Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

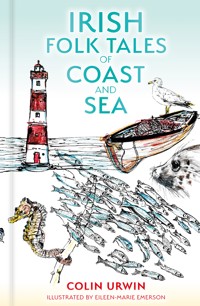

A wild frontier of mighty headlands, sheer crags rising from the sea and miles of lonely golden sands – Ireland's coastline is foreboding, exhilarating and achingly beautiful. Men and women have lived and loved and died in this harsh but bountiful environment. Through it all they have told tales to entertain themselves, to pass on wisdom and to banish despair. It is little wonder that our richest folklore is woven into this island's rugged and romantic coastline. Brought together and reimagined by modern-day seanchaí Colin Urwin, this collection includes some of the most enchanting, strange and poignant folk tales to be found on this ancient isle.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 278

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Colin Urwin, 2024

Illustrations © E.M. Emerson, 2024

The right of Colin Urwin to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 773 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

DEDICATION

To my wife Carol for her patience, and to our grandchildren – Islay, Maria, Oliver, Oscar, Freida, Elle and Luke. May they know the joy of story.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

PROVINCE OF ULSTER

County Down

Fearghus mac Léti and the Muirdris

The Mermaid and the Monk

County Antrim

The Cushendall Horse Dealer

Finn McCool and the Giant’s Causeway

The Phantom Boat

County Derry

The Gem of the Roe

A Tragic Tale of Two Sea Captains

County Donegal

Sean Gallagher and the Seal

The Faerie’s Due

The Cursing Stones

The Spailpín and the Red-Haired Man

PROVINCE OF CONNACHT

County Leitrim

The Earl’s Son of the Sea

County Sligo

The Inseparable Twins

Thady Rua O’Dowd and the Mermaid

The Black Horse of Enniscrone

County Mayo

The Greedy Fellow

The Bride’s Lament

A Smuggler’s Story

County Galway

Conán Maol and the Old Hag

The Claddagh Fishermen

The Claddagh Ring

PROVINCE OF MUNSTER

County Clare

The Voyage of Maoile Dhúin

The Sunken Village

County Limerick

The Shannon Mermaid and the Soldier

The Black Man

County Kerry

Tom Moore and the Sea Maiden

The Son of the Sea

Flory Cantillon’s Funeral

County Cork

The Clear Island Fisherman

Ruin and Rescue at Calf Rock

The Mermaid of Barley Cove

The Green Man of Templetrine

County Waterford

Father Spratt and the Marquess of Waterford

The Donegal Hole

PROVINCE OF LEINSTER

County Wexford

At the Head of Baginbun

The Faithful Cabin Boy

County Wicklow

A Maritime Mystery

The Romans in Bray

County Dublin

The Last Danes in Ireland

Rockabill and the Birth of the Boyne

A Pressed Man

County Meath

The Enchanted Cattle

County Louth

The Destruction of Cahir Linn

The Curse of Dónairt

Glossary

Sources

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am very grateful to fellow storyteller Tom Muir, and Nicola Guy, commissioning editor at The History Press, for having the faith in me to write this book.

For generously sharing their stories and sources, I am indebted to Eimear Burke, Madeline McCully, Masako Carey, Aindrias de Staic and his family, Máirín Mhic Lochlainn, Nuala Hayes, Kate Corkery, Jerry O’Neill, Philip Byrne and Janice Weatherspoon.

Thanks also go to Colum Sands, Aoife Demel – Storytellers of Ireland, Éilis Ni Dhuibhne, Staff at NI Libraries Larne Branch and Ailbe van der Heideat – Cnuasach Bhéaloideas Éireann/National Folklore Collection, University College Dublin.

INTRODUCTION

I was born and bred on the beautiful north-east coast of Ireland and have lived a stone’s throw from the sea my whole life. As a young boy, many happy summer days were spent fishing for crabs with a handline, gathering whelks, rock-pooling, beachcombing for shells and fossils, or just waiting for the tide to go out or come in.

The comings and goings of the cross-channel ferries from my hometown of Larne to Scotland and back, regulated my littoral activities almost as much as the ebb and flow of the tide. The bow wave from one of those ships could easily swamp a small punt or an inattentive boy up to his knees at low water looking for starfish and sea urchins.

A favourite walk along the coast road led adventuresome schoolboys to a place called the Devil’s Churn. As children we were told that the deep hole in the black rock through which the waves constantly spouted foam and hissing spray was bottomless. To fall in meant certain death for there was no escape! Even on a summer’s day it was always eerily cool and gave us the shivers. Up close, I could just imagine some living thing exhaling cold, damp breath in my face.

Local sea caves were said to be used for witchery and there were accounts of ghosts and other strange goings on. We delighted in all this lore and after dark tried to scare the wits out of each other retelling the stories we heard – the more macabre the better. But you always had to go home alone and I for one could never get the images out of my head. With the bedclothes pulled up to my chin, I tried to concentrate on the regular flashes from the Maiden’s Lighthouse – one, two, three – as the beam swept across our front bedroom window. Each flash cast shadows for just a moment before the pause of a few more seconds and the sequence of three began again. The counting always seemed to settle my feverish young imaginings and helped me to fall asleep.

I also remember well listening to the slow, steady haunting blare of the foghorn across the bay on Ferris Point, and hoping the mist would have cleared by morning so I could go fishing in the sun – it usually had. Later, the old fishermen who lived along that shore were glad of young fit lads to row their big wooden clinker-built boats. I was only too happy to oblige. Hand-pulling lobster pots, jigging for herring and mackerel or streaming for pollack, I was in my element.

Those old fishermen stoked my imagination with their stories about basking sharks and killer whales. Growing up, I often saw seals and occasionally little black porpoises but despite great hopes and all efforts I never encountered anything more exciting. There were tales about ships being wrecked by storms and drownings, and I was always wide-eyed and avid for more. A decade before I was born, the MV Princess Victoria coming from Stranraer in Scotland to my hometown had been lost along with 133 poor souls, including a family relative. For many years after, the terrible events of that day were often recounted by my mother – she was the storyteller in our family.

My father, who was in the Royal Navy during the Second World War, occasionally talked about some of the amazing natural wonders and historic events he had witnessed around our coast. There were old grainy black and white snapshots of German U-boats and years later he captured some cine-camera footage of an orca that had stranded itself in Larne Lough, recording the efforts of local lads to refloat it.

At one time in my youth, I thought I might pursue a career at sea, but life took me in another direction. I did enjoy one year working for a local fisherman pulling lobster pots and setting nets for, among other species, salmon and sea trout. We were not very successful from a commercial point of view, but it was one of the best experiences of my life. Forty years on it continues to inspire me, not least because my employer possessed a great wealth of local folk and fishing lore, which he liked to share. I still maintain a small boat and though I don’t get out on the water as often as I would like these days it is a link to the sea and my boyhood.

I loved the sound of the huge red foghorn on Ferris Point. Sadly, it is long gone – replaced, like the lighthouse keepers, by modern navigational technology. Those old fishermen I used to know and the vast shoals of herring and mackerel that came in every summer are gone too. But the ferries still travel back and forth to Scotland and there seem to be more and more small pleasure boats fishing for fewer and fewer fish.

Every day, no matter the weather, I walk along the coastal path near to where I live. Sometimes the sea is oily calm, sometimes wild and foreboding. I often catch glimpses of seals and dolphins and occasionally an otter. There are always gulls and cormorants, sometimes great northern divers and the rugged sea cliffs are home to ravens and peregrine falcons. I always breathe deeper and feel more inspired down by the shore.

Nowadays, I am very fortunate to make my living travelling the world telling stories and singing songs – though most often at events and festivals around the coast of Ireland. Most of my material is from the Glens of Antrim and related in some way to the sea, but I love hearing and collecting sea stories from other places too. Imagine my delight, then, when I was invited to write this book. It has truly been a labour of love – but then I always say that, with complete honesty, about my writing and storytelling.

I was given a few guidelines by the publisher. Firstly, of course, all the stories had to be Irish and of the sea and shore – in one or two instances I may have stretched the maritime connection a little, which is noted in the corresponding introductions. Secondly, the stories were to be written as I would tell them. For ease of reading, I have used a conventional literary form rather than attempt to replicate an oral telling style. (I apologise here for not using localised dialect and syntax as I move around the coast from county to county – I hope contributors and readers will understand.) Thirdly, I had to write an introductory paragraph or two for each story. Overall it was a relatively straightforward brief.

To this, however, I imposed a few more provisions on myself. As far as possible I wanted to visit all the places I was writing about. I also wanted the collection to be as diverse as I could make it and to include only stories not previously published in any of The History Press collections of folktales. By and large, I have followed this with only one or two exceptions, which are again noted in the introductions – some stories were just too good to bypass! Lastly, I tried to include as many stories as possible that I had originally heard from the mouths of storytellers I admire. The few I approached for stories were most accommodating and gracious. I am very grateful to them.

Of course, the forty-four stories contained here are by no means a definitive collection. I could easily have filled several volumes with Irish stories of coast and sea, but there was a limit to how many I could include. I considered a few factors when selecting each story but the most important question I always asked myself was, ‘would I like to tell it?’

I also felt compelled to represent every coastal county in Ireland, of which there are nineteen. Sadly, I have not been able to find a suitable story from County Kilkenny, which, technically, has a small coastline but does not have a vibrant seafaring tradition in the same way that, for example, County Mayo has. Due to geography and history, some counties simply have a bigger index of sea lore than others. Therefore, County Cork, with the longest and perhaps most varied coastline, is represented with four stories, while County Leitrim has only one. Starting with my native province of Ulster, and for no reason other than I had to start somewhere, I have travelled in an anticlockwise direction around the coast from County Down to County Louth.

Under the catch-all of folktales, the collection also includes myths and legends. I have made no attempt to categorise them according to their various story types. As I note in their introductions, two or three of the stories have been drawn from the historical record. In the main, these have been chosen because of some unusual folkloric aspect, element of mystery or just because they appealed to me. I have edited and reimagined all the stories according to my own tastes and the timbre of this book, often changing the title from that found in other renderings.

Some of these stories relate to incidents dating back over 100 years, some were first written down by monks a few centuries ago, and others, according to Professor Horace Beck, author of Folklore and the Sea, may have roots that go as far back as the Stone Age. Imagine that – an unbroken thread of story from the Neolithic to now. It is quite an extraordinary thought.

Researching these stories has expanded my repertoire and knowledge of Irish folklore in general and, of course, our spectacularly varied sea lore in particular. The writing of this book has highlighted just how much more there is for me to discover. I trust the reader will find the result interesting and entertaining, but above all I hope some might feel inspired to tell at least one of the stories they find within.

Colin UrwinGlenarmDecember 2023

PROVINCE OF ULSTER

County Down

FEARGHUS MAC LÉTI AND THE MUIRDRIS

This story dates to the seventh or eighth century. I first heard it told by my friend, storyteller, harpist and modern-day druid, Eimear Burke. She directed me to Irish Sagas edited by Myles Dillon (The Mercier Press, in collaboration with Raidió Teilifís Éireann,1968).

Here I found an analysis by D.A Binchy, professor of Irish linguistics and early Irish law. Binchy notes that the lúchorpáin, which is portrayed as some sort of mischievous water faerie, was the first representation of what would become known as the leprechaun in Irish literature.

It could be interpreted that the charm or wish granted to Fearghus is a caul – the membrane that encases a foetus and is sometimes still covering the head at birth. Until very recent times, cauls were cured and made into a kind of cap. Thus preserved, they were highly valued for it was believed they protected their owners against drowning, as they had done the child in the womb.

Twelve hundred years ago, when wild woods covered the land, and the bellow of rutting stags and the howl of wolves was heard throughout Erin, chieftains and clansmen lived uneasily alongside their neighbours. Druids and pagan gods held sway among the people. There were blood feuds and great feasts. Battles, bards and betrothals were commonplace and all for the gain of power and prestige.

At the time of our story, Fearghus mac Léti was a mighty chieftain whose sword was much feared. He was king of the Ulaid and not a man to be played carelessly. In times gone by, his neighbours to the south, the Féni, had quarrelled among themselves. Conn Cétchathach – Conn of the Hundred Battles – had prevailed, causing his clan rival Eochu Bélbuide – Eochu of the Yellow Lips – to flee and seek the protection of Fearghus, which was freely given.

Time passed and Eochu wished to return to his own land to make peace with Conn. As he travelled back home, he was set upon by six assassins and slain. Among his attackers was Conn’s son and, in a cruel twist, Eochu’s own grandson by his daughter, Dorn. Worse was to come, however. By murdering Eochu, the assassins had given great offence to Fearghus under whose protection Eochu still was.

Fearghus mac Léti and his warriors moved swiftly to punish the insult. The Féni could not stand against their more powerful neighbour and so, to settle the dispute peacefully, Conn humbly offered to make amends. The law required recompense and by rights this should have meant the lives of Conn’s son and the other assassins. Instead, the Féni’s prized possession of the coastal lands around Lough Rudraige (Dundrum Bay) in the shadow of Bairrche (the Mourne Mountains) were ceded to Fearghus and the Ulaid.

In return for the life of Eochu’s grandson, the sixth assassin, his mother, Dorn, offered herself. Although, or perhaps because, she was of high birth, Fearghus accepted and took her as a slave. His honour and the law satisfied, Fearghus returned to Ulster and his stronghold at Emain Macha. The Ulaid were well pleased with their chieftain’s latest gains.

Fearghus travelled by chariot to survey his new domain. When he came down to the shore he marvelled at the breathtaking beauty of his surroundings. After some sustenance, Fearghus and his charioteer lay down to take their rest on the sandy beach. Without fear of being assailed, the mighty chieftain fell into restful slumber.

Sometime later, Fearghus felt cold water lapping at his feet. He awoke with a start thinking the tide must have come in. But, as he regained his wits, he saw that he had been dragged down to the water’s edge by a band of little men no taller than a hare. Suddenly alert to the danger, he snatched up three of his tormentors and knowing they were lúchorpáin – mischievous little leprechauns – he held them fast in his great hands.

‘Let us go,’ pleaded one.

‘I will,’ said Fearghus, ‘but not until you grant me a gift to make amends.’

His captives readily agreed and Fearghus carelessly wished to be able to breathe under water. In an instant, he was granted a charm by the little men and, possessed of the power to breathe like a fish, he felt himself even more emboldened than before.

‘But mind, you must not try it here in Lough Rudraige,’ said the wee man, ‘for if you do you will surely rue the day.’

Time passed, and whether Fearghus was not afraid of the lúchorpáin’s warning or just could not resist the temptation of the forbidden, he took his caul and went into the waters of Lough Rudraige. As he dived down into the depths full of life and wonder he saw beautifully coloured fish that darted here and there. There were strange creatures with tentacles and huge unblinking eyes, and yet others with shining black armour and claws that gripped painfully. Then from out of the depths loomed a terrible, gigantic beast. Its great body enlarged and deflated like a giant set of blacksmith’s bellows. Its huge, cavernous mouth gaped as if to swallow Fearghus whole in one gulp. It was a Muirdris – the grotesque sea monster seen by few and dreaded by all who had heard tell of it.

Face to face with the creature, Fearghus mac Léti, the great chieftain who was so bold and unafraid on the field of battle and against any enemy, was struck by sheer terror. Unarmed and frightened beyond any worldly dread, he swam for his life. As he reached the shore exhausted and panting like a hunted animal, he called for help. When Fearghus’s servant laid eyes upon his chieftain, he was horrified for his master’s face had been so contorted by fear he was horribly disfigured. It was later whispered that his mouth had been twisted almost to the back of his head.

On dry land, Fearghus was dazed and staggering on his feet. He had never experienced such terror, nor had he ever before recoiled from an enemy, but then he had never been faced with such an adversary as the Muirdris. He could sense that something within his own being had altered.

‘I feel strange,’ he said to his servant. ‘Look at me, am I changed?’

‘Perhaps a little pale and drawn my lord, but nothing that a good night’s rest will not put right by morning,’ lied the servant, hiding his real concerns.

Fearghus lay down in the bottom of his chariot and, wearied and weakened by the ordeal, fell instantly into a deep sleep. His charioteer did not spare the horses on their way back to Emain Macha. All the way he feared for his chieftain for he knew, as everyone did, that the king had to be unblemished. One small disfigurement of any kind, even a scar gained in battle, would oblige the king to stand aside.

While Fearghus still slept, it fell to his charioteer to tell the elders and druids what had befallen their beloved chieftain. The news caused great consternation, but, after much debate, everyone was agreed. They refused to let a petty and unjust law, and the king’s own burning sense of pride and honour, be his downfall. The truth of Fearghus’s deformity would have to be kept from him.

From now on, they decreed, Fearghus would only be tended by a close circle of faithful servants. Anyone of low birth and who could not be completely trusted was banished from the court. He would never be allowed to look into a basin of water again for fear that he might see his own reflection. Dorn, his enslaved servant, being of high birth, would wash his hair while he reclined.

Seven years passed and Fearghus remained the much-loved king of the Ulaid, though he was often short-tempered because of the seemingly endless coddling imposed on him by his advisers and servants. He never suspected their well-meaning deceit, not for a moment. One day, as the long-suffering Dorn prepared to wash Fearghus’s hair, he became impatient with her and struck her with a switch. It was one indignity too many for her.

‘You dare to insult me!’ she spat. ‘You! Whose face is twisted by your own fear. You are not even fit to wash the feet of a king. You can no more hide your spinelessness than I can my contempt for ye.’

Her rage unleased, Dorn taunted Fearghus all the more.

‘Here, see for yourself,’ she said, and offered Fearghus the basin of water to look upon his reflection.

Even in his rippling watery reflection, Fearghus could see he was as she said. In a fit of rage, he drew his famous sword and with all his strength he brought the blade down on Dorn’s head and cleaved her in two. In that instant, was she released from years of enslavement and all the bitter mortifications she had endured. By his own actions, Fearghus proved, at least to himself, that he had become unworthy of the Ulaidian kingship. Straightaway he flew to the shores of Lough Rudraige intent on redemption.

‘’Twas fear of the Muirdris twisted my features, only by facing that which I fear most can I be freed,’ he cried.

Wearing his caul and with sword in hand he rushed into the water to do battle with his nemesis. For a day and a night, Fearghus fought the Muirdris while his clansmen gathered along the water’s edge. The sea boiled and frothed, and great waves broke upon the shore. All who witnessed those sights and sounds were gripped with awe and wonder.

Eventually, Fearghus staggered from the sea gasping for breath, his chest heaving. He held the giant bloody head of the Muirdris aloft for all to see and called defiantly to his faithful warriors and elders, ‘I have survived.’

They cheered long and loud to see Fearghus smile faintly. But delight in their chieftain’s victory and the return of his handsome countenance was short lived, for then and there he fell down dead and never spoke more.

Fearghus mac Léti, king of the Ulaid, faced his greatest fear and arose triumphant. Alas, in so doing he forfeited his life. Such was the price of atonement and a chieftain’s honour.

THE MERMAID AND THE MONK

Mermaids appear in folk stories all along the eastern and northern coast of Ulster, often in preference to the seal-folk and selkies of western shores of Ireland and Scotland. Sea-nymphs of whatever variety probably have a common and ancient origin.

The setting for this story is the island of Oendrium (Nendrum). It lies in what was once called Lough Cuan by the Irish but Strangr Fjörðr (Strangford Lough – meaning strong sea lough) by the Vikings. They favoured it as a safe anchorage and a rich foraging ground.

The late fifth-century disciple of St Patrick, himself later canonised as St Mochaoi, founded an abbey on the island. In memory of this it was renamed Inish Mochaoi and the name Oendrium referred to the monastic settlement (both anglicised as Mahee Island and Nendrum respectively). The island was abandoned as a religious site some time in the fifteenth century.

I have heard variations of this tale with different settings. The County Down version is, perhaps, most famously rendered in the poem The Mermaid of Mahee by John Vinycomb, MRIA, 1833–1928.

Long before St Mochaoi (Maw-hee) ever set foot on Oendrium (Nendrum), and for many years after, holy men were drawn to the place to meditate and pray. They endured harsh winds and wild waves, but at least the rich seas supplied a never-ending bounty of shellfish, and the many seabirds and geese provided eggs and meat in their turn.

The strong currents and high tides also allowed the monks to build a tide mill to grind wheat grown in the fertile soils of the island, from which they could make bread and beer. They had everything they needed to survive in sufficient comfort. If not for the unwelcome attentions of Viking raiders, it would have been a sort of paradise.

But there was one more troubling complication to living on an island in the middle of Strangford Lough. The monks had to share their watery world with a mermaid. If her name was known, it has long been forgotten, but, even through the dark mists of time, traces of her existence live on.

Local people feared her above all the creatures and dangers of the lough. Her voice was said to be as sweet as liquid honey and more captivating than any bird or bard. Fishermen dreaded the sound of her angelic singing and her beautiful harp playing. Once heard, a man was helpless to resist her call. Her hair was the colour of gold and her eyes like sparkling blue sapphires. From the waist up, she was goddess-like. Her skin was pale and unblemished. She was said to be so beautiful that even one glimpse rendered the onlooker a drooling, helpless sleepwalker. Below, she had the dazzling, powerful tail of a great sea creature that drove her through the water with such grace.

Families all around that coast lamented the loss of much-loved fathers, sons and brothers who had been lured into the dark waters of Strangford by the Mermaid of Mahee Island. Her appetite for men seemed to be insatiable. Her lovers were many but once seduced they were transformed into mermen and forevermore destined to live in caves beneath the cold waters as her captives.

As for the monks, they depended on their strength of faith to stand against the Mermaid of Mahee Island. Fortified by weeks and months and years of meditation and sacrifice, they were able to resist her terrible temptations. But she never failed or faltered in her labours to lure them away from their godly pursuits. She knew that sooner or later her endeavours would be rewarded, and she had all the time in the world.

Eventually, one young monk, weakened by doubt, abstinence and the austere routine of monastery life, heard the siren call of the Mermaid. To his unguarded ears her strangely beautiful singing and harp playing were so mesmerising and tempting that he was drawn to her like a salmon to its native river. He walked into her arms and into the sea never to be seen by his fellow monks again. Prayers were said for his soul, but nothing could be done now to save him. He had gone over to the otherworld.

Hundreds of years passed. There were many Viking raids into Strangford Lough and the timber-framed wattle and daub monastery on Mahee Island was razed to the ground and rebuilt many times over. Eventually, fortified stone works were built, including a round tower into which the monks could retreat in times of trouble. Life for the monks changed little over the centuries, however. They still had to gather and grow their food. They still had to study, pray, meditate, illuminate and endure.

One day, an old man came among the monks as they went about their daily tasks. He was bewildered and dressed in tattered garments the like of which no one had seen for many years. He could speak their language and he even understood the Latin Mass and prayers, but he was a stranger.

‘What has happened to this place?’ he asked. ‘Where is brother Mochaoi?’

‘Brother Mochaoi? He is dead and gone long centuries ago,’ said the monks. ‘Who are you? And from where have you come?’

‘I am a monk here,’ he said, ‘but I recognise not a single one of you.’

The old man told them the story of his fall from grace into the arms of the Mermaid of Mahee Island. The young monks laughed at his fantastical story, though some had heard the legend. The abbot was sent for, and he listened to the old monk’s story, pausing him often to ask questions about their patron Mochaoi and St Patrick when their names were mentioned.

‘Why did you return brother?’ asked the abbot.

‘I heard the Matins bell and was wakened as if from a dream. I thought a night away long enough and I returned to beg for forgiveness.’

The old man’s story was so strange and unbelievable, and yet the abbot could not explain his familiarity with the island, its history and environs, let alone his deep religious knowledge. As uneasy as he was to let the old man stay and tell his strange lurid stories to the young monks, the abbot felt somehow compelled.

‘You may live in a cell in the tower and ring the bell daily for services,’ he said. ‘Dream your dreams, but do not disturb our peace here or unsettle the brothers. For your absolution you must look to the Almighty.’

Among the haunted ruins of Nendrum monastery can still be heard the faint whispers of monks at their devotions. On calm summer evenings, and fainter still, is sometimes heard a plaintive singing. It mingles with the call of the curlew and all the little voices of the shore birds as they move up and down the lough in time with the tides.

County Antrim

THE CUSHENDALL HORSE DEALER

I first came across this story over forty years ago in Jack McBride’s delightful book, Traveller in the Glens (Appletree Press, 1979). J. McB said that it was told to him by a Glensman (no name was given) who claimed his grandfather was the main protagonist. I have long told a version developed from J. McB’s little sketch.

In this rendering, I have also taken the liberty of blending some additional material regarding a ‘charm’ central to the story. This extra scrap of folklore was gleaned from Michael J. Murphy’s book, Now You’re Talking (Blackstaff Press, 1975), and was originally collected on Rathlin Island. It seems to me to be so closely related to J. McB’s story that it could be a long-forgotten fragment of it. In any case, I include the extra detail here in the hope that it enriches the narrative.

More than 150 years ago, there was a prosperous horse dealer who lived in the Glens of Antrim. Once a year he sailed in a little schooner, of which he was part-owner, from Cushendun over to Campbeltown on the Mull of Kintyre. He was as well known as a canny horse dealer in Argyllshire as he was in his native Glens.

Up and down the length of the Mull of Kintyre, the dealer travelled in search of Highland ponies. For any that took his fancy he would offer the poor crofters as little as he could get away with. When he had gathered enough to fill the schooner, he would ferry them back across the North Channel. Then, after a wee bit of grooming and feeding he would sell them for a tidy profit at Cushendall horse fair.

One year, as usual, he was on the road, dealing as he went and gathering quite a herd of fine animals. One evening, near the end of his trip, he was approaching Campbeltown when a thick sea mist swept inland. The horse dealer was well used to this and the horse he was riding knew the way well and so he carried on. After a while, he came upon a small dwelling. ‘I don’t remember this wee place,’ he said to himself.

His curiosity aroused, the dealer approached the croft. The thatch was in need of repair and the walls could have done with a lick of fresh whitewash. ‘Just the sort of place that might be glad of a few shillings,’ the dealer thought to himself. When he went to the door, an old woman answered it. She was very small and stooped with age.

‘What do ye want?’ she asked, very sharply.

‘I’m looking for horses to buy,’ said the dealer, ‘but to tell you the truth I’m a bit lost.’

‘I’ve no horses for sale,’ snapped the wee woman and made to close the door.

‘Could ye spare a drop of tae then – for a weary traveller?’ asked the dealer.