Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Folk Tales

- Sprache: Englisch

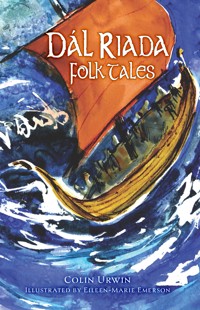

Founded fifteen centuries ago by the legendary Gaelic king Fergus Mór mac Eirc, Dál Riada was a most unusual ancient kingdom. From the Antrim Glens and Rathlin Island up through Kintyre, Argyll and the Inner Hebrides to the Isle of Skye, it was inhabited by Gaelic seafaring warriors and Viking raiders. With great skill and boundless courage, they navigated around the many islands and countless miles of treacherous coastline. They fought mighty battles, endured wild ocean storms and met with whirlpools and whales. Their presence still echoes in the old place names, and their stories of strange sea monsters, witches and otherworldly creatures have been passed down through the generations. In this collection, storyteller and folklorist Colin Urwin reimagines a few of the very best.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 281

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedicated to the memory of my father,Ray Urwin (1923–1982)

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Colin Urwin, 2025

Illustrations © Eileen-Marie Emerson, 2025

The right of Colin Urwin to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 977 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

SKYE

1. Sgáithach and Cú Chulainn

2. The Swan Maiden of Skye

3. The Sea Cattle of Skye

4. The Three Faerie Women

5. The Widow of Loch Mor

6. The Three Black Cats

7. A Rare Breed

8. The Devil’s Buttermilk

9. The Makers of Dreams

10. The Fishermen, the Woman and the Whale

11. The Wise Chieftains

12. The Child of Swan Bay

RAASAY

13. The Witches’ Revenge

EIGG

14. The Inquisitive Ghost

MUCK

15. The Death of Diarmuid

ARDNAMURCHAN

16. Luran and the Charmed Knowe

LISMORE

17. Beothail’s Bones

MULL

18. The Wise Mother

19. A Sister’s Curse

20. St Columba and the Squirrel

IONA

21. The Wisdom of St Columba

22. The Faerie Mistress of Iona

TIREE

23. The Brownie of Baugh

COLONSAY

24. McPhee and the Seal

25. The Faithful Runt

26. McPhee and Dounhulia

THE CORRYVRECKAN

27. The Whirlpool of Breacan

JURA

28. Kaelin the Wanderer

ISLAY

29. The Swan of Good Fortune

30. The Swan Maiden of Islay

31. The Faerie’s Wisdom

32. The Lady of the Emerald Isle

33. Aileen and the Hoodie Crow

34. The Three Sisters and the Corpse

CARA

35. The Cara Brownie

ARGYLL AND KINTYRE

36. Robin óg and the Faerie Pipes

37. Black McKenzie of the Pipes

38. The Chieftain, the Crane and the Cook

39. The Kintyre Fox

40. Caivala of the Glossy Hair

RATHLIN

41. The Strange Guests

42. The Sleeping Warriors

43. The White Horse – An Capall Bán

44. The Fisherman and his Wife

45. The Last Fox

NORTH ANTRIM AND THE GLENS

46. The Hireling Girl

47. A Bark from Beyond

48. The Breed of the Old Mare

49. The Farmer, the Henwife and the Hare

50. A Shirt Tale

51. A Wee Lift

52. A Viking Legacy

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Heartfelt thanks go to my wife, Carol, for her continued support during long evenings when I remove myself to read and write, or when I am away somewhere telling stories and singing songs.

I am also very grateful to the many people who support my creativity and performance career by inviting me to their events, coming along to sit in the audience or purchasing my books and recordings.

Numerous people have assisted in so many small ways to see the completion of this project, answering questions, translating Irish and Scots Gaelic, and just enquiring how I was getting on. I appreciate all your help and encouragement. Special thanks go to Dr David Hume MBE, Ulster-Scots historian, author and broadcaster, who kindly agreed to write the foreword.

I am indebted to Nicola Guy, a commissioning editor at The History Press, and all her colleagues with whom I have worked. It is always a pleasure.

Last, but by no means least, I would like to express my immense gratitude and admiration for the work of E.M. Emerson, artist and illustrator and, I’m pleased and proud to say, friend. Her beautiful art is simply stunning, and I hope readers will appreciate, as I do, the lengths to which she goes to bring an extra layer of magic to the pages of my books.

Foreword

The Belfast poet John Hewitt reflected in his work ‘Lost Argo’ on the story of a boyhood model yacht that his father bought him and brought to Islandmagee in County Antrim on their summer holidays. In the delight of having the small boat, however, the ebbing tide took it beyond his father’s reach at Brown’s Bay; opposite the stormy gap, the poet tells us, ‘she stalled, shivered and headed out, as if enthralled by the far prospect of the Scottish shores’.

The prospect of the Scottish shores similarly enthralled me, growing up on a hillside farm overlooking Islandmagee and the North Channel. On a clear day Portpatrick and the Galloway Hills were visible, the Ailsa Craig further north, and beyond that Kintyre. On a favourable day the Paps of Jura were also part of the panorama. Those Scottish shores were not such a far prospect, 12 miles across at the narrowest point between Torr Head and Kintyre, and just over 20 miles from Portpatrick to the Antrim coast.

The North Channel that divides the two landmasses was more of a communication channel in ancient times than a divide, and although much history has come and gone over centuries, the coastlines of Antrim, Argyll and western Scotland endure. It is also enthralling to me to think of the ancient people who crossed from Antrim to Argyll and eventually formed the Kingdom of Dál Riada that straddled the North Channel. As the legend of Cú Chulainn on Skye (retold in this volume) further shows us, the sea did not divide in any meaningful way.

This common land and seascape has much to offer us by way of legend and history, and Colin Urwin has assembled a remarkable collection of stories from Kintyre, Argyll, the Hebrides, Rathlin Island and the Glens of Antrim. There are stories of fairies, banshees, of the Ulster warrior Cú Chulainn, of Robert the Bruce, swans, seals, witches, the ‘Devil’s Buttermilk’ and much more. Colin has taken these stories and added his own unique imprint to them, preserving them for a new readership and future generations.

I was particularly taken by the story of ‘The Kintyre Fox’. It is remarkably similar to the story of ‘Tod’s Rodden’ on Islandmagee. Both have as their central feature a cunning fox that has learned to use a hanging branch to swing out of the path of pursuing hounds and get to its den safely. And both have a similar ending. The Islandmagee story was printed in national reading books in Ireland in the nineteenth century (I have my grandfather’s copy). Although it would be disappointing to learn that one story might just be a copy of the other, neither should we discount the truth that, just like foxes, storytellers are cunning and clever, and that the two stories might be separate entities. I hope they are.

In this volume of stories can be found common denominators which we all find enthralling; there is drama, suspense, sometimes scary goings on, little people and larger than life heroes. For most, we must suspend our natural belief. The art of the storyteller is to take us smoothly and without question to a different reality that we can believe in. Colin Urwin has produced a wonderful collection of stories. Be enthralled as you journey through the pages of his book!

Dr David Hume MBE

Ulster Scots historian, author and broadcaster

Magheramorne, County Antrim

Introduction

Long before Ireland or Scotland ever developed distinct national identities, what would become Erin and Alba were divided into many smaller kingdoms with local chieftains and kings vying for power and territory. Perhaps the most unusual of these kingdoms was Dál Riada – Dál meaning portion of and Riada referring to some long-forgotten clan name or the like (see also Dál Riata or Dalriada).

Said to have been founded in the fifth century by the legendary Gaelic king, Fergus Mór mac Eirc, at one time the territory included what is now north-east County Antrim – the Antrim Glens and along the north coast to include Rathlin Island. To the north was what is present-day Argyll, from Kintyre up through the Western Isles, or Inner Hebrides, to the Isle of Skye.

Swirling in and around this ancient kingdom and her many islands and countless miles of rugged coastline was the restless waters of the Sea of Moyle – the north channel where the Atlantic Ocean meets the Irish Sea – and what is now the Sea of the Hebrides. Far from being a barrier, the sea connected every part of the kingdom. Only one good day’s sailing separated Skye from the southern Antrim Glens, the two furthest points. The widest sea crossing was between the Antrim and Kintyre coasts, which is little over 12 miles at the closest point. A journey of this distance was easier to undertake and less perilous over water than through thickly wooded countryside full of wild boar, red stags and wolves, not to mention bands of potentially hostile clansmen.

It is suggested that the islands and hinterland of the Argyll coast were raided and later settled by a tribe of Gaels from the Irish side of the north Channel. Indeed, Argyll literally means Coast of the Gael. This tribe was known to Greek and Roman writers as the Scoti. Some historians have suggested that the Scoti were to the Gaels what the Vikings were to the Norse – seafaring warriors and pirate raiders. In any case, the Scoti subsequently gave their name to Scotia – Scotland – but that was not for several centuries to come.

Like all the smaller kingdoms that once existed throughout the islands of Ireland and Britain, their borders were in constant flux and their rulers always under threat. Dál Riada did not last as long as some others. It flourished and declined within three or four centuries, though scholars debating the exact details of its rise and fall are far from agreed. Suffice to say, it is a complex historical conundrum involving complicated genealogies and scant archaeological or documentary evidence to prove or disprove any one theory, timeline or set of events.

What is not in dispute, however, is that despite recognised federal borders being in place this long many centuries, and strong national traits and identities firmly established on either side of the Sea of Moyle, the people of what was once the kingdom of Dál Riada share a common Gaelic heritage. Ulster Irish, for example, and especially the dialect once spoken on Rathlin Island, bears closer correlation to the Scots Gaelic of the west coast than Irish spoken anywhere else on the island of Ireland. Latterly, accents and dialects of English heard throughout the region, often impenetrable to outsiders, are easily understood across the board.

I have had a lifelong interest in the local Glens of Antrim history, myths and legends and I am constantly reminded of how the folklore, music and stories of this part of County Antrim are intertwined with those of the Hebridean Islands and Argyll. I think it is all but beyond doubt that many of the people now living in what was the ancient Kingdom of Dál Riada share ancestral, historical and cultural roots. These connections long pre-date the Plantation of Ulster in the seventeenth century, largely by Scottish settlers.

It is well documented that the McDonnells of Antrim are direct descendants of the twelfth-century Hiberno-Norse Warrior Somerled, and for 400 hundred years the clan were Lords of the Isles with strongholds, most notably on Islay and the Antrim coast. That people have been travelling back and forth across the sea between Ireland and Scotland for centuries is also evidenced throughout the Antrim Glens by the prevalence of family names like McAllister, McKeegan, McKinley, McAuley, and so forth.

From the misty Isle of Skye to the beautiful Glens of Antrim and everywhere in between, I have had the great pleasure of travelling through the islands and western highlands. It has been my experience that, in the main, the local people are possessed of identifiable, inherent characteristics: a love of the land and the natural world, hard-working, welcoming and warm (once you get by an initial reserve), loyal and loving to their own, and always up for a bit of craic – be it music, song or story.

As a traveller, I always feel as much at home in some far-flung Hebridean island as I do in the Glens of Antrim where I live. As a storyteller and a singer, I am most comfortable telling stories and singing songs that embrace the history and folklore and landscapes and people that I know best. By extension I include the rest of what was Dál Riada simply because it feels so culturally familiar to me.

In this collection I have tried to find interesting stories that reflect the diversity of folklore to be found throughout the region. Sadly, because of the limitations of this book, I have not been able include all of the many fascinating snippets of lore and legend I have come across. From faerie mice on Rhum to an imprisoned ghostly Norse maiden on Canna and many more fantastical creatures and characters, there is literally a story to be found on every rocky islet and in every locality, however small or remote.

As always, some places have yielded more than others either because of geography, local history, size of population or a combination of these factors. An island like Skye, with its ancient past, spectacularly mountainous landscapes and relatively large population, is obviously going to deliver more folklore than somewhere like Jura, for example, with a small number of inhabitants and a less-prominent historical role, beautiful and interesting as it is. Of course, it also depends on whether early collectors took an interest in a particular place or not, and if their stories were recorded or died out due to the migration of people or the encroachment of the modern world.

In my quest to find material I have combed through many older collections and reference books (for my full list see the sources section at the end of this book). We are all indebted to those who had the foresight to collect these stories and folklore first-hand, often in the old Gaelic, and set them down in print. Generally, debate still smoulders among storytellers, writers and academics about the ethics and value of writing down stories from the oral tradition. In a world that values oral storytelling much less than it once did, it is, in my opinion, essential to preserve these stories in whatever way we can and make them available to as wide an audience as possible.

The alternative is to risk the loss of these precious folk tales and all the beauty and wisdom that goes along with them. I do not subscribe to the view that I have heard espoused by some, that once a story is written down it somehow dies. How could that be? Written down, the words are there to be pored over and, filtered through the reader’s imagination, to delight and inspire. From the page they can be lifted, reimagined and retold at any time by anyone. It does not go without saying, however, that the storyteller must pay all due respect to the folkloric conventions of the culture from which the story has come. This was unconsciously intrinsic to tellers of the oral tradition but could be easily and innocently overlooked when working from written source material.

In any case, the folk tales in this anthology have already been written down in some form another, and in some cases hundreds of years ago. For my part, I have felt the need to rework every story to a lesser or greater degree, whether to make the archaic language more accessible, or the narrative flow better, or simply to breathe new energy into the story by way of a little judicious creativity. For this I make no apology. My brief was to reimagine and rework these old stories to suit the tastes of a modern audience. I believe this continuous process keeps the stories alive, interesting and relevant to successive generations of storytellers and students of folklore. Besides, it is my strong conviction that every storyteller must imbue the tale they are telling with their own personality and style, while at the same time – and it’s worth mentioning again – staying true to the tradition. This is what I have endeavoured to do and, I hope, achieved.

The researching and writing of this book has, as always, been very satisfying, but the sheer joy and excitement of revisiting many of the spectacular land and seascapes from which the stories originate is always tremendously emotional and special. This is especially so for me when I visit the Western Isles because I have fond memories of my father reminiscing about the Sea of the Hebrides and her many beautiful islands and moods. His ship patrolled these waters during the latter half of the Second World War, training the Atlantic convoy escort groups, meeting incoming convoy ships and guiding them to the safer waters of the Irish Sea, and hunting lone-wolf U-boats.

Today, standing on the cliff tops at Fairhead looking out across the swirling sound to Rathlin; or wandering among the grassy sand dunes on Islay listening to the myriad voices of geese and swans; or catching glimpses of eagles and otters on the wild Isle of Mull; or getting up close to whales in the rich waters around the Tresnish Islands; or imagining the presence of monks and Vikings among the ancient ruins of Iona; or scrambling up rugged mountain tracks to discover breathtaking views in the mighty Cuillins of Skye are all grand and wonderful experiences.

I hope some of that wonder comes through in these old stories. I hope, too, that readers might feel the urge to come and visit some of these hauntingly beautiful places and feel a little of the magic for themselves. Perhaps some will even be inspired to retell one or two of these old and enchanting stories to a rapt audience in a bothy some evening by the light of candle or over a wee dram of whisky. Sláinte …

Colin Urwin

Glenarm

December 2024

SKYE

1. Sgáithach and Cú Chulainn

This story forms part of the Ulster or Red Branch Cycle: a collection of medieval Irish heroic legends and sagas that is one of the four cycles of Irish mythology. Mainly featuring the Uliad and the mythical Ulster king, Conchobar mac Nessa, enthroned at Emain Macha, and Cú Chulainn, the warrior-hero endowed with superhuman powers, it first appears in written form in Lebor na hUidre – Book of the Dun Cow, c.1106, and later the Book of Leinster, c.1160. The stories are thought by some, however, to be up to five or more centuries older than this.

This version is compiled from various sources including that found in Otto F. Swire’s book, Skye, The Island and its Legends (Blackie & Son Limited, Glasgow, 1961).

Sgáithach, which means Shadow in the old Gaelic, was an ancient warrior queen. Some even say she was a goddess possessed of the power to convey brave warriors killed in battle to Tír na nÓg – Land of the Forever Young. She was known to be undefeated in battle and was famous throughout the lands of the Gael and far beyond. Exactly when she came to dwell among the wild rugged mountains of the island that would bear her name is not known, but come to the Isle of Skye she did.

She chose as her residence a place near Tarskavaig on the south-west coast of Skye. It was and still is unequalled for its raw beauty and commanding views over the sea. Here she built a fort known as Dún Sgáith – Fortress of Shadow. She founded a school where warriors, already proven in battle, could study for a year and become even more practised in certain martial arts. They learned how to vault over the walls of fortresses using only a hazel pole, how to fight underwater and, finally, how to take up and use Sgáithach’s deadly barbed throwing spear, the Gáe Bulg. Many proved themselves unworthy and did not survive, for the training was even more fierce than any real battle.

Perhaps Sgáithach’s most famous student was the great hero and guardian of Ulster, Cú Chulainn. His reputation as a fearless and ferocious warrior was unrivalled. He defeated whole armies single-handedly, and it was said that after battle three ice cold vats of water had to be prepared for him. When he immersed himself in the first it evaporated as steam, the second boiled over like a pot on an untended fire and the third came to an agreeable temperature fit to wash the blood and sweat from his body.

But let us not run ahead of the story. Before all this, Cú Chulainn fell in love with Emer, the beautiful daughter of an Ulster chieftain. Emer’s father, Forgall, disapproved of the match and only agreed to their marriage on the condition that Cú Chulainn would enter training as a warrior with Sgáithach. In his heart of hearts, he hoped his daughter’s young suitor would fail and never return. But Cú Chulainn was born to be a hero.

To begin with, Sgáithach all but ignored the strange upstart youngster who had travelled with his compatriots over the sea from Ulster. To impress her, Cú Chulainn soon attracted trouble and tempest like moths to a flame. In a spirited mock fight that lasted two days and nights, Cú Chulainn accidentally broke the fingers of Sgáithach’s warrior daughter, Uathach. She cried out in pain and her suitor, Cochar Croibhe, ran to her side. Seeing her injured, and to prove his abiding love, he challenged Cú Chulainn to a duel of single combat. Uathach protested, but the die was cast. Cú Chulainn easily defeated Cochar Croibhe and slew him without mercy.

To make up for this misdeed, Cú Chulainn offered to shoulder Cochar Croibhe’s responsibilities, but he soon became Uathach’s lover, apparently forgetting all about Emer, his betrothed back in Ulster. Eventually, Sgáithach was compelled to promise her daughter to Cú Chulainn and, perhaps feeling a sense of loyalty to his future mother-in-law, or to gain her approval further, he challenged Sgáithach’s fearsome rival sister, Aífe. Making use of little distracting lies, he defeated her in combat. With the blade of his sword at her throat, he demanded Aífe cease hostilities with her sister forthwith and, as if to seal the bargain, to allow him to impregnate her. In return for her life, Aífe agreed and later gave birth to Cú Chulainn’s son, Connla – but this is another chapter of a very long story.

Greatly displeased with Cú Chulainn, Sgáithach descended from Dún Sgáith in a violent rage and challenged him to combat herself.

‘Come and learn all ye heroes,’ she cried, ‘for never will ye see the likes of this again.’

Then the two mighty warriors clashed. They fought for three days and three nights over mountain, moor and marsh, but neither could gain the upper hand.

Uathach could see that her mother meant to fight to the death if necessary. She called for some sour hind’s milk and made the crowdie cheese that was her mother’s favourite. She baked a loaf and wafted the pleasant smell of the fresh, warm bread in the direction of the two combatants. She begged them to leave off their fighting and to come and refresh themselves, but they were like two red deer stags with their antlers locked in battle.

Then Uathach called for a fresh salmon. She cooked it over an open fire until the flesh was pink and moist and so tender that it fell from the bones. The skin was golden brown and crisp, and the smell so delicious that wolves salivated and howled for miles around. But neither Cú Chulainn nor Sgáithach would relent.

At last, Uathach roasted a wild boar on a spit. She stuffed it with hazelnuts gathered from the trees that grew by a burn on the side of a hill called Broc-Bheinn. The nuts were long known to be the source of great wisdom to anyone who ate them. As soon as the smell of those roasting hazelnuts reached the nostrils of Cú Chulainn and Sgáithach it came to them both in the same instant that if they ate of those nuts they would gain the knowledge and wisdom to overcome any rival. And so, they agreed to lay down their arms and take a little refreshment.

At first they ignored the salmon and the bread and the cheese. They even ignored the wild boar. They went straight to the hazelnuts, and the moment they ate them both warriors realised that neither would ever get the better of the other in combat.

They rose from their meal sated and, to everyone’s surprise, they did not pick up their weapons. Instead, they kissed and embraced one another. Between them they made a solemn promise of peace. They swore that if ever one needed the other’s help then all they had to do was ask and it would be given, ‘Even,’ they vowed, ‘if the heavens should fall and we be crushed.’

It is often whispered that Sgáithach took Cú Chulainn as her lover that night. But soon afterwards Cú Chulainn had to return to Ulster, where his exploits became, quite literally, the stuff of legend. Sgáithach remained on the Isle of Skye for the rest of her long life, but an unbreakable bond had been formed between her and Cú Chulainn.

Whether or not one ever called on the other for help, no one really knows. All I can tell you is that as a mark of respect and the deep affection Sgáithach bore for her ally and, perhaps, lover, she called the mountains of Skye Cú Chulainn’s Hills in his memory. And that is the name they bear to this very day.

2. The Swan Maiden of Skye

This remarkable and heart-rending story was found in Otto F. Swire’s The Inner Hebrides and their Legends (Collins, London and Glasgow, 1964). Caught between two worlds, the child is a damned soul and even today this story is bound to resonate with any individual or group of people who find themselves in a comparable situation.

There are similar stories where some otherworldly female entity agrees to marry a mortal man but only on certain conditions. The male character seems always bound to fail to keep the conditions or promises he makes but we cannot help wishing that he will succeed. This story is, in my opinion, among the very best and most beautiful of that genre.

Many centuries ago, down near the little sheltered bay of Gesto in the west of Skye, there lived a handsome young fisherman called Hamish. Day after day he went out in his currach like the other men. When all around were hauling in the good eating fish like cod and mackerel and herring, his net was empty but for dogfish and bony wrasse.

One evening, as he was returning home yet again with little to show for all his labours, he cursed his luck at the top of his lungs and vowed never to return to the sea. Just then he saw something glowing in the gathering dusk. It was like the light of a silvery moon behind a whisp of cloud slowly coming towards him over the water. Mesmerised, Hamish stood up in his currach. As he did so the strange light slowly took the shape of the most beautiful young maiden he could have ever imagined. She was clad all in flowing white. Her skin was just as pale and her long hair had a soft flaxen tint. The only other colours in this pale vision of a woman were the rosy-red of her lips and her eyes as black as ink.

Hamish was completely spellbound by the young maiden, so beautiful and strange was she. But before he could gather his thoughts or feel any kind of fear she spoke to him.

‘Hamish I beg you, do not give up your fishing. Come back to the sea and I promise good fortune will follow you.’

With that the vision of the maiden faded from view and was gone. From that moment onwards Hamish cared not whether he caught any fish or went hungry. All he could think of was the young woman. Every waking hour he ached for her and little he slept dreaming about her, such was his burning desire. Each and every day he went out fishing, but always he searched for her and hoped she would appear again.

Hamish began to prosper as his luck turned and many a young maid round and about kept her eye on him. Any one of them would have gladly taken him for a husband, but one lassie had long set her heart on him and let it be known that she meant to have Hamish come hell or high water. Anyone with half an eye could see how she flirted with him and dallied around him, but he was blind to her attentions.

This day Hamish went out in his currach from Gesto Bay to where he had first seen the maiden. When he was far from land, he laid up his oars. No fishing did he undertake. He just sat there, rocked by the gentle waves, searching the horizon and waiting for darkness to come as he drifted with the tide. Eventually, when his passion and pulse was racing with the fever of desire, he stood up in his currach and with his arms outspread he called out to her.

‘Oh, beautiful white maiden, please show yourself to me. I am sick for the love of thee. I would rather die than live my life without you.’

With that, Hamish made to step over the gunwale of his currach into the water. As he did so he suddenly caught sight of a swan pushing itself with great speed through the water towards him. It came alongside and Hamish stepped out onto its back. Gracefully, the huge bird carried him to shore. The moment the swan touched land it took the form of the beautiful young maiden, and she began to speak breathlessly.

‘I could not come to you again, Hamish, until you proved that your love for me was stronger than your fear of death. Now may I declare my love for you. My heart was broken that night you vowed never to return to the sea again. I had to show myself to you. Now I can stay with you in my mortal form forever.’

Hamish and the young woman were locked in each other’s arms for a long time.

‘Will you marry me?’ he whispered.

‘We can be married, but you must promise me something first.’

‘Anything, my love. I will do anything for you.’

‘Never must you ask my name or from where I have come. Promise me this.’

Well, Hamish was so in love with the swan maiden that he would have promised her the Earth and the moon and the stars.

‘I swear on the graves of our unborn children, I will die before I break my promise to thee,’ he said, and she willingly took him at his word.

Hamish and the maiden were married, and never were a couple so blissfully happy or so in love with one another. They were joined at the hip, and never did an unpleasant word passed between them.

Time passed and soon Hamish and his wife were blessed with a child. The baby boy was the sweet fruit of their love together and neither could have been happier. Most people wished them well, but not so the young woman who had wanted to marry Hamish. She was consumed by jealousy and at every opportunity she cast slurs on Hamish’s wife and dripped poison into the ear of anyone who would listen. One day she contrived to meet Hamish down by the shore as he worked at his currach.

‘How sad for that wee laddie of yours that he’ll never know his mother’s name or where on this Earth he came from,’ she said carelessly.

‘Of course he will know,’ answered Hamish, suddenly angered by her words.

‘How can he, when his mother has played you for a fool while she keeps all her secrets and makes you keep your promise?’ she spat.

Having planted the seed, the woman walked away, content with her work.

Hamish pondered the words all day while he toiled, and as he did he became more and more aggrieved at the seeming injustice of his wife’s conditions on their love. When he came home from fishing that evening he was in a dark mood.

‘I have been thinking, wife,’ he said at their supper table, ‘how unfair it is that you keep all these secrets from me, and now our son too. How is he to grow up not knowing his mother’s name or from where she came?’

‘Hamish, before we were married you swore that you would die before breaking your promise,’ said his wife, with her lips trembling.

‘Aye well, that was then, this is now. No son of mine will be reared not knowing who his mother is or even her name,’ Hamish roared, and he banged his fist on the table.

Hamish’s wife rose from the table. She lifted her child from the cradle and departed without another word. All that she left on the covers of their bed was a single white swan’s feather.