Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

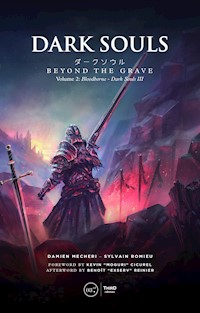

- Herausgeber: Third Editions

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Serie: Dark Souls. Beyond the Grave

- Sprache: Englisch

Story of a saga video games...

If the Dark Souls series managed to seduce players and journalists, it was mainly by word of mouth. It was such a great success that Dark Souls 2 was named “Game of the Year” 2014 by the vast majority of gaming magazines and websites. To date, this saga is one of the most important in the gaming industry. The odd thing is that these games are well known for their difficulty and their cryptic universe. This publication narrates the epic success story, but also describes its gameplay mechanics and its specific lore across more than 300 pages. Characters, plots and the scenario of the three Souls (Demon's Souls, Dark Souls and Dark Souls II) are deciphered by Damien Mecheri and Sylvain Romieu, who spent a long year studying these dense and enigmatic games down to the smallest detail.

The serie Dark Souls and her spiritual father Demon's Souls will not have secrets for you anymore!

EXTRACT

"In May 2014, Hidetaka Miyazaki succeeded Naotoshi Zin as president of FromSoftware, after the studio was purchased by Kadokawa Shoten. This was a highly significant promotion for the person who had led the company’s most successful project, Dark Souls. And yet, he did not lose from view what had attracted him to the field: an insatiable creative drive. In spite of his new status within the studio, one of the conditions he requested and was granted was to remain creative director of his new project: Bloodborne. This allowed him to successfully design this spiritual successor to the first Souls game, while also assuming his new responsibilities. Given his drive to work and create, it is not surprising how quickly Miyazaki moved up through the ranks."

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Passionate about films and video games, Damien Mecheri joined the writers team of Gameplay RPG in 2004, writing several articles for the second special edition on the Final Fantasy saga. He continued his work with the team in another publication called Background, before continuing the online adventure in 2008 with the site Gameweb.fr. Since 2011, he has come aboard Third Éditions with Mehdi El Kanafi and Nicolas Courcier, the publisher’s two founders. Damien is also the author of the book Video Game Music: a History of Gaming Music. For Third Éditions, he is actively working on the “Level Up” and “Année jeu vidéo” collections. He has also written or co-written several works from the same publisher: The Legend of Final Fantasy X, Welcome to Silent Hill: a journey into Hell, The Works of Fumito Ueda: a Different Perspective on Video Games and, of course, the first volume of Dark Souls: Beyond the Grave.

Curious by nature, a dreamer against the grain and a chronic ranter, Sylvain Romieu is also a passionate traveler of the real and the unreal, the world and the virtual universes, always in search of enriching discoveries and varied cultures. A developer by trade, he took up his modest pen several years ago to study the characteristics and richness of the marvelously creative world of video games. He writes for a French video game site called Chroniques-Ludiques, particularly on the topic of RPGs, his preferred genre.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 562

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dark Sou/s. Beyond the Graveby Damien Mecheri and Sylvain Romieu Edited by Third Editions 32 rue d’Alsace-Lorraine, 31000 TOULOUSE [email protected]

Follow us: @Third_Editions - Facebook.com/ThirdEditions

All rights reserved. Any reproduction or transmission, even partial, in any form, is forbidden without the written consent of the copyright holder.

Copy or reproduction, regardless of the process used, constitutes an infringement of copyright and is subject to penalties set out in law no. 57-298 of March 11, 1957 regarding copyright protection.

The Third Editions logo is a registered trademark of Third Editions, registered in France and in other countries.

Publishing: Nicolas Courcier and Mehdi El Kanafi Text: Damien Mecheri and Sylvain Romieu Editing: Thomas Savary, Christophe Delpierre and Nathan R. Illustrations: Alexandre Dainche Layout: Julie Gantois Cover Creation: Benjamin Brard Classic Cover: Jan-Philipp Eckert “Collector” cover: Hélène Builly Translated from French by: Elise Kruidenier (ITC Traductions)

This book aims to provide information and pay homage to the great Dark Souls videogame series. In this unique collection, the authors retrace a chapter in the history of the Dark Souls video games, by identifying the inspiration, background and content of this series through original reflection and analysis.

Dark Souls is a registered trademark of Bandai Namco. All rights reserved.

The classic cover art is inspired by artwork from games in the Dark Souls series.

The collector cover art is inspired by the painting Magdalena Bay by François-Auguste Briard.

English edition, copyright 2017, Third Éditions.

All rights reserved.

ISBN 979-10-94723-57-9

To Hugo,born as this book was being created.

PREFACES

ONE thing harder than playing Dark Souls is understanding its story. The sheer amount of lore in this game is overwhelming, with the most intricate details hidden within hundreds of item descriptions, dialogue, environmental dues and the gameplay. Harder even still is telling that story. Often, I find my narrative jumping between characters, timelines and games, and I used to worry that I’d lose readers in the process. Only after years of practice did I become confident in my ability to bring viewers along with me on one of these tales.

Upon opening Dark Souls: Beyond the Grave, I flipped straight to Chapter Three: Universe, spanning pages 89-217. I knew this section would be the ultimate test of the authors’ skills, for it is difficult to write emotively about characters whose motivations are a mystery. It’s difficult to know where to start when the reader really needs the full picture in order to understand.

Even though I had unfairly skipped 93 pages, I was met with a patient, wise explanation of the way the story works: “Everything must be discovered along the way, and sometimes even imagined. This can become frustrating over time–particularly for more logical players. Every bit of information collected is like a small piece of an immense narrative puzzle. However, even after several complete games, many pieces are still missing. Players can use their imagination to set out again in search of dues within the game’s decor, character equipment or in other previously neglected spaces. In spite of the years that have passed since the first Souls game, it’s hardly surprising that the community of players still buzzes with excitement. People discover new elements every day, adding their stones to the vast cosmogonie edifice. Between new ambiguous information and eccentric theories, the Souls universe has never stopped breathing.”

Dark Souls: Beyond the Grave shows the story respect. The telling of the lore is emotive enough to keep you entertained, but never strays too far from what is known for certain. The authors are careful to acknowledge their dives into the unknown, and deferential to attention span, stopping just shy of the ever-present threat of “too much information.”

Take, for example, this quote that precedes the chapter on the beginning of Dark Souls: “The Flame, true embodiment of the Age of Fire, would one day begin to flicker. Was this a terrible curse besetting the kingdom, or simply the passage of time? Who can say? What is certain is that the Flame was on the brink of going out.”

The authors then writes: “It is at this moment that the story of Dark Souls begins.” For you, reader of this Preface, I believe the same holds true.

VaatiVidya, One of the world’s greatest specialists of Dark Souls’ lore.

GANDHI said that any single verse selected at random from the Bhagavad Gita would brighten the darkest moments of his life.

Modern game designers could say the same thing regarding the Souls series, and Dark Souls in particular: every aspect, even anecdotal, is a major lesson, a wellspring of inspiration that, like many of the dungeons in this awe-inspiring game, seems to have no end.

As with many great discoveries, the magic of the Souls series does not result from a perfectly formed ensemble, but rather from the repeated convergence of happy accidents. In Dark Souls: Design Works (2013) Miyazaki admits that the idea of a world revolving around light and dark came late in the production process. The initial project was inspired by the importance of water, and the Firelink Shrine sunken chapel is a vestige of that first concept.

Game designers can find it unsettling and demoralizing when the foundations of a production are thus shifted, but the teams remained focused on the essentials of what makes a truly good game (level design, gameplay, atmosphere and the desire to make a new kind of game) in order to create this beacon that now guides us all, if indeed it is possible for a beacon to shine with darkness and melancholy.

Borderlands and Halo both mirror Dark Souls in some ways, but there are a number of independent games that borrow some or all of the series’ mechanics and reference points, as if the creators were cursed, and were seeing to convey through their production a faint echo of what possessed them.

At a master class in Paris, Greg Zeschuk, the mind behind Baldur’s Gate, Knights of the Old Republic and Mass Effect, was asked if he still plays games. He answered that he wasn’t really drawn to any games really, except maybe Dark Souls, the last game to really “blow [his] mind.” This statement echoes the reactions of most game designers: the Souls games leave an impression, and for a precise reason. A Souls game cannot be completed using thousands of different strategies. Players must know it by heart. By the time you emerge victorious, you’ll be more intimately familiar with Sen’s Fortress than the inside of your own family home.

We live in an age when most games are consumed like airport novels, read in passing and quickly forgotten. The Souls games change our mode of consumption, or rather return us to a time when video games were a rare thing, and a new game was an event or a celebration. If the Souls games were novels, we would be glued to them–each word could be a trap or a revelation–and closing the book before its end would represent a veritable defeat.

As our current-day marketing apparatus works to promote games accessible to all, the Souls series attracts people to their brutality, requiring cooperation between players.

Many incredibly “demanding” games–manic shooters, for instance–reward overcoming difficulty by supplying an even greater challenge. This is somewhat the case in Souls as well, but the ever-more-difficult stages also transport you to increasingly “mythical” locales, as if the game were grudgingly acknowledging your progress, because it is at once your enemy, your victory and your apotheosis.

The greatest quality of Dark Souls in my opinion is its relationship with learning. The game is a series of pain-based tutorials punctuated by bosses who serve as our examiners. A bit like disciples of Mr. Miyagi, we learn in spite of ourselves, and surprise ourselves as we grow stronger. In Souls, it’s the player who levels up, not the character. Sen’s Fortress is a striking example: up to this point, you may have been defeating enemies using tested positioning techniques and your shield, but the serpent men force you to immediately find the best lasting strategy: skirting around them to strike them in the back. At the end of the fortress, a forty-meter tall Iron Golem awaits, and you must strike him from behind, even though slipping through those colossal legs is quite the formidable task.

At the end of this long progression of learning and trials cornes the final boss, who requires you to deploy your best strategies. We are left to wonder, “Now that I’ve spent the whole game preparing and have succeeded, what am I really prepared for?” At the mountain’s summit, we begin wishing that the climb was not over. The Souls’ player motto is even The true Dark Souls starts here!

Another fundamental advance made by the Souls games is their multi-player component. Many games today still distinguish between single- and multi-player. In Souls, everything coexists, both from a technical standpoint as well as in the story’s background: every piece is like a story told by a different person, as is the case in true myth-telling. Players glide through your game like phantoms; they are there to complicate matters or to save you, and their hints transcend the language barrier through a system of pre-written messages. Their messages often warn you of dangers along your path, and in turn, you will pass along messages to others in a long, silent chain.

I have worked on several projects with illustrator Quentin Vijoux, a passionate fan of open world gameplay. He has his own “Vijoux criterion” for evaluating games. For a game to be high quality, he believes that if you can see a game element in the distance (such as a mountain, a tower, a pit of lava), you should be able to go to it, and once there, you should be able to view your initial location. This is a bit complicated, but it determines whether the universe is coherent, dense, and even meaningful from several perspectives. Dark Souls is head and shoulders above anyone else in this field. How could you guess that the abyss you see in the beginning will be the site of your future torments? How could you imagine that the lava you had trouble avoiding at the base of the world-tree would one day be your source of light through windows in far-off catacombs? Everything has meaning, everything is visually connected, and everything appears real. It provides a unique sense of immersion, in view of the natural complexity of this type of game.

With its forgotten gods, a quest for the Grail, and its phantoms, the Souls adventure is less fantastic or even heroic than it is mythic. While the heroes are destined to triumph, the universe of Souls draws just as much from tragedy. The forgotten or deposed gods dominate an abandoned world, haunted by these divinities’ giant servants and degenerate troops; here, man’s eternal quest for immortality appears more as a scourge, as all aspire to death. The fire within us must be quenched and the circle must be broken. The player is charged with a unique mission–that of destabilizing the cosmic forces, which is presented as a necessity to bring on a new era.

With the exception of the introductory clip, which can be skipped without impacting a player’s general understanding, the Souls story is not forced upon us through long, obligatory dialogues. Even if we take note of each of the game’s minute details, the story will not be perfectly clear; it instead sparks debates between us and our fellow players. Dark Souls demonstrates that the story is secondary to its telling, and maybe even, ideally, secondary to the pleasure of playing (and I say that as a professional creator of stories!). The Souls games do not explore the thread of a simple adventure, but rather a myth. No one knows exactly when Odysseus left and returned, or the exact path he took, but we know that he met sirens and cyclopes, magicians and terrifying monsters along the way. In Souls, you will embark on a quest of light or shadow, and you will meet with giant knights, sinister harpies and a princess with the tail of a dragon.

Souls plays on what Kubrick termed “the dark side of the imagination”: the story becomes one’s own, and transforms into a mystical symbiosis of the game itself and what the player brings to it. Rigid, canonical games such as those adapted to several media have just one story, one single game for players, and are often intended to be played in an optimum way (the so-called “optional objectives”). One can say that there are as many Souls games as there are players–everyone paints the murky dungeons with the unique hues of their imagination.

This focus on the dark side of the imagination and fascinating strangeness is very intentional: many game designers depersonalize enemies, for instance by giving them generic names to give them as little lore1 as possible (according to documents available on the subject, in any case).

The Souls are haunting games, as if they were playing you rather than you playing them. After finishing my first Dark Souls, it haunted my dreams for over two weeks. And no seasoned player can visit Chambord Castle in France without having the strange feeling of being right at home in the place. As in any good game, the Souls games require “extra-game” time: it is often when the console is turned off that you find solutions, after calmly turning the obstacle around in your head for a while.

With its mythical dimension, the Souls series revives a genre that has become uncommon in modern culture: tragedy. You die–it is fatal. But even if after your countless deaths you reach the end, you still have a gnawing feeling that nothing very joyous awaits you. Moreover, in the three Souls, the final boss is not simply the ultimate trial: the boss is a farewell, a mutual swan song, and in place of intense choral music, this ultimate dance of death is accompanied by soft and melancholic music.

Today, it is difficult to judge the influence of the Souls games, and particularly the first Dark Souls, because we are still too close to its cataclysmic arrival within the creative universe. Out There, my own game which justifies my writing of this work’s preface, clearly echoes the Souls games in its use of relentlessly brutal mechanics, the start-over in case of failure, and the environmental storytelling developed in the FromSoftware games. However, it is quite likely that for a long time, many games will simply be variations on the numerous revolutionary advances made by the Souls series.

FibreTigre, co-creator of Out There, author of interactive fictions

1 The story and plot taking place in the game world (Ed.).

SOULS INTRODUCTION

The Aura of the Series

Stepping into the Souls universe is a trial in itself. These games have a reputation for being demanding and mercilessly difficult. The series’ success is rooted in this challenge: Demon’s Souls emerged from obscurity primarily due to word of mouth that emphasized the daunting and anachronistic challenge posed by the game. However, this quality is a double-edged sword: it draws seasoned players, eager for the experience lost in the proliferation of player-friendly games, but it discourages those who fear they cannot overcome the difficulty.

This feeling of fear is strong when you tackle one of the Souls, and it persists throughout the game. It is the game’s lifeblood. The series’ episodes1 provide no easy rewards for the impatient, the reckless, or those who do not invest a minimum in the adventure. The largely incomplete tutorial is only meant to provide the foundation necessary to start out and defeat the first enemies. Players must discover the rest for themselves. They are released into the wild, so to speak, into a hostile environment where everything must be learned, explored and assimilated.

This abrupt and rudimentary aspect is the first impression, and it may put off players doubtful of their abilities. However, although the series’ reputation was forged on its difficulty and rich detail, this was also behind many misunderstandings. Through marketing hype and biased word of mouth, the arduous challenge posed by the Souls games eventually superseded all of the games’ other qualities. Worse still, the difficulty was seen as an end in itself, rather than an opportunity to have a certain type of experience, associated with particular emotions or sensations. The series’ creator, Hidetaka Miyazaki, has addressed this on many occasions. From the beginning, he has maintained that the game’s difficulty is only a means by which players can experience intense exaltation after overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Above all, he has always taken pride in the fact that almost anyone can conquer his games: the key to success does not lie in the player’s agility or virtuosity with the controls, but rather in their sense of observation, strategy and self-control.

As long as they play their part and fully immerse themselves, any player can embark on the Souls adventure. The difficulty should not be seen as discouraging, but rather as one part of the game’s experience, conducive to strong sensations. Deaths are frequent, yes, but never prohibitive. Here, death is not a “game over”: it is integral to progression. To die means to learn: it represents a cycle of renewed attempts until players fully assimilate the game’s mechanics, environment, enemy placement and boss approaches. Death in the Souls series should not frighten or discourage. This is why the series’ reputation did as much harm as it did good. When you focus too much on one specific element, and a potentially frustrating one at that, the overall experience is lost from view.

It is also interesting to note that there are a number of different ways to experience the adventure. The Souls games offer such a variety of approaches that they reveal a good deal about the players themselves. Most fascinating of all, even those who have played, or even finished, one of these games, have likely missed many of the game’s details. The inexhaustible richness of Souls is only accessible to the curious and the observant, and this is what makes the games so demanding, more than their difficulty, which really is just a means to an end.

One could almost say that there are as many different Souls games as there are players. Some will focus solely on mastering the game’s mechanics, or searching for rare objects and equipment, while others will revel in the increased difficulty with each New Game +, or the possibilities offered by the online system. Others still will be bewitched by the dank, fascinating ambiance of the different locations. Then, some players will perform a veritable investigation to understand the challenges posed by the universe and the characters they meet. And of course, there are those who will seek the full experience without missing a single piece, immersing themselves fully in the game’s bottomless depths, and pushing the idea of “role-playing” to its limits. Although the true genius of Demon’s Souls and Dark Souls only appears in light of the complete work, no one approach is more valid than another. The community of Souls enthusiasts is compelling in the diversity of its members, and in their different approaches. This same community was able to discover the countless secrets peppered throughout the game: the community aspect is even present within the adventures themselves, through an online system that allows players to leave messages for other participants. The adventures are solitary, but players stick together and may even help one another. This paradox attests to the originality of the experience dreamed up by the FromSoftware teams.

With this book, our goal is to provide an overview of the various pieces that make up the Souls series. As we see it, it was impossible to adopt a precise perspective to present a general approach, as the games’ power derives from the way the different ingredients interact to produce a richly detailed and coherent work. This is why, piece by piece, we will work to provide a global vision of the series and what it offers us, and to grasp its essence. We will start by going back to the very beginning.

Dark Fantasy: From Novels to Video Games

If the Souls series is saturated in a gloomy and bewitching ambiance, it is because the games deftly make use of a genre known as dark fantasy. Dark fantasy began a literary sub-genre of fantasy. It is difficult to pin down with a single definition, since the many novels that claim the mantle of dark fantasy often share only tenuous links. However, there are some common threads, particularly in the way that the stories tend to be darker and less dualistic than the classic stories told in fantasy. For example, dark fantasy may integrate emphatically horrific elements, or blur the line between good and evil. The general atmosphere is disquieting, melancholy, and sometimes depressing or nightmarish. Evil and demonic creatures abound: ghouls, zombies or even vampires. The characters do not have the qualities of a traditional hero, driven by noble values or defined by epic adventures; they present a darker and more violent side, sometimes even world-weary and pessimistic. Generally speaking, works of dark fantasy tend to weave fantastical stories that draw from the dark and ambiguous side of humanity, and the philosophical questions that can arise: our relationship with superior forces, fear of nothingness and the unknown.

The style of the story and the universe may sometimes vary greatly from one work to the next. For example, it is easy to distinguish the dark fantasy scenarios such as those in the Souls games, which take place in a medieval universe typical of fantasy–with an extra touch of horror–, from creations that take place in a contemporary context. Anne Rice’s The Vampire Chronicles and some of Clive Barker’s works (Everville) are good examples of this. However, this does not take away from the obvious connections between these two types of representations. A striking example of this is when a dark fantasy author such as Neil Gaiman (Sandman, Coraline) works on the script of Robert Zemeckis’s film Beowulf. Beowulf, originally a Germanie epic poem, is a classic example of the genre in question here, in particular due to the way this epic poem blends horror imagery within the fantasy atmosphere, through the monster Grendel and his mother.

Historically speaking, the origins of dark fantasy date back to the beginning of the twentieth century, with Gertrude Barrows Bennett’s novels and short stories (The Nightmare, The Elf-Trap, Behind the Curtain, etc.), the first of which were published in 1917. Then, the genre progressed as Howard Phillips Lovecraft, now considered the pioneer of modern horror, concocted some terrifying short stories. He is above all famous for his Cthulhu Mythos, in which he imagined an original cosmogony populated with monstrous extraterrestrial gods, including Cthulhu, an immense creature that is part-octopus, part-dragon. Lovecraft’s strength lay in his ability to suggest the indescribable, to evoke visceral fear of the absolute, of what is beyond human imagination. In the way that he blended fantasy with the language of fear, while illustrating themes such as fate, forbidden knowledge and control by superior malevolent forces, Lovecraft inspired numerous generations of dark fantasy and horror authors.

Some of his close friends also worked in the horror-fantasy hybrid genre. Clark Ashton Smith, for instance, produced several collections of short stories, including Zothique, Xiccarph and Hyperborea. August Derleth is another example, though he is more commonly known as Lovecraft’s first publisher and the one who came up with the name “Cthulhu Mythos” to refer to the author’s imaginary cosmogony2. Derleth himself continued Lovecraft’s work with stories that take place in the same universe. In a register closer to traditional fantasy, Robert E. Howard’s adventures of Conan the Barbarian (or Conan the Cimmerian) have dark fantasy elements3. Michael Moorcock’s Elric of Melniboné series, which first appeared in 1961, is also considered one of the first important works in the genre.

The expression “dark fantasy” itself did not enter common usage until the 1970s, until the 1970s, when two authors in particular claimed the genre. The first, Charles Lewis Grant, used a horror register in a contemporary setting, and received several literary awards (Nebula, World Fantasy, etc.) for some of his short story collections, such as Shadows and Nightmare Seasons. The other, Karl Edward Wagner, was an editor and writer who continued the work of Robert E. Howard and was made famous by his series telling of the travels of Kane, an antihero immersed in a world of witchcraft from the heroic fantasy genre. Since then, numerous works of dark fantasy have been published, such as Glen Cook’s The Black Company, Brian Lumley’s Dreamlands, David Farland’s The Runelords, and Stephen King’s The Dark Tower. The latter, known for his horror stories such as The Shining and Carrie, has always cited Lovecraft as one of his inspirations, and considers him to be the master of horror. Recently, the Game of Thrones series from George R. R. Martin greatly popularized the dark fantasy genre through a realistic depiction of geopolitics and the ambiguity of human relationships, in a medieval context with a magical backdrop.

However, the genre soon broke free of the bounds of literature. Comic books, for example, count among them some distinguished examples, including Neil Gaiman’s graphicnovels The Sandman, or the Black Moon Chronicles from French writer François Marcela-Froideval, with the first volumes illustrated by Olivier Ledroit, and then later Cyril Pontet and Fabrice Angleraud. The American animated series Gargoyles, Angels in the Night was also recognized in the 1990s for its dark qualities and reinterpretation of mythological elements–a rather daring idea for a series aimed at the general public; however, we must remember that the beginning of the 1990s saw Bruce Timm’s excellent animated adaptation of Batman, which is exemplary in its dark atmosphere and writing.

The field of role-playing also drew from dark fantasy. Many Dungeons and Dragons worlds fit within this genre, such as Ravenloft and Dark Sun. In addition, we can cite the World of Darkness series, or Stormbringer, which takes place within Moorcock’s Elric of Melniboné universe. Dark fantasy was also a staple of “choose your own adventure” books, also known as gamebooks. Many series such as Fighting Fantasy or Sorcery! depict grim environments, where they force players to venture through sinister labyrinths to confront evil creatures, in horror-like settings.

Video games themselves were quick to adopt dark fantasy, particularly using medieval-type atmospheres steeped in sorcery. Prior to the Souls series, the Diablo series from Blizzard studios was the most well-known example of the genre. The first episode appeared in 1997. With its accessible gameplay, unpredictable dungeons, richness and unique style, it reinvented the “hack and slash” genre, whose distinguished ancestors include Rogue (1980) and Gauntlet (1985). Diablo was also distinctive due to its richly detailed atmosphere, marked by a punishing descent into hell, within gloomy underground passageways populated with demonic monsters. Other series are worthy representatives of dark fantasy, such as Legacy of Kain or The Witcher. Created by Polish publisher CD Projekt, this series is presented as an adaptation of Andrzej Sapkowski’s novels and short stories on the saga of the witcher, alias Geralt of Rivia. Although it is rooted in a fantastical medieval world typical of dark fantasy, populated with ghouls, vampires and magicians, The Witcher offers a more raw and realistic approach than the poetic, ethereal and nightmarish vision of Souls.

In this way, dark fantasy cannot be defined in a precise manner, due to all of its different manifestations. Dark fantasy nevertheless represents the dark side of fantasy in general, and reveals the other side of the mirror, while refusing to give in to Manichaean dualism. Evil, whether a monstrous incarnation, a symbolic suggestion, a damnation, or corruption, generally plays a prominent role. Stories do not necessarily have happy endings; rather, they aim to reflect the nuances and ambivalence that define our existence. Moral ambiguity, instinctive fears and darkness pervade this genre, as it rejects classical formats. In short, dark fantasy stirs up the deepest elements within us, thereby offering fertile ground for imagination and reflection.

Although it originated in the West, this genre sparked the interest of some Japanese creators. Adept at blending cultures and reappropriating Western cultural codes, they soon produced their own vision of the genre. In the manga field, Kazushi Hagiwara’s Bastard!!, Kentarō Miura’s Berserk, or the more recent Claymore by Norihiro Yagi, are looked up to as references. In video games, Yasumi Matsuno’s Vagrant Story and Tactics Ogre made their mark. But the history that interests us begins in 1994, when a small Japanese development company made the decision to produce a Western-style role-playing game in the dark fantasy universe.

FromSoftware: The Inheritance

Founded in 1986, the FromSoftware studio was first launched to create office software and applications. It was only at the beginning of the 1990s that the company decided to venture into the world of video games. President and producer Naotoshi Zin put together a team of around ten people, including writers Shinichiro Nishida and Toshiya Kimura, illustrator Sakumi Watanabe, and main programmer Eiichi Hasegawa. Most of them were united by a common passion for dark fantasy, board games and video games, in particular the Wizardry series, computer role-playing games created by Sir-Tech that saw great success in Japan. FromSoftware’s creatives set out to pay homage to these works that had inspired them, by creating a role-playing game with Western influences that contrasted with local productions in the genre (Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, etc.).

The first King’s Field was released only in Japan for PlayStation in December 1994. Without reaching record sales, it still received attention, due to its release just a few days after the launch of Sony’s new console. The first-person perspective in a true 3D environment was unique at the time in console-based role-playing games. The genre was primarily reserved for computers, with influential American games such as Ultima Underworld, the Might and Magic series and Lands of Lore, which were popular with gamers. King’s Field was highly influenced by these games, thus clearing the way in this relatively unexplored field. It received mixed reviews: some players liked the challenge posed by the game, its harsh approach, its dark and suffocating atmosphere, its pared-down style, and the freedom of exploration it provided; others were put off by its austere graphics, its extreme difficulty, the lack of explicit instructions, the labyrinthine construction and the slowness of movement and fights. Depending on people’s perspectives and approaches, some of the game’s good qualities were seen as flaws, and vice-versa. FromSoftware had done all it could to respect the philosophy of role-playing games, with complex dungeons to explore, strategic fights and a dark ambiance.

In many ways, King’s Field prefigured the essence of the Souls series. A dark fantasy universe, pared-down narration, uncommunicative and depressed characters, levels brimming with traps, a battle system revolving around patience and observation (with a stamina bar preventing incessant attacks) : all of these elements were already present in FromSoftware’s first creation. Differences included the first-person perspective, but also the continuous musical accompaniment: Souls would opt for primarily silent exploration, with the exception of some precise locations and boss fights. The two series are nevertheless very similar in spirit.

In spite of the undeniably Western origins of the universe and gameplay of King’s Field, the first episode was not released in the United States, simply because when PlayStation finally appeared on American soil in September 1995, King’s Field II had already been released in July of that year. It only took a few months for the FromSoftware team, still around ten people, to create this sequel, often considered the best of the series. Although the formulas were identical, slight improvements were made to the graphics and sound, the level design became even more perverse, and loading time was eliminated from the exploration, all of which helped produce an episode popular with fans of the series. Released in June 1996, King’s Field III was less successful, in spite of interesting attempts to offer a more varied open world, which unfortunately took away from the claustrophobic dimension that characterized the first two games. King’s Field II and III were released in the United States as King’s Field and King’s Field II respectively, to avoid displeasing the Americans, who hadn’t been given access to the original episode. For each, reception was mixed. The series remained little known in the United States, and only met critical success among certain players.

After producing the three first episodes in quick succession, FromSoftware set aside the King’s Field universe to launch its other pioneering series, Armored Core, which remains its most substantial franchise to this day, with more than a dozen games. Although this series of futurist action games with mechas (Japanese robots) does not bear any resemblance to the oppressive universe of King’s Field, the development studio did not abandon the idea of continuing with dark fantasy role-playing games. Shadow Tower, which came out in Japan in June 1998, and then in the United States in October 1999, is strikingly similar to an episode of King’s Field. It offered the same first-person perspective, the same grim, sinister universe (in spite of some more contemporary elements like firearms) and the same system of exploration and combat. However, Shadow Tower added some new features that distinguished it from its predecessors. Experience points were replaced with automatic stat evolution based on enemies killed, through the collection of their souls, echoing the future Souls games. Other similarities include the absence of music during exploration, or the introduction of equipment durability and weight, which requires players to repair it regularly.

The fourth King’s Field came out on PlayStation 2 in October 2001 in Japan, and in March 2002 in the United States (where it was called King’s Field: The Ancient City to avoid confusion), and even in Europe in March 2003. The spirit of the series remained, and the FromSoftware team, then made up of around sixty people, was able to take advantage of the expanded capacity of PlayStation 2 to provide an even more immersive adventure, with more carefully considered artistic direction. It was in the design of this episode that illustrator Daisuke Satake (one of the most important Souls artists) first made his mark. He also worked on Shadow Tower Abyss, the sequel to Shadow Tower, which was sadly only released in Japan in October 2003. Even though this sequel was more successful than the first, the public’s general disinterest for this style of game led FromSoftware to set aside role-playing games like King’s Field. The development studio decided to focus on its pioneering series, Armored Core, as well as various mecha games such as Metal Wolf Chaos and the Another Century’s Episode series, the medieval survival horror Kuon, the 2009 beat ’em up Ninja Blade and more traditional J-RPGs like Enchanted Arms.

These were not always very successful, and were sometimes downright mediocre. FromSoftware began to acquire the reputation of a second-class developer with limited means. This would be difficult to deny, since, in spite of the relative success of the Armored Core games, which allowed the studio to grow significantly, the FromSoftware productions were never cutting-edge or expertly finished. History has nevertheless proven time and again that little developers sometimes transcend their technical weaknesses to produce unforgettable game experiences, from Grasshopper Manufacture (Killer7, No More Heroes) to Access Games (Deadly Premonition) and Cavia (Drakengard).

With relentless integrity and passion, FromSoftware was able to pay homage to a whole swath of American sub-culture and dark fantasy with its King’s Field and Shadow Tower series. These games, although somewhat mediocre in appearance, provided both challenging and beguiling adventures to those who took the time to immerse themselves in them. Over the years, the studio slowly improved its formula. Six years after Shadow Tower Abyss, Demon’s Souls was released, and its success allowed numerous players to discover this Japanese interpretation of a Western genre. Hidetaka Miyazaki’s creation was original in many ways, but still continued in the direct vein of FromSoftware’s previous productions. That’s why we took this little historical tour: understanding a work’s origins also helps with understanding the work itself, and with grasping the lifeblood that drives it. The Souls games are so rich that, to analyze them, it’s important to work our way through them bit by bit.

First Steps Into theSoulsWorld

Boletaria, Lordran, Drangleic. These names refer to the three universes that greet players in Demon’s Souls, Dark Souls and Dark Souls II, respectively. Three games, three settings, yet one single philosophy and very similar experiences. Like King’s Field and Shadow Tower, the Souls games are role-playing games that offer an arduous trip to the core of a threatening and degenerate world. Courage, patience and perseverance are required to take part in these adventures. Yet the journey is worth the attempt, because the feelings we derive from the experience override any of the dangers we encounter.

Before jumping right into one of the games, players must be aware that the more they involve and immerse themselves, the greater their end reward. The Souls games cannot be seen as a simple hobby to fill a half-hour on a dull evening. For the best possible experience, one must understand that the Souls games are among those that require constant attention and only yield their treasures to the most committed. Indeed, this is the only prerequisite before taking the great leap. No need to be a seasoned player to embark on the adventure: just agree to (role-)play along. The path is long and treacherous, but it is also bound to leave its mark.

The Souls atmosphere grabs you from the very first moments. From the chilling music in the introductions to the very first backdrops, with evocative, desolate landscapes, the games each give off a somber and melancholic feel. Within this fantastical medieval setting, dark fantasy finds one of its most inspired manifestations. Corruption and curses form the roots of the stories told. Forgotten gods, demons, darkness, damned creatures: the lexical field of the universes deftly blends supernatural imagination and horrific elements. The monstrosities that stand in our way seem straight out of a nightmare, from ghouls to giant spiders, and phantom knights to rotting dragons. Like the genre’s most representative works, the Souls games offer few rays of light. Living in these ruined worlds where time seems to stand still, the characters are weary of their existence, and the rare ones who still clutch to the faint hope of evading the curse eventually sink into madness.

Players are set loose in this hostile context with minimum explanations. Unlike King’s Field, the perspective here is in the third person. Equipped with a shield and a chosen weapon (sword, dagger, axe, bow, magic staffs, etc.), they must choose the best approach for exploring the cursed lands of Boletaria, Lordran or Drangleic. Using hand-to-hand combat or distance attacks, mobility or defense, the choice is theirs, and strategy can be changed at any time during the adventure. For every vanquished enemy, the character collects a certain number of souls, which allow them to move up a level and improve the characteristics of their choice (vitality, endurance, attack, dexterity, magic, etc.). If players die, they reappear at the last point of connection (the Archstones in Demon’s Souls or the Bonfires in Dark Souls). It is then possible to retrieve lost souls in the same place where a character perished, as long as you do not die again on the path, since the enemies all reappear.

Death is therefore not the end of the game, but it is not without consequences. The character controlled by the player can take on two forms: a Body Form, which, among other things, gives access to all online interactions, and a Soul Form (Demon’s Souls) or hollow4 (Dark Souls). This second state entails some penalties specific to each game, which we will detail in the second chapter. Through this cycle of attempts and failures, with no “game over,” death is an integral part of the mechanics of the three adventures, but it is not to be taken lightly. It acts as a reminder: danger is everywhere, and players must be constantly on their guard and avoid rushing.

Step by step, players progress, surrounded by the sound of the wind, clinking of armor, the wheezing of zombies. They gather objects, weapons and equipment from the corpses strewn across the ground, which foreshadow the fate awaiting those who lack the strength of will to complete the quest. Senses are heightened, moments of respite are rare, and the game cannot be paused. The game constantly saves the player’s progress, and all actions are irreversible. Every encounter with an enemy requires maximum concentration, and stress reaches its peak when a boss appears, accompanied by its specific musical theme, which heightens the intensity of the confrontation. Relief and satisfaction only increase with each level overcome. The environment itself is torturous and filled with traps to avoid or secret zones to explore. Bit by bit, players absorb the universe’s logic, memorizing enemy placement, level design, the numerous parameters to consider for equipment management and object utility.

In Souls, players embark on a quest for learning. They learn about maneuverability, gameplay, and level construction. They also gain insight into techniques used by enemies and bosses, as well as their own limits, and self-control. Leveling up is not sufficient to become stronger; players themselves gain real experience with each obstacle overcome. This same experience can also serve other players who have chosen to attempt the journey. On the ground, messages left by other players, whose brief spectral appearances sometimes intersperse the game, providing valuable indications, or proving to be red herrings. Traces of blood on the ground, when touched, show the final moments of a departed player. These elements can help overcome obstacles and fight the solitude that pervades the inhospitable lands.

In spite of the online interactions, hazy and ephemeral, players are undeniably alone. The few characters we meet along the way do not always inspire confidence, and rare are those who offer to lend a hand. Some, who have sunk into madness, may even turn on players. Although the general atmosphere is fascinating, it also weighs heavily. From castle ruins to foul swamps, dark caverns and nefarious forests, the various spaces inspire only discomfort, unease and desolation. Primitive terrors–fear of the dark, claustrophobia-and reminders of perspective–immense structures, the feeling of smallness in relation to the settings–alternate to remind players that they are not in control of their environment. A solitary saga in the depths of darkness.

The reasons for the player’s presence in this world are unclear. With a common objective, to lift a curse, the Souls stories form a dense backdrop that must be reconstructed in order to understand what is really at stake in these ravaged worlds. Players must listen closely to the tales of the characters they meet, carefully read the descriptions of objects and equipment, and painstakingly observe the settings and appearance of enemies. The stories fade into the background, almost invisible, and players get the feeling they must discover everything on their own. They are free to explore, reflect, and act. Some actions may have irreversible consequences, and the story’s background reveals itself subtly, insidiously as players progress. No choice of dialogue here: the character is silent. The Souls games prefer what is unsaid, unspeakable, at the risk of obscuring entire possibilities from players who are used to clear and direct narration. Chapter III of this book will strive to provide as comprehensive as possible a description and detailed interpretations of these backdrops, richer than their background status may suggest.

In this introduction to the series, we aimed above all to provide an overview of its essence and philosophy, through its origins, but also to provide a preview of what awaits players that start an episode. Every Souls game offers a different adventure and more or less significant variations in the game mechanics. But they all obey a single logic, a single sensibility. The quests, lined with pitfalls, offer an unforgettable voyage through profound and seductive dark fantasy worlds. Every detail has been meticulously wrought to deliver an intense gaming experience brimming with treasures and secrets. The series bears witness to a long, passionate creative process, which says a good deal about the intentions of the developers and helps us better understand why the Souls are unique works in the landscape of video games.

1 Although this work is titled Dark Souls: Beyond the Grave, it also covers Demon’s Souls, since the latter was formed from the same mold, has the same creator, and could be considered the first episode of the “series.”

2 To refer to his cosmogony, Lovecraft used a different, invented expression “Yog-Sothothery,” in reference to another of the divinities: Yog-Sothoth.

3 Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard were all published in the American magazine Weird Tales in the 1920s and 1930s.

4 The term “hollow” is often used by players to describe the “zombified” appearance of the main character when he or she is not human. This is actually a misuse of the term. In the story, “hollow” corresponds to the end status of this undead form, when the human being has definitively devolved into madness.

The Authors

Damien Mecheri

Passionate about films and video games, Mecheri joined the writers team of Gameplay RPG in 2004 by writing several articles for the second special edition on the Final Fantasy saga. With this same team, Damien continued his work in 2006 for another publication known as Background, before continuing the adventure on the Internet in 2008, with Gameweb.fr. Since 2011, in addition to working as a radio journalist, he has written articles on the music for a number of works published by Third Éditions, such as Zelda. The History of a Legendary Saga, Metal Gear Solid. Hideo Kojima’s Magnum Opus, The Legend of Final Fantasy VII and IX, From Rapture to Columbia, and he has written the book The Legend of Final Fantasy X, and co-written Welcome To Silent Hill – Journey into the depths of Hell.

Sylvain Romieu

Curious by nature, a dreamer against the grain and a chronic ranter, Romieu is also a passionate traveler of the real and the unreal, the world and the virtual universes, always in search of enriching discoveries and varied cultures. A developer by trade, he took up his modest pen several years ago to study the characteristics and richness of the marvelously creative world of video games. He writes for a French video game site called Chroniques ludiques, particularly on the topic of RPGs, his preferred genre.

CHAPTER ONE

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

The Father of the Series: Hidetaka Miyazaki

In May 2014, Hidetaka Miyazaki succeeded Naotoshi Zin as president of FromSoftware, after the studio was purchased by Kadokawa Shoten. This was a highly significant promotion for the person who had led the company’s most successful project, Dark Souls. And yet, he did not lose from view what had attracted him to the field: an insatiable creative drive. In spite of his new status within the studio, one of the conditions he requested and was granted was to remain creative director of his new project: Bloodborne. This allowed him to successfully design this spiritual successor to the first Souls game, while also assuming his new responsibilities. Given his drive to work and create, it is not surprising how quickly Miyazaki moved up through the ranks.

As a child, he lived in the city of Shizuoka with his parents. Curious and eager for knowledge, the young Miyazaki would check books out from the library, since his parents had modest income, and could not afford to buy them. He quickly began reading books beyond his age level, and he delighted in working out and imagining the parts he couldn’t understand. He discovered gamebooks like the Sorcery! series and role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons, and developed a passion for the world of dark fantasy and the gloomy stories where knights fall prey to darkness and despair.

In university, he received a degree in social science, and was hired as an account manager for the American company Oracle Corporation. At this time, he also began to develop an interest in video games, and a friend introduced him to ICO. This game, created by Fumito Ueda, was a revelation to Miyazaki, and showed him the medium’s potential. At 29, he began looking for a job in the field, and snapped up one of the rare job offers available. It was not by chance that he soon developed an interest in FromSoftware, the studio that had proved its abilities with the King’s Field and Shadow Tower series. Miyazaki was hired in 2004. He first began working on the shooter series Armored Core as an event planner for the Last Raven episode, which came out in 2005 on PlayStation 2. His dedication, determination, and abundant ideas earned him the trust of his superiors, who promoted him to the directorship of Armored Core 4, and then Armored Core: For Answer. It thus only took him one year to reach the most important role in video game creation. With the support of Takeshi Kajii, a producer with Sony, Miyazaki was able to fulfill his bold dream and direct the creation of a work infused in dark fantasy: Demon’s Souls. In this chapter, we will cover this piece of history.

Video game creation requires many people–from tens to hundreds. Every member of the team plays an important role and contributes to the overall performance. The process is complex, and everyone can pitch in ideas and suggestions. One cannot deny the truly collaborative nature of this work. We nevertheless chose to focus our examination of the genesis of Demon’s Souls and Dark Souls on the figure of Hidetaka Miyazaki.

Cinema is a fitting analogy here: film productions also rely on bringing together talent and coordinating various artistic and technical departments to produce collective works that achieve the vision of a single creator. Although directors are not solely responsible for the success of their projects, they must assemble the workers and artists at their disposition in order to bring their imagination to life. The general direction, staging choices, writing, and all of the major steps of the creative process depend on their instructions and decisions. Video games sometimes work in a similar way, and some auteurs have made a name for themselves, such as Hideo Kojima (Metal Gear Solid) and Suda 51 (Killer7, No More Heroes). The same goes for Hidetaka Miyazaki, whose method reflects the passion that drives him and his penchant for building, supervising and validating every detail in his developing work.

Without the programmers, designers and other members of the FromSoftware teams, Demon’s Souls and Dark Souls would never have seen the light of day. But without Hidetaka Miyazaki, these same people would never have produced a game like this. For a better idea of why this is, we’ll go behind the scenes in the creative process of these games, which have already left their mark on video game history.

Demon’s Souls

In 2006, producer Takeshi Kajii of Sony Computer Entertainment paid a visit to the FromSoftware offices. As a fan of the King’s Field series, he couldn’t help asking if another episode was being made. It was a simple question, but it led to a more constructive discussion than expected. It had been a few years since FromSoftware had produced dark fantasy-based games; the last had been Shadow Tower Abyss, released only in Japan in 2003. The studio had preferred to focus on its other seminal series, Armored Core, as well as other mecha games, such as Metal Wolf Chaos and Chromehounds.

The discussion ended with the decision to create a game developed by FromSoftware, produced by Sony. This is how the Demon’s Souls project, designed for PlayStation 3 and the Japanese market, began in early 2007. Early on, however, the project was plagued with many pre-production issues. Hidetaka Miyazaki, who was a coder on this new project, was frustrated, hoping he could take the reins on this new project and thus apply his numerous ideas. With the support of veteran producer Masanori Takeuchi (Evergrace, Enchanted Arms, Ninja Blade), he was named creative director. This was the same position he had occupied on Armored Core 4, which was popular for the new features and ideas it brought to the series. Although he had just started with the company less than three years earlier, Miyazaki had quickly shown that he was capable of carrying through on large projects while giving them a fresh perspective. So while he was simultaneously producing Armored Core: For Answer (which would be released in March 2008 in Japan), the inexhaustible Miyazaki poured his heart and soul into Demon’s Souls, constantly overseeing all of the aspects of the developing game.

Its creation would take place over two years. In total, almost eighty FromSoftware employees participated in the project. This number attests to the relatively modest nature of this production, a far cry from the Western blockbusters whose teams are composed of hundreds of people. After reigning supreme over the console market until PlayStation 2, many Japanese studios struggled to adapt to the PlayStation 3 – Xbox 360 era, both in integrating with the new hardware and managing resources. As FromSoftware had never been a large studio, Demon’s Souls was designed as a medium-sized project, directly benefiting from the direct support of Sony. Major team members included main programmer Jun Itô (Armored Core 4), sound designer Yuji Takenouchi, composer Shunsuke Kida, but also some studio veterans such as one of the system designers, Shinichiro Nishida, who had worked on the first of the King’s Field games.

Legacy and Renewal

By mutual agreement, producer Takeshi Kajii and creative director Hidetaka Miyazaki decided to create an entirely original game rather than a sequel to King’s Field, which would nevertheless serve as inspiration. The idea was to avoid being bogged down by the inherent constraints of sequel design, such as needing to conserve the same gameplay, universe or general storyline. Although the new project would reflect FromSoftware’s philosophy, it had to be conducive to innovative ideas, with total creative freedom.

Even though Miyazaki has often declared that he did not base himself on any particular game in the preproduction, it is clear that the King’s Field series provided a solid foundation for Demon’s Souls. Its general philosophy–an arid, ruthless Western-style RPG set in a suffocating universe-as well as many of the game mechanics, served as a transition from the old to the new game: the little-known duo of Shadow Tower, another FromSoftware creation that shares DNA with the King’s Field games, also served as a source of inspiration, particularly in the way players collect souls to improve their character’s traits.

The main subject matter behind the creation of Demon’s Souls is nevertheless older. Both Miyazaki and Kajii were great fans of “choose your own adventure” books. Notable examples include Fighting Fantasy and Sorcery!, in particular the stories set in the fictional world of Titan. They also hold great esteem for the first C-RPGs1, and particularly the Wizardry saga, which was highly successful in Japan. It was this love of Western-style medieval fantasy and dark fantasy that led FromSoftware to create the King’s Field series in the 1990s. These common roots gave rise to Demon’s Souls, along with Miyazaki’s more personal sources of inspiration, such as old Anglo-Saxon myths (King Arthur, Beowulf, etc.) and seminal dark fantasy works such as Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian.

A Good, Old-fashioned Challenge

In a time of player-friendly games–long tutorials, checkpoints, low levels of challenge–, Miyazaki and Kajii agreed to revive an anachronistic RPG approach in Demon’s Souls. As with the King’s Field games, the idea was to echo the spirit of the C-RPGs, and more specifically the “dungeon crawlers”–role-playing games centered around the exploration of labyrinthine dungeons filled with monsters and objects to unearth–which were very popular in the 1980s.

However, even though the FromSoftware game developed the reputation of being very challenging, so much so that the word of mouth around the game focused almost entirely on this point, the developers never intended to present such a difficult and unremitting challenge for the simple pleasure of punishing the player. Miyazaki regularly protested against this misunderstanding, as in an interview he gave to Game Informer: “Having the game be ’difficult’ was never the goal. What we set out to do was strictly to provide a sense of accomplishment. We understood that ‘difficulty’ is just one way to offer an intense sense of accomplishment through forming strategies, overcoming obstacles, and discovering new things.” For Kajii, the desire was to “wake up the gamers [...] used to easy games,” as he declared to Famitsu during the production of Demon’s Souls.

It was in this respect that the “permanent death” concept was considered for a while. The game’s debug menu (an interface that provides access to various elements of the program for debugging) retains many traces of this, which suggests that this idea could have been implemented in the game, possibly as a special mode. In reality, “permanent death” was quickly abandoned since it was excessively demanding. To provide the sense of accomplishment they sought, they settled on “die and retry,” which imposes a cycle of failures that heightens the joy of success and the exultant feeling of having played well and accomplished a feat.

Miyazaki didn’t feel that Demon’s Souls needed to be insurmountable and discouraging. Quite the reverse: players needed to understand that their defeats stemmed from an error on their part rather than the ferocity of the enemy. A lack of attention and observation, briefly throwing caution to the wind, haste: these factors are the most common causes of death in Demon’s Souls. Sneaky traps and ambushes abound, but they simply underline the fact that players must always be on their guard. Patience and self-control were defined as essential qualities for those entering the Kingdom of Boletaria. This led to the system of retrieving souls after a defeat, which makes players increase their caution to avoid being killed again and definitively losing all of the souls they have collected.

Liberty as a Game Philosophy

Since his childhood, Miyazaki had been fueled by gamebooks and works that were complex beyond his years, in which he had to fill the holes with his imagination. He developed a taste for ambiguous, difficult stories that require serious reflection to get to the heart of the matter. Of course, this trait is shared by video games derived from the board game tradition, including King’s Field. During the preproduction phase, Miyazaki built an entire dark fantasy world, with its historical background, its specific characters and hopeless atmosphere. The backdrop was relatively fleshed out, but it would remain in the background of Demon’s Souls: a puzzle intended for curious players.

This universe, Chapter Three of this book, only reveals itself in the background, through dialogues with non-player characters (NPC), descriptive texts paired with objects and details visible in the background and architecture. The narration is terse and environmental, which reflects both Miyazaki and FromSoftware’s preferences as well as the player-driven experience found within traditional role-playing games.

Freedom drives the game’s experience. The game’s storyline is intentionally de-emphasized, as the developers worked to revive the type of immersion that players feel in board games such as Dungeons and Dragons, where participants draw from the context provided to use their imagination and truly embody their character. The adventure becomes highly personal, very different from that of any other player. It was this dimension that interested Miyazaki and that he wanted to transpose into Demon’s Souls.