Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

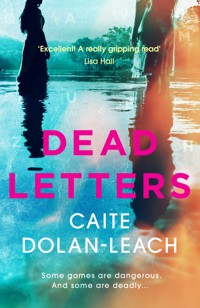

SOON TO BE A THRILLING NETFLIX DRAMA STARRING LUCY HALE 'I LOVE THIS BOOK ON SO MANY LEVELS' CAROLINE KEPNES, AUTHOR OF NETFLIX HIT YOU Some games are dangerous. And some are deadly... Ava doesn't believe it when the email arrives to say that her twin sister is dead. It just feels too perfect to be anything other than Zelda's usual manipulative scheming. And Ava knows her twin. Now, Ava must return home to retrace her sister's last steps. But her search turns into a twisted scavenger-hunt of her twin's making. Letter by letter, Ava unearths clues to her sister's disappearance, which reveal a series of harrowing truths from their past - truths both of them had tried to forget. A is for Ava, Z is for Zelda, but deciphering the letters in-between is not so simple... Readers are going wild for DEAD LETTERS ' Utterly brilliant! Very similar to Gillian Flynn and Tana French. Absolutely loved it! ***** 'Highly addictive plot, this is definitely a "one more chapter" book' ***** 'Very clever an addictive' ***** 'Wow what a book!!!' ***** 'Great twists ... LOVED it!' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 559

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Caite Dolan-Leach is a writer and literary translator.

She was born in the Finger Lakes and is a graduate of Trinity

College Dublin and the American University in Paris.

Dead Letters is her first novel.

From this, one can make a deduction which is quite certainly the ultimate truth of jigsaw puzzles: despite appearances, puzzling is not a solitary game: every move the puzzler makes, the puzzlemaker has made before; every piece the puzzler picks up, and picks up again, and studies and strokes, every combination he tries, and tries a second time, every blunder and every insight, each hope and each discouragement have all been designed, calculated, and decided by the other.

—Georges Perec, Life: A User’s Manual

Un dessein si funeste, s’il n’est digne d’Atrée, est digne de Thyeste.

Atreus might not stoop to such a gruesome plot, but Thyestes sure would.

—Crébillon, Atrée et Thyeste, quoted byEdgar Allan Poe in “The Purloined Letter”

Contents

Dedication Page

Dead Letters

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

Dead Letters

1

A born creator of myths, my sister always liked to tell the story of how we were misnamed. She was proud of it, as though she, as a tiny blue infant, had bent kismet to her will and appropriated the name that was supposed to be mine. My parents were trying to be clever (before they lost the ability to be anything other than utterly miserable), and our names were meant to be part of our self-constructed, quirky family mythology. A to Z, Ava and Zelda. The first-born would be A for Ava, and the second-born would be Z for Zelda, and together we would be the whole alphabet for my deluded and briefly optimistic parents, both of whom were located unimpressively in the middle: M for Marlon and N for Nadine. My father was himself named for a film star, and with his usual shortsighted narcissism he sought to create some sort of large-looming legacy for his burgeoning small family. Burgeon we would not.

Born second, I was destined for the end of the alphabet. But my sister was Zelda from her first screaming breath, wild and indomitable until her final immolation. A careless nurse handed my father the babies in the wrong order, so that his second-born was indelicately plopped into his arms first, and I was christened Ava. I say “christened” purely as a casual description; my mother would have thoroughly lost her shit had any question of formal baptism been raised. My parents were good pagans, even if they weren’t much good at anything else.

Clearly delighted with this strange twist, my father insisted that we keep our misnomers; he said that the family Antipova would turn even the alphabet on its head. My mother, predictably, lay surly and despairing in her bed, counting down the seconds until her first gin and tonic in eight months. Even now, I can’t really blame her.

The seatbelt light dings, and I unbuckle in order to root around in my bag for my iPad. I’ve read the email so many times I have it memorized, but I still feel a compulsion to stare at the words on the shimmering screen.

From: [email protected]

June 21, 2016 at 3:04 AM

Ava, honestly the whole point of you having a cellphone is so that I can call you in an emergency. Whicf this is. If you’d pick up your goddamn phone, I wouldnt have to tell you by EMAIL that your sister is dead. There was some type of fire following one your sisters drunken binges, and apparently, she didnt make it out. If you leave paris tomorrow, you might make it time for the service.

I can’t really tell whether the misspellings are because a) Mom is drunk, b) she never really learned to type (“I’m not a fucking secretary. I didn’t become a feminist so I could end up tapping out correspondence”), or c) the dementia is affecting her orthography. My money is on all three. I’ve never seen Nadine Antipova, née O’Connor, greet any kind of news, either good or bad, without a quart of gin in the wings. The death of a daughter, especially that of her preferred daughter, has probably rattled even her. My guess is that she was already three sheets to the wind when they told her, and she wasn’t able to get through to me on my cell because she either couldn’t remember the number or misdialed it. She would have had to toddle upstairs to the decrepit old MacBook gathering dust on what used to be my father’s desk. She would have lowered herself into the rickety office chair and squinted at the glare of the screen. After several frustrating minutes and false starts (and probably another slug of gin), she would have located Firefox and found her way to Gmail, if she didn’t try her old and defunct Hotmail account first. She probably would have sworn viciously at the screen when asked for her password. Nadine would consider the computer’s request for her to remember a specific detail as personally malicious, a couched taunt regarding her slipping faculties.

She would have tried to type something in, and the password would have been pre-populated, because Zelda had, in her own inconsistent and careless way, tried to make our mother’s grim life a little easier. And then, drunk, aggravated, angry, and frightened, my mother wrote me a bitchy email to tell me that my twin sister had burned to death. And if that’s how she told me, I can only imagine how my father found out.

My first thought on reading the letter was that Zelda would have appreciated that death: This was exactly how she would have chosen it. It was a fitting end for someone named after Mrs. Fitzgerald, who died, raving, when a fire destroyed the sanatorium where she had been locked away for a good chunk of her life. How Bertha Rochester dies, in rather similar circumstances. As children, we played Joan of Arc, and Zelda built elaborate pyres for straw dolls decorated as the teenage martyr (Zelda was Joan; I was always cast as the nefarious English inquisitors). Death by fire was the right death for visionaries and mad-women, and Zelda was both. My dark double.

But then, because I know my sister, I read between the lines.

The whole thing was so very Zelda. Too Zelda. When I finally reached my mother on the phone, she slurrily told me that the barn had caught fire with Zelda trapped inside. The barn out back that Zelda had transformed into her escape hatch when she could no longer stomach being in the house with our ailing, flailing mother. I knew she liked to retreat to the apartment on the second floor, to stare out the window and chain-smoke and drink and write me emails. The fire investigators seemed to believe that she passed out with a cigarette (Classic, Zelda!) and the wood of the barn and all the books she kept up there caught fire in the dry heat of the June day. Burned alive on the summer solstice. With the charred remnants in plain sight of half the windows in the house, where my mother can’t help being reminded of Zelda, even with her brain half rotted and her liver more than half pickled. My sister couldn’t have contrived a more appropriate death if she had planned it herself. Indeed.

The drinks trolley rolls by, blithely smashing into the knees of the long-limbed. Compact and travel-sized, I have plenty of space, even in the cramped and ever-diminishing airline seats. I secure myself a bland Bloody Mary in a plastic cup, wondering for the dozenth time about the name of this precious, life-giving elixir—related to the gory bride we conjured in mirrors as girls?

I swirl the viscous tomato juice among too many ice cubes and not nearly enough vodka, sipping through the tiny red straw. I love these thin mixing straws. I love their parsimony. I’m trying very hard not to think about what I’m leaving and where I’m heading. Traveling this way across the Atlantic has always seemed cruel; you leave Europe at breakfast and arrive in the United States in time for brunch, exhausted and ready for happy hour and dinner. The sun moves backward in the sky. You face your bushy-tailed friends and relatives having been awake for fifteen strenuous hours, having spent those hours exiled in the no-place of airports and airplanes. Forever returning to Ithaca. Or Ithaka. I will be collected from the tiny airport and brought to my childhood home, fifty yards from where my twin sister is supposed to have crackled and sizzled just a few days earlier—all before dinner. I wonder if the wreckage is still smoldering. Does wreckage ever do anything else? We have been twenty-five for nearly one month.

I will walk into the house, instantly accosted by the smell, the smell of childhood, my home. I will walk upstairs, to my mother’s room. If it’s even one minute after five (and it likely will be, by the time I make it all the way upstate), she will be drunk or headed that way, and I will sit with her and pour each of us a hefty glass of wine. We will not discuss Zelda; we never do. Eventually (and this will not take as long as “eventually”) she will say something devastating, cruel, something I can’t really brush off, and I will leave her. If I’m feeling vindictive, I will take the wine with me, so that she will have to carefully make her way downstairs for another bottle, risking cracked hips and the possible humiliation of failure.

I’ll walk outside with that bottle of wine, and I will look at blackened timbers of that barn. I will scrutinize that dark heap of ashes. And then I will start trying to unravel my sister’s mystery, and I will find her, wherever she is hiding. Come out, come out, wherever you are. What game are you playing, Zelda? She has always been so bad with rules.

From: [email protected]

September 5, 2014 at 8:36 PM

Darling Sister, Monozygotic Co-leaser of the Womb,

Well, is Paris all and everything? Does it glimmer the incandescent sparkle of mythology and overrepresentation? I’m betting yes to both, at least as far as you’re concerned. Let me guess what you’ve been up to: You landed, disposed of your baggage, and went immediately for a triumphant stroll along the Seine—you know how you always must be near water in moments of jubilation, a genetic gift from our maternal forebears, beach striders all—you strode, nay, frolicked along those hallowed banks until your blisters popped, and then, because you are our mother’s daughter, you promptly sought out some sort of cold alcoholic beverage. And, because it is very important to you to blend in with the locals but also to feel historically rooted in “authenticity,” I bet that drink was . . . Lillet! Or, very possibly, Champagne, but I would put money on the chance that both shame and frugality prevented you from slapping down sixty or seventy euros for an entire bottle of the bubbly. I’m betting you sipped your Lillet, tried out your perfectly acceptable French, basked in your escape, pretended you didn’t want anything else to drink, and bought that Champagne from some charming “authentic” wine store on your way home to the tiny shoe box you will be living in until you get this Francophilia out of your system (or until you squander Dad’s hush money and must retreat home). All the while resolutely not thinking of what happened before you left us. Why you left us. I’m right, Ava, n’est-ce pas?

Well, I’m very happy that you’re fulfilling your dreams and whatnot, even if it did mean forsaking your beloved twin sister, whom you left languishing in the hammock with a touch of the vapors at the thought of bearing sole responsibility for our matriarch. I know you always say that she prefers me, but GOOD GOD, you should see how she’s moping around without you. I really think she thought that you were bluffing, that you weren’t serious about this whole graduate degree thing and were all along planning to settle in with her out at the homestead, to mop her brow and hold her hand as she trembles through the daily DTs, slowly losing all sense of self. Oh, but her bug-eyes when your suitcase came down the stairs! She can’t remember much, but she remembers THAT betrayal. Jilted, she kept waiting for weeks in quivering, agonized suspense, disbelieving that she could be abandoned with such a flimsy explanation!

I’m not trying to guilt you (I would never! Not. Ever. Not after everything that happened . . .) but am instead attempting to sketch a portrait of how life will proceed hereabouts in your absence. I’m going to stay in the trailer (I will! No one can force me out! Not even that damned bat) rather than move back to the house on the vineyard. Mom’s in iffy shape, true, but I’m planning to be there every day, as you know, and she’s still lucid enough to manage in the nights. I think. The Airstream is less than a mile away, in any case—I should be able to see the plumes of smoke rising if she burns down the house, ha ha! I’ve considered hiring someone to stay with her a bit and take care of the more unsavory activities (diapers are just around the corner, really), but I’m reluctant to dip into the dwindling Antipova/O’Connor pot o’ gold. Barring some sort of harvest miracle with the grapevines, I think the years of a profit-yielding Silenus Vineyard might be behind us, Ava. Seriously. But at least the failing entrepreneurial venture gives me the illusion of a profession, which is very useful at the few grown-up cocktail parties I attend, and almost nowhere else. And it ostensibly gives me somewhere to be. And obviously keeps me in wine. No wonder the proto-satyr Our Debauched Father was so enthused by the prospect of running a vineyard. He was not entirely foolish, that man.

Well, I’ve been rambling—I’m sitting and typing on this antique laptop, here on Dad’s old desk. I’ve been trying to teach Mom, but she can barely remember to pull up her undies after she pisses (better than the other way round, I suppose!), so I imagine I’m mostly trying to entertain myself. When I finish, I will have to go collect Mother from her sun throne and tempt her with just enough booze to get her inside without a battle. Time to rip off the Band-Aid. I’m sure you have some Brie and baguette to feast on—but remember, not too much! Never! If she were (t)here, our mother would remind you that she recently noticed a slight wobble in your upper arm, and at your age, you can’t afford to overindulge. The irony.

In all seriousness, I miss you madly. Surely you WERE joking about this whole graduate degree thing?! And surely we can start talking again?

Eternal love from your adoring twin,

Z is for Zelda

Several hours, another flight, and another tinny Bloody Mary later, I stare through the tiny airplane window at the swath of lakes stretched out below. The engines are so loud that my jaw and temples ache. When the plane tilts for its final approach into the Ithaca airport, I can see all the Finger Lakes in a row, a glistening, outstretched claw catching at the late-afternoon sun. I am, of course, late; the immigration lines in Philly took hours, my bag was the last on the carousel, and I missed my connecting flight. And the next flight to Ithaca was canceled, which happens fifty percent of the time. More often in winter. The airport broke me, spiritually; microwaved Sysco food and eight-dollar beers make it impossible to relax, everything else aside. Food and drink are my only sources of true and deep (if conflicted) pleasure. In that I resemble my father. I am actually grateful to be in this noisy plane, circling above the lakes like toothpaste circling the drain. Spiraling down.

I wonder again whether it was a mistake to come alone. Nico offered, in his tender Gallic way, in bed last night. Tentative and generous, as always. This place would rip him to shreds. He would be baffled and caught off guard by such wanton cruelty. He would politely try to drink the wine, but his glass would stay half full all night. He’s not a snob, but he is French. And above all else, Nico is well-mannered; he would be completely out to sea amid my friends and family, who would be too busy chewing one another to pieces to bother with Continental pleasantries. I’d love to have him with me, to know that at the end of each brutal day he would be waiting upstairs in my fluffy, too-white bedroom, waiting to comfort and console me after the most recent onslaught. At that thought, my stomach does a little flip, doubting my decision to leave him behind. I told him that if I have to stay longer than a couple of weeks, he can come visit then. More incentive for me to get the hell off Silenus Vineyard, and away from Seneca Lake. As if I needed the additional encouragement.

The wheels touch down, and I look grimly toward the airport windows. I wonder if my father will actually show up to fetch me, as he has promised to do. I can already taste the sharp, acidic local Pinot Grigio that my mother keeps in the fridge, and I realize how badly I want it.

My father, Marlon, is entrenched outside the airport, napping on one of the benches. His straw fedora is pulled down over his eyes, and I have a feeling that he’s been here like this for a while. I nudge his feet to wake him, and his eyes open sloppily beneath the hat.

“Little A!” he coos, sitting upright. He’s wearing all linen, his shirt and pants elegantly rumpled. His sharp green eyes are not so sharp right now. I haven’t seen my father in more than two years, but he looks more or less the same. His dark hair is maybe lighter, the lines around his eyes a bit deeper, but he’s still the effortlessly debonair rake he has always been. And, as always, at the sight of his smile, I feel incredibly tempted to forgive him for his shortcomings, his abandonment. My mother spent a decade and a half forgiving this man, and she is not a forgiving person. I marvel at his magnetism and wish I had inherited that, instead of his green eyes and fondness for comestibles.

He leaps up as soon as his eyes focus on me, surprisingly buoyant for someone who has lost a child. But I know he will be chipper and all smiles, performing for me. Wanting to be liked. He’s about to scoop me up in a big hug when he seems to recollect himself, remembers how things are between us. He is still slender, though I can detect the beginnings of a paunch beneath the creamy linen shirt when I give him a slight, distant hug, encumbered by my carry-on. He squeezes me, tightly.

“Hi, Daddy. Glad you could make it.” I really do try not to inflect this with sarcasm, but it can’t be helped. He pretends not to notice. My father loathes conflict. Probably why he prefers his second family to his first.

“A, I’m so, so sorry. God, I can’t imagine . . .” He grabs my shoulders and peers intently at my face. I realize that I might cry, in spite of myself, and I gently shuck him off. His face is lined: the tragic patriarch, kingdom in ruins, daughter dead.

“I know, Dad. It’s . . . okay. Let’s head over the hill.” Old family joke. As in: “We’re all over the hill out in Hector.” Less funny now to be sure, and doubtless only to degrade with the years. Much like our family. “I’m sure Mom is . . .” I’m not quite sure how to finish the sentence. I’m sure Mom is a mess, I’m sure she’s already had at least one bottle of Pinot Grigio, given how late I am, I’m sure that there is going to be a scene of remarkable nastiness when Marlon turns up at the house. He makes a show of gallantly taking my suitcase from me and heads toward the parking lot. Effortlessly, he hoists the bag over his shoulder, an easy demonstration of masculinity.

“You didn’t bring much with you, A.”

“I packed in a hurry. Besides, I still have a bunch of stuff at the house. And I can always wear Zelda’s.”

He flinches visibly and refuses to meet my eyes. Nico balked, too, when I said this last night as I was flinging random clothes into my suitcase, while he perched in nervous concern on the edge of my bed, clearly worried for my sanity. I can see why it might be something of a faux pas to don my sister’s outlandish clothes and flit through the house looking just like her mere days after her death, an alarming corporeal poltergeist. But I always wear Zelda’s things. It would be a concession to her scheme if now I didn’t.

“Have you spoken to your mother?” Marlon asks.

“Briefly, on the phone last night. She was pretty disoriented, so I didn’t get much out of her.”

“Has she been doing . . . okay?”

“What, haven’t you called her?”

“I tried, Little A. She hung straight up on me.” He pauses. “Can’t say I blame her. Must be hell.”

“I don’t really know how she is, Dad. I don’t talk to her all that often. She’s been very . . . angry since I left for France, and Zelda said she has fewer and fewer good days.”

“Listen, kiddo, I’m . . . sorry that you have to deal with this. Her. It’s not fair. On top of everything . . .” Marlon seems unsure how to continue. This is as close as I will get to an apology from him. He’s very good at apologies. You realize only later that he has accepted responsibility for exactly nothing.

“Let’s not talk about it, Dad. I’d like to . . . just enjoy the sunshine.” We’ve reached the car, which he optimistically parked in the pickup and drop-off area. He has a ticket, which I’m sure he will not pay. This part of the world has yet to adopt the post-9/11 attitude typical to transit areas in the rest of the country, and airport security rather lackadaisically enforces its modest anti-terror protocol. In New York City, Marlon’s car would have been towed and he’d be in police custody by now. But here in Ithaca, just a ticket.

He has rented a flashy convertible, of course. My dad likes to travel in style, regardless of finances, seemliness, tact. He tends to think of any economic restriction as a dead-letter issue, a rule that does not apply to him.

“Nice ride,” I say. He grins mischievously as we load my bags and ourselves into the car and speed off. I hope he’s okay to drive. I haven’t driven in two years and don’t even have a driver’s license, but I might still be the better choice if he’s drunk. He seems reasonably coordinated, though, and once we’re on the other side of the city, we’ll coast along traffic-free dirt roads, kicking up dust and free to veer across the graded surface as much as we like. I relax as we speed down Route 13, Cayuga Lake on our right.

“So so so. Paris! How the hell is it, squirt?”

“About what you’d expect, Dad.” I shrug.

“C’mon, it’s one of the greatest cities in the world! That’s all you have to say about it?”

“It’s far away from Silenus. Even farther than California.”

He ignores the frosty tone in my voice. He is buoyant, but I can hear the strain in his throat as he tries to be cheerful for me. “Always so lighthearted, Little A,” he teases. “Levity, oy vey.” He whistles a tune as we drive through the city, the breeze ruffling his thick black hair, which isn’t curly like ours but, rather, wavy. When we learned that curly hair was a recessive gene, Zelda and I started speculating about our heritage. But there are too many other stamps of Marlon’s paternity on our genes, and we abandoned the possibility of filial mystery as an exercise in wishful thinking. The letters of our DNA signify our origins, even if they can’t inscribe our futures.

“What did you do while you were waiting for me?” I ask, though I know the answer. I’m wondering if he’ll lie.

“I stopped in to see some old friends, and we went out for a bite to eat.”

“Oh? Where did you go?”

“Uh, what’s that place downtown called? With the cheap margaritas?”

“Viva.”

“Yeah, very average Mexican food.” He grins. “But it’s the only place open between two P.M. and dinner in this one-horse town.”

“The only place with a bar, you mean,” I say, half-teasing.

He smiles again. “I’d forgotten how charmingly . . . sedate it is ’round these parts.” He signals with his blinker, and we ride silently for a moment or two.

“How is your ‘old friend,’ Dad?” I ask. He blinks. He’s a very good liar, and I can tell he’s considering whether to lie now. But I’m betting he’ll come clean. Because I’m older now. Because my twin sister just died. My twin sister, who, incidentally, inherited this particular talent for deception.

“Sharon, you mean?” he says.

“Who else?”

“She’s okay,” he says uncertainly. We’ve never had a real conversation about the woman he was fucking during my middle school years. I’ve wondered more than once whether he knows that Zelda and I knew. Our mother certainly did.

“That’s good. Do you still see her often?”

“No,” he says softly. “It’s been years.”

“And how is the third wife? Maria?”

“She’s well. The girls are well too. Six and eight, if you can believe that! Scrappy little things. I’ll show you the pictures on my phone, later.” He pauses. “Blaze is a bit of a terror, and Bianca sometimes reminds me of you, when you were little. She’s so . . . neat.”

“Napa is treating you well, then?”

“Yeah, yeah. It’s pretty great! The vineyard’s doing really well—we were in Wine Spectator last month.” I know. We own a vineyard, too, and have had a subscription to Wine Spectator since 1995. Which he knows; he insisted on the subscription, and left us with the bill. “You should come out and visit, while you’re back in the States. I know Maria wants to see you girls.” We both flinch at his use of the present tense, the plural.

“Maybe. I need to get back to Paris kind of soon, though.”

“It’s summer, Little A! Live a bit! You never relax. Your studies can wait until fall, surely.” He nudges me with his elbow, annoyingly.

I nod. “Sort of, I guess. I’m working on my dissertation now, though, so I’m busy. I’m interested in the intersection of Edgar Allan Poe and the OuLiPo movement, their shared emphasis on formal constraint—”

“Poe never struck me as particularly restrained,” Marlon interrupts, presumably thinking himself to be clever.

“Not restraint. Constraint. Specifically, I’m interested in lipograms and pangrams. I’ve got a theory that while both are obviously important for OuLiPo texts, they might appear unconsciously in Poe’s works. So far I’ve focused mainly on alliteration and repetition, and because Poe’s work is explicitly invested in the unconscious—”

“A pangram—that’s like ‘the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog’?” Marlon interjects. I expect he’s trying to impress me.

“That’s the idea. So far I’ve been working on this one essay he wrote on poetry—”

“It sounds really erudite, Little A, and I can’t wait to talk about it more. But can’t you take a break? It’s summer, and, well, your sister . . .”

I capitulate. Marlon is not remotely interested in what I spend my days thinking about.

“Yeah, well, Zelda was the relaxed one. I was the responsible one.”

“You still are, sweetie,” he says, trying to be comforting.

“No, I’m the only one now.” I suddenly feel like my mother, nastily baiting this man into feeling like shit. “I’m sorry, Dad. I’m just not . . . sure . . .” I trail off, watching in the mirror as Ithaca disappears behind us and we head up the highway on the other side of the lake.

“It’s okay, kiddo. You say whatever you have to.” He pats my knee. I realize that since greeting me, my father hasn’t looked at me once. As if he can’t. I root in my oversized bag for my sunglasses and put them on, in case I start to cry. But as I gaze out at the dazzling spray of too-green leaves and the shimmering water, I suspect that I’m not going to.

2

Brutally jet-lagged and insufficiently buoyed by Bloody Marys, I can’t keep my eyes open and doze off somewhere on the dirt roads that will take us across the narrow, rugged span between the lakes, and I wake up just as we hit the top of the hill overlooking Seneca. The view is spectacular, with the sun about to set on the west side, and my breath catches a little, as it does every single time I make this drive. This is the longest I’ve been away from home: twenty-one months. I glance over at Marlon, and though he has his sunglasses on, I think he’s been crying. Weeping, even. I’m startled and distressed by this—his charming, fun-loving façade so rarely cracks, and when it does, I feel as though my world is being unmade. Maybe Marlon knows this, because as he sees me waking up, he instantly transforms, flashing me one of his brilliant, toothy smiles. I know that he loved living here, loved our subpar vineyard. Even loved my mother and us girls. But his love for us is tempered by years of discord and cruelty, whereas the love he feels for this modest patch of ground is unadulterated. I smile back at him, because in spite of myself, I’ve missed it too.

The car skates over the dirt roads as we descend lower and lower, closer to the lakefront. There are fields of grapes all around us, and the pleasant hum of billions of insects thrums in whirring cadence. The temperature drops suddenly in mysterious swaths of air, and goosebumps ripple on my forearms and thighs as we whip through them, warm cold warm. I can smell cold water.

Silenus Vineyard is up on the hill, with acres of vines stretching out below the tasting room, which is fronted by a rustic deck looking out at the water, scattered with a few picturesque barrels for ambience. It doesn’t have much of a yield, and the wine is barely mediocre, even for the Finger Lakes.

I peer as closely as I can at the grapes as we drive by to see what Zelda has been up to in the last twenty-one months. It’s hard for me to imagine my unpredictable and self-indulgent sister tilling the land like a good farmer, but she’s managed to keep the place from total destitution, basically on her own. I wonder if he has been here, if he has been living in the Airstream trailer with her, if he is the one who organizes the spring trellising and the autumn harvest. I have to assume so; Zelda has never cared much for schedules, and I can easily picture her frittering away all of May and June drinking Pimm’s cocktails on the deck and swearing that she’ll move the catch wires tomorrow. Unless she really commits to doing something, and then she is an unholy terror. A terrier. I know I will have to see him soon, maybe today, and I squirm, thinking of what I’ll say.

My father clears his throat awkwardly.

“You know, it’s the weirdest thing,” he begins. “I think I must be losing it.” He pauses. “It’s just that while I was at the bar . . .” He shakes his head, his waves of hair bouncing fetchingly. He doesn’t go on.

“What?” I prompt.

“It’s silly.”

“What is?”

“I thought I saw your sister.” I keep my face as blank as possible. “Or you, of course. But she walked like Zelda. I don’t know, all loose.” Marlon chuckles at himself. “Ridiculous, right?”

“Grief does funny things to your head,” I answer, trying to betray nothing. Did Zelda intend for him to see her? Is she in Ithaca? Or California? I lean back in the seat, thinking about my sister. Thinking about whether she would even bother to toy with Marlon. After he left, it was almost like he stopped existing for her. Whereas I pined.

Dad pulls into the long, steep driveway that leads to the tasting room and the house snuggled next door. Nadine and Marlon built the house after they built the tasting room and the new cellar, solidifying what the real priorities were going to be. A place to drink, then a place to live. My mother, with her exacting, nitpicky taste, designed the house with an architect friend from the city, and each window, molding, and corner mirrors her love of right angles, modernism, abstraction. It is not a warm, cozy house. And next to the house is the barn.

The blackened shell of that barn appears as Dad crunches into the gravel parking area. The view is partly obscured by the house, but I can see charred timber poking up from the ground. I catch a glimpse of yellow tape cordoning off a large chunk of our lawn. A police car is parked near the rubble, and someone official is rootling around the periphery, looking fiercely intent and professional. My hands suddenly start to tremble and I don’t want to get out of the car. Zelda, what the fuck did you do?

Dad wordlessly takes both of our suitcases from the trunk, and I realize in a vague panic that he’s planning to stay here, under the same roof as Mom. He seems shaken, and I’m actually relieved to see his equanimity at least a little disrupted. His first-born child is, after all, presumably smoking in the wreckage of the barn he built himself, that one achingly long summer when my mother couldn’t bear his presence in the house. Her house. Dad is resolutely not looking at the barn as we go inside. Or at me.

“Mom?” I call uncertainly, trying to guess where she’ll be. The sun is setting, and I wonder whether she will have gone ahead and eaten without us. I don’t know if Betsy, our lumpy, matronly neighbor, will still be here; I called her after I got off the phone with my mother and asked if she could go over to the house, make sure Mom had some food and didn’t stumble down the stairs. Betsy was all comforting murmurs and practical country clearheadedness on the phone; she knew of course, had seen the fire from her house, just a mile away. She’d already been over and had just come home to pick up a frozen casserole when I called. She wanted to tell me the whole story, but I had been desperate to get off the phone, to slink into bed with Nico and let him mumble to me in his accented English.

“Betsy?” I call.

“Upstairs!” someone, presumably Betsy, answers. Dad sets the suitcases down by the door and looks around skittishly. I can see him summing up what has changed in this house. The medical-looking banister railing. The locks on certain cabinets in the kitchen. My mother’s favorite print, a Barnett Newman reproduction that used to hang in the hallway, gone. Zelda, in a blind fury, tore it down and threw it into the lake during a particularly violent argument, before the dementia was diagnosed, while Mom’s moods were still inexplicably abrupt. I can tell that Marlon does not want to go upstairs.

“I’m, uh, gonna look around for a minute, use the bathroom. I’ll bring us up a bottle and some glasses in a minute,” he says uncomfortably, scuttling away from the staircase and my mother’s silent, spiderlike presence upstairs. “Maybe it would be a good idea to warn her that I’m here, kiddo. She, uh, might not be all that happy to see me.”

I nod. I know he’ll go straight to the liquor cabinet once I’m out of sight, but he’ll be disappointed to find a combination lock barring his entry. Zelda informed me in one of her chatty emails, with a gleefully vindictive tone, that she installed it after my mother nearly OD’d on Scotch last year. Apparently, Nadine forgot that she had already been drinking wine and popping sedatives all day and almost boxed her liver with a bottle of Glenmorangie. Marlon will just have to rustle up something with a lower alcohol content from the fridge.

I skip upstairs, feeling the familiar grooves of the wooden stairs beneath my feet. I have instinctively taken off my shoes; my mother loathes the presence of footwear in her once-pristine Zen paradise. She could be driven to apoplectic rage by someone sitting in the living room with boots on their feet. The house is definitely dirtier than it was during my childhood; I suspect Zelda fired the housekeeper I’d hired from Craigslist before leaving for Paris. I feel grit and dust accumulating on the soles of my bare feet, and as I touch the banister, a layer of grime coats my fingertips in a seamless transfer. But the stairs are the same beneath me and I feel each creak in my body with intense recognition.

Mom and Betsy are outside, on the balcony that opens from the library. Betsy has her back turned to the barn, but my mother is facing it full-on, glaring belligerently at the scar in our lawn, zigzagged with crime-scene tape.

“Hi, Betsy, thanks so much for this,” I say, preparing myself for the inevitable hug as Betsy lurches out of her chair to greet me. “Really, you’re a lifesaver.” I wonder at my choice of words, but Betsy smooshes me to her breasts with a squeeze.

“Oh, Ava, I’m so sorry about—about your sister!” She instantly begins to cry, her substantial chest heaving up and down, her brown doe eyes watering. I pat her shoulder, trying to create a crevasse of space between our bodies. Her sweat moistens my shirt.

“Thanks. I’m so grateful you were here.” I pause. “Hi, Mom.” I lean in to kiss her cheek, interrupting her stare toward the barn. “How are you?”

“Goddamnit, Zelda, what the fuck did you do to the barn? How many fucking times do I have to tell you not to smoke up there?”

I flinch, knowing I should have expected to be confused with my sister. “Mom, it’s me, Ava,” I say patiently. “I just got here, I flew from Paris?”

“Very cute, Zelda. God, you’re exactly the same as when you were four, always trying to hide behind your sister whenever you screwed something up. I’m not an idiot, nor am I insane. I expect you to deal with that”—she gestures imperiously toward the barn—“immediately. And with none of your usual dramatic bullshit, please.”

I glance at Betsy, who is unable to tear her eyes from this scene. The rapt rubbernecking of good neighbors. I turn to her.

“Betsy, thanks again for everything. I know she can’t have been easy the last day or two. And thank you for calling the fire department. Who knows . . . what could have happened.”

“Oh, Ava!” Betsy carries on huffing and puffing without skipping a beat. “It was so terrifying, the whole barn just lit up like that! I rushed over as quickly as I could but—your sister!”

“Zelda, I need more wine,” Nadine says sharply, interrupting Betsy’s whimpers. I ignore her.

“How are your kids, Betsy?” I ask.

“Kids? Mine? Oh, they’re okay, I guess,” she titters. “Rebecca just started working as a dental assistant, actually. And you remember Cody?” she says, fishing. Yes, I do. Cody was one of the irredeemable assholes who graduated with me. I’d love to tell Betsy how he used to follow the one openly gay kid in our school around, whispering “Faggot” and smacking his ass.

“Yup. How is he?”

“He lives in San Francisco now. With one of his college roommates,” she announces proudly. I suppress a giggle. That’s perfect.

“Zelda, for Christ’s sake,” Nadine interjects.

“I’ll deal with her now, Betsy,” I say. A gentle dismissal. She seems grateful.

“No, no, of course, Ava. It was no problem. Anything I can do, really. I’ll stop by tomorrow with more food.”

“You don’t have to do that,” I say quickly. “Really, you don’t.”

“No, no trouble. I’ll check up on you then. Nadine’s already eaten, and there’s more casserole in the fridge.” That should make it easy not to eat. She dabs at her tears with the collar of her oversized batik-print muumuu. “At least I got her to eat this time. Last time I was here, she wouldn’t touch a thing.”

“Thanks, Betsy. Oh, and Marlon’s downstairs—you can say hello on your way out.”

Betsy’s face tightens perceptibly—she’s one of the few people who isn’t taken in by my father’s charm; she has a long memory and can’t forgive Marlon for the way he left. It makes me want to like her more.

“I will, of course. And, Ava? My sincere condolences,” she says earnestly and hugs me again. She bobs her head and waddles through the glass doors, trundling her way downstairs. I flop into the Adirondack chair she has vacated, glad that it faces the tasting room, though it is unpleasantly warm from her body.

“You look pretty good, Mom. All considered.”

“Don’t take that tone with me, Ava,” she says.

I smile widely. “So you did know.”

“As I said, doll, I’m not insane. Not entirely. I just despise that woman, with all her clucking and sanctimonious . . . good-naturedness.” Mom has to pause for the right word, but I can tell she’s lucid-ish. “She’s thick as a plank and doesn’t have the good grace to realize it. I’ve been listening to her prattle for the last twenty-four hours about how it’s going to be fine, you’ll be here soon, et cetera.” She rolls her eyes in exasperation. “I came out here and parked in front of the barn, hoping that it would scare her off. But she’s got to do the right thing. God, and that casserole . . .” She shudders theatrically.

“What happened, Momma?” I ask.

“How the hell should I know? I slept through the whole thing. Goddamn drugs your sister gave me.” Mom takes a slug from the wineglass in her hand, which trembles as she clutches the stem. Reflexively, I look around for the bottle, to gauge how much she’s had. She catches me looking.

“Jesus, you’re worse than your sister. At least she has the manners not to make me drink alone. You haven’t ended up in AA, have you, Little AA?” She’s sneering, making fun of my father’s nickname for me, and goading me into drinking with her. I know it, and it doesn’t change the fact that I want to.

“Dad’s on his way up with glasses and a bottle,” I say casually, and enjoy watching her flinch.

“Marlon is here? The big fish that got away?” She tries for a lighthearted tone, but I can hear the anxiety in her warbling voice. She touches her face in instinctive, irrepressible self-consciousness, the gesture of a woman who knows she doesn’t look good.

“Got in this morning. Surely you must have known he would come home for his daughter’s funeral.”

“Yes, I gathered he would. Surprised he didn’t bring that new ball and chain of his.”

“Maria is hardly new, Mom. They’ve been married almost eight years.”

“Maria? I thought her name was Lorette.”

“That was my girlfriend when we met, Nadine,” my father says from the doorway. He’s studying her with a strange expression on his face; I can’t remember the last time they saw each other, but I know she has to look shocking. She is so thin.

“Oh, of course, I remember,” Mom says automatically. I know she doesn’t, but she will work very hard to convince us otherwise.

“You could be forgiven for forgetting. The relationship was very brief,” I snipe. Nadine snorts. Dad holds up a bottle of sparkling wine and three Champagne flutes with a slightly sheepish look on his face. The glasses hang suspended between his fingers, clinking magically. I love that sound.

“There’s only sparkling in the fridge,” he apologizes. I nod, giving him permission. He puts the glasses down on the deck railing and deftly divests the bottle of its wire cap and cork with a practiced series of movements. All three of us cringe at the jubilant sound, and Mom and Dad both flick their eyes toward the barn, as though that Pavlovian signal will summon Zelda, perhaps even from beyond the grave. Champagne is her favorite drink, of course. Though this is obviously a sparkling wine, made in our own cellar. Dad pours our delicately burbling wine into flutes and distributes them, my mother first, then me. I lift my glass defiantly.

“Well, family. Cheers.” They both look at me blankly, and I turn my head toward the lake, draining my glass in a hearty gulp.

From: [email protected]

Subject: Mademoiselle Pout

October 1, 2014 at 12:45 AM

Dearest Begrudgeful, Silent Sister,

Don’t you think this a little silly, Ava? You really are milking the whole thing quite atrociously, as though we were still in high school. I mean, yes, it all goes back to high school, so perhaps you get SOME leeway for behaving like a hormonal hot mess, but surely with our blossoming maturity you can LET IT GO? If it makes any difference, I’ll get rid of him; just say the word.

In other (frankly more interesting) news, our mother is a psycho. And a lush. Last night I had to scrape her out of the field, raving and half clothed, drinking a bottle of that atrocious Faux-jolais Nouveau that Dad insisted we try to manufacture, in spite of the fact that it always tastes like grapy horse piss. And yet, out of some dark-seated nostalgia, Nadine insists on reproducing it every year, as though this vintage will be drinkable. It’s like she thinks if she could just produce a bottle that was even a little palatable, Marlon would reappear, and she could sit on the deck and watch him work the fields, as ever. Her very own contadino.

Anyway, last night she was yelping and sobbing, insisting that she wanted to return to the earth or somesuch. I think she was trying to make it down to the lake, quite possibly to throw herself in. One of these days I may just let her. But as it was, I gave her some of her “medicine” (what a useful euphemism for heavy-duty sedatives!) and dragged her back to bed, the whole while listening to her screech like a demented banshee. You can bet I poured myself a substantial tumbler of the good stuff. I’m not just being selfish: Her wee pills give her a respite, as well as me!

Autumn has really dug in its heels; the leaves are leached of their chlorophyll and are whirligigging their way to the ground at an alarming rate. And Paris? I Googled photos of Les Tuileries to see what it looks like (that’s where we wanted to live when we were little, right? Though I can only assume you live near the garden, rather than in a fairy fortress within it, as previously planned), and it does seem very picturesque. Still, hard to beat the view from Silenus. The harvest was brutal; another year or two of this and I’ll be dribbling into my Riesling like Momma. We’ll see what we get out of it. I’m guessing it will be more of the same.

But really, are you planning to not talk to me for the rest of forever? Or just until you wind up in bed with a chain-smoking, shrugging Parisian? Really, Ava, it’s not that big a deal, what happened. I’m over it. He’s over it. Weirdly, I find myself washing and changing your sheets on a regular basis. I barely even wash my own. What do you think that’s about?

Your repentant, embryonic other half,

Z is for Zelda

I bundle Nadine into bed, though I don’t lock the door behind her—Zelda wrote that she has started sleepwalking lately, but I can’t bring myself to lock her in. What if there’s another fire? After setting Marlon up in the guest room, I creep outside with a flashlight. Everything still smells of smoke, and I head toward the barn’s remains. It’s still warm; summers have been getting hotter and hotter here, though many of our die-hard Republican neighbors still refuse to comment on why this might be. Zelda speculated about what it would do for the grapes (“Did you know French Champagne growers are buying up real estate in the south of England? They’re predicting that the growing conditions will be more Champagne-esque than Champagne in twenty years! Do you think we’ll be, like, the next Chianti?”). I’m barefoot, so I make my way gingerly across the lawn, avoiding bits of burnt wood and other debris. I scan the flashlight over the area and finally squat down a few yards from where the barn doors would have been. There’s a small yellow flag poked into the burnt wood and ash.

Shutting my eyes, I can see the structure perfectly; I imagine sliding open the heavy doors, padding my way across the cement floor where we kept all sorts of menacing farm equipment, and climbing up the steep ladder rungs to the loft.

Marlon built the barn with some rustic fantasy of cramming the loft full of hay, keeping a few goats and sheep downstairs in the quaint mangers he constructed. But he left before we ever acquired either hay or critters to feed with it, and the barn became ad hoc storage for the ancient tractor and backup steel wine drums and random bits of equipment that weren’t used often. Zelda colonized the upstairs as her own stately pleasure den, insisting on loading books and furniture up through the hay chute in her teenage stubbornness. She had a few cast-off futons up there, a big worktable, some chairs, lots of ironic art (mainly featuring baby farm animals) that she had picked up at the Salvation Army in Ithaca. Even in her teens, she’d felt trapped in the house with our mother and had hidden out here whenever they fought. Used to watching her abandon projects, I observed her rehabilitation of the barn with surprise. It seemed terrifically unlike her.

As high school ended, she began to invite people over to what she had started calling the Bacchus Barn (Zelda names everything). My mother would grit her teeth in passive-aggressive fury, staring out the window at the lights in the barn, the sound of music keeping us awake well into the night. Nadine never knew what to do with Zelda. Or this property.

We had a collective story about how Silenus came to be, cobbled together from four different people with radically different narrative designs. The gist of it, the median account of that particular yarn, is this: My mother’s money paid for Silenus, though it was my father’s vision. Marlon was not the sort of man my mother usually went for; she liked very Waspy men, men who had been to law school and golfed on the weekends. Men who knew how to tie a variety of knots and always specified “Tanqueray” when they ordered a martini. Marlon Antipova, perennially relaxed and pathologically easygoing, all sun-weathered and full of vim, was the antithesis of what she always thought she had wanted in a partner. But when Nadine’s mother died after a lengthy, debilitating illness (Parkinson’s), leaving her an orphan, she pulled up stakes and moved to New York. At thirty-two, she had to decide what to do with herself and her money. When Marlon sauntered into that bar in the Village where she sat slurping gin and tonics and avoiding the silent, carpeted apartment she had rented on the Upper West Side, she saw escape, from herself and her past. She launched herself without blinking into a haphazard life with the adventurous Florida-born wanderer.

My father was never a practical person, but he had aspirations: a dangerous combination. He gave an impressive impersonation of a vagabond bohemian, all the while zealously keeping his quiet ambitions just behind that convincing veneer of exceptional recklessness. I’ve spent quite a bit of time imagining that scene, so pivotal in our family story. A time when they wanted each other, when the future hadn’t barreled disastrously into their plans. Zelda and I used to tell the story to each other, handing off the narrative like a cadavre exquis.

I would always start: Marlon’s pickup pulled onto the graveled shoulder that would someday be the bottom of our driveway. The lake spread out below him and my mother, and Marlon crunched the truck to a halt as they neared the dusty For Sale sign drummed into the ground. A telephone number was written out in Sharpie ink, with no area code in front of the seven digits. Locals only, the sign was subtly suggesting.

“Is this your grand surprise, then?” Nadine asked him, trying not to sound either disappointed or eager. She sought to remain impassive, to never betray what went on behind those cool blue eyes of hers. To neither lose her temper (as she was prone to do) nor reveal her excitement, her happiness, which was a new experience for her. Having spent the last few years watching her parents’ unsightly decline, she was free now, for the first time since early childhood. Still young(ish), with some money and self-determination, she could do whatever she pleased. And what pleased her most was this sly, smooth man with a ponytail and an easy smile. How strange that he would choose her, with her stiff manners and the tight kernel of anger she carried with her. That he would go rapping, rapping on her apartment door at all hours of the night, and saunter into her bedroom with a bottle of bourbon and the southern drawl that he revealed, seemingly only for her, for moments of intense intimacy beneath her expensive down comforter. She had never allowed anyone so fully into her life, her inner world, and sometimes she would stare at Marlon in disbelief that he wanted her.

Zelda would take over then, to explain our father: Marlon always pretended not to notice these guardedly fond moments but felt more confident in her attachment to him whenever he caught that intense, shrewd gaze. This woman was everything he wasn’t, everything he aspired to. She ordered drinks without looking at the menu—she knew what she wanted and was not particularly worried about price. There was never any question of whether she could afford it, whether the bill would arrive and she would come up short. Marlon had left behind a number of threatening business partners and outstanding debts (monetary and otherwise) in the swampy town of his childhood and had disappeared into the anonymous horde of penniless musicians here in New York out of necessity. He imagined a future where he would sit and look out at his own land. He had learned a word, years ago, pedigree, that he would sometimes, after five or six drinks, slosh around on his tongue. Nadine, who kept herself aloof and separate, and so rarely allowed him to know what went on in that inscrutable head of hers, was classy in a way that Marlon found hopelessly erotic. Her pale Irish skin reminded him of marble, and her ramrod posture of a statue. So different from the bronze, wiry girls he had tussled with as a young man, in smoky dive bars and tropical rainstorms.

“It is grand, isn’t it?” He allowed a strand of black hair to fall across his face as he leaned across the cab toward her. “C’mon, you. Hop on out. I’ll give you the tour.” Nadine obliged, and Marlon snatched a picnic basket from the bed of the borrowed truck. With his other hand, he led her down into the field, tall with alfalfa and wildflowers. “They’re selling the whole property,” he finally said, watching Nadine’s face carefully as she assessed everything. He had learned not to push her too quickly or too hard; when she felt cornered, she balked, like some trapped wild animal. Nadine simply nodded her head, her eyes measuring each blade of grass with that sharpness he had come to expect. He spread out the picnic blanket and sprawled on it, popping the cork on the bottle of Champagne he had brought. It fizzed warmly, and they both leaned in to lap up the bubbly spill as it ran down the edge of the bottle.

“Just thought you might want to take a look. You’ve been talking about leaving the city so much lately,” Marlon said with a shrug. “A nice getaway, anyway.”

“It’s beautiful. It’s so nice to breathe the fresh air,” Nadine agreed. “So this place is what, a farm?” She was careful not to appear too interested, but she couldn’t help feeling nervous excitement at the sense of possibility. Some quiet voice that she hadn’t heard for years kept suggesting a new beginning. She didn’t examine this prompt too closely; she would inspect it later, when she was away from Marlon and could think properly, without all the noise and hormonal interference his presence created in her.

I would interrupt here, derailing Zelda’s artful dialogue. She could perfectly capture our parents’ voices, a born impersonator. But I liked the history of the wine, and of the ground that it came from.

“I was thinking a vineyard, actually.”

“What, here? In New York?” Nadine arched her eyebrows skeptically.

“I know, I know, it seems weird. But there’s this Ukrainian guy who brought some vinifera grapes over from Europe, and they’ve done very well. Some other guys are trying it now, and I don’t know, I have this feeling that the region could get pretty valuable.” Marlon shrugged, sipping his cup of Champagne. “Just a hunch.”

“A hunch, huh?” Nadine smiled slyly. “I’m not a complete ninny, you know. I figure you’re the kind of guy who likes to financially reinforce his hunches.”

Marlon glanced at her in surprise. He thought he’d managed to conceal his proclivity for putting his money where his mouth was.

“I like risk,” he said lightly. “And I’m about to take another.” He drew a deep breath. “The real reason I wanted to bring you here. I’ve been thinking.” He paused to stare at Nadine. “I want to marry you. I want to run away with you and give you babies and spend the rest of our lives naked and drunk.” Without breaking eye contact, he unbuttoned the first three buttons of her shirt, then stopped, his hand poised at the open collar, near her throat. Nadine’s face registered only stillness. She waited long enough that Marlon began to wonder if he hadn’t drastically overplayed his hand. But finally, she covered his hand with her palm and slid both inside her shirt.

“Fine. But we’ll talk about those babies later.”

Needless to say, whatever conversations they later had about those babies, nothing stuck. I’ve never known if Zelda and I were accidents; at least we both knew that whatever our status, desirable or planned, we were on equal footing. Either we were both wanted or neither was. Perhaps Nadine had unconsciously hoped for kids and grown careless with her contraceptives. Or maybe Marlon had worked his insidious magic until she relented. Our father said we were wanted, “beginning to end, A to Z,” always with a playful grin. Nadine had said that it was a moot point.

By the time we were born, the reality of the vineyard’s disappointing prospects was becoming clearer, and our parents were just beginning to swat nastily at each other, like house cats cooped up too long indoors. We often wondered, as I imagine many children do, whether we were the cause of our parents’ eventual rupture. If they had been different people, a better team, things might have gone differently. This was early days for modern Finger Lakes winemaking, and Marlon’s