, stating the name of each thing and its purpose as they took a bite or a sip.

‘Oyín: so that the life of our child will be sweet and happy; obì: to repel evil.’

‘No evil will come near her,’ added Aunty Bunmi. They collectively ate the honey and the kola nut.

‘Àtàrẹ̀: so that she will be as fruitful as the plentiful seeds.’

‘Yes o!’ Aunty Bunmi wiped tears away with her free hand, and Ebun pretended not to see. Instead she directed her eyes to the sleeping baby, in her too-big satin dress.

‘Òmí: so she will never be thirsty and no enemies will slow her growth.’

‘Her enemies will not even see her.’ And together they drank.

‘Èpò: for a smooth and easy life.’

Ebun found herself sucked in by the rhythm and meaning of the words her mother was speaking. She would later blame the hormones, but she wanted all these things for her daughter. The palm oil tasted thick and harsh on her tongue.

‘Ìyọ̀: because her life will not be ordinary. And òrògbó: so our child will live a looooong life. Amen!’

Amen! Ebun repeated to herself.

And then it was time for the actual selection of the names. Her aunt produced an empty bowl, then immediately dropped a fifty-naira note into it, symbolically buying her right to provide a name for the child. Ebun held her breath. If Aunty Bunmi dared to suggest the name Monife, Ebun would reject it. Could she reject it? She would find out then.

‘What will you name our daughter?’ asked Kemi.

‘Motitunde!’ I have come again. Monife would have been the less offensive choice. Aunty Bunmi was basically branding the baby a reincarnation. Yes, Ebun’s child looked like her cousin, but babies changed; this would not be her daughter’s final form. Ebun opened her mouth to speak, but her mother dropped money into the bowl, thus sealing the name.

‘I have a name!’ Kemi announced.

‘What is it?’

‘Abidemi!’ A female child born in the absence of her father. They were trying to torment her. Her mother passed her the bowl.

It was Ebun’s turn now. She paid her dues and told them the name she had chosen for her daughter.

She would be better and greater than the ones who had come before her.

She would be a woman of integrity.

Ebun named her:

‘Eniiyi.’

Part II

Monife (1994)

I

Monife returned to find her home clouded in fog. The incense was so thick she could barely see. She considered walking back out, returning to the university grounds and burying her head in her books. Nothing good would come of going deeper into the Falodun property, where delusion was surely waiting for her. For a couple of minutes she stood in the hallway and pretended she had a choice – go back to school or enter the house; go back to school or cross the threshold; go back to school or engage with crazy.

But in truth, she avoided staying on campus for longer than she had to. Growing up in London, she had taken for granted that she would pursue the arts in England; but fate and a philandering father had meant her life had not gone quite as she had planned. Instead she was reading law in Lagos, with no real intention of becoming a lawyer, under the tutelage of uninspiring old men, commuting from the home her great-grandfather had built.

Great-Grandpa Kunle had claimed he didn’t believe in the curse, but still he had planned for it. There were exactly six rooms in the two-storey home, one for each of his daughters – Toke, Bimpe, Afoke, Fikayo, Sayo, Ronke – so that whatever happened to them, they would have somewhere to escape to. And at various points, they had all needed somewhere to escape to.

The Falodun home was virtually a museum; no one here ever thought to throw things away, except perhaps her cousin. Ebun found the clutter oppressive, but Mo was charmed by the hair claw that may or may not have belonged to Grandma Afoke, the pearl earrings that purportedly belonged to Grand-Aunty Toke and the dusty bible owned by Grand-Aunty Bimpe – her name was inscribed on the first page.

The house was interesting and eccentric, with its creaky floors, flickering lights and doors that swung open of their own will at night. But this, the cloying smell of incense, made her eyes water and her heart sink.

She walked past the main living room, where she heard the faint roar of the crowd on the wrestling channel – so Aunty Kemi was in and pretending that all was well; fantastic. She marched towards the west wing of the house, where the fog was foggiest and the scent at its strongest. As she drew nearer, she could make out chanting. She arrived at her mother’s door and knocked. The chanting didn’t stop; apparently her mother had no intention of welcoming her in. She opened the door.

The room was dim – the lights were off, curtains drawn – all the better to welcome in some nefarious spirit. She managed to avoid tripping over the stool that belonged tucked in below the dressing table. As the fog cleared and her eyes adjusted, she saw that there was a void in the centre of the room, where her mother stood. Furniture had been pushed out of the way to make space for whatever shenanigans were taking place.

‘Mummy,’ she said. But no other words followed. Her eyes took in her mother’s body. Her breasts and stomach were beginning to sag, but her arms and thighs were toned, and the hair that Monife had inherited, though greying, was clearly still a force to be reckoned with. She wore it in her signature six cornrows. Mo noted the keloid on her mother’s arm, the skin tag on her neck and the beauty spot on her stomach. She could note all these things because her mother stood before her naked, but for the wrapper that was loosely tied around her waist.

The world saw a woman who was unflappable, a woman of God, a respected headmistress at the local school – but behind closed doors, her mother flirted with strange spirits and gods.

‘Mummy.’

Her mother did not respond, so Mo strode over to the stereo, where the chanting was coming from, and pressed the stop button. Then she opened the curtains and a window. She took another look at her mother.

The older woman had a glazed look on her face; the whites of her eyes were tinted red. Mo could only imagine what substance she had ingested, and from where. Her mother squinted at the light, shielding her eyes with her palm.

‘Close it. Close it,’ she muttered as she waved her other hand at Mo. ‘You will disturb them.’

Monife looked around her. She could not tell whether there were spirits in the room with them, but what she could see was a pot with a strange-looking plant creeping out of it, a small bowl of herbs from which smoke was rising and some misshapen stones scattered about.

‘What are you doing?’ she asked, even though of course she knew. This was perhaps her mother’s seventy-fourth attempt to lead her exhusband back to them – despite the fact that he had a new wife and two children under five, shacked up in what used to be their London home. He had moved on. Mo and Tolu had moved on. But still, her mother used any free moment she had to try to pull off in the spirit world what she hadn’t been able to achieve in the physical.

‘This,’ Bunmi announced, pointing vigorously at the bowl of herbs, ‘will clear his eye. He will remember who his family is.’

Mo sighed. The fog was beginning to dissipate. ‘It’s been four years, Mummy. He is not coming back.’

‘We can undo the things that could not previously be undone.’

‘Who are you quoting this time?’

‘I am not your mate, Monife. You will show me respect.’ But her words lacked any real bite; she sounded drunk.

‘You need to stop giving these people your hard-earned money.’

‘This time it will work. He will come back to me.’

‘We don’t want him to come back.’ Though even as she said it, Mo felt the familiar pang. He was her father; she had loved him for fifteen years, and then he’d discarded her as if she were nothing. He rarely called. Sometimes she wondered if she had done something to offend him. Still, she would never voice that hurt. She would swallow it down so deep that she’d forget it was there. And she needed her mother to follow suit.

‘No! This isn’t your father’s fault. It is the curse.’

The curse. The curse. Damn the curse.

‘How much did you spend?’

‘Kí ló sọ?’

She was confident her mother had heard the question, but she repeated herself. ‘How much did you spend? On these stones? And whatever has made you high?’

‘What are you talking about? I was given a spiritual herb …’

‘Is that what they are calling weed now?’

‘Weed?’