39,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

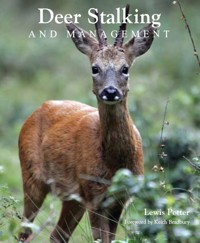

Deer Stalking and Management is a wide-ranging book written in a practical style. It encapsulates the often solitary experiences of the stalker who has only the wildlife for company and considers a world that many people do not know about, do not understand and which many find alien. The author is deeply involved in deer management and stalking and is passionately concerned about the welfare of these beautiful animals. His objective is to both educate and inform. In this book, he summarizes the natural history and characteristics of all the species of deer found in the United Kingdom, assesses the environmental impact of deer, describes the type of damage they do and how it can be identified; explains why deer management is essential, not just for commercial reasons, but also for the welfare of the animals themselves and discusses the organizations associated with deer management and the associated training courses and qualifications that are available. He analyses the rifles and cartridges that can be used by the deer stalker as well as rifle maintenance, ballistics, sights, sound moderators, clothing and ancillary equipment. Careful consideration is given to all aspects of deer management, stalking methods, and taking and placing the shot correctly. He also explains how the carcass should be handled and describes gralloching, skinning and jointing, and deer diseases and injuries and accidents to deer caused by road traffic accidents and wire fencing. With an overview of firearms law in England, Wales and Scotland as it relates to deer, this is a comprehensive guide written in a practical and no-nonsense style. Aimed at all those interested in field sports, country pursuits and especially those interested in deer, deer management and stalking and fully illustrated with 149 colour photographs and 14 diagrams.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 532

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Deer Stalking

AND MANAGEMENT

Lewis Potter

Foreword by Keith Bradbury

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2008 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Lewis Potter 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 787 8

Disclaimer:

The author and the publisher do not accept any responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury, adverse outcome, or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it. If in doubt about any aspect of deer stalking and management readers are advised to seek professional advice.

Illustrations are by the author unless otherwise stated.

Frontispiece photograph by Brian Phipps.

Contents

Foreword

Dedication and Acknowledgements

Preface

1. Deer Species

2. Deer and the Environment

3. Making a Start

4. Rifles and Cartridges

5. Sights, Sound Moderators, Clothing and Ancillary Equipment

6. Managing Deer

7. Stalking Deer

8. The Shot: Before and After

9. Venison, Trophies, Records and Rifle Maintenance

10. Accidents, Injuries and Diseases

11. An Overview of Deer and Firearms Law

Useful Addresses

Further Reading

Glossary

Index

Foreword

I first met Lewis (or Lew, as most friends know him) some twenty years ago when I was working for the Forestry Commission (now Forest Enterprise) as a head ranger. At that time I was dealing with not only wildlife but organizing and running courses in wildlife management for Forestry wildlife staff from all over the UK. I was also assisting with deer stalking courses for the BDS and BASC. I qualified as an assessor and verifier for NVQs and later ran similar courses for Otley Agricultural College.

In 1990, after some years of informal involvement with deer, Lewis came on one of our courses at Cannock Chase to, in his words, ‘see how things are supposed to be done’. This was one of the earlier courses that involved not just classroom work, but a high input of practical assessment and marksmanship. It was not very often we had a student using his own make of rifle.

Lewis has already written two successful books: one on beekeeping, another of his hobbies, and recently one on his full-time job of gunsmithing. With this latest book Lewis has attempted to answer a lot of the novice stalker’s queries concerning calibres, ammunition and other related matters about firearms. Deer, of course, figure largely in the book, with sections covering species, habits, habitat, management and diseases. I was glad to see the section on ticks and Lyme disease, which highlighted what can be a very nasty disease in humans if not treated quickly.

I am glad he has made the point about always and never, as deer rarely do what you expect and often confound us by doing something completely different to how we expect things to be.

Please enjoy the book and glean everything you can from it: there is a lot of really useful information in these pages. Take note and always strive to be the best stalker and shot – the deer deserve only the best. Enjoy your time in the forest and on the hill, taking great care to be safe in all you do.

Keith (Brad) BradburyChief Ranger (retired)Chilterns, West England Conservancyand Thetford Forest

Dedication

This book is dedicated to my wife, Sue, who translates my scribble into legible English and tolerates my prolonged absences when I am out with the deer.

Acknowledgements

I thank The Crowood Press for the opportunity to write a book on a subject close to my heart and which has fascinated me for years. Special thanks go to those who generously contributed their time to read parts or all of the manuscript and offered ideas and advice. These include Keith (Brad) Bradbury, who also kindly provided the Foreword, Stuart Burlinson, Patrick Faulkner, Paul Harding, Lawrence Langridge, John Noble and George Wallace.

For help with photographs and various aspects of photography I owe thanks to G. ‘Harry’ Alderslade, Steve Carter, Keith Bradbury, Tom Braithwaite, Chris Fresson, Paul Harding, Chris Hardy, Mark Howard, Thom Jarman, Kevin Mace and Calvin Crossman (butchers), Roger Nurden, Brian Phipps (wildlife photographer), Nick Ridley (professional photographer), Pierre Shone, and David Stretton (Donington Deer Management).

None of this would have been possible without the help and permission of those landowners whose properties I have been privileged to roam. These include John Child, Gerry Barnett, Mr R. J. Berkeley, Frank and Carol Forbes, Dr Lennox Gregorowski, Mr Michael Fitzgerald, Annette Gorton, Lord and Lady Farnham, Lawrence and Yvonne Langridge, Mr and Mrs John Long, Mr Dennis Winnett and the Greensleeves Shooting Club. I also acknowledge the help and assistance I received from the BASC Deer Department, The Deer Initiative, Brenda Mayle and Dr Robin Gill of Forest Research, Jack Pyke of England, Swarovski UK Ltd and the Tree Council.

Some things are not possible without extra help, so for acting in the male model role I thank Will Teiser and my sons Matt, Dan and Jamie, and also my daughter Lucie for her computer skills.

One person who deserves special thanks is my good friend Adrian Howard who, right from the start, unhesitatingly gave many hours of his own time to help whenever possible, and also his wife Janet, who provided free meals with her usual cheerfulness. I thank you all, and anyone else who might have helped, even in the smallest way, but especially with that vital ingredient: encouragement.

Preface

There is one thing you can be sure of when discussing deer and their habits and behaviour, and that is the words always and never should only be used with considerable caution. Their use may give an authoritative ring to any statement but will rarely be a reflection of all the facts, as nature seldom deals in absolutes.

It is, of course, true that deer have instinctive reactions to certain situations that tend to follow a pattern and each species has behavioural habits sometimes very different to other deer. Even those species with strong herd instincts will, however have individual animals capable of doing the unexpected.

The more one goes out stalking, or just deer watching, the more one realizes that there is so much to learn. No two days are ever quite the same. If one stalked for a lifetime there would always be something new to be learnt. If the words always and never do have a use it is perhaps in the context ‘things may never always be the same’.

LASP2008

Chapter 1

Deer Species

We are most fortunate in the British Isles to have a large and flourishing population of deer living wild and often remarkably close to human habitation. Nowhere else in Europe is there such a variety of deer. In the UK there are six species roaming freely: the truly native red and roe, and the introduced fallow, Japanese sika, muntjac and Chinese water deer. In addition, in parks there are the larger Formosan sika and the Manchurian (of which there may be a few Formosan living a feral existence) and the Père David deer. Apart from these there is the red/sika hybrid, which is causing considerable concern in some parts of the country as it is in danger of spoiling the true red deer bloodlines. Even reindeer or caribou have been introduced in the north of Scotland, but do not qualify as quarry animals in the UK; they are unusual as the only species where the females carry antlers.

Of the introduced deer, fallow have been with us long enough to be naturalized. They were certainly brought here shortly after the Norman Conquest and were kept in deer parks – a privilege usually granted by the King. Many of these parks are documented, even those that have ceased to exist, so we can be fairly certain of an original date of introduction around the eleventh to twelfth century. Surprisingly, some of those early parks, even those with wooden paling fencing, survived until the Second World War. There can be little doubt that there were escapees over the intervening centuries, and aiding their establishment were the harsh punishments meted out to commoners who broke the forest laws and dared to take the ‘King’s deer’. Areas designated for the sport of kings and noblemen must also have been an aid to the fallow’s successful colonization.

The spread of sika, muntjac and Chinese water deer, although of much later origin, is a well-documented story of escapees becoming established. Apart from those that escaped, their establishment in some parts of the country is no accident: there have, for example, been isolated pockets of muntjac so far removed from other populations that they can only have got there with human assistance.

By whatever means they arrived, most stalkers, deer watchers and photographers would regard our small island as being all the richer for having them. They are beautiful, shy and fascinating creatures – a valuable asset to our great variety of fauna. When uncontrolled, however, they can be a considerable nuisance, not only damaging to crops and gardens but to our native habitat. This in turn, as well as the loss of ancient established flora, can have a detrimental effect on other wildlife.

The deer that the amateur or recreational stalker is most likely to encounter are fallow, roe and muntjac. Red deer are usually regarded as a very valuable asset, but management opportunities sometimes become available in a park environment. Sika, at the time of writing, have a limited range and Chinese water deer (CWD) are constricted very much by their preferred habitat. In those areas where CWD occur they seem to be doing exceptionally well and something of a credit to the principles of deer management in this country. Yet if within the following pages there is perceived to be a bias towards fallow, roe and muntjac, it is for the very good reason that not only are they the deer most commonly encountered by the average stalker, but in general they are, due to their increasing numbers and wide distribution, the most cause for concern and therefore need proper management.

SPECIES AND PRIMARY CHARACTERISTICS

Red Deer (cervus elaphus)

Average lifespan: 14–18 years (dependent upon habitat and feed)

Adult male: stag

Adult female: hind

Young: calf.

Established: Circa twelve million years (in its present recognizable form), cervus elaphus scoticus being regarded as a subspecies of cervus elaphus, which occupy the continental land mass.

Size: The largest UK land mammal with a variation in size dependent very much upon habitat; animals in the Scottish highlands are smaller than their lowland cousins. A hill stag may, on the hoof (live weight), be around 250lb (115kg) and 40–44 inches (1–1.12m) at the shoulder. A really big southern woodland stag can exceed 400lb (180kg) and stand around 50in (1.27m) at the shoulder. Hinds are smaller depending upon the environment, averaging 200lb (90kg) weight and around 42in (1.07m) at the shoulder. General appearance is of handsome muscular animals. In areas of very poor feed, weights of stags have been recorded at less than 200lb. Thetford Forest stags are usually the largest, with some at well over 500lb (225kg).

Colour and coat: A coarse coat, fairly uniform in colour with only subtle differences. In summer the coat is generally regarded as chestnut brown, although some of a lighter hue have even been described as foxy red. In very bright light some do appear redder than others, but it is perhaps more the darker winter coat colouring of a fox that is being alluded to rather than the summer coat so similar to a roe. Although rare, white animals are not unknown. A dark dorsal stripe runs from the back of the head to the tail. This stripe is a very dark brown, appearing almost black in some instances. Underneath, from the chest, along the belly and between the back legs, they are lighter in colour. The caudal patch or rump hair, which can vary from a brownish yellow or ginger when in winter coat to off-white in summer, is a very prominent raised feature when a deer is alarmed. In the first full winter coat they appear less red, the coat being longer and fluffier. Coming up to shedding the winter coat it turns quite distinctly grey, falling out unevenly to give a ‘moth-eaten’ appearance common to most species of deer in this condition.

Other features: Greyish-brown muzzle, 6– 8in (12–15cm) tail (colour as body hair), fairly large prominent ears (much more noticeable on the hinds), with grey fur inside.

Antler development: The antlers are formed from main beams carrying tines or ‘points’. The classic development is the ‘royal’, a twelve-pointer that on each beam carries three forward tines, which, counting upwards from the coronet, are brow, bey and trey. At the top of each beam is a cup-shape of three upwards-pointing tines or points. A head that carries more points is an ‘imperial’. On the open hill there are plenty of lesser animals, in terms of antler development, that never achieve anything very dramatic, let alone reach ‘royal’ status. In rich, milder lowland climates it is not so unusual to find antlers with eighteen or twenty points and some of park descent with even more.

Antler growth with red deer gives an indication of age, but really only under ideal conditions of feed and habitat:

Calf: no antlers or pedicles.

Knobber (yearling): the start of pedicles noticeable as bumps on the head covered by normal hair.

Spiker: two plain curved spikes – the first antlers.

Staggie: spiker with the addition of brow tines and maybe two points at the end of the beams.

Stag: continuing development of tines, length and weight until around twelve years old, after which there is normally a decline in quality.

As an indication of ageing antler formation on its own is not completely reliable. Poor feed or genetics can result in less than perfect development. One example is what is called a ‘switch’, an older animal but with antler development similar to but longer than that of a spiker. A mature stag in, say, the hard conditions in the Western Highlands might only carry antlers heavier than but similar in configuration to a staggie. This may well be his full genetic complement or, with an older animal, could be due to declining quality, the condition known as ‘going back’.

One real peculiarity is the ‘hummel’, a stag without antlers or even rudimentary pedicles. Not using food and energy growing antlers, they are usually large bodied and, reputedly, capable of holding a harem during the rut.

Habitat and distribution: Red deer, in spite of their size, are remarkably adaptable and, while historically they are woodland animals, have adapted well to open moorland, and in small, isolated pockets even in mixed farmland. Primarily grazing animals, they are also great opportunists and will browse trees and shrubs, depending upon whether their normal food is in short supply, while buds and young leaf growth offer a succulent alternative. In the winter the deer’s metabolism slows down so they need less intake of food and rely more on bodily reserves built up in the summer and autumn. Even so, when the weather is really hard they can be driven to attempting to break into fenced crops, chewing off the smaller branches of young trees and even bark stripping.

The greatest concentration of red deer is in Scotland, while in England, as well as various isolated pockets, there are colonies in Cumbria, the New Forest, Thetford Forest, Exmoor and Dartmoor. This species is slowly increasing in numbers and the total population estimate for 2006 covering Scotland, England and Wales was 362,420. The estimated expansion of the red deer population is believed to be approximately 6 to 7 per cent per annum, allowing for natural deaths, accidents, planned management and poaching.

Magnificent red stag in the autumn mist. Note thick neck, mane and a caudal (rump) patch, visible even from the side. (Brian Phipps)

Red hinds in winter coat – good-looking, muscular deer.

Distribution of red deer, 2000. (Reproduced by kind permission of the Tree Council) Dark green: distribution in the 1960s Light green: distribution in 2000

Sika Deer (cervus nippon)

Average life span: 16 years

Adult male: stag

Adult female: hind

Young: calf

Established: Sika were first introduced to the UK around 1860 as additions to collections and deer parks. As always, there were escapees. The most well-documented instance was the establishment of a herd on Brownsea Island, some of whom swam to the mainland about 1900.

Size: Sika stand just a little taller than fallow, but the stags in particular are of more substantial build. An average sika stag will stand about 36–38in (91–97cm) at the shoulder, a hind around 34in (86cm). While the average live weight of a hind hovers around 100lb (45.5kg), a stag can top 165lb (75kg).

Colour and coat: A sika hind in summer coat under dappled shade can be mistaken for a fallow. The glossy chestnut coat with white spots is where the confusion can arise, but whereas a fallow with spotted coat also sports a lateral line above the belly, with the sika it is a series of distinct spots. The sika also has obviously hairless inner ears. The summer coat of the stags is a match for the hinds, sometimes a little darker chestnut. In winter both sexes grow a very dense, long coat – the hinds being grey, the stags dark grey or black.

In summer they still have a distinctive white, heart-shaped caudal patch outlined with black, a grey/white underside and a black dorsal stripe. In winter the caudal patch is more of an off-white. These rump hairs can be erected as an alarm signal large enough to look out of proportion to the animal.

Other features: The most distinctive feature of the sika of either sex is a white or whitish line in ‘V’ or ‘U’ form above the eyes. This gives a scowling appearance and, in the case of a mature stag, can make it look especially threatening. Another feature that is a useful aid to identification is prominent white metatarsal glands on the outside of the rear legs, while close up a unique mark like a black thumb print can be seen in the ears.

Antler development: There are a number of similarities between sika and red deer, including the ability to interbreed. Antler development is also similar, starting as a knobber, then spiker (very occasionally forked), the second set almost certainly forked and, by the third set of antlers, usually at least four or six points. After this they will normally carry eight points.

Habitat and distribution: Sika have the potential to become very widespread. Primarily grazers, they quite readily browse and, while they have their preferences for certain grasses and herbs, appear to adapt to a varied diet more easily than other deer. With their secretive lifestyle, it all enhances their chance of continuing to spread.

The main population is in the west of the Scottish highlands and along the borderlands. In England the main populations are in the southwest, but they also occur in significant numbers in Lancashire and are gradually spreading in the northwest. The estimated annual expansion is 1½–2 per cent, the 2006 survey indicating around 12,000 animals.

Sika stag in winter coat. Of special interest are the colouration of the face, which gives the impression of ‘frowning’, the heart-shaped caudal patch and light marking on the hocks where the metatarsal glands are located. (Brian Phipps)

Sika hinds in summer coat. Recognition differences between these and fallow are the ‘frown’, lack of lateral line along the body, shorter tail and hairless inner ears with ‘thumbprint’. (David Stretton)

Distribution of sika deer, 2000. (Reproduced by kind permission of the Tree Council) Dark green: distribution in the 1960s Light green: distribution in 2000

Menil fallow buck in summer coat, regarded by many people as the most handsome of deer. Note lateral line below white spots, long tail and, being a menil animal, brown stripe down tail and around caudal patch, rather than the black found with the common variety.

Fallow Deer (dama dama)

Average lifespan: 12 years

Adult male: buck

Adult female: doe

Young: fawn

Establishment: Fallow have been with us for around 900 years (see above) and their distribution is linked very much to the location of the early deer parks. Although technically a nonnative species, it is one of the most recognizable types of deer, even to non-stalkers.

Size: An adult buck will stand nearly 36in (91cm) at the shoulder, although this would qualify as a very good animal. Does are usually 3–4in (7–10cm) smaller, but occasionally one comes across unusually large does. The average weight of a buck on the hoof is around 110lb (50kg), but bucks of up to 140lb (64kg) are not that unusual; does average 90lb (41kg).

Colour and coat: There is a greater variety of colour in fallow than in any other of our deer, from white to chestnut, light brown and black and shades in between, spotted and unspotted (sometimes with ghost spots). The common has a dark chestnut summer coat with white spots. The menil (sometimes called the Mediterranean type) are very light brown, even with an orangey hue, and are very spotted: in the opinion of many stalkers and deer watchers, they are the most handsome of fallow. There are black fallow with a lighter underbelly and allblack animals that are a true melanistic variant. White fallow do look a little odd, but it is surprising how a white animal can live in an area for years and yet only occasionally be seen.

The winter coat is darker, even the white variant looking a little greyer, while the common type becomes almost a dark chocolate colour, the spots hidden by the winter coat. True menil animals still show spots even in winter coat.

A rare and very localized variant is the longhaired fallow from around the Ludlow area in Shropshire. They have the colouring of the common variety but long hair, not just on the body but including head and neck.

Other features: Fallow have the longest tail of all our deer with (except in the pure white and black types) a dark stripe down the middle. They are very active in its use; many a fallow has given away its position by flicking the tail from side to side when pestered by flies. The caudal patch is white with, in most variants, a black borderline. The spots along the flank above the belly merge into a continuous line, which is one of the visual aids that distinguish them from sika.

Antler development: Both the peculiarity and great attraction of the fallow buck is that elegant formation, the palmated antler. In a mature animal with a good ‘head’ there are brow and bey tines, wide palms (hence the term palmation), small points along the back edge of the palms called spellers and a rearwards tine below the palm. Early development starts with single spikes in the first year; the next year is a longer spike (which then qualifies as a beam) that can show some flattening on the end and small brow tines. Development after that should, by the next year, be two tines each side with clear signs of developing palmation. Antlers that develop forked ends rarely form really sound palms.

Development of the male in the old verderer’s language is as follows:

Buck fawn: first year

Pricket (carrying spikes): second year

Sorel (beams and brow tines): third year

Sore: fourth year

Bare buck: fifth year

Buck: sixth year

Master buck: six years and older

Habitat and distribution: Fallow browse and graze, have a fondness for deciduous woodland, especially if it is not too dense, will make use of orchards and are quite happy to raid arable farmland. Heath and open moorland are not at all to their liking.

Fallow are fairly widespread in the east, Midlands, south and southwest of England, with pockets scattered up through Scotland. Estimates of the total population are around 200,000 animals, with an annual increase of 3½–4 per cent per annum.

Fallow doe still in winter coat, which is starting to look rather shabby.

Fallow occur in a greater variety of colours than any other of our deer.

Distribution of fallow deer, 2000. (Reproduced by kind permission of the Tree Council) Dark green: distribution in the 1960s Light green: distribution in 2000

A mature roe buck. The antlers are still rather pale, having recently lost their velvet, while the winter coat is starting to look patchy along the back just above the haunches. The white spots under the nostrils emphasize the ‘Mexican moustache’ appearance at the nose. (Brian Phipps)

Roe Deer (capreolus capreolus)

Average lifespan: 10 years

Adult male: buck

Adult female: doe

Young: kid

Establishment: Roe are one of the two truly native species (red being the other) and archaeological remains confirm their existence here since around 400,000 BC. In Norman times, when deer parks thrived and great protection was given to red and fallow, roe held a lower classification as ‘beasts of the warren’ and were hunted extensively for food until, in the southern parts of the UK, they became almost unknown and were possibly wiped out in some areas. Having at one time almost lost them, interest was gradually rekindled and the twentieth century reforestation programmes aided their recovery.

Size: About the size of a goat and with similar characteristics of outline and movement. An adult buck will stand some 24–26in (61–66cm) at the shoulder and a good specimen will exceed 50lb (22kg) live weight. A doe is only a little shorter, averaging 24in (61cm) but of lighter build; 40lb (18kg) is not unusual.

Colour and coat: In summer the coat of both sexes is a bright foxy red, giving the animal a very clean appearance. Black roe are occasionally found in some parts of the country and there are very rare reported sightings of white roe, although it is not unknown for some of those to turn out to be a small fallow, a goat or even a lost sheep in ‘deer territory’. Sightings of skewbald roe have been reported. Many roe have a whitish patch on the chest, known as a gorget patch, but this is a feature that seems to vary from area to area.

The winter coat is very long, pulls out easily and appears in various hues of light grey. In some parts of the country they can be found with a distinctive black ‘cape’ running from the back of the neck and across the shoulders. There have been several witnessed sightings of a buck whose winter coat was a light creamy colour but appeared to have a quite normal red summer coat. Observing roe squeezing under electric fencing leads one to conclude the hair does not conduct electricity.

Other features: The face of the roe is distinctive and quite unlike any of our other deer. Roe have a black nose and muzzle, with a white patch under the chin that continues around to the top lips to appear as two white spots under the nostrils. The black of the muzzle runs from the nostrils to the corner of the mouth, giving what is often referred to as the ‘Mexican moustache’ look. They have large ears, quite hairy on the inside and outlined around the edge in black.

At the rear end the caudal patch differs between males and females. This serves as a useful guide to identification between bucks and does when culling in the winter. White or just off-white, from a distance it appears whiter in the winter but this may be due to the profusion of winter hair and the contrast with the darker grey winter coat. The male patch is a kidney shape that grows down from just above the anus. The doe’s is larger with an anal tush that hangs down like a tail. Although generally regarded as not having a tail, there is a very short spinal end around an inch long that only becomes really obvious when skinning an animal.

Antler development: Roe antlers can vary a lot even in the same location, and more so if they have been left unmanaged. Unlike our other deer, roe grow new antlers in the winter, the hardest time of year for feed, and the availability or otherwise of food with a good nutritional value can make a lot of difference to the next year’s antler formation. Given the effects of feeding, genetics and accidents, roe are capable of producing some weird and wonderful antler formations.

What most stalkers would regard as the classic adult formation is the ‘six pointer’, which has two basic forms, either a lyre shape or a narrower, somewhat straighter but heavier formation of the main beams, sometimes referred to as the southern type. The main beams ideally carry heavy pearling, a brow tine and back tine or point. Sometimes the back point is very long and gives the impression of forked beams; at other times it may be quite insignificant on an otherwise larger set of antlers.

The ultimate collector’s ‘treasure’ is a perruque head, which is a spongy mass of uncontrolled antler growth due to insufficient testosterone. Unfortunately, preserving such a spongy mass as a specimen can be almost impossible. A similar situation occurs with old antlered does, where sometimes not all of the growth is hard or it is in the form of a skullcap like a small perruque head.

Antler growth with roe is rapid and a male kid can have small knobs on his head before Christmas: in stalker’s parlance this is a ‘button buck’. Given exceptionally good winter feed small conical antlers may even develop. A yearling may carry single bifurcated spikes appearing as a small ‘four pointer’. Normally by the next year the buck may achieve a modest sixpointer status, but there is no guarantee. Socalled ‘murder bucks’ have only a pair of spikes, while some deer may carry four, five or seven pointers, or develop completely strange formations, sometimes resembling pieces of rotten hazel, that defy accurate description. With roe, estimation of age based simply on antler size is one of the most unreliable methods.

Habitat and distribution: Roe are primarily browsers and will wander along nibbling here and there apparently aimlessly. If they do find something of special interest they will browse quite heavily, but seem disinclined to stay in one place for too long. In the winter they will spend a lot of time grazing and this is when reasonably large concentrations of roe can be seen together.

They are very successful colonizers and need only modest cover. While a wood with undergrowth of hazel interspersed with small open patches of grass or bluebells is roe heaven, an overgrown field headland backed by a good thick hedge can provide them with all they need. Very territorial, they will quite often stay around the same area for years if undisturbed, assuming there is sufficient food. A doe in Thetford Forest fitted with an identification collar at twelve months old was killed in a road accident within 200 yards of where she was originally collared. Not only that, but she was calculated to be fourteen years old and was pregnant!

The population estimation for 2006 was 1,603,456 with an annual increase of 4½–5 per cent.

Roe deer grazing during February. A ‘family group’ with mature buck in velvet on the left, doe and buck kid on the right. The doe is immediately recognizable from this angle by the anal tush.

Distribution of roe deer, 2000. (Reproduced by kind permission of the Tree Council) Dark green: distribution in the 1960s Light green: distribution in 2000

Muntjac (muntiacus reevesi)

Average lifespan: 12 years

Adult male: buck

Adult female: doe

Young: fawn

Establishment: There are several species of muntjac, but the one established in the UK is the Reeves muntjac. The original colony was introduced as a park animal around 1900 and both escapees and deliberate releases have helped its spread. Its ability to escape should come as no surprise to anyone used to its ability to find its way into fenced woodland.

While regarded in some areas as a considerable pest and far more destructive than could have been originally envisaged, they are interesting animals, perhaps the oldest of the deer species, dating back in excess of thirty million years.

Size: As always, while there are exceptions and unusually large bucks may sometimes be encountered, an average shoulder height is around 18in (46cm). An adult doe is little different in size and shape, perhaps as little as one inch shorter with a smaller head. From a distance, and without binoculars, it can at first be difficult to distinguish between male or female if the antlers are cast or not very prominent. Weights will vary from around 36lb to 40lb (16–18kg) for a buck and 34lb to 36lb (15–16kg) for a doe.

Colour and coat: Both summer and winter coat are a similar reddish brown, the summer coat being a somewhat more glossy red. They can appear grey, or certainly of a greyish tint, when the winter coat dies prior to falling out. This is not such a dramatic change as with some deer, as both summer and winter coat are comparatively short. The coat is lighter underneath running from the chest to a white rump patch.

Other features: The tail, the most distinctive part and that which novice stalkers usually see, is red on the top and white underneath, carrying some of the longest hairs on the body. When alarmed or running away the tail is held erect like a warning flag.

The males of this ancient species are also recognizable from their elongated pedicles, the black hairline running in a vee shape from nose to forehead, and the prominent canine tusks. The black line on females normally joins up across the head at the top of the vee. The ears are internally virtually hairless, both sexes have large suborbital glands, and any muntjac is identifiable in profile by its rather pig-like appearance. The males also have long and visible upper canine teeth.

Antler development: Muntjac can be born at any time of year and the first antler growth is relative to age rather than the season of the year. Regardless of that, the bucks eventually settle into the same annual cycle, casting in April/May. The pedicles start to grow around six months of age and antlers around eight to ten months, usually as a simple extension of the pedicles, that is, without coronets.

Later antlers are single tines, often with hooked ends and, in ‘better’ heads, a small brow tine. Ageing by antler size once the buck has reached adulthood is only a rough guide, but generally older bucks carry antlers with heavier bases to the tines and correspondingly sturdy pedicles.

Habitat and distribution: Muntjac are great opportunists and, although coniferous leaves do not seem to be attractive to them, almost any greenery within reach will suffer. Bluebells, cowslips and dog’s mercury disappearing in ancient woodland are a sure sign of the presence of muntjac.

Any dense undergrowth serves as cover and they can even be found in urban gardens, parks and similar areas, sometimes even on overgrown brownfield sites. Next to the roe they are probably the most adaptable of deer and equally at home in dense forestry or next to a housing estate. The 2006 population estimate stood at 149,100, with an estimated annual increase of 14–15 per cent. With such a secretive and diminutive animal it begs the question: will we ever really be sure of reasonable accuracy of numbers?

Young muntjac buck. Note the ‘little piggy’ profile, so unlike any other of our deer. (Brian Phipps)

Muntjac doe. Note the virtually hairless inner ears. Even at this angle the facial stripes are visible.

Distribution of muntjac deer, 2000. (Reproduced by kind permission of the Tree Council) Dark green: distribution in the 1960s Light green: distribution in 2000

Mature muntjac buck. This shows the typical hooked antlers with small brow tines, prominent suborbital glands and large upper canine teeth. (Brian Phipps)

Chinese Water Deer (hydropotes inermis)

Average lifespan: 6 years

Adult male: buck

Adult female: doe

Young: fawn

Established: Chinese water deer (CWD) were another Victorian import brought in originally as novel additions to zoos and parks. It is recorded that escapees were established in the countryside surrounding some of the still-captive populations before the Second World War. Although of limited distribution and a non-native species, it is very important as it is believed the UK now holds up to a quarter of the world’s population of this increasingly rare animal.

Size: Similar to a muntjac in size but with a slightly more leggy appearance and the hindquarters held higher than the shoulders. Average shoulder height for a buck is around 19in (50cm), a doe around an inch (2.5cm) less. Weight is also very much on a par with muntjac: 30–40lb (17–18kg) for a buck and only 2–3lb (1–1.5kg) less for a doe.

Colour and coat: There are subtle variations in colour, varying from reddish brown to a lighter sandy colour in summer coat, with lighter colouring under the chest and belly. In winter coat the same variations appear, but of a darker hue. There is no caudal patch.

Other features: The most talked-about and distinctive feature is the appearance of the face when viewed head on. The dark nose and eyes, which, while of an almond shape, appear like round black buttons face on, and the round and obviously hairy ears all contribute to the well-known ‘teddy bear’ appearance.

The other notable feature is the canine teeth, short in the females but of quite dramatic length in males – around 2½in (6.5cm) long for an adult buck. The tail is around 3in (7½cm) in length and the same colour as the main body hair.

Antler development: Chinese water deer do not carry antlers.

Habitat and distribution: Chinese water deer are more restricted in their choice of habitat and less adaptable than other deer. As the name suggests, their normal habitat is water meadows, reed beds and grassland river areas. The tops of some root crops suffer damage and commercial daffodil fields seem to be a favoured haunt.

They are not considered a particularly sporting quarry, having a tendency when alarmed to simply run off a little way before couching down in cover. Their limited distribution, small numbers and little effect on the environment mean most stalkers are unlikely to see one. As the main content of this book is the management of deer in relationship to the environment, CWD have little part to play.

Distribution: Limited areas of eastern England where suitable habitat occurs, including Bedfordshire and parts of East Anglia.

Estimated numbers: Depending upon which authority one consults, this appears to vary from 10 to 25 per cent of the world population, with figures as low as 650 animals (1994) to around 2,000, including park animals, by 2004.

Chinese water deer. The ‘teddy bear’ look is accentuated by the rounded hairy ears. From this angle the eyes appear as round as buttons. (Brian Phipps)

Chinese water deer starting to lose its winter coat, hence the moth-eaten appearance. The back legs being longer than the front give it the strange high stance on the rear quarters. (Brian Phipps)

Fallow buck having cast its antlers. The top of the pedicle looks quite raw and attractive to flies.

Antlers: The Annual Cycle

The growth and casting of antlers demonstrated by the five antlered species in this volume follow the same biological principles. Antler is bone and so it is a considerable strain on the male’s metabolism to produce the large formations displayed by mature red, sika and fallow, which, in the simplest of terms, may be thought of as almost equivalent to growing another foreleg.

The time of casting (losing the antlers) is due to declining levels of testosterone. This leads to decalcification in bone cells below the coronet causing a line of weakness so that the antlers fall off, usually one shortly followed by the other. When this first happens the exposed top of the pedicle may exhibit bleeding, which, for a short time until it heals, is rather attractive to flies.

New growth starts almost straight away, is soft, easily damaged and covered in a thin layer of tissue and blood vessels referred to as velvet, owing to its appearance. The males at this time are very aware of their vulnerability and, since older males with large antlers cast first, younger animals will take advantage to exert a little authority while they have the chance. A dispute between males in velvet among herd deer takes the form of standing on their back legs, ears down and head held well back while ‘boxing’ with their front feet. If you are lucky enough to be reasonably close to mature red stags when they do this, it is impressive how tall they stand, but the overall effect is more comical than macho – a sort of ‘handbags at dawn’ scenario rather than a real duel. Sometimes they forget themselves and will make a head thrust at another deer, but usually pull up short before making actual contact. At this time of year hinds will also box, perhaps inspired by the stags, but it seems exceptionally rare for fallow does to indulge in such antics.

As time moves on towards the rut – or, in the case of muntjac, simply as part of an annual cycle – the testosterone levels rise, causing hardening of the antlers and inhibiting further growth. The blood flow to the velvet ceases, it dries and splits away, becoming a surface of great attraction to flies that cause considerable annoyance to the deer. The dried strips of velvet will eventually drop off, but this process is normally assisted by the deer rubbing the antlers against convenient small trees or bushes in a manner that can sometimes prove very destructive. When first losing the velvet antlers are quite pale, but the fraying of undergrowth soon adds a dark contrast to the more ivory-coloured tips. The male is then truly in hard antler (sometimes referred to as ‘hard horn’). The time of year when the males cast their antlers may vary by several weeks, depending on size and the individuals, but generally falls into the following periods:

Red: March onwards

Sika: March onwards

Fallow: late March onwards

Roe: November onwards

Muntjac: April/May

Handbags at dawn. Red stags boxing while in velvet, antlers still growing.

Velvet drying out on the antlers is very attractive to flies.

Communication

Deer communicate in various ways: vocally, by body language and territory marking. Most noticeable, even to people with little interest in deer, is the vocal enthusiasm of males in the rut. Red stags roar at this time of year, sika give a rather strange whistling shriek, fallow a ‘belching’ groan, roe bark (but this is no different to the normal challenge). The female muntjac, to attract a mate, can emit a bark that seems more of a scream (a little like a vixen) and bucks have been heard to give out an almost musical warbling and clicking sound when in the vicinity of a doe in oestrus.

Males and females use a warning bark or, in the case of sika, a sharp whistling squeak. Muntjac will, when alarmed, retreat into cover and bark with the insistency of a terrier, often for several minutes at a time. The females of all the species have their personalized call recognized by the young. In their turn, the young have their high-pitched bleat, an almost birdlike squeak when very young, that is recognized by the mother.

Body language encompasses the ritualized parading in the rut where males will strut like clockwork toys to impress, quite often walking parallel to each other. This can be followed by a more direct challenge in the form of a real or mock charge, then a pushing/wrestling match with antlers locked. Muntjac appear to be less formal when they fight using antlers, hooves and slashing with their large canine teeth. All of the deer will stamp a forefoot when alarmed but perhaps not always sure of the danger.

Rolling of the eyes and flattening of the ears are signs of aggression and red deer are fairly pugnacious at all times within the herd environment. Viewed from the purely human perspective, it is a bit like a bad attack of bullying in the school playground. There is a constant push for domination and only the strong make it to the top. Mature red hinds will hold their position by shoulder barging, biting and kicking out with a foreleg. Other hinds, stags in velvet and even spikers in hard antler are soon dealt with quite ruthlessly by an old hind, while with fallow it is most unusual for the does to challenge all but the youngest animals, and then very much by just pushing them out of the way.

The other form of communication is territory marking by depositing scent either from frontal scent glands, the suborbital glands or interdigital glands (between the hooves) and laying down urine. Sika stags score the bark of trees as territory marking while that most territorial of deer, the roe bucks, fray small trees and bushes and make small scrapes. Muntjac will also aid marking their territories by depositing faeces (pellets, or fewmets) in the same spot, eventually producing small heaps.

Sika stag marking territory. (Brian Phipps)

The Rut

Muntjac

When we refer to the rut we normally mean the mating season. This is not applicable to muntjac, which breed at any time of year. The other species respond to annual cycles that, with the exception of Chinese water deer, are interrelated with the hormonal changes that also produce antlers.

A female muntjac in oestrus will call to attract a mate, unless a male is already in attendance, but may well finish up with several bucks responding. This can then involve some rather intricate footwork with deer dodging in and around trees and bushes, each male trying to get the female for himself. When fully receptive the doe will sometimes stand, tail erect and cocking it from side to side a little like a metronome. The victorious buck will continue to guard her, showing the whites of his eyes and adopting an aggressive stance if any lesser buck is still within sight. Usually mating takes place in thick cover and normally a single fawn is born seven months later, whereupon the doe can mate again within a couple of days.

Chinese Water Deer

CWD rut mainly in December and have multiple births: up to four is not uncommon and seven has been recorded, the majority being born around June. Mortality of the young seems particularly high: an estimated 40 per cent of the fawns die in the first few weeks, many from predation.

Roe

Roe rut in July or August, the degree of activity being governed to a certain extent by the weather. Sultry, thundery weather seems to stimulate the bucks’ urges: I have an outstanding memory of a large buck stamping back and forth on a grassy bank, antlers laden with undergrowth, while in the background lightning sizzled against a blackening sky. Sometimes the peak of rutting may be earlier or later, and considerable differences can occur between locations only a few miles apart. Occasionally what is termed a false rut takes place later after the real rutting activity has died down. There are also rare instances, witnessed in one or two areas of the Cotswolds, where the rut continued from late July into September without a break, although perhaps at a more even pace than the frenzied activity sometimes seen. What also makes this unusual is that the ‘calm after the storm’, which normally results in a very quiet period as the deer rest and regain their strength after the rut, does not happen. Deer life continues much as normal with the same animals out and about as earlier in the year.

Both roe bucks and does have their own territories and the chasing that takes place between the sexes is the female leading the buck on. They may run in circles around a tree producing the fairy-like roe-rings. A doe may let a buck chase her before discarding him and choosing another buck to mate with, or she may mate more than once. Bucks competing for females will fight quite furiously without so much of the ritual posturing adopted by the larger deer. It is not unusual to see the loser chased across a couple of fields. Bucks that have been injured by a superior male are not that uncommon and even does – presumably when unwilling to mate – can be roughly handled by a buck when the testosterone levels are high.

A peculiarity of roe deer is the delayed implantation, which means the fertilized egg is kept in the ovaries until December when it moves to the womb. With a gestation period of five months it means most young will be born in May or June rather than the middle of winter, which would otherwise be the case if delayed implantation did not occur. Roe quite commonly have two kids, especially, it would seem, when there is good feed and little pressure for territory. On occasions they may give birth to triplets, and four foetuses have been recorded. This also means that, unless by chance the doe previously mated with the same buck, the buck in attendance with the doe and young is not the sire, although we refer to them as a family group. There is also some indication that the ratio of male to female births may be governed by population density – fewer females when numbers are high, and vice versa.

Muntjac buck marking territory. (Brian Phipps)

On the lookout. Roe doe in foxy red summer coat. (Brian Phipps)

Fallow

With herd deer there are subtle differences regarding the male’s approach to mating, the one common factor being the two sexes normally living in separate herds for most of the year. Fallow have rutting stands that can vary from a simple scrape to established stands that are used continuously for years by successive bucks. Approaching the rut, which starts in October, the buck’s Adam’s apple becomes noticeably more pronounced, the tassel of hairs (that visible sign of sex, even with a young animal) appears more obvious and the animal produces a musk that is a most unpleasant smell. The neck thickens and the suborbital glands secrete a milky fluid. To enhance even further his desirability to the females, the buck will urinate in the rutting stand and wallow.

The buck calls in the females by the distinctive groaning. Receptive does will normally be mated at the rutting stand. In a park environment, where there may be an unusually high number of males, it is not unknown for a desperate buck to forsake a rutting stand and even pin a doe against a fence or wall in an attempt to mate. In the wild any other male that comes near an occupied rutting stand will be threatened – this is where the parallel walking often comes in, with tails erect and much stamping of forefeet. If that is not sufficient to see off the intruder, they will lock antlers, wrestling and pushing until the animal that gives up breaks away. The winner rarely pursues him very far, since holding the rutting stand is a far more important consideration.

As with roe and in common with the other herd deer, the weather has an effect. With the autumn ruts, however, it is crisp, frosty weather that seems to be conducive to rutting activity: a few unseasonably warm days and the rutting activity may flag even to the extent of bucks temporarily leaving their stand. Some years the rut is very vocal, while at other times it is almost as if they are not around. Sometimes a lone buck may be heard groaning a month or two into the new year without obvious reason, although it may be due to a doe that has come late into season.

The gestation period for fallow is just over seven and a half months (theoretically 230 days), usually a single fawn being born, or very occasionally twins.

Fallow buck on his rutting stand. (Brian Phipps)

Red stags fighting during the rut – one of nature’s great spectacles. (Brian Phipps)

Sika

Sika stags, in common with the other male herd deer, take great efforts in the rut to make themselves attractive to the hinds. They wallow, adding their urine to the wallow, and rip up vegetation that they carry on their antlers. If really successful, this may be draped like a mane across their shoulders.

Sika in the rut have a slightly less formal arrangement than fallow or red. The rut may occur at any time between September and November. The stags will adopt a territory and attempt to round up and defend a harem, or just wander around in an opportunistic manner seeking receptive females.

After six and a half months (gestation period 195 days) a single calf is born, the peak period for calving falling in June. There is no known record of twins.

Fallow fawn. A typical place to find young deer is a nettle bed. When lying still it is amazing how well the camouflage works, although it looks quite bright in the open.

Red

To watch two really big red stags fighting during the rut is one of the most impressive sights in nature. The sheer size and power of these animals, antlers clashing together, turf torn from under the hooves, accompanied by grunting and snorting, is a demonstration of brute strength. The rut normally starts in late September or early October when the stags leave their all-male summer herds to find the hinds. In the Highlands this splitting up and migration of the stag herds is referred to as ‘breaking out’.

The neck muscles of mature stags (usually five years old and onwards, but can be younger in a very favourable environment) become noticeably enlarged; this is made more obvious by a thick mane. The suborbital glands also become enlarged, giving the eyes a slightly oriental appearance. Wallowing, spraying urine under throat and neck, and ripping up vegetation and sometimes discarded rubbish to carry and emphasize the antlers all add to the sex appeal.

Each stag attempts to round up and hold a harem or ‘parcel’ of hinds and tries to keep them to himself in a ‘holding’ area that is fairly loosely defined. Effectively the largest, most powerful animals have first choice. Such is the competition that it can become an impossible job. While busy defending the hinds against another stag, others can come in literally behind his back and take females out of the herd. It is a very trying time for a red stag, during when he rarely, if ever, has a chance to rest, sleep or feed. When finally exhausted, which in various parts of the country is termed ‘run’ or ‘spent’, younger or lesser stags will take their chance.

The peak calving month for red deer is June after a gestation period of about 235 days. Normally there is a single calf, twins being rare.

Young Deer

The young of all deer are born camouflaged in the form of spots or stripes, which blend very well with most forms of natural cover. This striking pattern fades and has disappeared by the time of their first winter coat. Initially left in cover, the hind or doe is normally in fairly close attendance unless there is a perceived threat, when it will often attempt to lead the intruder away from the young. This, and the mother’s attempts to keep the area where the young is deposited clean of ‘deer-related matter’, is all done for protection. As the young gains strength it will eventually follow the mother and, as it grows, even cavort around like a spring lamb.

As listed above, the young do not all have the same description: red and sika young are calves, while the young (and this is only up to twelve months old) of fallow, muntjac and CWD are fawns. Although it is not uncommon to hear roe young referred to as fawns, they are in fact kids, a term used for many centuries. In the sixteenth century a male roe was a kid for its first year, a girle for the second and a hemuse for the third, before simply becoming a buck. Goats are the other remarkably similar animal, at least in size and general outline, they have kids (at one time goatlings), and this crossover of names was once even more obvious as male goats were gatbucca (goat buck).

So, if a deer that has calves is, when pregnant, in-calf and when birthing it is calving, should a roe be in-kid (as with a goat) and kidding when giving birth? The answer, if one wishes to stick with a direct descent from the old English, would appear to be yes. Also, having given birth, the doe would have kidded. Through the wonderful complexity and subtlety of the English language, however, it seems that ‘to fawn’ or ‘fawning’, the act of bringing forth young, may be used in a broader sense than for just those animals that produce fawns. It appears, therefore, that a roe kid can be fawned, but I feel there is a lot to be said for kidding.

Chapter 2

Deer and the Environment

Deer are ruminants and, like all such prey animals, are equipped to gather food comparatively quickly then retire to a safe location to ruminate or ‘chew the cud’. This involves regurgitating some of the recently gathered food (a portion referred to as a bolus) and chewing it at leisure. This is only possible because, like cattle, the stomach or rumen (hence ruminants) is divided into four parts.

The main section receives the fresh bulk material. After chewing the cud this, when re-swallowed, is diverted into the recticulum and then the omasum (second and third compartments), where microorganisms and bacteria start their work. The final stage is the now partdigested food moving into the abomasums to complete the four-part stomach cycle prior to passing into the intestines.

Deer’s intake of water is not very high and when they do drink it is a rather inefficient operation. As they raise their heads they can be seen to dribble much of it. They get moisture from the plants they eat, rainwater on leaves, and dew on grass as part of their intake. At one time it was generally believed that roe virtually never drank, but on rare occasions during extended periods of hot weather they will drink, even standing in streams to accomplish it.

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

Environmental impact is broadly the effect deer have on their surroundings. This includes damage to commercial crops and the natural environment, the number of deer killed on the roads and even intrusion into semi-suburban areas. Too many deer leads to increasing damage; in hard weather limited feed can mean starvation and, as numbers increase, a greater possibility of disease.