8,34 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

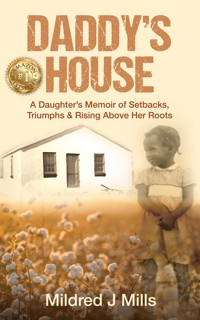

In this poignant memoir, a determined young girl becomes a formidable woman, confronting obstacles with courage, determination, and spirituality.

The third of seventeen children born to strict Southern Baptist parents, Mildred is so capable, at seven years old, her father taxes her to keep the books for his 60-acre farm. Mildred leaves for technical school in Ohio, and at 19, her world is turned upside down. On her way home from work, a stranger kidnaps and sex-traffics her for an evening to a baseball team. Mildred buries the memory of that night beyond consciousness and abandons her budding singing career, first love, and new job to start over in a different city.

Abuse for Mildred didn’t begin on that fateful 1970 day in Columbus, Ohio. She’s raised by a soft-spoken, loving, abused mother and a disciplinarian father, prone to emotional and physical abuse. Daddy’s House: A Daughter’s Memoir of Setbacks, Triumphs & Rising above Her Roots chronicles Mildred's life from an Alabama farm saddled with a 225-pound per day cotton quota to executive positions in corporate America. In the cotton field, her reward is Daddy’s leather strap if she fails to deliver.

After fleeing the rape, Mildred completes a year at university but finds herself pregnant, unmarried, and a college dropout dependent on a welfare check—but not for long. Throughout this gripping story, armed with an unbreakable mother-daughter bond and her father’s work ethic, Mildred confronts obstacles with stubborn resilience. At the end of the journey, Mildred does what God put her on earth to do—help others. And in so doing, she is able to recapture that buried memory and heal. Spending precious days comforting her father on his deathbed, Mildred finds peace and the strength to forgive every offender, including her daddy, a man she deeply loves, who is also the man who hurt her most.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 408

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Published by

Hybrid Global Publishing

333 E 14th Street

#3C

New York, NY 10003

Copyright © 2024 by Mildred J. Mills

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law.

Manufactured in the United States of America, or in the United Kingdom when distributed elsewhere.

Mills, Mildred J.

Daddy’s House

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-961757-27-1

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-961757-29-5

eBook: 978-1-961757-28-8

LCCN: 2023922577

Cover design by: Julia Kuris

Copyediting by: Nicole Frail

Interior design by: Suba Murugan

Author photo by: Lelund Durond Thompson

This book is a memoir. The events are portrayed to the best of the Author’s recollection of experiences over time. While all the stories in this book are true, some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of the people involved.

www.mildredjmills.com

DEDICATION

In loving memory of Mama and Daddy, whose stories live on in these pages.

I dedicate this book to my parents, Abraham and Mildred Billups, who loved the younger me enough to set me free to realize my dreams. You instilled discipline, structure, kindness, respect, and an unparalleled work ethic, which shaped me into the woman I am today. It took years for me to realize that you gave me the best you had. I am grateful for your gifts.

I can be changed by what happens to me.But I refuse to be reduced by it.

—Maya Angelou

If people are doubting how far you can go,go so far that you can’t hear them anymore.

—Michele Ruiz

Acknowledgements

Writing this book has been a long, arduous journey, and I am fortunate to have many friends and family who supported me across the finish line. From the bottom of my heart, thank you for your encouraging words, phone calls, and inspiration. You were the wind at my back on the steepest climb up the mountain.

My dearest husband, Darryl, your keen eye for catching minor missing details that enhanced my story was invaluable. Thank you for loving and believing in me and being my anchor on every leg of this journey. To my son, Richard, your gentle nudges kept me writing through my darkest days when I wanted to quit; thank you. I thank my daughters—Ashaki and Nadria, grandchildren, and every brother and sister who encouraged me or helped me remember.

To my editor, Nicole Frail, you pushed me to dig deeper, let down my guard, and freely tell my truth rather than shield those I wished to protect. For those reasons, I have a richer story.

Dr. David Hicks: I will never forget your tenderness as my advisor, guiding me through and beyond Wilkes University’s Maslow Family Writing Program. How can I ever repay that kindness?

To my mentor, Beverly Donofrio, I sincerely appreciate you taking me under your wing, befriending me, teaching me the true meaning of shaping a story, and guiding me to “The End.” You made me see the good in every character, even when I tried not to.

Karen Strauss and the incredible team at Hybrid Global Publishing: thank you for your passion and patience in becoming a partner in making my dream of becoming “Author of” come true.

Lelund Durond Thompson and team, how do you turn a photograph into a work of art? Thank you for capturing my best self through the camera lens and providing stunning images for the cover design artist to work with.

Thanks to every educator—especially Dr. Elizabeth Harper-Neeld and Ashley Sardoni—who ignited a writing spark in me, beginning with Mama and Daddy. I apologize upfront for forgetting anyone and will be offering thanks for years to come; I offer special thanks to a small group who regularly checked on me, some sending me gifts and flowers: Willie Blake, Joseph Bates Abbie Brothers, Syni Champion, Dr. Richard & Dianne Cohen, Sedare Coradin, Betty Neal-Crutcher, Yvonne Danielly, Theodore (Ted) Gates, Valerie Golden, Doyle Gorman, Marilyn Hayes, Johnnie Horn, Cassandra Johnson, Janice Johnson, Carmelle Killick, Karen Kristie, Renee Logans, Dr. Ayanna Kersey-McMullen, Ellen McTigue, Gwen Lusk, Dolores Mitchell, Dee Pipes, Squeesta Collier-Semien, Cynthia Smith, and Cherise Story. My Sharon Lester tennis team, you girls rock on the courts and in my corner. Kristin Andree and The Renew Team, thank you for enthusiastically checking on me regularly. My Wilkes University cohort and biggest cheering squad, I won’t forget how much we’ve been through together. The women of WIVLA, thank you for warmly embracing me.

Lastly, thank you, God, for giving me the strength to heal, the willingness to forgive, and the courage to tell my truth.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1:A Mother’s Dowry

Chapter 2:Honor Above Resentment

Chapter 3:A Girl in Training

Chapter 4:Thunder and Lightning

Chapter 5:Sex, Life, and Death on the Farm

Chapter 6:Body Changes

Chapter 7:A Stubborn Streak

Chapter 8:Up, Up, and Away

Chapter 9:Crossing State Lines

Chapter 10:The Purple Heart

Chapter 11:Harsh Realities

Chapter 12:Starting Over

Chapter 13:Immaculate Conception

Chapter 14:The Unemployment Office

Chapter 15:Frigidaire Corporation

Chapter 16:Matrimony

Chapter 17:On My Own

Chapter 18:A Painful Separation

Chapter 19:My Son

Chapter 20:New Love and Turmoil

Chapter 21:Marriage and Separation

Chapter 22:Stinging Words

Chapter 23:Hard Drinkin’ Lincoln

Chapter 24:Retaliation and Deposition

Chapter 25:Women and Children

Chapter 26:Secrets Revealed

Chapter 27:A Memory Returns

Chapter 28:Precious Lord, Take My Hand

Chapter 29:A Return to Daddy’s House

CHAPTER 1

A Mother’s Dowry

One starlit morning when I was eighteen, a lump like a fist clamped my heart as I rushed out the back door and down the steps with my blue Sears Roebuck suitcase containing everything I owned. I grabbed the door handle of the pink Super 88, where Daddy sat behind the wheel, beckoning me to get in. A chorus of bullfrogs sang harmoniously with the humming engine, and the car’s headlights beamed a path across the cow pasture, drawing me forward.

I turned and gazed back at Mama, a silhouette in black plastered against the white cinderblock wall. She stood on the concrete porch, her too-thin pink-and-blue floral shift waving like a flag in the gentle breeze. Tears, illuminated by the reflection of headlamps, gleamed against her cheeks as she watched her namesake walk away, the first of her children to do so. It was June 1969.

I was the third of Abraham and Mildred Billups’s seventeen children, born in Wetumpka, Alabama—a small, dusty community in the sticks of Elmore County. Our white cinderblock house sat at the dead end of a red dirt road that ran straight through the woods at the butt end of the earth. I stood there torn between the two people who gave me life: Daddy at the steering wheel and Mama on the porch. When I looked from one to the other at two o’clock that morning, it was abundantly clear I wanted freedom from them both. Yet, I couldn’t help but wonder if I was doing the right thing.

I glanced over my shoulder and waved a last goodbye to Mama. She threw open her arms and reached for me. A strong breeze whipped open her flimsy duster and exposed her large breasts, protruding stomach, and big thighs shaped like cured hams. In pitch blackness, this startling sight was like something out of a comedy, but nobody laughed. I asked myself: Is it wrong of me to leave her?

I wondered what life would be like waking up mornings not guided by those hands, rough and steady, or encouraged by her gentle voice. I was too young then to grasp the magnitude of the dowry Mama had already given me. She didn’t have a penny to offer but had bestowed on me a sense of worth, pride, and independence as much a part of me as my skin color.

I ignored Mama’s nakedness and focused on the curly ringlets above her shoulders, creamy skin the color of a banana peel just before the brown spots come, full lips, and raggedy yellow flip-flops held together by a pink safety pin. I had no idea then that she was already eight months pregnant with my youngest sister, the seventeenth and last child she would bear. I drank in her beauty under the crescent moon that hung like a front porch swing, and my heart crumbled, hearing each muffled sob that escaped her throat. But no amount of crying would keep me here with my fortress, my friend—my strength.

I raced back up the steps, and Mama folded me into her arms like egg whites into a cake batter. I absorbed her warm, firm body, felt her heartbeat, pressed my face against her cheek, and tasted salty tears. Mama squeezed and held me like she feared I might disappear. “Mildred, I knowed from the day you was born you would be my first child to grow up and leave me,” she said in a soft-voiced wail that tore at my heart.

But I was past feeling guilty about finding my place in life. Hell, yes. I was leaving my Mama.

I looked behind her at the sagging screen door and whispered, “Mama, I can’t stay. I need to make a better life for you and me.”

I will never forget the resignation on Mama’s face as she wiped the tears from her eyes, faced me with her hands on my shoulders, and repeated a passage I’d heard her recite many times: “Trust in the Lawd wit’ all your heart and lean not on your own understanding. In all your ways, acknowledge Him, and He will direct your path.” She chuckled nervously. “I ain’ never told you this, but that’s my favorite scripture. Proverbs.”

Daddy laid on the car horn, and Mama and I winced.

“Do the best you can with what you have, and remember, Mildred, nothing beats a failure but a try. I done packed everything a girl needs in your suitcase.” I nodded but didn’t speak. With that teaching, Mama gave me her blessing and released her young daughter into the night, covered by God’s grace and mercy.

I walked away from Mama wrapped in love, the remembrance of her raggedy-toothed smile emblazoned on my heart. I slipped onto the bench seat across from Daddy and waved through the passenger side window until the car backed away from the house, and I could no longer see her standing on the porch in the dark.

Tears threatened to slip down my face as I thought how, only yesterday, I had sat alone on that same little porch, perched like a cat with a fresh bowl of milk. I remember thinking then that it had been two months since my eighteenth birthday, six weeks since Daddy last beat me, a week since high school graduation, and the first time since I was five that I was not in the cotton field on a weekday. I felt twelve feet tall on that June day, lighter than a feather.

On that porch, I’d been ecstatic, knowing that in less than twenty-four hours, I would wave goodbye to the cotton fields of Wetumpka, Alabama, when Daddy drove me to a technical college in Columbus, Ohio. I had locked my fingers behind my head, closed my eyes, and leaned against the concrete wall of the only home I’d ever known. Then, I said to the rising sun, “Kiss. My. Face.” Shivers of excitement pinched my nipples as sparrows soared and bumblebees buzzed—unrestricted. Soon, I’d be free from the sights, sounds, and smells of Mama, Daddy, and my fifteen surviving brothers and sisters.

With so many people always buzzing around, I’d thought my home was a place of confusion; I couldn’t decide whether to love its beauty or hate its stench. Every time I stepped outside the house onto the little porch, the smell of chicken shit, hog pens, and the maggoty red outhouse spread its arms like a greeting committee. Yet, beyond the pigpen, where the soil was rich and black, the sweet smell of honeysuckles and cultivated fields eased into my bloodstream.

As Daddy backed away from the little porch, just outside the door where my sisters slept, I wanted to soak in every part of the cinderblock house and the family I left behind. I envisioned my seven younger brothers sleeping on one narrow bed or the floor of the screened-in back porch, then glanced through the car’s rear window as we passed the front porch, where, as a child, I had delighted in the joy of playing jacks with my older sister, Bunny. The house faded to black amid crackling pea gravel under Daddy’s racing tires. I faced the road ahead and thought, So many porches, only two bedrooms.

Burrowed into the corner of the Oldsmobile passenger seat, hoping Daddy wouldn’t notice me, I gripped my purse so tight my knuckles were white. I should have been shouting hallelujah and jumping for joy that I had graduated high school and was off to a bright future. But I knew I was never more than one wrong word and a U-turn away from being back in the cotton field. So, there I sat, strung tight enough to have a nervous breakdown, trying not to set off the lunatic in the driver’s seat.

Daddy flew down country roads, gripping the steering wheel like a lover as we headed toward I-65 North, leaving a trail of red dust in the dark. I closed my eyes, inhaled deeply, and filled my lungs with country smells from the open car windows—fresh-mowed grass, honeysuckle blossoms, pine needles, and skunk. The farther north I rode in Daddy’s car, leaving everything and everybody familiar, the more I wondered what aromas would greet me in the unfamiliar territory of Ohio.

With that thought, I was suddenly afraid. I realized that in my haste to be free of my parents, I hadn’t thought of what a sheltered existence I had lived in my two-parent home where, despite struggles, they remained together to raise their family. I remembered a story Mama told me when, as a young girl, I asked her how she and Daddy had met and ended up on the farm.

My parents grew up two miles apart and knew each other from church and school. Mama was the youngest of ten, Daddy the youngest of twelve, and both were the first high school graduates in their families. Mama and Daddy married in 1946, a year after he returned from Egypt. He was twenty-five; she was twenty.

In October 1950, after purchasing a sixty-acre farm with Daddy’s GI Bill money, they left his mother’s house on a horse-drawn wagon, carrying all their worldly goods and my two older siblings: four-year-old Brother and seven-month-old Bunny. Mama was already pregnant with me.

I imagine Daddy at the reins calculating how long clearing the land and building a farm would take, facts that come naturally to a brick mason and carpenter. I envision Mama thinking about me, embracing me, protecting me, the three-month-old pod growing inside her belly. She told me how happy she had been to have a place of her own but how terrified she was of being miles away from her mom (ten miles), moving to an isolated, wild, and untamed place.

Recently, sitting across the dining room table from Mama, I asked how she adjusted to the unfamiliar surroundings and overcame her fear. Mama clasped her hands and smiled. “Eventually, I grew to love the peace and quiet and watching things grow.” Remembering her words, I was swaddled in a cloak of peace and calm, heading to a faraway place with an opportunity for my own growth. I faced the road ahead. A kernel of hope and satisfaction sprouted inside me with every mile, remembering what I was leaving behind. I knew I had taken my last ass whipping from Daddy. And I decided right there in that car that if Daddy couldn’t break me, I would not be broken. I also remembered that I had left a praying Mama behind, one who had breathed prayers into my spirit as she held me to her bosom only minutes earlier.

CHAPTER 2

Honor Above Resentment

I grew up believing—as I still do—that Mama had a direct line to God; she called on Him often and with such fervor that I knew He would grant her wishes. Almost every time I walked through our home and found her seated, her eyes were closed in prayer.

Mama prayed about everything. She even prayed before whipping me. I recall the creased face, quivering lips, and sad pleas as Mama lectured me after I committed a punishable offense. This time, I’d hurled a fork at Brother. I had cooked dinner and was setting the table, and he shoved me. I was ten; he was fourteen. I cocked back my right arm like Sandy Koufax and hurled a fork that sailed past his head and through a windowpane, shattering the glass. Mama huffed into the dining room from outdoors in time to witness the whole thing.

“Git out there and bring me a switch,” she yelled. “You and your hot-headed temper.” I handed her the switch. “Lawd, have mercy, Mildred, this gonna hurt me more than is’ gonna hurt you.” I stood eye-level with Mama as she sat on the edge of a ladder-back chair, making this declaration. In my young mind, I thought she was nuts. Why pray for God’s mercy, whip me anyway, and claim it caused her pain?

I didn’t want to add to Mama’s agony, so I lowered my head and tried to look repentant, although I wanted to punch something rather than get hit. By the time she was mad enough to whip me, I had deserved it.

“I’m gonna let you slide this time,” Mama sometimes said, only to come back weeks later with “I’m gonna beat you for the old and the new” and order me out of the house to pick a switch from a peach tree. I trudged along slowly, looking over my shoulder, hoping she’d get distracted by some other disaster. I even wished God would remind her through Psalm 127:3 that “Children are a gift from the Lord; they are a reward from him.” But after so many babies, she likely didn’t view them as gifts anymore.

With a peach branch in her hand, Mama became Superwoman. I skipped around, yelping like an excited puppy, while she flailed that switch through the air. It sounded like a swarm of bees, and upon contact with tender little legs, it left an impression. Mama’s whippings didn’t last long, but she raised her voice an octave during the act. “You know why I’m beatin’ your tail?” She didn’t wait for an answer, and I didn’t offer one. “I ain’t gonna let you grow up like you was hatched by the buzzards and raised by the snakes.” I still don’t know what that meant, but it sounded awful.

Some Friday nights, I was thrilled when Daddy disappeared to places unknown, even though it left Mama home alone with their house full of babies. The house was filled with laughter and lightheartedness on those nights. I felt like the little girl I was—free to dream and be anything or anybody I wanted to be, even a butterfly. Mama allowed us to express ourselves freely, not fearing Daddy’s wrath. She’d gather her children in the living room, saying, “Let’s have a prayer meeting.” She’d begin the service soft and slow with a song like “Tell Him What You Want,” a call-and-response spiritual, in her off-key voice. Mama would sing, “You know Jesus is on the main line.” We’d chime in, “Tell him what you want/tell him what you want.” I loved the call-and-response section. Mama would yell “Call him up!” three times, a sound of desperation in her shrill voice. We’d echo the call, ending with the refrain, “And tell him what you want.”

I often wondered if those prayer services occurred when Mama craved human touch to fill lonely nights. I now realize she taught us how to pray, share, and bond with each other on those Friday evenings as we clapped, laughed, and sang like we were part of the Hallelujah chorus. Mama called our names in chronological order. “Now it’s your turn. What song you wanna sing, or would you like to pray?” She never forced participation yet encouraged us, making us believe we could perform like Mahalia Jackson or James Brown.

After singing, Mama would drop to her knees in front of our old sofa—its floral cover meant to conceal bare wood frames and broken springs hidden like skeletons in a casket. She’d prop her elbows on the couch and rest her chin in her palms. We’d bow our heads, close our eyes, and clasp our hands.

Mama spoke to Jesus like He was sitting on the couch drinking the wine He made from water at the marriage at Cana. Her prayers were almost always the same: “Dear Heavenly Father, I come before you in the humblest manner I know how.” She asked Him to bless the sick and afflicted everywhere, the prison-bound and those less fortunate than us. Mama asked forgiveness for her sins by thought, word, or deed, and for things not pleasing in His sight; forgive those who had sinned against her. “Father, throw your long arms of protection around us and keep us safe from all hurt, harm, and danger.” Every request sounded more urgent than the last. She wrinkled her face and pleaded with God as if her life depended on it.

“Hallelujah,” we’d shout. “Amen.” The more we responded, the longer Mama prayed. Sometimes we’d peep from under our eyes at each other, crinkle our faces, and giggle silently. But there was no more giggling when Mama said, “Lawd, let me live long enough to raise my own little chillun so they won’t be scattered everywhere. When my work on Earth is done, please give me a resting place somewhere around your kingdom, for Christ’s sake. Amen.”

As the words to her prayer sank in, I couldn’t decide whether to cry or sneak off to bed. I’d look at my siblings, barefoot and dusty, sitting in a semicircle around Mama. We played and worked outside every day, did not own a change of clothes, and only bathed on Saturday nights. Who but Mama would want such a raggedy crew?

Sometimes, Mama spoke to us like she was going away. “I done taught y’all to take care of one another, no hittin’ and fightin’. Whatever one got, I expect you to share.” She would lower her head, shake it slowly from side to side, and sit silently for several seconds. We stared at Mama and each other with our eyes glazed over like we were destined for an orphanage. No one moved, just sat on the floor with our faces twisted up, lips quivering, and eyes unfocused. For the next few days, we were helpful children, no bickering—perfect church scholars.

Years after I left home, I asked Mama, “Why did you wake me in the middle of the night to take care of your children? Why not Bunny or Rachel?”

We sat across from each other at the twelve-foot rectangular table that Daddy and his sons wrestled down several flights of stairs at an office building to provide seating when all his children came home. Mama slowly rubbed her palms together in a handwashing motion.

“Well, Mildred, you just had a way with my babies; they responded to you.” She rocked gently on a chair and stared through the sliding glass patio door at cows grazing near the lake.

I let that sink in for a moment. “Mama, what does that even mean?”

She squirmed on her chair and looked directly into my eyes. “Well, Bernice wasn’t no good with chillun, and Rachel couldn’t stay awake.” Bunny, whose given name was Bernice and the name Mama always called her, was a year older, and Rachel—a year younger.

I resented having my sleep disturbed, but I took Exodus 20:12, “Honor thy father and mother,” seriously as a child, and I still do. I greeted each screaming baby with a sharp pinch to their little fat thigh. What the hell? They were already squalling, and I was tired and filled with resentment. Why was I called at five o’clock every morning for the last nine or ten years I lived at home to cook homemade biscuits, grits, eggs, gravy, and sausage or bacon for a house full of people?

Those last years at Daddy’s house, I would think, That is not my husband peering across the hot stove looking for a meal, and Those aren’t my hungry children with the wet diapers that I rocked back to sleep at night. Did they call me because I never complained and meticulously performed tasks like a bionic servant? Of course they did! They were no different than an abusive employer, husband, friend, or slavemaster who piled work on a willing spirit until she was ready to snap. But I would bide my time and bite my tongue, focus on one goal, get the hell out of Alabama, and make my own way.

While questioning Mama about choosing me as a caregiver, I asked if she remembered packing my suitcase when I left home at eighteen. Her eyes lit up. “Oh, yeah. I’ll never forget it,” she said. “I packed needles, thread, a thimble, and everything I thought my girl, who wasn’t never coming home again, might need. Oh, I knowed you’d always come back to see me but never again to stay.”

I was pleasantly surprised that without ever discussing it, Mama knew precisely how I felt as a child leaving home. Yet, she did not cling or insist that I stay. I asked, “How did you know I would never return?”

“I just knew. You was just a girl but looked like an old woman, tired and ready to go.” She told me she understood why I ran away from the burden they placed on me. While writing this book, I remember Mama told me, “Mildred, you was a brave and fearless girl, courageous enough to leave home,” a strength she told me she lacked.

Two days before I sat in Daddy’s car with my packed suitcase, he’d sidled up to me in the middle of a cotton field full of waist-high Johnson grass and gnarly nutgrass that I thrashed with my sharp hoe. He said, “We done come to count on you a awful lot ‘round here, Babe. I dunno whether we can afford to let you go to Ohio. Who you reckon can cook and do all the other things we trained you to do?”

I felt a tight ball in my stomach as I hoed and chopped weeds like they were Satan’s horns. I lowered my eyes and said, “I don’t know,” and wondered how that was my problem. I thought, I’m no special monkey; “train” somebody else.

“Well, me and Mama gonna talk it over tonight and see what we need to do.”

I stared at the ground and chopped even harder. “Yes, sir.” God, help them make the right decision. Please don’t make me run away.

CHAPTER 3

A Girl in Training

Every Sunday until we outgrew the car, the family piled in Daddy’s 1949 Fleetline Chevrolet, dressed in our best clothes, and headed to Sunday school at the church his grandfather had built. Daddy floored the gas and flew past any car that dared get in his way. The wind whipped through the open windows and pinned us children to the back seat. Mama clutched her church hat with one hand and the baby with the other but knew better than to open her mouth.

Pea gravel crackled, and a cloud of red dust chased us like a whirlwind when Daddy swung the Chevy into the churchyard and parked in his spot under a large oak tree. He was the adult Sunday school teacher, piano player, and head deacon. Only his oldest brother, the pastor, had more power. Daddy grabbed his King James Bible, slammed the car door, and hustled up the steep church steps to meet with the boys’ club, his older brothers, in the vestibule where a large rope hung from the church bell. Years later, Mama told me that he and his brothers held formal meetings on “how to keep a woman in her place, namely their wives.”

Mama slid off the front seat with an infant in her left arm and hoisted a toddler from the back seat onto her right hip. Eight-year-old Brother closed the car door. He, five-year-old Bunny, and I, then four years old, held hands and strolled behind Mama. A sprinkle of church ladies smiled and spoke. Mama said, “Hey,” in a voice sweet as syrup.

Years later, she told me how the church ladies giggled behind her back, seeing her and her children lined up like stairsteps across a church pew. “I heard the whispers: ‘I bet she pregnant again.’” Mama claimed it didn’t bother her, but the whine in her elevated voice contradicted that notion. “I was a married woman wit’ a husband, after all. Some of them women had chillun and ain’t had no husband.” When she was really riled up, she tsked her lips, wrung her hands, and wrinkled her brows. “Lawd, sometimes I cried and prayed and asked God how come Teetie and Sista (her older sisters) couldn’t have some a dem babies?” I thought she sounded like a woman confined to a life sentence, and I wondered if sitting in church was her escape.

Every Sunday morning, I raced up the steep steps of Mt. Zion Baptist Church, a sturdy white building with a steeple so tall it looked like a stairway to heaven. I squeezed into the same corner spot on the first row of a hard wooden pew behind a potbellied stove.

Aunt Lizzie—the children’s Sunday school teacher and Daddy’s older sister—marched into church like a bulldozer and snapped open her worn King James Bible. “Good morning, class,” she chirped and jammed one hand on a hip until each student responded. Then Aunt Lizzie delved into her favorite topic—the devil. She stomped back and forth in front of us, wearing white, old folks’ shoes, and preached hellfire and brimstone, condemning a sleepy bunch of farm kids to damnation.

One Sunday, just as my head rolled back and my eyes closed, a chilling screech split the air when the massive double doors at the back of the church swung open. Every child swiveled around like synchronized swimmers to examine the newcomer.

Wham! Aunt Lizzie cracked a twelve-inch ruler against the top of the pew. “I done told y’all to turn yourselfs ‘round and stop lookin’ back in church.” She smacked the ruler again, just as she sometimes cracked our knuckles. “Keep it up, you gonna turn into church asses, and you goin’ to hell.” Aunt Lizzie waved her King James in our faces. “Lemme remind you what the Good Book says happened to Sarah when she disobeyed God.” She slammed the Bible on the front bench and smacked her hands together. “Sarah looked back and, Whap! Just like that, she turnt to a pillar of salt.” I envisioned Sarah stuck on a salt block like the ones I saw in cow pastures, licked to death like a white lollipop at the end of a stick.

It was no accident that the young children’s class was next to a wide-mouthed wood-burning stove. Uncle Huey, Daddy’s older brother, crept to the heater and pried it open with a black fire poker. Sparks crackled and flew onto the wood floor. When the heater was so hot the outside glowed red, the stooped man who resembled Ebenezer Scrooge brushed off his powder-blue seersucker suit, pushed his eyeglasses up his nose, glanced at us, and smiled a wry grin. With every child wide-eyed and focused on him, he slipped away, his reminder of what happens to bad kids accomplished.

By the time I was in third grade and ready to advance to the next class, I had heard so much about Satan that I wanted to stand on that pew and shout, “Show me the devil!” Not a single Sunday passed that Aunt Lizzie didn’t narrow her eyes and say, “Y’all know what the devil look like?” No one responded. “He got a sharp, pointy tail, red horns, and a split tongue like a snake—got a hot pitchfork, too. He’s nuthin but a deceiver.” I couldn’t have put the words together back then, but I thought the devil sometimes sounded mean and scary, like Daddy.

At the breakfast table when I was three, and everyone’s eyes were closed for grace, one-year-old Sonny grabbed a sausage patty from Mama’s plate and stuffed it in his mouth. Daddy swatted his hand hard enough to bring a welt. The sound of his palm against the baby’s flesh was like a lightning crack across breaking glass. “Boy, keep your hands off your mama’s plate.” Sonny’s reaction was immediate, a wail that wrapped itself around your heart and left a small callus. Daddy snatched him by one arm and pummeled his backside with rapid blows that sounded like gunfire from an automatic weapon. He slammed the baby back on Mama’s lap.

Mama lowered her head and chewed sausage like it was a rubber hose, something hard to swallow. She blinked back tears and rubbed Sonny’s back like it was fragile. She tapped her foot and sang softly. “Hush, now, baby, don’t you cry.” She pinched off a piece of sausage and handed it to him. Sonny grabbed it with chubby fingers and popped it into his mouth. Tears still streaked his face, but he grinned into Mama’s eyes, revealing four baby teeth. While she sang, her half-smile didn’t hide the rot that had eaten away at her four front teeth.

That same year, when I was supposed to be asleep late one night, my bedroom door creaked open, and Mama tiptoed into the room. It was winter. The wind howled outside and whistled across the threshold beneath the back door. She pulled two sticks of firewood from behind the door, stuck them in the potbellied stove, and stoked the fire with a black poker. Mama patted the covers where her young children slept, puttered around the room, and straightened the blankets, checking if we were asleep.

The sound of rocks crunching under tires approached the back door fast and stopped too close to the little porch outside our bedroom. The car door slammed. I heard Daddy laughing and mumbling to himself. He eased open the creaky screen and crept inside.

Mama leaped from behind the door, swung the fire poker, and barely missed his head. She yelled something that sounded like, “You gonna stop that catting around, and I mean it.” Daddy snatched the fire iron from her as effortlessly as he could have taken it from three-year-old me. He knocked her backward across the foot of the bed and pressed the poker against her throat. Daddy looked like he was wrestling one of his cows when, with one hand, he yanked his arms out of his olive Army overcoat and flung the coat over Mama’s face. She screamed, kicked her legs, and tried to jump off the bed. Then, she lay silent, still as a corpse.

I sprung up in bed with my mouth frozen open, my voice in my throat. Daddy pressed the poker harder against Mama’s neck. I wore a white cotton underslip and panties and clutched a patchwork quilt Mama had made. A white-hot flash slapped me, saying, “Do something.” I hollered, “Mama, wake up.” She didn’t move. I screamed. “Daddy, you killed my Mama!”

He startled out of his blind rage. “Gal, shut your God-damn mouth and get back to sleep.” My two sisters and a baby brother, sleeping in the same room, never moved or opened their eyes. Mama’s underskirt covered her face like a white sheet over a dead body and exposed her naked bottom. That night, I wished I were big enough to gouge his eyes out with that hot poker.

The same year he almost killed Mama, I’d wandered out to the little porch, whistling and looking for Daddy. It was so hot inside that Mama’s face and arms looked like melting ice cream cones. “Gone out there wit’ ya’ Daddy and sit under that shade tree.” I jumped at the chance to get outdoors and watch him work. Those brown eyes were focused, and every move of his calloused hands deliberate, like a well-oiled machine—no wasted motion. Daddy and Brother were under the black walnut tree in the backyard, yanking on a makeshift hoist—a massive chain with links that looked like giant horseshoes looped across a pulley mounted on a tree limb. The enormous black walnut tree and a large pecan tree provided shade to cool the house, but they were no match for the Alabama heat in August.

Daddy’s khaki shirt clung to his back. His face gleamed with sweat. The muscles in Brother’s skinny arms pumped like pistons as he struggled with Daddy, hoisting the engine from the 1949 Chevy Fleetline. I plopped onto the ground under the shade tree—my homemade white dress with tiny green flowers spread out like a picnic blanket around my feet—and cracked black walnuts with half of a brick, fishing delicious meat from the hard shell, eating a few, and stacking some on my dress for Mama.

I heard a distant sound like popcorn growing louder and louder as it approached the backyard. A large black car snaked down the dirt road, crunching pea gravel as it crept behind the house and parked so close to the Chevy that even I couldn’t squeeze between the two vehicles. A white man popped out of the driver’s side of his Chrysler like a jack-in-the-box, close enough that I could have written my name on his dusty brown shoes. I dropped the brick, scooted behind the tree, and struggled to ignore his flabby belly resting on his belt. His shades were so black that my reflection stared back at me from their lenses.

The man wrinkled his face, gazed over the top of his dark glasses, and whistled low, incredulous. He stuck his fists on his hips and said, “Ugh.” He looked at the chicken house, cows grazing in the pasture, and at Maude, our horse standing in the stable swishing flies with her tail. He strolled up to Daddy. “Is you Abraham?”

Daddy stood five-foot-eight and was a solid one hundred sixty-five pounds. You didn’t want to tussle with a man who made a living as a brick mason, farmer, and carpenter, a man who worked more than sixteen hours every day running a farm. The brown eyes inside his chiseled face zeroed in on a target like laser beams. His fists looked like sledgehammers, and each finger was as big as a frankfurter, the kind they call red hots. No amount of cleaning removed the black grease from fingernails thicker than silver dollars. “Who wants to know?” he asked, barely moving his lips.

The white man walked around Daddy’s Chevy and kicked the tires. He said his name, but I don’t remember it. I’ll call him Mr. Goodrich. “I’m from B. F. Goodrich. You three months late on ya’ payments for them tires.”

Daddy leaned back, jerked the chain hard, and grunted. The engine inched a little further from the car. He still didn’t look up but spoke in a slow, measured tone. “Well, I ain’t got the money right now. Soon as I get it, I’ll be sending it on to ya’.”

Mr. Goodrich cleared his throat and stepped so close that Daddy wrinkled his nose like he smelled something foul. In a drawl only a southern white man can mimic, he said, “That ain’ good enough, Abraham. Ima collect dat’ money or dem’ tires. Which one’s it gonna be?”

One of Daddy’s strictest rules to us children was, “I better not ever hear of you starting no trouble, but if trouble comes knockin’, you better make sure it don’t never come back.” The trunk of his car stood open. There were wrenches, greasy rags, screwdrivers, and tools strewn everywhere. Daddy jerked his head up and locked eyes with Mr. Goodrich. I slipped behind the pecan tree when the muscle in his jaw clenched.

Daddy let go of that chain, and with a speed and sound loud enough to burst an eardrum, the motor slammed back under the car’s hood. Shag, our brown and white collie, snarled and obeyed Daddy’s “heel” until the car engine broke loose. Then, the dog split the air with a bark that sent chickens squawking. I hugged the tree and stared at Brother; he stood near the car, unmoving like he had seen a ghost. We both watched Daddy, whose eyes were barely visible slits. He swiped his hands across the front of his khaki shirt and left five grease prints. In three strides, he was at the back of his car. Daddy yanked a tire iron out of the trunk, slung it across his shoulder like a baseball bat, and lunged toward that white man who looked like he was running a football drill, backpedaling faster than most people ran forward.

With a voice low in his throat, Daddy said, “By God, you must can’t hear! I said ain’ got the money. Now git off my place right now, or there’s gonna be trouble.”

When Mr. Goodrich raced to the driver’s side of his car, a warm trickle rushed down my legs and onto my bare feet. Daddy stared over the top of that tire iron like a double-barreled shotgun. The hairs stood on Shag’s back as he bucked and reared like a stallion and tried to get his teeth into Mr. Goodrich, limited only by the length of his restraint.

The man dove into his car, fumbled to jam the key in the ignition, and flipped it in reverse, spinning pea gravel around the black walnut tree. Shag almost became roadkill. That man sped away like a red-faced convict on the run with his hair flying behind him. He hollered out the car window, “You better git that money to us, Abraham, or I’ll be back to pull them tires off that car.”

I was almost four years old, an age when people think kids won’t remember. After witnessing that scene, I knew if B. F. Goodrich never collected a dime for those tires, that man would not set foot on our property again. The man with the tire iron and the raging dog was enough to give me nightmares. That was the first time I thought Daddy was crazy. And yet, days later, I would be charmed by his singing or his use of family game nights, when he’d pull out dominoes, checkers, Chinese checkers, and bingo, teaching us to think strategically through problems. I fondly remember the man who showed up on those nights, clapping his hands, speaking softly, and teaching his children strategies for competing and winning.

My best memories of Daddy are of him singing. The following spring, I was four and trailing behind him as he sang “The Battle of New Orleans” or “Amazing Grace.” When he said, “We fired our guns, and the British kept a-comin’,” my little-girl ears heard, “The biddies kept a-comin’.” I didn’t know anything about the British, but I knew about our baby chicks. I was a teenager before I learned the difference.

For years after he grew older, Daddy and I laughed about the “biddies.” I asked him why he sang that song so often. He said it reminded him of the days leading up to his departure from New Orleans to fight in World War II. He loved telling the story of his long journey on a ship to Egypt. The trip lasted so long that the only food remaining was “camel hips.” He rocked gently on his swivel chair with an incredulous look. “I saw this long leg laying on a table, and I asked, what is that?” One of his shipmates told him it was dinner, a camel’s hip. “Man, I looked that leg over and decided I don’t want none of that.” Daddy told the man, “I’ll just wait ‘til we get where we going to eat my supper.” Daddy clapped his hands, reared back, and laughed each time he told the story, remembering how he devoured the camel hips after days with no food.

Daddy surprised me during one of our laughing sessions when he was ninety and I was sixty. “I really enjoyed hearing you whistle when you was a little bitty thang,” he told me with a twinkle in his eyes. I had longed to hear those words when I was a child. Sometimes, when I saw him coming from a distance, I’d burst into song or begin whistling, trying to impress him, hoping for a compliment. I had longed to be close, but I also kept my eye trained on him, fearful of his rage and wary of his trickery.

I was learning that Daddy was especially tricky about paying his debts. Like earlier that summer, in August, when the sun was barely up, but the temperature hovered well above ninety degrees. The cotton was ripe for picking. After breakfast, Daddy grabbed me by my arms and swung me above his head. I wrapped my legs around his neck, clutched his head with my little arms, and hung on for fear I would fly off his back.

Daddy tore past the two full-sized beds in the girls’ room, the smell of pee as potent as Clorox. The rounded metal headboards with little iron slats, small enough that a child’s head wouldn’t get stuck, looked more like prison bars than beds where girls slept. I felt a slight shiver as I glanced back, hoping I wouldn’t see maggots crawling in the sinkhole in the middle of the mattress again tonight like there were sometimes. Daddy pushed through the lopsided screen door. Green flies darted inside and landed on the beds, drinking from pools where too many babies slept. He loped down the steps of the porch, through the backyard.

A summer breeze bathed my face as I enjoyed a piggyback ride on my handsome daddy’s back. His smooth black skin and curly hair glistened in the sunlight. The rhythm of his work boots against the ground was like chords from black and white piano keys. Brother and Bunny ran behind us and struggled to keep up. I wondered why they looked like they were about to be hanged.

At the cotton field, Daddy spun me to the ground, and his six-foot cotton sack appeared from somewhere, and he slid its wide strap around his neck. The bag trailed behind him like a wedding gown train. He smiled and placed me on the bag like I was precious cargo. I crossed my legs at the ankle and enjoyed the cotton stalk parasol above my head, fascinated by spotted monarch butterflies that flitted and kissed cotton leaves. The white bolls were wide like the welcoming hand of God, watching over me.

Daddy bent over, snatched cotton from two rows, and stuffed it through the neck of the sack. I tumbled to the ground when the bag was nearly full, and he never noticed. I dusted myself off, scrambled back up, and hung on tighter while he hummed “Amazing Grace.” Fat mosquitoes stung my bare feet, legs, and arms until they puffed up and bled.

Bunny poked along beside Daddy and tugged cotton sprigs like they might bite, sliding them into the bag hanging from her neck like a flowered noose. She stared at her bloody cuticles and sniffled. Thick black plaits stood on her head like the arms of the cross. Her dress, a tattered brown thing, hung off one shoulder. I waved, smiled, and tried to make her feel better. She rolled her eyes and looked the other way.

Seven-year-old Brother looked like an old man laden by the six-foot sack hanging from his back. Now and then, Daddy yelled, “Come on, Boy!” Brother could work like a horse on mechanical things, but his fingers weren’t nimble at picking cotton. I peeked through the stalks and smiled. He had a pained expression on his face. What could make him so sad? I wondered.

“Boy, go up to the house and draw a bucket of cold water from the well; don’t you forget the dipper, neither,” Daddy hollered. Brother tore out of the field, happy to take a break and try to please his father. His overall strap flapped back and forth across his shoulder as he raced beyond the hog pen and scooted under the barbwire fence. Black dirt cooled my fingers while I dug holes and avoided hairy black worms.

I had been riding on his sack for three months when Daddy called Brother, Bunny, and me into a huddle. “Let’s have a little contest. Babe, I betcha you can pick more cotton than Bunny and Brother.” Looking back, I should have been suspicious when he shot me that sly grin. He pulled a buffalo-head nickel from his pocket, held it in his palm, and flashed it before the three of us. It reminded me of how magicians show you the empty hat before a trick. Daddy said, “You beat ’em both, and this nickel is yours.”