8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: intimately Rooted Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

You went to your first Contact Improvisation (C.I.) class, or a friend invited you to the weekly jam, and you’re captivated. Or perhaps, you’ve been dancing and investigating for years. What’s next? What discoveries await you in your dance? In 1972, Steve Paxton convened a group of athletes and dancers to research the principles of Contact Improvisation. Since then the form has matured into a worldwide, collaborative experiment with no central control. Everyone who enters adds their findings and permutations to this inherently unfinished dance form. Dancing Deeper Still is a sourcebook of essays on Contact Improvisation, a philosophical treatise, and a handbook. This compilation of 30 years of writings is meant to accompany and support your investigation as you discover new pathways and dynamics in your dancing. It includes chapters on: · Contact Improvisation in performance· Boundaries and sexuality· Political activism· Dancing while aging· Expanded teaching research notes· Advanced skills Whether you are the improviser who savors the slow rivers of sensation…or who delights in spontaneous acrobatics…or any of the bountiful realms in between, this book was written for you. Your discoveries enrich the community-held body of knowledge in our ever-evolving form. I invite you to dance deeper still.Martin Keogh dances, teaches, and researches Contact Improvisation. His love for the dance has taken him to 31 countries across six continents. Keogh was named a Fulbright Senior Specialist for his contribution to the development of the form.Martin spent time in monasteries in Japan and Korea and was the director of the Empty Gate Zen Center in Berkeley, CA before he discovered the world of dance. He is the author of: As Much Time as it Takes and the anthology: Hope Beneath Our Feet: Restoring Our Place in the Natural World. He lives with his family by the Salish Sea in British Columbia. martinkeogh.com

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Dancing Deeper Still

The Practice of Contact Improvisation

Martin Keogh

Intimately Rooted Books

Terra Incognita

There are vast realms of consciousness still undreamed of

vast ranges of experience, like the humming of unseen harps,

we know nothing of, within us.

Oh when man has escaped from the barbed-wire entanglement

of his own ideas and his own mechanical devices

there is a marvelous rich world of contact and sheer fluid beauty

and fearless face-to-face awareness of now-naked life

and me, and you, and other men and women

and grapes, and ghouls, and ghosts and green moonlight

and ruddy-orange limbs stirring the limbo

of the unknown air, and eyes so soft

softer than the space between the stars,

and all things, and nothing, and being and not-being

alternately palpitant,

when at last we escape the barbed-wire enclosure

of Know Thyself, knowing we can never know,

we can but touch, and wonder, and ponder, and make our effort

and dangle in a last fastidious fine delight

as the fuchsia does, dangling her reckless drop

of purple after so much putting forth

and slow mounting marvel of a little tree.

– D.H. Lawrence

Dancing Deeper Still

The Practice of Contact Improvisation

Intimately Rooted Books

©2018 Martin Keogh. All rights reserved

ISBN-978-1-7752430-1-4 (Hardcover)

ISBN-978-1-7752430-4-5 (Paperback)

ISBN-978-1-7752430-3-8 (Ebook)

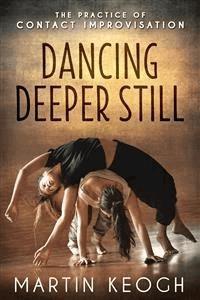

Cover design: Elizabeth Mackey

Front cover photo: Sören Wacker: sorenwacker.pixieset.com

Dancers: Rose Leighton and Jeanette Soria

Back cover dance photo: Thomas Häntzchel

Dancers: Martin Keogh and Rick Nodine

Back cover bio photo: Nadja Meister

Many essays in this book first appeared

in Contact Quarterly, Proximity, and Yes! Magazine

Dancing Deeper Still: Version X (2018)

Former Editions:

The Earth is Breathing You (2001)

The Art of Waiting (2003)

Get in touch:

Also by Martin Keogh

Hope Beneath Our Feet

Restoring Our Place in the Natural World

As Much Time as it Takes

Handbook for the Bereaved, their Family and Friends

Etched in Your Brain Name Games

How To Guide for Teachers, Group Facilitators

and Insightful Leaders Everywhere

Book information, videos, and workshop itinerary:

martinkeogh.com

This book is dedicated to

Dylan Keogh

Contents

Foreword

Also by Martin Keogh

Introduction

Part I

1. The Time of Your Life

2. The Earth is Breathing You

3. 101 Ways to Say No to Contact Improvisation

4. Musings on Being a Touring Contact Artist

5. Jalapeño Peppers in the Blood

6. Throwing Salt (with Gretchen Spiro)

7. Dancing Under Different Constellations

8. Taking a Stand (with Keith Hennessy)

9. The 38 Gifts of Contact Improvisation

10. Cat’s Pause and Bare Feat

11. Skills of ‘Labbing’

12. Dancing Deeper Still

13. Moments of Rapture

14. Old Growth

II. Teaching Research Notes

15. Introduction

16. Who can Teach Contact Improvisation?

17. Initial Contact

18. Holding Space

19. Finding Material

20. Sequencing (with Brenton Cheng)

21. Teaching Tools

22. Stumbled Upon Pearls

23. Language

24. Giving Feedback

25. To the Heart of Feedback

26. Nuts and Bolts

27. Embers in the Heart

Acknowledgments

Introduction

For decades I dreamt of becoming an author. I imagined myself in a sparsely furnished cabin with a well-tended fire, writing for hours each day. Yet, that dream lacked one important detail. Whenever I sat down to write I became flummoxed in my hunt for subject matter.

Then 9/11 came crashing into our lives. Within a week of that event I realized I did not need to go on some wild pursuit; my subject would be Contact Improvisation (C.I.), the dance form I spent so many decades teaching and performing. In between touring and parenting and partnering, I began to write.

The San Francisco, Bay Area has long had a thriving community of Contact dancers. My decades there provided me with a wealth of learning. We danced together at weekly Contact jams, at residential dancing events, and at rehearsals and 'labs' to research the form. We also danced in city parks, in the downtown financial district, and at 'dune diving' parties at Point Reyes National Seashore. During one trip to the zoo we marked off an area of grass with rope, put up an official-looking sign that proclaimed, "New at the Zoo," and a group of us had a round robin of dances in the enclosure. People stopped and read the sign. Some looked at us quizzically. A few joined in.

After a day of dancing on Limantour Beach, a group sat around a campfire listening to the waves breaking on the shore. A few of us were part of Touchdown Dance, an organization that introduces Contact Improvisation to the blind. As we sat surrounded by darkness, watching the dance of flames and the shimmering coals, one person asked, "How would you describe fire to a blind person?" Our attempts to create a verbal picture that gave the sense of fire were feeble next to the crackling and prancing of the flames that warmed us. How do you describe something as varied and changeable as fire without putting a person's hand in it? In that moment I realized why it's hard to define Contact Improvisation. Like fire, it's in motion, it's mercurial. The essays in this book are my attempt to describe the crackle and blaze of our dancing.

One of the more challenging aspects of researching Contact Improvisation, because this extemporaneous form calls for an ongoing inquiry, is the constant admission that I don't have it all figured out... and I never will. These essays catch me at moments in the investigation. They reflect questions and answers that illuminate an instant rather than a doctrine. In writing, I find the same challenge as when I dance or teach, to enter a sense of improvisational inquiry rather than a set of dogmatic rules. Every person has their own individual doorways into the dance. These are some of my doorways - what I've experienced and learned after almost forty years of engaging this form as a teacher and performer.

In a large dance complex in Oakland, California I saw two modern dance teachers peering at a Contact class through a small window in the door to the studio. I overheard one say to the other, "I can't believe it, they're sitting and talking again."

What she found so perplexing is something I cherish about the form. This dance puts a priority on our ability to be lucid in the moment, and our capacity to articulate our experience and research to others. This has helped my writing.

I enter the writing in the same way I warm up for dancing. I'm not climbing a mountain; it's not some Herculean task. I don't need to rise to the occasion. I descend into that place in myself where I am already prepared to dance, where the language is already present.

Language is important. How do we track down those metaphors that give a visceral feeling for what we do when we dance? My job is to tame a few of the many thoughts. To entice, coax, and persuade images to sit on the page.

The hardest images to catch are the nocturnal ones, with their reflective eyes that can only be glimpsed at night. How does one write about the shadow side of the dance, the ephemeral qualities of the form, the dance of boundaries and emotion, the confluence with the spiritual, the rapture? For those images to be seen in all their feral wonder, one has to enter without a light and magnify other senses to perceive what is present.

I'm fortunate to have a passion for both dancing and language. Written during four decades of rapport and grappling, of discord and harmony, this book is my love letter to the dance. What follows is a series of essays, collaborative writings, and teaching research notes. You can read this book from the beginning or you can thumb through the pages and start reading when whim moves you.

I am grateful to Steve Paxton for his initial outlandish idea to gather a group of people to investigate his ideas that became C.I. My appreciation goes to the originators for their foresight to not codify the dance and become the "C.I. police." This allowed Contact Improvisation to grow organically so it could mature into something that no one could have intended or even imagined.

I'm thankful for the generosity of all my teachers, and to Nancy Stark Smith for her commitment to language and her decades of cultivating the form through the Contact Quarterly magazine. Most of all, thanks to my students, collaborators, and dance partners that continue to make life so rich.

I also dedicate this book to you, the reader. Parts were written in San Miguel de Allende in the high desert in Mexico. Sitting outside at a cast iron table, surrounded by purple and crimson bougainvillea blossoms, visiting hummingbirds and the sounds of bells and chickens. The colors of the sidewalk flagstones after a rain, the smell of roasted poblano chilies filled with cheese, the cooing of doves feed my desire to colorfully bring this dance into language. And parts of this book were written in the temperate rain forest by the Salish Sea in the company of seals, river otters and orcas. They swim through these pages. In reading these essays I hope that you receive some of the pleasure I experienced in writing them.

Part I

1

The Time of Your Life

Recently I returned to the Southeast to teach a two-weekend Contact Improvisation workshop in Washington, D.C. and Richmond, Virginia. I’ve taught in these communities several times before and didn’t want to repeat my tried-and-true material. To challenge myself and the students, I created a theme I needed to grow into. The workshop was titled “The Time of Your Life”. This was the description:

In this 4-day workshop we will use the learning of Contact Improvisation to investigate our relationship with time. With games, some sweat, and the unique physicality of the contact form, we will ask:

These questions will arise as we master more of the skills and thrills of the Contact form. Special emphasis on surprising ourselves in flight and extended follow-through.

I was interested to delve into experiencing time passing in a way that was kinesthetic rather than conceptual. My goal was to keep our explorations experiential and based in sensation. I wanted to see, when we dilated our attention to notice the details of each moment, if time would slow down.

I’ve always been interested in time. I spent six formative years growing up in Mexico and I’ve lived there twice as an adult. Time in Mexico is different; it’s slower, as if moving in a long unhurried arc. In the United States, particularly in the north, it seems there is rarely enough time. There is a sense of people starving for time—in a rush, too much to do, drawn thin, overwhelmed, tense. Like being at a high altitude, people are gasping for time. In a land prosperous with belongings and stimulation, we are paupers when it comes to time.

I often start my classes by saying, “There is no rush, there is nowhere to get to, there is nothing that has to be done. Today, we have plenty of time.” This is frequently followed by sighs and shoulders dropping a centimeter or two. We tend to brace against time, trying to pack so much into it that simply hearing that there is enough for the time being lets us begin to relax.

I used to complain in class that I wished I had more time. Then I realized that I was falling victim to wanting too much. Now my mantra is: do less. Whether I have a seven-hour workshop or a fifty-minute class, I have plenty of time. I often take down the clocks in the dance studio so that we can get out of clock time and enter body time.

In The Time of Your Life workshop, I began by asking everyone how they relate to the idea that we have seven hours together. Do you see this time span as a straight line or a curved line? How does it feel to you? Do you picture time? Or feel it kinesthetically? Does time have texture for you? Is it like velvet, a water slide, itchy weeds, or is it rough like sandpaper?

We then did an awareness exercise that is effective for quieting the mind and becoming present. We wrap one hand around the thumb of the other hand. Letting the hands rest in the lap, we feel for the pulse in the thumb. When we find the pulse, we count backwards from ten to one on the beats of the pulse, and then feel a few more beats. We then change to the other thumb. Going back and forth we do every finger down to the pinkies.

I have found that this simple awareness of an interior rhythm allows something at the core to settle and the mind to become quieter. It’s also a wonderful way to get to sleep at night when the mind-grinches want to keep you awake.

Most people “see” time as moving in a direction. In front of us is the future; behind us is the past. We hear phrases like “That is behind us now” and “We will see what lies ahead.” I feel that this commonly held “view” of time has an effect on our dancing. It makes our movement more linear and symmetrical and less spherical and multifaceted.

I suggested to the class the image that time comes at us from every direction, from the entire sphere all at once, and disappears into the past inside us. Time surrounds us—we are consumers of time; we ingest it.

We used this image of time coming from every direction as a way to meditate on the threshold inside us, where time crosses over from the future, from the outside, to the past, on the inside. We “sit” in the cusp of time. This slight change in our view of time from linear to spherical had the effect of changing our perception of time from visual to kinesthetic. As we meditated on the passing of time, we played with putting the threshold where time passes into the past in the brain, in the heart, in the belly, in the groin, and at the skin. We made ourselves porous to time, feeling it as it passed into us.

From this place of awareness, of feeling time in motion, we began to move our bodies. We let the velocity of time move us. We filled our sails with time, looking for the pace where the movement was effortless.

When a person shouts into a canyon, each gorge has its own pitch at which an echo comes back the clearest. In the same way, each person has a rhythm in which they can move with lucidity and clarity. They do not will their movement along but rather allow velocity to move them. People can move for a long time once they find that rhythm. So, for a half hour, an hour, in the class, we moved, riding the brim of time.

This work evolved into partnering. With the complexities of a relationship that arises from working with a partner—expectations and judgments and reactions—it became difficult to keep our awareness on the passage of time. At first, we had to slow down. It took practice to quiet down enough internally to achieve a state where we could kinesthetically experience the dance with our partner as the embodiment of time passing.

At this point, the workshop turned a corner and the focus became how to stay in that quiet internal place while dancing in a variety of dynamics.

The Art of Waiting

I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope

for hope would be hope for the wrong thing;

Wait without love

for love would be love of the wrong thing;

There is yet faith

but the faith and the love and the hope

are all in the waiting.

Wait without thought,

for you are not ready for thought:

So the darkness shall be the light,

and in the stillness the dancing.

—T. S. Eliot

Working with time led us down an unexpected back road into the act of waiting. I have experienced that the people who bring the broadest palette of colors to the dance bring a quiet thread at the core of their movement, a stillness. There is a sense that amidst the velocity and action, amidst the hurricane of activity, there is a quiet eye. I get the sense that there is a place in these dancers that is in the act of waiting.

The dictionary definition of “waiting” reads, in part: “To be available or in readiness, to look forward eagerly, to stay or rest in expectation, to attend upon or escort, esp. as a sign of respect, to soar over ground until prey appears. Etymology: Old high German wachton: to be wide awake.”

I relate to waiting as being “wide awake” and “in readiness.” The idea of “soar[ing] over ground until prey appears” also pleases my imagination. The act of waiting is the act of soaring, in readiness, eyes wide open.

I’ve been looking for that quiet thread at the core for a long time. What seems like lifetimes ago, when I was in my early twenties, I lived for years at Zen Centers and spent time visiting monasteries in the Far East. This included a daily meditation practice and monthly retreats. What I found was that my mind loves to move and is not fond of sitting still.

When I discovered Contact Improvisation, it felt like I had walked into a house and knew where the furniture was—I felt like I was home. I resigned as director of the Empty Gate Zen Center in Berkeley, gave up my robes and bowls, and committed to a life of dancing. My constitution found it easier to become quiet while in motion than while trying to keep still with my butt propped up on a cushion.

When I left the Zen Center, I wanted to continue a regular practice. Knowing that movement was easier for me, I decided to do yoga. But I found a resistance to the long routine and could never keep it up. After a decade of off-again/on-again practice, I asked myself, why am I beating myself up about this? How can I find the pathway of ease? I played with different formats until I found that I could do six minutes of yoga each morning.

Six minutes. It works. I do it joyously. It feels like I could still do more, and the next day I’m happy to return. And over the decades, those six minutes kept doubling. By the time I’m 80 I expect to have a two-hour joyful practice daily.

From this research into what works to make a busy mind like mine quieter, I’ve found other methods like the finger meditation described earlier. Most of these simple meditations ground a person somewhere in the body and the senses:

listening to the farthest sound / listening to the sound right in the earsbreathing through the mouth and nose simultaneouslya slow soft self-caressthe “small dance” of standingawareness of both the transition between the exhale and the inhale, and the transition between the inhale and the exhaleAnother one of my favorites I learned from the Vipassana meditation teacher, Jack Kornfield—the raisin meditation. Take a raisin and keep it in your hand. Feel the weight of it. With a finger, feel the texture and density of the skin and pulp. Put it to your nose and become aware of the topography of the raisin’s scent. Look into the valleys and peaks, the highlights and dark crevasses. Then put it in your mouth, close your eyes, and take a couple of minutes to get the full experience of eating a single raisin. Notice the trajectory of the flavor as it bursts forth, the flood of saliva, and the way the body’s chemistry changes the flavor. Notice the aftertaste and the echoes of the aftertaste.

Doing this awareness exercise as a class warm-up opens up the body and faculties for C.I. As the senses awaken and open, the joints lubricate, creating a willingness to stay engaged in sensation as we go into movement.

We started the second afternoon of the workshop with the raisins. Continuing the awareness into the aftertaste is important in what it teaches us about waiting. When I dance with someone who has the lucid quality of waiting, I notice that while in motion they tend to broadcast where they have just been. They are still tasting or hearing the echo of what was. As their dance partner, I get the opportunity to relate to a range of possibilities—where the movement appears to be going, where it is in the moment, or where it just was.

To paint a picture of this: Imagine that you are dancing with a partner and you are both on your feet and in physical contact. Your partner begins to fold to the floor, softly creasing at the ankles, knees, and pelvis. But as your partner folds down, he leaves a hand up at your chest level. At this point, he might continue to the floor or, by centering in the hand left behind, spiral back up to standing. As his partner, you have a choice of relating to the destination of the floor, to the dropping motion itself, or to the hand that has stayed up in the air at your chest. By leaving something behind, his movement opens up your choices as well as his own. In each moment, there is a sense of relaxation in the myriad of choices. And in that profusion of options, in that generosity of possibilities, the cusp of the present gets wider. The moment becomes more alive in all that it is offering.

When myriad possibilities appear in each moment, the opportunities for self-criticism go down. You are less likely to think, “Oh, I missed that one,” because there are many more than “one” to choose from. The pathway you end up taking is simply what you are contributing to the dance, and you’re less caught up in ideas of right and wrong.

For years I have wondered how I, how a person, can increase their capacity to stay in this quiet core. What I increasingly find is the need to let go of willful control, to drop the reins, to let the animal brain and body have a stronger voice. There is an inner dictator that demands resolution, a resolution that is fixed and unchanging. He wants a single picture of the river rather than letting the river flow. (My inner dictator also wants the classes I teach to be entertaining.) How do we increase our capacity to live in the unresolved?

James Hillman talks about this state when he writes:

But reaping these rewards requires learning to accept a self that remains ambiguous no matter how closely it is scrutinized. Fluid, active, filled with unresolvable contradictions, it is the nature of the self to remain beyond the ego’s willful demand for a logically consistent system.

It’s like hitchhiking by the side of the road. You don’t know if you are going to get a ride in the next minute or in the next three days. It’s throwing yourself into your destiny—part is choice and part is surrender.

In the second weekend of the workshop, we danced with the idea of leaving something behind by working with the idea of follow-through—letting each movement, each moment of the dance be the seed of the next. We attempted to calm our conscious and unconscious willfulness by allowing each instant to follow through rather than throwing in new impulses.

We also did exercises to build our capacity for staying in disorientation by continuing to follow through rather than re-center—even when we were off balance, up high, or in a moment of exhilaration. Especially in these moments, we tried to leave something behind, stay quiet at the core, continue with a sense of soaring over the ground, looking for prey—waiting.

During these two weekends, did time slow down? Had our focused attention given us more day? The spherical quality of our time did make the present junctures seem wider, like there was more choice, more experience packed into each moment. But at the end of each day, we were all surprised that our time was up so soon.

2

The Earth is Breathing You

Why we practice to center and ground

Imagine gazing up at a 30-floor building that is under construction. The structure towers 300 feet over you and is nothing but girders and steel beams. You take the freight elevator to the top floor and the doors slide open. Between you and your destination juts a 10-foot-long steel girder and a mild breeze. You look below through 300 feet of open space to the ground. People look like slow moving ants.

What do you do to prepare yourself to walk out on that beam? What do you do physically and emotionally to take the first step? How do you find a connection, even from way up here, to the ground?

This preparation is called centering and grounding. It’s about coming home to yourself and your relationship with the constant influence of gravity. These skills are an essential step for developing responsiveness as a dancer. Until we know that firmness in our own two feet, it’s difficult to feel confident in the rich world of being off balance and the unpredictability of shared centers with others.

Training for this moment is found in many disciplines. Some practices imagine the body’s center about 2-3 inches below the navel, in the abdomen. If you dissect a body you won’t find a gland or bone or star sapphire to mark the spot. But in relationship to the ground, the entire pelvic girdle can become a source of strength and connection that supports our movement.

A strong center can hold its ground. It is stable, rooted, can take a position of responsibility, face life squarely, be firm in its footing. It is content, without the need to go out and find justification for itself. It can wear robes and jewels and the crown of royalty – it can say, “Here I am!”

Learning to center and ground comes from a frequent returning to the core. One has to return under varying circumstances to become familiar with this place. In dance class, we start with controlled situations – then work with staying centered in more uncontrolled and chaotic conditions.

Imagery is an effective tool for this practice. We imagine attaching our pelvic girdle to the ground with a tap root, connecting to the middle of the turning earth, or to an artesian spring streaming up through our core. We might see ourselves as a granite mountain with crags and ledges, or we might stand and feel the earth is breathing us. As we sense the tug of gravity on our bodies it’s helpful to imagine that at the same time gravity is pulling us from below, it is also pushing us from above. This puts us kinesthetically in the center, giving us a sense of being supported and held between two forces rather than one.

A common structure Contact Improvisation teachers use is the feather/boulder exercise. Half the class chooses to imagine that they are a feather or a boulder. The other half walks around and tries to pick these people up. As a boulder, the image leads a person to drop their center and move it away from their partner, making them heavier. As a feather, the person raises their center and puts it close to their partner’s core, which makes them lighter. Each teaches us something about the other and both teach us the power of imagery.

After working with images and exercises for centering and grounding I like to test our abilities in increasingly challenging situations. One of my favorites, not only for what it teaches us about the power that comes from our centers, but also for the energy it generates in class, is the Two Against One exercise.

Two people stand tightly side by side. They cross their arms firmly against their rib cages. A third person, also with their arms crossed, pushes against the fronts of the duo. The job of the duo is to slowly push the single person backwards so the single person can feel the edge of their strength. The job of the single person is to attempt to push the two people backwards. The lesson is about finding ground and center and pushing with all the strength one can muster. Grunting and yelling are encouraged. (The word “grunt” comes from the same root as the words “ground” and “groin.”)