Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

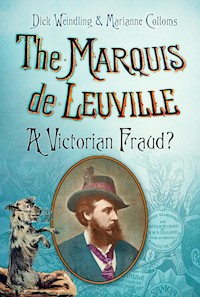

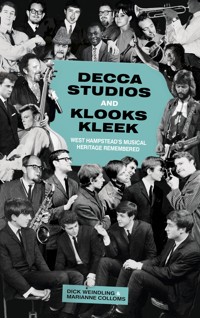

The book explores the history of Decca Studios, where thousands of records were made between 1937 and 1980. Klooks Kleek was run next door from 1961 to 1970 in the Railway Hotel by Dick Jordan and Geoff Williams, who share their memories here. With artists including David Bowie, The Rolling Stones, Tom Jones and The Moody Blues at Decca, and Ronnie Scott, Cream, Fleetwood Mac, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Elton John, Rod Stewart and Stevie Wonder at Klooks, this book records a unique musical heritage. This is the first history of Decca Studios and Klooks Kleek, the famous R&B club. Containing more than fifty photographs, many of which have never before appeared in print, it will delight music lovers everywhere.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 234

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover image credits:

Graham Bond Organisation (Courtesy of Jon Hiseman); Dick Jordan, Harrison Marks and Jackie Salt (Courtesy of Dick Jordan); Django Reinhardt (Courtesy of American Memory at the Library of Congress, William Gottlieb, 1946, LC-GLB23-0730 DLC); Mike Martin Band (Courtesy of Dick Jordan); Mick Jagger (Courtesy of Gonzalo Andrés); Eric Clapton (Courtesy of Matt Gibbons); Zoot and Big Roll Band (Courtesy of Zoot Money); The Beatles with Pete Best (Courtesy of Joe Flannery, from his book Standing in the Wings: The Beatles, Brian Epstein and Me); Dick Heckstall-Smith (Courtesy of Dick Jordan); Tom Jones (Courtesy of Georgio); Geoff Williams (Courtesy of Dick Jordan); David Bowie (Courtesy of Jorge Barrios)

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Decca Studios

2 The Railway Hotel and West Hampstead Town Hall

3 Klooks Kleek

Appendix

Further reading

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dick Jordan and Geoff Williams without whom we could not have written the chapter about Klooks Kleek. Thanks also to Jon Hiseman and Colin Richardson for helping us to contact Dick Jordan.

Other people who have contributed with their memories of Decca and Klooks are:

Denise Barrett

Ric Lee

Neil Slavin

Pat Boland

Patrick Linnane

Paul Soper

Gordon Chamley

Henry Lowther

George Underwood

Roger Dean

Leo Lyons

Derek Varnals

Laurie Fincham

Zoot Money

Mike Vernon

Keef Hartley

Andrew Loog

Chris Welch

Pauline Hurley

Oldham

Mel West

Dave Humphries

Roger Pettet

Adrian Wyatt

Val Simmonds

Every effort has been made to contact the owners of the images reproduced in this book and where known, their name is shown. Illustrations are copyrighted to authors unless otherwise stated.

INTRODUCTION

This is a history of Decca Studios in Broadhurst Gardens West Hampstead, in a building which began life as West Hampstead Town Hall. It is also the story of Klooks Kleek, a jazz and blues club, situated in the Railway Hotel, the pub next door to Decca.

The first chapter looks at the Crystalate Record Company which Decca bought in 1937. They moved into Crystalate’s studio in Broadhurst Gardens which then became Decca’s main recording facility until 1981. Currently the whole building is being used by the English National Opera and their archivist, Clare Colvin, said they acquired it on 27 November 1981.

The second chapter looks at the development of the Railway Hotel and West Hampstead Town Hall, which was built for private functions not as a municipal Town Hall.

The third chapter provides the history of Klooks Kleek, which was a major venue for jazz and the evolving British blues scene. During the ten years from 1961 to 1970, when the club ran, some of the most famous names in jazz and blues played there.

1

DECCA STUDIOS

The Decca Studios building was previously West Hampstead Town Hall, bought by the Crystalate Record Company in 1928. This became Decca Studios in 1937. In its final form, the building housed three studios. Studio One was straight ahead as you entered the building with an upstairs control room, Studio Two was downstairs, and the very large Studio Three, built in the 1960s, was down a long corridor towards the back of the building.

Crystalate

In August 1901 the Crystalate Company was founded at Golden Green (note, not Golders Green), Haddow, near Tunbridge in Kent, by a partnership of a London and an American firm. The British company had begun by introducing colours into minerals and making imitation ivory. The American company produced billiard balls and poker chips, before moving on to making gramophone records from shellac. In July 1901 the American director, George Henry Burt (1863–?), applied for a trademark on the word ‘Crystalate’ to cover all their plastic products. The secret formula to make Crystalate substances was kept in a sealed iron box which required two keys to open it: Burt had one and Percy Warnford-Davis (1856–1919), the English director, had the other. It is said that they made the first records to be pressed in England in 1901/2; but there is no direct evidence of this apart from the 1922 recollections of Charles Davis, the works manager.

The company made records for a large number of the very early labels, such as Zonophone and Berliner. After Burt left Crystalate in 1907 the company was run by the Warnford-Davis family with Darryll Warnford-Davis becoming chairman after the death of his father Percy in 1919. New contracts followed, for example with Imperial Records. Initially imported from America, Crystalate took over their manufacture from 1923 to 1934. Between these dates they produced over 2,100 different titles. In 1926 the company moved their office and recording studio from No. 63 Farrington Road to No. 69, Imperial House. In 1929 they moved again to Nos 60-62 City Road, which they called Crystalate House. A very productive period followed, during which time Crystalate produced large numbers of records for labels including Eclipse and Crown for Woolworths. They also made Victory records from 1928, which were sold in Woolworths for 6d (for more information see ‘The History of the Crystalate Company’ by Frank Andrews, Hillandale News, Vols 134, 135, 136, 1983 and 1984).

The British Pathé website has a short film, Making a Record 1918-1924, which shows how a recording was made and a record pressed.

Rex records were begun in 1933 and made by Crystalate. At first they cost a shilling which represented very good value for enormously popular artists of the day such as Gracie Fields, Larry Adler, Billy Cotton and Sandy Powell. Also on the label were the American stars Bing Crosby, the Mills Brothers, the Boswell Sisters, and Cab Calloway. Between 1933 and their demise in 1948, over 2,200 Rex titles were produced (Beltona by Bill Dean-Myatt, 2007).

Crystalate took over West Hampstead Town Hall in 1928 and moved their recording studio there. That year the Crystalate Manufacturing Company appeared at No. 165 Broadhurst Gardens for the first time in the phone book. A prospectus was published in The Times on 2 February 1928, which announced that, ‘West Hampstead Town Hall has recently been purchased and equipped as a modern recording studio’.

Arthur Haddy (1906-1989) was a brilliant young engineer working with the Western Electric Company. On an audio recording at the British Library, made by him in 1983, he tells how he was engaged to Lilian, the daughter of the popular comic singer Harry Fay (real name Henry Fahey). Born in Liverpool in 1878, Fay started out performing in the music halls and then had a very successful recording career. The Zonophone catalogue for 1913/14 lists over fifty of his records, including the well-known songs ‘Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly?’, ‘Boiled Beef and Carrots’, ‘I Do Like to be Beside the Seaside’, and ‘Let’s All Go Down the Strand’. During the First World War, Harry had a huge hit with ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’.

In 1929, Arthur Haddy accompanied Harry Fay to a recording session at the Crystalate studio in Broadhurst Gardens. Electric recording had just begun and Haddy wasn’t impressed with what he saw there, calling it ‘a load of junk’. He jokingly said, ‘I think I could make a better lot of it on the kitchen table.’ Less than six months later Harry Fay phoned him and said the managing director of Crystalate wanted to see him. Haddy met Darryll Warnford-Davis, who asked him if he’d meant what he said about making better equipment. Haddy explained he’d been joking but was willing to try. In the next few months he made an amplifier and a record-cutting head and took them to the studio for a trial. The Crystalate engineers were very impressed with Haddy’s equipment, which produced better results than anything being imported from America. Warnford-Davis wanted Haddy to join Crystalate and offered him double his present salary, which at first he refused, preferring to stay at the prestigious Western Electric Company. But then, as Haddy laughingly says, ‘My future wife said no bigger salary, no engagement!’ So he moved to Crystalate and brought his new equipment to the Broadhurst Gardens studio. The increase in salary clearly worked and Arthur and Lilian Fahey were married in 1930.

CRYSTALATE ARTISTS

Haddy remembers some of the people he recorded at the Crystalate studio. We are fortunate that many of these early recordings are now available on YouTube.

Jay Whidden

James ‘Jay’ Whidden was born in Livingstone, Montana, about 1890. He was a violinist and band leader who came to England in 1912. He was very fond of recounting his days as a cowboy, saying the frostbitten fingertips on his left hand had been removed by the simple expedient of his cattleman father who amputated them with a knife.

Jay’s family moved to New York, where his father worked in the docks and Jay began to learn the violin after hearing his father play Irish jigs. He became fascinated by Ragtime music, which was very popular in the first decade of the twentieth century. With his friend and co-writer Con Conrad, Jay wrote several Ragtime songs, two of which were put on in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1912. Ragtime spread to England and Con and Jay decided to pool their money and sail by tramp steamer to London. They became the Ragtime Duo and appeared in the show Everybody’s Doing It, which was based on Irving Berlin’s words and music. They made their debut in January 1913 and received very good press notices as ‘real’ American and ‘real’ Ragtime performers.

Based on their success, they brought over an American musical comedy called The Honeymoon Express, complete with special effects of a famous chase between an automobile and train, which was literally done with smoke and mirrors. The show opened at the Oxford Theatre of Varieties on the corner of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road in April 1913. It had a successful run and went on tour. Con returned to America in 1916 and achieved worldwide success with his songs, such as ‘Ma, He’s Makin’ Eyes At Me’.

Jay appeared several times, with another partner, at the London Palladium during the First World War and he continued his song-writing career. In 1925 he was employed as musical director for the Gordon Group Hotels, which included the prestigious Hotel Metropole just off Trafalgar Square – the British Pathé website has a clip of him performing there in 1926. Jay recruited some of the best British musicians for his Midnight Follies dance band and they began regular broadcasts on the BBC in December 1925. This led to great success and Whidden made his first record for Columbia records in March 1926. He went on to sign a contract with Crystalate to appear on its Imperial and Victory labels, and his first recordings were done in August 1928. His 1930 recording of the wonderful ‘Happy Feet’, made in Broadhurst Gardens, can be heard on YouTube. Whidden later recorded for several other companies and his popularity continued on into the Second World War.

Sandy Powell

This very popular comedian was born in Rotherdam in 1900 as Albert Arthur Powell. His father nicknamed him ‘Sandy’ on account of his ginger hair and the name obviously stuck. His radio work during the 1930s made him a household name and his catchphrase ‘Can you hear me, Mother?’ was much parroted. Apparently this expression originated from the fact that his mother was indeed hard of hearing and when, during a show, Sandy dropped his lines, he used the phrase to comic effect while reorganising his script. Once the expression caught on he always introduced his radio shows with the words ‘Can you hear me, Mother?’

In addition to these radio shows Sandy started producing records, several in collaboration with Gracie Fields. His lyrics were based around different trades and occupations, including a dentist, fireman, policeman and several others (some of which can be seen on YouTube). ‘The Lost Policeman’, the first in this series, sold half a million copies. Recorded at the Crystalate studios on the cheap Broadcast label it sold so successfully that Sandy continued to record for Broadcast and Rex and, between 1929 (the date of the ‘The Lost Policeman’ recording) and 1942, he completed a total of eighty-five records.

In addition to his radio work, and in-between producing records, Sandy acted in a number of films and appeared on television and in pantomimes. One of his favoured acts was ventriloquism, during which his animated dummy would often fall apart. In 1975 he was awarded an MBE and he continued to perform up until his death in 1982. There is a DVD of his sketches, entitled, as you might guess, Can You Hear Me Mother?

Charles Penrose, ‘The Laughing Policeman’

Charles Penrose (1873-1952) has been known by a number of names in his time. Born as Frank Penrose Cawse, in Biggleswade, Bedfordshire, his parents decided against the name Frank and re-registered him as Charles Penrose Dunar Cawse not long after his birth. Charles would go on to call himself Charles Jolly at the time of his recording of the much-loved ‘The Laughing Policeman’.

Although his early career saw him follow his father into the jewellery trade, Charles eventually became an entertainer, a theatre performer at the West End and a radio comedian. Charles recorded a number of songs in the ‘Laughing’ series, including ‘The Laughing Lover’, ‘The Laughing Curate’ and ‘The Laughing Major’. He is best known, however, for his amusing song ‘The Laughing Policeman’, which he recorded in the 1920s. This track remained a popular favourite well into the 1970s and was a frequent request on the BBC’s Children’s Favourites.

Master Joe Peterson

Master Joe Peterson signed with Crystalate in 1933 aged 20. But Master Joe was really a woman called Mary O’Rourke, who was born in Helensburgh, Scotland. She was brought up in Glasgow in an Irish show business family, and was the twelfth of fourteen children. With a unique and beautiful voice she won talent contests and was recruited by her uncle to take the place of his boy singers whose voices broke in adolescence. Her uncle, the Cockney entertainer and impresario Ted Stebbings, taught her how to impersonate a boy’s voice in song. She performed in the music halls and had a successful recording career, releasing nearly sixty songs on the Rex label between 1934 and 1942.

Despite her popularity, the BBC refused to let Mary broadcast as Master Joe because they considered her ‘improper’ for dressing as a boy, complete with her trademark Eton collar. She tried to overcome the label of a boy singer and record under her own name but was dissuaded by her uncle. After an unhappy marriage she began to drink heavily. Although her last record was released in 1942 she continued performing throughout the 1950s and even appeared on Scottish television as Master Joe in 1963, aged 50. She died in 1964.

Vera Lynn

Vera Lynn is perhaps best known for being the Forces Sweetheart during the Second World War but she had began her singing career much earlier. She worked with the very popular dance bands of Joe Loss and Charlie Kuntz and made her first solo recordings for Crystalate’s Crown label in 1936. Later, she recorded on their Rex label.

She made an impact on a young Dirk Bogarde. Born in 1921 and brought up near the studios at 173 Goldhurst Terrace, Dirk was sent to Glasgow when he was 13 to live with his aunt and uncle. This was an unhappy three or four years for him, but he found a refuge in Woolworths. He writes in his autobiography, A Postillion Struck by Lightning (1986):

Woolworth’s was my usual haven. Because it was warm and bright, and filled with people. Here was Life … Music played all day. The record counter had a constant supply of melody. To the lingering refrains of ‘When The Poppies Bloom Again’ I would sit on a high stool eating a Chocolate Fudge Ice Cream and beam happily at the world about me. Guiltless. It was all heady stuff.

Vera Lynn recorded ‘When the Poppies Bloom Again’ at Broadhurst Gardens for Crystalate in 1936.

During the Depression many of the record companies ran into financial trouble and were bought up by either EMI or Decca. In March 1937 the record division of Crystalate was sold to Decca for £200,000 (The Times, 2 March 1937). Haddy and his colleague Kenneth ‘Wilkie’ Wilkinson (1912–2004) were worried they’d soon be paid off because Decca had their own studio in Upper Thames Street and didn’t need the Broadhurst Gardens one as well. He remembers that they were recording Master Joe Peterson and the record was a big hit, recalling that they ‘lived on it for nine months’. Then they heard that Mr Lewis (Edward Lewis, the Director of Decca), had decided to close the studio in Thames Street instead and move all the recording to Broadhurst Gardens. Haddy said that they were so enthusiastic that they worked until four o’clock in the morning just for the love of it. Edward Lewis said to Haddy that Warnford-Davis had told him that he got a bargain when he bought Crystalate, but he got an even bigger bargain with ‘young Haddy from Hampstead’ (Arthur Haddy interviewed by Laurence Stapley, Oral History of Recorded Sound, 5 December 1983, British Library: C90/16/01).

DECCA AND SIR EDWARD LEWIS

Origins

The origins of Decca go back to a company called Barnett Samuel and Sons which was established by Barnett Samuel, a naturalised Russian immigrant in 1832. They started out producing tortoiseshell doorknobs, combs and knife handles in Sheffield, but moved to London as the music industry expanded, making and selling banjos. By 1878 they were at No. 32 Worship Street, Finsbury Square. Barnett died in 1882 but the company carried on, led by his son Nelson and a nephew called Max Samuel. In 1901 they were one of the largest musical instrument wholesalers in the country and they had their own piano factory in North London. In 1914 they patented a portable gramophone called the Decca Dulcephone. Many of these machines were used by soldiers in the trenches during the First World War. After the war, sales of the portable gramophone increased and this became the main product manufactured by the company.

The Decca Name

In his 1956 autobiography, Edward Lewis said that nobody knew the origin of the word ‘Decca’. In a 1981 article for the magazine Sounds, Brian Rust, an authority on early records, agreed with Lewis, but noted much later that there was a Sunday radio programme during the 1930s which used a call sign played on tubular bells or a vibraphone; the five notes played being D, E, C, C, A. He also noted that the latest records from Decca were played in the programme. This fits in with the original Decca logo which was a musical stave with the notes D, E, C, C, A, written in crotchets with the letters noted underneath. More recently (in 1988) Edgar Samuel says he was told about the trademark by Wilfred S. Barnett of the original company. In 1914, when Barnett Samuel and Sons produced their portable gramophone, they wanted a word for their exports which could be easily recognised and have the same pronunciation in different languages, so Wilfred Barnett merged the word Mecca with the initial D of their trademark Dulcephone to produce the word Decca.

Expansion of Decca

The story of Decca’s growth and success is really the story of Edward Lewis (1900–1980), a young stockbroker from Derby. In the summer of 1928 Lewis received a telegram while he was on holiday in France, asking if he would be interested in the stock market floatation of Barnett Samuel and Sons. He agreed, and by the end of September 1928 he was the broker of the newly named Decca Gramophone Company. The Samuel family sold out completely. Lewis then suggested the idea of making records to the directors of the new company but they turned it down. So, in January 1929, Lewis decided to form a syndicate called Malden Holdings to buy the ailing Duophone factory at Shannon Corner on the Kingston bypass for £145,000 (equivalent today to about £6.6 million). He also bought out Decca and, when their shares were issued on 28 February 1929, they were oversubscribed twice over. As Lewis said, the success of their portable gramophone meant there was ‘magic in the word Decca’. Lewis became the managing director, but the new company was soon engulfed in the Depression – which began with the Wall Street crash – later that year. Lewis faced a titanic struggle to prevent Decca going under, a struggle that lasted a decade. Within a year of the 1929 share issue, Decca’s bankers were threatening foreclosure, and at its financial nadir some years later, the company even had its telephone cut off.

Despite knowing little about the music business, Lewis was the genius who made Decca one of the largest record companies in the world. The first records appeared in July 1929 and were recorded in the Decca studio at the Chenil Galleries on King’s Road, Chelsea. Early recordings were made with the Billy Cotton and Ambrose dance bands. One of Lewis’s first decisions was to drop the price of records to 1s 6d in 1931, to undercut the other companies. The same year his big coup was to sign the most popular dance bandleader of the time, Jack Hylton. As part of the deal, Hylton asked for, and was given, 40,000 Decca shares; it proved a sound investment for Lewis, as Hylton’s first record for Decca, ‘Rhymes’, sold 300,000 copies. Part of its popularity was the catchy sing-along line, ‘That was a cute little rhyme, Sing us another one do’. In 1932 Lewis bought the British rights for the American label Brunswick at a cost of £15,000 (about £780,000 today). Then in August 1934 Lewis launched US Decca from their offices in New York’s famous Flatiron Building. The key Decca man in New York was Jack Kapp, a Brunswick executive, who brought in the best-selling artists Bing Crosby, Louis Armstrong, the Boswell Sisters, Guy Lombardo and the Mills Brothers.

In 1933, Decca left Chelsea and moved their studios to a former City of London Brewery at No. 89 Upper Thames Street, near St Paul’s Cathedral. But this was not ideal, because the studio was not on the ground floor so when a grand piano was needed it had to be lifted in by crane.

Lewis Acquires Crystalate

In his autobiography, Lewis said that in 1937 Crystalate, ‘had found the going rougher and rougher’. Due to changes in the price of Woolworths, HMV and Columbia records, their financial situation became serious. In March 1937 Lewis bought Crystalate for £200,000 (today worth about £10 million), and through this Decca obtained the budget Rex record label and the studios in Broadhurst Gardens. It was soon decided that the facilities here were better and more convenient than at Upper Thames Street, and so Broadhurst Gardens became Decca Studios.

In May 1937, after two years of discussion, Decca and their rival EMI joint-purchased British Homophone’s masters for £22,500 (about £1 million today). This company, which produced the Sterno label only available through Marks & Spencer, had a factory and office in the Kilburn High Road. The most important artist on the Sterno label was the pianist Charlie Kunz who had sold an astonishing 1 million records. At the time, he was the highest paid pianist in the world, earning £1,000 week. Born in America, Kunz lived in Willesden.

In September 1937 the price of Decca’s 1s 6d records was increased to 2s, but Lewis held the Rex label at 1s 6d. By 1939, Decca and EMI had between them bought up all the other record companies in England, leaving the two companies as rival giants.

An interesting history of the early recording companies in England and America is given in Louis Barfe’s 2004 book, Where Have All the Good Times Gone?The Rise and Fall of the Record Industries.

A search of the Ancestry phone books shows that from at least 1934 Edward Lewis lived at Heath View, Heathbrow, near the Jack Straw’s Castle pub. However, in 1941 his house was destroyed by a parachute landmine, though nobody was injured. He moved to the other side of the Whitestone Pond and lived in a flat, No. 2 Bellmoor, until about 1957. In later life he had a London home at No. 69a Cadogan Place, Chelsea, and his country house was Bridge House Farm in Felsted, Essex. Lewis was knighted in 1951 and died in January 1980, when Decca was taken over by the Dutch company Polygram. Lewis left an estate of £1,104,730.

Technical Advancements

Decca made a number of vital technological developments during the Second World War. In 1943 the company developed Decca Navigation, a form of direction finder, where multiple land-based transmitters broadcast radio signals to aircraft and ships. It became operational in January 1944 and was crucial to the Allies’ success during the D-Day landings. The company was also asked by the government to develop a method of detecting German submarines from their engine noise. At Broadhurst Gardens, Arthur Haddy and the Decca team developed an enhanced low-frequency range detector. This was used by Coastal Command to track submarines and then guide aircraft to depth charge the enemy. After the war the technology was used to produce better sounding, wider frequency range 78rpm records labelled FFRR (Full Frequency Range Recording). Francis Attwood, Decca’s advertising manager, suggested a trademark with the letters FFRR exiting a human ear, and this first appeared in the Gramophone magazine of July 1945. Edward Lewis said the design was of immense value and illustrated the superiority of Decca recording. The FFRR technique led to the noted realism of Decca’s classical recordings. It was then that it was applied to the pop side, with artists such as Mantovani, Charlie Kunz and Ted Heath. The British Pathé website has film showing the Duke of Edinburgh accompanied by Ted Lewis, visiting the Decca Navigator factory in 1957.

The LP

The Long-Playing record was launched in America in 1948 by Columbia Records. The new records were made of unplasticised vinyl (the old discs were made of brittle shellac). It enabled recordings to play for twenty to thirty-five minutes per side at 33rpm, compared with the limited three minutes playing time of existing 78rpm records. Decca was quick to use the LP for their recordings, which first appeared in June 1950. This gave them a considerable advantage over EMI, who stayed with the older format until October 1952. However, both companies continued to issue 78s until February 1960, as so many 78rpm gramophones had been sold. The British Pathé 1957 film of the Royal visit includes a sequence showing an LP being pressed, and ‘old fashioned’ shellac records being destroyed.

Stereo

In 1954, Arthur Haddy, Roy Wallace and Kenneth Wilkinson developed the Decca tree, a stereo microphone recording system for big orchestras. This, and the unusually wide-frequency range used for recording was called FFSS, or Full Frequency Stereophonic Sound. The first Decca stereo recordings were made in May 1954, in Victoria Hall, Geneva. They were the first European record company to use stereo technology, only three months after RCA Victor began recording in stereo in the US. Initially the records were only released in ‘mono’, or single channel sound; the stereo versions were finally issued in the 1960s as part of the ‘Stereo Treasury’ series. Most of their competitors didn’t adopt stereo until 1957.

Ron Simmonds, who played trumpet with the Ted Heath band, talked about the first experimental recordings in stereo before there were twin track stereo recorders:

Turning up at Decca studios I found the whole of the brass section standing out in the street. Bert Ezard told me that the saxes were making their tracks first and we had to wait outside. This was all very new and exciting. However it was being done, it was obviously not being separated on the twin tracks properly, because when we went in to dub our parts, several wrong notes were discovered on the saxophone recording, and we had to go back out into the street while they did the whole thing over again.

(www.jazzprofessional.com)

Decca Recording Artists

Decca had a huge list of artists who recorded thousands of records at the Broadhurst Gardens studio between 1937 and 1981, when the studio closed. It is impossible to cover all of them and only a selection is given here to illustrate the range of music produced. Over the forty-year period the popular music recorded at Decca reflects changing trends.

Classical Music