Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Folk Tales

- Sprache: Englisch

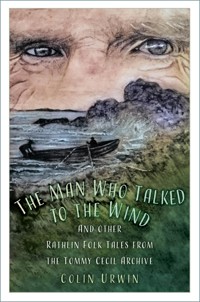

Swept by strong ocean currents and ferocious storms, Rathlin Island is mysterious and hauntingly beautiful. Lying just six miles off the north coast of County Antrim, it is the most northerly inhabited island of Ireland. Once home to prehistoric hunter-gatherers, its inhabitants have endured Viking raids, medieval massacres, famine and emigration. As farmers, fishermen and seafarers, they are resourceful, independent and proud – and they have always enjoyed a good story. Drawing on Irish and Scottish traditions, Rathlin has a rich folk heritage all its own. Much of it may have been lost but for one island man – Tommy Cecil. Best known for rescuing Sir Richard Branson after his hot-air balloon ditched into the sea off Rathlin, Cecil was also instrumental in saving many of the island's old stories. Taken from recordings held in the Ulster Folk Museum, this unique collection brings these stories to print for the first time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 199

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Colin Urwin, 2024

The right of Colin Urwin to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 819 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

Sea Call

The sea knows your name

Where you are

And how you came

To love the depths of it

The turning tides rise and fall

In all the dreams you dreamt

You heard its call

It flowed and roared

Across the axis of your heart

Into the dark blue lights of every wave

That captured your soul

The heaping waves upon the shore

You lingered by

Watching the mighty seabirds fly

Until you dived again to find

Your hidden world

The sea will not mourn for you

It knows your name

And where you are

Singing still

In deepest depths

And chanting waves

Its immortal song

For you

Mary Cecil

CONTENTS

Foreword by Linda-May Ballard

Introduction

Notes on the Stories

The First Monk

The Man in the Mist

The Old Hag of Rathlin

The Fisherman and the Mermaid

The Old Man of Rathlin

The Viking, the Falcon and the Old Man of Rathlin

The Viking and the Old Hag

The Three Stones

The Faerie Midwife

The Hunting Party and the Hare

A Lucky Escape

The Fisherman and the Cat

A Priest’s Curse

The Man Who Talked to the Wind

From Beyond the Senses

Massacre on Rathlin

The Woman Who Could Rise the Wind

The Peat Cutter

The Courig Glashin

The Rathlin Faeries

Ceilidhs and Customs

Eliza Brown and the Hireling

The Outcast Returned

An Capall Cailín

A Secret of the Children of Lir

Ravens and Rivalry

The First Ravens

The Seals of Dún na Gael

The Vanishing Isle

The Third Wave

The Brave Brother

Headland of the Fair Colleen

The Pot of Gold

The Viking with Rathlin Roots

The Warrior Woman

The Stolen Twin

The Ember, the Falcon and the Wolf

A Native Son Returned

Further Reading

FOREWORD

Almost half a century ago, a proposal I put forward to collect folk tales on Rathlin Island was accepted as part of my work programme. Equipped with my Ulster Folk and Transport Museum issue Uher tape recorder and a few essentials (which included a tent, as in those days there was no guest house or other tourist accommodation on the island), I drove to Ballycastle and caught the ferry, not entirely sure when I would be making my return trip. In those days, visits to Rathlin were even more heavily dependent on the weather than they are now. The trip took an hour. I watched spellbound as slowly we drew closer to the island and at last Church Bay was in sight.

My trusted, and usually infallible, method at that time for striking up acquaintanceships with potential storytellers was to go to the local shop, place my tape recorder prominently on the counter and buy myself a treat, usually a bar of chocolate. Inevitably, someone would ask me what the machine was for. I would explain my mission and was always directed to someone with a gift for narrative. So naturally, once my tent was pitched securely, I headed for the island’s nearby shop.

My method failed me. No one paid the slightest attention to my recording equipment and eventually I had to explain to the young lady behind the counter my reason for being on the island. In a Scottish accent perhaps more marked then than it is now, she told me in no uncertain terms that there were books about the island I could consult. Swallowing hard, I responded that I had indeed read them, but I was hoping to learn about the island from the perspective of the islanders themselves, which didn’t seem to me to be very well represented in existing publications. I was given directions to a nearby house and told to be there at nine o’clock where I could talk to her husband, who should be back from scuba diving by then.

By this time, my heart had sunk to my boots. I had been collecting folklore for about three years by this stage and unconsciously subscribed to the prevailing certainty that stories were the sole preserve of elderly gentlemen, which, unless this lady had married someone very considerably her senior, her husband could not possibly be. And what on earth would a scuba diver know about folklore? Furthermore, the lady’s accent clearly revealed that she hailed from somewhere other than the island. I loaded a single tape into my machine, mainly out of politeness. At the appointed time, hoping at least that the person I was going to meet could send me on to a more suitably qualified individual, I presented myself at the house to which I had earlier been directed.

By the time I left it was the small hours of the morning and I was giddy with delight, I had been treated with much more hospitality than I could possibly have merited by the lady herself. I had learned how entirely misguided all my preconceptions were. I had met the totally astonishing, spellbinding Thomas Cecil and his equally remarkable wife, Mary. Best of all, perhaps, I had an invitation to return to the house a few evenings later. For that next visit, I brought an adequate supply of tapes and batteries.

That first trip was made in the summer months, but it quickly became apparent that, as Thomas had a vast repertoire, it would be necessary to return. The best time to do so would be in the winter when the weather would mean that Thomas would not be so busy with the demands of his diving work. That posed another challenge, for during winter it was very hard to predict when the ferry – which Thomas and his brother-in-law Neil also provided – would run. Mary kindly came to my aid. If I indicated when I might come out to the island, she would telephone and let me know when Thomas was going to operate the ferry. With this arrangement in place, I used to keep a bag packed and ready so I could jump into my car and drive to Ballycastle when Mary’s calls came through.

I clearly remember one occasion when, in atrocious weather, Thomas needed to bring a bridegroom from the island to Ballycastle for his wedding. A call from Mary and I was on my way north to make the return voyage. It was the only time Thomas and Neil insisted I stay in the wheelhouse and that I saw charts unrolled and ready for consultation. In those days my husband, Ronnie, had working arrangements sufficiently flexible to permit him to be able to come to the island with me and we passed many, many memorable and magical winter evenings in the warmth of the home of Thomas and Mary: a warmth that was characterised as much by their personalities and kindness as it was by the glowing fire on the hearth.

Thomas had garnered his vast repertoire of narrative and other lore from his great uncle Robert and from other sources, including his father. As a young boy he had the presence of mind to record much of this in notebooks, but a great deal of it he had committed effortlessly to memory. It may seem strange that, for a storyteller, Thomas was not a man to waste words, and this was reflected in his spare, often laconic and always remarkably graceful narrative style. While his father never permitted me to record him directly, after I had visited the island a few times, he began to tell Thomas narratives that were to be passed on to me. I remember the first time I heard one of these, prefaced by Thomas with, ‘My father said I could pass this one on to that girl from the museum.’

Academics have long debated the challenges of transcribing folk narrative so that it can be presented on the page in written form. Some have devised complex and ingenious methods for indicating cadence and other matters integral to oral form. In presenting Thomas’ stories in written form, Colin has found a different solution and has given them a literary treatment. There are, of course, precedents, such as Hans Christian Andersen, for doing exactly this and Colin, who himself is well known as a storyteller, has done it with elegance and skill. As he explains, the cadences of his written words are his own: one storyteller embracing the repertoire of another in a seamless way as the tales are transmitted in written rather than oral form.

Colin has also applied his own extensive knowledge of the island’s folklore so that he and Thomas can join in collaboration to prepare the stories for publication. How I would enjoy it if I might be permitted to join them in one of those evenings Colin imagines. Meanwhile, as Colin explains, Thomas’ stories themselves can be accessed in the archives held by the Ulster Folk Museum.

Among his selection of stories from Thomas’ repertoire, Colin includes one he has entitled ‘The Third Wave’, explaining in his introductory note about the tradition on Rathlin of the third wave being the largest. Thomas assured me many times that he always counted the waves himself. He also told me of how long ago smugglers, when chased by the excise men, used to take advantage of a narrow gap at a certain place near the West End between some rock stacks and the island itself. It was only at the last minute that the gap would appear as from almost any vantage point the stacks seemed to be a continuous line of cliff along the coastline. The smugglers would seem to have vanished but instead had used their navigational skills to pull clear and escape their pursuers.

Thomas often promised that he would take me round the island by sea, and one jewel bright summer day he invited me to accompany him in his motorised dory. Of itself, this was an unforgettable occasion in an extraordinarily beautiful place, and that alone would be enough to fix it forever in my memory. At one point on our journey, Thomas cut the boat’s motor and I thought he was just taking a few minutes to enjoy the tranquillity of the extraordinary afternoon. Then I realised he was concentrating with great intensity, and counting, almost under his breath. Silently, I began counting too, ‘one, two, three: one, two, three …’ A huge wave swelled under the little craft, and suddenly Thomas started the motor once more. The wave carried us toward what appeared to be a solid face of high and unforgiving cliff, but at the last minute a gap opened between the stacks, and we were through. Folklore made vibrantly real by a most remarkable person, a man one implicitly trusted with one’s life.

Linda-May BallardMay 2024

INTRODUCTION

Tommy Cecil (1946–97) was born and bred on Rathlin Island, just off the north coast of Ireland. The man was many things to many people. First and foremost, he was a faithful husband to his wife Mary and a loving father to his three sons and four daughters. He was a loyal friend to a few and well known by his island neighbours. Among his many colleagues and acquaintances, he could call on fishermen, sailors, farmers, artists, journalists, politicians, celebrities, and countless other individuals from all walks of life. To them he was a larger-than-life character who, even in his tragically foreshortened lifetime, attained legendary status. To understand the man behind the legend we must first visit his native island.

Rathlin, or the Enchanted Island as it is sometimes known, sits like a giant well-placed stepping stone between Ireland and Scotland. It is approximately 3 miles from the Irish mainland and 15 from the Mull of Kintyre. The island is a reverse L shape turned 90 degrees anticlockwise. It measures 4 miles long from east to west and 2½ miles from north to south. Its highest point, Slieveard, often referred to as ‘the mountain’ by islanders, is 440ft above sea level. Due to many factors, the population has fluctuated greatly over the years. During the Irish Famine five hundred people left in one day. At time of writing there are about one hundred and twenty-five souls.

The island was home to Neolithic people, who made beautifully crafted axe heads from porcellanite – a highly valued hard black rock found in only in one other deposit on the mainland, at Tievebulliagh in the Glens of Antrim. In 2006 a Bronze Age cist grave was discovered during building work at the island’s pub. The grave contained human remains that carbon dating showed to be from about 2000 BC – a thousand years before the arrival of the Celts, who were widely thought to be the ancestors of modern Irish people. DNA analysis, however, revealed a genetic continuum with the Rathlin remains and today’s population, and this turned the previously held archaeological theory and timeline on its head.

More than two millennia later and Rathlin was at the centre of the ancient Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riada. This realm ran from the north-east of County Antrim up to the Isle of Skye, taking in the Inner Hebrides and a huge swathe of the Argyll coast. For hundreds of years Rathlin and her resources were fought over by Vikings, chieftains and Sassenachs. Its ownership was long disputed between Ireland and Scotland and, in local lore at least, settlement was only reached by dint of the fact that, like mainland Ireland, no snakes existed on Rathlin. It was purchased from the Earl of Antrim by the Reverend John Gage in 1746 and an old Rathlin story goes that Gage, having got wind that a party of islanders were en route to do a deal with Lord Antrim themselves, purchased the island from under their noses (Ultster Folk Museum archive reference R80.30.19/4/80). In any case, Gage and his descendants owned Rathlin and largely controlled the fortunes of the islanders up until relatively recent times.

Many species of animal make Rathlin their home. The famous golden hare – a rare and distinct light-coloured, blue-eyed variation of the Irish hare – is found on Rathlin. All kinds of wonderful marine life from whales and dolphins to basking sharks often appear around its coast. Spectacular blue fin tuna and thresher sharks have both been seen and captured on camera in recent years. For millennia, tens of thousands of guillemots and gulls have come to breed on the cliffs at Kebble near the West Lighthouse, now an RSPB reserve. Once, in the not-too-distant past, the great seabird colonies provided islanders with a ready supply of meat and eggs. Nowadays, local people and tourists alike eagerly await the seabird colonies coming to life each spring. Puffins are a favourite with the birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, who come from far and wide to enjoy the spectacle. There are other bird rarities including the once common corncrakes that have made something of a comeback after a few years of absence.

Like so many lovers of wildlife and wild places, I too was drawn to Rathlin several times over the last thirty odd years. In this modern era there have been some stark transformations, not least the removal of dozens of scrap vehicles and the building and renovation of numerous dwellings. The inhabitants have watched as their island home has developed from a neglected backwater into a thriving tourist attraction. As would be the case with any group of people, some approve wholeheartedly while others might have preferred to take things a little slower. One islander who was always eager to bring about positive change for the benefit of the whole Rathlin community, however, was Tommy Cecil. Well known for his vision, passion and dynamism, he could come across as more than a little pushy and argumentative. But if he held strong opinions he was not opinionated, and he was nothing if not a deliberate man.

At a time when the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles’ were raging on the mainland and some people were tentatively arguing that Catholic and Protestant children should not be segregated in school, Tommy Cecil, along with his wife Mary, were fervent advocates for integrated education on the island and demanded that right for their own seven children.

Besides being a busy family man and vigorous community campaigner, seafaring and adventure were in Tommy Cecil’s blood. He was an avid scuba diver and in his youth he had been a deep-sea merchant man for a couple of years. Among other places, he sailed to Australia but having seen a bit of the world and saved some money he came back home to set himself up with a fishing boat and go into business with his friend and soon to be brother-in-law, Neil McCurdy.

Like all islanders, he had to be very resourceful. As well as fishing for lobsters among the wrecks that litter the waters around Rathlin, he skippered the island’s ferry boat for over twenty-five years. He carried the island children back and forth to school on the mainland. He fetched men to their work and brought back the mail. He took pregnant women and medical emergencies across the Sound in all kinds of weather, day and night. Over the years he briefly touched the lives of thousands of tourists. Many visitors to Rathlin fell under his spell and fondly remember his great store of home-grown knowledge and wit.

For years Tommy relentlessly canvassed for better and safer harbour facilities, only for his efforts to backfire. The government eventually heeded his calls but in the process robbed him of his livelihood and put the ferry service out to commercial tender, for which his vessel could not compete. Badly mauled but not beaten, in the early 1990s Tommy opened his own diving centre on Rathlin. Just as the fishermen do with the central character in the title story of this book, The Man Who Talked to The Wind, visiting scuba divers, both novice and experienced, always sought Tommy’s advice. His expert knowledge of the treacherous tides, currents and the wrecks around Rathlin (on which he published a book in 1990, The Harsh Winds of Rathlin) was second to none.

Some of the stories relating to Tommy Cecil’s many exploits have passed into island legend. Like the time he appeared as a witness for the prosecution in a case involving the shooting of a rare bird by a visiting sportsman. The fowl in question was a chough – a red-billed, red-legged member of the crow family – which afterwards became extinct on Rathlin. Tommy gave evidence to the effect that while out rowing in the bay he heard a shot. Seeing a bird falling into the sea, he rowed over. Realising it was a rare and protected species, he collected the specimen, which was now offered in evidence to the court. During cross-examination, council for the defence put it to Tommy that since he had only heard a shot, found a bird and subsequently saw the defendant with a shotgun, he could provide no evidence of causality. Tommy considered this proposition briefly before commenting, ‘Well, the chough didn’t commit suicide by shotgun.’ The man was convicted.

Perhaps Tommy was made most famous to the wider community for his role in the rescue of the billionaire businessman Sir Richard Branson. After crossing the Atlantic by balloon in record time and touching down briefly on Irish soil near Limavady in County Derry/Londonderry, the capsule carrying the tycoon was still being dragged along, dangerously out of control, by its huge balloon. Swooping low over the sea near Rathlin, it was spotted by Tommy, who set off in pursuit. When the capsule eventually ditched into the ocean Tommy was in position and managed to get a line on to it.

Next thing Tommy found himself in a potentially intimidating stand-off with a Royal Navy warship intent on salvaging the stricken craft. ‘Let go your line Paddy,’ an English sailor ordered condescendingly and followed with menacing threats when Tommy refused. Tommy took his camera out to record what might happen next. Only after an officer apologised and flashed the utmost civility did the indomitable Rathlin man back down and agree to relinquish his claim, saying, ‘If ye’d asked me nicely in the first place ...’ Before he let go the rope though, Tommy cheekily asked, ‘You wouldn’t happen to have a wee drop of petrol to get me home would you?’ His request was readily acceded to.

Shortly after, Sir Richard Branson visited the Cecil family home, where he dined on freshly caught lobster and was warmly regaled by Tommy and Mary. Later Sir Richard generously donated £25,000 towards the refurbishment of the Rathlin Manor House and funded a high-speed inshore rescue vessel for the island. During its maiden voyage from Ballycastle across the Sound, Sir Richard and accompanying journalists held on for grim death. Proudly at the helm was Tommy Cecil deftly steering the small craft over the waves at terrific speed, seemingly oblivious to the sheer terror being experienced by all those on board. One photographer was heard to sing ‘Abide with Me’!

Much less well known off the island was Tommy Cecil’s love and knowledge of Rathlin folklore. From an early age he had been exposed to the oral storytelling tradition that still survived into the 1950s and ’60s. His parents and grandparents and his great uncle Robert McCormick used to gather with other islanders and lighthouse keepers to ceilidh – tell stories and gossip to pass an evening. Listening wide-eyed, sometimes when he should have been in bed sleeping, Tommy gained a huge repertoire of island folk tales organically implanted in his boyhood. He did write some down, which was frowned upon, particularly by his great uncle, but by his own admission he had probably forgotten many more than he remembered.

Though clever and naturally questioning, Tommy was superstitious in ways some might now find absurd. For example, he would not allow playing cards in his house – a common enough taboo in Ireland even yet. He had been brought up with stories where the Devil or some other malignant spirit often appeared when cards were being played. But he had also once had a strange experience himself and did not shy away from talking candidly about it.

While at sea years before, he travelled to the Far East. During the voyage a crewmate had been involved in some sort of violent altercation ashore and been killed as a result. Later, as his ship was ploughing through the Indian Ocean, Tommy was playing cards, as the men often did to pass the time. In the middle of the game, he went back to his cabin and walking along the passageway encountered the apparition of his young dead crewmate coming towards him. Tommy rubbed shoulders with the ghost and distinctly recalled the sensation of the physical contact. Associating this strange happening with the card playing, and probably remembering the old stories from his youth, he never again touched the ‘devil’s cards’, nor would he suffer them under his roof (R80.30. 19/4/80).

Another unusual incident highlights Tommy’s acceptance of what some might describe as superstition. One summer, his uncle was visiting the island from the mainland. They were out fishing in a boat enjoying the fine weather when Tommy heard seals calling. It was an unearthly wailing and moaning not normally heard during the day or at that time of the year.